Klosterneuburg Castle

| Klosterneuburg Castle | |

|---|---|

| Alternative name |

a) Quadriburgium ?, b) Arrianis ? |

| limes | Upper Pannonia |

| section | Route 2 |

| Dating (occupancy) |

late Flavian , up to 5th century AD |

| Type |

a) Cohort fort, b) Alenkastell |

| unit |

a) Cohors I Montanorum b) Cohors II Batavorum c) Cohors I Aelia (Severiana) sagittariorum d) Equites promoti ? e) Gens Marcomannorum ? |

| size | about 2.2 ha, width 110 m |

| Construction |

a) Wood and earth fort b) Stone fort , square complex with rounded corners, surrounded by two pointed trenches, extensive adaptations in late antiquity |

| State of preservation | ground monument no longer visible above ground |

| place | Klosterneuburg |

| Geographical location | 48 ° 18 ′ 18 ″ N , 16 ° 19 ′ 30 ″ E |

| Previous | Fort Zeiselmauer (west) |

| Subsequently | Legion camp Vindobona (east) |

The Klosterneuburg fort was a military camp in the Roman fortress chain of the Danube Limes . It belonged to the western part of the Pannonian Limes, in which it was in turn the camp furthest to the west. Its remains are in today's municipality of Klosterneuburg in the Tulln district of the Austrian state of Lower Austria .

In its early days, the fort served as a cohort camp for auxiliary troops ( auxilia ) and, from the 2nd century AD, it was the base of a cavalry unit . Its actual ancient name was unknown until recently due to a lack of sources. Today the warehouse area is almost completely built over by Klosterneuburg Abbey and residential buildings in the old town. The fortress went through several renovation phases and was used from the 1st to the late 5th century. The crew's task was to monitor a Danube crossing and the Limes road from Vindobona to Lauriacum . A civil settlement ( vicus ) and a burial ground were discovered in the vicinity of the fort .

In addition to the fort, this article also deals with two watchtowers suspected at Maria Gugging and Greifenstein .

location

The city of Klosterneuburg is located around 13 km west of the federal capital Vienna , on the right bank of the Danube, above the Danube gorge between Leopoldsberg and Bisamberg . In the north and east it is bordered by the alluvial forests of the Danube. The foothills of the mountain slopes of the Vienna Woods connect to the south and west:

- Leopoldsberg,

- Kahlenberg ,

- Buchberg,

- Eichberg and

- Freiberg.

Before it was discovered, the fort was presumed to be in a wide variety of places such as B. at Stockerau , which is on the left bank of the Danube. Joseph Aschbach and Friedrich von Kenner believed that it was identical to Zeiselmauer . For Maximilian Fischer, on the other hand, the location in the upper town seemed extremely well suited for military purposes and as a local trading post for the tribes on the other side of the Danube. Friedrich von Kenner finally came to the conviction, not least because of the discovery of a military diploma from the time of Emperor Titus, that

- "... a small camp of the Cohors I Montanorum was located at the place of discovery, which was under the command of the Pannonian legate".

As the finds in this area increased more and more, Karl Drexler took

- "... the direction of the cardo towards today's mountain road, while the decumanus extended from the ravine at the Gertrudskirche towards the Hundskehle".

Even Edward Nowotny always suspected it in the upper town, trying to pull out of the 1925 cadastral plan of the monastery conclusions about the layout of the fort. For him it was unlikely that the fort should be in the lower town. Nowotny therefore marked out a fort area in the upper town, for which he took that of Eferding / Upper Austria as a model:

- Northwest front: Stiftskellergarten,

- Northeast side: collegiate church,

- South-east front: Upper main square at the house front in the NE,

- South-west side: Leopoldgasse and continuation to the Hundskehle.

With these dimensions Nowotny came to an area of 540 x 640 Roman feet, which came very close to that of Eferding. It also corresponded to the one in Weißenburg in Bavaria , whose fort was also designed for a cohors milliaria equitata (1000 men strong, partially mounted unit).

Today we know that the fort is located under the oldest part of the city, the monastery area in the "Upper Town", a rocky terrace between the banks of the Danube and the foot of the Buchberg. This is limited to the north by the Kierlingbach and to the south by the Weidlingbach . The Limes Road, which once came up from Vindobona from the south, did not cross the camp, but ran directly past the Buchberg. Then it turned west into the Kierlingtal and continued from there to Noricum . The provincial border between Pannonia and Noricum probably also ran in the Kierling Valley . It may have been to the west of today's Maria Gugging (see below). Based on the brick stamps found on site, it is clear that this fort belonged to the administrative area of the province of Pannonia.

Surname

In written ancient sources there are no precise references to the ancient name of Klosterneuburg. Even later investigations were unable to bring the different views on the ancient name of Klosterneuburg to a common denominator. While there seem to be no more doubts as to whether Klosterneuburg belongs to the province of Pannonia , its Roman name remained controversial until recently. Suggested are u. a. the names Asturis, Cannabiaca, Quadriburgium or Arrianis , with Arrianis being given preference in recent times .

If an attempt was initially made to equate the fort with the Citium post office (near Tulln ) mentioned in the Tabula Peutingeriana , the ancient Klosterneuburg was identified with Asturis from Theodor Mommsen . This name probably comes from a Roman army detachment that was set up in the Asturias region on the north coast of Spain . After Wilhelm Kubitschek also announced Klosterneuburg as "allegedly Astura", it was, besides Herma Stiglitz and Hannsjörg Ubl, above all Eduard Zenker who meticulously dealt with the question of the name of the ancient Klosterneuburg.

