Coriosopitum

| Corbridge castles | |

|---|---|

| Alternative name |

a) Corstopitum, b) Coriosopitum , c) Corsopitum , d) Corsobetum , e) Coria , f) Corielopocarium |

| limes | Britain |

| section |

Stanegate , Hadrian's Wall |

| Dating (occupancy) | agricolanic / hadrianic , 1st to 5th century AD |

| Type |

a) Alen and cohort fort. b) Supply center |

| unit |

a) Legio II Augusta , b) Legio VI Victrix , c) Legio XX Valeria Victrix , d) Ala Gallorum Petriana e) Cohors I Vardullorum f) Cohors I Lingonum |

| size | Surface: |

| Construction |

a) Wood and earth fort. b) Stone fort |

| State of preservation | Square complex with rounded corners, two small forts with an irregular floor plan in the center of the civil town |

| place | Corbridge |

| Geographical location | 54 ° 58 '42.2 " N , 2 ° 1' 44.7" W |

| Previous | Fort Pons Aelius (Stanegatelinie) (northeast) |

| Subsequently | Newbrough Fort (Stanegate Line) (west) |

| Reconstruction of the city at the time of its greatest expansion around 225 AD |

|---|

| Peter Lorrimer |

|

Link to the picture |

| Aerial view of the excavation area |

|---|

|

Link to the picture |

Coriosopitum (or Coria ) was in the area of today's Parish Corbridge / Sandhoe, District Northeast, County Northumberland , England .

From the 1st to the 5th century AD, the place was one of the most important military bases and Roman cities on Hadrian's Wall . Most of the remains that are still visible today belong to the civil town at the intersection of Dere Street and Stanegate , which had developed around a fort and the Tynebrücke. A legionary base in the middle of the civil town later replaced the forts that were founded there in the 1st and 2nd centuries. After Hadrian's Wall was completed, it was converted into one of the supply bases for the garrisons in the eastern section of the wall. In the early 3rd century Coria played an important role again in the caledon campaigns of Septimius Severus . By the 4th century it had reached the size of a small town. Corbridge remained a vibrant commercial and military center until the final years of Roman rule over Britain. The archaeological site is now under the protection of English Heritage and has been made accessible to visitors. The most important finds include the components of Roman segment armor, with the help of which functional replicas could be made. The finds will be exhibited on site. The Corbridge Hoard artifacts are on display at the Corbridge Museum and the Great North Museum in Newcastle upon Tyne .

Surname

The ancient place name appears in the four most important written sources of ancient times:

- Itinerarium Antonini ( Corstopitum ),

- Geographica of Claudius Ptolemaeus ( Coria ),

- Vindolanda tablets ( Coria or Coris ),

- Geographer of Ravenna ( Corielopocarium ).

Further writing variants are:

- Corioritum ,

- Coriosopitum ,

- Corsopitum ,

- Corsobetum .

The current place name could still go back to the Roman Corstopitum . If so, Cor - must be an abbreviation of the original place name, in which only the first syllable was retained. The name probably comes from pre-Celtic times. Coria / Coris could have the same roots as the Gaelic Coire (= round depression / sinkhole ) and the Welsh Cwm (= valley). Both terms would go well with the topographical features of the Corbridge area. Corstopitum was possibly a combination of its old British name and the Latin strepitum (= loud, echoing). It could mean “the noisy (busy) valley”, a fitting term for a busy military and trading post on the northern border. Corie Lopocarium appears in the Ravenna cosmography of the 5th century - between Concangis (Chester-le-Street, Durham) and Segedunum (Wallsend, Tyne & Wear). In research it is equated with the Coria of Ptolemy. According to the entry there, the Romano-British city seems to have been known by its original name again from the 5th century. What the suffix Lopocarium means remains unclear. Either it is a copying error by the medieval copyists, or a separate settlement that has not yet been identified or located. Perhaps it also designates a settlement center of indigenous British, the Corionototae, in this case a branch of the brigands , the suffix could therefore contain their tribal names. J. Hind has suggested that the Roman name for the fort and town could actually have been Corioritum .

The Anglo-Saxons called the place Corchester , around 1050 there was a bridge again, Corebricg , to which the place name in use today largely goes back.

location

The forts and town were on the north bank of the river, 28 km west of Newcastle and about 800 meters west of Corbridge. In the Antonini Itinerarium of the late 2nd century, Iter I (Route) lists all road stations from Hadrian's Wall to the Praetorium ( Bridlington ) on the north-east coast of England. According to the second entry, Corstopitum was 20 Roman miles from Bremenium and 9 miles from Vindomora . Two milestones found at Corbridge came from the reigns of Victorinus (269-271) and Maximinus Daia (309-313).

Coriosopitum stood on a hill above the Tyne . This slopes slightly to the south to the river and to the west to the Cor Burn. It just runs out in the north. It was thus placed at the lowest geographical point in the river valley. Nearby the North and South Tyne merged. There Dere Street , at that time one of the most important north-south routes in Britain, crossed the river. She entered the city a little further west of the remains visible today. About 4 km to the north was the Portgate , a busy border crossing on Hadrian's Wall. In Coriosopitum the Dere Street met the Stanegate , which was used as an east-west connection between Pons Aelius and Luguvalium (Carlisle) and to supply the border garrisons. Anyone who wanted to get to the west coast, north or the wall quickly had to pass through the city.

The three main routes to Northern Great Britain were two north-south roads and the east-west Stranegate between Coria and Luguvalium (Carlisle). Of the two main roads running from north to south, the eastern one ran through Coria , the western one through Luguvalium . Dere Street ran east through the Pennines and split at Scotch Corner - north of Cataractonium (Catterick). It connected a number of the Pennines forts - including Vinovia (Binchester) - with Coria . The other road branched northwest, crossed the Pennines via Stainmore, Bowes, and Brough, and then ran northwest to Luguvalium and beyond. Alternatively, you could also travel on the west side of the Pennines from Deva (Chester) to the north via Bremetennacum (Ribchester) to Luguvalium . The modern highways in the north of England and in the south of Scotland, the A1, A68 and A66, still follow the routes of the former Roman roads in many places.

Road connections continued to exist over the Stanegate

and across Dere Street

- Onnum (Halton Chesters, Northumberland), copy after

- Vindomora (Ebchester, Durham), for

- Portgate , after

- Habitancum (Risingham, Northumberland),

- Bremenium (High Rochester) and maybe after

- Whitley Castle (Northumberland).

