Bremenium Fort

| Castle High Rochester | |

|---|---|

| Alternative name |

a) Bremenium b) Bremenion c) Bremenio d) Bremaenio |

| limes | Britain |

| section | Line 2 (outpost) |

| Dating (occupancy) | Flavian / Antonine , 1st to 4th century AD? |

| Type |

a) cavalry fort, b) cohort fort, c) street fort |

| unit |

a) Legio XX (Bauvexillation), b) Cohors I Dalmatorum (Dacorum?) , c) Cohors I Fida Vardullorum , d) Numerus Exploratorum Bremeniensium |

| size | Area: 2 ha (stone fort) |

| Construction |

a) wood and earth fort, b) stone fort |

| State of preservation | square floor plan with rounded corners, above ground still partly. visible |

| place | High Rochester |

| Geographical location | 55 ° 16 '51.6 " N , 2 ° 16' 4.8" W |

| Previous | Habitancum Fort (southeast) |

| Upstream | Onnum Castle |

Bremenium was a Roman auxiliary forces fort on the territory of the municipality ( Parish ) Rochester (Rochester High), County of Northumberland , England .

Founded in the 1st century AD, the warehouse was completely renewed in the 2nd century and repaired several times in the 3rd and 4th centuries. His crew was supposed to monitor Dere Street , an important long-distance route that led far into the inhospitable north of the British Isles. The region around Bremenium apparently also served as a staging area for military operations by the Romans (see marching camp). It continued to be occupied when the imperial frontier was taken back from the Antonine Wall to Hadrian's Wall . After that, the fort was one of the fortifications to secure the ramparts and for more than 200 years one of the northernmost military bases of the Roman Empire. Today it is one of the best preserved archaeological sites in Northumberland National Park.

Surname

The fort is mentioned in several ancient written sources: in the cosmography of the geographer of Ravenna (Bremenium) , in the Itinerarium Antonini (Bremenio / Bremaenio) on two inscriptions of the reconnaissance unit stationed in Rochester (Bremeniensum) and in the Geographia of Ptolemy (Bremenion) . In the Itinerarium , Bremenio is placed at the beginning of Iter I, twenty Roman miles from Coriosopitum . In the Geographia it appears between two other Votadini settlements ; Coriosopitum (Corbridge) and Alauna (Learchild). The Ravenna cosmography finally lists Bremenium between Habitancum (Risingham) and the so far unidentified Coccimeda . Since there is no entry in the Notitia Dignitatum , the fort was most likely no longer manned by regular soldiers in the late 4th century. The ancient place name could mean "the place / place by the rushing brook" (in Celtic brem = gushing / roaring), probably the Sills Burn flowing past the fort in the west.

location

The fort is located in Rochester, 13 miles north of Corbridge (Corstopitvm / Coria) and 5 miles northwest of Otterburn, on Dere Street (now A68), which stretched from York ( Eburacum ) to Melrose ( Trimontium ) and the Antonine Wall . It is between the motor road and the Roman road to the east. From there the Roman road ran over slightly higher terrain. Bremenium was the last Roman fortress before the Cheviot Hills and the junction with the Roman road to Learmouth. On the site of the former Roman fort, the hamlet of High Rochester developed over the centuries. Via Dere Street the fort was connected to the camps of Risingham ( Habitancum ) , 14 km away, Halton Chesters ( Onnum ) , the rampart passage at Portgate and the Corbridge supply center. The camp was in a prominent position, a spur of a ridge that slopes steeply to the north and west and afforded a good view of the south, west and north, of the Rede river valley and a little beyond. The Sill Burn flows around the fort in the northwest. The fort platform is now one of the pasture grounds of a farm, but has largely been spared from modern overbuilding. Some farm buildings are concentrated around the ramparts on the north and west sides.

Research history and range of finds

The interior of the camp was partially excavated in 1832. The fort walls were exposed between 1852 and 1855. In the course of this, the basic structures of a Roman fortress in Great Britain were revealed for the first time. However, these excavations were poorly documented. Another smaller excavation took place in 1935. The Principia, a section of the inner Wallstrasse ( via sagularis ) and a 5.7 meter long, L-shaped barracks block were observed. Since then, no major archaeological investigations have taken place in the fort.