Research history

18th and 19th centuries

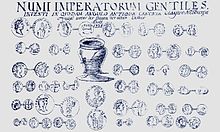

According to Maximilian Fischer, the first reports of Roman finds from Klosterneuburg come from Benedict Prill . He noted, among other things, that during the construction of the baroque Neustift in 1736, when the old chancellery and its "mail tower" were removed, a vessel with Roman silver coins from the time of Gaius Iulius Caesar to Emperor Decius had been discovered. When the so-called old barracks were built at the beginning of the 19th century, coin finds were made again. Graves were probably also uncovered during this construction work. In 1834 three stones with inscriptions came to light during the renovation of the monastery courtyard. After the copy by Maximilian Fischer, they were walled up again. The expansion of the so-called Ernestine tract in the years 1834–1842 brought a large number of finds. Numerous late antique brick stamps of the OFARN group with the inscription "OFARNVRSICINIMG" were recovered here. The stamps of the Magister figlinarum Ursicinus were shipped to the Pannonian province of Valeria and were found there not only on the never completed Göd-Bócsaújtelep fort but also on Ländeburgi such as Dunakeszi . The OFARN stamps can be dated to the time of the rule of Emperors Constantius II (337–361) and Valentinian I (364–375). Since the stamp abbreviations AR , ARN and ARAN cannot be clearly explained for the time being, the previous translation suggestions remain speculative. A votivara ( dedicatory inscription for gods) by Quintus Attius and a tablet with the inscription “Q. Aelii Valentis opus ”. In addition, Roman remains of walls and bricks could be observed. One of the most interesting Roman finds, however, was made on July 23, 1838. From the rubble of the foundation work behind the main apse of the collegiate church, some bronze fragments were found. They were put back together by E. Stoy and turned out to be a Roman certificate of discharge ( military diploma ) from the time of Titus (June 13, 80 AD).

20th century

These Roman finds, recurring again and again, prompted mainly men from the circle of Viennese antiquity research to become active in Klosterneuburg. Above all, Friedrich von Kenner , Wilhelm Kubitschek and Emil Polaschek should be mentioned here. According to their reports, when the Stiftskeller was expanded in 1904, Roman walls were cut and bricks and a coin from the time of Valentinan I were recovered. Allegedly some ancient body and cremation graves were found before 1936, but destroyed in the process. A pot container from the 1st or 2nd century AD is also known of found objects.

At the end of May 1953, scientific excavations were carried out on the fort area for the first time on the initiative of the Federal Monuments Office and under the direction of Karl Oettinger . Originally, their aim was only to research the palace palace of the Babenbergs and especially their palace chapel ( Capella Speciosa ). But after they came across Roman building remains, the Austrian Archaeological Institute (Herma Stiglitz, Adelheid Schmeller and Rudolf Egger) was brought in. The excavation team was able to uncover a late antique grave building ( Cella memoriae ) on the Stiftsplatz - in the area of the Capella Speciosa . Inside the capella there was also a multi-room complex with three round apses (apse = semicircular porch, later interpretation as balineum / camp bath, see below). To the south-east of this building, a “flat apsid building” with a U-shaped floor plan was uncovered, which Hannsjörg Ubl later interpreted as a late antique “horseshoe tower” (tower protruding from the defensive wall with rounded, front-sided basket arch, see also below) from stone period II of the camp has been. Remains of the wall from the previous building (a rectangular intermediate tower) were still located under this. The two building structures were obviously also aligned with the south-eastern fort wall running along there (orientation from north-west-south-east).

In the 1960s, parts of the V-shaped trenches, remnants of the fort wall and, again and again, burial places with grave goods were found.

In the Upper Town, the district around Buchberg-, Raffael-Donner-, Jahn- and Franz-Rumpler-Gasse has always been assumed to be the area of the Roman burial ground of Klosterneuburg and has been confirmed by various finds. In the course of the investigations in the 1970s, the so-called flat apse building uncovered in the excavations in 1953/54 in the area of the Capella Speciosa was reinterpreted and recognized as a late antique horseshoe tower, the square wall remains below it as its older predecessor (inner tower) (see below) .

In the 1980s, in the north-west corner of the cloister, in addition to a late antique oven, the remains of barracks from the first stone warehouse (stone period I) were found. In order to be able to bring interested visitors to the monastery closer to the Roman past of this place, it was planned to cover the excavation with a concrete ceiling. The building remains underneath should be preserved and the site made accessible to everyone. During an emergency excavation carried out in Buchberggasse 3b in 1991, parts of a Roman burial ground were discovered again. To the north of this property, a grid square of 14.5 × 11 m was searched. The ancient horizon was already encountered at a depth of only 80 cm. Ruts and the finds in the lateral water drainage ditches confirmed the existence of the south-western arterial road from the fort, which presumably continued from there via the “Black Cross” into the Weidling Valley.

In 1994 the moat of the fort could be cut again. Numerous finds have been made in its backfill. The moat was there 2.5 m deep and 2 m wide. In addition, in a rescue excavation by the Federal Monuments Office (Hannsjörg Ubl), the "three-apse building" (the camp bath) could be re-measured. Ubl also suspected dense Roman buildings from the early and middle imperial period under the Stiftsplatz. In 1998, a building at Leopoldstrasse 17 was cleared for demolition. The Federal Monuments Office was able to recover and secure in a layer of humus, in addition to typical Roman finds such as ceramics and terra sigillata shards , including the fragment of a scale armor (Latin: Lorica Squamata ). In 1999, about 1.85 m below today's street level, a two-meter-wide stone layer was excavated from rubble stones on gravel. In a new investigation in 2000, the stone layer was identified as the massive substructure of a road.

