Vindolanda

| Chesterholm Castle | |

|---|---|

| Alternative name | Vindolanda / Vindolana / Vindolande |

| limes | Britain |

| section |

Stanegate Hadrian's Wall (rear) |

| Dating (occupancy) |

a) Flavian, at the earliest around 80 AD to 97 AD. b) Nervous / Trajanic, 97 AD |

| Type | Equestrian and cohort fort |

| unit |

a / b / c) Cohors I Tungrorum milliaria a / b) Cohors IX Batavorum milliaria equitata |

| size |

H / E phase I: 1.4 ha, H / E phase III: 2.8 ha, H / E phase IV: 3.2 ha, stone phase IX: 1.4 ha |

| Construction |

a / b / c) wood-earth, d / e) stone |

| State of preservation | Square system with rounded corners, foundations of the stone fort and the vicus partially restored and preserved |

| place | Bardon Mill |

| Geographical location | 54 ° 59 '28.8 " N , 2 ° 21' 37" W |

| height | 165 m ASL |

| Previous | Newbrough forts (east) |

| Subsequently | Haltwhistle Burn small fort (west) |

| Upstream | Housesteads Fort (Hadrian's Wall) (northeast) |

| Diorama of the fort (3rd century) |

|---|

| Tina Madsen , 2014 |

| Vindolanda Museum Chesterholm

Link to the picture |

Vindolanda was a Roman auxiliary forces fort , near the village of Bardon Mill / Henshaw, district Chesterholm, County Northumberland , England.

The Romans advanced in the 1st century AD to what is now the border area between England and Scotland. This is where most of the troops were concentrated at the time of their rule over Britain. The securing of the border through a dense chain of forts such as Vindolanda and military roads such as the still visible so-called Stanegate began in the late 1st century after the Romans had given up part of their conquests in Scotland. The permanent presence of Roman soldiers since the early Trajan times could be unequivocally attested by archeology. The border region, which stretched across northern England from the mouth of the Tyne to the Solway Firth , was accessed by a well-developed military road known as Stanegate since the Middle Ages. It marked the first solid borderline in Roman Britain. The fort crew of Vindolanda was initially responsible for security and surveillance tasks at the border and later for the control of the hinterland of Hadrian's Wall . Located on the very edge of one of Rome's most remote provinces, the people of Vindolanda were heavily dependent on the use of local resources and their ingenuity. Today it is known that in Chesterholm there are the remains of nine successive Roman castles. Due to the practice at the time of leveling the area or covering it with a new layer of clay before starting a new building, thousands of ancient artifacts have been remarkably well preserved. The excavation site became popular across the region, primarily due to the numerous fragments of ancient writing boards that were recovered there. Outside the fortress there was a larger civil settlement with bath houses, temples and an adjoining burial ground. Vindolanda is one of the best-researched archaeological monuments in the United Kingdom because of its long occupation, the partially very well-preserved wall structure and the spectacular archaeological finds . Today you can see the large-scale excavated, late antique stone fort and the civil settlement, as well as a museum with a selected collection of finds and several building reconstructions on the exhibition grounds.

This article contains the description of the fort, civil settlement and the two watchtowers in neighboring Barcombe .

Surname

In 1914, while looking for a well, a worker found a sandstone altar 110 meters west of the fort, which had been dedicated to the ruling imperial family and the god Vulcanus by the former residents of the civil settlement ( vicani ) . Its inscription revealed the ancient name of the settlement. The altar probably dates from the years between 223 and 225. The place name also appears in one of the Vindolanda tablets . It can be derived from the Celtic . Vindo means white , but it can also be a person or field name. The probably Latinized form Vindolanda could thus be resolved as a white fortress, a white shimmering meadow or the house or courtyard of Vindo. The location is also mentioned in the two most important late antique written sources. In the Notitia Dignitatum (late 4th and early 5th centuries) it appears as Vindolana between Borcovicio (Housesteads) and Aesica (Great Chesters). In the cosmography of the geographer of Ravenna (7th century) it is found as Vindolanda , where it is mentioned between the entries for Camboglanna (Castlesteads) and Longovicium (Lanchester). It is referred to as "Chesters on Caudley", "Little Chesters" and "The Bower" in the records of the antiquarians who visited Chesterholm.

location

Vindolanda is in the north of England , on the border with Scotland , in the Pennines hills , in that part of the island where the distance between the coasts of the North Sea and the Irish Sea is the smallest. It stood about three kilometers south of Hadrian's Wall, on its most scenic section, the ridge of the Whin Sill, near Hexham and Haltwhistle , about 40 km from Luguvalium ( Carlisle ) in the west. The Roman fortress with its civilian settlements and burial grounds were located immediately south of Stanegate Street. The latter connected Corbridge in the east with Carlisle in the west on the Cumbrian coast. The fort stood in the trough valley of the South Tyne , on the eastern edge of a 154 × 93 meter large, slightly south-west sloping, 160-165 meter high plateau between the watercourses of the Doe Sike in the west and the Chainley Burn in the east. From there you had a good view of the densely forested Allen Valley and the low mountain range of the Pennines. To the east, visibility was somewhat restricted by Barcombe Hill and the Cod Law Ridge to the north. The latter mainly obscured the view of the Whin Sills ridge. This circumstance was probably of no great importance for the builders, since the fort was primarily intended to secure Stanegate Street. The terrain was otherwise flat enough and, above all, had sufficient water resources for a larger crew. Bradley and Brackies Burn initially unite below the plateau to form Chainley Burn, which in turn flows three kilometers away as Bardon Burn into the southern arm of the Tyne. The archaeological site is now accessible via the A69 (Carlisle-Newcastle dual carriageway). The closest ramparts were the Vercovicium (Housesteads) in the NE and Aesica (Great Chesters approx. 6 km in the NW) 3 km away . In the late 2nd century the region belonged to the province of Britannia inferior , from the 4th century to the province of Britannia secunda .

Road links

The roads laid out by the army in Northern Britain were vital for communication between garrisons and control of the newly conquered territory. The south of the British Isles, such as B. the commercial metropolis of Londinium and the canal ports can be reached in less than a week. Concrete witnesses for the connection of Vindolanda to the trunk road network are u. a. Imported dishes from Gaul and olive oil amphorae from Hispania . A text on the blackboard probably even refers to a trip to Rome. The shoe fashion in Vindolanda was also based on the contemporary styles that were also worn in the rest of the empire. Vindolanda was a stage on the Stanegate built by Agricola or one of his successors , which connects the Coriosopitum ( Corbridge ) supply base in the east with Luguvalium ( Carlisle ) in the west through the river valleys of the Tyne and Irthing , which cut through the Pennine hill country. The place was only about 24 kilometers from the main supply base of the wall garrisons, which was about a day's march. Despite the construction of the military road , which stretched closer to the wall, the Stanegate remained a heavily frequented route, as the former partly ran over difficult terrain that was impassable for ox carts. The name of the street comes from the Middle Ages , but its route was determined by Roman surveyors. In some places some of today's roads still follow his route, but a large part of the ancient route can only be recognized by means of dirt roads or borders. The Stanegate ran past the stone camp in Vindolanda immediately north, and a little further northeast it crossed the Bradley Burn. To the west it is marked by a sidewalk and by the access road to the archaeological park. Remnants of the ancient road surface are no longer visible on site. During the investigation of the north-west wall of the fort, it was also found that the previously assumed course of the Stanegate cannot be correct, as a defensive moat must have existed there at times. Supplementary aerial photo and magnetometer examinations therefore suggest that the route was about 50 meters further north of the fort. Road connections existed - via the Stanegate and its side streets - to Barcombe, to Fort Cilurnum (Chesters), to Crindledykes, to Fort Aesica (Great Chesters), to Grindon Hill, to the small fort Haltwhistle Burn ( Haltwhistle ), to Fort Magnis (Carvoran), to Newbrough , to Seatsides and almost certainly to the Wallkastell Vercovicium (Housesteads).

