Bounty

|

Bligh and the loyal sailors leave the bounty

|

||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

The Bounty was a three-master of the British Admiralty , who in 1787 led by Lieutenant William Bligh to a trip to the South Seas departed to cuttings of breadfruit from Tahiti to the Antilles to bring. On the planned return trip, the famous mutiny took place in 1789 , which has since been the subject of novels, non-fiction books, films, plays and radio plays.

prehistory

Because of the American War of Independence , the earlier regular and inexpensive grain deliveries from the North American colonies of Great Britain to the Caribbean were canceled. After that, there were several famines there, which killed around 15,000 people between 1780 and 1787. In particular, the owners of the large sugar cane plantations in Jamaica therefore demanded a constantly available and inexpensive basic food for their slaves .

Joseph Banks , president of the Royal Society , the Royal Society for the promotion of scientific research, recommended for this purpose by the sweet potato similar tasting, vitamin-rich breadfruit . Once planted, the trees would get by with almost no care and could be harvested all year round. Banks was enthusiastic about the previously little-known fruit on James Cook's first circumnavigation.

Instead of procuring and transferring the cuttings themselves, the large landowners obtained the financing of the project from the crown, with the support of banks: On May 5, 1787, King George III. a corresponding order to the Admiralty. This tried to fulfill its first commercial order, which served neither military nor research purposes, at the lowest possible cost.

The ship

Origin and name

Due to time constraints and because storage space was more important than firepower for non-military journeys, the Admiralty acquired the civilian coal transporter Bethia . James Cook had also used similar ships for his South Seas voyages, but they were much larger. The Bethia had a hull length of 27.7 m, a maximum width of 7.3 m and a capacity of 215 tons (for comparison: Cook's Endeavor had 368 tons).

The narrowness of the ship turned out to be problematic later, as it was overcrowded with a crew of over 40 men. This caused conflicts over and over again. In addition, due to the cramped conditions, it was not possible to station marine infantry on the ship, which could possibly have ensured the discipline as armed ship police.

The ship was moved to the Admiralty Shipyard in Deptford Yard near Chatham in late May 1787 . There it was converted into a “sailing greenhouse” and the masts were shortened. On June 8, the new acquisition and the new name Bounty were announced publicly.

The name means “good deed, kindness, gracious gift” and was intended to express the “ grace ” of the king to provide cheap food for the starving slaves of his subjects in the West Indies with the help of the breadfruit expedition.

HMS or HMAV?

On-board weapons of the Bounty were four four-pounder cannons and ten small rotating guns - enough for the purpose of the trip, but to this day the cause of confusion about the exact designation of the vehicle: Whether it was "HMS, His Majesty's Ship" or "HMAV, His Majesty's Armed Vessel ”, often still seems controversial. The latter designation, HMAV, goes back to the small size, armament and manning: What was called "His Majesty's Ship, HMS" at the time, was divided into six classes, from rank 1 , ship of the line with at least one hundred cannons and around 850 Crew up to rank 6 (mostly frigates ) with 20 to 28 six-pounder cannons and a good 150 crew. The sloops with 10 to 18 cannons and a crew of 60 to 120 men ranked lower than ships, as were even smaller armed schooners , brigs and war cutters .

The following clearly speaks in favor of the original name HMAV:

- The original side elevation of the Bounty is labeled "Bounty armed Transport ...".

- Lieutenant Bligh was only promoted after his return to captain - often referred to as post captain because of the ambiguity of the word . The latter rank roughly corresponds to the future sea captain . At that time, the Admiralty would normally have provided a post captain with at least one 6th rank ship .

- Bligh himself lamented the loss of literally "His Majesty's Armed Vessel" in letters he wrote to Banks and Duncan Campbell in Batavia after his rescue.

The Bounty started its journey as "HMAV, His Majesty's armed vehicle". It was not until the spectacular trial preoccupied the nation that a "ship" was stolen from His Majesty; after that there was a kind of official language regulation: "HMS Bounty ". The descendants of the mutineers, on the other hand, still use the name “Armed Vessel”, as did the British Privy Council in its ruling of October 30, 2006.

The nautical equipment of the ship was quite good: the on-board clock was the K2 built by Larcum Kendall . It is certain that the commandant also had the report on the island of Pitcairn , which was discovered in 1767 and already wanted to visit Cook.