21st century

From 2000 to 2003, among other things, the excavations on Rathausplatz were resumed (Federal Monuments Office, Johannes-Wolfgang Neugebauer ). At a depth of 2.6 m, the Roman street already observed in 1999 was cut again. The five-meter-wide paving was bordered on both sides by ditches and was once the connecting path between the western fort gate and the route of the Limes road that ran along the Buchberg. In ancient times, this area (corresponds to today's Markgasse) was traversed by a stream and was heavily dampened, which made a massive substructure for the road necessary. The Federal Monuments Office (Hannsjörg Ubl) created a search cut in Albrechtsgasse 4–6, the former forge of the monastery (Parz. 192/4). The aim was to explore the south wall of the fort and the extent of the medieval residence of the Babenbergs . In 2001 a search cut of up to 4.7 m was dug at right angles to the monastery buildings. Here the two pointed trenches showed again in profile. In 2002 Hannsjörg Ubl's excavation in the forge was expanded to include the Dechanteihof. A wall running to the northeast-southwest could be encountered, which was about one meter lower on Roman foundations. This quarry stone masonry with a lime mortar bond was part of a corner tower of the former stone period I fort, which had a total of two construction phases. No traces of the wood-earth store were found. The 90 cm wide southern fort wall ran in a quarter of a circle, the corners of the stone fort were rounded in the classic manner. The corner tower attached within the wall had a rectangular floor plan. At a later time, a fan-shaped tower was added to the corner of the camp, which could be dug up to its junction with the wall.

development

Leopoldsberg and Simonsberg were settled towards the end of the Neolithic . Litter finds from the Neolithic indicate that settlements also existed in the narrower urban area (Stiftsplatz, Josef-Brenner-Straße). In the Bronze Age there was a fortification with ramparts and graves on the Kumenberg near St. Andrä, which was probably inhabited until the Middle Ages. Settlement remains from the Urnfield Period (1200–700 BC) were found in the monastery area (Jungherrengarten), near St. Gertrud and in Martinstrasse. Finds from the Kierlingtal prove that this path was already used back then. In the 1st century AD, a border fort was built by the Romans in the upper town. His crew was entrusted with the blocking and monitoring of an important thoroughfare that ran through the Kierlingtal over the Hadersfelder Berg to the Greifensteiner Sporn. Subsequently, it also secured the western glacis (apron) of Vindobona , the Limes road from Carnuntum to Lauriacum , two important legionary camps and a Danube crossing that connected to the road leading up from Oberleiser Berg on the north bank.

After various reconstructions in the fort by early and middle imperial units in the 1st - 3rd centuries, the border defense on the Danube was reorganized in the early 4th century. The garrison troops in Klosterneuburg were now part of the border troops, the so-called Limitanei or Ripenses . At the end of the 4th or beginning of the 5th century, the troops, which were increasingly amalgamated in terms of personnel due to civil wars, Germanic incursions and assignments to the mobile units of the field armies, the Comitatenses , finally left most of the camp area to the civilian population. This turned into a civil, fortified village (oppidum) . The excavations of 1953/1954 and 1977 produced rich finds from the late Roman period and thus the evidence that the entire camp area was still inhabited at the time of Severin's arrival . In order to fill the gaps in the army, more and more tribal associations from the Barbaricum (settlement area of the free Germanic tribes on the left of the Danube) were allowed to settle as federates (allies) south of the Danube in order to take over the border defense of the empire there. This also happened in Klosterneuburg, where, among other things, the primitive mud huts of the new settlers (presumably Donausueben or Marcomanni ) can be identified as the last ancient discovery horizon. Coins were still in circulation until the reign of the Western Roman Emperor Honorius (395–423). Most of the Romanes (locals who lived the Roman way) of Klosterneuburg probably emigrated to Italy in 488 on the orders of Odoacer . Towards the end of the 5th century, the mud huts also burned down. The fort and the monastery plateau were obviously abandoned and abandoned after evaluating small finds. Contrary to earlier assumptions, no settlement continuity could be established through recent excavations, no traces of human activities during the 8th and 9th centuries were found. According to previous knowledge, resettlement on a large scale did not take place again until the High Middle Ages, in the 10th or more likely in the 11th century. The founder of Klosterneuburg Monastery, Margrave Leopold III. , found a settlement in the ruins of the fort when he decided to build his residence here. Archaeological studies have shown that Roman ashlars were also used in the construction of the Babenbergerburg.

Fort

The fortification extended in a narrow, precisely rectangular shape from southwest to northeast from today's Hundskehle to the slope of the Danube. The medieval part of the monastery took up about half of the Roman camp area. Under Emperor Valentinian (364–375) the mostly wooden buildings of the camp were replaced by stone buildings. The camp had rounded corners and was also surrounded by a double pointed ditch. The fortification of the camp forms a long rectangle with its decumanus (main camp road) to the north-east-south-west on a rock terrace sloping slightly north to the Danube. It thus covered an area of approximately 2.2 hectares. Despite the northern front of the camp, which has not yet been archaeologically proven, Hannsjörg Ubl assumed its width in south-east-north-west direction to be approximately 110 m. The extent of the fort could be determined up to the so-called Hundskehle (street). However, it has not yet been possible to precisely determine its extent for all directions. With almost certain certainty, however, an elongated rectangular floor plan with a size of approx. Assume 2.2 ha.

- North: So far, the course of the north side of the camp has remained unknown, it was probably parallel to the northern monastery wall.

- South: Ubl suspected the southern front of the camp to be on the southwest wall of the monastery cellar, in connection with a wall that had already been investigated by Eduard Nowotny.

- West: The west wall is likely to lie exactly on the edge of the abbey plateau leading to the Kierlingbach, but it is possible that no remains of it have been preserved due to erosion.

- East: According to Ubl, the Roman period wall structures uncovered in the cloister and south of the Sebastiani Chapel had the same orientation as the eastern camp wall. Ubl also deduced from this that the axes of the wood-earth camp and the stone camp I also had a significant impact on the floor plan of the late antique camp.

Due to the modern construction and the associated small-scale excavations, an exact interior layout is still missing today. What is essentially known is the axial alignment of the buildings, which also determined the medieval construction. Only the storage bath (hall and three-chamber system with tub apses) with its several renovation phases is well documented. Barracks were recognized under the cloister and under the Leopoldi Chapel. Small traces of the interior development could also be found in the Sebastianikapelle, but they were severely disturbed by the medieval cemetery. In the east of the area, a corner tower was discovered in 1953/1954, a little west of the former palace building by Leopold VI. In the 19th century a rounded wall was observed a little north of the horseshoe tower, which was uncovered a little later, which could have belonged to one of the gates (porta principalis dextra) of the fort.

