Vercovicium

| Housesteads Castle | |

|---|---|

| Alternative name |

a ) Vercovicium, b) Borcovicus, c) Borcovicium, d) Velurtion |

| limes | Britain |

| section | Hadrian's Wall |

| Dating (occupancy) |

Hadrianic , 2nd to early 5th centuries AD |

| Type | Equestrian and cohort fort |

| unit |

a) Legio II Augusta , b) Cohors I Hamiorum sagittariorum , c) Cuneus Frisiorum Vercovicianorum , d) Numerus Hnaudifridi , e) Cohors I Tungrorum |

| size | Area: 1.5 ha |

| Construction | Stone construction |

| State of preservation | Square floor plan with rounded corners, fencing and numerous buildings inside, several layers of stone still visible |

| place | Bardon Mill |

| Geographical location | 55 ° 0 '46.8 " N , 2 ° 19' 51.6" W |

| Previous | Brocolitia Castle (east) |

| Subsequently | Aesica Fort (west) |

| Upstream | Vindolanda ( Stanegate ) (southwest) |

| Aerial view of the fort area |

|---|

| Webaviation |

|

Link to the picture |

Vercovicium or Borcovicium was a Roman auxiliary fort in Northumbria , in north-east England , Parish Bardon Mill (Housesteads Farm, Haydon Bridge), a district of the town of Hexham.

It belonged to the chain of fortresses of Hadrian's Wall ( per lineam valli ), which consisted of a total of 16 forts, and secured its central section. The camp was used by the military for about 300 years, probably from 122 to 400 AD. Vercovicium was built over the existing wall and a watchtower. The fort was repaired and rebuilt several times. Most of the wall remains visible today date from the late reign of Hadrian (around 138) and the 3rd century AD. In provincial Roman archeology , Housesteads is primarily known for the best-preserved communal latrine in Roman Britain. A civil settlement spread to the south and east of the camp. There is evidence of a building with an apse from post-Roman times . The remains of a fortified farmhouse ( bastle ) from the late Middle Ages can still be seen at the south gate . Due to its well-preserved fortifications, the civil settlement and some Romano-British cult sites, Housesteads is one of the most interesting archaeological sites in Great Britain .

Surname

The ancient place name probably referred primarily to the civil settlement south of the fort. An altar inscription found at the fort, dedicated by the Frisian cohort to Mars Thincsus and the Alaisiagae , contains the letters "VER". It probably means "the settlement on the slope" (Latin: vergere = inclination + vicus = village / settlement). The fort also seems to have been called Vercovicium by the Romans . In the Notitia dignitatum , a directory of the highest Roman state offices from the early fifth century, it is entered as Borcovicium or Borcovicus . In the cosmography of the geographer of Ravenna , the place is recorded as Velurtion . The prescription Boraus Ver is evident from the inscription . The earliest mention of the current place name House Steads (the permanent house) dates back to the 16th century, when Nicholas Crane of Bradley built a fortified farm building, a so-called Bastle house, within the ruins of the south gate .

location

Housesteads is the eighth link in the fortress chain of Hadrian's Wall ( vallum aelium ) and secured its middle section. The fort stood directly on a ridge of the Whin Sills, at the eastern end of the approximately 1.6 km long Whinstone Crag between the valley of Knag Burn in the east and that of Bradley Burn in the west, about 8.5 km west of Carrawburgh . Its area slopes slightly to the south and west. From there you had an excellent view of the surrounding area. In the late 2nd century the region around Vercovicium belonged to the province of Britannia inferior , from the 4th century to the province of Britannia secunda .

Research history

Housesteads is the most important fort on Hadrian's Wall for archeology. Its area has been explored since the 18th century. In 1708 a visitor to the fort - whose name is no longer known - noted that the civil settlement stretched 700 yards from east to west and 400 yards from north to south. The antiquarian Alexander Gordon described the remains of streets of the vicus in 1724 . There are more early illustrations ( watercolors and drawings) of Housesteads than of any other camp on the wall. In particular, the historian William Stukeley , who visited Housesteads in 1725, aroused the general public's interest in the castle ruins with his sketches and description of the site (published in 1776 in the Itinerarium Curiosum ) and referred to them as the " Tadmor of Britain ".

It was one of the five fortifications that came into the possession of the archaeologist John Clayton in the 18th century . As part of his Roman Wall Estate , the fort was one of the earliest attempts in Great Britain to excavate Roman architectural monuments from a scientific point of view, to preserve them and thus to preserve them for future generations. Clayton, also a successful lawyer and town clerk of Newcastle a. T., gradually began to buy up lands around the wall in order to put an end to the constant stone robbery there. Later he had Roman buildings partially restored. He was also one of the founders of modern archeology on Hadrian's Wall. He made a special contribution to the preservation of the Roman monuments in the central part of the wall. This best-preserved section of the wall is still known today as the "Clayton Wall". The fort became a fixed point in the visiting programs of the most important antiquarians in England. In 1801, William Hutton reported, among other things, of "twenty streets in a very large suburb" that he counted on the site of the vicus . This meant the artificially raised terraces on which the residential buildings had once been built. The first test excavations at the fort took place between 1822 and 1831 on the initiative of pastor John Hodgson. He recorded his impressions in numerous illustrations in his notebooks. The first photographs of the camp (west gate) were taken in 1886. Further excavations were carried out from 1898 to 1910. In 1904, RC Bosanquet drew up the first overall plan of the fort.

The only major excavation campaign in the vicus was started by Eric Birley in the early 1930s. Of the 27 known buildings, only six have been completely excavated. In 1930, GM Trevelyan acquired the fort area and then handed it over to the custody of the National Trust , which established a museum to store and display the finds. In 1945 Frank Simpson and Ian Richmond carried out an excavation on the north wall and discovered the foundations of the wall and those of watchtower 36B. The museum was opened in 1951 and initially operated by the Ministry of Works . In the same year a conservation program for the existing walls was initiated. Charles Anderson, foreman of the excavation team from the late 1950s to the early 1970s, took numerous photographs for this. In 1954, D. Smith researched the camp's principia . From 1974 to 1981 the camp was examined by Charles Daniels, John Gilliam and James Crow (Newcastle University). In doing so, the north-east fortification of the fort was almost completely exposed. In 1976, James Crow discovered a Roman aqueduct that started from a well at the foot of Chapel Hill. In 1987, Crow examined the terraces between Housesteads Farm and the museum building, and a year later the wall gate at Knag Burn. The results of these excavations were evaluated with the excavations carried out between 1959 and 1961 by employees of Durham University (headed by John Wilkes). This enabled an almost complete plan of the north-eastern part of the camp to be drawn up. The investigations mainly focused on buildings XIII (commandant's house), XIV and XV (crew barracks and warehouse in the northeast sector) as well as sections of the camp fence between the north and east gates. In 1995, Peter Hill was able to use wall plaster analyzes to prove that the fort's gates had to be interrupted twice. Numerous inscriptions and sculptures recovered there offered a comprehensive insight into the life and beliefs of the Roman occupation. Some buildings of the civil settlement and temples outside the fort walls were also examined more closely. A large number of animal bones have also been exposed during the excavations over the years. They came from oxen, sheep, pigs and deer. A geophysical survey of the vicus was carried out in April 2003.