Research history

The antiquarians John Leland and William Camden visited Corbridge between 1539 and 1599 and saw erect Roman walls there. At the beginning of the 18th century, John Horsley described the site as largely destroyed by the plow. Alexander Gordon could still clearly see some wall structures. By 1810 the ruins were finally completely leveled by agricultural activity.

What is known about ancient Coria today only covers a small section of its total area. Between 1861 and 1862, William Coulson exposed the northern end of the Roman bridge and several other structures within the Roman city. The scientific investigations began in 1906 (Francis Haverfield, J. P. Bushe-Fox, Robert Forster). Foster led, together with the architect WH Knowles (Newcastle) from 1907 to 1914 the excavations in Corbridge. Between 1910 and 1911, part of the substructures of the granaries was provided with a layer of mortar for conservation. The central part of the ground monument came under state protection from 1933 on the initiative of David Cuthbert (Beaufront Castle), Robert Forster and Eric Birley and is now in the care of English Heritage . This area has been the subject of continuous research since 1914. From 1935 to 1936, Charles Anderson consolidated the horre walls and flagstone floor, as well as the columns and masonry at the southern end of the storage building. He came across numerous Roman coins in the ventilation ducts of the granaries. The forts of the 1st and 2nd centuries were explored in the 1940s and 1970s. Ian Richmond excavated Corbridge in the early years of World War II, but it was only after the war that a large series of excavations began that lasted until the early 1970s. In between, rescue excavations were always carried out, e.g. B. when the bypass road A69 was created and the local museum was set up. In 1951, John K. St. Joseph took aerial photographs of the excavation area. The bath house was discovered in the southeast of Red House Farm when a drainage system was being built between the silage pits and the Red House Burn in 1955. Excavations took place there between 1956 and 1957. The finds consisted of Sami ceramics and roughly executed ceramics from the late 1st century, several bronze brooches and a coin from Vespasian . Brian Dobson conducted excavations in Corbridge in the 1960s and 1970s. The Agricolan fort was discovered in 1974 when the A69 bypass was built. The excavations were carried out by the Society of Antiquaries of Newcastle in advance of construction. During excavations in 1980 - west of the granary - the western wall of the Agricolan fortress was found. A 1988 report by Michael Bishop and John Dore on the excavations in Corbridge in the years 1947–1980 also describes the development of the two wood-earth forts.

Find spectrum

With around 34,000 artefacts, the archaeological collection in the Corbridge Museum is by far the largest of Roman everyday objects from the Wallzone. The material excavated between 1906 and 1914 and 1934 and 1973 came from e.g. Partly from distant provinces of the empire and offered insights into many activities and aspects of Roman life in Corbridge. It contains numerous sculptures, inscriptions, ceramics, military equipment, Roman tools, glass vessels, animal bones (wild and domesticated) and a bronze jug discovered in 1911, filled with 160 gold coins from the period between 64 and 160. The inscriptions are deities from the entire Roman Empire dedicated. Evidence of the prosperity of the Roman Corbridge is also provided by personal items found there, such as B. hairpins and artfully executed combs. Other finds indicate extensive ceramic and metal processing.

Corbridge hoard

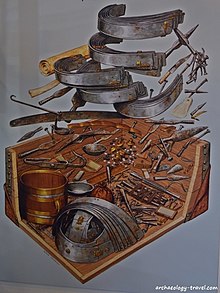

| Artifact (belt rails) from the Corbridge hoard |

|---|

| Great North Museum (Hancock Museum) in Newcastle upon Tyne. |

|

Link to the picture |

This deposit - still very well preserved when it was found in the Macellum in 1964 under the floor of a wooden building from the Flavian era by archaeologists from Durham / Newcastle University - consisted of the inventory of a carpenter's workshop and the equipment of Roman soldiers. These include rails of segment armor (so-called Lorica Segmentata ), a small wooden jug, wax writing boards, game boards and - unique for Roman Britain - the remains of papyrus rolls. The remains of feathers were also found in it, possibly from a pillow filling or helmet bushes. The sand and gravel deposits found in the Corbridge river terrace are usually not conducive to the conservation of ferrous material. In this case, however, they allowed the box and its contents to be fossilized . This means that mineralization occurred over time, during which the structures of the organic components were replaced by minerals washed out of the corrosive metals. The stratigraphy of the find showed that the chest had come into the earth towards the end of the second or third occupation phase (122-138 AD) and therefore probably belongs to Hadrianic times. It is believed that the equipment contained therein, especially the weapons, was intended for repair and subsequent reuse. When the fort was temporarily abandoned, it was probably easier to bury them to prevent them from falling into the wrong hands. This practice has been observed at many Limes locations.

chest

A material analysis showed that the chest was made of alder wood, a type of tree that normally thrives in wetlands and was mainly found on river banks. It was 0.88 meters long and 0.58 meters wide and about 0.41 meters high. The chest had a hinged, lockable lid and was reinforced at the corners with iron straps. A toothing was carefully sawn into the corners of the boards of the chest, which gave it a special stability and durability. It was then additionally covered with a leather cover to protect it from moisture.

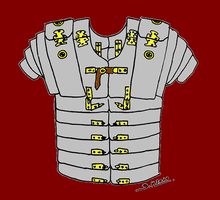

Segment armor

Six upper and six lower half units of so-called “Lorica Segmentata armor” were stored in the chest - once wrapped in cloths - which, although not entirely identical, had been used for three complete or partial sets of twelve other armor sets. The segments were thoroughly examined and interpreted. They enabled Charles Daniels and Henry Russell Robinson to understand how these tanks were constructed. It concerned the components of the shoulder parts, chest and upper back parts and belt rails, which came from two differently constructed sets (type Corbridge A and B). They are likely to have been in use until the 1st half of the 2nd century. The rails were made of sheet iron, while the locks were made of non-ferrous metal. A total of 40 pieces were recovered. The collar and shoulder sections comprised 24 splints, the belt section 16 pieces. In collaboration with Robinson, a trained armourer (Tower of London Armories), a detailed reconstruction of the Type A armor was made later. Every current replica of a Lorica Segmentata (this name comes from antiquarians from the 16th century) is based on their findings.

