Comagena

| Comagena Castle | |

|---|---|

| Alternative name | a) Comagena , b) Comagenis |

| limes | Limes Noricus |

| section | Route 1 |

| Dating (occupancy) | late Flavian, around 84 (?) to the end of the 5th century |

| Type | Alen and fleet fort |

| unit | a) Ala I Commagenorum

b) Equites promoti Comagenis , |

| size | 4.2 ha |

| Construction | a) Wood and earth fort

b) stone fort |

| State of preservation | Visible during the day: U-Tower on the Donaulände ("Salt or Römerturm"), Walls of the Porta principalis dextra , |

| place | Tulln |

| Geographical location | 48 ° 19 '51.8 " N , 16 ° 3' 7.5" E |

| height | 180 m above sea level A. |

| Previous | Zwentendorf Fort (west) |

| Subsequently | Fort Zeiselmauer (east) |

Comagena is a Roman cavalry fort ( Alenkastell for 500 riders) on the Noric Limes in today's Austria . It is located in the municipality of the city of Tulln , Tulln district in Lower Austria . The area of the former Reiterkastell is spread over the area of today's Marc-Aurel -Park and the former state hospital, the northern part of the camp was completely removed by the Danube over time .

The fort's special strategic importance results from its exposed location. Its crew controlled a militarily important ford across the Danube and monitored the Tullnerfeld , which was clearly visible from here . The fort was built in the late 1st century, probably under Domitian , as a wood-earth warehouse and expanded to a stone fort at the beginning of the 2nd century. Several renovation phases are known from its occupation until the end of the 5th century. As of late antiquity was Comagena also base of the Danube fleet and location of an equestrian unit. In the west and south of the fort, excavations revealed the existence of at least two civil settlements ( vicus ) and three burial grounds . The destruction of the fort around 400 AD was followed by a phase of civilian settlement up to the end of antiquity , and resettlement began in the late 8th century.

location

Tulln is located about 40 km west of the Austrian capital Vienna on the right bank of the Danube . The entire area, the Tullner Basin and its southern part, the Tullnerfeld , was named after this Lower Austrian town . The city lies between the mouths of the Great and Small Tulln on an alluvial gravel terrace, which provided good protection against seasonal floods from the first time the Tulln basin was settled .

The Tulln Basin was largely a floodplain in antiquity , so it is only north of the Danube, at a distance of six kilometers, that the elevation of Tulln is reached again. The narrow point of the Danube on the eastern edge of the Tullner Basin made it possible to cross the river here. On the protruding tongue of solid land in an otherwise impassable Alluvialland , not only the early medieval settlement, the Tulne of the Nibelungenlied , but also the Roman fort Comagena once rose . The area of the former Reiterkastell is spread over the area of today's Marc-Aurel-Park and the former state hospital, the northern area of the camp (praetentura) was eroded over time by the Danube. Its location directly on the Danube explains the special strategic importance of the fort, on the one hand in the control of the Danube crossing, which is not only militarily important, and in the monitoring of the Tulln Field, which can be easily surveyed from this location.

Surname

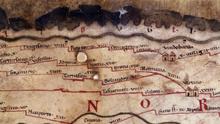

Comagena is mentioned in a number of sources in ancient literature. In the Tabula Peutingeriana Comagenis, for example, a distance of 13 Roman miles from Vindobona is given - which probably meant 23 Roman miles.

In the Itinerarium Antonini the route Vindobona - Lauriacum is described with two different routes:

- Vindobona mp XX - Comagenis mp XXX - Cetio mp XX - Arlape .

A total of four mentions can be found in the Notitia dignitatum . They are in two places

- lanciarii Comaginensis , the

- equites promoti Comagensis and a unit under the command of one

- praefectus classis Arlapensis et Maginensis

recorded.

The Roman Tulln is also mentioned in Eugippius' report in the Vita Sancti Severini : inde ad proximum quod Comagensis appelabatur oppidium declinavit .

A relief plate of Mithras from the middle of the 3rd century, which was found near Tulln, bears the following inscription:

- D (eo) I (nvicto) M (ithrae) Verus pro salute

- Comacie et Com (aciensium or magenorum) v (otum) s (olvit) l (ibens) m (erito)

Translation: "Verus honored the invincible god Mithras for the salvation of Comagenis and the inhabitants of Comagenis (or Commagene) gladly and according to merit."

In 2000, during restoration work on the eastern gate, a building inscription was discovered with the name of the cavalry troops stationed in the Tulln camp, the ala I Commagenorum . This Ala is named after its original recruiting area, the small northern Syrian kingdom of Commagene in Asia Minor. This also provides clear evidence that the military camp in Tulln is equated with Comagena.

development

The available evidence suggests that the fort was built under Emperor Domitian (81–96). The early wood-earth camp was built on cleared ground, with a high degree of probability by the Ala I Commagenorum , which was moved from Commagene in Asia Minor to the Danube border . The wood-earth warehouse had a facing wall made of air-dried clay bricks and was at least partially repaired during its approximately 30-year period of use.

The conversion of the wood and earth warehouse to a stone fort took place during the reign of Emperor Trajan (98–117). Large-scale destruction during the Marcomannic Wars is suspected, but no evidence of this could be found.

Repeated renovations to the porta principalis dextra and its two towers suggest several destruction and fire disasters in the 3rd century, two of which can be dated to just after 258 and 283 thanks to the coin treasures. It is assumed that this destruction can be traced back to the usurpations and civil wars of the restless 3rd century and not to invasions by foreign barbarian tribes.

In the years 337–371 (the period between the rule of Constantius II and Valentinian I ), when the Noric border troops ( Ripenses ) were under the command of the border general ( Dux ) Ursicinus , which is also documented in writing , one last major renovation was carried out of the camp tackled. Another severe destruction of the camp was established in the second half of the 4th century, with the east gate covered with Ursicinus stamps from the Legio II Italica burned down; the thick layer of fire indicates that this fire may have devastated the rest of the camp as well. As part of a rapidly implemented reconstruction program, the southern passage of the gate was bricked up.

The many finds (ceramics, etc.) as well as the numerous late antique graves around the camp are clear evidence of the further use of the camp in the last phase of Roman rule in Noricum. In the late 4th century, the camp was largely taken over by the civilian population and only defended by a greatly reduced garrison. According to Vita Sancti Severini , the last occupying force of the camp / oppidum consisted of Germanic federations, this report is supported by ceramic finds in the area of the southern camp tower. The Vita Sancti Severini also reports on an earthquake during Severin's stay in Comagena. Further sources materials and observations in the cemeteries confirm that the camp at the Rugierfeldzügen abandoned and probably due to the resettlement command Odoaker (probably around the year 488) from the Romanesque was abandoned population.

Even if it has not yet been clearly proven, it is assumed that the ruins of the fort were repopulated by Charlemagne in 791 during the Avar War . Archaeological evidence for this is available at least for the 10th century. In the early Middle Ages, a castle was built on the ruins of the Roman camp, which was later converted into a monastery.

Research history

Despite repeated discoveries of individual finds and graves in the previous two centuries, extensive and systematic archaeological excavations in the Tulln area have only taken place in the last few decades. This is all the more astonishing since the discovery of numerous finds led to the assumption at a very early stage that there must have been an important Roman settlement in Tulln.

Early reports

The first finds of Roman origin in the Tulln area are known as early as the 16th century. In the years around 1730 in St. Andrä or Königstetten im Tullnerfeld a Mythras relief made of white marble, which is now in the Tulln Roman Museum, was recovered.