Today the museum and fort are looked after by the English Heritage . Other finds from the excavations at Housesteads are in the collections of the Museum in Chesters and the Museum of Antiquities in Newcastle upon Tyne . The fortifications and some inner buildings have been completely excavated and preserved. The foundations of most of the buildings in the vicus were filled in again.

development

2nd century

In 122, Emperor Hadrian ordered a barrier wall to be built in northern Britain, reinforced by watchtowers and forts, from the Tyne to the Solway Firth, to protect the British provinces from the constant incursions of the Picts from the north. Most of the wall was built by soldiers from the three legions stationed in Britain and the Classis Britannica .

The fort was probably built at the same time as the wall or shortly afterwards and is one of the first forts on the vallum aelium . There is evidence of pre-Roman settlement activity at Housesteads. Traces of agricultural activity (so-called cord rig cultivation, a cultivation method in prehistoric Britain) have been discovered under building XIII. The first Roman structures to be completed on this site were those of Hadrian's Wall along the northern edge of the Whin Sills ridge. The cliff edge near Housteads particularly favored the defense of the north flank of the fort. Its orientation suggests that the camp was primarily intended to prevent incursions by northern British tribes at the Knag Burn valley cut. It was also intended to replace one of the old Stanegate camps, Vindolanda , which was about three kilometers away. Another advantage of this location was the abundant sand and limestone deposits that could be mined in the immediate vicinity (traces of several Roman quarries and lime kilns).

Construction of the fortress began before the wall at Housesteads or Mile Fort 37 was continued to the west. A cremation grave in the northwest corner suggests that more than a year passed between them. The deceased were always buried outside the forts and settlements. The cremation grave must have been created before it was built. Work on the wall at Housesteads did not resume until the fort walls were fully built. At 138, at the end of Hadrian's reign, around 10,000 men were stationed on the wall. The archaeological evidence suggests a relatively peaceful section of the border. Four years after his death, his successor, Antoninus Pius (138-161), ordered the construction of a second wall ( vallum antonini ) on the Forth-Clyde-Isthmus in Scotland. Almost the entire crew of Hadrian's Wall was then transferred to Antonine Wall. Most of the soldiers of the Tungrian cohort were posted further north to Castlecary Fort. However, the excavations at Housesteads provided no evidence that it was completely abandoned. The camp was still occupied by soldiers. An inscription dedicated to the god Cocidius , probably from the late 2nd century, reports that u. a. Legionaries performed their "garrison service". From 160 onwards, the Antonine Wall was gradually abandoned. The border troops were moved back to Hadrian's Wall. The Tungrian cohort was now back in Housesteads and remained there until the end of Roman rule over Britain.

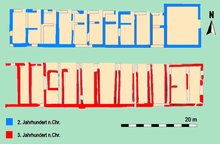

3rd century

In the period from the later 2nd to the early 3rd century, the fort was extensively rebuilt and repaired. In contrast to some camps on the Saxon coast , Vercovicium was renewed exactly according to the traditional Hadrianic model. The civil settlement ( vicus ) in front of the fort is likely to have reached its greatest extent during this time. Towards the end of the 3rd century the team barracks were converted into single accommodation. The fort's defenses were also extensively renovated. The civil settlement was largely abandoned soon afterwards. Since the occupation had probably already been reduced considerably by this time, its inhabitants, who were increasingly endangered by barbarian incursions, fled behind the fort walls and moved into the buildings no longer needed by the soldiers.

4th century

The last known inscription from Housesteads dates from the year 300. It is only a fragmentary dedication to the reigning emperor. It was probably the building inscription of Building XV that stood at the east gate. The last written mention of the Roman occupation is in the Notitia dignitatum from the early 5th century . Presumably the camp was used by the military up to this time. Around AD 400 the crew was likely to have consisted of only two or three hundred men. During this time, the camp headquarters was used as an armory and blacksmith's workshop. a. Arrowheads were produced.

5th century

When Roman rule in Britain collapsed around 407, part of the regular occupation also withdrew from Hadrian's Wall. The last Romano-British residents are likely to have left the fort around 430. In the excavation layers of the late 5th or 6th century, no more Roman finds were detectable.

Post Roman time

A clue for post-Roman settlement activities at Housesteads could be a stone box grave in a former cistern near the north wall. Next to it were the remains of an apse - in shape and size it resembled the remains of a wall in Vindolanda - which were identified as part of an early Christian church. There are no records of Housesteads in later medieval sources. In the centuries following the abandonment of the Roman border wall, Housesteads was nothing more than a chaotic field of rubble that was visited for summer grazing or hunting. The border between England and Scotland now ran from the mouth of the Tweed at Berwick to the Solway Firth north of Carlisle . From the 16th to the 17th centuries, the place was notorious as a shelter for cattle thieves and highwaymen. So-called Border Reivers from the clans of the Grahams, the Kerrs and the Armstrongs made the border area to Scotland and Yorkshire unsafe. One of the earliest explorers of Hadrian's Wall, William Camden , visited some of the ruins in the central sector of the wall around 1600 but avoided Housesteads for fear of being mugged and robbed there. The Housesteadsfarm was acquired in 1698 by a Thomas Gibson from nearby Hexham . Its previous owner, the leader of the Border Reivers , Nicholas Armstrong, was hanged in 1704. This was the beginning of a new era that gave everyone safe access to the castle ruins. Within a few decades, the archaeological site became known far beyond Great Britain. From the 18th century it became one of the most popular destinations for visitors to Hadrian's Wall.

Fort

The multi-phase fort was rebuilt several times during its period of use (around 197, 296 and 367). It had the square floor plan with rounded corners, which was typical of the middle imperial era, measured 180 × 110 meters and covered an area of 2.2 hectares. The two main streets of the camp, via principalis and via praetoria , divided the internal area into three parts, all of which were built with stone buildings. Its area drops sharply from west to south. The north wall runs along a steep edge of the terrain. Therefore, in contrast to most of the fortifications, the long axis of the camp extends from east to west (exact alignment east-north-east-west-south-west). Nevertheless, one of its gates also opens to the north. Due to the steep slope, its praedentura does not protrude over the wall. The defenses were renovated in the late third century or early fourth century or supplemented with intermediate towers. During this time there were also major structural changes to the team barracks and a large warehouse was added. The last repairs carried out by the regular military were made in the 4th century. This includes the installation of a heated bath in the warehouse at the east gate. The hospital and the granary were converted into housing for the civilian population. However, there are some indications of later repairs to the fortress, which were not abandoned by its inhabitants even after the end of Roman rule. Due to its relatively remote location, Housesteads was not as excessively exposed to stone robbery as the ramparts on the plains.

Enclosure

The fortification of the camp was almost completely exposed and preserved. The relatively narrow stone wall, only 1.3 meters wide, was supported on its back by an approx. 6 meter wide earth ramp, which also served as a battlement. It consisted of a quarry stone core, encased on the front and back with cut sandstone blocks, which were connected with lime mortar. In the south-east corner, the remains of a staircase were found that were still four rows of stones high. Judging by the height of the steps, the wall might have been up to four meters high. Repairs to the north and south walls were made towards the end of the 2nd century due to the instability of the foundations. The ovens were placed in the embankment behind the wall, as far as possible from the barracks. The rule was probably one oven for each barracks block. There was a larger bakery on the southwest corner tower. Platforms for heavy slinging arrows may also have been added to the ramparts in the early third century. In the event of an attack, the soldiers were able to quickly reach their assigned defensive positions on the wall via a street that ran around the entire camp ( via sagularis ). The north wall stood on unsafe ground and therefore threatened to collapse. For this reason, a 1.4-meter-wide retaining wall was added at around 300 meters, and the earth wall was rebuilt on its back. After the collapse of the north wall and the retaining wall between the north gate and the northeast corner tower, around the middle of the 4th century, it was replaced there by an earth wall with a palisade .