The type A rails were held together by elaborate lacing, on the inside and on the chest with leather straps, the rest - front and back - with leather straps. The closures and eyelets were made of thin brass. The contact points with the iron plate were very susceptible to corrosion. The eight belt rails were attached to the upper parts with leather straps and buckles. The chest and upper back rails were also held together by straps and buckles, while those on the chest and shoulder were held together by hinges. Leather straps were also riveted onto the narrower rails for the upper back, shoulders and hips for attachment. These tanks were therefore relatively time-consuming to put on and required a second man to knot the rear belt buckles and cords. Another major weakness of these versions was that the hinges and buckles could easily break when hit and therefore required constant maintenance and repair. In addition, the leather straps were very sensitive to moisture. Some of the armor must have been repaired several times. A broken hinge was e.g. B. simply riveted together.

According to Robinson, type B had a slightly larger breast plate and only seven instead of eight belt rails. In this example, the belts and cords of the belt rails have been replaced by hooks and eyes that are easier and, above all, quicker to close. The greater width of the chest plate (7.7 cm type A, 9.4 cm type B) allowed for better protection of the chest, although it did not attach satisfactorily to the neck area. It was not until the Newstead type that the buckles, hinges and cords were almost completely left out.

weapons

The chest contained several bundles of spearheads tied with string. Some of them still contained the fragments of their wooden shafts. Presumably they were broken off in battle and should be equipped with new shafts. Subsequently, a few bolts from a ballista and fragments of a sword scabbard were found.

Tools

Tools that could be recovered were a saw, pulley block, pickaxe, a fragment of a shovel blade (interpretation uncertain), a lamp holder, a chisel, a crowbar, scissors and a knife, along with a large number of nails and other carpentry accessories. Presumably they all come from a workshop.

development

Pre-Roman times

The region around Corbridge should have been populated since the late Bronze or early Iron Age. Among other things, the archaeologists found traces of a circular palisade fortification with a west gate, which was typical for this period . A passage in the Geographica of Claudius Ptolemaeus (early 2nd century) reports that the " Otalini / Otadini " are said to have been resident in Alauna , Bremenium and Coria . These could be located on the west coast of Cumbria, Learchild and High Rochester and Corbridge. This tribe was in truth the Votadini , whose territory included the north-east of England, in what is now the county of Northumberland and the border region with Scotland. The place possibly served as a local tribal center, a Roman altar inscription mentions the people of the Corionototae . This tribe then probably settled in the immediate vicinity of the fort. Her name could have the same roots as Corbridge's Roman name.

1st century AD

Corbridge developed into one of the two most important supply and trading centers on the northern border of Britain. Like Arbeia , Luguvalium and Portus Trucculensis , it was close to Hadrian's Wall, but it was not part of its chain of fortresses. The earliest Roman fortifications were probably built during the second campaign of Gnaeus Iulius Agricola . He founded a fort there between 79 and 80 AD, which was probably used to supply and gather his troops before he advanced with them to the northernmost edge of the British Isles. The excavation site was clearly classified as a fortress or arsenal that housed legionnaires and auxiliary troops and secured a bridgehead on the Tyne. It is believed that it was the main eastern base of Agricola's expeditionary army. Around the year 90 the supply base was closed and a small camp village began to emerge south of the auxiliary fort.

2nd century AD

The camp was burned down at the beginning of the 2nd century. After that, a new fort was built at the same place to secure the new border line (" Stanegate "). It was expanded by 122 to accommodate nearly 1,000 men to support the garrisons and construction crews on Hadrian's Wall , construction of which began that same year. There are indications that in Coria - during the reign of Hadrian - there was an occupying force of legionnaires who were primarily supposed to guard the strategically important Tyne Bridge when the wall was being built. Between 125 and 140 the fort was probably empty. In the course of time, however, the civil settlement rose to become a regionally important trading and logistics center and remained so in Britain until the end of Roman times. When the Romans invaded Scotland again in 140, a force consisting of cavalry and infantry was moved to Corbridge as a garrison. During the tenure of the governor, Quintus Lollius Urbicus , the Legio II Augusta had apparently been entrusted with larger construction projects there. When Urbicus wanted to subjugate the northern region in a campaign, this seems to have had its starting point in Corbridge. Corbridge was the scene of extensive activities, especially in the years between 139 and 140, the time when Hadrian's Wall was temporarily abandoned and the imperial border was brought forward to the Antoninus Wall under Emperor Antoninus Pius (138-161) . Some inscriptions found on site testify that several buildings, including probably the two warehouses, were erected at the time. The traces of these previous buildings were observed under the remains of the large granaries that are still visible today. These construction measures are probably related to the main function of the place as a supply center and strategically important base on Dere Street. It is attested by an inscription in which the governor Sextus Calpurnius Agricola is mentioned, who took office around the year 162. All of this probably in the course of the reoccupation of Hadrian's Wall and some of the old Stanegate camps after the border army withdrew from Antonine Wall. Around 163 the Stanegate fort was replaced by two small fort, in each of which a vexillation legionnaires was stationed.

3rd century AD

In the early 3rd century, Emperor Septimius Severus also stabilized the northern border against the Picts , and Corbridge became a legionary base again. Inscriptions prove that these divisions were assigned by the legions stationed in Britain. Only under his reign (193–211) did the buildings still visible on the site begin to take on their final shape. The location was now one of the two main supply bases for the campaign of 208. By this time at the latest, an extensive civil town had developed around the forts and supply depots. Presumably, it was also the administrative center of a largely autonomous civitas (like Luguvalium in the western sector of the wall). The last inscription from Corbridge (the building inscription of one of the storehouses) mentions the governor Lucius Alfenus Senecio . He administered Britain from 205 to 208 and was the last known governor to preside over all of Britain before it was divided into two provinces by Severus. According to the inscriptions, Coria was also visited by merchants from distant provinces of the eastern Mediterranean and Asia Minor. The two large granaries in particular underscore Corbridge's role as a regional market center and one of the supply bases for the fortresses of Hadrian's Wall.

4th to 5th century AD

In the troubled 4th century Coria was probably surrounded by a wall. There were probably also soldiers from the regular army stationed there, but the name and serial number of the late antique garrison have remained unknown. Coria is no longer mentioned in the Notitia Dignitatum ( Dux Britanniarum troop list ) . The last major repair work, probably ordered by the late antique military administration, was carried out around 370 on the main road. The Roman rule in Northern Britain ended at the latest in the year 410. The city seems to have been abandoned by most of the Romano-British inhabitants soon afterwards. Some of them may have stayed there until the late 5th century.

