Limes Noricus

The Limes Noricus ( Ripa Danuvi Provinciae Norici ) was a border defense zone or military district to protect the Roman province of Noricum . His chain of fortifications was part of the central part of the Danube Limes . The border line ran from today's Free State of Bavaria to the federal state of Lower Austria and was continuously manned by Roman soldiers from the 1st to the 5th century AD.

The Noric Limes connects directly to the Pannonian Limes in today's Hungary . A continuous barrier such as B. in northern England or Raetia was superfluous here, since river banks could be secured with less effort in terms of people and material. For more than 400 years, the Danube formed the northern border of the Imperium Romanum . During this time numerous fortifications were built on the Austrian border, as well as civil settlements and administrative centers. These often formed the nucleus of today's cities and towns. The layout of the buildings is still determined today by the remains of Roman buildings and streets. The province of Noricum was the starting point or stage of trade and traffic routes that led to all major regions of the Roman Empire. These had to be kept clear and controlled by the army and fleet stationed there. The majority of the occupation troops were in forts, small forts and watchtowers that had been erected at regular intervals along the river bank. The Limes also had a great influence on the economic and cultural life of the civilian population, as its hinterland was one of the most important supply areas for the border troops and these were the guarantors for the rapid Romanization of the province. In contrast to neighboring Pannonia, Noricum did not play a prominent role in imperial politics until late antiquity .

The Noric Ripa is known nationwide today mainly due to its well-preserved remains of late antique fortifications and the biography of Severin von Noricum , which throws a little light on the difficult living conditions of the Provençals at the time of the Great Migration and the decline of the Western Roman Empire .

location

The entire Austrian Limes section (Noricum and Upper Pannonia) is about 357.5 km long and runs along the Danube from the German border at Passau through Upper Austria , Lower Austria and Vienna to just east of Hainburg / Wolfsthal, which is on the Slovakian border and near the Capital Bratislava is located. The Limes Noricus lies on the territory of what is now Germany and Austria . In ancient times they belonged to the province of Noricum ( Provincia Noricum ). Two new administrative units emerged from the Greater Province in late antiquity :

- Noricum ripense (Ufernorikum) and

- Noricum mediterraneum (Binnenorikum).

The provincial territory stretched from Tyrol to Lower Austria, essentially the area between the Danube, Vienna Woods , the eastern border of Styria , Save , Eisack up to the Inn and thus included a large part of what is now Austria. Also Carnuntum is the Roman chronicler Velleius Paterculus referred to in the 1st century even as Norican city. With the conversion into a Roman administrative unit, Noricum lost some strips of territory in the far east to the Pannonia , including the settlements along the Amber Road . Only inland Noricum was later expanded in the south-east, with the previously Pannonian Poetovio belonging to the new province. The Vienna Woods marked the provincial border in the east, the Danube the northern border and the Inn the western border to the province of Raetia .

topography

The areas north of the Norican Danube posed little threat. The Germanic settlement only reached the border in the east. The section near Krems also had a certain strategic importance. The uninhabited regions of the Bavarian Forest and the Bohemian Forest were hardly exposed to any danger from invasions by enemy tribes. The establishment of the border fortifications was primarily determined by the landscape on both sides of the Danube, on the one hand by geographical features, on the other hand by the need to control the old traffic routes across the Alps and to the east of them - the Noric trade route into the Bohemian Basin and the Amber Road to the Baltic States . The Roman army was confronted with a landscape that is characterized by narrow river valleys, for example in the area around the Schlögener Schlinge in Upper Austria or in the Wachau in Lower Austria and by wide basin landscapes , such as in the Linz Basin and the Tullnerfeld .

Due to its heavily forested, swampy and branched bank, the Danube ( Danuvius ) could only be crossed in a few places without any problems. Wide plains and river valleys alternated with narrow gaps. With their treacherous whirlpools, these narrow valleys were still very dangerous waters for shipping at the time. In the plains, however, the river was a strongly meandering - in some places up to 4 km wide - body of water with numerous branches and islands. That made the Danube not a borderline, but rather a buffer zone . The ban on settling the Germanic tribes in a belt 14 km from the north bank was also irrelevant here, as hardly anyone wanted to live here. When the riparian forests were seasonally flooded, they were only passable by ship. That is why the Roman fortifications were built on elevated locations or river gravel terraces, about 180–288 meters above sea level, protected against flooding. Along the Danube floodplains , only watchtowers secured the banks of the river in particularly inaccessible places.

Over the centuries, the current has also changed its course many times. Around 300 a striking climatological upheaval caused a noticeable change in the natural landscape in the Danube valley. Until then, the climate had been warm and dry (Roman optimum). Then began a noticeably cooler and more precipitation-rich period, the so-called " pessimum of the migration period ". This lasted until around 800 AD, which can also be demonstrated stratigraphically. It is considered to be one of the reasons why tribes living far north suddenly began to migrate south. Flood events also increased and were mostly more devastating than the previous ones. This was also one of the reasons why some of the Norican forts were largely washed away over the centuries (Pöchlarn, Tulln, Zwentendorf, Burgus Zeiselmauer). Wetlands and forests expanded again, which made agriculture (arable and viticulture) much more difficult and the living space of people more and more narrowed.

geography

The border between the provinces of Noricum and Pannonia ran in the Vienna Woods ( Mons Cetius ) . The Danube enters the Vienna Basin at the Vienna Gate . The Tullnerfeld lies between the Dunkelsteiner- and Wienerwald . On both sides of the Danube, extensive gravel terraces extend from Krems to the Wiener Pforte, which then merge into fertile loess soils . At Traismauer and Tulln it was possible to cross the river by fords. The Roman soldiers also built a fort at the exit of the narrow valley of the Wachau (Mautern). Another river crossing could be controlled from here. In the Nibelungengau, the Danube flows through a hilly landscape for approx. 30 km, interrupted by small-scale river valleys near Ybbs, Pöchlarn and Melk. This made it possible to station garrisons to control trade on the Danube and to keep an eye on the northern Barbaricum . In the hilly landscape of the Mostviertel , a fort was also built near Wallsee; the location on a rock spur was ideal for controlling traffic on the river. The abundant clay deposits formed the prerequisites for brickworks in the area of St. Marienkirchen, St. Pantaleon / Erla and Wilhering, from where bricks of all kinds were shipped to the Pannonian Danube fortifications. In the impassable region of the Sauwald and in the narrow upper Danube valley, Roman troops have only been identified after the legionary camp was established in Enns. To the east of Wilhering, the Danube flows into the wide basin landscape around Linz. A ford through the Danube has existed here since pre-Roman times, which was crossed by the Norican main road, which led from Carinthia and the area around the Magdalensberg to the center of Bohemia . A late antique quadriburgus in Oberranna and a small fort in Schlögen secured the deeply cut Schlögener loop . Remnants of a port facility were found near this camp; possibly they were also used to reload supplies and valuable goods from the river onto the road that led south past the fort to Eferding. The topography in Passau is dominated by the meeting of three rivers: the from the Eastern Alps coming Inn ( Aenus ), which from the west flowing, while the entire southern Bavarian traversing Danube and the north of the Bavarian Forest confluent Ilz . From west to east, the Danube breaks through the primary rock of the Bohemian and Bavarian Forests and over time has formed a deeply cut valley . Exactly at this point the Inn meets the Danube stream from the south almost vertically. Before it flows into the Danube, the Inn cuts through a crystalline mountain foothill and is diverted from the direct confluence by a block of gneiss , the left high bank of the Danube. Therefore, the course of the Inn turns to the east and flows two kilometers parallel to the Danube, until the two finally unite in a 400 m wide estuary lake. The exact course of the western border to the Inn is uncertain, but the line from the Mittenwalder Klause over the Zillertal Alps to Kufstein is likely.

