Notitia dignitatum

The Notitia dignitatum is a late Roman state handbook , which in its current text form was probably created between 425 and 433. However, it can be assumed that the records go back to the year 395 or use even older sources . The text provides an overview of the administrative structure of the late ancient Roman Empire , the military and civil services and the distribution of the units of the army in the western and eastern halves of the empire. It is passed down through medieval manuscripts. However, the Notitia contains a great deal of verifiably outdated or inaccurate information and is classified as a highly problematic source in research.

Lore history

The Notitia dignitatum was handed down to the library of the Speyer cathedral monastery in only one manuscript . This so-called Codex Spirensis from the 9th or 10th century was an anthology with copies of around a dozen ancient and two early medieval works on geography, transport and administrative history. Several of them contained miniatures that were based on illustrations from late antiquity. The two most extensive works were:

- the Notitia dignitatum , and

- the Itinerarium Antonini , a street directory from the time of Emperor Caracalla .

The Codex Spirensis was first discovered by Italian humanists during the Council of Basel (1431–1437), but was then forgotten again until Beatus Rhenanus found it again around 1525 in the Speyer cathedral library. It was finally lost around 1672, but four copies have been preserved, these are now in:

- Oxford ( Bodleian Library , Ms. Canon. Misc. Lat. 378), written around 1440;

- Paris ( Bibliothèque nationale de France , lat. 9661), originated around the same time;

- Trient (Biblioteca Comunale, W 3103), created around 1484 (without images) and

- Munich ( Bayerische Staatsbibliothek , Clm 10291), made around 1542 for Count Palatine Ottheinrich .

The authoritative edition of the Notitia dignitatum was published by Otto Seeck in 1876 .

designation

The name is derived from the beginning of the text of the document: Notitia dignitatum continet omnium tam civilium quam militarium dignitatum utriusque imperii occidentis orientisque ("Record of the dignitaries, includes all dignitaries, both civil and military, of the western and eastern empires") .

The multi-part structure of the late Roman army was also reflected in the standard names. Some of the classic legions continued to use their nicknames, but there were also - mostly under the tetrarchs Diocletian and Maximian - newly established legions. Some of them were after

- ancient Roman gods ( Herculii, Martii, Solenses, Dianenses, Minervii ),

- Imperial dynasties ( Constantiani, Jovii, Valentiniani, Theodosiani ),

- Germanic or Asian tribal formations ( Alamanni, Batavi, Franci; Brisigavi, Persae, Transtigrani ),

- Ethnic groups ( Gentiles, Alpini ),

- Equipment ( Lancearii, Sagittarii, Funditores, Balistari, Clibanari, Cornutti, Cetrati, Scutari, Tubantes, Dromedarii ), or

- Special forces or their properties ( Exploratores, Defensores, Victores, Vindices, Tonantes, Feroces, Muscularit Leones ).

Origin and intended purpose

The origins and purpose of the Notitia dignitatum are controversial in research . There is largely only agreement that its eastern section in the version that still exists today was created between the years 394–396 (around the time of the death of Emperor Theodosius I ). The eastern Notitia then probably served as a model for the writing of its western part. The later additions for the western half of the empire date back to between 420 and 430, although these are not uniform and complete. Apparently an attempt was made to update the Western Notitia in this way, but it was apparently only partially successful. The troop list West therefore reflects different states of the army, as they were at different times at the end of the 4th and beginning of the 5th century, after the military reforms of Diocletian (285-305) and Constantine I (306-337). could have passed. However, this document (the earliest fully illustrated copy of the lost original data dates from 1542) is incomplete and in places very difficult to interpret. The version copied in the Middle Ages probably originally came from West Rome, as the eastern half has obviously not been revised. There is evidence that garrison units and camps are still listed in the Notitia, which no longer existed at the turn of the century. On the other hand, forts that were still manned by regular troops in the late 4th century were not listed. Some of the place names could not be proven archaeologically.