Building history

Wood-earth period

In the 1st century a wood and earth fort was built, the exact dimensions of which are not known. The latest dendrochronological studies have shown that this happened as early as the middle of the 1st century. Towers, gates and interior structures such as B. Magazines, barracks and administrative buildings were wooden constructions with walls plastered with clay using truss technology. Isolated findings from the wood-earth store in the late first century indicate two phases of construction. In this second construction phase, it was enlarged somewhat after the retentura (= rear storage area in contrast to praetentura ). The reason for this narrow, elongated camp floor plan could have been a change of troops that took place at the beginning of the 2nd century, namely when the cohors quingenaria was replaced by a cohors milliaria . Decay, fire disasters or hostile attacks repeatedly led to the destruction of the buildings, which had to be renewed or rebuilt several times up to 100 AD.

Stone period I

Around the year 100 AD the new stone fort wall was built (probably by the cohors I Aelia sagittariorum ). From this point on, increased stone building activity can also be observed in the interior, for example the construction of a north-south oriented barracks building with a pillar portico. The barracks were given tiled roofs. The warehouse was also repeatedly rebuilt later. These modernization measures can be dated to the late 2nd and early 3rd centuries according to brick stamp finds. The stone construction period is also characterized by several construction phases of the fortifications and interior structures. Internal fort buildings from the 1st to 4th centuries were discovered in the monastery cloister and have been partially preserved. An oven from the 4th or 5th century has been uncovered nearby. On the eastern flank, the bathhouse could still be identified in the camp area. The rounded southern corner with a corner tower set on the inside was excavated east of Albrechtsgasse, which was later built over with a fan tower. To date, there are still no more detailed clues about the long side of the fort. These dimensions can also be verified for a number of other auxiliary forts. In the vicinity of the burial ground on the Buchberg, another moat (Spitzgraben) was discovered, which probably once surrounded a march or training camp.

Stone period II

In the first half of the 3rd century, based on the distribution of the brick stamps, there was widespread construction activity, and renovation work can be documented in the later 4th century. But this was not the last renovation work in the Klosterneuburg camp. In the last third of the 4th century a cistern was built, the shaft of which was supported with spolia from the burial ground on the Buchberg (1st – 3rd centuries) from the Middle Imperial period. From the same period of time, changes (finding of two milestones reworked into gate walls and an altar as a gate threshold near the camp wall in the east) could also be determined at the eastern camp gate. In order to go around the southeastern horseshoe tower, the moat also had to be dug. The last construction work at the Klosterneuburg fort can be traced back to the findings of bricks from the so-called OFARN group in the late 4th century. Then the facility fell into disrepair. Provisional patchwork in dry construction technology on the wall as well as the erection of dwellings in primitive wood and clay construction inside the camp can be traced back to the 5th century.

Towers

The Klosterneuburg horseshoe tower dates from the 4th century AD and is so far unique in Upper Pannonia. In its construction it is very similar to Noric specimens (see also Zwentendorf , Traismauer , Mautern an der Donau and Zeiselmauer ). In terms of its dimensions, it is comparable to the “Hunger Tower” from Traismauer. In the majority of this type, the width of the wall was wider on the rounded front (basket arch) than on the sides and the rear wall, as in Klosterneuburg. The tower did not protrude completely outward in front of the wall, but also extended somewhat into the interior of the camp. The Klosterneuburg copy shows a very depressed basket arch. This created sharp corner edges on both sides, which should actually be avoided by this construction method. This anomaly is only found in two specimens in Pannonia ( Visegrád , Szentendre ).

In summary, this is an intermediate tower with a U-shaped front, partly built over a demolished rectangular intermediate tower:

- Size 6 × 10.60 m, ratio 1: 1, cantilevered about 7.20 m from the warehouse wall,

- Jump back about two meters,

- Thickness of the wall in the front part 1.40 - 1.60 m, towards the inside of the warehouse about one meter,

- Thickness of the back 1.10 m, on the other sides 1.65 - 1.85 m,

- Internal dimensions 2.70 × 7.70 m.

The foundation height is between 1.20 m and 1.70 m, as the front part of the tower was placed in the older fort moat. Foundation protrusion in the protruding part outside and inside each 0.10 m. The rising masonry (double-shell cast masonry) is made up of cuboid-like rubble stones, mixed with bricks and a little mortar. The fascia walls consist of regularly cut blocks with a length of 0.30 m. Unprocessed rubble stones were used for the cast wall core. At the rear is the 1.10 m wide door opening with a two-part threshold.

Its predecessor, a slightly warped, rectangular intermediate tower, dates to the early 2nd century. Its dimensions are 4.20 × 4.80 m, the ratio between its width and depth is 1: 1.143. The thickness of the front and fort walls was around 0.80 m, that of the remaining tower walls 0.65 m. The foundation is made up of three layers of rubble stones, which were laid irregularly and without mortar. The rising masonry consists of carefully layered rubble stones with grouting. In the south-west corner of the tower, the wall was torn down in late antiquity and a new building was apparently built instead.

Fort bath

Finding

The ancient building was discovered immediately behind the south-eastern fort wall during the excavation campaigns in 1953/1954 on the monastery square in Klosterneuburg. The facility ( balineum ) is oriented to the north-west / south-east and is divided into three heatable rooms (building A), followed by an unheatable hall (building B) in the north-east. Rudolf Egger initially interpreted the building as an early Christian church with a crypt . It had two tub apses, was operated until late antiquity and (like the barracks) was redesigned several times. According to the findings of the brick temple, its last stage of expansion was in the late 4th century.