Traffic routes

The creation of an extensive road network was one of the most striking achievements of the Roman Empire. After the occupation by the army, the systematic surveying and economic development of the conquered areas began. This was also a military necessity so that the troops could be relocated quickly and safely in an emergency and deployed effectively at the hot spots. For this purpose, the roads and settlements along the southern bank of the Danube had to be built or expanded, especially regionally and locally. Your facility also initiated land and resource development that was previously impossible. Almost all streets in Noricum , but especially the so-called Limesstrasse, were planned and terraced by the army. Road construction and its renovation were particularly promoted among the Severans, as several milestones in the region attest. In Noricum , the Danube formed a natural and easily navigable west-east connection; it has been used since the Roman occupation or incorporation as a province in the 1st century AD. The river and basin landscapes between the Alps and the Danube did not pose any serious obstacles to traffic. As a link between the Rhine and Danube provinces (including the long-distance connections via the Alpine passes), the province was thus in a key position. The stream and other navigable rivers allowed the fast and safe transport of bulk and more sensitive goods. The establishment of the Limes road ( via iuxta amnem Danuvium ) along the new Limes goes hand in hand with the establishment of the first auxiliary troop camps , into which the trade routes from the south of the empire flow. It was the main connection between the bank fortresses and for the most part always led along the Danube from the Pannonian Vindobona via Cetium , Lauriacum to Boiodurum and on to Augusta Vindelicum . In Ovilavis it united with the south-north route starting from Aquileia , the "Noric main road", which led from the Adriatic over the Canal Valley , the Klagenfurt Basin , past Virunum via Neumarkter Sattel , Rottenmanner Tauern and Pyhrnpass to the Danube . Side strands branched off into the provincial hinterland (e.g. Iuvavum ) at Lauriacum . It was not fully expanded until the beginning of the 3rd century. Under Caracalla (211-217) u. a. the section from Batavis to Lauriacum was rehabilitated or further expanded when the strategic location made a rapid connection between the troops on the Rhine and Danube necessary ( viam iuxta amnem Danuvium fueri iussit ). The travelers orientated themselves on the distance information of the milestones, as they can still be seen in Wels, Mösendorf near Vöcklamarkt, Weiterschwang near Gampern, Timelkam, Gemeinlebarn and Nietzing.

administration

Under the rule of Claudius , the state of occupation was ended and the new province was placed directly under the imperator in Rome. The administration was placed in the hands of procurators . Noricum was initially administered and ruled from the governor's seat in Virunum , which was on the Zollfeld near Klagenfurt . Under Caracalla (211-217) the provincial and military administration was moved to Lauriacum and Ovilava . The financial procurator, post, customs and mining administration remained in Virunum . As the headquarters of the Legion, Lauriacum was the most important military base on the Danube border between Passau and the Vienna Woods and thus also the residence of the commander-in-chief of all troop units stationed in Noricum . The imperial reforms of Diocletian (284-305) almost doubled the number of provinces and separated the civil from the military administration. In the 3rd century this led to the division of the province along the Tauern ridge into Ufernoricum, with the urban centers Lauriacum / Ovilava and Binnennoricum with the old capital Virunum , later Teurnia . At that time Ovilava, or perhaps in the 4th century Cetium, became the new capital of the Ufernoricum province. This new administrative division was already in force in 304/305, as can be seen from the Passio Floriani . Like Pannonia , from then on Noricum belonged to the Dioecesis Illyrici occidentale with the administrative center in Sirmium .

Ripa

Initially, the Latin word limes stood for a road or patrol route leading to the enemy. The term changed and expanded over time. It ultimately referred to a border zone held by the Roman troops. This security system formed the outer border of the Roman Empire for almost 450 years and protected it from the barbarian tribes living north of the Danube. In Noricum it was not a matter of a limes fortified with a rampart, ditch, palisade or wall, because a river was present here as a border marker. It was an additional obstacle for invaders, but also served as a communication, supply and trade route. The Romans used the term ripa (bank) for such sections . In Noricum this was the ripa Danuvii provinciae Norici . This was not a rigid defense and fortress system on which - like modern fortress belts - the waves of attack from intruders were to break. It was primarily used to control daily border traffic, as well as traffic routes and supply lines, and above all to collect taxes from those passing through. The crews of the forts and watchtowers should only prevent the penetration of smaller bands of robbers ( latruncili ), if necessary, to spy out the border area and to report invasions to the other fortresses and the high command as quickly as possible by means of reporting riders or signals. Larger attacks then had to be repulsed by a counter-attack by the legions and cavalry troops, which were brought in either from the interior of the province or from other border sections. River limits were easier to defend, especially when the river was as wide as the Danube. However, natural conditions played a role that should not be underestimated: in winter it could either have low water or freeze over. The Danube also meandered much more strongly at that time, resulting in a lower flow velocity, which further promoted ice formation. The empire expanded its sphere of influence far to the north through its economic policy . The border crossings were secured by Roman soldiers, but still enabled a lively economic exchange with free Germania. A middle-imperial customs station (statio Boiodurensis des Publicum portorii Illyrici) suspected in Passau , which so far is only known from inscriptions, was probably located in the vicinity of the late antique Boiotro fort . When importing goods from the Gallic customs districts, quadragesima (XXXX) Galliarum , a duty of 2.5% of the value of the goods was levied. The collection of the customs duty to be paid at the borders was done by tenants ( publicani ). At that time Noricum belonged together with the Balkan provinces to the customs district of the vectigal Illyricum , it extended to the Black Sea. Attempts were also made to settle Roman legionaries on the other side of the Limes or, much more frequently, to recruit auxiliary soldiers. The Romanisation of the population thus extended beyond the Limes.

development

Pre-Roman period until the turn of the times

With its rich mineral resources, horse breeding, which was highly valued in ancient times, and excellent craftsmen, Noricum has had intensive contacts to both the south and the north since ancient times. Due to the trade routes from the Mediterranean via the Alps to the Elbe region, from Pannonia to Iuvavum and on to Gaul, the Upper Austrian central area was already heavily frequented in prehistoric times. Relations with Rome were therefore characterized by close cooperation even before the Roman expansion. Around 200 BC 13 Celtic tribes settling in Noricum united to form the Kingdom of Noricum ( Regnum Noricum ). Its center was the Magdalensberg in Carinthia . In 170 BC King Cincibilus concluded a friendship treaty ( hospitium publicum ) with Rome , around 50 BC. A Roman trading post ( emporium ) was set up on the Magdalensberg . The Noriker were particularly popular with Rome because of their tribal area, which is rich in natural resources. H. the Eastern Alps , with their iron, lead, zinc and gold deposits of great importance ( ferrum noricum ), the latter already achieved steel quality and was smelted until late antiquity. Military contacts with the Romans were also close. a. provided King Voccio Iulius Caesar horsemen to fight his opponents in the Roman civil war . As a result, the Norics, soon very impressed by the Roman way of life and culture, began to romanize themselves long before Noricum was assimilated. In the year 6 AD several legions under the leadership of Tiberius marched for the first time along the Amber Road into the territory of the Germanic Marcomanni and wintered near the later legion camp of Carnuntum . 15 BC On the orders of Emperor Augustus , the northern border of the Roman Empire was moved from the southern foot of the Alps to the Danube, which the Romans used in the upper reaches of the river based on its Celtic name " Danuvius " and as a connected river with its Greek name " Ister " or " Hister "was called. Rome also had to be sure that Noricum did not intervene in favor of the hill tribes during the campaign. They probably did not trust a contractual assurance of neutrality and, to be on the safe side, occupied the Celtic kingdom without further ado before or during the campaign. The emperor's two step-sons were commissioned with the necessary final conquest, which went down in history as the Alpine campaign . The campaign took place in a large-scale pincer attack from the south and west. Drusus led his army from Italy over the Alpine passes to Raetia to what is now North Tyrol, Tiberius came from Gaul and fought a naval battle with local tribes on Lake Constance ( Lacus Brigantinus ) . Strategically important places in the Danube region and traffic routes over the Alpine passes and the Amber Road running from the Baltic Sea to Aquileia in Northern Italy were occupied and secured. In Noricum, the annexation was largely peaceful. One of the few chroniclers who mention a fight against Noriker is Velleius Paterculus in his Historia Romana . In it he reports that Tiberius not only subdued the Raetians , Vindelikers , Pannonians and Scordiscers , but also the Norici by force of arms. The foothills of the Alps up to the Danube, which still belonged to the northeastern area of influence of the Regnum , seem to have not been very densely populated at that time, apart from the lowland regions around Linz ( Lentia ) and Vienna ( Vindobona ). Eastern Lower Austria or Northern Burgenland is therefore referred to in ancient sources as the area of the " deserta Boiorum " (sparsely populated area of the Celtic Boier ). The conquest of the Alpine region served primarily to secure the routes over the mountains to Gaul or as a connection to the east of the empire and possibly to secure the deployment and supply route for the coming campaigns into free Germania. The attempt with a campaign against the Suebi tribes (Marcomanni) to expand the Roman Empire beyond the Danube to the north or Germania had to be broken off in 6 AD due to a revolt of the Pannonians. As a result, the Romans refrained from occupying the northern areas of Noricum and Bohemia and began to build a border defense on the Danube.