As early as 1861, several relief stones were recovered from the demolition material of the Vienna Gate, in which these had apparently been used as building material for the medieval city fortifications of Tulln. At the end of the 1860s, in the immediate vicinity of the train station, a larger ancient burial ground, which mainly consisted of cremation burials, was uncovered. More graves were excavated in the 1880s. In the years that followed, there were repeatedly a number of other individual finds that brought stamped bricks, ceramics, coins from Vespasian to Galerius and other smaller objects to light.

To the south-east of Tulln, near the town of Nietzing, a milestone was rediscovered at the current location at the end of the 19th century , which is first mentioned in a source from the 14th century. This milestone indicates the course of the Limes Road to Cetium .

20th century excavations

Despite this noticeable accumulation of finds, a smaller, planned excavation was not carried out until 1928, led by the Viennese archaeologist Josef Nowalski de Lilia . As part of this excavation, a bronze finger ring with an attached plate showing a Christogram was recovered from the so-called Wildacker . This find was unique evidence of the presence of the first Christians in Comagena. In the same year the Heimatmuseum Tulln was founded by the “Verein Heimatmuseum Tulln” as a collection point for all archaeological finds. In the following decades, Roman graves were uncovered again, especially in the 1930s.

Especially in the years after the Second World War , there were repeated finds and small emergency excavations during construction work and new buildings in the Tulln city area, which provided evidence of extensive burial fields in the south and west outside the old town. Reports from this time repeatedly mention coin finds, especially in the area of the old town, in fields in the area around Tulln, but also from the areas north of the Danube (!). Particularly noteworthy here is the discovery of a coin hoard with over 1700 coins, which mainly contained denarii and antoninians . In 1949 there was still no precise idea of the location and the extent of the fort. Consistent observations of the finds were only carried out after 1950, especially promoted by the Tulln Local History Museum and the Austrian Archaeological Institute . In 1964, in Bonvicini Street, remnants of the wall were found, which were recognized as part of a late antique horseshoe tower of the southern fort wall. A Roman milestone was recovered in March 1968 from the demolition of a house in Kirchengasse. An archaeological investigation in 1970 at Wilhelmstrasse 10 brought further Roman finds to light. A study carried out in 1974 in the area of the Romanesque Karner led to the discovery of further Roman buildings and wooden structures with hearth pits. In 1978, when new apartments were being built south of the salt tower and east of Nibelungengasse, the western Spitzgraben area of the camp was cut. In the course of the interior renovation of the parish church, the Federal Monuments Office under the direction of Hannsjörg Ubl was able to prove Roman-era brick buildings below the church through excavation cuts. A rescue excavation by the Federal Monuments Office in 1980 in the run-up to the construction of a new hospital wing in the park of the state hospital led to further sensational finds. Within just four months, the remains of the porta principalis dextra (east gate), its two flank towers and the well-preserved walls of the older, early imperial fort, partly made of wood and adobe, were uncovered. In 1984, the so-called salt tower, a horseshoe tower on the western front of the camp, was examined and restored by Hannsjörg Ubl from the Federal Monuments Office. The southeast corner tower of the camp was excavated in 1989 by the Institute for Pre- and Protohistory of the University of Vienna.

A number of emergency excavations have been carried out since 1991 by the ASINOE (Archaeological-Social Initiative Lower Austria) on behalf of the Federal Monuments Office in the area of the former camp, in the vicus and in the southern, late antique burial ground :

- September 1991: Excavation in the area of Hauptschule Wienerstrasse - “Sporthauptschule” headed by Martin Krenn - exposure of the southern fortification.

- September 1993 / February 1994: Excavation in the Kerschbaumgasse area led by Margit Bachner - uncovering of Roman barracks.

- April 1991 / July 1992: Excavation in the Ländgasse area led by Barbara Wewerka - discovery of the western fort wall and remains of the fortification system belonging to the Roman camp.

- December 1994 / August 1995: Excavation in the Ländgasse area led by Barbara Wewerka - discovery of several construction phases of the fortification of the Roman camp.

- April to August 1991 and December 1991 to June 1992: excavation in the area of the Minorite monastery led by Johannes Tuzar, Institute for Pre- and Protohistory Vienna - evidence of a Roman civil settlement, the western vicus.

- May 1991 to the end of 1992: Excavation in the Bahnhofstrasse area - Skopik area led by Margit Bachner - salvage of the late antique grave field south with over 300 burials and settlement findings.

- 1994: Excavation in the Kirchengasse area led by Norbert Hirsch - uncovering of Roman settlement findings such as B. pits, wells and posts.

- Autumn 1995 to spring 1996: Excavation in the area of Josef-Straße / Frauentorgasse, on the "Areal Buchinger" led by Norbert Hirsch - uncovering of corpses in the area of late antique graveyard south.

- Spring to summer 1995: Excavations in the “Red Tower” area, on the area of elementary school I, led by Norbert Hirsch - uncovering of a vicus also south of the military camp.

- Autumn 1996 to spring 1997: Excavation in the Albrechtgasse / Donaugasse area, on the Volksbank site, led by Norbert Hirsch - evidence of a Roman vicus and a Roman coin depot from the 4th century.

- 1997: Excavation in the former Dominican convent, in the area of the "old hospital" headed by Norbert Hirsch - documentation of the remains of barracks buildings, inspection horizons inside the fort.

- 1998: Excavation in the Wiener Straße 24–26 area led by Norbert Hirsch - uncovering of a building complex with three verifiable construction phases.

- 1999–2000: Excavations in the area of the former state hospital led by Norbert Hirsch - discovery of the fort's principia.

In an excavation in 2000, led by G. Artner, the bottom layers of wall remains of barracks and part of the late antique ditch were uncovered at Donaulände No. 44.

During another excavation in 2000 (ASINOE, headed by G. Artner) on Langenlebarner Strasse, graves were found along the former eastern arterial road of the fort.

In the course of restoration work on the Porta principalis dextra in April 2000, two perfectly matching fragments of a cuboid were recovered, on which an inscription was carved. It was the first known written mention of the Ala I Commagenorum, a cavalry troop formerly stationed in the Tulln camp. This find made it possible to place the construction of the stone gate in the reign of Emperor Trajan.

In 2002, during an emergency excavation in the area of Nibelungenplatz 1 / Verhoniggasse 4, carried out by ASINOE under the direction of Norbert Hirsch, several phases of the development of a Roman settlement were found.

In a further excavation by the ASINOE association in 2003, headed by R. Dragan, the remains of the walls of the team buildings, a canal and a camp road were uncovered on the area at Ländgasse 5.

In the run-up to the renovation of the Tulln train station in 2005 and 2006, a large-scale excavation was carried out (BDA / ASINOE, headed by Ch. Blesl). In the bottom layer, early settlement finds, a street from the 2nd / 3rd. Century and late antique body burials can be proven.

Between 2005 and 2006, up to 250 graves from two epochs (1st - 3rd century and 4th century) were discovered in the western burial ground on plots 1 and 2 north of Schießstattgasse, on the area of the former fire brigade school.

During a rescue excavation by the Federal Monuments Office in the years 2006–2007 on the area of the old fire brigade school, led by Martin Krenn, the eastern boundary of the West burial ground and the western edge of the vicus were documented.

During an excavation in the area of Wassergasse 4 in 2007, the Federal Monuments Office documented two overlapping trenches south of the salt tower.