A widens towards the south-east by approximately one meter, with its south-western outer front being exactly at right angles to the camp wall. This fact could also indicate that the fort's axis system is not entirely at right angles. The facility is likely to have been built as a bathing building. It remained unclear why the lines of the two main walls differ so greatly from one another. So far there are no references to water inflow and outflow facilities either. A slot on the threshold to room III z. B. could not have been the opening for a water pipe, since it has completely smooth walls. In addition, there is no evidence of water pools. If the facility was actually used as a bathhouse, this cannot have lasted long.

Building a

Room I is located in Warmbadetrakt A, which is extended by two apses. This was recognized as a caldarium (warm bath). The praefurnium (boiler room) is located in front of the lateral apse , also because otherwise the space for the passage between the warehouse enclosure and the bathing building would no longer have been sufficient. The adjoining room II is defined as a tepidarium (moderately warm room); it was also heated from room III, whose praefurnium is on the north-west side. This was also the only access to the warm bathing wing. As a passage to the cold bath wing, it should be interpreted as a tepidarium rather than a sudatorium (sweat bath). This also coincides when compared with other bathrooms that organized their bathing process in rows and were equipped with three warm bath rooms (arranged one behind the other). The purpose of the hose heating in room II has not been fully clarified. It may have been installed in the original facility due to functional difficulties. Rudolf Egger suspects the installation only for the duration of the construction work in room II. When the camp was left to the civilian population, building A was probably extended by the apsid hall.

Building B

Building B is separated from building A by clearly recognizable construction joints and must have been added on at a later time. In front of the warm bath wing, however, an unheated area is required, in which the frigidarium (cold bath) and the apodyterium (changing room) were housed. Either this construction joint is justified in the construction process if the hot bathing rooms were built first, or a previous construction for building B is to be assumed. However, there are no clear archaeological traces for this. Building B is, however, clearly assigned to the storage pool. In the apse on the south-east side there was probably a piscina (water basin). Since no room subdivisions were recognizable either, it is to be interpreted as a multi-purpose room, which probably combines the functions of a frigidarium and a lounge. B is disturbed in its northern part by a later cemetery. If there are no more additions here, it should also have served as an apodyterium .

Building material

The walls of A and B are made of quarry stone with mixed bricks, about 0.6 m thick. In the south-western part there were also some larger ashlar stones. In addition, bricks were used for the older flooring of A and the heating openings. This also applies to the 0.45 m wide separating wall between the apse and the nave of Building B.

Construction phases

A total of two construction phases could be determined. In terms of time span, they are not very far apart. The older building A will - judging by the brick stamps found there - be placed in the reign of Emperor Valentinian I or in that of Emperor Theodosius I (379–395). Roof tiles and masonry tiles from the early imperial era were also found, but based on the older mortar residues that were still adhering, these could be clearly identified as being used again. Rudolf Egger suspects a fire disaster as the cause of the end of phase I, as a heavy layer of fire could also be determined.

Phase II is almost identical to Phase I in terms of the type of material and construction. Building A is likely to have been used almost unchanged after its renovation. Only its floors - apart from the one in the east apse and room I - have been raised slightly, which means that the openings between rooms I and II have been filled in. The floor of A was probably made of boards due to a layer of wood ash. However, the round arches of the heating system remained free of the openings that led to the apses. Phase II can probably be dated to the early 5th century; its end was again brought about by fire.

Subsequent smaller additions and conversions mainly affect the warm rooms. The three heating openings from the tepidarium (II) to the caldarium (I) are only framed by tiles. They seem to have been added later, as they were not designed as brick arches - as was the case with the hot air vents in the first construction period. This probably also in connection with the installation of the primitive hose heating duct in room II, the praefurnium of which is in room III. At the latest with the decay of this heating system in the 5th century, the building was no longer used as a bathhouse.

garrison

For Klosterneuburg three units of the auxiliary troops ( auxilia ) could be identified by inscriptions. In addition, the presence of members of the legio X Gemina in the camp can be proven on the basis of large numbers of brick stamps found . This, however, probably not as a guard, but primarily as a building vexillations and brick supplier. In connection with the discussions about the identification of Klosterneuburg as Asturis , attempts are sometimes made to associate the cohors prima Asturum (the first cohort of Asturians) with the fort. The only brick stamps that mention this troop, however, come from the Noric fort Zwentendorf . So far there have been no indications of the presence of this unit in Klosterneuburg.

| Time position | Troop name | comment | |

| 1st century AD |

Cohors prima Montanorum (the first cohort of mountain dwellers) |

This unit is likely to have provided the first occupation force (80-103 AD?) Of the wood-earth fort. Mainly because of the military diploma of the Soio of June 13, 80 from the time of Emperor Titus , which was found behind the choir of the collegiate church and which is also mentioned in the text (see notes). It is also possible that she was assigned to Trajan's Dacian war around 101 AD - in association with the legio XIII Gemina - or was already briefly on the Sarmatian front in 92 in the Danube fort Budapest-Albertfalva .

The cohort could subsequently have been replaced by the legio XIV Gemina Martia victrix, which had stopped the troop transfers to the Vienna area that had become necessary due to the Dacian war. Many different types of brick stamps from this legion were found in Klosterneuburg. However, it has not yet been clarified whether these were only construction or garrison troops. |

|

| early 2nd century AD |

Cohors secunda Batavorum (the second cohort of the Batavians ) |

This cohort has been in the Pannonian provincial army (exercitus pannonicus) since 98 AD (military diploma from February 20, 98) . On the basis of a few fragments of brick stamps with the imprint "II" and "BA" discovered in Klosterneuburg, Hannsjörg Ubl believes that he can prove that this unit has replaced the prima Montanorum . Another military diploma from Mautern an der Donau from the years 127 / 128-138 proves her membership of the Noric provincial army. Ubl assumes on the basis of the brick stamp mentioned above that the Batavians must have appeared in Klosterneuburg before 128 and remained there until the time of Hadrian . | |

| Mid-2nd century to 3rd century |

Cohors prima Aelia Caesariensis milliaria (severiana) sagittariorum equitata (the first mounted Aelian cohort of archers) |