1st century

In the course of the century, military units were stationed on the Noric Danube border and auxiliary troop camps were set up. The border between Noricum and Pannonia now ran west of Klosterneuburg. The first permanent legionary camp was built in the late Iberian-Claudian period in Carnuntum , which at that time still belonged to Noricum . The decisive factor for this location was the monitoring of the Amber Road, the main north-south running trade and traffic route east of the Alps, and the constant threat of the Germanic tribes of the Suebian Quaden and Marcomanni that in Northern Lower Austria, Weinviertel and Marchfeld were resident . In 45 Noricum was officially incorporated into the Roman Empire as a procuratorial province under the rule of Claudius (41-54). It is not certain whether the first auxiliary troop camps were built on the Danube under Claudius or Nero (54–68). Corresponding findings from Tulln speak for it. The Claudian rule was followed by more than a hundred years of peaceful development. This led to an economic boom with a simultaneous massive change in social life in town and country, which was accompanied by increasing Romanization . A system of client states in the run-up to Ripa also helped to secure peace. In the civil war of 69, the Noric auxiliaries were probably enlisted in Vespasian's army (69–79) and marched into Italy. The Noric procurator Petronius Urbicus sided with the Pannonian governor Tampius Flavianus on the side of Otho, who was only briefly in power . When Caecina Alienus was set on the march to Italy by the opposing Emperor Vitellius, who had been proclaimed by the Rhine Legions, with his 70,000-strong army, the Norican procurator set up his auxiliaries on the Inn after he had the bridges broken. Before there was any fighting, however, Caecina had marched off to Italy. The archaeological findings show that a linear defense concept gradually crystallized out under the Flavian emperors in the 2nd half of the 1st century. Perhaps because Emperor Domitian (81–96), based on his experience of his campaigns in Germania and Raetia, had a first fortified border built, the forts of which were connected by a road. Towards the end of the 1st century, all units stationed in Noricum had been pushed forward to the Danube and the chain of castles had been closed. 95 Noric units took part in the Dacian and German Wars on the lower Danube. In the last years of Domitian's reign, the Norse army was probably reinforced again.

2nd century

Emperor Trajan (98–117) and especially his successor Hadrian (117–138) toured the Danube provinces and reorganized the border fortifications. Trajan began the systematic expansion of the Danube Limes around 100. The Noric chain of fortresses was reinforced by the construction of further forts (Wallsee, Zeiselmauer) and the construction of the first stone-built camps (e.g. Tulln). Noric auxiliaries also took part in the Dacian Wars of Tarjan. Under Hadrian all camps in the interior of the provinces were abandoned and their garrisons finally concentrated along the Danube. The layout and construction of these military buildings on the Danube Limes show that Rome, with the demonstration of its army power, was primarily concerned with a clear demarcation of its territories from the territories of the barbarian tribes or that uncontrolled border crossings should be made more difficult. In addition, the Limes was also a border between two completely contrary economic and cultural areas. The emperor also arranged for four new units to be stationed in Noricum, which had been withdrawn from Britain for this purpose (presumably because of the completion of Hadrian's Wall ). The first border problems arose during the reign of Antoninus Pius (138-161), who tried to intervene in Germanic domestic politics by appointing a King of the Quads that was convenient for him. Between 144 and 150 Noric troops took part in the suppression of a Moors revolt in North Africa. The new, defensively oriented border defense was put to the test in the second half of the 2nd century by the Marcomannic Wars. Up until then, good trading contacts had been maintained with the neighboring Teutons, which was not least due to the Roman clientele policy, which in some cases massively intervened in the management level of the quadruped and marcomann tribes. In 167 events, however, precipitated each other. The Marcomanni first infiltrated Noricum and West Pannonia in smaller groups , before finally, united with the Quads, overran the western Danube provinces and even advanced as far as northern Italy. Although Noricum was never a focal point of the fighting, it did suffer some damage, as can be seen in particular from coin finds, inscriptions and archaeological finds. Today's research sees the trigger for these incursions in large population shifts that originated from peoples in Scandinavia and the Vistula region in what is now Poland. These tribes were increasingly pushing south and claiming new settlement space. Traces of fire and destruction on numerous, above all unfortified settlements in the Limes zone testify that the raids in Raetia, Noricum and Pannonia in particular were particularly successful. The Noric soldiers, together with the troops in Raetia, are likely to have mainly cleared the province of invading looters. In the last third of the century, the ripa between Passau and Linz was reinforced by a number of new watchtowers (Hirschleitenbach) and the small fort in the Schlögener Schlinge. The latter was built of stone in its first phase of construction. In the course of the 169 created praetentura Italiae et Alpium (special command to protect Italy and the imperial border), the Legio II Italica raised in Italy was relocated to southern Noricum. After 171 the Legion set up a camp near Celeia (Lotschitz) to secure the crossings of the Julian Alps . In the years around 170, Noric territory was increasingly affected and Iuvavum (Salzburg) and Flavia Solva (Leibnitz) devastated. As a result, Noricum became a staging area against the invaders alongside Pannonia . The establishment of a province of Marcomannia north of the Danube failed in the early stages. With two new legions raised in Northern Italy (the II. And III. Italica), an attempt was made to regain control of the precarious situation on the border. In addition, Marcus Aurelius (161–180) personally led several successful campaigns against the invaders from Pannonia from 172 on , with Roman troops advancing far beyond the Danube into the Barbaricum. After his death in 180, the new emperor, Commodus (180–192), took over the command of the war. This soon renounced an offensive policy and ended the fighting between 182 and 183. The destruction of the forts and settlements in the hinterland required extensive reconstruction work. Above all, the war had shown that the Noric Limes section with its sometimes quite confusing terrain could not be effectively defended without additional legionary garrisons. Therefore, the Legio II Italica established its new headquarters in Enns ( Lauriacum ). The border between Passau ( Batavis ) and Linz ( Lentia ) was also better secured with a small fort in Schlögen ( Ioviacum ) and presumably a number of new watchtowers (e.g. Hirschleitengraben I). The years after the Marcomann Wars were, however, a troubled period in which Noricum often became the scene of military conflicts.