Up to forty Roman inscriptions are known from Rochester and the surrounding area. Perhaps the most interesting find is a 67 cm high, Romano-British relief from the 2nd century AD, depicting two water nymphs on the left and right and the bathing Venus in the center. It is based on an image of Aphrodite by the Greek Diodalsas, created in the fourth century BC. The nymphs hold a water jug and a cloth in their hands while Venus washes their hair. It dates from the second or third century. The only significant ceramic find from Rochester comes from southern Gaul and could be dated to the 1980s of the 1st century AD. Otherwise mainly animal bones were recovered during the excavations (ox, sheep, pig, deer, wild boar, hare, fox and badger).

development

In 122 the Emperor Hadrian ordered a barrier wall to be built in northern Britain, reinforced by watchtowers and forts, from the Tyne to the Solway Firth, to protect the British provinces from the constant incursions of the Picts from the north. Most of the wall was built by soldiers from the three legions stationed in Britain and the Classis Britannica . Five forts (two of which were to additionally secure the tribal territory of the allied brigands ) were located as outposts north of Hadrian's Wall.

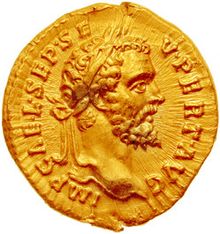

During the reign of the Flavians in Rochester in the 1st century AD (around the year 80), in the course of the campaigns of Gnaeus Iulius Agricola on the settlement area of the Votadini , a wood-earth fortification was initially built, which was expanded a little under Trajan . Recent research suggests that it was built over an early Iron Age settlement. A passage in the Geographica of Claudius Ptolemaeus (early 2nd century) reports that the "Otalini / Otadini" are also said to have lived in Alauna (Maryport) and Coria (Corbridge). Its crew was to watch over Dere Street, the main Roman supply route to Scotland, and to keep an eye on the indigenous population. The section of Dere Street near Rochester was probably a strategically important starting point for the army command for campaigns to the north, as evidence from a number of Roman marchers in the vicinity of the fortress suggests. Obviously, once Rome had consolidated its position in southern Scotland, a military presence in Rochester was seen as advantageous. Despite the victory over the indigenous tribes in the battle of Mons Graupius (83) and the building of a legionary camp in Inchtuthil on the River Tay, the Romans soon withdrew from Scotland and finally consolidated the Limes on the Tyne-Solway-Firth line. At the time Hadrian's Wall was built, the fort was temporarily unoccupied. Under the governor Quintus Lollius Urbicus , during the construction of the Antonine Wall between 139 and 142, it was again occupied with troops and converted into a stone fort that was supposed to secure the most important supply route to the north. The fort remained occupied even after the army finally withdrew from the Antonine Wall in the early 160s. Around 197 the fort was either completely destroyed or badly damaged. At the beginning of the 3rd century it was renovated during the restoration of Hadrian's Wall under Septimius Severus and - due to its exposed location - considerably reinforced. It was now also used to secure the ramparts, as the Romans probably continued to pursue their economic and military interests north of the wall. According to the inscriptions, major construction work on the fort was carried out under his successors Caracalla , Elagabalus and Severus Alexander . Until the middle of this century, Bremenium and Habitancum were occupied with reconnaissance (exploratores) , which suggests increasingly troubled times. At the end of the 3rd century the fort was destroyed again, but then rebuilt. Under Constantine the Great , a large part of the Roman troops north of Hadrian's Wall was withdrawn from 312 onwards. Perhaps as a condition of a peace treaty with the Caledons and Maeters. Around the middle of the 4th century (343 or 360) Bremenium was again burned down by the Picts and then finally abandoned by the Romans. Bremenium is no longer mentioned in the Notitia Dignitatum , written in the late fourth century . Over the centuries, stone robberies took it down to its foundations. Within the Roman walls, two fortified farmhouses ( Bastle , one of which was at Gallow Knowe) were built in the 16th century (around 1581 ) to protect against attacks by the Border Reivers . The fort is now part of the Brigantium Archaeological Reconstruction Center (Department of Archeology, University of Newcastle).