Towers

The fort was additionally reinforced at each of its corners with a square tower attached to the inside. The entrances were on the ground floor. It is not known whether there were stone stairwells or only wooden ladders. Hearths have also been found in some of the towers. During the excavations, a bakery equipped with two ovens was discovered in the tower in the southeast corner. The tower in the northeast corner was replaced by another example in the 2nd century, which was connected directly to Hadrian's Wall a little further west of the corner of the fort. A channel ran out of it, presumably the drain for a latrine. Between the gates and the corner towers, intermediate towers were built into the western section of the north and south walls. The Hadrianic fort only had two of these intermediate towers. The remaining four on the east side of the fort were slightly smaller and were only added in the fourth century. The stone intermediate tower on the north wall was replaced by a wooden structure in late antiquity. The southern towers were also rebuilt in wood and were not connected to the wall. The towers were probably ten meters high. It is difficult to say whether the upper floor was covered with a roof or open and provided with a crenellated crown. So far, there are no relevant archaeological finds in order to be able to reconstruct their appearance beyond doubt.

Gates

The camp could be entered through four gates of approximately the same size in the north, south, west and east. The western and eastern gates of the fort were placed centrally on the narrow sides. The locations of the north and south gates on the long sides, on the other hand, were shifted to the east about two thirds of the distance to the western end. All were flanked by two square towers. The passages on the north and south walls were offset slightly to the east. All had been planned and set up according to a uniform scheme. Each gate had two passages, separated by two support pillars ( spina ) on the front and back. The guard rooms were in the flank towers. Fragments of the facade decoration suggest that a battlement walked over the passages. It is unclear whether it was also covered. Some roof tiles were found, but these could also come from a post-ancient period. In Housesteads, the gates were set back slightly from the wall and could be locked on both sides with double-leaf wooden gates. In the 4th century the gates were repaired again.

North gate

Through the north gate opened into the tribal areas of the Picts north of the Wall. It is one of the best preserved gates in the fort. The central pillar stands upright five rows of stones. At the back of the western flank tower you can still see a stone water tank in which the rainwater running off the roof should collect. The steep slope in the north was impossible for wagons to pass. Only pedestrians or at best riders could manage the climb to the north gate. Later attempts were made to make access to the western passage a little easier by building a stone ramp. It also got a slightly higher stone threshold. One of the pivot stones was inside the fort. The eastern passage was apparently rarely used. Later the gate was partially demolished. The eastern passage was blocked with the stones. This is also were spoils used, including a fragment of a Iupiteraltars (now in Chester Museum). The pivot stones had not been removed. The gate was probably not used for border traffic beyond the 2nd century, after that it was probably only used as a kind of slip gate . Presumably, from the 4th century onwards, all border traffic was ad muros , i.e. H. handled via the separate wall gate at Knag Burn . From there, a road that climbed only slightly led to the east gate of the fort.

South gate

The gate had two passages and consisted of massive, hand-made stone blocks. Via Principalis , which begins at the south gate , you got directly to the granary and the north gate. Its right passage was later walled up. In the 16th century, a fortified farmhouse ('Bastle') was built over the eastern flank tower, facing north to south. To the north of the gate, inside the fort, there was a long rectangular house of the same time. Nothing can be seen of him today. In the 17th and 18th centuries Torruine was a kiln used.

West gate

The gate was built with massive stone blocks, much larger than those used to build the wall. You can still see the holes for the gate hinges and the curbstones . Via Decumana began at the west gate and led to the hospital. It is the best preserved fort gate on Hadrian's Wall. One of the reasons could be that it fell out of use in the Valentinian's reign around 300 and its two passageways were bricked up. The north portal, which was only blocked with quarry stones, was probably only built around 369. The threshold and doorstop of the south portal date from the Severan period. The guard rooms were equipped with heaters at a later date.

East gate

The east gate (main gate of the fort) had two passageways, the camp road from there ( via Praetoria ) led directly to the camp headquarters. In the passage a fragment of a relief of the Roman goddess of victory Victoria was found in 1852 . This relief and probably other representations of gods (possibly those of Mars ) were placed in niches above the outer archway. They probably flanked a plaque on which the building inscription was carved. Pivot stones and stone sleepers in the northern passage were renewed in Severan times. In the late period, a canal was built under the passage. The pivot stones of the gate leaves and the ruts of the wagon wheels can still be seen on the gate ruins. There, too, the southern archway was later walled up. For this purpose, stones from the gate were used. The passage behind it was possibly used as a guardhouse afterwards. This suggests that it was allowed to decay as early as Roman times. When the guardroom in the south tower was uncovered, a large heap of coal was found. Apparently the tower was only used as a storage room in its later phase.

Interior development

Six elongated barracks blocks ( contubernia ) occupied the pretentura and six the retentura ; in the center, from south to north, were the administration building ( principia ), two warehouses ( horreum ), the commandant's house ( praetorium ) and some other functional buildings. The warehouse area was divided into three sectors. Six barracks were aligned with the long axis of the fort and stood in the eastern and western third of the inner area. The commandant's house, the warehouse, the administration building and the hospital faced the short sides and occupied the central third of the fort. The north-south road ( via Principalis ) separated the six eastern barracks from the center. Metalworking workshops ( fabrica ) from the 3rd century were found along the fort walls . Weapons and armor were not only repaired there, but also produced.

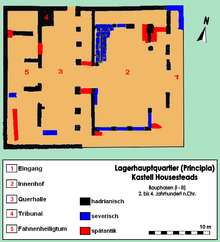

Camp headquarters

The multi-phase administrative center ( principia ) was built when the fort was founded and was rebuilt in the 3rd and 4th centuries. The single-storey building (in the plan building X) was divided into three parts, an atrium, a cross hall ( basilica ), an eastern aisle and three extensions to the west, where the writing rooms ( officia ) of warehouse management and the regimental shrine ( aedes were accommodated) . As the fort area slopes down from north to south, it was built on an artificially raised terrace. For this reason, the area of the Principia was somewhat smaller (approx. 632 m²) than that in the other forts on Hadrian's Wall. In the camp headquarters the standard bearer of the unit ( signifer ) and his adjutant, the cornicularius , both acted as paymasters.

The main entrance opened to the east on via praetoria . A large fragment of a relief depicting the god of war Mars was found in the immediate vicinity. It was probably part of a larger stone tablet that was attached to the main entrance. The forecourt was surrounded on three sides by colonnades. During the later renovations, the colonnades in the courtyard were bricked up. An archway in the side aisle led to the transverse hall. It could also be entered through small gates in the north wall and at the southern end of the east wall. Six pillars inside separated the aisle from the hall. It was higher than anything the aisle and probably with a gable roof covered. Presumably, several glass windows on the top of the walls lit the interior. It served as a meeting and drill room and had a raised platform ( tribunal ) at its northwestern end , from which the camp commandant could make his statements to the troops.