The crew

The crew of the Bounty included a total of 46 people. The command was 33-year-old Lieutenant William Bligh , who had already served as a helmsman ( Sailing Master ) on James Cook's third voyage. He had also got to know Tahiti and the local conditions. Without the consent of the local rulers, it would hardly have been possible to remove and root a large number of cuttings. Bligh was also appointed at the instigation of his mentor Joseph Banks and his wife's uncle, Duncan Campbell . The large landowner in Jamaica and shipowner also owned Bethia . Campbell had suggested the expedition to the king, and Banks had given all his support to the petition, which was his own proposal. So Bligh was obliged to both, and each of them put protégés on his ship. For example, Bligh hired five midshipmen instead of the required two.

The highest ranking after Bligh was the helmsman ( sailing master ) John Fryer . Fryer's appointment by the Admiralty had placed him in the rank of Acting Lieutenant for the duration of the trip - he performed a position that would otherwise have been a lieutenant. He also commanded the First Guard.

At the beginning of the trip there was by the commander five officer functions of officer representatives ( Warrant Officers ) and their assistants ( Mates ; Mate = mate, mate) have been completed: the helmsman John Fryer and his two assistants ( Master's Mates ) Fletcher Christian and William Elphinstone, Gunner and Second Watchman William Peckover, Boatswain William Cole, Carpenter William Purcell, and Surgeon Thomas Huggan. Officer-like status had the Champion ( Gunsmith ), the on-board recorder ( Captain's Clerk ), the captain servant ( Captain's Steward ), the assistant of the doctor and the two had come for the expedition aboard botanist.

In the officer rank were six men: two helmsman ( Quartermaster ) and a helmsman Mate ( Quartermaster's Mate ), an artillery master assistant ( Gunner's Mate ), the sailmaker ( Sailmakers ) and the assistant of the Carpenter ( Carpenter's Mate ).

Five midshipmen ( midshipmen ) were also more (formal) or less (technically) over the sailors under which the Hannoversche Cooper Henry Hill Brant on chien. A half-blind Irish violinist named Michael Byrn was listed as ordinary seaman. Bligh wanted to ensure a good mood and healthy movement, but this was not particularly well received within the crew: They did not want to dance “on command” and would have preferred to have one more fully qualified seaman on the weakly manned ship. After the mutiny, Byrn was the first in the dinghy and was promptly pushed out by his "comrades". In addition to him, seven others, most of whom were listed as sailors, were exempt from guard duty because of their functions, for example the cooper, the cook, the butcher, the sailmaker and the two botanists.

So Bligh had 45 men, but not two dozen real sailors. In Spithead , where the Bounty had arrived at the end of September to make final arrangements and await the final order to travel, there had already been fourteen desertions , but the crew members who were missing as a result could largely be replaced. Bligh knew the future mutineer Christian from several trips together, first on the Cambridge in 1782 and later for Campbell. Christian had asked the lieutenant by letter to order the bounty . Bligh had also been with several other members of his crew before, with the veteran artilleryman Peckover under Cook, for example.

The outward journey

The shortest route via Cape Horn to Tahiti was ordered . From there, the Bounty should head for the Torres Strait with its cargo , possibly pick up more plants on Java , reach the Antilles via the Cape of Good Hope , deliver the plants and return to England. Any unknown coastline or islands should be mapped , as far as the schedule allowed - a general order valid for every ship of the Admiralty.

On December 23, 1787, the Bounty finally set sail . It was the second attempt after the order received in December - the first had to be canceled after a few days due to heavy weather. In Santa Cruz de Tenerife bunkerte Bligh water and provisions. With his departure on January 10 or 11, Bligh introduced an advanced three-watch system there for the benefit of his crew and appointed Christian as the third watchman.

On February 7, 1788, the ship passed the equator .

On March 23, the Bounty set course for Cape Horn. Despite the minimal likelihood of being able to circumnavigate the cape with the small ship at this time of year, Bligh tried to carry out the order despite the heavy raging storm. There were minor injuries and illnesses in the team, and people grumbled about food. Bligh was accused of having a cheese seared for himself from the crew's provisions.

The fact that Bligh Fryer loudly criticized in front of the crew because he had not shortened the sails in time, i.e. endangered the ship, should increase the tensions between the two highest ranking on board considerably in the future.

It was not until April 22nd that Bligh decided to change course to the Cape of Good Hope, which the Admiralty had granted him as a stopgap measure.