Milestones

Roman milestones were not only used to indicate the distance to the next stage. They should also emphasize the new installations and repairs ordered by the emperors or other honoraria . There is evidence that the governors in some of the provinces Hadrian visited had the roads restored to good condition a year or two before his arrival. The governor of Britain at this time was Quintus Pompeius Falco . Seven Roman milestones were discovered north of Stanegate about ¼ mile east of Crindledykes Farm in 1885. A copy is now in the Chesters Museum. According to its inscription, the distances on the eastern section of the Stanegate were measured from Corbridge. The replica of one of these stones was placed directly at the entrance to the show area, after the bridge over the Chainley Burn. The milestones that were set up along the Stanegate in the third and fourth centuries underline the ongoing importance of this strategically important east-west route for the Romans.

In 1725 the antiquarian John Horsley came across another intact milestone on Stanegate Street at Codley Gate, 120 meters northeast of the fort. It was 1.7 meters high, had a cylindrical shape and a rectangular base. The pages were only roughly smoothed and showed no traces of writing. According to Robin Birley, they were worn down by cattle over time. It may have originally only had a painted inscription and marked the 16th mile from Coriosopitum (Corbridge). The base of a second Roman milestone is still on the north side of Stanegate on the edge of the modern access road to Chesterholm, about 130 meters from the road coming from Once Brewed, i.e. i. 1.5 km west of the fortress. Around 1815 it was split in two and reused as a goal post. According to Horsley, he wore an honorary title for the incumbent emperor, probably Hadrian , and probably a mention of the Tungrian cohort. The stone is one of the two specimens that indicated the 15th and 16th Roman miles west of Corbridge. The distance between the two milestones is slightly larger than the standard length, possibly the so-called Drusian foot was used as a measure. They are also remarkable because they are still in their original locations.

Digs

The ruins of Vindolanda have been known since the 16th century, but only a few areas of the pre-Hadrian camps of Vindolanda have ever been completely excavated or examined in more detail. Their design was certainly similar to the wood and earth castles of the early imperial era. On the basis of information from better researched camps, one could interpret the structures excavated in Vindolanda , but with the reservation that none of the fortifications were completely identical. Hypotheses made for this can therefore only be confirmed by future excavations. Since 1970 the Vindolanda Trust has therefore carried out an extensive archaeological research program, during which smaller excavations take place every year.

The excavations between 1930 and 1980 already showed that there were several successive wood, earth and stone fortresses in Vindolanda . Numerous remarkable antique utensils were also found. These include, above all, the Vindolanda tablets . Every season, up to 500 archeology enthusiasts from all over the world take part in the excavations. Professionals, students and amateurs take turns at one location every two weeks. Visitors to the excavation site can tour the excavation areas, chat with archaeologists and volunteers, and witness new discoveries. The excavations so far have provided an extraordinary insight into the daily life of the soldiers and civilians who lived in this remote border region. The archaeological work of Eric Birley's descendants , Robin, Anthony and Andrew, is also closely linked to Vindolanda . The family home now houses the Vindolanda Museum, which presents artifacts recovered there and information about the history of the fort. It is currently estimated that it will take another 150 years to complete the excavations in Vindolanda .

The stratigraphic and hydrological conditions on site are often extremely difficult for the excavation teams. The demolition and reconstruction of the buildings, which lasted over four centuries, has left a complex sequence of layers. The remains of the early wood-earth stores are in places up to six meters below the current layer of soil. The wall sections of the last construction phase limit the access to only small areas. The most important excavations of the pre-Hadrian fortresses took place, for example, in a narrow green strip between the western wall of Fort IX, which has not yet been excavated, and the buildings of Vicus II. The investigation of these deeper layers is therefore extremely laborious and the creation or interpretation of floor plans of the building structures discovered there is fraught with great uncertainty. Only a small part of the early forts that lie below the stone fort and the vicus have been excavated so far. You can only work in the summer months. The biggest problems here are the high groundwater level, fed by the frequent rains and numerous small springs that arise on the Vindolanda plateau. The differentiation of the construction phases has therefore always proven to be very difficult, since z. B. in the course of the planned demolition of the old buildings often their - still usable - wooden beams were removed and reused in the new construction. When the stone fort was built, the last remnants of the wood-earth camp were also severely disrupted or disrupted.

Research history

16. – 19. century

The oldest known evidence of Vindolanda comes from the antiquarian and historian William Camden (1551-1623), which he wrote down in his work Britannia (1586). Before the beginning of the 18th century, it was very dangerous to stay in this area without an armed escort, as it was a retreat for outlaws of all kinds (so-called border reivers ). During the next 200 years or so, scholars and travelers visited the area again and again. It was only when the former border region was opened up by mining in the course of the industrial revolution that archaeologists were able to move a little more safely there. However, a large number of people looking for work now also settled there. The eyewitness accounts of these early researchers are valuable historical documents, as they were able to study the ruins of Vindolanda before the massive stone robbery in the late 18th and early 19th centuries through land enclosure. Before 1702, the walls of Bath House II must have been almost completely preserved, as Christopher Hunter described the building as still partially roofed. He not only recorded his own observations, but also interviewed the local population. In 1716 the tax clerk John Warburton came across an altar stone of the goddess Fortuna which he had removed. It was donated by a centurion, Gaius Iulius Raeticus. John Horsley founded the systematic exploration of Vindolanda. In his work Britannia Romana he reported in 1732 a. a. from an inscription from Beltingham, which later turned out to be a building inscription from one of the castle gates. In 1765, John Wallis mentioned a temple building with richly decorated columns on the western edge of the vicus which was completely destroyed by stone cutters. He also reported from a burial ground in the hallway Archy's Flat. From 1814, the pastor Anthony Hedley had scientifically guided excavations carried out for the first time and the east gate of stone fort IX was exposed. Hedley also examined the remaining gates, the Praetorium, and the northeast corner. The fort walls were partially up to 4 meters high at that time. Hedley also built the Chesterholm manor house in 1831 in order to better monitor the excavations from there. He died in 1835 before he could write down his findings. With his death the first phase of the archaeological exploration of Vindolanda came to an end. In 1858, Henry McLauchlan drew up the first survey plan for the stone fort. Since it was not completely excavated at the time, he made it using the visible elevations in the ground. In 1864 John Clayton bought Chesterholm and had most of the inscription stones recovered there set up in the house. Until 1878 only minor investigations were carried out.

20th century

In 1929 the Chesterholm lands came into the possession of the archaeologist and offspring of a wealthy textile manufacturer, Eric Birley (1906-1995). In the 1930s he was commissioned by Durham University with extensive excavations. In the course of this, the surrounding walls and the staff building were exposed. From 1931 onwards, the first excavations were carried out on the grounds of the camp village. Due to the outbreak of war , these investigations had to be stopped again in 1939. Birley turned his property over to the Ministry of Works . The praetorium, three gates and individual sections of the fort wall were preserved and made accessible to visitors. Shortly after the end of the war, in 1946, Birley carried out new excavations in Chesterholm with the help of German prisoners of war. He had recruited her for this job because of her work in the British secret service and her archaeological training. Some of them later became active in this research field again in Germany and remained on friendly terms with their British colleagues throughout their lives. In the following decades only minor excavations were carried out (1959). In the late 1960s, archaeologists first examined the well-preserved remains of the stone fort and vicus from the 3rd and 4th centuries. Further research was carried out by the Durham University excavation committee from 1969 onwards. I.a. Drainage work was carried out on the vicus area, revealing the extensive remains of the civil settlement. Only when Chesterholm was transferred to the independent Vindolanda Trust, which was founded at the time, did this lead to a new upswing in archaeological exploration of the area. The foundation paved the way for the excavations, which were carried out regularly in the decades that followed, under the direction of archaeologists Robin and Andrew Birley, the two sons of Eric Birley. Bathhouse II was completely excavated between 1970 and 1971. However, it has not yet been possible to date it without a doubt. His area was also acquired by the Vindolanda Trust. 1985–1989 the southern part of the central sector and an area next to the Via Principalis of the expanded Fort II were examined. Since 1999, excavations lasting over six months have taken place in Vindolanda every year.