The western extensions consisted of five rooms that housed the office of the camp administration and the flag sanctuary, which was the same height as the transverse hall. Since the subsoil there consisted of massive rock, the installation of a basement room, which normally housed the troop coffers, was dispensed with. Two office rooms were probably built on both sides (north, south). The standard of unity, an imperial statue and altars for the highest imperial gods were set up in the flag shrine. It was probably physically separated from the hall by a barrier made of decorated stone slabs. However, no copy of these records has been preserved in Housesteads. Such a separation is known from the Principia of Vindolanda . There were also holes carved into the plates there, which probably served as a holder for a metal grille. The troop treasury was housed in another secure room. A heating system was later installed in the western extension, and the chambers were probably raised by one floor. Weapons were probably also stored here ( armamentarium ). One found u. a. More than 800 iron arrowheads, sometimes with fragments of the wooden shafts stuck in them.

Praetorium

As a member of the knighthood ( equester ordo ), the camp commandant claimed the largest and best-equipped quarters in the fort (building XII). It was a multi-phase atrium house built in the Italian-Mediterranean style , i. H. all rooms were arranged around a small inner courtyard ( peristyle ). The house was also built in the founding phase of the fort and was rebuilt in the 3rd century. The main entrance was centrally located on the eastern (sheltered) side. The outer walls were simple and without any architectural decoration. The building had no other floor. The north, west and part of the east wing date from the time of Hadrian, the south and east wings are late antique. The rest of the building was probably only made of wood at first, but was later also rebuilt in stone. From the entrance you got directly into the inner courtyard, which was probably surrounded on all four sides by colonnades ( portico ). Nothing was left of them when the building was uncovered. However, reused fragments of columns were found in the hypocaust of the north wing. The rooms on the north and west side served as living quarters ( cubiculum ) for the commandant and his family. The kitchen ( cocina ), equipped with a masonry table stove and an oven, was in the northeast corner. Some of the rooms had obviously been remodeled several times. The dining room ( triclinium ) in the north wing could be heated by means of hypocausts. The latrine was in the northwest corner of the building. The feces were washed away via a sewer. There were coins, a golden signet ring and broken glass from bowls and various other vessels. The accommodation of the house staff and the stables were housed in the other two wings of the building. In contrast to the commanders quarters in other forts on the wall, no bathing room could be detected in the praetorium of Housesteads. It is unclear whether an apse at the southern end of the adjacent building XI belonged to such a bath.

Camp hospital

The multi-phase valetudinarium (building XI) was north of the Praetorium and west of the Principia. The phase I building was built in the 2nd century, and was rebuilt again in the 3rd century. It was oriented from north to south and consisted of four side wings that were grouped around a courtyard. The inner courtyard was surrounded by a low wall that served as the base of a portico. A long rectangular room in the north wing could have served as a medical room. The other sides were surrounded by smaller rooms, and a latrine was built into the southwest corner. Possibly the hospital still had an upper floor, a room on the SE side was very narrow and could have served as a staircase. Finds such as B. Medical instruments that could confirm the assumption of the archaeologists are missing. The fact that the fort had a hospital was interpreted from the inscription on a tombstone that had been set for an officer- grade surgeon ( medicus ordinarius ) of the Tungrian cohort, Anicius Ingenuus. But the arrangement of the rooms and the remains of the sanitary facilities make it unlikely that the building was used as a workshop, warehouse or similar.

Warehouses

The function of the multi-phase, east-west oriented Building VIII could be clearly identified by its distinctive structural features. It was a type B - d warehouse. H. it was free-standing inside the fort. In phase I a single large warehouse ( horreum ) was built on this site and later in phase II ( Severan ) it was divided lengthways by two walls into two halves of the same size with their own outer walls and roofing. It stood at the highest and therefore driest point of the fort and had a long rectangular floor plan. The massive outer walls were supported by fifteen pilasters . The wooden planks of the floors had been placed on several rows of stone pillars. In the lower area of the side walls there were slot-like openings to allow air to circulate to the outside. This should keep the grain and other goods deposited there dry and cool. The southern pillars of the northern Horreum were based on fragments of columns that could have come from the courtyard of the Principia. The reconstruction of the superstructure and the condition of the interior are speculative. The grain was probably stored in a number of specially made wooden crates on both sides, which were accessible via a central aisle. It would also be possible that it was packed in sacks and stacked. The two main entrances, each with a loading ramp, were on the via principalis , at the short, western end of the building.

Building XV and storage bath

The remains of this multi-phase building (four construction periods) still visible today probably date from the end of the third century. Presumably it was used as storage for grain, other food or weapons. Possibly the taxes in kind of the annona militaris to be paid by the population were stored there. Stone blocks marked with notches can be seen on the south wall of the building. These markings were supposed to ensure that the bricks were hoisted into the correct position on the wall by the construction workers. In the late 4th century, a small bath (balneum ) was installed in the northeast corner of the building , which was supposed to replace the thermal bath outside the fort walls. It consisted of two rooms. Room I served as a changing room and cold bath, the water basin was in the northeast. The hot bath, which was equipped with a hypocaust heater, was located in room II. The pool of water stood on the east wall. Only a few stone pillars that once supported the floor are left of the heating system. Limestones at the northern end, reddened by the heat, mark the fireplace ( praefurnium ), which heated the bath water in a bronze kettle.

Barracks

The fort crew was housed in 13 barracks blocks. They were distributed over the eastern and western parts of the fortress, had a long rectangular floor plan and were parallel to the long axis of the fort. Three of them, Buildings XIII, XIV and XV, have been completely excavated and are still visible. Their foundations were made of sandstone, the rising was probably built using truss technology with partitions made of wickerwork and clay. At the front, the buildings had verandas that were supported by wooden or stone pillars. The line of the pillars was marked by a gutter that was supposed to drain the rainwater. The buildings were arranged in pairs, facing each other, so that a small courtyard lay between them. At the western and the eastern ends there were multi-roomed so-called head buildings in which the NCOs ( centurion , optio ) were accommodated. The head structures of the eastern barracks were a little lower for topographical reasons. Ten residential units ( papilio ) were available per block for the soldiers . Buildings IV and XV, although very similar to barracks, are likely to have been used as a forge and warehouse (the latter perhaps as the armory of the fort). Towards the end of the 3rd century AD, extensive alterations were made to the team barracks.

Building XIII: This team barracks was probably built in Hadrianic times, probably around 124, and was in use for almost 200 years. It was divided into ten residential units, consisting of two chambers, and offered space for a centurion, i.e. s. 80 men. The centurion was housed in a slightly larger living unit. A stone water tank stood between the barracks and the north wall, in which the rainwater was collected from the roof of the building. Between the 2nd and 3rd centuries, small changes were made to the interior. They were particularly easy to recognize in the centurion's quarters.

Building XIV: The remains that have survived date from the late 3rd century. During this time, the previous Hadrianic building was torn down and replaced by a series of detached, chalet-like huts, five for the common soldiers and one larger for the officer. A smaller house at the end of the row was used as a workshop. Similar specimens could also be observed in the neighboring Aesica Fort . The rooms, arranged in pairs, based on the classic design ( contubernium ) were given their own outer walls and roof and were separated from one another by a narrow passage. These accommodations measure eight to twelve meters in length and 3.6 to 15.15 meters in width. The number of these buildings, most of which also had their own fireplace or stove, was less than the chambers of the barracks block of the 2nd century, as the late antique units were increasingly thinned out in terms of personnel. Such dwellings were easier to build and maintain than the old and dilapidated half-timbered barracks to be made habitable again. It is estimated that there was room for two soldiers. There was no clear evidence that the men lived there with their families.