The notitia was kept and kept by the primicerius notariorum , the first notary in the empire. One of its tasks was to issue certificates of appointment for the highest civil servants and the military ( codicilli ). When changes were made to the bureaucratic and military structures in the Reich, he made the necessary corrections. After Honorius' death in August 423, in the autumn of the same year, with the help of Flavius Aëtius, a certain Johannes became the new emperor in the west for a few months . Johannes, as the only one of the emperors before and after him, had previously held the office of primicerius notariorum, i.e. that which u. a. was also responsible for the lists of troops and letters of appointment of the military commanders. The Notitia dignitatum would go well with this official on the imperial throne . So the assumption remains that in the version last updated (for the West) it was supposed to serve as a gift for Johannes on the occasion of his accession to the throne on November 20, 423, but this thesis, mainly represented by Ralf Scharf, is controversial in research and ultimately hardly to prove. Since the Notitia dignitatum in its present form is a document of the unity of East and West Rome, there is also a connection with the installation of Emperor Valentinian III. (425 to 455) by the Eastern Emperor Theodosius II , since under these two blood-related rulers the togetherness of both halves of the empire came to the fore again. In 1992 Gianfranco Purpura proposed that the Notitia dignitatum should be viewed as a gift from Theodosius II to his young cousin and emperor colleague on his 10th birthday; and in 1996 Peter Brennan even said that he had identified the Praetorian prefect Macrobius Ambrosius Theodosius as the author.

Composition and content

The work consists of the notitiae dignitatum tam civilium quam militarium in partibus orientis and occidentis , i.e. two lists of all civil and military dignities of the western and eastern Roman part of the empire. These two sub-documents can be viewed as a kind of administrative reference work in the modern sense, which gives the reader an insight into the organization and hierarchy of the civil and military departments. In the individual chapters the titles of the civil servant, his area of responsibility, his administrative staff and, in the case of the military, also the units and locations are named. The list is based on the rank of the respective office within the court society and according to a geographical principle.

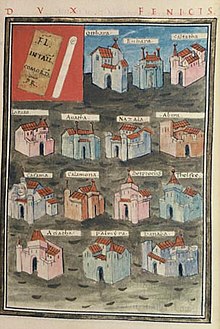

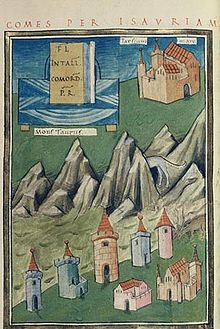

The Notitia is richly illustrated and shows, among other things, the shield patterns of the individual military units as well as stylized views of cities and forts. The four well-known and preserved medieval copies also reproduce the richly colored illustrations, which probably largely correspond to those of the original, but due to misunderstandings they also contain some errors and anachronisms. As a source for late antiquity , the text is of great value, even if many details are still controversial - among other things, the fact that Britain is still listed is an indication that the Romans also want the island after it has been withdrawn the field army and high officials, around the year 410, still considered part of the empire.

Chapter structure

The Notitia dignitatum comprises 90 chapters, each with a picture panel and between five and twenty objects depicted in them per picture panel. In addition, there are around 3600 lines of text listing offices and military units. On the boards of the border troop commanders ( Dux / Comes ) the upper left corner is u. a. reserved for specifying their title comes primi ordinis . The text given in abbreviations is:

"[ Fl ] oreas [ int ] er [ ali ] os [ com ] ites [ ord ] inis [ pr ] imi " - "May you flourish among the first-rate followers."

This text is inside a white board, which is shown in some illustrations as a book-like insignia. Such text fields can only be found in the chapters of the viri spectabiles , those incumbents who belonged to the middle senatorial class from 364 onwards. They are always combined with a scroll that serves as a symbol of the imperial letter of appointment that was given to the incumbent on the occasion of his installation ceremony. The panels also contain the garrison type of the troops of the respective dux , which are indicated by strongly stylized depictions of cities and fortresses, under which the associated place name is. The thirteen hexagonal vignettes in the illustration of Dux Foenicis as symbols for the garrisons he controls, however, only reproduce a standardized type of image of a fort or a fortified city. The different number of towers and gates as well as the changing colors should probably create a certain variety. It was not intended to reproduce a specific fort or a certain level of importance here.

The chapter text always begins with the formula:

" Sub dispositione viri spectabilis " - "At the disposal of the highly regarded dux / comes from ...".

The structure of the lists of troops corresponds to the usual notitia scheme : First the rank of the commanding officer is stated, then the name of his unit and finally its garrison location. The officers of the administrative staff are listed after the troops.