21st century

During excavations on the western edge of the extramural zone in the period 2004-2006 stone foundations from the second century were observed in the vicus . In 2008, the two warehouses were uncovered and preserved. Other large-scale campaigns began in 2016 and continue to this day. 2017 were u. a. Cavalry barracks discovered, which brought a wealth of new interesting finds to light. Anaerobic layers from the year 120 AD were exposed under the foundations of stone fort IX, i.e. from the time shortly before the construction of Hadrian's Wall. At that time the fort (phase IV) was occupied by two units, the Tungrian cohort and a division of Vardulli cavalrymen from northern Spain. Remains of wooden walls, floors, fences, animal bones and wooden objects could be recovered there. In one of the barracks there were also numerous militaria, leather shoes worn by men, women and children, as well as combs, hairpins and brooches. Other personal items included wooden writing boards and pens, knives, and two wooden toy swords. A special find was a riding sword ( Sparta ) that was still in its wooden scabbard. The pommel and handle were also still intact, only the tip of the blade was slightly bent. The second sword was discovered in an adjoining accommodation, but in this case only the blade remained. The two found objects were apparently still exactly where they had been deposited 2000 years ago. That they had been left behind could indicate that the crew had to leave the fort in a hurry. Among the rest of the militaria found there were spearheads and arrowheads and bolts for ballistae that were strewn all over the floor of the barracks. The excavation team also found perfectly preserved copper utensils for horse saddles. Another unique feature is a centurion's helmet bush, which has survived almost undamaged because it was made of moss fibers. Probably the first Roman fortification of Vindolanda was discovered only recently. It was located north of the fort, which is still visible today, and probably dates from the early 1970s AD. It could have been a temporary marching camp.

Find spectrum

The around 500,000 finds that have been recovered so far can be combined to form an extremely interesting overall picture of everyday life in the border garrison. The anaerobic, boggy and humid conditions in these culture layers have also preserved finds made of organic materials in earlier waste pits, which would normally have long since decomposed in the soil over such a long time. Every time the fort area was leveled after a demolition, an airtight layer of clay was created, which almost perfectly preserved everything buried under it, including the organic. These included textiles, leather goods, wooden objects and remnants of ancient flora and fauna. It is becoming increasingly clear that many of the northern European tribes were unfamiliar with the techniques of tanning before the Roman conquest. The skins were either treated with oils or fats or smoked and then processed further. Since none of these preservation methods produce durable and water-repellent leather, such leather artifacts are only preserved under exceptional environmental conditions such as extreme dryness, high salt content or in peat bogs, where a kind of secondary natural tanning process takes place. In contrast, tanning with plant extracts results in a chemically stable product that is resistant to bacterial infestation and survives centuries particularly well under moist, low-oxygen conditions. The residents of Vindolanda also had an idiosyncratic view of hygiene in their living rooms. Obviously fresh layers of bracken , straw and gorse were poured onto the floors from time to time without sweeping the garbage out of the houses. Over time, layers were laid on top of each other and compressed. As a result, mat-like conglomerates of rubbish and plant residues were sometimes up to 45 cm thick. When they were rescued, they were cut out like peat bricks and brought to the investigation in blocks of 2 to 3 meters in order to salvage the organic finds. In addition to a selection of finds presented in the Vindolanda Museum, the most important pieces of the older excavations are in the British Museum in London .

Human remains

In 2010, during excavations in the corner of a fort barrack from the middle of the 3rd century, a skeleton was discovered that was initially thought to be that of a canid . In 2012, however, research at the University of Durham under the direction of anthropologist Trudi Buck revealed that the find was the remains of an approximately nine to eleven-year-old child who lived in the period after 213 to the middle of the 3rd century Earth came. The garrison force at that time was the Cohors IV Gallorum . The analysis of the teeth revealed that it had grown up in the Mediterranean area . Until the child was seven or eight years old, it was either in southern Europe or in northern Africa . However, it could no longer be clarified whether the poorly preserved bones were those of a boy or a girl. In Roman times it was customary to bury or cremate the deceased in cemetery on the outskirts of the city. Hiding a corpse inside the camp raises suspicion of a deliberate criminal act. The forensic examination, which showed that the wrists were handcuffed as well as massive skull fractures , further corroborated the assumption that the child died violently and was then buried under the floor of the barracks. Or maybe it was an accident and an attempt was made to cover it up in this way. Whether it was a slave or a member of a soldier's family remains in the dark for lack of evidence. The Romans' keeping of child slaves is well documented, which may explain how it got from its original homeland to northern Britain. Upon completion of the forensic examination, the skeleton was given to the Vindolanda Museum.

One particularly gruesome find was an 1,800-year-old British-born skull that had apparently been impaled on a pole. The skullcap showed numerous signs of injury, caused by sword blows, which probably also led to the death of this man. The victim came from northwestern Britain, as determined by isotope analysis of his teeth. The traces of damage clearly show that the head was cut off and then placed on the stake. The taking and displaying of head trophies was common among Roman auxiliary soldiers.

Animal remains

A variety of animal bones, including ox skulls pierced with holes, were also uncovered during the excavations, suggesting that they were used by soldiers for target practice. Animals that left their traces on ceramic or brick fragments were from domestic dogs ( Canis familiaris ), more than 80% of these traces come from him, as well as from wild cats ( Felis sylvestris ), domestic pigs ( Sus scrofa ), sheep ( Ovis ammon ), Goats ( Capra hircus ) and cattle ( Bos taurus ). The complete skeleton of a dog was discovered in one of the storehouses of Fort IX. Two larger bone dumps are about 200 years apart. One was in the western moat of the stone fort, presumably the residents of the vicus had disposed of their leftovers there in the 4th century. The older landfill was mainly filled by the soldiers from the wood and earth forts.

leather

The Vindolanda Trust also has the largest collection of Roman leather artifacts, including 6,000 shoes of all sizes and styles, saddle covers, bags, buckets, purses, and an archer's thumb guards. The name of their producer was stamped on many of the shoes. One of them, Lucius Abucius Tales, son of Titus, made particularly exclusive and expensive footwear. Some of his sandals were only thrown away because the toe strap was torn, which would have been easy to fix. A sign of a certain prosperity among the upper classes, even in a remote place like Vindolanda . During the archaeological excavations, however, there were also clear indications of material recycling. Some remains of shoes show that pieces of leather have obviously been reused several times.