3rd century

This century is commonly seen as the one of great crises. However, this only partially applies to the area to be treated here. In 199, the people of Noricum and Raetia sympathized with the usurper Clodius Albinus (195–197) and were unceremoniously declared enemies of the state ( rebelles, hostes publicos Noricae ) and punished by Tiberius Claudius Candidus ( dux terra marique ), who was entrusted with a special command . The troops, however, remained loyal to Septimius Severus (193-211). During the reign of Severus, who was proclaimed the new emperor by the Danube Army in Carnuntum after internal turmoil , the Romans also rebuilt the last of the border fortifications in Stein. Around 200 the wood and earth fort in Lentia was leveled and gave way to a stone building. The devastating Marcomannic Wars are also likely to have been the decisive reason for the defense of backward cities and settlements such as Wels ( Ovilava ) and the Wall at the Url ( Locus Felicis ) with massive stone walls. Septimius Severus also expressed his gratitude to the Danube Army with extremely generous donations , which once again ushered in a period of economic and cultural prosperity on the Limes. This last heyday of the province under the Severer Emperors (193-235) is particularly evident in the rapid reconstruction of the cities destroyed by the Marcomann Wars. Caracalla (211–217) continued the expansion work by promoting the repair and expansion of the road system in the Norico-Pannonian border area, as several milestones from this period prove. The civil town of Lauriacum was perhaps elevated to a municipality during this period . This also took into account their importance as a Noric military center and Danube port for the Pannonian fleet. In 213 a new, dangerous enemy of the Romans came into action on the upper Danube, the Alamanni . Starting from Raetia, they soon worried Noricum as well . The time after that was more or less peaceful until there were serious clashes with hostile tribes again under Severus Alexander (222-235) and especially Gallienus (253-268). Their raids were repeated several times during the time of the soldier emperors and lasted until the second half of the 3rd century. According to the current state of research, there is hardly any evidence of archeological damage to the fort locations in Lower Austria as a result of the war events, even if the ancient sources document looting by Germanic peoples in Raetia, Noricum and Pannonia after their breakthrough into northern Italy. In the peace treaty with the Marcomanni and Quadi, the Germanic tribes a. a. It is forbidden to settle in an 8 km wide strip along the northern bank of the Danube. The catastrophic effects of the Marcomannic Wars initiated an army reform in the course of the 3rd century - already begun under Severus - which brought some changes and improvements for the soldiers. You could now u. a. enter into a legal marriage during their service and live with their families outside of the camp village. As a result, a self-confident class of army members and veterans soon formed, who now however developed a much closer loyalty to their home provinces than to the Roman Empire . Although Noricum went through a less turbulent period under the soldier emperors, in contrast to the neighboring provinces of Germania and Raetia , incendiary layers and hoard finds e.g. B. in Enns ( Lauriacum ) conclude that there were also invasions of hostile tribes on the Noric Ripa, which, however, could not spread to a wildfire. The conditions on the Norican Danube at that time are difficult to grasp, but there are indications of an increasingly unstable situation on this border, as a result of which the population of Enns has partially withdrawn from the civil town into the castrum Lauriacense . In individual city quarters from the Middle Imperial period, graves were now dug, which was unthinkable under Roman law within an existing settlement. The economy and trade were probably also in dire straits, but certainly not yet completely to a standstill. Around 280 the Danube Limes was reinforced by order of Emperor Probus (276–282). With the beginning of the rule of Diocletian (284-305), the existing provinces were split up into smaller ones, these were combined into 12 larger administrative units (dioceses), and a strict separation of military and civil administration was introduced. According to Diocletian's new strategic doctrine , the new military provinces were each occupied by two legions and a fabrica scutaria (shield factory) was set up in Lauriacum to provide the troops with weapons . The constant threats caused the emperor to build the Claustra Alpium Iuliarum as a locking bar to protect northern Italy. The center of this defense system was the fortress Ad Pirum (Birnbaumer Forest in the northwest of today's Slovenia). The new commander in chief of the provincial army, who had his seat in the Pannonian Carnuntum , was now responsible as Dux of Upper Pannonia and Noricum for the military affairs of both provinces. The separation of the army into stationary border guards and a mobile field army, already initiated by Gallienus, now became standard. The extensive reform measures also affected the army and administrative structures of the Danube provinces. In the new border province of Noricum ripense established in the foothills of the Alps, a new legion was stationed in addition to the main legion in Enns . Their soldiers were supposed to secure the eastern Norse Limes section up to the border with Pannonia . Partial units of this legion made up the crew of Mautern ( Favianis ). However , no troops were moved to Noricum mediteraneum .

4th century

Around this time, there was archaeological evidence of an increased influx of Southeast Noriks and probably also Pannonians in the border region in Mautern. These new settlers came increasingly from the area around Celeia . The military is very prominent in the culture of this group. This circumstance is likely to be related to the stationing of the Legio I Noricorum in the reign of Diocletian. 341 visited Emperor Constantius II. (337-361) Lauriacum and 378 also Gratian (375-383) stayed in the city when he was on the way to Thrace to meet his uncle Valens (regent in the east from 364-378 AD) to come to the aid of Adrianople against the Visigoths and Alans . Valens was defeated and his successor was forced to settle a whole barbarian people as federates in Pannonia and Thrace. This should also have far-reaching consequences for Noricum. When the incursions of enemy tribes increased massively after the middle of the 4th century, Emperor Valentinian I (364–375) had to intervene personally in 375 and led a campaign against the Quadi in Pannonia. The emperor also ordered the last major renovation and reinforcement measures on the Noric Limes. The border was reinforced by a dense cordon of new burgi and small fortresses. Above all, the brick stamps of Ursicinus dux and Ursicinus magister, but also a building inscription from Ybbs, attest to the extensive building activity of this epoch throughout the Noric Limes. Under Emperor Theodosius I (379–395), due to the lack of Roman soldiers, more and more Germanic tribes were settled on the Limes as federates, who in turn were supposed to take over the border protection there. These now increasingly had to deal with their tribal brothers and, due to a lack of support from the imperial court in Ravenna, soon went their own way politically and militarily. As a result, the situation in the empire deteriorated more and more. In 395, Flavius Honorius (395-423) became emperor in the west of the empire, which sealed the final division of the Roman Empire. The province of Noricum was added to Westrom. In the same year the regained Marcomanni invaded Noricum and Pannonia again . This time was marked by the inexorable decline of the cities and camp villages on the Limes. The chronicler Ammianus Marcellinus even described the metropolis of Pannonia I , Carnuntum , as an abandoned and dirty nest. Around 400 there were also numerous settlements and cities near the border in Noricum , such as B. Cetium , abandoned by its population, who either fled or sought refuge in the forts evacuated by the army. In the interior of the country it mostly withdrew to hillside settlements that were easier to defend. The use of the roads had apparently become a great risk. A safe supply of the border fortifications was probably only possible by water. The withdrawal of wealthy soldiers caused by the endless confusion of the throne also brought the Provençals under increasing economic pressure. At the same time, the Danube also provided a means of contact with the Germans across the river, who not only became an increasingly important political and economic factor on the Limes in the course of the 4th century. The remaining, already heavily decimated border troops and their relatives now lived within the forts, the villages around the camps were completely abandoned.

5th century

Over the course of this century, Noricum was repeatedly the scene of peoples' movements and the associated fighting, which ultimately led to the complete collapse of Roman rule over the Eastern Alps. In the first quarter of the 5th century the Huns extended their sphere of influence to the border of Noricum. Archaeological investigations in Noric forts brought u. a. It is evident that shortly after 400 coins were in circulation almost everywhere, with the exception of Lauriacum . Presumably, the imperial court in Ravenna could no longer pay the border guards regularly from this point on. In the same year, vandals, Alans and marcomannes moving westwards destroyed several towns in the Danube provinces, as evidenced by incendiary layers in Lauriacum and Iuvavum . Only a year later, the Visigoths under Alaric passed through Pannonia and Noricum and invaded Italy. They demanded Noricum and Pannonia from Emperor Honorius (395–423) as settlement lands, but after 412 they moved to Gaul, where they founded their own empire. The general living conditions on the Danube border had remained bearable until the end of the 4th century; But the continuous reduction of the border units due to constantly flaring up internal Roman disputes or defensive struggles against the barbarians finally caused long-distance trade and the circulation of coins to collapse everywhere. The majority of the Provençals, including many veterans, now lived almost exclusively from agriculture; they became increasingly poor in the course of the 5th century. In the years between 430 and 431 a rebellion broke out in Noricum , which was bloodily suppressed by the Western Roman regent, the Magister militum Aëtius (435–454). The trigger was the much too high tax burden that had been imposed on the Provençals despite previous looting by the Alemanni. In the reign of Valentinian III. (425–455) the Danube provinces again became a parade area for Goths , Huns and Vandals . For this reason, from 433 onwards, more and more foreign costume components and non-Roman ceramics can be found in the provincial finds. The loss of the rich North African provinces to the Vandals under Geiserich in 439 forced Aëtius to withdraw further limits from the northern border to protect Italy due to lack of money . As this meant that the provincial and military administration no longer functioned across the board and there was no supply or pay, the Noric Limes had finally become obsolete. After a defeat against a coalition of Federation and Romans in the Battle of the Catalaunian Fields ( Gaul ) in 451, Attila first moved to northern Italy, but soon decided to return to Pannonia . He died in 453 and his empire quickly fell apart. There are some clear indications that the Danube Army did not rapidly lose substance until after the end of the Huns threat at the earliest. Noricum ripense remained (in contrast to Pannonia and Raetia ) formally still Roman, but had to endure constant attacks by Ostrogoths , Herulians and Suebi . Only the region in Northern Lower Austria - probably since 400 - as Foederati settled Rugiern had a slightly better ratio. In general, however, the conditions for the novels were extremely unsatisfactory ( res ambiguae ) there too , since the Rugians regularly demanded high tribute payments from them. Administration, army organization and discipline quickly deteriorated in the rest of the western empire, because Ravenna's coffers remained empty. Nevertheless, a few regular units still held their positions up to that time. But their number did not come close to that in the Notitia Dignitatum Occ. given units of the Noric-Pannonian Dux . Only a handful of dispersed soldiers (probably mostly Germanic foederati ) served in some Noric and Rhaetian forts, in Favianis , Comagena , Lauriacum and Batavis, which can be proven up to the middle of the 5th century. After the disappearance of the Roman frontier army, Noricum could no longer exist as a territorial unit.