Post Roman time

From the 7th century an Anglo-Saxon settlement developed in Corbridge , which spread not far east of the ruins of the Roman city. At that time the Roman bridge was no longer passable, but its ruins probably still dominated the landscape. The ruins of Coria were exposed to massive destruction, especially from the 670s . With the stone material obtained in this way, u. a. the Church of St. Wilfrid was built in Hexham, 3 miles away. The stone robbery probably lasted for several centuries, because in the end the city and bridge had almost completely disappeared. Large quantities of Roman stones have also been found in the early medieval (Anglo-Saxon) building fabric of St. Andrew in Corbridge. King Johann (1199–1216) had the Roman ruins ransacked for treasures at the beginning of the 13th century. The workers found only stones and “brass, iron and lead”, a reference to the special Roman construction technique that could be observed at the well or the bridge: the stone blocks were connected with metal clips instead of mortar.

Castles

The forts of the 1st and 2nd centuries lie largely under the remains of the later legionary base and the civil town. Most of the auxiliary troop camps on Hadrian's Wall face north, with the exception of Housesteads , which had to be oriented east because of the steep terrain ridge. The main axes of the Corbridge camps, however, faced south. This peculiarity could also be observed in the second fortified city of the Wallzone, in Carlisle . The post-war excavations focused on the Macellum to try to reconstruct the sequence of what is believed to be four phases of the fort.

- Phase I (approx. 86-105)

- Phase II (approx. 105–122)

- Phase III (approx. 122-139)

- Phase IV (approx. 139–163)

Red House Fort

The first Roman fortification stood about a kilometer west of Corbridge, on the grazing grounds of Red House Farm. Nothing can be seen of this fort today, its few remains that were uncovered during emergency excavations were filled in again after their investigation and are now overlaid by a trunk road (A69). The wood-earth construction was founded between 70 and 84 AD and soon after, after some structural changes, it was apparently destroyed by fire around 105 and abandoned, perhaps also because of its constant danger from flooding. There are indications that the defenses and the inner buildings were demolished and that the area was then only used for agriculture.

Little is known about its appearance. Presumably it had a rectangular floor plan with rounded corners (playing card shape), typical for the forts of this time period. According to estimates, it covered an area of about 2.8 hectares. During their excavations in 1980 south of Red House Farm u. a. of the eastern and western defensive trenches and a presumed intermediate tower. The rampart was rebuilt several times before it was partially leveled (after 160). The eastern trench was separated from its western counterpart by a gap about 257 meters long. The actual dimensions of the Agricolan camp, particularly its extent to the north and south, are uncertain. The northern part of the fort area is partly built over by farm buildings. The southern part is occupied by dirt roads and field walls.

Post holes of several wooden buildings have been found in the interior, possibly including a well shaft. One of the buildings could be identified beyond doubt as a barracks block. Furthermore, a dozen of a kind of open storage shed (dimensions approx. 17.5 × 7 meters) should have stood there. The workshop and some of the storage sheds to the east went through at least two construction phases.

Stanegate Fort

A coin of Trajan, which was discovered under the fort wall, dated from the years between 103 and 105. It is assumed that the approximately 2.5 hectare fort was founded during this time. At that time, Emperor Trajan withdrew troops from Britain for his second Dacian campaign. It was erected directly above the leveled Acricolan camps and abandoned for a short time under Hadrian . Presumably this happened during the completion and manning of Hadrian's Wall (122–125 AD). In 139 it was again occupied with auxiliary troops, probably in support of Lollius Urbicus' campaign to the north. Further changes to the interior were made around 155, with some wooden buildings being replaced by stone structures. A fragment of an inscription from the years 155–158 documents the date of this construction work, which was probably necessary to adapt the camp for a new crew, probably withdrawn from Scotland. By 160 all wooden buildings (but not its ramparts) had been replaced by stone structures. In 163 it was given up again. The foundations of the camp headquarters and those of the commandant's house ( praetorium ) are visible today within the macellum .

The Principia went through several construction phases:

- Phase Ia, Flavian wooden building,

- Phase Ib, no major changes from la, demolition of the building,

- Phase II, erection of a smaller wooden building,

- Phase III, partial reconstruction of the Phase II building,

- Phase IVa, reconstruction in stone with a few small changes, but possibly only stone foundations were laid,

- Phase IVb, rising masonry of poor quality, then abandonment of the building, the flag shrine was probably used as a material store during the construction of the macellum .

A number of construction phases could also be distinguished for the Praetorium:

- Phase Ia, wooden building and granary,

- Phase Ib, the wooden building is partially rebuilt; Erection of a new building south of both, then deliberate demolition of the old structures,

- Phase II, smaller warehouse building with a similar building south of it,

- Phase III, construction of two wooden granaries in the north, buildings of unknown use in the south,

- Phase IVa, wooden vestibule with south wing,

- Phase IVa / b, elevator of five north-south stone walls, probably the substructures of a granary; later replaced by four shorter east-west walls,

- Phase IVb, sewer is filled with rubble; Remodeling in stone.

After the Stanegate fort has been abandoned, the praetorium will be demolished and its area leveled.

Bathhouse

The excavations in the 1950s revealed the remains of the approximately 49 × 43 meter large storage bath ( Ballineum) . When they were uncovered, the walls were partially preserved up to a height of 1.33 meters. The arrangement of the rooms made it possible to identify the building as a row type, which was widespread in the empire. The unusual position of the peristyle in these buildings was striking . The finds found there suggest that it was built around 80, but was dismantled before 98 - apparently according to plan. In order to preserve its remains for future research, they were filled in again after the excavations. According to a report in the Daily Telegraph of March 30, 1972, they were destroyed - despite a Preservation Order from the Department of Environments - at the instigation of the landlord of Beaufront Castle (Hexham).

Legion quarters

These military buildings (east and west complex) located in the center of the civil town comprised barracks, temples and a warehouse headquarters with a basement. The groups of buildings surrounded by a stone wall apparently housed the legionary vexillations stationed there, as suggested by inscriptions from the Legio II Augusta found in the principia of the west fort. They should also be used by members of the II. And VI. Legion have been built. The two complexes were built over the remains of a leveled layer of fire and are therefore of a later date than the Macellum . They may be from the late 2nd or early 3rd century. Their floor plans were irregular, the walls and gates more decorative, which suggests that their main function was to spatially separate the soldiers' quarters from the civil town. Their eastern and western fencing was based on the boundaries of the temple precinct. Today's museum building stands directly above the western fort defenses. The foundations of the eastern fort wall are easy to follow. In their early phase, both military complexes were surrounded by separate walls and their gates were opposite a road that branched off from Stanegate and headed south. Much of the fence was later demolished and the two complexes merged into one. The principia of the west fort was set up as a joint headquarters, the main gate of the complex was now in the south. Probably this happened in the late 3rd or early 4th century.