Definition of the figures

The various illustrators of the manuscript tried to reproduce the late Roman insignia as precisely as possible, as the comparison with ancient illustrations shows, but they obviously allowed themselves some freedom in the representation of decorative details such as clothing; in addition, they probably misinterpreted some of the late Roman abbreviations. The insignia of the high officials are represented as an ensemble of codicilli - gold-trimmed certificates of appointment in ivory frames with the imperial portrait - or as a book with heraldic painting on the book cover together with scrolls. The codicil - and sometimes the books - are arranged on a table with a patterned cover. In some cases there is also a carved ivory column on a tripod. It represents the ceremonial writing utensils and is supposed to symbolize the judicial power.

Each late Roman military unit had its own shield; some of them were handed down in the Notitia, there are predominantly circular color divisions, but there are also rune-like symbols and early forms of heraldic emblems such as dragon, snake, wolf, lion, eagle, bull, raven, two-headed ( zoomorphic ) motifs, sun, stars , Flower, cross, wheel, wreaths, victorias , people, heads and twin representations (presumably images of emperors). In the Notitia there are also several variants of a shield pattern that look amazingly similar to the Far Eastern Yin and Yang symbol. Presumably they go back to a Celtic symbol, see u. a. on the so-called Desborough mirror, a bronze mirror made between 50 BC and 50 AD, found in 1908 in Northamptonshire, England. Such spiral symbols are a common part of early Celtic art, especially in the British Isles.

Army lists

For the mobile field armies ( comitatenses ) two lists were created in the Notitia dignitatum . The first counts the respective regiments ( numeri ) and their highest commanders , den

- Magister peditum ( infantry ) and the

- Magister equitum ( cavalry ),

both stationed in the western empire. In the second ( distributio numerorum ) their stationing locations and section commanders are noted. Another big problem is the almost complete lack of information on the number of troops, so that an exact estimate of the size of the army at that time is impossible and therefore only halfway accurate information can be given for the late 4th century. The problems with the evaluation of the administrative and military organization of the border provinces in the Alps-Danube region have not yet been satisfactorily resolved. More recent research has revealed that the information about the field armies of the western empire ( palatini and comitatenses ) probably come close to the target for the years between 420 and 425, but that the records relating to the eastern army no longer corresponded to the reality from the year 395 onwards . Only the list of the Ostillyrian Army Group was updated again between 396 and 410. The lists of the border troops ( limitanei ) on the Danube also have different and often contradicting entries. It is also questionable whether the lists of the Norico-Pannonian limitanei extend beyond the years 375–378. The associations listed in the Notitia would result in a nominal strength of 524,000 to 600,000 men. For the 6th century, Agathias mentions a target of 645,000 soldiers, but the nominal strength of the western army - which had long since been disbanded at the time - was taken into account. In fact, he writes, only 150,000 men served in the east.

The evaluation of the above lists suggests that the Western Roman army suffered the most losses after the disaster of 406 . Almost half of its units are likely to have been worn out or broken up in the clashes of the early 5th century. In 395 the eastern field army comprised 157 units, the western - up to 420 - even 181 units. Of these, 97 had been set up in the late 4th century and only 84 of them were from the years before 395. The newly formed units of the western army were, however, 64 percent withdrawn from the limitanei . Many of their regiments appear (in the sections of the lists that were no longer corrected afterwards) in their old stations on the limes . The losses of the Western Army had not been compensated for with newly recruited soldiers, but merely by changing the status of existing units. About a third of the 35 new units of the field army were recruited from Germanic tribes (e.g. Attecoti, Marcomanni, Brisigavi ). If one believes the figures in the final version of the Notitia dignitatum , the western field army was even stronger at this point than 25 years earlier. While the field army was now apparently larger, the number of soldiers in the western army had actually shrunk considerably, as most of the limitanei upgraded to comitatenses could no longer be replaced by new units due to lack of money. This was particularly true of the border troops in Gaul . Overall, the number of units of “real comitatenses ” is even likely to have fallen by 25 percent in real terms (ie from approx. 160 to 120 units).

Another mystery is the province of Germania II , as it is not mentioned in the Notitia at all. Neither with their own list of troops nor by specifying a dux . It therefore remains unclear how - or in which units - the border troops there were organized in the 4th and earlier 5th centuries. Various answers have been found in the relevant research: Either the corresponding copy of the Western Notitia has been lost in the course of time; or the defense of the forts on the Lower Rhine had been largely in the hands of Germanic mercenaries or federates, who - as they were viewed as irregular - were no longer included in the troop lists since the early 5th century. It is also possible that the bank of the Rhine was only monitored by comitatensis or pseudo- comitatensic units at that time . Archeology has also provided some new insights into this in recent years (findings from Rhine fort sites). According to this, the Roman border protection in Germania II , however it may have been set up, was likely to have existed well into the 5th century.