Latrines

Remains of toilets ( lavatrina ) were found in the Praetorium and in the hospital. Discharge could be detected in the head structures of the barracks in which the centurions were housed, as well as in the northeast corner tower. A large communal latrine was located at the southeast corner of the camp wall, at the lowest point of the fort area. The building had a long rectangular floor plan and essentially consisted of the four outer walls, a U-shaped sewer and the central stone platform. The entrance was on the east side. It was probably covered with a pent roof sloping to the north. The faeces were rinsed out again with rainwater from three higher cisterns (two on the southeast corner tower, the third west of the latrine) through the sloping (incline of 1.5 m by 1 m), counterclockwise around the platform. The cisterns were filled with rainwater from the street canals. The water entered the canal through two stone overflow channels on the north wall of the latrine, the segments of which were sealed with lead. The outlet was located next to the southeast corner tower. The beam holes on which the seats on the north and south sides were mounted can still be seen in the wall. What material they were made of, wood or stone (as in the Segedunum fort ), is unknown. A wooden specimen was also uncovered in Vindolanda . Presumably it was a continuous construction with keyhole-shaped openings. Sponges attached to wooden sticks ( spongia longa or tersorium ) were perhaps used for cleaning . It was a community tool that was cleaned in a gutter with running water in front of the latrines and then placed in a bucket of vinegar for the next user to use. They served the same purpose as today's toilet paper. Probably the soldiers in Housesteads only used simple moss, since sponges would have had to be imported from far away and expensive. There were two stone troughs and two water grooves on the platform. The cleaning sticks were washed out in them. As a result, the grooves wore so much over time that they finally became unusable. The stone troughs are therefore likely to have been erected later. They were originally fed from a pressurized water pipe. It is believed that there was another latrine in the (as yet unexplored) southwest part of the fort.

Water supply

Since no running water crossed the fort, the rainwater had to be collected. Seven cisterns were found along the fort wall. They were put together from second-used stone slabs, the gaps were sealed with lead and the floor with a waterproof mortar. At the top they were joined with iron clips. On the edges one could often observe grinding marks, which might have been created when sharpening blades or spearheads. A few cisterns stood on the back wall of the towers, where they were supposed to catch the running water from the roofs. The rest of the water was caught by the running water from the camp roads. If there was insufficient precipitation, the additional water required could be obtained from a stream, the Knag Burn, flowing through the incision in the ridge east of the fort. The largest cistern, with a capacity of over 2000 liters, was located on the southeast corner tower.

garrison

Several auxiliary units were stationed in Vercovicium during its existence. Their names could be identified from the numerous epigraphic sources that were found there. In the 2nd century there was initially a cohort of around 1,000 auxiliary troops, unknown by name. It was later replaced by soldiers of the Legio II Augusta , one of the rare cases where legionaries were relocated to an auxiliary fort as a garrison on the Wall. In the 3rd century there were two Germanic cohorts. From late antiquity onwards, the fort was occupied by the Limitanei .

The following units provided the crew for the fort or may have stayed in Vercovicium for some time :

| Time position | Troop name | description |

|---|---|---|

| 2nd century AD |

Legio secundae Augusta (the second Augustan legion) |

The members of this legion were not permanently stationed there, their vexillations were probably mainly occupied with construction work. Many of the Housesteads altar inscriptions attest to their presence. The Legio II donated u. a. an altar for the supreme imperial god Iupiter. The legionaries, who were also highly skilled in their craftsmanship, were responsible for the construction of the vast majority of the Roman military installations on Hadrian's Wall. It is therefore almost certain that they also built the stone walls and internal buildings of the Vercovicium camp. In the 140s the border of the Roman Empire was moved further north to the Antonine Wall. The fort crew also seems to have been posted there. Housesteads may have been occupied by August II legionnaires until the return of the border troops in 162 . |

| 2nd century AD |

Legio sextae Victrix (the sixth legion, the victorious) |

The soldiers of the Sixth Legion commissioned an altar for the Romano-British deity Cocidius and another for a god whose name was unknown. |

| 2nd century AD |

Cohors prima Hamiorum sagittariorum (the first cohort of archers from Hama) |

The unit was originally set up in the east of the empire, on the outskirts of the city of Hama , Syria province . Your soldiers very likely participated in the invasion of Britain in 43. The Syrians were then stationed in Carvoran ( Maglione ) and in Bar Hill on the Antonine Wall. The unit may also have been in Housesteads for a period of time. Their presence there is only attested by an unlabeled tombstone from the 2nd century with a relief of an archer (now Museum of antiquities, Newcastle upon Tyne). The soldier is shown in a short tunic, with a pointed helmet on his head and a cloak around his shoulders. On the left you can see his reflex bow ( composite bow ), he wears a dagger on his belt and a hatchet in his right hand. The quiver of arrows was hung over the right shoulder with a strap. It is possible that only a smaller division of this force was stationed there. The unit was also in the Carvoran in the late 2nd century . It is so far the only Roman archery unit known for Britain. |

| 3rd century AD |

Cuneus Frisiorum Vercovicianorum ("a division of Frisians ") |

At the end of the third century riders of Germanic descent were possibly also housed in the fort, recruited from tribes that settled in the area around the Civitas Tuihanti , now the Twente region in the Netherlands. The stay of such a unit in Housesteads is known from a single inscription found there on an altar dedicated to the god of war Mars Thincusus and the Alaisiagae. Another altar was commissioned by Frisian tribesmen ( cives Tuihanti ), but the troop is not mentioned in the inscription. The presence of other Frisian equestrian formations is also attested for the British castles Aballava , Derventio (Papcastle, Cumbria) and Vinovia (Binchester, Durham). |

| 3rd to 4th century AD |

Numerus Hnaudifridi ("the band of Notfried") |

These Germanic mercenaries are also only mentioned on an altar for the Alaisagae. It is believed that these men were irregulars. This unit could also have emerged from the Frisian equestrian troop. Their first commanding officer was probably an officer named Hnaudifridius, perhaps a Frisian tribesman. |

| 3rd to 5th century AD |

Cohors prima Tungrorum milliaria (the first cohort of Tungerer , 1000 strong) |

This auxiliary troop cohort was originally recruited from Germanic tribes who settled in the area around the city of Tongeren in what is now Belgium (province of Gallia Belgica ). The unit was previously stationed at the nearby Stanegate fort in Vindolanda and was also mentioned on the Vindolanda tablets . Their crew strength is only given as 752 men including the officers. The exact time of their march to Housesteads is not known. Presumably it was moved there after a large-scale renovation of the fort around 200 AD. The cohort is mentioned on at least eleven inscriptions from Housesteads and its environs; three altar stones are dedicated to the god Jupiter and others to Mars, Silvanus, Hercules and the mother goddesses (matrons). A tombstone reports the battle death of a legionary centurion who probably commanded the cohort at the time of Hadrian (117-138). Further evidence of the presence of the Tungrians is derived from two other inscriptions. A building inscription contains the initials of the cohort, which were discovered in the foundations of the granary, one of the original buildings of the Hadrianic fortress, which was renovated in 205-208. The second inscription is a dedication to the “gods and goddesses”, probably the oracle of Apollo in Claros, western Turkey. From the Notitia dignitatum , the list of troops of the Dux Britanniarum , the rank of their commanding officer, a tribunus , is known for the 4th century . Since the troops still appear in this late antique document, they could have stood there until the final withdrawal of the Roman army from Hadrian's Wall. |

Hadrian's Wall

The long axis of the fortress runs parallel to Hadrian's Wall. Due to the topography, it forms the northern fort wall. According to building inscriptions (centurial stones) found on the wall between Housesteads and Cawfields, the 1st cohort of Julius Candidus and a centurion under the command of Gellius Philippus were involved in the construction. Presumably these units belonged to the Legio II Augusta . The earliest building structure in this sector of the wall was the watchtower 36B . It was located 30 meters west of the north gate between the fort wall and building VI and was demolished together with the wall when the fort was built. Its foundation walls can still be seen. Hadrian's Wall itself was built there in the narrow version on a wide foundation. The north wall, moved a few meters further north, was later built with their building materials. The rest of the wall was connected to the corner towers in the northwest and northeast. The northeast corner tower was rebuilt a little further to the west.