A particular archaeological stroke of luck was the discovery of three leather tents (tent I-III) from the 2nd century, which had been used by the common soldiers. Tent III was particularly well preserved. Old tarpaulins were often cut up and sometimes reused for repairs. The specimens from Vindolanda, along with a considerable number of other worn and damaged pieces of leather, had been thrown into a rubbish pit when Fort II was demolished. Tent III was obviously old and in very bad condition when it was deposited. It had been patched several times with pieces of leather and probably dates from the time of Fort II (90-100 AD). The tarpaulin was sewn together from around 50 square goatskin segments and weighed 45 kg. About 75 goat skins were required for a tent this size. This is much lighter than cowhide and was very suitable for making such tents. Smaller elements such as eaves flaps, reinforcement patches, tension cords and seam reinforcements were for the most part obtained from the cut remains. Bill Mayes noted that such a tent must have weighed about 8 kg more in the rain. The tarpaulin was stretched over a wooden frame when it was erected. Until now it was assumed that the Roman specimens were mainly supported with bars and held in shape by the tensioning ropes, which would have resulted in a rather low height of only 120 cm. After examining the find in Vindolanda, it became clear that the tent was 185 cm high above the frame with a roof pitch of 60 °. The wall height was 110 cm. The tension ropes were used to stabilize the leather over the support frame. Four leather segments were sewn together in an overlapping manner and served as a cover for the doorway. The leather fragments, some of which had already crumbled and were often incomplete, were cleaned and preserved in the laboratory of the Vindolanda Trust, so that they remained relatively supple and had only shrunk slightly. Torn and damaged segments were partially restored or supplemented, so the tent was almost completely restored.

textiles

The excavations also produced the largest collection of ancient textiles (mainly made of wool) from the military sites in the western provinces of the empire. Most of the fragments, however, are too small to recognize their former function. But they provided a lot of new information about the web technologies of that time. Apparently clothing was also produced in Vindolanda , Table 192 mentions a shipment of 38 pounds of wool. But clothing also formed a large part of the supplies. Very few textile finds were still complete when they were recovered, including a children's sock.

Wood

The structural remains of the pre-Hadrian camps, which elsewhere mostly consisted only of post impressions in the ground, were in many cases preserved in Vindolanda as almost complete structures and offered archaeologists the very rare opportunity to study Roman woodworking techniques. The woods also offered the possibility of their very precise dating by means of dendrochronology . Of the other wooden objects, wagon axles, pieces of furniture, tent pegs and combs deserve special mention. The writing board no. 51 contains the settlement of a material delivery ( materias ). It consisted mainly of wheel hubs, car axles, spokes, bed axles and seats. References to barrows can also be found in Plate 316, according to which they were requested for the transport of stone material. It seems that the soldiers in Vindolanda , a wagon- operated, that is, that there carrulis either repaired or have perhaps made.

Ceramics

A considerable amount of the pottery finds date from the third and fourth centuries. A special collection of 111 fragments was put together from these, on which tread seals of animals (see also above) can be seen. Some also have finger and hand prints, as well as prints from tools, nails, textiles, and pieces of wood.

metal

The metal finds consisted mainly of jewelry, bronzes and weapons. A particularly large number of weapons, spear and arrowheads, and slingshot came to light in the Vicus II. Presumably, the security situation had worsened massively in the 4th century. But also special tools like an iron awl to be able to pull the armor's straps tight, an iron knife with the blacksmith's name, Jovinus, stamped on it , and a capsule with sewing needles. A doctor's set discovered in Vindolanda consisted of tweezers , a silver probe for opening wounds, and a narrow bronze knife that was used for amputations . The trademark of the Vindolanda Trust was a horse statuette about eight centimeters high, represented in the so-called Spanish step . The bronze figure was found in 1971 under the floor of a house in Vicus I (corridor house). Due to the polygonal spout on its underside, it is assumed that it originally served as an ornament or closure of a standard pole. In the same building a gold ring with a carnelian gem was found , which bore the inscription "ANIMA MEA" (my soul / heart / darling). Another gem with the image of the deity Silvanus came to light under the doorstep of the southwest room.

Coins

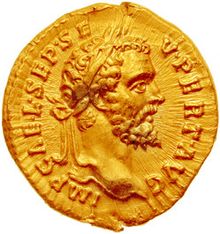

On August 8, 1837, quarry workers discovered a bronze container that held 63 Roman coins near the Langstone at Thorngrafton. The coins (three gold and 60 silver pieces) came from the period between the reigns of Claudius (41–54) and Hadrian (117–138). They were probably hidden in the quarry in Hadrianic times. The purse is now in the Chesters Museum, the coins are missing. At the end of the 19th century, 300 coins were recovered from the ruins of the west gate. They provided evidence that the fort was still inhabited in the 4th century. In Bath House II, coins from the time of Marcus Aurelius (161–180), Septimius Severus (193–211) and Alexander Severus (222–235) came to light. Further specimens (nine bronze sesterces ) that had been minted during the reigns of Domitian (81–96) and Marc Aurel were found in the latrine drain . In 1976 a hoard of 62 coins came to light in the mansio near the east wing; they were minted between the middle and the end of the 2nd century (Antoninus Pius, 138-161) and Marc Aurel (161-180). At the same place in the corridor area another hoard of 111 items was found, which was found in 1976 in the uppermost layer of destruction of Vicus II and which was of great importance for the dating of the two Vici. This find and the lack of coins from the time of Tetricus I (270–273) indicate that the civil settlement was destroyed or abandoned by 270 at the latest. In 2011, 21 silver denarii were secured in the head building of a barracks from the late Cantonese period (180-200) . The coin hoard had been buried in a shallow pit under the mud floor in the center of the room, possibly in a bag or some similar envelope made of organic material that had rotted away over time. The archaeological context suggests that the coins were deliberately buried and not lost. Probably it was about the savings of the then resident. The coins were given to the Vindolanda Museum. The last of a total of eleven coins found from another hoard was one from the reign of Valens (364–378). The most recent coin discovered in Vindolanda dates back to the time of Valentinian II (375–392).

Inscriptions

In Chesterholm, 47 Latin inscriptions on 24 altars and votive stones, 6 building inscriptions (one undated), on 4 centurial stones (so-called slab stones), 6 gravestones and 7 other - illegible - inscription artifacts, including 4 Voussoir stones, each with a Roman numerals were provided. Among these finds was a fragment of a military diploma for a soldier from the Tungrian cohort.

Writing boards

Among the most remarkable finds from Vindolanda are the writing boards ( sectiles / laminae ), which have also become internationally known , which provide insights into everyday events in this border region in the years before the construction of Hadrian's Wall. They were recovered from the ancient buildings and garbage pits in the course of several excavation campaigns in the 1970s and 1980s. Subsequent excavations in 1974 and 1975 increased the total number to over 200. A further 400 specimens appeared at the south gate in 1993 and some after 2000. Up until then, only a few fragments were known, including the concentration of such an amount in one place is unique. The finds today include the largest collection of Latin documents ever discovered. The panels contain valuable information on palaeography and the development of this language. Most of the Roman sites in Britain only know the names of a handful of people, mostly from inscriptions, brick stamps or wall graffiti . In contrast to this, more than 600 individuals are named in the writing boards, they were the authors or recipients of letters, as well as persons referred to in accounts or lists. The boards sometimes also reveal additional information about certain people, mostly their rank, but also their place of origin and their family or friendship relationships.

On the very well-developed roads in Italy, messengers in a cart, with regular changes of the draft animals, could have covered distances between 50 and 80 miles per day; mounted messengers managed this almost certainly. Such travel speeds were probably not possible in Northern Britain. Corbridge messages to Carlisle could well have been answered within a day. An embassy could have reached York in two days, London within a week, and the home provinces of the soldiers stationed in Vindolanda in northern Gaul within two. Many texts refer to repeated correspondence. Complex business transactions depended on the rapid exchange of information. A letter from Octavius to his brother Candidus mentions receiving or sending letters several times and points out that communication and the transport of goods keep breaking down because of the bad roads.