East fort

The remains of the east fort, which are still visible today, belong to the fortifications, the principia, the apse of the flag sanctuary ( Aedes ) and the officers' quarters. A small rectangular building was as a latrine ( Latrina be identified). On both sides of the sanctuary there were a number of smaller rooms, probably the office of the camp administration ( Officia) . To the west of it stood a transverse hall ( basilica ). However, the camp headquarters did not have an inner courtyard, an architectural feature best known from the Principias built in the eastern part of the empire. It could be related to the participation of Romano-British troops in campaigns in the east during the 2nd century. Another apsidal wall structure of unknown function is located in the southeast corner of the fort. Starting from the Principia, a street led to the east gate, the main street ( Via Prätoria ) of the camp. The wall to the west of the camp headquarters belonged to a larger rectangular building that the excavators identified as a workshop ( Fabrica ). Another building may have served as a kind of grocer's shop or tavern ( tabernae ). An even larger building structure could originally have belonged to two separate officers' quarters, which were probably very similar to the tribune houses in the legionary camps, but were much smaller in area. In one of these buildings there was a pottery kiln, but it probably came from a much later construction phase. At the western end of the fort, the remains of the western gate can still be seen.

West fort

The entrance gate of the western complex is parallel to its counterpart in the eastern fort. Immediately to the north of it was an apse building. Its function is unknown. Perhaps a meeting area ( schola ) for officers and batches. The apse stood at its western end, the entrance was on the east. In front of it there was a small portico consisting of four columns on the street side. Since the discovery of a dolichenum in Vindolanda , however, it has been known that temples were also built inside forts, perhaps the building was such a sanctuary. During the 1912 excavations, a number of canals were observed under its floor. Before the First World War, wall structures of the interior buildings were excavated at the main gate. These buildings may have originally served as team barracks and horse stables. They were oriented from north to south, had head buildings (centurion quarters?) At both ends and back to back in pairs. Richmond and Birley referred to them as workshops I to IV (numbered from the east) because a large number of metal fragments were found inside, including numerous arrow and pilum points. Presumably they were used as blacksmiths in a later period. At the southern end of the western barracks there was a water reservoir made of stone slabs, in which the rainwater that ran off the roof was collected. The spaces between its plate segments had been sealed with lead. Like its eastern counterpart, the Principia did not have an inner courtyard, but only a transverse hall and three office rooms in the north wing of the building. In the apse of the flag shrine, a steep staircase with narrow steps leads to a small cellar room ( aerarium ), in which the troop treasury was probably kept. As with the Principia in Chesters , it was originally covered with a stone vault. The walls on either side of the entrance are made of two large stone slabs. The floor is also covered with stone slabs. During the excavations, a broken inscription was found there, dedicated to the discipline of the emperors ( discipulina Augustorum ). In the north wing of the Principia, a small bathroom was apparently installed later.

garrison

Coriosopitum was probably occupied by regular Roman soldiers from the 1st to the late 4th century. During its existence it housed several vexillations that were drawn out by the Roman legions or auxiliary units permanently stationed in Britain. According to the Vindolanda tablets , some of the Centuries of the Cohors I Tungrorum from Vindolanda stayed there at times . In an emergency, the legionaries should strengthen and support the garrisons of Hadrian's Wall, including in particular the outposts that secured Dere Street as far as Newstead-on-Tweed (at least up to 180). Some of them were probably also used in warehouse management and market supervision. The presence of these units is known from inscriptions on tombstones and altars. Of some - presumably - soldiers or veterans stationed there, only the names or functions are known. Such as B. that of the Vexillarius (standard bearer) [. .] rathes of Palmyra or Quintus Calpurnius Concessinius, an Alen prefect who had killed members of the Corionototae tribe in battle.

The following units either provided the crew of Corbridge forts or may have been there for a limited time:

| Time position | Troop name | description | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2nd century AD |

Legio secunda Augusta

("The second legion of Augustus") |

Soldiers of this unit, especially their third and fourth cohorts, were stationed in Coriosopitum between 138 and 144 AD under the governor Quintus Lollius Urbicus . The Legion is mentioned on 11, recovered in the Corbridge area, inscriptions. They include building inscriptions (slab or centurial stones), which name those cohorts that were used to build the defenses and various buildings, inscriptions that provided valuable dating information, altars dedicated to the classical gods and the tombstone of one of theirs - although not named - Soldiers. | |||

| 2nd to 3rd century AD |

Legio sextae Victrix Pia Fidelis

("The sixth legion, the victorious, loyal and faithful") |

One of their vexillations was at the change from the second to the third century in Corbridge. She is mentioned there on a dozen inscriptions. The legionaries donated a. the Concordia an altar, the Roman goddess of peace and unity. Possibly it happened between the soldiers of the VI. and XX. again and again to friction. On the inscriptions are two simple soldiers

and some of their commanding officers by name.

From the governors in office at the time, the legates are:

mentioned in the inscriptions. |

|||

| 2nd century AD | Legio vicesimae Valeria Victrix ("the twentieth Valerian legion, the victorious") | The soldiers of the Sixth were reinforced for a short time by a contingent of the Legio XX under the governor Sextus Calpurnius Agricola . It is mentioned on a total of five inscriptions from Corbridge. It appears that cohort strength vexillation was used there for construction work during the second half of the second century. The only altar stone that could be assigned to the twentieth was dedicated to the goddess of concord, Concordia (see above). | |||

| 2nd century AD? | Ala Gallorum Petriana ("the Gallic squadron of Petra") | The Red House Fort was probably occupied by this 1,000-strong cavalry unit. Two headstones were found in Hexham Abbey and St. Andrews Church. One was placed between 80 and 98 AD for Flavinus, standard bearer in the turma of Candidus, the other for a rider whose name was unknown. | |||

| 2nd century AD |

Cohors Primae Vardullorum milliaria equitata civium Romanorum

("The first partially mounted cohort of the Vardulli, 1000 strong, Roman citizens") |

The cohort is attested by only one consecration stone from Corbridge. She was originally recruited from the tribe of the Vardulli who settled the province of Hispania Tarraconensis , in particular the present-day Guipuscoa region in northern Spain. The cohort is attested from other forts in the north of Britain. The Corbridge Altar was donated to the Emperor's Disciplina by one of its tribunes, Publius Calpurnius Victor. | |||

| 2nd century AD |

Cohors Primae Lingonum [equitata]