The military road accompanying the wall on its south side met the fort at the east and west gates. From the west gate you could get to Mile Fort 37, 400 meters away .

Since the steep ascent to the north gate of the fort was not or only with difficulty passable for wagons and riders, a border control post ( Walltor Knag Burn ) was set up in a valley to the east of the fort in the 4th century . A stream (Knag Burn) crosses under the wall through a recess to the west of the gate. It is one of the few passages on the wall outside of a mile fort or fort ( extra muros ).

Vicus

To the south, west and east, the fort was surrounded by a civil settlement ( vicus ). Their development peaked between the late third through the early fourth centuries. It was abandoned after barbarian invasions in the late fourth century. A considerable part of its inhabitants should not have fled, but rather hid behind the walls of the fortress. The archaeologists observed a number of structural changes to the internal buildings (e.g. on the Principia ) of the fort for the period in question, which probably had to be made to accommodate the newcomers. Since the regular occupation in the fourth century was probably only around 300 men, there was plenty of space in the camp. Roman vici usually did not have their own administrative apparatus or legal status and were assigned to the regional body of a civitas . An inscription discovered south of the fort suggests that council meetings were held in the settlement that were not under the supervision of the military.

The oldest buildings in the settlement were discovered south of the moat, i. H. still outside the military exclusion zone. In this way the fortress could be expanded if necessary, as happened in the Onnum fort at the beginning of the 3rd century. The foundations of twenty buildings were exposed in the 1930s. They were mainly lined up along a road running from north to south that connected the fort with the Stanegate and led from the moat to the south gate of the camp. They all came from the 3rd and 4th centuries. During the excavations, however, the exact year the settlement was founded could not be determined.

Due to the steep slope, the houses stood on artificially raised terraces and were used for residential purposes, as blacksmiths' workshops, shops, stables and taverns. They had a long rectangular floor plan (so-called strip houses ), their front side was aligned to the main streets. The majority of these were simple, one-story buildings, the wickerwork walls with clay plastering on rubble stone foundations. But some buildings were built entirely of stone. For its construction mainly stone from the vicinity of the fort was used. The west wall of a particularly solidly built house measured up to 1.8 meters at the base. Perhaps this building had a special function. The dwellings in the south-west area of the excavation area were of poor quality. The pottery found there was similar to specimens from Friesland. It is believed that the soldiers of the Tungrier cohort built the better equipped buildings of the vicus, while the much simpler buildings were inhabited by the families of the Frisian soldiers in the 3rd century. The plot boundaries had been marked by small ditches. To the south of the west gate, traces of a 105-by-97-meter, densely built-up annex of the vicus were found , which bordered the southern moat and was surrounded on the remaining three sides by a moat. Apparently access was only possible through a gate. Today only the preserved foundations of six buildings can be seen at the south gate. The positions of other buildings can still be seen at the east gate from their foundation trenches.

During the 1932 excavation, Eric Birley came across the skeletons of a middle-aged man and a woman under the clay floor of the back room in one of the houses examined, which consisted of an anteroom, probably a shop, facing the main street and a back room. The broken tip of a sword or knife blade was stuck between the ribs of the male skeleton. Under what circumstances the two died and who had just buried them there could not be clarified by the excavators. The later examination of the remains by a coroner led to the conclusion that the two must have died shortly before 367 AD. The building has since been known as the "Murder House".

Thermal bath

John Hodgson first described the remains of the bathhouse in 1822 and Robert Bosanquet examined them in 1898. The Housesteads bathhouse was - as with most Roman forts - because of the risk of fire outside the fortress walls, in this case about 90 meters east of the Fort on a terrace above the east bank of the Knag Burn. The approximately 10 x 8 meter building was only examined superficially and was only very poorly preserved when it was discovered due to the centuries-long stone robbery. A smaller exploratory excavation in 1932 showed that the bathhouse reached about 4.5 meters further north on its north side. One of the walls was still ten rows high. It probably resembled the Wallsend and Chesters specimens, and was believed to be shared by the crew and civilians. An access path led from the bath house to the east. Today the building can only be seen in aerial photographs.

Temple precinct

In addition to its military importance, Vercovicium was probably also one of the most important places of worship on Hadrian's Wall. Seven or eight temples and at least three shrines are attested to housesteads by altars. Five or six of the temples were on or near Chapel Hill. Known are a mithraeum, a temple of the Roman-Germanic deity Mars Thincsus and the Alaisiagae ("the all-honored"), a shrine for Silvanus and Cocidius, the matrons and - probably - a nymph shrine. Around thirty consecration altars have been unearthed in Housesteads. Most of them were dedicated to Jupiter Optimus Maximus, the supreme god of the Roman pantheon, closely followed by the god of war Mars, to whom seven altars alone had been donated. In addition to these two classical Roman gods, the Germanic god Hueterus (three altar stones) was worshiped there. The Persian god of light Mithras , particularly revered by the Roman soldiers, was represented with three examples, as was the Romano-British god Cocidius , again together with the Alaisiagae. The Greek god Hercules, the Roman forest god Silvanus and the matrons (mother goddesses) were also worshiped there. The dedication inscription could no longer be deciphered on four altars.

Nymphaeum

The spring sanctuary is south of the vicus on Chapel Hill. The excavators uncovered a small, semicircular, very simply executed cult site that measured 4.8 × 3.9 meters. A semicircular stone wall stood as an enclosure on the northwest side. In front of it, a spring rises at a depth of about 2 meters, which was bordered by four heavy stone slabs. Subsequently, two altars were found, but they did not have any inscriptions. Presumably a water deity or a whole group of deities, unknown by name, was worshiped there, including the water nymph Coventina known from the inscriptions of Carrawburgh ( Brocolitia ) . Finds of coins and pottery shards suggest that the cult site was created around the middle of the 2nd century. It is believed that it was used until the early 4th century.

Round temple of Mars Thincsus and the Alaisiagae

This cult building, which was structurally only very roughly executed, stood on Chapel Hill south of the fort. The foundations consisted of rubble stones mixed with earth and rubble. The entrance was decorated with a stone arch decorated in relief, on which the god of war and his companions as well as the goddess of victory Victoria were depicted. Its walls must have been drawn up in half-timbered houses. Inside it was 3.9 meters in diameter and covered an area of about 5.4 m². The temple was built in the early 3rd century over the ruins of one of the vicus workshop buildings, which was believed to have been destroyed during a barbarian invasion around 196. Inside were all the altars of Mars Thincsus known from Housesteads . They had been donated by the commanders and the soldiers of the auxiliary troop cohorts who had been stationed there over time. Some of the altars were dedicated to his companions, the Alaisiagae . All four, Beda, Fimmilena, Baudihillia and Friagabis are named on the altar inscriptions.