Administrative staff

In their management tasks, Comites and Duces were supported by an extensive administrative staff. In the Notitia their administrative staff ( officiales ) were given for 38 military commanders . The army masters also exercised their control of the comites and duces , especially through their offices ( officium ). Theodor Mommsen was able to prove that the appointment of the law firm's board members was handled differently. Since the introduction of a new chancellery order in 395, the majority of them have been used by the army masters every year. The officials sent directly to the administrative staff by the army master's office were always higher in rank than those recruited by the border commanders. By appointing officials there who were devoted to him and who were also jointly liable for the actions of their superiors, he was able to monitor his officers better and enforce uniform standards in military policy. In the Pannonian provinces, however, they were still elected autonomously from within their own ranks. It is noticeable that the office of the cornicularis appears in only six administrative staffs. The reason for this is probably that this functionary was probably responsible for the replenishment of his unit. In the late Roman administration this task fell to the civil administration of the province.

In the Notitia the following posts are given for the officium :

- princeps officii (board of directors)

- numerarius (treasurer / paymaster)

- commentariensis (bookkeeper and legal expert)

- cornicularis (secretary and steward)

- adiutorem (assistant)

- regrendarium (administrator)

- exceptores (lawyers)

- singulares et reliquos officiales (bodyguards and other officials)

- subadiuuam (assistant)

The late antique administrative and military organization

The organizational structure in civil and military administration, as described in the Notitia dignitatum , is essentially based on the reforms of Diocletian and Constantine and the division of the empire by Valentinian I and Valens into Occident (west) and Orient (east) in the late 4th century. Under Diocletian the number of provinces almost doubled. Up to 114 provinces have survived. These in turn were grouped together in dioceses . While there were initially only 12 of these middle administrative units, under Emperor Theodosius I there were already 14. Since the four-emperor rule (tetrarchy) over a correspondingly subdivided empire was only a short episode, the formation of large administrative units in the long run. The creation of the territorial Praetorian prefectures (under Constantine four, between 337 and 395 only three, then again four), which took on this task, was initiated by Constantine I.

The Diocletian-Constantinian reform activities dealt primarily with the army. The entire executive was reorganized, whereby - contrary to the previous Roman practice - a separation between civil and military power was introduced. The main reason for this measure can be found in the renewed division of the provinces: If civil and military offices had been left in one hand, a division of the areas of command would have become inevitable. But that would often not have made strategic sense. Most of the newly created provinces were too small to be able to set up and maintain sufficiently large units. It lost more and more of its importance as a military force because the new field armies had to operate supraregional. Therefore, in several cases it was necessary to place the armed forces of several provinces under the command of a military leader (e.g. the Dux Pannoniae Primae et Norici Ripensis ). Another reason lies in the increase in administrative tasks, the administration of which only became necessary through the reforms of Diocletian and for this purpose required officials - including those with professional expertise. However, the separation may not have been fully implemented at the time of Diocletian, as one can read in the sources of praesides who continued to exercise civil and military offices in personal union. These reforms were only finally completed under Constantine I.

In the centuries that followed, the civil bureaucracy was considered to be militia Romana , which was now only open to citizens with legal training, but the army, militia armata , was opened to the "lower people" and "barbarians" to a far greater extent than before. Those units of the army that continued to serve on the border, the limes , were in their sections under the command of a Dux Limitis , and are first mentioned in the sources in 363 as Limitanei . Although the border army had a lower status, it did not differ significantly from the comitatus , the mobile marching or field army under the command of a Comes rei militaris, referred to as the imperial allegiance. According to Notitia, the prefects were in command of the legions, as well as the milites and classis units, while the tribuni were at the head of the cohort formations.