In the run-up to the construction of the Rosenarcade shopping center, extensive excavations were carried out again in 2006 and 2007 by the Federal Monuments Office (headed by Martin Krenn). Settlement findings, a children's grave and the boundary of the settlement could be found here.

In 2007 the main square in Tulln was archaeologically examined before an underground car park was built. Pits, ditches and post holes revealed a multi-phase Roman development.

Fort

The center of the Roman Tulln was clearly the Alenkastell. It was first built as a wood and earth construction, with a high degree of probability during the reign of Emperor Domitian (81–96). The conversion to a stone fort was carried out under Trajan. It was documented until the end of the 4th and early 5th centuries.

At least three construction phases have been proven for the stone fort:

- Stone fort with double moat;

- Stone fort with a simple moat and wall in front;

- late antique fort with a pointed moat.

Wood and earth fort

The discovery of the early wood-earth store in the park of the old Lower Austrian provincial hospital was made in 1980 as part of a rescue excavation by the Federal Monuments Office . It was under the direction of Hannsjörg Ubl and extended over an area of 30 × 50 m west of the former Dominican convent. First the east side of the fort was excavated, whereupon remnants of the wood-earth store were found. It was a wall made of large, air-dried mud bricks, up to one meter high, which could be exposed over a length of about 30 m. The post holes observed on the top of the wall are assessed as clear indications of a row of palisades originally set up here as a parapet .

Since the wall of the following stone fort was built about one meter east of the fortification of the early camp, the mud brick wall was preserved in a very good condition. It was placed on a dry stone foundation consisting of coarse rubble stones. On its western side, the wall was additionally supported by a mighty embankment that was a few meters wide at the bottom. A profile section of this embankment showed that the top of the wall could also be reached through this relatively flat ramp. The mud brick wall was slightly curved towards the west, which, according to Hannsjörg Ubl, suggests an irregular, possibly polygonal ground plan of the early camp.

In the area of this curvature, a building over the mud brick wall with lime mortar-bound masonry was found. According to Hannsjörg Ubl, these repairs are an indication that the early adobe wall had undergone some adaptations before the stone warehouse was built.

In the course of these excavations, some post pits of the gate system of the wood-earth camp were also found, which were laid out in a row. The arrangement of these post pits west of the northern and southern stone towers suggests an approximate tower width of 3.30 m. Another post pit line under the stone towers is to be expected. Analogous to the stone construction, there must have been a double gate with a spina made of wooden posts in the middle, otherwise the span would have become too large to be statically bridged with wooden beams .

A section of the upstream trench system with approach obstacles, so-called liliae , could also be observed. The investigation of the small finds in the strata of the embankment, such as B. an As Emperor Domitians, allowed a dating of the system to the penultimate decade of the 1st century.

The ASINOE association carried out some excavations north of Ländgasse (parcels 118, 128 and 129) in the area of the presumed Porta principalis sinistra of the stone fort from April 1991 to early July 1992 and from December 1994 to August 1995 on behalf of the Federal Monuments Office by Barbara Wewerka and Norbert Hirsch. Wewerka's report mentions the remains of mud bricks that fell as a fall in the moat immediately in front of the western camp wall. The detection of these mud brick remains can be interpreted as an indication of the existence of another mud brick wall on the western side of the camp. Thus the expansion of the wood-earth camp to the west would be roughly analogous to the later stone camp. During an emergency excavation from September 1993 to February 1994 in the area of Kerschbaumergasse, i.e. still inside the fort, some post moats sunk into the clay were discovered in the lowest excavation layers. Its overlay by a Roman wall suggests dating to the beginning of the 2nd century.

Stone fort

The Tulln camp has a rectangular floor plan, with its narrow side oriented towards the Danube. As with the neighboring fort of Zwentendorf , or the legionary camps of Vindobona and Carnuntum , the northern front of the camp was washed away by the Danube over time and completely removed. Proof of this is above all the salt tower, a protruding, horseshoe-shaped intermediate tower of the western camp wall, which today stands in the immediate vicinity of the Danube bank. Due to the loss of around a fifth of the warehouse area, its exact dimensions can only be estimated. The camp will originally have taken up an area of 4.2 to 4.5 hectares.

East gate

The emergency excavation in 1980 not only provided the first evidence of a wood-earth store, but also revealed the remains of the porta principalis dextra of the oldest stone store in the course of further investigations . Not only was the foundation of the eastern camp gate preserved, it was also possible to uncover and conserve remains of walls up to around two meters high.

The entire gate system is approximately 22 m wide. The lanes were about 4.20 m wide. The two rectangular flank towers, which originally reached a height of approximately four meters, measured 5.70 × 7.45 m. The interior of the towers measures 3.30 × 5.10 m. The wall thickness is 1.20–1.30 m at the front, but only 1.10 m on the other sides. The projection of the towers from the line of the camp wall is approx. 1.80 m. The tower rooms were equipped with a screed floor, and their interior walls were provided with a single-layer, rough wall plastering. The two towers each have a door opening of 1.30 m in the west. The outer walls were also plastered. Raised horizontal and vertical plaster strips, which are colored yellow, should simulate masonry made of larger blocks. The arches of the arches are colored white and red. The remains of the 1.5 m thick camp wall, which stretches north and south and had been torn down to its foundations in the Middle Ages, were also exposed. In late antiquity, the southern gateway was walled up and served from then on as a living room or storage room.

With the discovery of the eastern camp gate, the well-preserved spina wall of the double gate entrance of the porta principalis dextra , due to the location of the salt tower on the western flank of the camp and a section of the western camp wall that was discovered during construction work under Kerschbaumgasse, an accurate reconstruction was possible for the first time of the fort floor plan has been made possible. After uncovering the east gate, the course of the via principalis and cardo maximus could also be clearly localized.

Southern camp wall

In September 1991 archaeological investigations were carried out in the area of the southern perimeter wall due to the construction of a new sports hall on the premises of the Tulln Sports School. A wall about two meters thick was discovered here, running in the direction of WO, made of stones and broken bricks in a mortar bond. The remains of the wall were the foundations of the former south wall of the Roman camp. To the south of it, a bottom ditch was also found that was also deepened in the WO direction. Ceramic material from the second half of the 1st to 3rd centuries was found in the lower - undisturbed - filling. Another pointed trench ran in the same direction as the Sohlgraben and overlaid the filled older Gaben. In its backfill, heavy clay ware was discovered that could be dated to the late 1st or 2nd century. The most recent finds from the filling of the trenches date from the first half of the 5th century, so that the leveling of the Roman trenches can be assumed for the second half of the 5th century at the latest.

Barracks

During an emergency excavation in 1993/1994 in the area of Kerschbaumergasse, i.e. in the south-eastern part of the Roman military camp, the foundations of two east-facing walls with painted plaster residues were uncovered. Another wall, still around 0.90 m high, also running in an EE direction, was located in a south profile. It is likely to have been removed in late antiquity. All these remains of the wall were part of barracks. Further findings suggest that the inner camp buildings were completely destroyed as early as the 10th century.

Trench systems

Just south of the salt tower, between Nibelungengasse and the ancient camp wall, J. Köstlbauer, director of the Tulln local history museum, discovered a trench about five meters deep running in the NS direction in June 1978 while excavating a larger apartment building.