This troop of 1000 horsemen arrived at the Klosterneuburg fort in the middle of the 2nd century AD. It stayed there until the end of the Roman military organization on the Upper Danube. This unity has been proven primarily through inscriptions. The investigation of a section of the moat is important here. Two inscription stones built as spolia could be recovered here, which the tribunes of the 2nd century:

and two inscriptions from the 3rd century AD showing a certain

name as tribune (officers) in Klosterneuburg. In addition, a Tesserarius cohortis (non-commissioned officer) from the 2nd century should also be mentioned in this context . In addition to the inscriptions, a large number of brick stamps of this unit were found, which also appeared in other places on the Danube Limes. Since the honorary name SEVERIANA is also mentioned with some of them, it is considered certain that the unit was still stationed in Klosterneuburg during the reign of Emperor Severus Alexander (208-235). The further fate of this unit cannot be traced beyond the 3rd century. According to H. Ubl, it was probably converted into a cavalry formation under a new name in the course of the late Roman military reforms. |

Equipment of an auxiliary soldier in the 3rd century (figurine in Kastell Saalburg )

|

| 4th to 5th century AD |

|

Due to the sparse sources, only very vague statements can be made about the fort occupation in the late 4th and early 5th centuries. For this question really just a cohort of under would Diocletian and Constantine reorganized border troops, a unit abkommandierter rider and federates the gens Marcomannorum (members of the Germanic tribe of the Marcomanni ), probably by the end of Roman rule in Klosterneuburg kept up guard duty. In the Notitia dignitatum a Tribunus cohortis in Arrianis is mentioned in the list of troops of the Dux Pannoniae Primae et Norici Ripensis . |

Vicus

The vicus or camp village of Klosterneuburg is now completely built over by the upper town. Up to now neither its exact extent nor the larger remains of the building could be determined from this. However, the brick stamps found in this area suggest a similar development to that of the fort. Nothing is known about the development plan and its road and path network to date. It encircled the fort in an arc from east to west and, at least in the east, almost reached the defensive moat. In terms of area, it should have reached the dimensions of the medieval upper town. Possibly he scattered something towards the Buchberg in the south. In its heyday, the population of the Klosterneuburg vicus was by and large enjoyed a modest prosperity, as meager remains from the houses (remains of wall paintings) and imported ceramics suggest.

The number and density of the graves dug in the late 4th and early 5th centuries suggest that the community was still homogeneous and viable during this period. It has not yet been possible to determine whether this was still living in the unpaved vicus or already behind the camp walls. Based on the finds, it can only be seen that the late ancient population of Klosterneuburg was no longer entirely Romanesque , but was also strongly influenced by new immigrants of Germanic origin. These can no longer be proven in the old camp village. They probably all lived in the dilapidated fort itself. Their graves have not yet been discovered. They probably buried their dead directly in the camp area, where, according to old reports, burial places of this type are said to have been found time and again.

population

The grave steles recovered from a cistern in the Kuchlhof between 1982 and 1983 provide information about the composition of the residents of the vicus of Klosterneuburg. Their uniform design and material (Wienerwald or Greifenstein sandstone) also suggest a stonemason workshop that is located here. Their inscriptions and the portraits of the deceased depicted on them show that a distinction was made here between members of the military (regardless of whether they were active or already released) and civilians. Both groups can be easily separated from one another on the basis of their names, since the typical Roman first and last names are missing for the villagers who are descended from indigenous (native) tribes.

Two of these inscription stones also allow an insight into two families of the Klosterneuburg vicus . On the stele of Ulpius Avitus z. B. the deceased is shown together with his family. Next to the head of the family, a veteran of the cohors I Aelia Sagittarorium , who is depicted with his military coat (sagum) , his wife stands in local costume, between her three children, a boy and two girls, on the far left a young woman, probably the only survivor who later also had the tombstone made. Their names are also given. The parents, above all the father Ulpius Avitus, 75 years old, the mother Victorina, 40 years, the brother emeritus, eight years, his sisters Avita, ten years, and Superia, eight years. They were all buried on behalf of the eldest daughter Victoria (whose age is not specified).

The second inscription stone from another veteran family is believed to have been erected 50–70 years later. However, no small children are mentioned on it. It should be dated to the early 3rd century. The persons named on it (the mother Crescentina, 50 years, and her two sons Karinus and Crescens) all have the same family name, Septimius and Septimia. The memorial stone was probably donated a long time after their death, perhaps because the client Septimius Karus, the brother of the two deceased, first had to raise the necessary amount of money. The grave was also intended for his wife Victorina, his father Genialis and for the two sisters Quaetilla and Presentina.

Burial grounds

The grave fields were at the foot of the Buchberg, right next to the arterial roads and thus corresponded to Roman legislation, which ordered that the graves were to be placed outside the built-up area. At the burial place, there does not seem to have been any clearly recognizable separation between military and civilians. The first cremation burials were laid out directly on the Limesstraße (now roughly the Buchbergasse – Babenbergergasse line) which extends on the slope of the Buchberg into the Kierlingtal. In antiquity, the cul-de-sac to the camp gate also ran here. The area between Raphael-Donner-Gasse and the grammar school was likely to have been the center of the early imperial burial ground. The tombstones of the Kuchlhof (see above) must also come from here. The expansion to the west has not yet been recorded. However, a horizontal stratigraphy from west to east can be determined. During the systematic excavations of 1983/84, attention was drawn to these cremation burials from the imperial era, but they were sometimes overlapped by graves from late antiquity. Horse burials were also documented several times. From the late 3rd century onwards, the dead in Klosterneuburg were buried unburned in simple grave pits, brick or stone boxes with their grave goods. In the south-east of the fort, sloping from the Buchberg, was a late antique burial ground, the south-east border of which is to be found in the area of the Protestant rectory. In late antiquity, graves were probably also laid inside the camp itself.