Fort

Although a large part of the masonry has been destroyed today, substantial remains of the Roman fortress can still be seen. Parts of the western wall and the western gate (completely up to the approach of the arch) have been preserved from the fort. In particular, the lower segments of its surrounding wall (earth walls with masonry) are still almost completely visible. The western wall is best preserved. Longer sections of the Roman wall are visible above ground on the west and north sides. There, the substructures of the gates have withstood the times. Overall, the camp may have gone through four construction periods during its existence. Presumably, an extension (annex) was added on the west side of the fortress - as with the Halton Chesters ( Onnum ) fort , possibly in connection with an external bathhouse. Due to its exposed location, no large civilian settlement ( vicus ) should have developed around the fort .

Wood and earth fort

Period I: The original camp from the time of Agricola (78–85) consisted only of a rampart surrounded by a single ditch. It was removed again during the Flavian-Trajan period (69–117) and again replaced by a wood-earth camp, this time with a higher wall and surrounded by an extensive system of ditches.

Stone fort

Period II: At the time of the Antonines (139 to the end of the 2nd century) the wood-earth warehouse was demolished and replaced by a stone warehouse oriented towards the northwest. The fence consisted of a core of quarry stone and clay, which was faced on both sides with hewn stone blocks. An earth ramp was built on the back of the wall for support and as a battlement.

Period III: During the reign of the Severi (211–235) the Antonine camp was demolished and replaced by an even stronger fortified camp. The internal structures were built exactly over the foundation walls of the earlier buildings. The Severan camp had a long rectangular floor plan with rounded corners, measured 148 meters (from north to south) × 136 meters (from east to west) and covered an area of almost 2 hectares. Stone platforms ( ballistarium ) measuring 9.8 meters square were added to the north wall on which catapults (onager) or sling guns (balistae) could be set up. Two inscriptions tell of their “renovation from the ground up” around 220 and later during the reign of Severus Alexander (221–235) by the Vadulier cohort (see also section Garrison). Two Roman sling balls have been walled up in the village school. This means that such artillery positions have been established there for a long time, perhaps since the time the Antonine Wall was abandoned, although it is also possible that they were only established during the wars in the 170s and 180s to make Bremenium more effective to be able to defend.

Period IV: Under Constantine I (306–337) the Severan fort was destroyed in the middle of the 4th century. The walls of the Constantinian camp that followed were slightly wider than most of the other Roman fortresses of the time.

Trench system

The fortress was surrounded by a considerable number of defensive trenches as obstacles to approach. Six of them are still clearly visible from the air. A total of thirteen of them were counted in the northwest. Only four trenches were dug on the south and east sides. It is likely that there were originally a little more (six) on the west side. Six trenches of unknown time were discovered in 1935 on the north side of the fortress. Three larger trenches were observed on the east and south sides, but they were not connected to those in the north. The purpose of the numerous, seemingly randomly running trenches from north to south or from west to east on Deere Street and on Sill Burn is unclear. Maybe they should make access to the road, north gate, and watercourse more difficult.

Gates and towers

As is customary for mid-imperial forts, the wall was broken through by a gate on each side, each of which was secured with two flank towers. The west gate is one of the best preserved fortifications. But it only had one passage. Its walls (flank towers and passage) still stand up to the northern approach of the archway (height 2.7 meters). These remains of the wall probably date from the 4th century. Dere Street reached the fort at the south gate and runs from the east gate in the direction of Sill Burn. The doorsteps are still visible from the north and south gates. The last remains of the south gate were completely leveled in the 18th century. The wall was reinforced by several square, internally attached, interval towers, one of which can still be seen. It is located between the south gate and the south-west corner of the fortress. Its front is now completely destroyed, the side walls and the rear wall up to the level of a walled-up door on the 1st floor are still preserved. Several construction periods could also be verified on it. The remains of a square corner tower attached to the inside can still be seen in the southeast corner.