The excavations in 1991/92 and 94/95 north of Ländgasse took place at the point where the Porta principalis sinistra was suspected since the identification of the cardo maximus in 1980 . Although the excavation could not find the western camp gate, valuable information was gained for the fortification of the various construction phases of the Roman camp. The western camp wall itself and a total of four trench systems were documented:

In the course of these excavations, the solid and well-mortared western stone camp wall running from NS could be detected, which has been preserved with a width of 1.20 m and partly up to a height of 2.20 m from the edge of the foundation. A little further to the south there was only the excavation ditch dated to the Middle Ages. In the excavation area, the camp wall showed no evidence of a Roman extension such as B. a gate tower or intermediate tower. In the northern area of the excavation, a road body with a slightly arched profile was identified. It was noticeable that the two trenches of phase 2 decreased in depth in the direction of the road and were then no longer recognizable in the immediate area of the road. The earth that otherwise fills the trenches lay over the road, so that an earth bridge in front of a gate that can be assumed but has not yet been discovered can be expected.

Late antique fortress towers

From the end of the 3rd century onwards, the radical changes in the Roman army lead to the erection of military buildings with a strongly defensive character in Tulln as well. In addition to the adaptation of the trenches, intermediate towers cantilevering far outwards with a rounded front (cage arch) are now being built, the corners of the camp are reinforced with fan-shaped, bastion-like towers, gate openings are partially walled up again. In contrast to their predecessors, these buildings, which were much more massive, were supposed to compensate for the loss of manpower - which could no longer be replaced and therefore resulted in significantly smaller garrisons - through their supposedly greater deterrent potential. To further strengthen the fort, the mid-imperial corner towers were also converted into fan-shaped towers. Fan towers resemble an isosceles triangle, the legs of which protrude far outwards from the curtain intersection and are then connected by an arch. The fan-shaped towers at the SW and SE corners could be excavated and assigned to the middle of the 4th century.

Horseshoe Tower West

An outstanding example of the appearance of late Roman camp fortifications is the so-called "Roman" or "salt tower", which dates from the first half of the 4th century. Its name is based on its temporary use as a salt store in the 18th and 19th centuries. Century. It originally stood as an intermediate tower on the western fort wall, its massive masonry (height 10 m, width 1.40 m) is still Roman up to the roof edge. The inside measuring 7.20 × 12.40 m and 8 m long tower jumped 3.1 m back into the camp interior, as can be seen from the scars of the fort wall and the walled-up opening of the battlements (round arch on the north side above the today's entrance). The holes on the outer wall, which are now closed with round wood, date from the time it was built and were used to anchor the scaffolding. The original entrance can still be seen on the east side. It had four storeys - including the basement - and, like the fan-shaped towers at the corners of the fort, served to reinforce and better cover the wall in the event of attacks. The wall surface was preserved in 1984; in ancient times its facade was completely plastered.

Horseshoe tower south

As part of a canal excavation in Bonvicinigasse in 1964, not only was the southern camp wall cut, but the side wall of another U-tower was also discovered. The excavation remained unpublished, the exposed cast wall foundations of the western tower cheek of the eastern of the two intermediate towers built in the late Roman period on the southern flank of the Comagena camp (halfway between the corner towers and the Porta decumana ) were only mentioned later by Herma Stiglitz.

Fan tower SW corner

Its remains were trimmed in 1963 but only poorly documented, the scanty results published later.

Fan tower in the southeast corner

This fortification was exposed in the early 1990s. During the excavation, an approx. 60 cm thick wall was found under the corner tower from the Middle Imperial period, which could be dated to the 2nd or 3rd century. The fan tower was later built over this. Its walls were up to 1.65 m wide and up to 2.5 m high in the rising masonry. The east wall of the fort was attached to the outside, but this could only be proven in a few stone flocks. In addition, a pointed ditch was upstream. The repeated renewal of the original screed floor with white mortar screed suggests that the tower was renovated several times inside, at least until the crew left around 488 AD. Its post-ancient use from the Carolingian era to the 13th century is evidenced by a number of other inspection horizons.

port

For the port facilities of the Danube fleet stationed here according to the Notitia dignitatum, there are no archaeological evidence to date; they are assumed to be west of the fort. However, it can be assumed with a fair degree of certainty that the shifting of the course of the Danube to the south, in addition to the northern part of the fort, also completely destroyed the port.

crew

The following garrison units are known for Comagena:

| Illustration | Time position | Troop name | |

| 1st to 3rd century AD | Ala prima Commagenorum Sagittariorum ("the Commagener's first squadron of mounted archers") | The cavalry unit is named after its country of origin, the small northern Syrian kingdom of Commagene in Asia Minor . Her full name has also become known through the Stein 5 military diploma. On most diplomas, brick stamps or inscriptions it was only recognizable as Ala Commagenorum , Ala I Com (m) agenorum and the abbreviation AIC . The troops were originally part of the royal army, which was incorporated into the Roman army from 72 AD. The traces of the unit can be traced as far as Egypt, where it was probably stationed in Kalabsha , the ancient Talamis south of the first Nile cataract , and it can still be traced back to 83 AD. The mention on a military diploma from Wels / Ovilavis for the year 106 AD confirms that the troops were already standing on the Noric Limes section at that time, where they are attested by inscriptions until the 3rd century. The inscriptions found in Noricum also suggest that the troops recruited soldiers throughout the province and that members of this unit also served as singulars in the governor's guard.

However, the findings available to date leave us in the unclear whether this Ala was transferred from Egypt to the Noric Danube at the time the camp was founded, i.e. in the 1980s. Possibly it was assigned to the Danube in the course of the wars waged by Emperor Domitian in the years 88–96 with the Danube Germans. This hypothesis is supported by the fortification of the original wood-earth camp with an adobe wall, a construction technique that this auxiliary unit may have brought with it from its Egyptian station. During repair work on the eastern camp gate in the spring of 2000, two matching sandstone fragments with a carved inscription were found. It was largely supplemented by Hannsjörg Ubl and can be interpreted as follows:

Translation: “To the Emperor Caesar, son of the deified Nerva, Nerva Traianus Augustus, victor over the Teutons, victor over the Dacians, high priest, in the year of the 8th tribunician power, emperor for the 4th time, consul for the 5th time, father of Fatherland. The Ala Commagenorum Antoniniana (who built the building). " This building inscription for an unspecified building in 104 AD proves the presence of soldiers of the Ala (prima) Commagenorum in the camp. The honorary name "Antoninana" was added more than 100 years later under Emperor Caracalla (211-217) and testifies that this unit was still in Tulln at the beginning of the 3rd century. The most recent inscriptions of the Ala I Commagenorum also date from the late 3rd century, beyond that nothing is known about their further fate. |

|

| 4th century AD |

Lanciarii Comaginensis ("the spearmen in Comagena") |

In the course of the reforms under Emperor Diocletian at the beginning of the 4th century, the garrison in Comagena was expanded by setting up a unit of spear throwers. Possibly these were pulled out of field troops already lying in Tulln - perhaps as a vexillation of the Legio I Noricorum . In any case, a light and mobile operating unit was created. In the event of a crisis, their soldiers were probably drafted into the field army of Comes Illyrici as pseudocomitatenses . | |

| 4th century AD |

Equites promoti Comagenis , ("a squadron selected / assigned riders in Comagenis") |

The Notitia Dignitatum mentioned in its Norian troops list towards the end of the 4th century again an equestrian unit, probably originally was formed from Legion riders elite force. It cannot therefore have emerged from the Ala I Commagenorum . | |

| 4th century AD |

Praefectus classis Arlapensis et (Co) Maginensis ("a fleet prefect in Arelape and Comagena") |

The Notitia Dignitatum also lists a hitherto unknown base of the Late Antique Danube Fleet , the commander of which could have been based in Tulln. | |

| 5th century AD |

Foederati (mercenary) |

Around the middle of the 5th century, in the Vita Sancti Severini , a barbaric or Germanic federation troop, perhaps from Suebi - probably still under Roman command - appears as the occupation or guarding of the gates of the oppidum Comagenis when Severin arrived in 456 existing, mentioned. |

Vicus

Some parts of the civil settlements belonging to the camp could be proven in a series of excavations in the south and west of the camp. Subsequent investigations led to the discovery of the so-called "Gräberfeld Süd", a cemetery belonging to the camp and the civil town. Other burial sites, mainly to the west, but also to the east of the camp, have been partially uncovered or have become known through individual observations.