The end of the Noric Limes

"After the death of the Hun King, the two Pannonian provinces and the other countries on the Danube were in a state of constant uncertainty." With this sentence begins by far the most important written source for the end of the Roman Limes in Austria. Around the middle of the 5th century (453) a cleric - presumably of noble descent - named Severin appeared in Noricum . He settled in Favianis , founded a monastery in front of its walls and a hermitage in a Burgus abandoned by the army - Ad Vineas ("on the vineyards") . Through his biography written by Eugippius ( Vita Sancti Severini , approx. 465 - approx. 533 AD), despite the often legendary exaggeration of his deeds, one is quite good about the political processes, but also about the social and economic situation at that time taught in Noricum and eastern Raetia . Severin not only took on the alleviation of the everyday problems of the local novels , but was also in charge of negotiations with the Teutons, especially with the Rugier rulers. In particular, the inhabitants of the Roman settlements in the eastern Raetia prima and the western Noricum ripense were exposed to almost constant attacks by plundering Germanic tribes ( Alemanni , Thuringians , Heruler ). Severin then organized the orderly emigration of almost the entire Romanesque population group between Quintanis (Künzig), Batavis (Passau) and Lauriacum (Enns) to the last remaining Roman enclave around Favianis . Only under the protection of the - unreliable - rugians could the Provençals live relatively undisturbed. After the official end of West Rome, 476, the Rugier Empire was smashed by the new ruler in Italy, Odoacer , in two campaigns between 487 and 488, as they had tried to expand their territory further south. This was the time for the Norican novels, which the Rugians had supported to the end. For the regional powers struggling for supremacy, the Noric Provençals were too valuable a labor and craftsman resource to simply leave them to their own devices. Therefore, Odoaker ordered their evacuation to Italy in 488 in order to resettle them in largely depopulated regions. Many of them obeyed his order and found a new home in southern Italy around Naples .

Post Roman time

However, some of the " Romani " stayed behind and continued to cling to their Christian-Roman traditions. In Carolingian documents they are mentioned under this name in the Danube countries. Since 468 the Ostrogoths settled in the south of Noricum. They were set on the march by the Eastern Roman Emperor Zenon to “liberate” Italy from the rule of Odoacer. In 473 they first besieged Teurnia , which was able to buy its way out. The withdrawal of the Ostrogoths, however, reduced intensive contact with Italy. Binnennoricum experienced a brief heyday under King Theodoric after 493. When in the course of this century the Bavarians first immigrated from the west and later the Avars and Slavs from the east into the area of the former province, the last important Roman cities in today's Austria fell victim to these battles. In the Middle Ages, numerous well-preserved remains of the Roman buildings must have been visible. This is also indicated by field names that are related to them or that are also mentioned in official documents. It was there u. a. notes that a number of Roman relief and gravestones were walled up in churches. Chroniclers who mention the remains of the Limes have kept their records since the 13th century. The first antiquarian collections, mostly concentrated on inscriptions, were brought together in the 15th century.

troops

Soldiers of the Roman army were not only used for guard duty, but also took care of most of the public construction activities (e.g. building roads and bridges, brick production). Riders and foot soldiers, veterans and members of the various units can in many cases be evidenced in writing by military diplomas, consecration inscriptions, building inscriptions and gravestones on the Noric Danube Limes. In the early days of Roman rule, there were no legions stationed in Noricum ( provincia inermis ). The governor only had auxiliary units, which in the beginning probably also included Noric cavalry (Exercitus Noricus) . This name is first found as a reverse legend on a sesterce from the time of Hadrian. Initially, the Illyrian Army Command stationed its troop contingents mainly in the provincial hinterland, especially along the highways that led to the Danube. This enabled both rebellious tribes to be controlled and the routes of incursion secured for potential invaders. A Cohors I Montanorum is assumed to be on Magdalensberg in the early 1st century. Some of these units, which later appear in all parts of the Roman Empire, point to an original formation of Roman auxiliary troops in the Alpine or Noric region - such as various cohortes montanorum or both an Ala and a Cohors I Noricorum as well as a number of Cohortes Alpinorum . These consisted of provincial residents without citizenship. For the four-emperor year 69, Tacitus handed over nine auxiliary units for Noricum, eight of them cohorts and the riders of the Ala Auriana . Since the middle of the 1st century, the troops were gradually assigned to the Limes. From the Flavian period onwards one can speak of a first line of defense, which was massively expanded up to the reign of Hadrian. Most of the most powerful border troops were concentrated in the more exposed neighboring province of Pannonia. Noric soldiers have been shown to serve in the Praetorian Guard in Rome.

In the distribution of the armed forces among the twelve Norican camps, strategic considerations played a role. The Linz Basin , Tullnerfeld and the Vienna Basin were obviously considered to be particularly endangered ; around half of all Roman bases on the Austrian Danube Limes and, with a nominal strength of around 17,000 men, also a large part of the Norwegian border troops were gathered here. In confusing, difficult terrain, infantry cohorts ( Cohors ) were preferred , the plains and the bases at the important road connections show a high concentration of cavalry troops ( Alae ) or mixed units ( Cohors equitata ). Since there are only three relevant military diplomas as a source , the composition of the provincial army is somewhat confusing. A total of ten auxiliary units for Noricum have become known from them . In 69 the exercitus consisted of an Ala and eight cohorts. From 106 onwards there were two or three Alen and six to nine cohorts with a total of 5000 men in Noricum , including certainly the Ala I Commagenorum , probably also the Ala I Augusta Thracum . During the time of Hadrian, the provincial army was reorganized and now consisted of three Alen - the Ala I Pannoniorum Tampiana millaria was moved from Britain between 131/134 AD - and five cohorts ( Cohors I Asturum, Cohors II Batavorum miliaria, Cohors V Breucorum , Cohors I Aelia Brittonum miliaria and Cohors I Flavia Brittonum miliaria ). With the practice of supplementing soldiers ( miles gregarius ) from their province, introduced under Hadrian , they were not only able to fall back on recruits who had already been prepared for military service through youth groups (collegium iuventutis) , but later also became a new home for their veterans . This created families with a long military tradition, which can often be traced on gravestones for four or five generations.

From the 3rd and 4th centuries, two legions served as strategic reserves. Legion, naval and auxiliary units were commanded by the respective governors. In the 3rd century, the provincial forces probably still consisted of a legion, three Alen and probably up to seven cohorts, possibly including a Cohors Maurorum . The Marcomann Wars from AD 166 to 180 brought drastic changes. Two more cavalry troops, the Ala Antoniana and the Ala celerum, were transferred to Noricum at short notice . Thereafter, they were more and more Abkommandierungen of vexillations reduced his best soldiers and horsemen to other theaters of war. Most of these did not return to their previous garrisons. Gallienus (259–268) finally withdrew all equestrian associations, including the Ala Commagenorum millaria sagittaria from Tulln, in order to set up a mobile crisis intervention army with them at Mediolanum (Milan). In doing so, he robbed the Limes troops of their offensive forces and degraded them to mere border guards. The horsemen were later ordered back to the Limes as equites promoti under Diocletian (284-305) , who revived the old concept of provincial armies . He also stationed newly established (albeit greatly reduced) legions there.