In addition to the members of the guard ( scholars ), the “palace people”, palatini , were among the emperor's closest entourage. They were initially provided by the elite legions or auxiliary associations recruited from particularly reliable barbarian tribes. The second group in the movement army were the actual followers, the Comitatenses , in which the most powerful delegations ( vexillations ) of the other legions were placed. The lowest rank in the mobile field army was ultimately taken by the pseudocomitatenses , who were temporarily withdrawn from the border troops if necessary.

| Administrative level | Military commander |

Civil administrator |

|---|---|---|

| province | Comes / Dux limitis | Proconsul / Consulares / Corrector / Praesides |

| diocese |

Magister militum (Eastern Empire) / Comes rei militaris (Western Empire) |

Vicarius |

| Praetorian Prefect | Augustus / Caesar | Praefectus praetorio |

Civil and military offices listed in the Notitia

Eastern Empire

Civil administration:

The highest civil officials in the Orient were:

- 2 Praefectus Praetorio (Orientis, Illyrici),

- 1 Praefectus urbis Constantinopolitanae (city and vicinity of Constantinople),

The Praefectus praetorio Orientis are subordinate to 5 vicars :

- Asiana,

- Pontica,

- Thracia,

- Aegyptus and

- Oriens.

The provinces of these 5 dioceses are administered by 1 Proconsul , 12 Consulares, 1 Corrector and 32 Praesides .

Two vicars are subordinate to the Praefectus praetorio Illyrici :

- Dacia and

- Macedonia.

The provinces of these 2 dioceses are administered by 1 Proconsul, 3 Consulares, 1 Corrector and 8 Praesides.

Military Administration:

The highest military posts in the east were those of the

- Magister militum praesentalis I,

- Magister militum praesentalis II,

- Magister militum per Orientem,

- Magister militum per Thracias and the

- Magister militum per Illyricum.

In Egypt and North Africa, the following are subordinate to the Magister militum praesentalis I:

The Magister militum praesentalis II controls the in Pontus (Black Sea coast, Armenia)

- Dux Armeniae,

- Comes per Isauriam.

In the Middle East, the following are subordinate to the Magister militum per Orientem:

- Dux Foenicis,

- Dux Syriae,

- Dux Palestinae,

- Dux Osrhoenae,

- Dux Mesopotamiae,

- Dux Arabiae.

Subordinate to the Magister militum per Thracias on the lower Danube are:

The following are subordinate to the Magister militum per Illyricum in the Balkans :

Western empire

Civil administration: The highest civil officials in the Occident were:

- 2 Praefectus Praetorio (Italy, Gaul),

- 1 Praefectus urbis Romae (city and region of Rome).

3 vicars are subordinate to the Praefectus praetorio Italiae:

- Illyricum,

- Italiae,

- Africae.

3 vicars are subordinate to the Praefectus praetorio Galliarum:

- Septem Provinciarum,

- Hispaniarum,

- Britanniarum.

Military Administration: The highest military offices in the West were those of:

- Magister peditum in praesenti,

- Magister equitum in praesenti (these two offices were later combined in the Magister militum praesentalis).

The following are subject to the Magister militum for Italy, Slovenia and the Eastern Alps:

for the western Illyricum (Balkans, upper and middle Danube border) of:

- Comes Illyrici ,

- Dux Pannoniae secundae ripariensis et Saviae ,

- Dux Valeriae ripensis ,

- Dux Pannoniae Primae et Norici Ripensis ,

for Hispaniarum (Spain, Portugal): a

for Tingitaniam (western Algeria, Morocco): a

for intra Africam (Tunisia, Algeria, Libya)

- Comes Africae ,

- Dux et praeses provinciae Mauritaniae et Caesariensis ,

- Dux provinciae Tripolitanae ,

for Britain (England, Hadrian's Wall , Wales and Saxon Coast, British part):

for Gaul, the Saxon coast (Gaulish part), the western Alps and the Rhine border of:

- Magister equitum per Galliarum,

- Comes tractus Argentoratensis ,

- Dux Belgicae secundae ,

- Dux Germaniae primae ,

- Dux Mogontiacensis ,

- Dux provinciae Sequanicae ,

- Dux tractus Armoricani et Nervicani .