The Bounty arrived on May 24th in False Bay near Cape Town, where it had to be overhauled. Christian, who had hardly any cash with him (a stopover was not planned), had to borrow money from Bligh in order to be able to perform properly on land during the layover, which Bligh would later accuse him publicly several times. The ship left again at the end of June.

There was a fortnight stopover from August 20th in Adventure Bay ( Bruni Island , southeast of Tasmania ). Then, on September 19, Bligh discovered the Bounty Islands , a group of tiny rocks at 47 ° 45 ′ S , 179 ° 3 ′ E (southeast of New Zealand ). The ship was now near the date line .

On October 9, the able seaman James Valentine died of blood poisoning , which Bligh put down to unclean instruments of the board doctor. On the same day there was another uproar with Fryer, who had refused to sign the log and only did so when Bligh ordered him to do so in front of the assembled crew.

Tahiti

The Bounty reached Tahiti on October 25, 1788 and anchored in Matavai Bay .

The ship spent five months there because the breadfruit tree was in a dormant phase at the time of arrival and cuttings could not be taken immediately.

The team and Bligh enjoyed life with the friendly people, there were numerous contacts with Tahitians. Some crew members, such as Fletcher Christian and Peter Heywood , entered into long-term relationships. Some, like Heywood, got tattooed , as was the local custom.

On December 9, 1788, the ship's doctor, who had since been relieved of his duties, succumbed to drunkenness.

At the end of December, the discipline seemed to have deteriorated. On January 5, 1789, three men tried to desert with a dinghy; However, they were caught again on the 22nd and punished with one or two dozen lashes with the " nine-tailed cat ", which was considered extremely mild in view of the crime at the time: even the death penalty by hanging would have been an option for desertion and theft of the dinghy.

On April 4, 1789, the Bounty left Tahiti and headed for the Endeavor Strait , the southernmost part of the strait between Australia and New Guinea . She had 1015 young plants on board; it must have been correspondingly tight on board (picture).

mutiny

On April 24, 1789, Bligh made a stopover in Nomuka ( Tonga Islands ) to supplement food and water like Tasman 1643 and Cook 1777. One of the residents, an older man, remembered him. An argument soon broke out. Locals stole equipment from the Bounty, for which Bligh blamed his third guard, Christian. Then he tried to hold some of the tribal leaders hostage in order to get the stolen property back, but was finally convinced that this would be of no use and released the hostages again.

To the southwest of Tofua , today also part of Tonga, the mutiny broke out on April 28th :

The previous evening Christian had been accused by Bligh of snatching coconuts from the ship's supply. Christian, who felt that he had been treated unfairly again, then got drunk and told some sailors that he wanted to return to Tahiti on a raft. They then seem to have persuaded him to sit out Bligh instead.

Christian's four-hour watch began at 4 a.m. after he hadn't slept half an hour (he had stayed on deck until 3:30 a.m. on his off watch). From 4:30 a.m. onwards there were debates on deck, around 5:20 a.m. Bligh was arrested and handcuffed. Christian, Mills, Churchill, Burkett and Adams threatened him with guns. Heated debates arose, Bligh raged, Fryer shouted at Christian and the small dinghy was prepared for watering. At 7 am that was done, but the boat was in such bad shape that one Bligh launch conceded.

After half an hour this was watered. To Christian's surprise, 18 men wanted to get on board. By eight o'clock the launch was full, but Bligh was still aboard the Bounty . In the dinghy there were two small barrels of water (maximum 125 liters), some wine, rum, bread and rusks (around 75 kg in total) and some coconuts. A little clothing was thrown into the boat, the carpenter was allowed to take his tools with him and the clerk was able to gather all of Bligh's most important documents. Shortly after eight o'clock he was the last to be forced into the boat and new debates began when he tried to change Christian's mind one last time. At the same time, the men in the launch asked for and received about 10 kg of jerky meat. Shortly before 10 am, was loosened as the nachgeschleppte last two hours the boat, they threw them four cutlasses , but no firearms. The handover of the timer K2 ("Bounty Timekeeper") was denied to Bligh.

The hard core of the mutineers consisted of nine people: Edward "Ned" Young (the driving force - he had instigated Christian) and Christian, furthermore Adams, Brown, Martin, McCoy, Mills, Quintal and Williams. There were also nine active followers. Around 22 were relatively loyal, some undecided. Some had stayed on the bounty voluntarily , others had been forced to because there was no more space on board the dinghy. Martin had been dragged back from the dinghy after an argument with Peckover. Later, 16 men decided to stay in Tahiti and wait for the inevitable search expedition instead of accompanying Christian.