The panels - mostly broken when they were recovered - were about the size of a postcard and were made of locally abundant alder or birch wood, which could be processed easily and cheaply. A letter usually consisted of two panels tied together at the top with a thin leather cord threaded through two holes. The address was scratched on the outside with a stylus. The text was applied with ink on both inner sides. They contain messages, lists or records. The plaques were mostly inscribed between 90 and 120 AD, when the fort was occupied by the Cohors I Tungrorum and the Cohors IX Batavorum . They come from the period between the conquest of North Great Britain in the second half of the 1st century and the erection of Hadrian's Wall from the year 122, i.e. from the least known epoch of the Roman occupation. The tablets also provided ample evidence of communication between the Vindolanda garrison and units at Carlisle, Catterick, Ribchester, Corbridge and Binchester. When the Bataverkohort withdrew, the archive of the camp commandant's office was thrown into the fire, but it was quickly extinguished again shortly afterwards by a downpour; the cremation site was located near the south gate of Fort III. Due to this historical stroke of luck, u. a. the correspondence of the cohort prefect Flavius Cerialis, commandant of Fort III, received for posterity. The special soil conditions on site had kept the tablets in a good state of preservation, so that many of them could still be deciphered. In this context, Alison Rutherford from Newcastle University developed a method to make the ancient writing legible again using infrared photography.

The tablets were transcribed and translated by papyrologists Alan Bowman and David Thomas. They provided groundbreaking insights into ancient writing, the development of Latin cursive script and details on Roman military and provincial history. Most of them contain short messages, military reports and vacation requests. The military regulations and other administrative documents relating to everyday garrison service were of great importance for research. They revealed more information about how the Roman border sections were organized. In addition to the official ones, the texts often also concern the private concerns of the officers, their relatives and slaves. The private correspondence of the wives of the camp commanders, food requests, and personal letters to the soldiers and their replies were also found. Even a student 's notes on Virgil 's Aeneid survived. They are the oldest surviving handwritten documents in Great Britain. Chance finds at other British excavation sites, such as Carlisle and Caerleon , Wales , suggest that they were not unique. The large quantities that could be recovered in Vindolanda rather suggest that they were ubiquitous as writing materials in the office (Officia) of the northern provinces, especially since papyrus was naturally extremely scarce there.

Others

In the changing room and drains of bath house II, numerous hairpins, pearls, oysters, game stones (cubes) and combs made of boxwood came to light. They prove that the thermal bath was also used by civilians.

development

Vindolanda was founded in the first phase of the establishment of the northern border of Roman Britain, in the decades before the construction of Hadrian's Wall. The fort was part of the border security systems of the Roman Empire from the 1st century until the end of Roman rule in the early 5th century. According to Notitia Dignitatum , in the 4th century it was part of the fortress chain of Hadrian's Wall ( per lineam valli ) , despite its spatial distance from the wall zone . The camp probably secured the gap between the ramparts Housesteads (three kilometers northeast) and Great Chesters (six kilometers northwest). It was also an important stage in the network of forts and roads in Northern Britain. The forts were built by the soldiers themselves and housed a militarily organized, largely self-sufficient community. I.e. the soldiers were able to cover a large part of their own daily needs, including food production and the manufacture and repair of everyday objects. Nevertheless, this military base, in which over 1000 regularly paid soldiers and their relatives were stationed at times, attracted craftsmen, farmers and traders from the surrounding area or more distant provinces of the empire. The garrison not only offered them protection in this remote outskirts of the empire, but above all a regular income in coins. The on-site infrastructure, such as bathhouses, running water, a hospital and various temples, was otherwise only to be found in the larger cities in the southeast of the island. However, the fortress was by no means completely independent and relied on regular interaction with the outside world. According to the writing boards, goods of all kinds were delivered to Vindolanda every day . The soldiers patrolled along the border and came into contact with the crews of the neighboring forts. The general security situation was obviously stable enough for the wife of the garrison commander of Vindolanda to be invited to another border fortress by an officer's wife who was friends. According to the boards, a trader was more concerned about the poor condition of the roads than being mugged and robbed by highwaymen on the way. The exchange of goods and the almost undisturbed travel movements of the people living there made it possible to maintain an upscale Roman lifestyle, at least in the camp commandant's household.

1st century

Under Emperor Domitian , the governor of Britain, Gnaeus Iulius Agricola , led his army and fleet to the northernmost edge of Britain. There he still managed an overwhelming victory against the indigenous tribes in north-east Scotland in 83. The battlefield was on Mons Graupius , who was probably near what is now the city of Aberdeen . With this the Romans had completed the conquest of the British Isles, but complete and permanent control of the tribal areas in Caledonia (Scotland) was apparently not in the strategic and economic interests of the imperial court. Despite the considerable military efforts, which included the construction of a legionary camp in Inchtuthil and numerous cohort forts and watchtowers, a reduction in the provincial forces led to a comprehensive revision of the military operation in the north. Most of the expedition army was recalled by Emperor Domitian to drive the chats out of the Wetterau on the continent . Under Trajan (98–117) the forts in the Lowlands were also given up and the borderline on the Stanegate , a military road running from east to west, was withdrawn. This led directly past Vindolanda , which was permanently occupied with soldiers from 85 AD and must therefore have played a central role in the defense of the British Limes. It is believed that Vindolanda has had a fort since the late 1st century AD. It is believed to be south of the Stanegate. The remains of a larger Roman fortification were actually found there, but they could not be dated. If it actually came from this period, it was probably founded by Agricola between 72 and 79 or during the tenure of governor Sallustius Lucullus. The latter ordered the gradual withdrawal of the army from Scotland to use on the lower Danube. In 86 Rome had one of the four legions in Britain, the Legio II Adiutrix , moved to Dacia. With the departure of this major association and a significant number of the auxiliary cohorts, effective control of Scotland was no longer possible. The fort was rebuilt around 92 and significantly expanded to accommodate a mixed unit of infantry and cavalry ( cohors equitata ) - in this case the ninth Batavian cohort. Further modifications were made around 97. At times, up to 1,000 soldiers and their relatives, slaves and freedmen were staying in the fortress.

2nd century

In 104, when the Batavians were also moved to Dacia, the fort was destroyed as planned. Abandoned briefly, the site was reoccupied and rebuilt around 105 by the first Tungrer cohort. There is evidence that the border area was repeatedly threatened by barbarian tribes between 110 and 118. The gravestone of a centurion was found in Bath House II, presumably it had fallen in the fighting. On one of the writing boards (No. 32) a member of the army described the combat equipment and tactics of the indigenous tribes, which he dubbed "Brittunculi" (wretched little Britons), who use too many riders in battle and do not stop for theirs when the enemy rushes Throwing spears. This expression first became known to researchers there. The letter can be a report or a remark on the suitability of the British as recruits, or just a personal assessment that an officer has left for his successor. The fort was considerably expanded several times within a few years after its completion and was now part of the new fortress chain along the Stanegate, which was built by the governor Neratius Marcellus . Presumably he - temporarily - also set up his residence in Vindolanda (see also Vindolanda boards ). Even after the decision to build a border wall further north, the Stanegate camps still fulfilled an important function. The border troops were initially housed there until the high command made the decision to build the new camps directly on the wall. When Hadrian's Wall was built, Vindolanda probably also served as a base camp and logistics center for the central wall zone. After the fort in Housesteads was completed, his garrison was apparently moved there in 125 years. Vindolanda was abandoned for a few years. In 140, Emperor Antoninus Pius ordered the reoccupation of the Scottish Lowlands to secure his status as Emperor. The border was pushed forward to the line between what is now Glasgow and Edinburgh and secured by a new wood and earth wall, the Antonine Wall . Nevertheless, Vindolanda remained occupied and was gradually rebuilt in stone during this time. The presence of the Romans in this part of the island was only a brief episode. Already around 160, before the death of Antoninus, a large part of the army was withdrawn to Hadrian's Wall. At 162 he was again occupied in full length with troops. The Stanegate remained an important connection and supply route, even after the military road was built not far from the wall in 160. The withdrawal of the border on Hadrian's Wall meant that Vindolanda was reoccupied with a new unit, although this section had remained relatively quiet at the time. The favorable position of the fort made it possible, however, to monitor and protect the traffic on the Stanegate between the Carvoran wall fort and the Irthing crossing near Chesters. Perhaps from then on Vindolanda also played a key role in supplying the wall garrisons, similar to Coriosopitum in the east of the border zone.