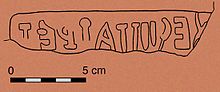

After the military and administrative reforms in the 3rd century, the border troops were divided into smaller mobile troop units in the hinterland ( Comitatenses ) and stationary units on the Limes ( Limitanei or Ripenses ). In an emergency, however, the best fighters of the Ripenses were repeatedly assigned as pseudocomitatenses to the mobile field army and the border army was further weakened. The old alen and cohort names disappear for the most part at this point in time and the greatly reduced legionary garrisons are distributed over several forts. A Dux now also commanded the previously independent units of the Upper Pannonian Army. In exceptional crises, a Comes was appointed commander-in-chief of all troops stationed on the upper and middle Danube. These military leaders - including their units and stationing locations - are recorded in the troop list of a state almanac from the end of the 3rd century AD, the Notitia Dignitatum , the Noric-Pannonian list probably reflects the status of the years between 375 and 378. They are the last written evidence for the troops stationed on the Noric Limes. The "barbarization" of the Roman army also continued to advance. The old style military disappeared. In its place came various gentile communities, bound by alliance treaties, which were supposed to defend the border for Rome. Their food, everyday consumer goods and, in some cases, their salaries had to be procured by the civil administration. Findings made in Traismauer suggest that Germanic federations settled there in the 5th century and emigrated again towards the end of the century. In Klosterneuburg numerous late antique brick stamps of the OFARN group [ OF ] ficinia [ A ] uxiliares [ R ] ipenses [ N ] orica = “Administration of the Noric Border Troops” were found. The OFARN stamps can be dated to the time of the rule of Emperors Constantius II (337–361) and Valentinian I (364–375). Since the stamp abbreviations AR , ARN and ARAN cannot be clearly explained for the time being, the previous translation suggestions remain speculative.

Noricum mediterraneum does not seem to have had any standing troops apart from the guards ( vigiles ) in the larger cities and at street posts ( beneficiaries ).

High command

As governor or procurator , who embodied the highest military, civil and judicial authority in Noricum , members of the knighthood ( equites ) were appointed procurator Augustorum provinciae Noricae in the 1st century . Their titles were changed several times later. They belonged to the ducenarii class . With the transfer of the Legio II Italica to the province, the governor also set up his seat in the camp of Lauriacum in the 3rd century . The procurators have now been replaced by the legatii from the senatorial class . These usually also took over the civil administration in those provinces in which a legion was stationed. Her official title was legatus Augustorum (also Augusti ) pro praetore provinicae Noricae . They were supported by six staff officers, the tribunes , five from the knights and one from the senators. Emperor Gallienus (259–268) removed the senators from the command level of the legions in the course of his military and administrative reforms. The new governors, who now came from the knightly rank again, officiated as agentes vices praesidis . They were originally the deputies of the senatorial legatii and carried the rank of vir perfectissimus . The command of the Noric Legion was taken over by a Praefectus ( praefectus legionis ).

In the early 4th century the provincial army was initially under the command of the governor, the Praeses provinciae Norici ripensis , but only a little later it was transferred to a newly appointed section general, the Dux provinciae Norici ripense . From the 390s a new, cross-provincial ducat was created and duces , later also comites (rank predicate vir spectabilis ), appointed commanders of the Norian and Upper Pannonian provincial forces. The Comitatenses , Ripenses and Liburnari in Noricum ripense and the Pannonia prima were now under the command of a common military leader, the Dux Pannoniae Primae et Norici Ripensis . Its title probably took into account the long independence of the Norwegian provincial forces. Most of the provinces newly created under Diocletian were too small to be able to set up and maintain sufficiently large units. They also lost importance as a military district, as the new mobile field armies operated nationwide. The militarily increasingly precarious situation in the Alpine and Danube region required the establishment of a Comes Illyrici at times in the early 5th century and thus the expansion of the high command to all of Illyria (Dalmatia, Noricum, Rhaetia and the Pannonian provinces).

The Eastern Roman historian Priskos reported around the middle of the 5th century (448/449) a. a. by an embassy of Norse dignitaries at the court of Attila , king of the Huns , who had been summoned there by the Magister militum and regent in the west, Aëtius. One of them, Primutus or Promotus, is referred to as the “head of the land of the Noriker” ( noricae regionis praefectus ), the other, Romanus, as the “leader of the host” ( militaris ordinis ductor ). If Priskos is interpreted correctly, then Promotus must have been a Praeses (inland or Ufernorikum?) And Romanus must have been the Dux of the Ufernorian border troops. Since it can be assumed that Aëtius had ordered all high Norican office holders to Attila, the office of the Ufer Norian praeses was either vacant or already obsolete at that time. Also in the lower Pannonian province of Valeria , the local Dux had taken over the civil administration in the crises of the late 4th century, which in turn could be an indication that Romanus was deployed as commander in Ufernorikum. Priskos ranks Romanus in his list after Promotus according to the traditional hierarchy, so Romanus could not have been a Comes ( vir spectabilis ). The naming of Romanus' name after that of the Noric Praeses disqualifies him as Dux according to the hierarchy of the Notitia Dignitatum , since the civil governors at the imperial court were classified as viri perfectissimi and were therefore subordinate to a Dux ( vir spectabilis ). Romanus was thus possibly the successor of Dux Pannoniae I et Norici Ripensis , whose status was reduced and who was probably already severely restricted in his area of office , who, it seems, only had the say in Ufernoricum. Aëtius had ceded the largely depopulated Upper Pannonia to the Huns in 433. This is the last written mention of high Norwegian officials.

Legions

Since there was a legionary camp in the east in addition to Vindobona in nearby Carnuntum from the 1st century, it was not found necessary for Noricum to station a legion there as well. Therefore, the province did not have its own legionary garrison until 200.

The backbone of the provincial army was the Legio secunda Italica set up by Marc Aurel around 165, around 6,000 men strong , which was first in Lotschitz near Celeia (Cluj), then after 170 in the camp of Albing and in 205 was transferred to Lauriacum under Septimius Severus . The Legion, together with the ales and cohorts of the border troops, also provided the governor's bodyguard, the singulares , stationed in Lauriacum and Ovilava . But their relatives were also active in logistics, administrative and control offices in other parts of the province. With the influx of more than 6000 Roman citizens, it also contributed significantly to the Romanization of the province. With the help of marines they secured the Ripa in the western part of the Noric Danube. According to the Notitia Dignitatum , the legion was divided into three locations in late antiquity . The headquarters should still have been in Lauriacum . Another division of soldiers was in Lentia ( Linz ) and the marine infantry in Ioviacum ( Praefectus legionis secundae Italicae militum liburnariorum, Ioviaco, possibly the small fort Schlögen ). Their trace is lost in the late 5th century.

The Alemanni incursions at the time of Aurelian (270-275) caused Emperor Diocletian to massively strengthen the troops on the Danube Limes. This was accompanied by u. a. the stationing of the newly excavated Legio prima Noricorum in Ufernoricum. This Legio, around 2000 strong, was one of the Ripenses , was probably made up mostly of Germanic tribes and was supposed to secure the eastern part of the Noric Danube Limes ( partis superioris ). Their soldiers were mainly used as milites liburnarii (marine infantry). These men were specially trained for use on Liburnians (light river patrol ships). According to the Notitia , she was stationed in Favianis and Ad Iuvense from the 4th century . According to the current state of knowledge, your stay in Mautern is considered to be reasonably secure at least until the rule of Valentinian I (364–375). The Legion probably also existed until the early 5th century AD.