("The first partially mounted cohort of the Lingons") |

The unit was formed from members of the Lingon tribe. He settled in the province of Gallia Lugdunensis , in what is now Bourgogne in central France. The cohort is only mentioned in a single undated inscription from Corbridge, although the serial number is missing. |

Civil city

The archaeological park covers an area of 1.8 hectares and provides an insight into the core of the former Roman city, which was concentrated around two small forts for the legionary garrison and the Stanegate. The Roman buildings were almost completely demolished over the centuries by stone robbery and agricultural activity. The position of their foundations are mostly known from aerial photographs taken before the First World War and from excavations carried out in the 20th century and extend over about 15-20 hectares. In 1951, Kenneth Sinclar St. Joseph described the remains of the civil settlement as follows:

“In Corbridge, traces of streets and buildings have been found in a wide area around the visible excavations. The main street (Stanegate), which is opposite the two military complexes, runs in an irregular course to the east and west and was flanked on both sides by a stone drainage channel. The side streets branch north and south ”.

May have been Coriosopitum conceded at the beginning of the third century, the self-government. Its area probably extended over 25 hectares. Its development is dominated by strip houses, which along the street fronts are more reminiscent of the military barracks than of the buildings in the south-eastern small towns of Britain. A very rudimentary street grid surrounded the core of the military area. Presumably the civil settlement was also fortified by a wall and ditches. Further aerial photos from 2006 again showed very clearly the streets and wall structures of the vicus in the fields to the west of the forts and, to a lesser extent, to the north and east of them. Numerous pits were visible on the photographs, but it is not certain whether they also came from Roman times. The pits were possibly created during the extraction of building material or could also have been used for garbage disposal. Due to the constant presence of legionnaires, it was probably equipped with a much better infrastructure than that of most of the other civil settlements on Hadrian's Wall. Its undulating terrain is also remarkable. It was probably caused by the steady subsidence of the ground after the Roman settlement phase. Presumably the Romans built it over a drained bog. As a result, the floor plans of the ancient buildings cannot be fully recognized from the ground.

The main street, the remains of which date from the 3rd and 4th centuries, separates the fountain house and the granary on the north side from the two small forts in the south. Between the two small forts there is another road that runs from north to south. It coincides with the line of Via Praetoria of the Stanegatekastell. If you look to the north you can still see the remains of his flag sanctuary. The intersection between this street and Stanegate was right in the center of ancient Coria . The museum building and the strip houses at the eastern end of Stanegatestrasse are located directly above the ramparts of the Trajan castle.

Warehouses

The two granaries ( Horrea ) facing north-east to south-west , the substructures of which most likely date from the early 3rd century AD, are the best-preserved specimens in Great Britain and were located north of Stanegate. Presumably they were built in the early 2nd century, abandoned in between and then completed a little later (probably at the beginning of the 3rd century). On the south side of the granary stood four stone pillars of a portico that extended far out to protect the loading ramps from the weather. Their bases had been completely filled in by the steady rise in the level of the street banquet in the 3rd and 4th centuries. You can still see the bases of the walls and supporting pillars, the double floors and underground channels that have remained largely intact. The floors, made of solid stone slabs, rest on low stone walls with channels between them. These channels ensured that fresh air could circulate under the ground and that the grain stored above remained dry. The underground channels were connected with stone pillars divided openings in the outer walls. At the eastern granary one of these stone pillars can still be seen on a ventilation slot in situ (east side), the only one in Great Britain that has survived the centuries unscathed. The outer walls were reinforced by 19 square pillars each. In the west and north, the granaries were angularly surrounded by a low wall. One of the granaries was last renovated or completed by legionaries during the Severan campaigns between 198 and 209, according to an inscription found on the southwest tower of Hexham Abbey. In the western warehouse building, a building inscription from the Legio II that was used as a floor slab was discovered.

Strip house

To the northeast of the granary, right next to the aqueduct, was a rectangular building, a so-called strip house . Apart from the fact that a forty-eight gold coin hoard from the late 4th century was found there in 1908, it was of no great archaeological significance. Probably the hoard came into the ground around 383.

Macellum

The foundations, which are still visible today, belonged to an extensive, 67 × 65.5 meter square building structure with an inner courtyard (so-called building 11). After it was uncovered, archaeologists disagreed about its interpretation for a long time. Haverfield thought it was some sort of legionnaire's barracks, while Forster advocated a forum . Presumably it was actually built as a warehouse and macellum (market place). The Macellum Magnum built by Emperor Nero in Rome could have served as a model . It was right on the Stanegate. Its construction probably began in the late 2nd century. The reassessment of the finds made there from excavations in the 20th century suggest that its foundation stone was laid between 160 and 185. It was destroyed by fire soon after, but was still unfinished at the time. Some researchers believe this happened during a barbarian invasion in the early 180s. Its masonry is of a high quality craftsmanship. The building was built from massive, closely spaced blocks with no mortar connection. The blocks have prominent protrusions, as we know them from Greek and Roman buildings in the Mediterranean. The edges of the blocks in particular had been carefully machined and sanded. Only the street front and part of the side wings of the building were completed (west and south wings). The northern foundations were laid out very flat. Its southern rooms would later be converted into small shops, the fronts of which were open to the main street. The wide entrances to the rooms also indicate that goods were stored and sold there. It was essentially a peristyle house with a water basin in the courtyard. The latter was decorated with a group of statues (now on display in the Corbridge Museum). The sculpture depicts a lion killing a roebuck. Presumably it originally served as a grave ornament.

Pottery workshop

In 1906, wall structures and large quantities of ceramic fragments were found in the southwest corner of the excavation site. Presumably the building served as a pottery workshop or shop.

Fountain

The well house was the main distributor of fresh water in the city. Between the macellum and the granaries, a stone water pipe ( aqueduct ) leads to a public fountain on Stanegate. The building was another important step from the development from a pure military base to a city. It was probably created shortly after the wood and earth forts were leveled. The aqueduct ran from a higher terrain in the north (Cor Burn) - directly through the former bath house of the fort - into the center of Coria . It was built by the Legio XX Valeria Victrix who noted this in a building inscription. It consisted of a small Fortuna shrine , a gable-shaped gargoyle and two stepped water basins, flanked by two statue platforms. In the upper part of the system, it first flowed through an ornamental pour opening that was supposed to aerate and purify the water. Then it flowed into a sedimentation basin, which then in turn filled a lower basin, from which one could then draw the clean water. The system was drained through a canal that ran to the south next to the granaries. The edges of the lower water trough have deep grooves, perhaps not only from the sharpening of blades, but also from centuries of civil use.