3rd-9th century

When Emperor Septimius Severus marched his army into Scotland at the beginning of the 3rd century, the fort was abandoned again and largely demolished to make room for the erection of 300 round huts, these were removed again around 211. Its foundations still partially protrude from under the north wall of Fort IX. When Severus died in Eburacum (York) that same year , his son and successor Caracalla made peace with the Caledonian tribes and withdrew his troops behind Hadrian's Wall. In 213 a new stone fort was built in Vindolanda . The same was repaired or rebuilt around 300, the civil settlement was obviously abandoned or destroyed around 270. The garrison was probably already very thin in numbers, so that civilians were also allowed to settle within the fortress walls. There are still some references to the last repairs that were carried out until 370, after which the fort was apparently no longer occupied by the regular army. In the Notitia Dignitatum Occ. (late 4th century) all fortresses along the wall are listed, but only Vindolanda appears from the Stanegate camps . Although Hadrian's Wall was abandoned in the early 5th century, the fort was still inhabited for over 400 years, and traces of post-Roman burials could be seen near the fortress. Some evidence also suggests the existence of an early Christian church before it was finally abandoned by its residents in the 9th century. Since Vindolanda is located in a remote area, far away from larger towns or cities, it was initially not as massively damaged by stone robbery as other Roman settlements, the systematic destruction of which often began in the early Middle Ages. For example, the roof of Bath House II is said to have been - partially - intact until the 18th century. The massive stone robbery probably did not begin until the 19th century. From then on, the stone material of the fortress and the vicus was used for the construction of farm buildings, field walls and churches.

Castles

Like many of the Roman castles, those of Vindolanda have been repaired, rebuilt and then removed again and again over the centuries. Over the years, the excavations in Vindolanda have revealed a sequence of at least five wood-earth camps that preceded the three later stone forts, which is very difficult to determine in terms of building history. So far, a total of nine construction phases could be distinguished. West of the late antique Balineum , on the north side of the Stanegate, the alleged parade ground of the fort could be made out on aerial photographs. One of the fort's construction stores was also likely to have been located next to it. The main entrance to the fort was the north gate, the Porta Praetoria , in the front part of the fort ( Praetentura ) there were barracks, small shops and workshops on both sides of the north-south main street ( via Praetoria ). It led directly to the entrance of the headquarters ( Principia ), in the central fort area ( Latera Praetorii ). The west-east main street of the fortress, the via Principalis , ran in front of the camp headquarters . This was also the home of the commandant and his family ( Praetorium ) and one or more granaries ( Horrea ). There were often functional buildings such as workshops ( Fabrica ) and a hospital ( Valetudinarium ). In the rear half of the fortress ( Retentura ) there were four more barracks blocks. Another street ( via Sagularis ) ran directly behind the wall and spanned the entire fort. The bathhouse was outside the fortress because of the high fire hazard.

Wood and earth forts

The forts listed below were built according to the early imperial building scheme (layout, playing card shape, axis from east to west).

Fort I (85–92)

It covered an area of around 1.4 hectares, was repaired several times and partially rebuilt. This construction phase could be dated with the help of ceramics, which had been thrown into the moat after 90 AD at the latest. It was in approximately the same position as the stone fort IX, which is still visible today, was about 6 meters lower and could therefore only be explored in a rudimentary manner, as otherwise the layers above would have been too severely disturbed. Three moats ran in front of its western wall. To the east, north, and south the camp extended to the slopes of the plateau. Furthermore, the course of the road to the west gate could be determined. The fort was also surrounded by a V-shaped ditch, which was interrupted by two earth dams. On the west side it was 4.5 meters wide and up to 1.5 meters deep. It is possible that there were other weir trenches further west. Additional obstacles to the approach could have been thorn hedges, pitfalls with sharpened stakes and iron toe bars.

Castle II (92–97)

After the demolition of Fort I, the area was leveled and a layer of clay was poured in. The former trenches were also filled in. Some wells were only temporarily covered with beams. The new warehouse, twice as large, was built with inferior (i.e. freshly felled) wood from alder and ash, and apparently in a hurry. It was slightly larger than Fort I, stretching 100 meters further west and covering an area of just over 2.8 hectares. The boundaries of the fort could only be precisely determined in the south and east. Its originally more than 3 meter high defense consisted of a 4.5 meter wide lawn brick wall at the south gate, secured by a wooden palisade as a parapet. It is believed that it was originally intended only for the 1st Tungrian cohort. But as well as the IX. Bataverkohort was stationed in Vindolanda , it probably had to be expanded quickly. The south gate had only one passage and, soon after its completion, obviously had stability problems caused by a spring over which it was built. Remnants of the western barracks blocks and the - presumed - house of the commandant were observed from its interior. Its west wing was around 46 meters long and had twelve rooms. The building, which is at least 11.75 meters wide, stood directly above the west ditch of Fort I. Notes for the manufacture and repair of metal goods and leather processing indicate that workshops were also located there. The course of the Via Principalis was also determined during the excavations .

Fort III (97-105)

During this time the camp was repaired and expanded a little to the west. This increased its area to 2.8 hectares. Fort III was very similar in size and location to that of Phase II. The repairs had been made with much better wood material. The location of the south gate of the fortification is known; it was relocated two meters to the west because it was lowered into the moat of Fort I. Its position is now marked by eight wooden posts. The fort was also surrounded by a moat. There were also probably wooden towers at the corners. The position of the south gate was marked with six piles after the excavations. The sill beam and a number of beams inside the gate that served as the road surface were also reconstructed. Most of the other buildings were made of oak logs. Some streets, remains of the western barracks and, in particular, the praetorium and the bathhouse outside the south-east corner could be examined. The position of the Praetorium is particularly unusual. A building of this importance is expected to be in the center in an east-west orientation on one side of the Principia and not on the road to the south gate. Further archaeologically important buildings of the castles II / III are the wooden houses that were examined on the east side of the street. They were probably also part of the Praetorium. The fort remained in the ground plan similar to the previous building, but was expanded much more generously. Its construction quality had also improved significantly compared to the previous period. Oak was used again as construction timber and some rooms were covered with wooden floorboards. The living quarters of the officers and their families are probably located under Fort IX and are therefore inaccessible. The rooms at the southern end of the west side that could be excavated appear to include a large courtyard, kitchen and storage room. Extensive evidence of manual activity (metal and leather processing) also came to light. This could also mean that the building was the workshop ( fabrica ) of the fort. Such buildings were often very similar to the praetories . However, the discovery of the correspondence of the garrison commander and letters from his wife indicate that the building was actually the commandant's house. The first 347 writing boards were recovered there, most of them from the archives of the Prefect of the IX. Batavian cohort, Flavius Cerealis, were from. In addition, there were some other remarkable Roman artifacts such as the remains of a woman's wig, leather shoes (women’s and children’s shoes), which had been preserved very well under the almost oxygen-free conditions in the ground.

Castle IV (104–120)

After a short period of vacancy, a new warehouse was built, but with a different arrangement of the internal buildings, which was occupied by troops up to around 120. With an area of over 3 hectares, it was the largest fort built in Vindolanda . The renewed leveling of the area increased the ground level by over 2.5 meters. The fort was probably completed around 106. It is likely that his garrison was helped by cavalrymen and legionaries in the construction. The north gate and a section of the south wall are known of the fence. The south gate of Fort III was blocked and a new one was built, but its location could not yet be determined. A hall-like, west-east-facing, rectangular wooden building was discovered on the west wall, near today's parking lot. Its purpose is unknown but suggests the presence of legionnaires. The positions of the praetorium, a house with an inner courtyard (camp hospital?), That of the southern barracks with the head buildings of the centurions, porticos and 14 contubernias as well as some streets could be determined on the interior structures. The west wing of the Praetorium of Phase III was built over with a barracks block, the portico of which was later walled up. Its southern end was sealed off from the other chambers, perhaps the living quarters for the NCOs. Despite the generally poor state of preservation, the felling date could be determined for the first time from one of the wood finds using dendrochronology (104 AD), although it is also possible that it was used a long time after the tree was felled.