Finds that could be assigned to the southern vicus were excavated in the “Red Tower” area. Related Roman building remains were also found during the restoration work of the Karner , during the excavations within the parish church, where Roman cultural layers could be uncovered to a depth of three meters, as well as in the area of Kirchengasse, where the remains of Roman rooms with screeds and underfloor heating were discovered.

The western vicus could also be proven through a series of excavations, for example in the area of the Minorite monastery, on the excavation area Albrechtsgasse / Donaugasse, on the main square and on the area of the “Rosenarcade” shopping center. Numerous earth cellars, wells and deep pits were documented. The uncovering of the remains of a Roman row house is of particular interest .

The discovery of a coin deposit with over 100 bronze coins from around 340 AD must also be mentioned at this point. This is because other coin finds in the vicus west - Domitian (81–96) and Nerva (96–98) - suggest that this vicus already existed in the early phase of the camp.

More recent excavations in the west of the camp area have shown several construction phases of a Roman vicus. For example, a pit could be observed on plot 12 under the remaining walls of a stone construction phase, which in turn was already disrupting a foundation trench of a wooden construction phase. The coins found here date from AD 182 to 367/375.

Current finds indicate a possible further settlement area in the east of the camp area (Langelebarnstrasse).

Excavations in the floodplain of the Danube and the Kleine Tulln uncovered the remains of a villa rustica in Freundorf , which was built in the 2nd century AD. A whole series of such Roman country estates at the gates of Comagenis and near Freundorf probably ensured the food supply for the fort crew.

Burial grounds

Since the 19th century, archaeological investigations and various finds have revealed several Roman burial grounds in the vicinity of the camp area. In the area of Bahnhofs- and Frauentorgasse, the so-called grave field extends south. In the west of the camp a distinction is made between two neighboring burial grounds:

- the southwest burial ground on the grounds of Konrad von Tulln-Gasse, Wildgasse and Jahngasse as well

- the north-west burial ground, mainly on the area of the former Lower Austrian fire brigade school and to the west of it.

There is a gap of approx. 200 m between them, which makes the division into two burial fields seem justified. Even though it is still a controversial topic among experts, the cemetery in the northwest is likely to be assigned to the early days of the camp, while the cemetery in the southwest is likely to be assigned to late antiquity.

Grave field north-west: In recent years, an area of around 6000 m² has been archaeologically examined on the site of the former Lower Austrian fire brigade school, northwest of the city center. During these large-scale excavations, a burial field that was occupied from the end of the 1st century to the 5th century was uncovered, which extends from the Nussallee to the west. A total of around 164 graves (including those of five horses) were recorded, especially in the western area of the excavation area. These can be classified into two occupancy phases: an early phase from the late 1st to 3rd century in cremation burials and a phase from the late 3rd / early 4th century in which body burials were mainly observed. The area was probably originally covered with urn graves and busta, but due to their shallower level (in contrast to body burials), most of these were destroyed by medieval interventions on the site. Sporadic fire graves were also located - in this case the corpse fire and the remains of the funeral pyre are put into the grave pit - but a central cremation site (ustrina) has not yet been found.

On the grounds of the above Fire school should also have reached the eastern border of the north-west burial ground. In the eastern part of the excavation site - at a distance of about 25 m from the easternmost Roman period burial - evidence of settlement was found in the form of pits, which means that the western boundary of the western vicus can be assumed in this area.

In the Roman Empire it was forbidden to cremate or bury the deceased within cities or settlements. Accordingly, in Tulln the burial fields were created along the main arterial roads of the camp and the associated vicus. This street was excavated during excavations on the western side of the fire brigade school, in the area of Schießstattgasse 2-4, (grave field north-west). A part of the Gräberstrasse as well as 112 subsequent burials to the north were recorded. Gräberstraße is located on the current course of Schießstattgasse and corresponds to the arterial road from Porta principalis sinistra to the west. The burials are mainly cremation graves from the 1st to the beginning of the 3rd century, which differ in time from a subsequent burial phase in the 4th century.

A mid-imperial child's grave was discovered in the area of the Rosenarcade shopping center. However, this grave definitely does not belong to the southwest burial ground.

Grave field south: This grave field is located south of the camp area and extends from Frauentorgasse along the railway line to the city park. So far, its north-western boundary has been recorded. It should include well over 300 burials, with both earth and stone slab graves and brick slab or masonry shaft graves were observed. The graves can be dated from the beginning of the 4th to the first half of the 5th century. According to the information from Vita Sancti Severini about the stationing of Germanic federal troops in Tulln, suitable finds were also unearthed in this cemetery.

In the east of the camp, six body graves facing west-east have been discovered in the area of Lazarettgasse. Presumably, this is another cemetery along the arterial road from the porta principalis dextra to the east (cemetery east). The graves allow a dating of these graves in the 2nd / 3rd centuries. Century.

Limes Street

The Reichsstraße, a street of the first order, connected Carnuntum with Lauriacum and led through the Tullnerfeld in the course of today's Maria Gugging - St. Andrä - Zeiselmauer street . The further course was probably past the Nitzinger milestone and on via Michelhausen through the Perschlingtal to Cetium (St. Pölten).

The Roman milestone on the Nitzinger Feld was erected in AD 217/218 and first mentioned in literature in 1324. A connecting road of the second or third order must be accepted from the Nitzingen milestone to Comagenis.

As part of the construction work at Tullner Kirchengasse 10, a round milestone almost two meters high was discovered and first stored in a gravel pit near Muckendorf , but then by the Königstetten pastor Dr. Schrattbauer recovered and placed in the vestibule of his St. Jakob church. The well-preserved inscription indicates the distance a Cetio Milia Passuum XXIII , which would exactly match the site. The milestone is dated to the year 235/239 AD, the reign of Gaius Iulius Verus Maximinus ( Maximinus Thrax ).

Another milestone from the years 217-218, the reign of Emperor Macrinus and his son Caesar Diadumenianus , was discovered in 1998 at common barons . A year later, another milestone from the year 313, the reign of Emperor Licinius , was recovered from the same site .

The west exit road of the warehouse could be located in the area of Ländgasse. Their escape is reflected in today's Albrechtgasse. The course of the road then led from Comagena to Zwentendorf and Traismauer .

Monument protection and remains

All of the facilities described here are ground monuments within the meaning of the Monument Protection Act . Subsequent excavations and targeted collection of artefacts and finds without the approval of the Federal Monuments Office are a criminal offense. Accidental finds of archaeological objects (walls, ceramics, metal, bones, etc.), as well as all measures affecting the ground, must be reported to the Federal Monuments Office.

The exposed and preserved remains of the wall of the Porta principalis dextra are exhibited in a specially built museum in the garden of the former state hospital. Behind the gate is the Roman Museum Tulln in the restored former hospital building , where numerous stone reliefs and small finds are exhibited.