Units of the western and eastern Roman armies listed in the Notitia Dignitatum

| units | West (booth 410-420) | East (booth 395) | total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Schola | 5 | 7th | 11 |

| Vexillatio palatina | 14th | 10 | 20th |

| Vexillatio comitatensis | 28 | 30th | 58 |

| Vexillatio equitum / Equites | 71 | 50 | 121 |

| Ala | 72 | 10 | 82 |

| Cuneus equitum | 33 | 14th | 47 |

| total | 225 | 121 | 339 |

|

Commanding Officer |

Garrison or headquarters |

Surname |

Number of units |

Team strength (highest level) |

| Comes domesticorum equitum | Constantinople | Schola scutariorum clibanariorum * | 1 | 500 |

| Magister militum praesentialis I. | Nicea |

Comites clibanarii * Equites cataphractarii Biturigenses Equites I clibanarii Parthi |

3 | 1500 |

| Magister militum praesentialis II | Adrianople |

Equites Persae clibanarii * Equites cataphractarii Equites cataphractarii Ambianenses Equites II clibanarii Parthi |

4th | 2000 |

| Magister militum per Orientem | Antioch (Syria) |

Comites cataphractarii Bucellarii iuniores Equites promoti clibanarii Equites IV clibanarii Parthi Cuneus equitum II clibanariorum Palmirenorum |

4th | 1750 |

| Magister militum per Thracias | Marcianopel | Equites cataphractarii Albigenses | 1 | 500 |

| Dux Thebaidos | Pambane | Ala I Iovia cataphractariorum | 1 | 250 |

| Dux Scythiae | Arubio | Cuneus equitum cataphractariorum | 1 | 250 |

| Eastern Empire as a whole | 15th | 6750 | ||

| Magister equitum praesentalis | Mediolanum |

Comites Alani * Equites sagittarii clibanarii |

2 | 1000 |

| Comes Africae | Carthage | Equites (sagittarii) clibanarii | 1 | 500 |

| Comes Britanniarum | Londinium | Equites cataphractarii iuniores | 1 | 500 |

| Western empire as a whole | 4th | 2000 | ||

| Guard units are marked with *. | ||||

Auxilia palatina

|

|

|

expenditure

- Otto Seeck : Notitia dignitatum. Accedunt notitia urbis Constantinopolitanae et laterculi provinciarum. Weidmann, Berlin 1876 ( digitized ; reprinting unchanged. Minerva, Frankfurt am Main 1962).

- Concepción Neira Faleira: La Notitia dignitatum. Nueva edición crítica y comentario histórico (= Nueva Roma 25). Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas, Madrid 2005, ISBN 84-00-08415-2 .

literature

Overview representations in manuals

- Klaus-Peter Johne: Notitia dignitatum. In: The New Pauly (DNP). Volume 8, Metzler, Stuttgart 2000, ISBN 3-476-01478-9 , Sp. 1011-1013.

- Daniëlle Slootjes: Notitia dignitatum. In: Real Lexicon for Antiquity and Christianity . Volume 25, Hiersemann, Stuttgart 2013, ISBN 978-3-7772-1318-7 , Sp. 1133-1145

- Matthias Springer : Notitia dignitatum. In: Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde (RGA). 2nd Edition. Volume 21, Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2002, ISBN 3-11-017272-0 , pp. 430-432.

Investigations

- Pamela C. Berger: The insignia of the Notitia dignitatum. Garland, New York 1981, ISBN 0-8240-3927-0 .

- Peter Brennan: The Notitia Dignitatum. In: Entretiens Fondation Hardt 42, 1996, pp. 147-178.

- Roger Goodburn, P. Bartholomew (Ed.): Aspects of the notitia dignitatum. Papers presented to the conference in Oxford, December 13 to 15, 1974 (= British archaeological reports Supplementary series 15). Oxford 1976.

- Dietrich Hoffmann : The late Roman movement army and the Notitia Dignitatum (= epigraphic studies. Vol. 7). 2 volumes. Rheinland-Verlag, Düsseldorf 1969-1970, ISSN 0071-0989

- Michael Kulikowski: The Notitia Dignitatum as a historical source. In: Historia . Vol. 49, 2000, pp. 358-377.

- Gianfranco Purpura: Sulle origini della Notitia Dignitatum. In: Atti del X Convegno Internazionale Accademia Costantiniana di Perugia, 8 ottobre 1991. Perugia 1995, pp. 347–357 (= Annali dell'Università di Palermo 42, 1992, pp. 471–483; digitized version (no longer available online. ) Archived from the original on August 22, 2006 ; accessed on 10 March 2018 . )

- Ralf Scharf: The Dux Mogontiacensis and the Notitia Dignitatum. A study on the late antique border defense (= Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde. Supplementary volume 48). de Gruyter, Berlin a. a. 2005, ISBN 3-11-018835-X .