The ride of the launch to Kupang

Together with Bligh, Fryer, Peckover, and 16 other men were in the seven-meter-long and two-meter-wide dinghy, which plunged almost eight inches deeper than the intended maximum mark.

Equipped only with Compass , Log , a octants and his pocket navigated the dinghy Bligh of Bounty in 41 sailing days more than 5,800 kilometers to the Dutch trading post Kupang on Timor , the only European candidate base. Little did Bligh know that in 1788 a much closer base had been established in Port Jackson , the port of present-day Sydney.

The only fatality on the way was John Norton, who had been slain by locals on Tofua, the island that came to supply immediately after the mutiny. As is clear enough today from Bligh's report (compare, for example, Forster 1791), the fight arose because Bligh and his people had nothing useful to exchange for the food they needed, and they also had no firearms to obtain the food by force. The tofuers had offered their wares and felt they had been stolen when the group left for no consideration. So they attacked and paddled after the fleeing British until Bligh had some clothing thrown into the water.

Bligh immediately and drastically rationed the remaining food to 60 grams of rusks and 125 milliliters of water per person and day, measured in an improvised coconut shell scale with a musket ball as a weight.

On May 24th, when checking the provisions, it turned out that the rations had to be cut again.

Until Kupang discovered and recorded about 40 small islands. After his experiences on tofua, he hardly dared to land anymore. It was not until May 29, 1789 that he ventured to an island he called Restoration Island (after restore , 'to recover'). There was a little game and drinking water to be found there. On the following days he drove through the Torres Strait and named several of the Torres Strait Islands after the days of the week of the first week of June (Tuesday, June 2 to Friday, June 6, 1789).

On June 14, 1789, 48 days after the mutiny, the launch reached Kupang. The successful voyage of the overloaded boat was, also in circles of its critics, as a maritime masterpiece by Bligh. At times the swell was so strong that the sails in the trough of the waves could no longer hold the wind, at times there were lulls in which the malnourished crew had to row. The men waited in Kupang for the first opportunity to return home, but continued to suffer from the hardships they had barely survived and from the tropical climate. Two died in Kupang.

Bligh took the first opportunity to return. He left Kupang on August 20, 1789, had to wait again in Batavia for the onward journey and reached Portsmouth on March 14, 1790 together with his servant John Samuel and the cook John Smith. Ten more people arrived on later ships, including Fryer and Peckover; three of them, including Fryer, had been temporarily chained by Bligh's order. Two of Bligh's men had died of a fever in Batavia and the surgeon Thomas Ledward made his last voyage aboard a Dutch frigate that went down in a storm. Twelve of the 18 exposed with Bligh survived. In October 1790, Bligh was acquitted in the court martial that always had to take place when a ship was lost.

The odyssey of the Bounty and its end

Between Tubuai and Tahiti

The mutineers first drove to Tubuai , where they anchored for a week, discussed and decided to settle. They therefore sailed back to Tahiti first, met their wives again and equipped themselves to found a colony on Tubuai. They lied to the local rulers that they had fulfilled the breadfruit mission and then met Captain Cook, who had instructed them to found a colony and asked his friends in Tahiti to take care of the bounty accordingly.

In Tubuai, the ship was allowed to dry out on the beach and a fort began to be built, but the project had to be abandoned after three months as a failure due to disputes among each other and fights with the locals. The withdrawing group, which two Tubuaians had joined, left 66 dead, including six women. There were only two injured among the Europeans.

On September 22nd, 1789 - Bligh had already left Kupang for England - Christian arrived again in Tahiti. Since the mutineers had to expect to be found there, Christian was determined to leave as soon as possible. However, 16 of his comrades decided to stay. Christian secretly set sail again with the eight remaining Polynesians and a small group of Polynesians; there is even talk of kidnapping. One of the 16 remaining in Tahiti jumped overboard while the sails were being set so as not to have to go along.

The small crowd around Christian sailed through the Cook Islands , Tonga and Fiji in search of a place to stay , before turning east. Some of the women had since left the group, so that in addition to the nine British men there were only four men from Tahiti, two men from Tubuai and twelve women from Tahiti on board.