Fort V (120–140)

The finds from this period were not particularly informative, so the construction periods V and Va were difficult to distinguish from one another. The end of this construction period was not easy to determine and also not to be related to the next phase of construction, in which the fort was reduced in size and some, if not all of the buildings were rebuilt in stone. The transition dates between the year 120 and the middle of the second century. Around 120 the defenses were apparently completely renewed and the interior buildings were also rebuilt, probably in preparation for the visit of Emperor Hadrian (117-138). It was the last fortress to be built using the wood and earth technique. Presumably it remained occupied until around 150. Since it was almost in the middle of the rampart zone about 1.6 km south of Meilenkastell 39 , the fort could have served as a base camp for the construction of the central sector of Hadrian's Wall. It was probably demolished in 140 when the rampart was completed and in the late 130s only the Vallum was built. The interior of the Praetorium, a house with an inner courtyard (camp hospital?), Workshops on the western wall, a shoemaker's workshop on Via Praetoria and a presumed dining room with a large oven could be examined. The barracks block had been torn down and the area leveled. During the excavations, two successive buildings could be identified. Their construction quality was clearly superior to earlier periods. Stone slabs were used as the flooring and the wooden beams were larger and better processed. The extensive evidence of metalworking and robust architecture suggests that the building was a workshop ( fabrica ).

Fort VI (140-160)

The camp was established at the time when Hadrian's Wall was abandoned and the Antonine Wall was built on the Clyde-Firth of Forth line as a new border barrier. Fort V was leveled and its area backfilled with a layer of clay. The new fortress covered an area of 1.61 hectares and was located almost exactly above Fort I and under the late antique stone fort IX. At first it seems to have been raised again using the wood-and-earth technique, but it is possible that around 160 its stone walls were rebuilt. Its area was examined in the 1930s together with the north and west gates. Its convenient location on Stanegate was possibly the reason for the stone renovation. A section of the west wall, the west gate and the rounded south-west corner are known of the defense. In front of the western wall, three weir ditches had been dug as obstacles to approach.

Stone fort

The remains of the stone camp, still visible today, date from the 3rd to 4th centuries. It was still executed in the rectangular floor plan with rounded corners (playing card shape, orientation from north to south) typical of mid-imperial forts and measured 155 × 93 meters (1.5 hectares). A total of five construction phases could be determined at the stone warehouse. The stone material was believed to have been extracted near Vindolanda from a quarry at the southern end of Barcombe Hill and from a rock face at Chineley Burn, less than 130 meters east of the fort.

Fort VIa (160–208)

It originated when the Antonine Wall was abandoned and the army withdrew from Scotland. The wood and earth fort was demolished around 160 and - according to a building inscription - completely rebuilt in stone in 163. It stood on the eastern area of the much larger wood and earth fort IV, but had a different axis orientation (northwest). The entire circumference of the fortification is known, as is the position of the west gate and the east gate, which are flanked by two internal towers. Later an annex was apparently added in the west . The fort was surrounded by a moat that could be seen on the south-west corner. The Principia could be examined in internal structures. Its walls were made very carefully, which suggests legionaries as builders.

Fort VIb (208–211)

During this time, the existing fortress was either demolished or destroyed during fighting. Only its western wall and the associated gate remained. Apparently only the area of the vicus was temporarily fortified with a mud wall and a ditch. Inside there was a peristyle house and several barracks blocks. The peristyle house had several rooms, including a small bathroom. The rooms were arranged on three sides of the courtyard. This building was previously interpreted as an inn or hostel ( mansio ). However, it is believed to be the camp commandant's residence in the late second and early third centuries. The building was also surrounded by a mud wall, of which remains were observed during the excavations. Excavations in 1991 showed that part of the western wall of Fort VI was removed to connect the building to the camp area. In the third century it was demolished and the vicus was built over. On the other hand, there were numerous, very simply constructed, Celto-British round huts with stone foundations on the actual warehouse area. Their diameter was 4.27 meters, the foundations were 60 cm thick. They could be entered through doors 91 cm wide. However, no remains of stoves or fireplaces were found inside. Their purpose is unknown. Several theories have been discussed in this regard: Severus had a considerable number of hostages or prisoners housed here, it was the accommodation for irregular or newly recruited local army recruits, local workers or it served as accommodation in a refugee camp. Perhaps they were also used as flour mills. In 211 or 212 they were demolished again and the construction work for a new stone fort began at the same place.

Stone fort VII – IX (163–400)

The last three construction phases include the fort that was built from around 213 (period VII), renovated again in 368/369 and used by the regular military until 400. At 1.61 hectares, it was slightly larger than its successor and extended an estimated 16 meters above the north wall of Castle VIII. Castle IX was the last Roman fortification built in Vindolanda , measuring 155 meters (north-south) × 94 Meters (east-west) and covered an area of 1.4 hectares. The fort was almost completely rebuilt between 223 and 270, with only a few sections of the original west and east walls remaining. The new camp was relocated about ten meters to the south, and the western wall of Stone Fort VII was demolished along with its gate. In the late third century the vicus was abandoned or destroyed, with the exception of the third century bathhouse. In the final construction phase, significant changes were made to its interior buildings. According to the ceramic and coin finds that were unearthed during the excavations in the fort, it is believed that the military occupation ended in the early 5th century.

Gates and towers

The wall was reinforced by square watchtowers attached to the inside at the corners and broken through by four gates. The north gate served as the main entrance ( porta praetoria ), the road going from there connected the fort complex with the Stanegate. The north, east and west gates were uncovered between 1828 and 1935 and later preserved. The north and west gates were flanked by gate towers, which protruded relatively far from the wall, a structural feature that could often be observed in forts of the late principate . In contrast to the ramparts, the gates in Vindolanda did not have double passages, although they were structurally very similar. They represent a type of building that was completely out of date by the time it was built, in the middle of the 3rd century. The east and south gates of Fort IX were only small and had no guard rooms. Perhaps they only served as side gates or hatches .

North gate: The flank towers measured 6.6 × 4.9 meters and protruded slightly over the fort wall, the passage was 3.6 meters wide. The entrances to the towers were on the southeast corner. It was probably built in the early 3rd century, its building material still comes from stone fort VII.

West gate: At its flank towers are u. a. the stone thresholds of the entrance doors can still be seen. The two towers were apparently added a little later. The passage was 2.9 meters wide, the tower foundations are made of large stone blocks, the southern one measured 2.82 × 2.6 meters. Its construction was similar to the side gates ( porta quintanae ) of the ramparts Benwell , Chesters and Birdoswald . The street starting from the gate ( Porta principalis sinistra ) crossed the Vicus II .

Osttor: In an early construction phase it was also reinforced with two flank towers, as corresponding foundations were observed on both sides of the passage. There was no road outside, just a stone staircase leading away from the gate.

South gate: its remains are only visible as a slight elevation. The gate was partially exposed by Robin Birley in 1969. It was also very simply constructed and had no side turrets. On the east side there was still the pivot hole for the pivot of the wooden gate. The passage was 4.35 meters long and 4 meters wide. The wall cheeks were only 0.85 meters wide. Beyond the gate threshold there was still one or more stone steps that made it impassable for carts, probably to compensate for the height difference of 0.65 meters between the threshold and the road. Apparently it was walled up in the late period of the fort.