Limes course between Fort Klosterneuburg and legion camp Vindobona

| ON / name | Description / condition | Illustration |

|---|---|---|

| Watchtower / Burgus Vienna-Oberdöbling and Nussdorf | Oberdöbling is located in the urban area of the federal capital Vienna and is part of the 19th district of Vienna. In 1872, Roman walls were discovered in a garden at Döblinger Hauptstrasse 90, near the slope to Heiligenstädter Strasse 69. When fruit trees were moved, the remains of this wall were found again in the same year. Accompanying finds were Roman bricks, a hollow brick and three building bricks with the stamp "TEMP (ore) UR (sicini)" and a brick from the Legio XIIII. Various coin finds in Döbling consisted of a sesterce by Antoninus Pius and two denarii from the time of Marcus Antonius and Augustus . In 1907 P. Zeiler discovered a hoard of 1100 late Roman copper coins at the vault of the Krottenbach.

The ancient wall remnants stretching from west to east and south was identified as part of a late Roman watchtower / Burgus . It consisted of rubble stones, was 1.26 m thick and still preserved up to a height of 1.1 m. The west-eastern part was still 3.6 m long, the southern 2.7 m. Both were connected by a slightly rounded corner. It was constructed very massive and could only be removed by blowing it up with black powder. Due to the brick temple of dux Ursicinus it is believed that the watchtower at the time of Valentinian I. was built. Ursicinus was the commander of the Noric and Upper Pannonian border troops under Valentinian and supervised the last Roman construction work on this section of the Limes. Another tower site is suspected to be near the castle stable in Nussdorf. The tower was probably used to monitor the Danube floodplains and to transmit signals on the Limes. From his position one had u. a. also a good view to Deutsch Altenburg or Hainburg / Thebnerkogel and Vienna. |

|

| Vindobona legionary camp |

Monument protection and remains

No remains of the fort are visible on the monastery plateau itself. In 1954 the remains of the wall of the camp bath were stabilized, but then filled in again. Only a small excavation cut in the north of the cloister was preserved in 1997. It shows wall sections from the 1st to the 14th century. A few years ago , the foundations of the Capella Speciosa in Babenberg were exposed on Stiftsplatz and converted into a small exhibition area. A Roman cistern in the Kuchlhof was not filled in, but covered. A Roman inscription stone is in the Protestant rectory, the other in a house on Agnesstrasse. Roman finds and inscriptions can be viewed in the abbey lapidarium by prior arrangement, other finds - especially those from the vicus - are kept in the city museum and can only be viewed by prior arrangement.

The facilities are ground monuments within the meaning of the Austrian Monument Protection Act . Investigations and targeted collection of finds without the approval of the Federal Monuments Office are a criminal offense. Accidental finds of archaeological objects (ceramics, metal, bones, etc.) as well as all measures affecting the soil must be reported to the Federal Monuments Office (Department for Ground Monuments).

See also

literature

- Alfred Schmeller: The excavations in Klosterneuburg. In: Hermann Fillitz (Red.): Contributions to art history and archeology of the early Middle Ages. Files for the VII. International Congress for Early Medieval Research, September 21-28, 1958. Böhlau, Graz a. a. 1962, pp. 291–324 (note: the southern U-tower is still referred to here as the "Flachabsidenbau").

- Rudolf Egger : The facility in the northwest of the Capella Speziosa. In: Hermann Fillitz (Red.): Contributions to art history and archeology of the early Middle Ages. Files for the VII. International Congress for Early Medieval Research, September 21-28, 1958. Böhlau, Graz a. a. 1962, pp. 325-326.

- Herwig Friesinger , Fritz Krinzinger : The Roman Limes in Austria. Guide to the archaeological monuments. Publishing house of the Austrian Academy of Sciences, Vienna 1997, ISBN 3-7001-2618-2 , pp. 236-240.

- Kurt Genser: The development of the Roman Limes on the Danube in Austria , Salzburg 1975, pp. 74–84.

- Kurt Genser: The Austrian Limes in Roman times. A research report (unpublished dissertation) Salzburg 1982, Part II, pp. 1113–1203.

- Kurt Genser: The Austrian Danube Limes in Roman times. A research report (= The Roman Limes in Austria 33). Publishing house of the Austrian Academy of Sciences, Vienna 1986, ISBN 3-7001-0783-8 , pp. 402-423.

- Hannsjörg Ubl : News about the Roman and Babenbergic Klosterneuburg. In: Yearbook Klosterneuburg Monastery NF 11, 1979, pp. 99–125.

- Manfred Kandler , Hermann Vetters (ed.): The Roman Limes in Austria. Vienna 1989, pp. 166-173.

- Wolfgang Pietsch: A typology of the camp and fort towers on the Noric and Pannonian Limes , unpublished diploma thesis, Vienna 1993, p. 180.

- Hannsjörg Ubl: The Roman Klosterneuburg. In: Floridus Röhrig, Gustav Otruba , Michael Duscher u. a .: Klosterneuburg. History and culture. Volume 1. Klosterneuburg / Vienna 1992, pp. 39–120.

- Gudrun Wlach: Roman bathing facilities in Austria (unpublished dissertation, Vienna 1986), pp. 158–164.

- Austrian Federal Monuments Office: Find reports from Austria. Volumes from 1958 to 2003,

- Reinhard Pohanka: The Roman Vienna (= History of Vienna Volume 1). Pichler Verlag, Vienna 1997, ISBN 3-85058-145-4 .

- Roman Igl: Klosterneuburg. Auxiliary fort - vicus . In: Verena Gassner / Andreas Pülz (ed.): The Roman Limes in Austria. Guide to the archaeological monuments , Publishing House of the Austrian Academy of Sciences, Vienna 2015, ISBN 978-3-7001-7787-6 , pp. 239–241.