Directly on the banks of the Danube is the so-called salt tower, the horseshoe tower on the western flank of the camp that has largely been preserved in its ancient structure.

A Roman grave lion is visibly walled in in the south tower of the Tulln parish church.

See also

literature

- Gertrud Pascher: Roman settlements and roads in the Limes area between Enns and Leitha. In: The Roman Limes in Austria 19, 1949, p. 138 ff .; 189 ff.

- Otto Biack: History of the city of Tulln. Self-published by the municipality of Tulln, Tulln 1982.

- Kurt Genser: The Austrian Danube Limes in Roman times. A research report. In: The Roman Limes in Austria 33 (1986), p. 356 ff.

- Manfred Kandler, Hermann Vetters (ed.): The Roman Limes in Austria. A guide. Publishing house of the Austrian Academy of Sciences, Vienna 1989, ISBN 3-7001-0785-4 . P. 153 ff.

- Barbara Wewerka u. a .: Tulln urban archeology II. New results on urban archeology in Tulln. Excavations by the ASINOE association from 1991–1997 (= communications from the local history working group for the city and district of Tulln 11). Local history working group for the city and district of Tulln, Tulln 1997.

- Herwig Friesinger, Fritz Krinzinger (Hrsg.): The Roman Limes in Austria. Guide to the archaeological monuments. Publishing house of the Austrian Academy of Sciences, Vienna 2002, ISBN 3-7001-2618-2 , p. 226 ff.

- Georg Fleischmann: The Roman Tulln (Comagena). Dissertation University of Vienna, 2003.

- Hannsjörg Ubl: The Noric Provincial Army of the Princely Period as reflected in the new finds of diplomas and inscriptions. In: Zsolt Visy (ed.): Limes XIX. Proceedings of the XIXth International Congress on Roman Frontier Studies held in Pécs, Hungary, Sept. 2003. University of Pécs 2005. pp. 107-118.

- René Ployer: The Norwegian Limes in Austria. Find reports from Austria Materialhefte series B, Volume 3, Vienna 2013, ISSN 1993-1263 , p. 84 ff.

- Helga Sedlmayer: Tulln on the Danube - Comagenis. Fort - vicus. In: Verena Gassner, Andreas Pülz (Hrsg.): The Roman Limes in Austria. Guide to the archaeological monuments. Publishing house of the Austrian Academy of Sciences, Vienna 2015, ISBN 978-3-7001-7787-6 , pp. 229–233.

- Kira Lappe: Nitzing - milestone. In: Verena Gassner, Andreas Pülz (Hrsg.): The Roman Limes in Austria. Guide to the archaeological monuments. Publishing house of the Austrian Academy of Sciences, Vienna 2015, ISBN 978-3-7001-7787-6 , pp. 233-234.

- Friedrich Lotter: Displacements of peoples in the Eastern Alps-Central Danube region between antiquity and the Middle Ages: (375–600), Walter de Gruyter, Berlin, New York, 2003.

Web links

- Location of the fort on Vici.org

- The Roman Limes in Austria

- Animated film of the Roman Limes in Tullnerfeld

- Tulln Roman Museum

- Austrian City Atlas: History of the City of Tulln

Remarks

- ↑ Georg Fleischmann: The Roman Tulln (Comagena) , dissertation University of Vienna 2003, p. 244 ff.

- ↑ Kurt Genser: The Austrian Danube Limes in Roman times. A research report , In: The Roman Limes in Austria 33 (1986), p. 357.

- ↑ Kurt Genser: The Austrian Danube Limes in Roman times. A research report . In: The Roman Limes in Austria 33 (1986), p. 370.

- ↑ Tabula Peutingeriana IV, 1.

- ^ Itinerarium Antonini 234, 1.

- ^ Itinerarium Antonini 248, 3.

- ↑ Notitia dignitatum Occidentis 5, 110, 260; Occidentis 7, 59.

- ↑ a b Notitia dignitatum Occidentis 34, 36.

- ↑ a b Notitia dignitatum Occidentis 34, 42.

- ^ Vita Sancti Severini 1, 3; 3, 1; 33, 1.

- ↑ CIL 3, 5650 .

- ↑ AE 2003, 1319 ; Herwig Friesinger, Fritz Krinzinger (Hrsg.): The Roman Limes in Austria. Guide to the archaeological monuments . Publishing house of the Austrian Academy of Sciences, Vienna 2002, ISBN 3-7001-2618-2 , p. 226 ff.

- ↑ Manfred Kandler, Hermann Vetters (ed.): The Roman Limes in Austria. A leader . Publishing house of the Austrian Academy of Sciences, Vienna 1989, ISBN 3-7001-0785-4 , p. 157.

- ↑ A. Kerschbaumer: History of the City of Tulln , Krems 1902, p. 29 with notes 2-3.

- ↑ Erich Polaschek: Tulln in Roman times. In: Heimat-Kalender des Tulln District , Tulln 1952, p. 116.

- ^ Hannsjörg Ubl: The Limes Museum , in Tulln museums in the Minorite Monastery. Catalog of the permanent collection , Tulln 1996, pp. 115 and 117; Hannsjörg Ubl: The sculptures of the urban area of Aelium Cetium . CSIR Austria I, 6, Vienna 1979, pp. 63-64 u. Pp. 70-71.

- ↑ A. Dungel: Roman finds in Tulln and the surrounding area , In: Mittheilungen der kk Centralcommission 16, 1871, CVII ff.

- ↑ MA Niegl: The archaeological research of the Roman period in Austria. (= Memoranda of the Austrian Academy of Sciences, Philological-Historical Class 141) Vienna 1980.

- ↑ J. Oehler: Die Römer in Niederösterreich , in: 21st Annual Report of the Girls' Obergymnasium Vienna VI, Rahlgasse 4 , 1912/13, p. 3 ff.

- ↑ Otto Biack: history of the city Tulln , 1982, pp 46-47; Manfred Kandler, Hermann Vetters (ed.): The Roman Limes in Austria. A leader . Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, Vienna 1989, ISBN 3-7001-0785-4 , pp. 159–160; Hannsjörg Ubl: The new milestones and the Noric Limes Road. In: Find reports from Austria 37 (1998), pp. 183–188.

- ↑ Erich Polaschek: Tulln in Roman times . In: Heimatkalender des Tulln district , Tulln 1952, p. 108 ff.

- ↑ Heinrich Zabehlicky: The body graves of late antiquity and migration times from the Noric part of Lower Austria , Dissertation Vienna 1976, pp. 224, 228-229, 431.

- ↑ Otto Biack, A. Kerschbaumer: Geschichte der Stadt Tulln , 1966, pp. 191–192; Otto Biack: History of the City of Tulln , 1982, pp. 208-209.

- ^ Gertrud Pascher: Roman settlements and roads in the Limes area between Enns and Leitha . In: The Roman Limes in Austria 19 (1949), pp. 154–155.

- ↑ Otto Biack: Tulln . In: Fund reports from Austria 5 (1946–1950), pp. 114, 178, 234–235; Otto Biack: Tulln. In: Find reports from Austria 7 (1956–1960), p. 112; Otto Biack: Tulln . In: Find reports from Austria 8 (1961–1965), p. 103; Otto Biack: Roman finds in the Tullner district . In: Heimatkalender des Tulln district , Tulln 1952, p. 122 ff.

- ↑ Otto Biack: history of the city Tulln , 1982, p 47th

- ^ Robert Göbl: Römischer Münzhort Tulln 1966 , In: Numismati Journal 83 (1969), pp. 56-57.