Mithraeum

The Mithras Shrine was discovered in 1822 west of Chapel Hill outside the fort. It was first excavated in 1898 by R. C. Bosanquet, who found several statues and reliefs in it. However, the excavation results were only poorly documented. In 1907, Collingwood Bruce stated in his manual on Hadrian's Wall that almost nothing was left of the Temple of Mithra. Later, employees of the Royal Commission of Heritage Memorial in England (RCHME), Newcastle section, also examined the place of worship. Lindsay Allason-Jones suggested that the temple was used as a residential building from the fourth century onwards. A bronze bracelet and a ring with a pearl were found in the building from this period.

The temple was about 14 meters long and 5.45 meters wide and - like most Mithraea on the continent - somewhat sunk into the ground. Its walls were made of bricks (maximum 66 cm high). But they were only plastered on the east side. The latest excavations have shown that the main room was still preceded by a vestibule on the east side. The main room consisted of a 2.65 meter wide central aisle. On both sides there were slightly raised side benches (width 1.65 meters). There were also traces of the support beams on the side walls. In the back of the cult room a 2.33 meter wide and 0.75 meter deep niche was built as a sanctuary , in which several altars and the Mithras relief were set up. The floor consisted of a brick covering. During the excavations, an overlying layer of clay was found in which wood and brick fragments were enclosed. Apparently the floor of the temple had been flooded for a long time. The water probably came from a spring on the north side of the building. It was collected in a brick basin (length 0.52 meters, width 0.37 meters, depth 0.45 meters). The excess water could be drained through two narrow channels. During the excavations, a layer of charcoal was found, probably the remains of the temple roof. The building had apparently been destroyed by fire.

The damage to the cult images was even more obvious than in Carrawburgh . The tauroctonia was found completely shattered; the heads of the statues of the torchbearers and of Aion had been cut off. The degree of weathering of the altars erected there showed that they must have been exposed to wind and weather for a long time. Only the relief of Mithras, which shows his birth from an egg , surrounded by an arch with the signs of the zodiac , was largely intact. It was placed in such a way that it could also be lit from behind. In 1900 an altar was found there which, according to the inscription, had been donated by two men, Gallus and Volusianus, the god of light around the year 252. The other two altars were dedicated to Iupiter and Cocidius and may have originally been erected in the temple of Mars Thincsus. The finds from the Mithraeum are on display in the Blackgate Museum in Newcastle upon-Tyne.

Matron shrine

The cult site is located south of the moat ( vallum ) and east of the fort, between the Knag Burn and the eastern connecting road to the Stanegate. Two altar stones were discovered there that were dedicated to the mother goddesses.

economy

In the area around Housesteads numerous traces of agricultural and craft activities have been found. A metal workshop was discovered in front of the east gate of the fort, south of the military road. Lime kilns stood in the area between the eastern fort wall and Knag Burn. In the surrounding hillsides there was intensive farming on field terraces, particularly along the slopes to the south of Housesteads. An egg-shaped quarry north-east of the fort, at the western end of the Kennel Crags, was first mistakenly viewed as an amphitheater . Apparently the building material for the fort buildings was broken there.

Burial grounds

At Housesteads two Roman cemeteries could be located; one southwest of the Mithraum and between the road to Stanegate and Knag Burn, southeast of the Matron's Shrine.

Early Christian burial chapel

During his excavation in 1898, Robert Bosanquet came across a 6 x 10 meter building with an apse , probably a kind of chapel, between the team barracks (Building I and Building VII) . What was unusual for such a building was that the apse was at its western end. Most of the early Christian churches had the apse on the east side. The floor consisted of large stone blocks and slab sandstone that were only roughly joined together. The west wall of the apse was best preserved. Today nothing can be seen of the chapel. In a water tank north of the building, west of tower 36 B, a burial place lined with simple stone slabs was found, probably an early Christian burial, as it was common from the 4th to the 8th century. This find supports the interpretation of the building remains as a burial chapel. Presumably it was built by the castle garrison towards the end of the 4th century and was still in use after the Roman soldiers had long since abandoned the camp.

Housesteads Museum

The museum was built in 1936 over the ruins of a house in the Roman civil settlement. His collection contains some of the finds and sculptures from excavations since the 1960s. The building was extensively renovated and the exhibition redesigned. The museum then reopened in May 2012.

See also

literature

- RP Sanderson: Survey of the Debateable and Border Lands adjoining the Realm of Scotland and Belonging to the Crown of England taken AD 1604. Alnwick 1891.

- William Camden: Britannia. 4th edition, London 1600.

- Wiliam Stukeley: A Cumulus of Roman Antiquitys at Housteads. 1725, published in the Itinerarium Curiosum. London 1776.

- John Hodgson: Observations on the Roman Station of Housesteads (= Archaeologia Aeliana: or miscellaneous tracts relating to antiquity. No. 1). 1822.

- J. Hodgson: Notebooks from the early 19th century. Society of Antiquaries of Newcastle upon Tyne Collection, Northumberland Museum & Archives, Woodhorn.

- Robert Carr Bosanquet: Excavations at Housesteads (= Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Newcastle upon Tyne. Number 8). 1898.

- RC Bosanquet: Excavations on the line of the Roman Wall in Northumberland. The Roman Camp at Housesteads. (= Archaeologia Aeliana: or miscellaneous tracts relating to antiquity. Number 25). 1904.

- Guy de la Bédoyère : Hadrian's Wall: history and guide. Tempus, 1998, ISBN 0-7524-1407-0 .

- Alan Rushworth: Housesteads Roman Fort - the Grandest Station: Excavation and survey at Housesteads, 1954-1995. 2 volumes. English Heritage, 2009, ISBN 978-1-84802-165-5 ( digitized from Volume 1 ).

- James Crow: Housesteads: A Fort and Garrison on Hadrian's Wall. 2., revised. Edition, Stroud 2004.

- James Crow: Housesteads Roman Fort. English Heritage (guidebook), 1989.

- James Crow, A. Rushworth: National Trust Archaeological Survey. Housesteads Roman fort and its environs: survey and analysis of the archaeological deposits. 1994.

- James Crow: English Heritage book of Housesteads. 1995.

- James Crow: Housesteads Roman Fort. 2012.

- Charles Daniels, John Gillam, James Crow, and others. a .: English Heritage Archaeological Report. 2 volumes. Swindon 2009.

- Roger Tomlin, RP Wright, M. Hassall: The Roman Inscriptions of Britain. Volume 3: Inscriptions on Stone 1955-2006. Oxford 2009.

- Robin George Collingwood, RP Wright: The Roman Inscriptions of Britain. Volume 1: Inscriptions on Stone. Oxford 1965.

- John Collingwood-Bruce: Handbook to the Roman Wall. 12th edition. Newcastle-upon-Tyne 1966.

- J. Collingwood Bruce, Charles Daniels: Handbook to the Roman Wall with the Cumbrian coast and outpost forts. 1981, pp. 138-155 and p. 334.

- CP Jones: Ten dedications “to the gods and goddesses” and the Antonine plague. In: Journal of Roman Archeology . Number 18, 2005.

- Eric Birley, Andrew Birley, J. Blake: The 1998 Excavations at Vindolanda: The Praetorium Site, Interim Report. Carvoran, 1999.