- Jürgen Oldenstein: Alzey Castle. Archaeological investigations in the late Roman camp and studies on border defense in the Mainz ducat . 2009 ( hbz-nrw.de [PDF; 14.9 MB ] Habilitation thesis University Mainz 1992).

- Konrad Stauner: The cornicularius in the offices of the comital and ducal commanders in the Notitia dignitatum. In: Tyche. Contributions to ancient history, papyrology and epigraphy . Volume 25, 2010, pp. 131-171 ( online ).

- Pat Southern: The Roman army, a social and institutional history. Santa Barbara, California 2006, ISBN 1-85109-730-9 .

- Karl Heinz Dietz, Udo Osterhaus: Regensburg in Roman times. Verlag Friedrich Pustet, Regensburg 1979. ISBN 3-7917-0599-7 .

Web links

- Bayerische Staatsbibliothek : Notitia Dignitatum Clm 10291 - full online version (collective manuscript: the link refers to the first page of the Notitia dignitatum )

- lat. full text

- Compilation description and references

- English translation

- Color illustrations of the shield signs in the Notitia dignitatum

- Notitia dignitatum in the Bibliotheca Augustana

- Notitia Index

- PDF assignment of the units specified in the ND, according to Ingo Maier

Remarks

- ^ Notitia Oriens Title I: List of duces .

- ↑ AHM Jones 1964, p. 610.

- ↑ Dietz 1979, p. 127

- ↑ Pat Southern 2006, p. 255.

- ↑ Peter Heather: The fall of the Roman Empire . 2nd Edition. Rowohlt, Reinbek 2011, ISBN 978-3-499-62665-4 , p. 289.

- ↑ The western Roman infantry units armigeri defensores seniores ("shield bearer") and Mauri Osismiaci had a coat of arms on their shields that corresponded to the dynamic, right-hand variant of the Far Eastern tradition. Another legionary unit, the Thebaei , had a shield pattern comparable to the static variant of East Asian Taijitu . These Roman symbols precede the later Daoist versions by nearly seven centuries. See also: Giovanni Monastra: The “Yin-Yang” among the Insignia of the Roman Empire? , Sophia , Vol. 6, No. 2 (2000). Isabelle Robinet: Taiji do. Diagram of the Great Ultimate , in: Fabrizio Pregadio (Ed.): The Encyclopedia of Taoism A – Z , Routledge, Abingdon (Oxfordshire) 2008, ISBN 978-0-7007-1200-7 , pp. 934-936 (934) . Late Roman Shield Patterns. Notitia Dignitatum: Magister Peditum . Helmut Nickel: The Dragon and the Pearl. In: Metropolitan Museum Journal 26, 1991, p. 146 footnote 5.

- ↑ Notitia Dignitatum Occ. V, VI and VII.

- ^ Dietrich Hoffmann: Movement Army ; Karlheinz Dietz: Cohortes, ripae, pedaturae. On the development of the border legions in late antiquity . In: Festschrift Adolf Lippold , 1993, pp. 279–329 (with detailed references) full text .

- ↑ Peter Heather: The fall of the Roman Empire . 2nd Edition. Rowohlt, Reinbek 2011, ISBN 978-3-499-62665-4 , p. 289.

- ↑ Peter Heather: The fall of the Roman Empire . 2nd Edition. Rowohlt, Reinbek 2011, ISBN 978-3-499-62665-4 , p. 289.

- ↑ Peter Heather: The fall of the Roman Empire . 2nd Edition. Rowohlt, Reinbek 2011, ISBN 978-3-499-62665-4 , pp. 290–291, Michaela Konrad , Christian Witschel (organizer): Conference report on the international colloquium “Roman legionary camps in the Rhine and Danube provinces - nuclei late antique and early medieval Life? ” Bavarian Academy of Sciences, Munich from March 28 to 30, 2006, pp. 11–13. PDF (353 kB) .

- ↑ Friedrich Anders 2010, pp. 123–124, Jürgen Oldenstein, 2009, pp. 291–292, Konrad Stauner, pp. 138 and 141.

- ^ Karen Piepenbrink : Konstantin der Große und seine Zeit , Geschichte Kompakt series, 2nd edition, Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, Darmstadt 2007, ISBN 978-3-534-20905-7 , p. 15.