Enclosure

The fort wall was excavated and consolidated on the north and east sides as well as on the west side between the north-west corner and the west gate. Elsewhere, their position is only recognizable as an elevation on the edge of the fort platform. Some of the walls are still up to three meters high. They consisted of a quarry stone core, encased on the front and back with cut sandstone blocks, which were connected with lime mortar. The surrounding wall was additionally supported by a rear earth ramp made of clay, which also served as a battlement. This could be reached via a gravel road ( Via Sagularis ) that ran around the entire camp . When it was discovered in 1972, the wall on the NE corner was still nine rows high (91-122 cm). It had been repaired several times or rebuilt in some places. Several drainage channels ( culverts ) were built through the wall to drain the seepage water from the interior . On the inside of the fort wall, four gun platforms were also encountered. The core of the platform at the northwest corner consisted of stone rubble and clay which was bordered with several layers of stone blocks. The ballista set up here covered the north gate of the fortress.

Trench system

The moat surrounding the fort could be cut on its west side between 1969 and 1972. It was 4.90 to 6.10 meters wide, its slope, secured with stone packings, was made somewhat steeper on the side facing the fort. Part of the stumps of the previous wood and earth forts still protruded from it. Overall, its course turned out to be quite irregular. At the end of the 4th century it was apparently only used as a drainage system for rainwater drainage and as a garbage dump.

Interior development

The fort had the standard interior buildings for auxiliary troop camps during the Middle Imperial period. They were almost entirely made of stone: in the center an administration building ( principia ), two granaries ( horrea ), team barracks ( centuria ), workshops ( fabrica ) and a latrine ( latrina ). The north wall stands over the foundation walls of four circular huts from the Severan period. These have been preserved and are visible. Another three of these structures are known from the excavations from 1934 to 1936 and 1979 to 1980 and were filled in again. Stone buildings belonging to Castle VII including its principia have been excavated, but only two of its walls, running in a north-south direction, are still visible. In the middle of the third century a double barrack was built in the north-eastern corner of the camp, possibly to accommodate cavalrymen. The building was rebuilt several times and was occupied until around 400. During excavations in 1980, the remains of the east-west facing crew barracks were uncovered, but after their investigation they were filled in again. After the vicus was abandoned around 270, the remaining population was resettled in the fort. Some of the barracks had to be demolished for this. Subsequently, 20 new residential buildings were built on these grounds, including shops, houses with small backyards and workshops that were inhabited for a long time after the end of the Roman occupation. In one of the buildings an inscription was found that revealed the name of a man, Riacus, possibly one of the post-Roman residents of the fort, who lived there in the 5th or 6th centuries.

Principia

The still visible remains of the multi-phase principia (camp administration) date from the 4th century (construction phase II, stone fort IX) and faced north, towards Stanegatestrasse. The 24.8 (east-west) × 26.6 meters (north-south) foundation walls were completely exposed and preserved. They overlay the remains of the original command building (construction period I), which was also built of stone, but whose axis was oriented more towards the south. It was built using the Adope method, typical of buildings in North Africa and Spain. A relief of the sun god on his chariot and a few small statuettes were recovered from it. The additions to construction phase III, which were made after 367, were completely removed during the excavations. The building could be entered on the north side through the main entrance. There was also a portico on the street side , similar to that of African forts. This was later walled up and converted into storage rooms. The inner courtyard was relatively small and not, as in most buildings of this type, surrounded by a portico on the sides, but by closed rooms. They probably served as armories ( armamentaria ). Across the courtyard one entered the transverse hall ( basilica ) through a small narthex . There the tribunal can still be seen in the east together with two preserved steps. Five chambers were added to the rear of the transverse hall. The door openings of the two outer doors were only 90 cm wide, the three middle ones had portals vaulted with arches, two of which were decorated with stone reliefs (rectangular patterns). They were intended for the camp administration as a writing room ( officium ), as well as the offices of the two standard bearers ( Signifer ) and adjutants of the camp commandant ( Cornicularis ). These chambers could be closed with iron bars. The larger, two-part square chamber in the center served the imperial cult ( Aedes ) and as a flag sanctuary ( Sacellum ). The garrison's pay was deposited under the flag shrine. In Vindolandas Principia, however, there was no brick cellar room for this, but only a simple pit, protruding about three meters to the south, solidly set in stone. In the 4th century two of the chambers were equipped with underfloor heating and the western one with a small latrine. After 367, the two armories were apparently used as storage rooms (with slightly raised floors and vents) for food. In the inner courtyard, a 6 meter deep well was excavated to supply fresh water. The roof of the basilica was also supported with pillars. The administration rooms were converted for residential purposes and provided with underfloor heating. An open fireplace had been set up in the flag shrine for a long period of time.

Praetorium

East of the Principia, in the central area of the fort, was the camp commandant's house ( praetorium ). The remains visible today date from the 4th century. On its outer wall, Hedley found three consecration altars, donated by commanders of the fourth Gaul cohort, now in the Chesters Museum. The heavily damaged building complex was very difficult to interpret. It was essentially a 650 m² peristyle house with 18 rooms, which were grouped around an inner courtyard. There was probably another storage room on the east side of the building. It was built in the 210s and significantly changed around 300, including the addition of hypocaust underfloor heating in some rooms and the gradual construction of the inner courtyard, where additional rooms and corridors were added. At the eastern end there was a bathhouse with hypocaust heating, a water basin and an apse. In post-Roman times, the south and east wings were torn down, and a building from the 4th century, possibly used as a church, with an apse and east-west orientation was built in the inner courtyard. The excavations have shown that the visible remains are by no means the oldest. A small section of a wall from an earlier row of buildings can still be seen on a layer below. Overall, the building was of a very high standard, as the still-preserved door sills prove. It is also noteworthy that at the eastern end of the bathhouse on its outer wall an elaborately designed base can be seen, which must have been created when the main house was expanded, as this wing of the building overlaps the internal Wallstrasse.

Warehouses

Immediately to the west of the staff building was a double horreum for storing grain. The warehouses were built in the 3rd century. It was a type B building; H. free-standing inside the fort. One can still see part of the double floor made of stone slabs, it rested on brick air ducts that allowed the grain stored there to be ventilated. The western horreum was reinforced on the long side by six support pillars and on the narrow sides by two pillars. The raised floor in the western warehouse was removed when both were converted to residential buildings at the end of the 4th or early 5th century. A large amount of supplies was stored in the granaries of the fortress, which the garrison could keep alive for many months in the event of a crisis.

workshops

A building discovered on Via praetoria leading to the north gate is interpreted as a workshop (fabrica) .

Crew quarters

The barracks in the northeast corner of Vindolanda corresponded to the scheme of the Middle Imperial period. They were double barracks with head structures for the officers, who stood back to back and were separated from the other barracks blocks by a street. The living rooms ( contubernia ) were divided into two rooms and about 35 m² in size. The front rooms had stoves or fireplaces for food preparation. In contrast to many other barracks of auxiliary troop forts, those in Vindolanda only had six instead of the usual eight living rooms. They were structurally separate from one another and only assembled back to back with those in the second block. This also applied to the head buildings, which were also free-standing. During the excavations, a barracks was also examined, which was used until the end of the 3rd century. Each contubernium there consisted of only one room. It is possible that these buildings were even two stories high, as the thickness of their walls suggests. Remnants of windows were found, along with stoves or fireplaces, which had somewhat increased the living comfort compared to the other fortresses in the Wallzone. The gable walls of the barracks were oriented towards the narrow sides of the fort.

Iupiter sanctuary

In the north-western area within the fort, near the walls of the north gate, a shrine for Jupiter Dolichenus was excavated in 2009 , in which, among other things, an altar stone was located. The sanctuary was built around 220 AD by order of the garrison commander at the time. A sacred building within an auxiliary fortress is extremely rare. It was destroyed around 370, possibly in the course of Christianization.

latrine