Auxiliaries

The daily guard and control service at the borders took over units of lower rank, which were housed in the forts lined up along the border. Until the two legions were stationed, the provincial army consisted exclusively of cavalry units ( Alae ) and cohors of auxiliary troops ( Auxilia ). Their cohorts (strength 500 [ quinquenaria ] or 1000 men [ millaria ]) either consisted only of infantry ( cohors peditata ) or were mixed, i.e. H. Infantry and horsemen ( cohors equidata ), special forces such as B. mounted archers ( sagittari ) in Tulln and the cavalry in Traismauer secured the plain of the Tullnerfeld. From the 2nd century the so-called number units were added. The Cohors quinquenaria and Reiteralen were usually commanded by a prefect, Cohors millaria by a tribune. A decurion acted as the deputy of an equestrian prefect. From the auxiliaries the ripenses (bank guards) were formed in the 4th century . They can be proven for the first time for the year 325. However, it is not clear when this new term actually came up for the border troops stationed on the major rivers. They must have been introduced into the Roman army some time beforehand.

fleet

Another important part of the armed forces for border surveillance was the Classis Flavia Pannonica , which had been founded under the Flavian emperors (69–96) and existed with a changed organizational structure until the 5th century. The fleet was not only active for military security in the border area. Many of the tributaries flowing into the Danube, which also had to be strictly monitored, were also suitable as traffic and incidence routes. It therefore also had to keep these navigable tributaries free and should guarantee that the trade routes on the water remained safely passable. She was also responsible for transport and logistics tasks that were carried out on behalf of the military. Above all, this included the shipping of building materials and supplies. In times of crisis, the fleet soldiers, as bridge building pioneers, had to ensure a safe passage of the land troops across the Danube. It is assumed that from the middle of the 1st century the entire stretch of the Danube from Noricum, Pannonia and Moesien was controlled by their patouill ships ( Liburnians ) , but the relevant naval stations are so far little known and studied. The legions stationed in Noricum and Pannonia apparently had their own naval departments from late antiquity. Confirmation of this is once again provided by the Notitia Dignitatum . Among other things, it lists legions and their garrison locations for the late antiquity that were under the command of a Dux . Liburnarii are also given for some of these units . These marines were named after their barge-like boats ( liburnae ). From this time on, three flotillas now subordinate to the legions (each commanded by a prefect) took over this task. These were the:

- Classis (Co) Maginensis in Tulln,

- Classis Arlapensis in Pöchlarn and the

- Classis Lauriacensis in Enns / Enghagen.

The units in Pöchlarn and Tulln were essentially responsible for protecting the mouths of the Ybbs , Erlauf and Pielach as well as carrying out regular patrols on the Danube. It is possible that the unit from Tulln was later relocated to the more conveniently located Pöchlarn. The fleet members ( liburnari ) stationed in Enghagen probably mainly performed the tasks of pioneers and were also used for patrols on the Danube.

The dissolution of the provincial army

In the late period of their rule, the western Roman regents were forced to accept the constantly invading barbarian tribes as foederati in the imperial association. After the death of Theodosius (379–395), they were no longer rewarded for their services with coins, but mostly settled with land in depopulated areas on the border, which they also had to secure for Rome. The Romansh population was encouraged to take some of their defense into their own hands. In the Noric Limes forts, the Romans soon mixed with newly immigrated (Trans-Danubian) population elements. In the Vita Sancti Severini there is - with one exception - no specific references to regular occupation troops in the Noric oppida he visited in the middle of the 5th century . A Dux or Comes is no longer mentioned there either. The border army and its administrative organization should have disbanded by 476 at the latest. The chronicler of the Vita cites the following as the reason for this :

“At the time when the Roman Empire still existed, the soldiers in many cities were paid for guarding the Limes from public funds (publicis stipendiis alebantur). When this regulation ceased, the military units fell apart with the Limes. "

According to another passage in the Severinsvita, the soldiers in Batavis , in Rhaetia , who had probably been paid mainly in kind for their service , decided to march a detachment to Italy to claim the long overdue pay (extremum stipendium ). On the way there, however, she was ambushed by the enemy and cut down to the last man. In the absence of other alternatives, many of the former soldiers probably entered the service of Germanic warlords . So z. B. a man named Avitianus, who served in the retinue of the Rugier king Feva and after Severin's death plundered the monastery church in Favianis . However, the vita also shows that some of them continued to hold out in their old posts.

- Such a remnant force was in Favianis , commanded by a tribune called Mamertinus . Its "poor soldiers" ( paucissimi milites ) were evidently left to their own devices , demoralized and poorly equipped. Severin had to urgently encourage her to get weapons and supplies by attacking Germanic looters ( latrones ) on the Tiguntia ( Fladnitzbach ?).

- The crew of the obvious of them very closely guarded Comagena (Tulln) was in the second third of the 5th century, according to the Vita from Germanic federates, probably a gentile Association of Sueben or Markomannen , this assumption is also supported by ceramic finds. They treated the residents like their prisoners, but fled the city head over heels after an earthquake that Severin had begun.

- The vita also mentions vigiles (guards) and exploratores (scouts) in Lauriacum , probably a vigilante group recruited from army veterans or their descendants. Apparently the bishop Constantius, who resided there, led the defense of the former legionary camp.

Rajko Bratoz assumes that the guards in Favianis , Comagena (and in the Rhaetian Batavis ) were not military farmers or militiamen, but regular soldiers of the Western Roman army. Germanic mercenaries apparently were no longer recruited on a large scale.

Military infrastructure

Several functional phases can be distinguished in the development of the Noric Limes. In its early days, the border protection system - like the politics of Rome - still had an offensive character. The wood-earth forts were supposed to adequately secure and stabilize the newly conquered areas in order to create a safe springboard for the further expansion of the empire. As early as the 2nd century AD, however, imperial policy took on more and more defensive features. The Romans dug into the Danube and tried to secure their economically and culturally well-developed territory as well as possible. With the expansion of the border fortifications, however, a rigid, linear security system was created at the same time, which did not have any deep structure. If the attackers made a breakthrough, they could then penetrate into the interior of the provinces almost unhindered and plunder there undisturbed for a long time.

Some of the Roman fortifications in Austria were used again in the Middle Ages and have been relatively well preserved up to the present day. At no other border section of the Danube or Rhine Limes are there such completely preserved remains of towers and gates. Its remains enable the construction details in particular to analyze the reconstruction of the fortifications in the late Roman period. The Norwegian border fortifications mainly comprised cohort forts, their port facilities, as well as individual watch and signal towers, but also a customs station in Passau-Innstadt ( Boiodurum ), which controlled and channeled trade and travel. The rapid movement of troops and supplies made possible the Limes road or transport by water.

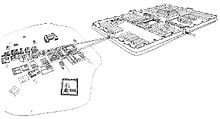

The chain of castles ran - always close to the Danube - from Passau ( Boiodurum ) in the west via Enns ( Lauriacum ) to Zeiselmauer ( Cannabiaca ) in the east. A river border could be secured relatively easily. In the case of a "wet limes", different types of military bases were located closer or closer to the shore. Between the camps, there were watchtowers at strategically favorable places or viewing points. Each fort had its own port, or at least a landing stage or storage area, as the Danube was not only a border zone but also the most important transport and trade route in the region. Beyond the border, in the Barbaricum , there were - especially in the run-up to the eastern border section - other, but only briefly used Roman fortifications such as or Marschlager (Plank am Kamp, Fels am Wagram, Poysdorf, Bernhardsthal, Niederleis, Kollnbrunn, Stillfried ad March) . While the forts in the eastern lowlands (Lower Austria) are located approximately every 15 to 20 km, the western section (Upper Austria) remained almost unpaved until after the middle of the 2nd century AD. This was also due to the fact that north of this section stretched an impassable, sparsely populated and densely forested area.

In the 3rd and especially in the 4th century AD, building activity therefore revived again due to the changed power-political and military situation on the Pannonian Limes. In late antiquity, the Noric surveillance area was organizationally divided into two parts ( partis superioris and partis inferioris ). Despite the great variety of types, the military installations of this time have some things in common. They are preferably created on hills or plateaus with steep slopes, making full use of all the advantages of the terrain. Therefore, these types of fortresses have mostly irregular ground plans that are adapted to the topography on site. Noricum is atypical in this regard. No height fortifications have been excavated on the Noric Limes; two of the three well-known late antique fortifications, Oberranna and Mauer an der Url, also have regular floor plans. Only the small fortress Boiotro in Passau-Innstadt is polygonal. The hinterland and the approach and supply routes were controlled from such small fort and road stations. The primary task of the Limes, control of border traffic and the observation and defense against invaders, did not change. Presumably, a rear line of defense was built at that time and larger settlements and cities were fortified for this purpose (e.g. Ovilava and Locus Felicis ).