- ↑ Otto Biack, Herma Stiglitz-Thaller: Tulln . In: Find reports from Austria 6 (1951–1955), p. 101.

- ↑ Herma Stiglitz-Thaller: Tulln . In: Find reports from Austria 8 (1961–1965), p. 103.

- ↑ Georg Fleischmann: The Roman Tulln (Comagena) . Dissertation University of Vienna 2003, p. 209 ff.

- ↑ CIL 17-04-01, 00076 ; Herma Stiglitz-Thaller: Tulln . In: Find reports from Austria 9 (1966–1970), pp. 139–140.

- ^ Hannsjörg Ubl: Tulln . In: Find reports from Austria 9 (1966–1970), p. 289.

- ^ Hannsjörg Ubl: Tulln . In: Find reports from Austria 13 (1974), pp. 163–164; Hannsjörg Ubl: Tulln . In: Find reports from Austria 15 (1976), pp. 277–278.

- ↑ J. Köstlbauer: Tulln. In: Find reports from Austria 17 (1978), p. 359.

- ↑ A. Kabiersch: The Romans in Tulln . In: Kulturberichte Niederösterreich , September 1980, pp. 1 ff.

- ^ Hannsjörg Ubl: Comagena camp excavation (Tulln) . In: PAR 30 (1980), pp. 22-23; Hannsjörg Ubl: Tulln . In: Find reports from Austria 19 (1980), pp. 549-550; Hannsjörg Ubl: The exposure of the porta principalis dextra of the Alenlager Comagena (Tulln). In: Mitteilungen der Gesellschaft der Freunde Carnuntums 2 (1981), p. 24 ff.

- ↑ Hannsjörg Ubl, in: Peter Scherrer (Ed.): Files from the 3rd Austrian Archaeological Conference in Innsbruck. 3rd to 5th April 1987 , 1989, p. 89.

- ↑ Georg Fleischmann: The Roman Tulln (Comagena). Dissertation University of Vienna 2003, p. 194 ff.

- ↑ a b Herwig Friesinger, Fritz Krinzinger (ed.): The Roman Limes in Austria. Guide to the archaeological monuments. Verlag der Österr. Academy of Sciences, Vienna 2002, ISBN 3-7001-2618-2 , p. 228.

- ^ Find reports from Austria 39 (2000), pp. 35–36.

- ↑ a b Homepage of the Federal Monuments Office, Monument of the Month / 2000 / November, http://www.bda.at/text/136/1005/5528 in the version of August 25, 2009.

- ↑ R. Dragan, Archaeological Studies in Tulln, Ländgasse 5 . In: Find reports from Austria 42 (2003), pp. 503-510.

- ↑ . Breibert W., Th Kreitner, O. Schmitz Berger, U. Zimmermann: Roman road of tombs and medieval artisans' quarter on the banks of the Danube. Preliminary report on the archaeological investigations 2005/06 in Schießstattgasse in Tulln . In: Find reports in Austria 45 (2006), pp. 590–620

- ↑ Martin Krenn, in: Find reports from Austria 46 (2007), p. 36.

- ^ Hannsjörg Ubl: Comagena camp excavation (Tulln). In: Pro Austria Romana 30 (1980), p. 23.

- ^ Hannsjörg Ubl: Tulln, Zeiselmauer, Klosterneuburg. New research results on three auxiliary troop camps in the Noric-Pannonian border area of the Austrian Limes section. In: Römisches Österreich 13/14 (1985/86), pp. 295–296.

- ^ Hannsjörg Ubl: Comagena camp excavation (Tulln). In: Pro Austria Romana 30 (1980), pp. 22-23.

- ↑ Hannsjörg Ubl: The exposure of the porta principalis dextra of the Alenlager Comagena (Tulln) , in: Mitteilungen der Gesellschaft der Freunde Carnuntums 2 (1981), p. 23.

- ↑ Wolfgang Pietsch: A typology of the storage and fort towers on the Noric and Pannonian Limes. Dissertation, Vienna 1993, pp. 22-23.

- ↑ Manfred Kandler, Hermann Vetters (ed.): The Roman Limes in Austria. A leader . Publishing house of the Austrian Academy of Sciences, Vienna 1989, ISBN 3-7001-0785-4 , p. 158.

- ^ Georg Fleischmann: The Roman Tulln (Comagena) , dissertation University of Vienna 2003, p. 242.

- ↑ Barbara Wewerka u. a .: Tulln urban archeology II. New results on urban archeology in Tulln. Excavations by the ASINOE association from 1991–1997 (= communications from the local history working group for the city and district of Tulln. 11). Local history working group for the city and the district of Tulln, Tulln 1997, pp. 29–30.

- ↑ Margit Bachner u. a .: Kerschbaumergasse . In: Barbara Wewerka u. a .: Tulln urban archeology II. New results on urban archeology in Tulln. Excavations by the ASINOE association from 1991–1997 (= communications from the local history working group for the city and district of Tulln. 11). Local history working group for the city and district of Tulln, Tulln 1997, pp. 24–25.

- ^ Hannsjörg Ubl: Tulln - Comagena. In: Herwig Friesinger, Fritz Krinzinger (Hrsg.): The Roman Limes in Austria. Guide to the archaeological monuments . Verlag der Österr. Academy of Sciences, Vienna 2002, ISBN 3-7001-2618-2 , p. 228.

- ^ Georg Fleischmann: The Roman Tulln (Comagena) , dissertation University of Vienna 2003, p. 234.

- ↑ Wolfgang Pietsch: A typology of the storage and fort towers on the Noric and Pannonian Limes. Dissertation, Vienna 1993, p. 177; Hannsjörg Ubl: Tulln, Zeiselmauer, Klosterneuburg. New research results on three auxiliary troop camps in the Norico-Pannonian border area of the Austrian Limes section. In: Römisches Österreich 13/14 (1985–1986), pp. 293–322.

- ↑ Hannsjörg Ubl: The exposure of the porta principalis dextra of the Alenlager Comagena (Tulln) , in: Mitteilungen der Gesellschaft der Freunde Carnuntums 2 (1981), p. 24 ff.

- ↑ M. Neubauer: The boundary of the Roman camp Comagena in Tulln. In: Local history working group for the city and the district of Tulln. Communications 6 (October 1989), p. 6.

- ↑ Georg Fleischmann: The Roman Tulln (Comagena) , dissertation University of Vienna 2003, pp. 235–236.

- ↑ H. Winterleitner: rescue excavation in the main sports school in Tulln , in: Fund reports from Austria 30 (1991), p. 48 ff .; Martin Krenn u. a .: Archaeological investigations in the area of the sports school in Tulln, Lower Austria. In: Find reports from Austria. 32 (1993), p. 171 ff.

- ↑ Martin Krenn et al .: Hauptschule Wienerstrasse - "Sports Main School" in Tulln City Archeology II. New results on city archeology in Tulln. Excavations of the ASINOE association from 1991–1997 , in: Mitteilungen des Heimatkundlichen Arbeitskreis für die Stadt und den Bezirk Tulln 11 (1997), pp. 12–23.

- ^ Margit Bachner et al .: Kerschbaumergasse in Tullner Stadtarchäologie II. New results on urban archeology in Tulln. Excavations by the ASINOE association from 1991–1997 , in: Mitteilungen des Heimatkundlichen Arbeitskreis für die Stadt und den Bezirk Tulln 11 (1997), pp. 24–28.