- Eric Birley: Housesteads Roman Fort, Northumberland. 2nd edition, H. M. S. O., London 1952.

- Eric Birley: Research on Hadrian's Wall. 1961, pp. 178-184.

- Eric Birley: Excavations at Housesteads in 1932 (= Archaeologia Aeliana: or miscellaneous tracts relating to antiquity. Number 10). 1933.

- Ronald Embleton, Frank Graham: Hadrian's Wall in the Days of the Romans. Newcastle 1984, pp. 130-151.

- Les Turnbull: Hadrian's Wall History Trails. Guidebook III, Newcastle 1974.

- MJT Lewis: Temples in Roman Britain. Cambridge 1966, p. 73, fig. 74.

- P. Beaumont: Society for the Promotion of Roman Studies Britannia. A journal of Romano-British and kindred studies. Number 39, 2008, pp. 59-84.

- P. McGowan, J. Crow, A. Rushworth, J. Renshaw: Housesteads Roman Fort: Conservation Plan. 2 volumes. 2002.

- Tony Wilmott: Hadrian's Wall: archaeological research by English Heritage 1976-2000. 2009, pp. 28-33.

- JA Biggins, DJA Taylor: A geophysical survey at Housesteads Roman Fort, April 2003 (= Archaeologia Aeliana: or miscellaneous tracts relating to antiquity. Number 33). 2004, pp. 51-60.

- Frank Graham: The Roman Wall. 1979.

- David Divine: The North East Frontier of Rome. 1969.

- English Heritage: Booklet Guide to Housesteads Roman Fort, new edition. 2008.

- Glen Lyndon Dodds: Historic Sites of Northumberland & Newcastle upon Tyne. 2002, pp. 96-103.

- Stephen Johnson: Hadrian's Wall. English Heritage, BT Batsford, London 2004, ISBN 0-7134-8840-9 .

- George Fraser MacDonald: The Steel Bonnets . Harper-Collins, 1971.

- Keith Durham: The Border Reivers . Osprey Publishing, 1995.

Remarks

- RIB = Roman inscriptions in Britain

- ^ RIB 1594

- ↑ Emil Hübner : Borcovicium . In: Paulys Realencyclopadie der classischen Antiquity Science (RE). Volume III, 1, Stuttgart 1897, Col. 720.

- ^ Alan Rushworth, 2009, p. 329; Frank Graham, 1979, p. 101.

- ↑ Guy de la Bedoyere, 1998, p. 74.

- ^ Alan Rushworth (2009), p. IX

- ^ J. Collingwood-Bruce, 1966, p. 112.

- ↑ Guy de la Bedoyere, 1998, p. 74, Alan Rushworth, 2009, p. XVIII.

- ↑ See also the article: RW Davies, The Roman Military Diet . Britannia II, 1971, pp. 122-142, A. Rushworth English Heritage, 2009.

- ^ Alan Rushworth, 2009, XVIII

- ↑ Frank Graham, 1979, p. 99.

- ↑ Alan Rusworth, 2009 S. XVII

- ↑ Rushworth / Daniels / Gillam / Crow 2009, pp. 35–36.

- ↑ Guy de la Bedoyere, 1998, p. 78, John Collingwood-Bruce, 1966, p. 116.

- ^ J. Collingwood-Bruce, 1966, p. 120.

- ↑ Guy de a Bedoyere, 1998, pp. 76-77, J. Collingwood-Bruce, 1966, p. 117.

- ^ A b Alan Rushworth, 2009, p. XVII

- ↑ Guy de la Bedoyere, 1998, pp. 78-79, J. Collingwood-Bruce, 1966, p. 112.

- ↑ Guy de la Bedoyere, 1998, pp. 79-80.

- ^ RIB 1618 , Guy de la Bedoyere, 1998, p. 79, medicus ordinaris referred to an officer in the knightly rank or his salary group.

- ↑ Stephen Johnson, 2004, p. 46, J. Collingwood-Bruce, 1966, p. 116.

- ^ Margot Klee, 2006, p. 21.

- ↑ Guy de la Bedoyere, 1998, pp. 75-76.

- ↑ J. Collingwood-Bruce, 1966, p. 16.

- ↑ RIB 1582 , RIB 1583 , RIB 1577

- ↑ RIB 1593 , RIB 1594, RIB 882 , 241 AD, RIB 1036 ; undated

- ^ RIB 1576 , J. Collingwood-Bruce, 1966, p. 111.

- ↑ RIB 1618 ; RIB 1619 ; RIB 1580 , RIB 1586 , ND Occ. XL

- Jump up ↑ RIB 1572, RIB 1646, Guy de la Bedoyere, 1998, p. 78.

- ↑ James Crow 1995 and 1989, pp. 34-36.

- ^ Nick Hodgson 2009, pp. 112–114, James Crow 1995, pp. 67–73, Rushworth / Daniels / Gillam / Crow 2009, fig. 10.20 and 10.22 (diagnosis plan and photographs), Guy de la Bedoyere, 1998, pp. 74–75.

- ↑ E. Birley 1933, pp. 82-96. J. Hodgson 1822, pp. 263-320, RC Bosanquet 1904, pp. 193-299, J. G. Crow, A. Rushworth 1994, p. 49.

- ↑ RIB 1578 , RIB 1580 , Archaeologia Aeliana: or miscellaneous tracts relating to antiquity, therein: E. Birley, GS Keeney: Fourth Report on Excavations at Housesteads. 12, 1935, pp. 230-234.

- ^ RIB 1576 , 1593 , 1594 , John Collingwood-Bruce, 1966, p. 124.

- ^ RC Bosanquet: The roman castle in Housesteads, Archaeol. Ael., 2 XXV, 1904, pp. 255 ff., Thomas Hodgson: Report in the Newcastle Chronicle of October 26, 1822 (quoted by JC Bruce, 93); J. Hodgson in Archaeologia Aeliania 1.1822, p. 263 ff .; History of Northumberland, II (3) 1,190; Lauchlan, Roman wall, sheet III; Bruce, Lep. September, p. 96 f .; MMM II p. 393 ff., No. 273, see Fig. 312; RC Bosanquet in Arch. Ael. XXV, 1904, pp. 257 ff., Fig. 224, J. Collingwood-Bruce, 1966, pp. 122-124.

- ↑ RIB 1579 and RIB 1598

- ↑ James Crow, 1995, pp. 95-98, Alan Rushworth, 2009, pp. 321-322, RC Bosanquet 1904, p. 242.

Web links

- RIB Roman Inscriptions of Britain inscription database

- English Heritage website

- Hadrian's Wall photo album on Flickr

- Aerial view of the excavations on Flickr

- Hadrian's Wall photo album on Flickr

- Satellite photo of the fort area, location of Roman monuments on Vici.org.

- Vercovicium on Roman Britain

- Reconstruction model of Housesteads Fort (2nd century AD)

- Housesteads Fort on PASTSCAPE

- Part VII on You Tube, The Wall from Arbeia to Maia. Film production with 3D-CGI models, images and explanation of the individual Roman castles along Hadrian's Wall (English).

- Odyssey of Archeology The Wall

- English Heritage Archaeological Monographs

- Medicine in the Roman military

- Housesteads bibliography on English Heritage

- John Collingwood Bruce: The Roman Wall: A Description of the Mural Barrier of the North of England, 1867, with numerous pictures of wall remains, altars, inscriptions etc.