On January 15, 1790, the island of Pitcairn was sighted, which no European had set foot before. Pitcairn was located in the middle of the Pacific, far from any trade route, which was desirable for the mutineers around Christian. At that time, your position was marked with an error of around 180 nautical miles (approx. 330 km) on the Admiralty's nautical charts , which corresponds to at least a day's voyage. If it was habitable, the island was the ideal hiding place.

The end of the bounty : Stranded in front of Pitcairn

It was decided to put the bounty on the ground to facilitate the landing of the belongings, yams and sweet potatoes as well as some pigs, goats and chickens.

One of the mutineers set fire to the wreck on January 23, 1790 in order to destroy any trace visible from the sea. At the same time, it was impossible for any of them to return to an area where they would be picked up by the Admiralty: it was clear that in such a case each of them would have died by hanging. Remnants of the bounty are still a few meters below the ground and in the immediate vicinity of "Bounty Bay", the landing site.

The story of the mutineers ended with their settlement of Pitcairn and the death of John Adams there (1829). Fletcher Christian had probably died violently on Pitcairn as early as 1793. 49 people, mostly direct descendants of the mutineers, still live there today. Every year on January 23rd, Bounty Day , they drag a model ship out onto the water and set it on fire.

Arrest and punishment of the mutineers

Pandora's expedition

After the mutiny became known, the Admiralty decided to arrest the mutineers and bring them to court. The search was entrusted to Captain Edward Edwards, who set off in early November with the frigate Pandora and a crew of 160. He landed in Tahiti on March 23, 1791, 18 months after the mutineers arrived. Edwards had all 14 Europeans still alive put in chains and locked in a 3.4 by 5.5 meter structure on the aft deck, which became known as Pandora's Box (" Pandora's Box ").

At the time, two Europeans were already dead: Matthew Thompson had shot and killed Charles Churchill in 1789 or 1790 and had succumbed to blood revenge by his Tahitian family.

On the way back, the Pandora ran into a coral reef off the coast of Australia on August 29, 1791 and sank. The chained prisoners Stewart, Hillbrant, Skinner and Sumner drowned alongside 31 men of the crew. The 99 survivors covered about 1100 miles in dinghies - again to Kupang.

Court martial

In September 1792, all of the English brought back by Edwards were charged. Four were acquitted:

"The Court further agreed That the Charges had not been proved against the said Charles Norman, Joseph Coleman, Thomas McIntosh and Michael Byrn, and did adjudge them and each of them to be acquitted."

The remaining six were sentenced to death by hanging ; However, Peter Heywood , William Muspratt and James Morrison were pardoned by the king on October 22nd. Burkitt, Ellison and Millward were hanged on October 29, 1792 on a yard of the warship HMS Brunswick in Portsmouth harbor and "hung for two hours" according to the verdict.

After the trial

Only four of the mutineers were still alive at the end of October 1793, namely Young, Adams, McCoy and Quintal, from the end of 1800 only John Adams, who died on March 5, 1829, the third from the bottom of the team.

William Bligh was commissioned to undertake a second breadfruit voyage, this time on a suitable ship and escorted by the Assistance . He brought the plants to St. Vincent on January 24, 1793 and to Jamaica on February 5 . In 1801 he took part next to Nelson in the naval battle of Copenhagen , was especially praised for his bravery and in 1805 was appointed governor of New South Wales . He was once on trial because of his tone with a subordinate officer and witnessed two further mutinies, each time he was rehabilitated and finally promoted to vice admiral. From 1810, however, he was no longer in command. He died in December 1817.

John Fryer remained in the fleet service as a master. In 1805 he was sailing master of the William (12), a supply ship on the Gibraltar station. He was later promoted to master of a ship of the line of the first rank before leaving the Navy in 1812. He died in England in 1817, six months before Bligh.

Thomas Hayward and John Hallte traveled with the punitive expedition of the Pandora and, after the shipwreck, drove down Torresstrasse again in an open boat. Both were later killed at sea.

Peter Heywood was allowed to stay in the Navy after the pardon and also made it to the captaincy. The first dictionary of the Tahitian language emerged from his Tahitian notes . He died in 1831.

The carpenter William Purcell died as the last survivor of the Bounty on March 10, 1834 at Haslar Hospital, Portsmouth. His death room is said to have had a view of Spithead, where the Bounty had set sail 47 years earlier.