Interior development

During the excavations and soundings it was found that the interior of the camp was once densely built up. In the south of the fortress, a large number of building remains have been identified as Roman, including the 21-meter-long Principia . Most of these buildings belong to period III. In addition to the Principia camp headquarters in the center and the bathing building (therme) , the fort also had the other standard buildings for medieval camps: several granaries ( horrea ) , horse stables (stabula) , team barracks (centuria) and workshops (fabricae) . Some of these buildings may have a. about hypocaust heaters . There was a cellar room under the flag shrine ( sacellum ) . Its entrance was notably secured by a massive stone slab that could be opened by sliding it into a recess using iron rollers. The camp had four storehouses (horreum) , two on either side of the Principia, in which grain or the like was stored. The mid-imperial barracks were replaced in the late Roman period - as in Housesteads and Great Chesters - by smaller, detached houses. Inside the walls, in the southeast corner, was the camp bath (balineum) .

garrison

Bremenium was probably occupied by regular Roman soldiers from the 1st to the late 4th century. During its existence it housed several cohorts of auxiliary troops (auxilia) . The following units either provided the fort's crew or may have stayed there for a limited time:

| Time position | Troop name | description |

|---|---|---|

| 3rd century AD |

Legio vicesimae Valeria Victrix ("the twentieth Valerian legion, the victorious") |

Legionaries were usually not assigned to garrison service on the border, but sent special forces for the more demanding construction projects on Hadrian's Wall. The presence of members (construction crew) of this legion is confirmed by a building inscription discovered in 1776 near the east gate. It dates from the 2nd or 3rd century AD and is flanked by reliefs. On the left is Mars, the Roman god of war, armed with a spear and shield, on the right the mythological hero Hercules with a club and lion skin. At the bottom is a boar , the symbol of the Legion. |

| 2nd century AD |

Cohors prima Lingonum equitata (the first partially mounted cohort of Lingons). |

This troop is the first demonstrable occupation of the fort. She was a 500-strong cohort from the Gallic tribe of the Lingons . The Lingons settled the Bourgogne region in what is now central France. At that time part of the province of Gallia Lugdunensis. The unit consisted of cavalry and infantry, a combination that could be used well in rough terrain. However, it is only mentioned on a single inscription from the Principia of Rochester (of forty found there). Maybe she was there until 197. The cohort is also known from other locations in Britain: Longovicium (Lanchester, Durham), possibly it was also in Coriosopitum (Corbridge). |

| 2-3 Century AD |

Cohors prima Dalmatorum (Dacorum?) (The first cohort of the Dalmatians / Dacians ) |

This unit is only known from a badly damaged tombstone that was set for one of its relatives, Sextus Aurelius. However, some researchers interpret the sequence of letters DA on the inscription not as Dalmatorum but as Dacorum . According to his curriculum vitae indicated on the stone, he served as a standard bearer ( imaginifer ) for the cohort and ended his career as a soldier with the rank of centurion . Since the presence of the unit in the same period for Maryport ( Alauna ) is well documented, it is possible that the tombstone fragment must be attributed to the Cohors I Dacorum . |

| 2-3 Century AD |

Cohors primae fida Vardullorum civium Romanorum equitata milliaria Antoniniana (the first cohort of the Vadulians, the faithful, Roman citizens, partly mounted, 1000 strong, the Antoninians) |

The cohort was originally set up from members of a tribe of the Gallaeker ethnic group . Celts who settled in the mountainous northwest of the Iberian Peninsula. The Varduli were located in a narrow strip of land that stretched on the coast (between San Sebastian in the east and Motrico in the west) and was bordered on the land side by the river Ebro , which runs between Logrono and Miranda de Ebro . The cohort is detectable in Rochester from 197 onwards. Over twenty percent of the Roman inscriptions recovered there come from this unit. At the beginning of the 3rd century, during the large-scale Caledonia campaign of Septimius Severus , your soldiers were likely to have played a key role in the restoration work in the camp. Including one of the gun platforms that was built under the command of the Tribune Publius Aelius Erasinus . Auxiliary forts were rarely equipped with heavy weapons as they were usually limited to the legions' artillery units. Another tribune of this unit who was stationed in Rochester and had a temple built for Mithras there, L. Caecilius Optatus , was probably the son or later descendant of a centurion of the same name who had risen to council member of the city of Barcino (Barcelona). Since the fort was too small for a force of 1000 men, only around 500 men are likely to have been stationed there. There is evidence that vexillation of the cohort was also used in the vicinity of Rochester, at a base near Jedburgh. Two altars were discovered there, which the Varduli unit and its then commander, the Tribune Gaius Quintius Severus, call. The inscription was donated together with a vexillation of the Raeti Gaeseti . Presumably the soldiers secured a passage over the Teviot there . The latter were stationed in Habitancum in the early third century . The presence of the Varduli is known for other North British locations as well; Castlecary ( Antoninuswall ), Longovicium (Lanchester), Coriosopitum (Corbridge) on Stanegate , Mile Fort 19 on Hadrian's Wall and Cappuck on Dere Street. |