- ↑ J. Köstlbauer, Tulln , in: Find reports from Austria 17 (197) 8, p. 359.

- ↑ Barbara Wewerka: The excavation work in Tulln - Ländgasse , in: Find reports from Austria 31 (1992), p. 116 ff .; Norbert Hirsch: The Tulln excavation - Ländgasse 1994/95 , in: Find reports from Austria 34 (1995), p. 385 ff.

- ↑ Barbara Wewerka et al .: Ländgasse, excavation 1991/92 and 1994/95 , in: Barbara Wewerka u. a .: Tulln urban archeology II. New results on urban archeology in Tulln. Excavations by the ASINOE association from 1991–1997 (= communications from the local history working group for the city and district of Tulln. 11). Local history working group for the city and the district of Tulln, Tulln 1997, pp. 29–37.

- ↑ Ubl 1989, p. 89.

- ↑ Georg Fleischmann: The Roman Tulln (Comagena) , dissertation University of Vienna 2003, p. 214 ff.

- ↑ Herma Stiglitz, The Roman Donaukastell Zwentendorf in Lower Austria (the excavations 1953–1962) . In: The Roman Limes in Austria 26 (1975), p. 69, note 43.

- ↑ G. Moßler, Tulln , in: Fund reports from Austria 8 (1961–1965), p. 103, Georg Fleischmann: Das roman Tulln (Comagena) , dissertation University of Vienna 2003, p. 191 ff.

- ↑ H. Hübl, report on the archaeological investigations in the courtyard of secondary school II / III in Tulln in October 1989 . In: Local history working group for the city and the district of Tulln. Mitteilungen 7 (February 1990), pp. 2-4, Erik Szameit, The late Roman fan tower from Tulln. In: Tulln museums in the Minorite monastery. Catalog of the permanent collection , Tulln 1996, pp. 191–196.

- ↑ The Roman Limes in Austria .

- ↑ Hannsjörg Ubl: 2005, p. 110.

- ↑ Erich Polaschek: Two stone monuments in Tulln near Vienna , in: Annual Issues of the Austrian Archaeological Institute 39, 1952, supplement p. 69 ff.

- ↑ Erich Polaschek: Tulln in Roman times. In: Home calendar of the Tulln district , Tulln 1952, p. 113.

- ↑ Hannsjörg Ubl: 2005, p. 110

- ↑ AE 2003, 01319 ; Homepage Federal Monuments Office: Building inscription from the Roman equestrian camp Comagena Lower Austria, Tulln

- ↑ Erich Polaschek: Tulln in Roman times. In: Home calendar of the Tulln district. Tulln 1952, p. 108 ff.

- ↑ Erich Polaschek: Tulln in Roman times , in: Heimatkalender des Tullner District , Tulln 1952, p. 115.

- ^ Eugippius: Vita Sancti Severini , Chapter 1, 3, 33, F. Lotter 2003, p. 113.

- ↑ Barbara Wewerka u. a .: Tulln urban archeology II. New results on urban archeology in Tulln. Excavations by the ASINOE association from 1991–1997 (= communications from the local history working group for the city and district of Tulln 11). Local history working group for the city and the district of Tulln, Tulln 1997, pp. 101-102.

- ↑ Barbara Wewerka u. a .: Tulln urban archeology II. New results on urban archeology in Tulln. Excavations by the ASINOE association from 1991–1997 (= communications from the local history working group for the city and district of Tulln. 11). Local history working group for the city and the district of Tulln, Tulln 1997, pp. 82–83.

- ↑ Barbara Wewerka u. a .: Tulln urban archeology II. New results on urban archeology in Tulln. Excavations by the ASINOE association from 1991–1997 (= communications from the local history working group for the city and district of Tulln 11). Local history working group for the city and the district of Tulln, Tulln 1997, p. 50. 54.

- ↑ Barbara Wewerka u. a .: Tulln urban archeology II. New results on urban archeology in Tulln. Excavations by the ASINOE association from 1991–1997 (= communications from the local history working group for the city and district of Tulln. 11). Local history working group for the city and the district of Tulln, Tulln 1997, p. 86 ff.

- ↑ Barbara Wewerka u. a .: Tulln urban archeology II. New results on urban archeology in Tulln. Excavations by the ASINOE association from 1991–1997 (=. Communications from the local history working group for the city and district of Tulln. 11). Local history working group for the city and the district of Tulln, Tulln 1997, p. 55.

- ↑ Martin Krenn, in: Fund reports from Austria 46 (2007), pp. 34–35.

- ^ Norbert Hirsch, in: Find reports from Austria 41 (2002), p. 388 ff.

- ^ Martin Krenn in: Find reports from Austria 46 (2007), pp. 35–36.

- ↑ http://www.bda.at/events/3/5905

- ↑ Otto Biack: history of the city Tulln , 1982, p 47th

- ↑ Scholz et al .: Urban Archeology - From ancient Comagenis to today's Tulln. In Archeology Austria 18/2, 2007, pp. 4-18.

- ↑ Richard Hübl: Roman Tulln. The ancient Comagenis. Local history working group for the city and district of Tulln, Tulln 2004.

- ↑ Scholz et al .: Urban Archeology - From ancient Comagenis to today's Tulln. In Archeology Austria 18/2, 2007, pp. 6-7.

- ↑ Martin Krenn in: Find reports from Austria 46 (2007), p. 34.

- ↑ Scholz u. a .: Urban archeology - from ancient Comagenis to today's Tulln. In: Archeology Austria 18/2 (2007), p. 6 ff.

- ↑ a b Martin Krenn in: Find reports from Austria 46 (2007), p. 41.

- ^ Twelve tables law in Cicero, de legibus 2, 23, 58.

- ↑ Wolfgang Breibert: Roman grave route and medieval handicraft quarter on the banks of the Danube. Preliminary report on the archaeological investigations 2005/06 in Schießstattgasse in Tulln. In: Find reports from Austria 45 (2006), p. 590 ff .; in: Find reports from Austria 46 (2007), p. 34.

- ↑ Peter Trebsche in: Find reports from Austria 45 (2006), p. 39.

- ↑ Herwig Friesinger, Fritz Krinzinger (ed.): The Roman Limes in Austria, guide to the archaeological monuments . Publishing house of the Austrian Academy of Sciences, Vienna 2002, ISBN 3-7001-2618-2 , p. 229.

- ↑ Barbara Wewerka u. a .: Tulln urban archeology II. New results on urban archeology in Tulln. Excavations by the ASINOE association from 1991–1997 (=. Communications from the local history working group for the city and district of Tulln. 11). Local history working group for the city and the district of Tulln, Tulln 1997, p. 55 ff. And p. 102.

- ↑ a b Gertrud Pascher: Roman settlements and roads in the Limes area between Enns and Leitha . In: The Roman Limes in Austria 19 (1949) pp. ??.

- ↑ CIL 3, 13534 .

- ↑ CIL 17-04-01, 00076

- ↑ Herma Stiglitz in: Find reports from Austria 9 (1966/1970), pp. 139–140.

- ^ Hannsjörg Ubl: The new milestones and the Noric Limes road. In: Find reports from Austria 37 (1998), p. 186; CIL 17-04-01, 00077 .

- ↑ CIL 17-04-01, 00078 .

- ↑ Barbara Wewerka u. a .: Tulln urban archeology II. New results on urban archeology in Tulln. Excavations by the ASINOE association from 1991–1997 (= communications from the local history working group for the city and district of Tulln 11). Local history working group for the city and the district of Tulln, Tulln 1997, pp. 101-102.