Temple precinct

The cult district of Corstopitum , divided into two areas (west, east), was located to the northwest and northeast of the two military complexes . All cult buildings discovered there so far seem to have been street temples built in the classical Roman style. In the eastern enclave there were at least five such cult buildings (1–5), in the western enclave two (6–7). However, the altar stones and religious artefacts recovered in Corbridge over the years could not be assigned to any of these divine shrines.

Temple I.

The platform of this building consisted of heaped earth, which was surrounded by retaining walls made of hewn stones with a width of 7.40 and a length of 10 meters. On the north facade stood five - irregularly spaced - columns. Their bases were 0.3 meters square, they were probably between 3 and 3.60 meters high. At least the northeast corner of the temple may have been destroyed during the barbarian invasion of 296.

Temple II

The temple stood on the east side of Temple I. Its platform was 9.4 meters wide and at least 16.9 meters long. There were four pillars at the front, two on either side of the entrance to the cella, the sanctuary of the temple. The courtyard was surrounded by a covered colonnade. At the back of the courtyard, there was a massive stone platform on which an altar was probably placed.

Temple III

It stood east of Temple II. Only the front of its 27 meter wide platform can be seen.

Temple IV

It stood northeast of Temple III, behind Temple V, in contrast to the temples mentioned above, which faced west or east. Its platform was 8.7 meters wide and 9.7 meters long.

Temple V

The building was oriented from east to west. Its platform was 8 meters wide and at least 13 meters long. It was built over the remains of Temples III and IV.

Temple VI

This temple was in the western enclave of the temple district. Its platform measured 3.6 × 7.3 meters. It is the smallest of the cult buildings known so far in Corbridge. It ran from north to south, its front probably facing north, towards the main street of the civil town.

Temple VII

It was immediately south of Temple VI. Only the southeast corner of its platform is known. The building was probably oriented from east to west.

Tyne Bridge

In Roman times there was a bridge in Corbridge, on which Dere Street crossed the Tyne. At low tide you can still see their pillar foundations today. The bridge, resting on a total of seven arches, was about 10 meters high and was made entirely of stone. The roadway was probably lined by a balustrade on which statues were placed on 0.8 meter wide, octagonal bases. The access ramp was eroded over time and fell into the river sometime during the early Middle Ages. This made the bridge unusable - at least for wagons. It eventually became completely useless and eroded by the relocation of the river bed. The stone material was 670 u. a. used to build St. Wilfried's Church in Hexham. 300 blocks of their southern access ramp were recovered from the river bed in the winter of 2004-2005 and stacked further upstream, 350 meters from today's Tynebrücke.

economy

Corbridge's prosperity was likely due in large part to services and trade with the crews of Hadrian's Wall. It probably only became an important market and trading center for the indigenous British of the surrounding area after 200 AD. Villa rustica and other signs of the cultivation of the land by a Romanized elite are still missing in their hinterland.

Cult and religion

The cults practiced locally included that of the Romano-British god Apollo Maponus and that of Jupiter Dolichenus, who came from Syria. Whether Christianity had already gained a foothold here is still disputed. Over 20 altar stones were uncovered in Corbridge, which are dedicated to the classical deities from the pantheon of the Greeks and Romans.

Most of the altars are those of Apollo Maponus (four of them), followed by three dedications to the Germanic god Veterus , a Germanic deity who was worshiped in Britain under a variety of other names (Veter, Veteres, Viter and Votris). The other gods, of which more than one altar is known, are Jupiter Dolichenus and the Discipla, each with two dedications. One copy each were deities such as Astarte , who originally came from the Semitic region, Concordia , Diana , Hercules (written in Greek), Mercurius (relief), Minerva , Panthea , Silvanus , Sol Invictus ( Mithras ) and dedicated to Victoria ; Six more inscription stones were made for gods whose names are illegible or unknown.

Burial ground

The finds of several gravestones prove that there must have been a burial ground in Corbridge. One had been donated by Julius Primus for his deceased wife. On the gravestones of the soldiers [...] councils of Palmyra and Flavius, their years of life were indicated, 68 and 27 years. Another example was set by Nobilis for her daughter Ahteha. Ahteha could refer to a Germanic name, e.g. B. Ahtard or Āctohildis. Children were also buried in the grave field: Sudrenus commissioned a stone for Ertola / Vellibia. She lived only four years and 60 days, another stood on the grave of Julia Materna who died at the age of six. The stone was set by her father, Julius Marcellinus.

literature

- John Leland: Itinerary . Ed .: T. Hearne, 1711.

- William Camden: Britain, or, a Chorographicall Description of the Most Flourishing Kingdomes, England, Scotland, and Ireland. London , 1610.

- John Horsley, Britannia Romana , London, 1732.

- Alexander Gordon: Itinerarium Septentrionale , London, 1726.

- John K. St. Joseph: Air Reconnaissance of North Britain. Journal of Roman Studies XLI, 1951.

- Robin G. Collingwood, RP Wright: The Roman Inscriptions of Britain , Part I Inscriptions on Stone , Oxford 1965.

- MJT Lewis: Temples in Roman Britain , Cambridge 1966.

- RW Davies: The Roman Military Diet . Britannia II, 1971.

- Malcolm Todd: The Small Towns of Roman Britain. Britannia 1, 1970, pp. 114-130.

- EJ Bickerman: Chronology of the Ancient World . Thames & Hudson, London, 1980.

- Ronald Embleton, Frank Graham: Hadrian's Wall in the Days of the Romans . Newcastle, 1984.

- Michael Bishop, John Dore: Corbridge: excavations of the Roman fort and town, 1947–1980 , HBMCE, 1989. PDF file

- MC Bishop, JCN Coulston: Roman Military Equipment from the Punic Wars to the Fall of Rome . BT Batsford Ltd., London, 1993.

- MC Bishop: Lorica Segmentata , Volume 1, JRMES Mon. 1, 2002.

- Lindsay A. Jones, MC Bishop: Excavations at roman Corbridge. The Hoard . English Heritage, 1988, ISBN 978-1-85074-191-6 .

- Hadrian's Wall Map and Guide by the Ordnance Survey, Southampton, 1989.

- Chris Scarre: Chronicle of the Roman Emperors . Thames & Hudson, London, 1995.