| 3rd century AD |

Numerus Exploratorum Bremeniensium (the scouts of Bremenium) |

This unit is mentioned on two inscriptions from Rochester. Presumably she shared the fort with the Vardulier cohort. It is one of the three Roman reconnaissance units known for Britain. The inscriptions also indicate the name and rank of two of its commanders, the tribunes Cassius Sabinianus and Caepio Charitinus . |

Marching camp

In the vicinity of Rochester the remains of numerous, only briefly used wood-earth stores were found.

| place | number | description |

|---|---|---|

| Blakehope | 1 | The camp was just south of the fort on Dere Street. It had a square plan with rounded corners and consisted of a massive earth wall, surrounded by a moat, with at least four gates and an extension of the fortification to the south. The outer protective wall ( titulum ) can still be seen at the west gate . The fortress measured approximately 128 × 118 meters and covered an area of 8.6 hectares. Some of the earthworks could in part only have been created in post-Roman times. |

| Chew Green | 3 | The camps were on the slopes of the Cheviot Hills.

|

| Featherwood | 2 |

|

| Birdhope | 3 |

|

| Bellshiel | 1 | This camp covered an area of 15.9 acres and stood on a broad hill west of Dere Street, above the eastern escarpment of Bellshiel Burn and near its mouth. From there one had a good view of the river valley as well as the Bellshiel-Burn and the fort near Rochester, about 1.5 km away in the SE. To the north one could see as far as the Bellshiel Law ridge, a little over 1 km away. It had a rectangular floor plan that was slightly to the NE and consisted of an earth wall with a surrounding ditch. The east side is about 15 meters longer than the west side. Gates were on the north and south sides. The only still visible gate (south side) was secured by an internal wall (clavicula) . The latter stands up to 1 meter high, its foundation consisted of a large amount of stones. There is nothing to be seen of the other gates. In the middle of the west wall, the investigation revealed a gap in the earth wall, perhaps the location of the west gate. |

| Sills Burn | 2 |

|

| Yardhope | 1 | The camp was on the road to Learchild ( Alauna ), east of Rochester, in a heather moor at about 275 meters above sea level. d. M., between two watercourses, the Longtae Burn in the north and a nameless tributary in the south. The camp has a square plan and was surrounded by a moat. It measures about 137 meters from NE to SW, 144 meters on the transverse axis and covered an area of 2.0 hectares. On the north wall, the ditch is preserved to a depth of 0.1 meters. The earth wall there reaches a height of 0.6 meters. On the west side, the moat has been almost completely destroyed. The camp had three gates, which were originally about 5 meters wide. They were each secured by an outer earth wall. At the south and east gates they were 5 meters from the trench line. At the north gate this distance was reduced to about 1 meter because it is too close to a steep slope. |

| Bagraw | 1 | The warehouse is right on Dere Street, south of Rochester. About equidistant from Blakehope and Rochester castles. It stood on a relatively flat edge of the terrain and was oriented from NW to SE. From there you have a good view of the Rede Valley. On the southeast side, the wall was washed away by the Bagraw Burn. The A696 car road cuts through the SW quarter of the fort area. Dere Street runs parallel to the SW wall of the camp, about 5 meters away. It has a rhombus-shaped plan, in the ramparts a number of gaps are visible, which are centrally located on the SE and NE sides. They were protected by external walls ( tituli ). A street leads centrally along the longitudinal axis of the camp from the SE gate to the NW wall, but no gate can be seen there. An extension (3.5 hectares) stood on the SE side of the camp. |

| Dargues | 1 | The camp was south of Rochester, also near Dere Street, northeast of Rede. It had a playing card-shaped floor plan and had four gates, which were protected by internal earth walls ( clavicula ). The gates are centrally placed on the south-west and north-east side. The NW and SE walls run 40 meters to the northeast; so the camp was oriented in this direction. The NE and SE sides were probably a bit shorter. It covered an area of approximately 5.9 hectares. The Dargues Burn flows southeast of the camp, Dere Street runs along the northeast wall. Drainage ditches created in modern times have destroyed the ramparts in many places, especially on the north-east side. The SE corner is built over by buildings from the Dargues Farm. |