The wreck of the Bounty today

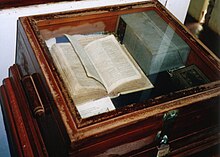

The people of Pitcairn have preserved some relics of the Bounty mutineers that are still on Pitcairn, such as the Ship's Bible in Adamstown Church . In 1933 the residents of Pitcairn found the wooden oar of the Bounty , it is now in the Fiji Museum in Suva , the capital of Fiji (Pitcairn was administered by the British Governor in Fiji until 1970). The pivot and hinge of the bounty's rudder are located in the Otago Museum in Dunedin , New Zealand. They are a present from Pitcairner Parkin Christian.

In 1957 the underwater photographer Luis Marden carried out a diving expedition to Pitcairn on behalf of the National Geographic Society . Together with Tom Christian, a descendant of Fletcher Christian, he managed to find the remains of the burned-out wreck. The keel of the ship could still be made out, and they also found fittings, a cannon, cannon balls and the anchor. The cannon and anchor are now up and on display in front of the parish hall on Adamstown's central square.

In October 1998, a group of underwater archaeologists from Australia's James Cook University visited the wreck again. The divers found several fittings and another cannon, which was also raised.

The wreck is still in Bounty Bay off Pitcairn near the landing site ("The Landing") in three to five meters water depth. The place is in the surf area , so that a dive - which may only be carried out with the permission of the island council - is not without danger. The wooden remains of the ship are no longer recognizable, but the large pebbles from the ballast , which are clearly different in shape, structure and color from the surroundings, are clearly visible over an area of around 8 × 15 meters (as of March 2000).

Replicas

- Bounty (ship, 1960) , 1st replica, sunk in 2012 in Hurricane Sandy

- Bounty (ship, 1978) , 2nd replica

For the film adaptation from 1935 Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer bought the schooner Lily and had it converted into a bounty .

The Mutiny on the Bounty in Literature and Film

Contemporary descriptions

Between 1790 and 1817, Bligh wrote a number of descriptions of varying depth, all of which were very popular. His articles were published in German as early as 1791, translated and edited by Georg Forster .

Bligh served as personal records

- his private logbook. Since the ship's log had to be returned after the voyage, he had also made private records. The original is in the State Library of New South Wales , Sydney .

- the notebook written in the dinghy, in which Bligh describes the course of the journey, his arrangements, the rationing of food and the 40 islands he discovered. It is kept in the National Library of Australia , Canberra .

The official documents are:

- The ship's log , recorded by the Captain J. Samuel, is in The National Archives , London (formerly the Public Records Office ).

- The court records.

The other side put other representations on paper:

- Edward Christian, Fletcher's brother, professor of law at Cambridge, wrote a Short Reply to Captain Bligh , portraying him as an intolerably strict officer.

- Peter Heywood, sentenced to death and pardoned not least thanks to his influential family, defended his behavior in a similar way.

- James Morrison, also pardoned, likewise.

- John Fryer, who had had a heated argument with Bligh on the open boat trip, also published his less flattering memories for Bligh.

Bligh's fame as one of the most skilled seafarers and navigators of his day faded in his lifetime.

Novels and short stories

- John Boyne: The cabin boy. (Original title: Mutiny on the Bounty ), 2009.

- Max Engemann: Storm over the island , St. Benno-Verlag GmbH, Leipzig 1988, ISBN 3-7462-0295-7 (life story of the bounty mutineer John Adams).

- Robert Merle : The Island. Novel . Aufbau-Taschenbuch, Berlin 2002, ISBN 3-7466-1221-7 (novel based on the mutiny).

- Charles Nordhoff and James Norman Hall: The Bounty Trilogy : Mutiny on the Bounty , Men Against the Sea and Pitcairn's Island . Little, Brown & Company, Boston 1964. Reprint: 1985, ISBN 0-316-61166-2 .

- Jules Verne : Les Révoltés de la Bounty ( short story ), published in 1879 as appendix to volume 18 of the Voyages extraordinaires The 500 million of the Begum in France.

- Günter Sachse : The mutiny on the Bounty. Roman, W. Fischer, Göttingen 1959.

- Charles B. Nordhoff and James N. Hall : The mutiny on the Bounty - ship without a harbor , island, Frankfurt am Main / Leipzig, 2006, ISBN 978-3-458-34908-2 .