- Les Turnbull: Hadrian's Wall History Trails Guidebook IV. Newcastle, 1974.

- Eric Birley: Corbridge Roman station (Corstopitum) , Northumberland [guide], 1954.

- Eric Birley: Arch. Ael . 37, 1959.

- Peter Salway: The Frontier People of Roman Britain , 1965.

- D. Bourne: Arch. Ael. 45 , 1967.

- B. Birley: Guide to Corstopitum , 1954.

- Bowman, Thomas: The Vindolanda Writing-Tablets II (Tabulae Vindolandenses II) , 1994.

- IA Richmond: Roman and native in North Britain , 1958.

- Paul Bidwell: The Roman bridge at Corbridge. Hadrian's Wall 1999–2009: A Summary of Recent Excavation and Research , Editor Nick Hodgson, Verlag Kendal, 2009.

- WH Knowles, RH Forster: Corstopitum: report on the excavations in 1908, Archaeologia Aeliana , No. 3 and No. 5, 1909, the same: Corstopitum: report on the excavations in 1910, Archaeologia Aeliana , No. 3 and No. 7, 1911,

- Nick Hodgson: The development of the Roman site at Corbridge from the first to third centuries AD ', Archaeologia Aeliana , No. 5, 37, 2008.

- David Breeze, Brian Dobson: Hadrian's Wall . 3rd edition, London, 2000.

- J. Hind: The Romano-British name for Corbridge. Britannia: a journal of Romano-British and kindred studies , No. 11, 1980.

- Eilert Ekwall: Oxford Dictionary of English Place-names. Clarendon Press. Oxford. 1936-1980.

- Albert Rivet, Colin Smith: Place-names of Roman Britain. Batsford Ltd. London. 1979-1982.

- AD Mills: Dictionary of English Place-Names. Oxford, 1998.

- Bethany Fox: The Celtic Place-Names of North-East England and South-East Scotland. The Heroic Age, 10, 2007.

- John Gillam: The Roman forts at Corbridge. Archaeologia Aeliana: or miscellaneous tracts relating to antiquity , Series 3, Full. 1 (1904) - 21 (1924), 1977.

- Thomas Fischer: The army of the Caesars. Archeology and history . With contributions by Ronald Bockius, Dietrich Boschung and Thomas Schmidts. Pustet, Regensburg 2012, ISBN 978-3-7917-2413-3 ; 2nd, revised and updated edition 2014, ISBN 978-3-7917-2413-3 .

- Peter Connolly: The Roman Army, Tessloff Verlag, Hamburg 1975, ISBN 3-7886-0180-9 .

- Henry Russel Robinson: The Armor of Imperial Rome . Arms & Armor Press, London, 1975.

- Guy de la Bédoyère : Hadrian's Wall: history and guide. Tempus, 1998, ISBN 0-7524-1407-0 .

- Nick Hodgson: Roman Corbridge: Fort, Town and Museum. English Heritage Guidebooks, 2015.

- Tony Willmott: Hadrian's Wall: Archaeological research by English Heritage 1976-2000.

- Stephen Leach, Alan Michael Whitworth: Saving the Wall: The Conservation of Hadrian's Wall 1746-1987. Amberley Publishing Limited, The Hill, Stroud Glouchestershire 2011. ISBN 978-1-4456-0018-5 .

Web links

- Archaeological Park and Museum on FLICKR

- City location on Vici.org.

- Coriosopitum on English Heritage

- Roman Inscriptions of Britain (English)

- Coriosopitum on ROMAN BRITAIN

- Corbridge Castle on Pastcape

- Corbridge on Historic England

- Corbridge on Per Lineam Valli (English)

- Reconstruction and illustrations v. Original finds of a Lorica Segmentata Corbridge Type A (Robinson 1975)

- Illustrations of components of Corbridge type A and B (English)

- Corbridge hoard at Roman Britain

- Theories on the origin of the place name

Remarks

- ↑ Hind 1980, 165-171.

- ↑ It. Ant. 464, 3, Tablets II (Tabulae Vindolandenses II) (1994) 154.7, Ravenna 142 (Rav. 30), Richmond 1958, p. 140, Bowman / Thomas 1994, p. 154., Mills 1998 , RC 142, Rivet / Smith 1979, pp. 322-323, Breeze 2006, Bethanie Fox 2007, Corebrig around 1050; Et Corabrige around 1130; Colebruge at 1100-1107; Corebrigge around 1158.

- ↑ RIB 2296 , RIB 2297

- ↑ Alexander Gordon 1726, p. 176, Grew 1981, p. 322, Willmott 2000, p. 50, Leach / Whitworth 2011

- ↑ Birley 1954, pp. 1-31.

- ↑ Thomas Fischer 2012, p. 168, Bishop / Coulston 1989, p. 32, 1993, p. 191 and 2002, p. 23, HR Robinson 1975, p. 177, Peter Conolly 1975, p. 48.

- ↑ RIB 1142 , RIB 1151 , Bedoyere 1998, p. 133.

- ↑ Bedoyere 1998, p. 131

- ↑ Turnbull 1974, pp. 3-23, Embleton / Graham 1984, pp. 98-113.

- ↑ English Heritage: Members and Visitors handbook 2008/2009, p. 242

- ^ RIB 1171

- ↑ RIB 1127 , RIB 1136 , RIB 1147 , RIB 1148 , RIB 1177

- ↑ RIB 1120 , RIB 1122 , RIB 1125 , RIB 1131 , RIB 1132 , RIB 1134 , RIB 1137 , RIB 1149 , RIB 1159 , RIB 1160 , RIB 1161 , RIB 1162 , RIB 1163 , RIB 1175 .

- ↑ RIB 1130 , RIB 1149 ,

- ↑ RIB 1172 , RIB 1178

- ↑ RIB 1128

- ^ RIB 1186

- ↑ RIB 1147 , RIB 1151 , Bedoyere 1998, pp. 132-133.

- ^ Archaeologia Aeliana 1909, pp. 302-424, Forster / Knowles AA 1911, pp. 143-267, Breeze / Dobson 2000, p. 134, Hodgson AA 2008, pp. 47-92 and pp. 63-65.

- ↑ Bedoyere 1998, p. 132

- ↑ RIB 1120 , RIB 1122 , RIB 1124 , RIB 1129 , RIB 1131 , RIB 1138 , RIB 1139 , RIB 1140 , RIB 1141 , RIB 1169 , RIB 1172

- ↑ RIB 1174 , RIB 1180 , RIB 1181