Petty Knowes burial ground

More than 100 burial sites were discovered on the area of the burial ground, which are recognizable as low round mounds ( tumuli ) , some of which are still between three and four meters high. Some are also surrounded by a ditch and an earth wall. Most of the area is south of the ancient route of Dere Street (Petty Knowes corridor), some of the barrows are also on the north side of the street. Part of the burial ground was excavated in the 1970s. It was found that each of the graves contained a central pit with ash remains from a cremation ( ustrina ) . Men, women and children were buried on the cemetery, presumably residents of the nearby fort (camp service?). In addition, four monumental graves with round, long rectangular and square ground plan set in stone were found. The circular specimen was decorated with two stone sculptures, an animal head and a pine cone. They were probably the burial places of Roman officers. One of the burial mounds dates back to the Bronze Age and was examined by Henry McLauchlin in the 19th century. It measured 8 × 6 meters, had a central fire pit and was piled up from earth and stones.

See also

literature

- Henry MacLauchlan: Memoir written during a Survey of the Watling Street from the Tees to the Scotch Border in 1850 and 1851. London 1852.

- Henry MacLauchlan: The Watling Street, from the River Swale to the Scotch Border. Privately printed for the Duke of Northumberland, 1852.

- Henry MacLauchlan: Memoir: A Survey of the Roman Wall. 1852

- HD Traill, DCL and JS Mann: Social England. MA Cassell and Company, Limited, London, Paris, New York & Melbourne, 1902.

- Madeleine Hope Dodds: A history of Northumberland, the parish of Simonburn, the parish of Rothbury, the parish of Alwinton (1893-1940). Therein IA Richmond: The Romans in Redesdale. Vol. 15, 1940.

- Humphrey Welfare, Vivien Grace Swan: Roman camps in England: the field archeology, Royal Commission on Historical Monuments (England), London 1995. ISBN 0-11-300039-1 .

- Albert Rivet, Colin Smith: Place Names of Roman Britain. Batsford, London, 1979.

- Robin George Collingwood: The Archeology of Roman Britain. Methuen, London, 1930.

- RG Collingwood, RP Wright: The Roman Inscriptions of Britain. Vol. 1, Inscriptions on Stone, Oxford 1965.

- Guy de la Bédoyère: Hadrian's Wall: history and guide, Tempus, 1998, ISBN 0-7524-1407-0 .

- RJA Wilson: 2004. The Roman 'officer's tomb' revisited at High Rochester. Archaeologia Aeliana, 5th series No. 33, 2004.

- Madeline Hope-Dodds: A History of Northumberland, Volume 15, Newcastle upon Tyne 1940.

- AR Burn: The Romans in Britain - An Anthology of Inscriptions. Blackwell, Oxford, 1969.

- RW Davies: The Roman Military Diet. Britannia II, 1971, pp. 122-142.

- BR Hartley: The Roman Occupations of Scotland. Britannia III, 1972, pp. 1-55.

- EJ Bickerman: Chronology of the Ancient World. Thames & Hudson, London, 1980.

- S. Ireland: Roman Britain - A Sourcebook. Routledge, New York, 1986.

- Chris Scarre: Chronicle of the Roman Emperors. Thames & Hudson, London, 1995.

- AJ Berggren: Ptolemy's Geography. Princeton University Press 2000.

- David Breeze: The Northern Frontiers of Roman Britain, 1961.

- David Breeze: Roman Forts in Britain. Shire Archeology, Oxford 2002.

- David Breeze: The Frontiers of Imperial Rome. Pen and Sword Books Ltd., Barnsley 2011.

- DB Campbell: Roman Auxiliary Forts 27 BC-AD 378. Osprey, Oxford 2009.

- H. Davies: Roman Roads in Britain. Shire Archeology, Oxford 2008.

- Nick Fields: Rome's Northern Frontier AD 70-235. Osprey, Oxford 2005.

- R. Hobbs, R. Jackson: Roman Britain. British Museum Company Ltd., London 2010.