Castles

The founding times of the Norican Danube Fort are very difficult to delimit archaeologically and historically. The Traismauer fort can be classified as the earliest foundation and could have existed during the Four Emperor's Year . A little later the camps in Linz and Mautern followed. By the beginning of the 2nd century at the latest - with the exception of Mauer an der Url and the Albing legionary camp - all known Norican Danube forts were built and fully manned. These include the forts of St. Pantaleon-Stein, Wallsee, Pöchlarn, Zwentendorf, Tulln and Zeiselmauer. The soldiers set them up in a "suitable place" ( loca opportuna ), i. H. At river mouths and where traffic routes from the north reached the Danube, initially in the tried and tested wood-earth construction, with a square floor plan and rounded corners, as was customary since the first half of the 1st century. Archaeological traces of palisades, ramparts, ditches and internal structures were still present in Linz, Traismauer, Mautern, Tulln and Zwentendorf. Walls made of dried mud bricks as in Tulln were extremely rare. Equestrian or Alen camps (Linz, Traismauer, Tulln) and infantry or cohort camps were set up, the former required a little more space as the horses had to be accommodated in them.

The forts of the early and middle imperial period were not intended as fortresses in which an outnumbered garrison could hold its own against the attackers for a long time. Rather, they only served as fenced barracks from which one should operate offensively against intruders. The numerous raids repeatedly led to destruction, which was usually followed by rapid reconstruction. From a 500-man infantry unit ( cohors quingenaria ) to a 1000-man cavalry troop ( ala milliaria ), the necessary fenced-in area was between approx. 1.5 and approx. 6 hectares. However, the conventional practice, from the camp size to the garrison unit to close, more and more questioned. Other units were often only temporarily - additionally - housed in such forts. The camps also had the standard four gates, each flanked by two towers. They had one or two passages, over which there was either a covered or crenellated passage. The two gates on the long sides were usually not in the center, but were slightly offset to the north side. The wooden specimens - in which only the holes in the support posts could be seen when they were uncovered - therefore only protruded slightly in front of the wall and were single or double four or six post constructions. This scheme was essentially retained in the subsequent stone buildings. At the Limes forts, there is also a tendency that the gates of the cavalry camps were provided with two passageways. After their completion, building inscriptions were often placed over the arches. The walls were additionally reinforced with square intermediate and corner towers. Of the wooden specimens, only the holes in their support beams could be seen (four for intermediate towers, six for corner towers). They are mostly reconstructed as open scaffolding with uncovered platforms that were integrated into the wall. Due to the harsher climatic conditions in Noricum , however, they were almost certainly boarded with boards or clay frameworks and covered with pent-top or gable roofs. All were replaced from the 2nd century by stone buildings of the same construction. The discovery of ashlar suggests arched windows, loopholes and tiled roofs. In the interior, the clay framework technology also predominated. Later, they too were gradually replaced by buildings with stone walls. In the Noric areas, where there were only a few stone buildings before, the appropriate infrastructure and know-how for their construction was only available after the consolidation of Roman rule. These included quarries, lime kilns and well-developed transport routes. Therefore it took a certain time until the fortifications were erected as mortar stone walls.

Although the devastating Marcomannic Wars had shown that the forts were completely inadequate in the event of major attacks, the fortress architecture hardly changed, apart from a denser network of fortifications and their rudimintary reinforcement. A whole series of Norican forts was therefore only adapted to the new fortification developments between the 3rd and 4th centuries (Traismauer, Tulln, Zwentendorf, Zeiselmauer) and were now much better equipped for longer sieges. The walls were either raised or widened for this purpose, in addition to the adaptation of the trenches, intermediate towers with a rounded front (cage arch) protruding far outwards are now being built, the corners of the camp are reinforced with fan-shaped, bastion-like towers, and gate openings are partially walled up again. In contrast to their predecessors, these structures, which were much more massive, were intended to compensate for the loss of manpower - which could no longer be replaced and therefore resulted in significantly smaller garrisons. The fan-shaped towers mostly served as platforms for heavy torsion guns . Remarkably, with the Noric horseshoe towers (Pöchlarn, Zwentendorf, Tulln, Traismauer, Mautern / Donau, Zeiselmauer), the width of the wall on the rounded, strongly pressed front ( basket arch ) was greater than on the sides and the rear wall.

The time of Valentinian I (364–375) is reasonably well documented by building inscriptions on forts and watchtowers in the Raetian, Noric and Pannonian Limes. The last extensive renovation and expansion of the Limes complex in Noricum took place under his aegis . In Mautern, the fort walls were pulled up to the banks of the Danube to ensure secure access to the river. So-called residual forts were built in the corners of the larger camps, which could be defended with just a few soldiers if necessary (Wallsee, Traismauer, Mautern, Zeiselmauer). Shortly thereafter, however, the forts completely lost their military importance and, from the 4th century onwards, changed into defended small towns due to the evacuation of the civilian population behind the camp walls. In the Vita Sancti Severini of the 5th century they are referred to as oppida .

So far, two legionary camps and thirteen cohort forts are known for Noricum :

- Legion camp Enns ( Lauriacum )

- Legion camp Albing

- Fort Passau Innstadt / Rosenau ( Boiodurum )

- Castle Schlögen ( Ioviacum )

- Fort Eferding ( Ad Mauros )

- Fort Linz ( Lentia )

- Fort St. Pantaleon-Stein

- Wallsee Castle ( Ad Iuvense )

- Fort Mauer an der Url ( Locus Felicis )

- Fort Pöchlarn ( Arelape )

- Mautern Castle ( Favianis )

- Fort Traismauer ( Augustianis )

- Zwentendorf Fort ( Asturis )

- Tulln Castle ( Comagena )

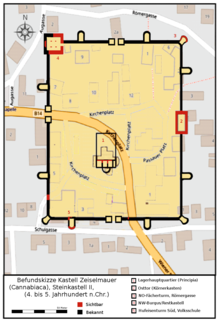

- Fort Zeiselmauer ( Cannabiaca )

Small and residual fort

An attempt was made to compensate for the shortage of soldiers that began in the 3rd century with the construction of small square fortresses (crew of around 50 men) in one of the corners of the camp. The rest of the storage area was - as with numerous other Limes forts in Europe - left to the civilian population as a settlement. Its main design features, which were introduced around the time of the Tetrarchy , persisted well into late antiquity, despite deviations from the strictly structured interior development principle that characterized the early and middle imperial periods. This includes the emerging early as the late Principate trend towards ever from the curtain walls protruding polygonal, round or even semi-circular towers, defending the fortress for archers ( Sagitarii ) and catapults ( Ballista simplified) essential.

So far, eight fortifications of this type are known on the Noric Limes:

- Zeiselmauer : The so-called "Körnerkasten" - here the east gate with its two flank towers was converted into a rectangular, tower-like structure (so-called box gate) with rounded corners.

- Zeiselmauer : Until the 1970s, the ruins of a castle / remnant fort were integrated into the building of a farm and therefore not fully recognizable. After examining the masonry, it could be identified as Roman without a doubt.

- Traismauer : When the city castle was converted into a museum and during explorations in the 1980s, it was possible to detect Roman buildings that were obviously part of a square, late antique castle or remnant fort.

- Mautern / Donau : A new building in 1982 enabled an excavation south of the Agapit Chapel. It turned out that the north wall of the bulk box rests on Roman masonry, which was rounded at the corners. The reconstruction resulted in a 30 × 21 m building which the excavators identified as the late antique remainder of Favianis fort.

- Wallsee : For the remaining crew there (probably around 50 men), a tower-like reduction or remnant fort (Burgus) was built in the south-east corner of the camp in late Roman times. The stone fort II had previously either been demolished by its residents or destroyed in an attack.

- Schlögen: The small fort was probably occupied by Roman troops from the 1st to the 5th century, served as an auxiliary camp and possibly also as a base for the Classis Histriae . The first fort was built between the last years of Hadrian's reign or during the Marcomann Wars and ends after more than a hundred years of existence around 300. In a second construction period, the late antique fort was built with the same wall circumference and - strangely enough - the same type of construction.

- Oberranna: In the late 4th century, small forts of the type quadriburgi or centenaria were added to the existing chain of fortifications on the Noric Limes . However, these only had a short lifespan and were largely abandoned in the early 5th century. The Quadriburgus of Oberranna was also destroyed by fire in late Roman times.