Film adaptations

Theater productions

- World premiere of the mutiny on the Bounty in the Schauspielhaus Bochum on January 25, 2010 under the direction of Henner Kallmeyer .

The bounty in art and culture

The bounty as a coin motif

The bounty is the motif on the face of the vast majority of the Cook Islands investment coins .

literature

Source editions

- William Bligh and George Hamilton: Mutiny on the Bounty. Reported by William Bligh. The pirate hunt of Pandora. Records of Dr. George Hamilton . 1787-1792 . Newly edited and edited by Hermann Homann . Edition Erdmann in K. Thienemanns Verlag, Stuttgart 1983, 2nd edition 1997, ISBN 3-522-61000-8 .

- Paul Brunton (Ed.): Awake bold Bligh! William Bligh's Letters Describing the Mutiny on HMS Bounty. Allen & Unwin, North Sydney, NSW et al. 1989, ISBN 0-04-442123-0 .

- Christiane Conway: Letters from the Isle of Man. The Bounty Correspondence of Nessy and Peter Heywood. The Manx Experience, Onchan 2005, ISBN 1-873120-77-X .

- Irvin Anthony (Ed.): The Saga of the Bounty . GP Putnam's Sons, NY, 1935. / Dell Publishing Co., Inc., NY First Dell Printing Nov., 1961.

Representations

- Caroline Alexander: The Bounty. The real story of the mutiny on the Bounty. Berlin-Verlag, Berlin 2004, ISBN 3-8270-0163-3 . (Carefully researched book, English original title: The True Story of the Mutiny on the Bounty .)

- Greg Dening: Mr. Bligh's Bad Language. Passion, Power and Theater on the Bounty. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge et al. 1992, ISBN 0-521-38370-6 .

- Rolf E. Du Rietz: The Bias of Bligh: An Investigation into the Credibility of William Bligh's Version of the Bounty Mutiny . Dahlia, Uppsala 2003, ISBN 91-974094-4-8 .

- Gavin Kennedy: Captain Bligh. The Man and His Mutinies. Duckworth, London 1989, ISBN 0-7156-2231-5 .

- John McKay: Bounty . Delius Klasing, Bielefeld 1994, ISBN 3-7688-0865-3 . (Model building instructions with photos as well as perspective and three-dimensional drawings of all shipbuilding details.)

Web links

- Bounty in full swing. ( Memento from September 27, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) Replica from 1960 for the film The Mutiny on the Bounty (1962). The smaller dinghy is stowed inside the larger one. Unlike in most of the depictions, the Bounty carriesa Red Ensign here , which corresponded to ships under the direct order of the Admiralty. The form that was already outdated at the time - the George Cross was actually only used until 1707 - is speculative, the French national flag in the large top, the flag of the host country, is a concession to the current balance of power in the waters of Tahiti.

- Side, frame and side elevation of the bounty

- The Mutiny on the Bounty. The original source documents. ( Memento from January 2, 2013 in the web archive archive.today )

- The mutiny on the Bounty. German translation of some of the original documents from the National Archives in Kew, London.

- The logbooks - documentation

Individual evidence

- ↑ www.privy-council.org.uk ( Memento from June 11, 2011 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Bligh's Orders ( Memento of March 8, 2005 in the Internet Archive ) on law.umkc.edu (English)

- ↑ dailymail.co.uk

- ↑ Verdict and Sentence ( Memento of March 13, 2005 in the Internet Archive ) on law.umkc.edu (English)

- ^ Navy List .

- ^ Find a Grave .

- ↑ Connection - The Magazine of the Pacific Cooperation Foundation, Issue 17 from September-November 2008, Wellington New Zealand, p. 7 live.isitesoftware.co.nz ( Memento from May 22, 2010 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF; 3.7 MB )

- ↑ Luis Marden: I found the Bones of the Bounty. In: National Geographic Magazine, National Geographic Society Washington, DC, December 1957 issue

- ^ Expedition report on www.archaeology.org

- ↑ The Lily, HMS Bounty. winthrop.dk, archived from the original on February 22, 2012 ; Retrieved November 2, 2012 .

- ^ Society Friends of the Arts: Mutiny on the Bounty in the version of the Schauspielhaus Bochum

- ↑ The only true account of the greatest, most daring mutiny of all time - told in the words of the men who lived it ... According to The New York Times .

Coordinates: 25 ° 4 ′ 7.3 " S , 130 ° 5 ′ 42.5" W