- John Waite: To Rule Britannia. The Claudian Invasion of Britain, AD 43. History Pub Group Inc., 2010. ISBN 0-7524-5149-9

- Ian Alexander Richmond: Excavations at High Rochester. Arch. Ael. No. 13, 1936.

- IA Richmond, G. Askew: The Roman road from High Rochester (Bremenium) to Bridge of Aln. No. 8, 1937-1938.

- The Romans in Redesdale, Northumberland County History XV, 1940.

- Eric Birley: Research on Hadrian's Wall, 1961.

- Alistair Moffat: Arthur and the Lost Kingdoms. Birlinn, Edinburgh 2012.

- John K. St Joseph: Society for Promotion of Roman Studies The Journal of Roman Studies No. 45, 1955.

- Tabula Imperii Romani: Britannia septentrionalis. Oxford University Press, London 1987. ISBN 0-19-726059-4

- Otto Cuntz: Itineraria Romana. Vol. 1: itineraria Antonini Augusti et Burdigalense . BG Teubner, Stuttgart 1929; Reprinted 1990. ISBN 3-519-04273-8

- G. Parthey, M. Pinder: Itinerarium Antonini Augusti et Hierosolymitanum. Nicolaus, Berolini 1848 ( text search )

- Tabula Imperii Romani: Britannia septentrionalis. Oxford University Press, London 1987. ISBN 0-19-726059-4

Remarks

- RIB = Roman inscriptions in Britain

- ↑ RIB 1262 , RIB 1270 , Itinerarium 463-3, Iter I, Ravenna: 107-45, Rivet / Smith, pp. 276-277, based on a study by P. Jackson, included by Rivet / Smith in Place-Names of Roman Britain, it would not be impossible that BREMENIUM was the scene of a battle between the legendary King Arthur ( Breuion var , Welsh: Brewyn ).

- ↑ Guy de la Bedoyere 1998, p. 121.

- ↑ Guy de la Bedoyere 1998, p. 122

- ↑ DJ Breeze 1961, pp. 138f.

- ↑ Guy de la Bedoyere 1998, p. 121.

- ↑ Guy de la Bedoyere 1998, p. 121

- ↑ Ian Alexander Richmond 1936, pp. 171-184, Eric Birley 1961, pp. 242-244.

- ^ RIB 1284

- ↑ RIB 1276 (139-143), RIB 1091, RIB 1092 (238-244), RIB 1186 .

- ^ RIB 1289

- ↑ RIB 1272 , RIB 1279 , RIB 1285 , RIB 1421, RIB 1280 (220), RIB 2118 , RIB 1268

- ↑ RIB 1262 , RIB 1270

- ↑ H. MacLauchlan 1852, pp. 30-31, M. Hope Dodds, IA Richmond 1940, plan at p. 71, JK St Joseph 1955, pp. 84-85, Eric Birley 1961, pp. 240-242.

- ↑ Welfare / Swan 1995, pp. 75-77.

- ↑ IA Richmond 1893–1940, pp. 117, 120–121 and 124, JK St Joseph 1933–1934, pp. 239, 243 and 252, Welfare / Swan 1995, pp. 125–127.

- ↑ IA Richmond 1893–1940, p. 124, JK St Joseph 1933–1934, p. 241, Welfare / Swan 1995, p. 127.

- ↑ Richmond / Askew 1937–1938, pp. 44–52, Welfare / Swan 1995, pp. 119–120.

- ↑ Welfare / Swan 1995, pp. 72-74.

- ↑ Welfare / Swan 1995, pp. 92-95.

- ↑ Phillips 1977, p. 101, No. 274, Hope-Dodds 1940, pp. 104-105, Bosanquet 1933-1934, pp. 246-251, MacLauchlan 1852, sheet 6, Wilson 2004, pp. 25-33.

Web links

- Roman Inscriptions of Britain (English)

- Bremenium on ROMAN BRITAIN

- High Rochester CASTLES FORTS BATTLES

- Castle High Rochester on PASTSCAPE

- High Rochester Castle on HISTORIC ENGLAND

- Location High Rochester on Vici.org.

- High Rochester Roman Fort (Bremenium)

- Keys to the Past: Roman tombs at Petty Knowes (Rochester and Byrness)

- Naming