Web links

- Location of the fort on Vici.org

- Location of the St. Jakob-Heiligenstadt tower, Vienna on Vici.org

- Location of the tower in Oberdöbling, Vienna on Vici.org

- The Roman Limes in Austria

- City Museum Klosterneuburg

- Klosterneuburg Abbey

- Trailer "The Roman Limes in Tullnerfeld" on YouTube

- Austrian City Atlas History of the City of Klosterneuburg

Remarks

- ↑ Kurt Genser: The Austrian Danube Limes in Roman times. A research report. Vienna 1986, p. 407 ff.

- ^ Herbert Franz Weinzierl: Post-antique settlement development on the Roman Limes in Austria. Vienna 2018

- ^ Karl Holubar: Roman camp Arrianis. The Limes in Klosterneuburg. Klosterneuburg 2018

- ^ Tabula Peutingeriana, segment V.

- ↑ See also Kurt Genser: Der Römische Limes in Österreich , 1986, pp. 408–412.

- ↑ CIL 3, 5645 , CIL 3, 5646 , CIL 3, 5647 .

- ↑ [ OF ] ficinia [ A ] uxiliares [ R ] ipenses [ N ] orica = "Administration of the Noric border troops".

- ↑ CIL 3, 4660 .

- ↑ Zsolt Mráv: Archaeological research 2000–2001 in the area of the late Roman fortress of Göd-Bócsaújtelep (preliminary report) 2002. In: Communicationes archeologicae Hungariae 2003. Népművelési Propaganda Iroda. Budapest 2003. p. 105.

- ↑ Ádám Szabó , Endre Tóth (ed.): Bölcske. Roman inscriptions and finds - In memoriam Sándor Soproni (1926–1995) Libelli archaeologici Ser. Nov. No. II. Hungarian National Museum, Budapest 2003, ISBN 963-9046-83-3 , p. 80.

- ↑ CIL 3, 5646 .

- ↑ CIL 3, 5649 .

- ↑ CIL 16, 26 = CIL III p. 854; Diploma XI = p.1960, DXIII.

- ^ Neuburger-Mathilde Grünewald 1974, p. 22.

- ↑ Hannsjörg Ubl: Find reports from Austria 18, 1979, pp. 497-500.

-

^ Translation after Ekkehard Weber , in: Vindobona - the Romans in the Vienna area. Catalog for the 52nd special exhibition of the Historical Museum of the City of Vienna, December 8, 1977 to April 9, 1978, Vienna 1977, p. 251 f. Imperator Titus Caesar Vespasianus Augustus, son of the deified Vespasianus , high priest, to the IX. Times owner of the tribunician power, for the XV. For the time being proclaimed emperor, father of the fatherland, censor , consul for the eighth time, has named those horsemen and infantrymen who are in the IIII Alen and XIII cohorts:

Alen

I Arvacorum,

I Civium Romanorum,

II Arvacorum,

(II) Frontoniana and

Cohorts

I Alpinorum,

I Montanorum,

I Noricorum,

I Lepidiana,

I Augusta Ituraeorum,

I Lucensium,

I Alpinorum,

I Britannica,

II Asturum et Callaecorum,

II Hispanorum,

III Thracum,

V Breucorum,

VIII Raetorum,

those in Pannonia under the (High Command des) T (itus) Atilius Rufus are stationed insofar as they have received the honorable discharge after XXV and more years of service, and (also) those who were in the Alen I Civium Romanorum and II Arvacorum and in the Cohors VIII Raetorum under the same Commander XXV years, bestowed: the (Roman) civil rights to them personally, their children and their descendants and the right to enter into a valid marriage with the women they were granted at the time of the civil rights ng have already had by granting them citizenship, or, if they were still single, only one with those women who will later take them. (Given) on XIII. June of the year of the consuls L (ucius) Lamia Plautius Aelianus and C (aius) Marius Marcellus Octavius Publius Cluvius Rufus (80 AD).

For the released infantryman Soio, son of Muscellus from the (Thracian) tribe of the Besser, who served in the Cohors I Montanorum, who commands Sex (tus) Nerianus Clemens, the Sex (tus) son, from the Tribus Clustumina.

Checked copy according to the bronze plaque that is placed on the Capitol in Rome on the wall behind the temple of the goddess Fides of the Roman people. Name and seal of the witnesses:

L (ucius) Pullius Speratus,

P (ublius) Atinius Rufus,

C (aius) Pompeius Eutrapelus,

C (aius) Claudius Sementivus,

P (ublius) Manlius Laurus,

M (arcus) Stlaccius Philetus,

L ( ucius) Pullius Januarius. - ↑ Hannsjörg Ubl: Fund reports from Austria 15, 1976, p. 266, Ubl 1979, p. 100 ff. Pro Austra Romana 27, 1977, p. 26 f.

- ^ Johannes-Wolfgang Neugebauer , Christine Maresch-Neugebauer: Find reports from Austria 24/25, 1985/86, pp. 291-292.

- ↑ Hannsjörg Ubl: Find reports from Austria 34, 1995, p. 21.

- ^ Christiane and Johannes Wolfgang Neugebauer / Hannsjörg Ubl: Find reports from Austria 37, 1998, pp. 22-25.

- ^ Johannes Wolfgang Neugebauer: Find reports from Austria , 2000, p. 19.

- ↑ Herta Ladenbauer-Orel: A settlement from the Urnfield period in Klosterneuburg Monastery., In: Jb. Kl. NF 2, 1962, p. 159 ff.

- ↑ H. Ubl: I. The Roman Lapidarium , Klosterneuburg 1993, p. 13.

- ↑ HJ Ubl: News about the Roman and Babenbergic Klosterneuburg, in: Jb. Kl. NF 11, 1979, p. 99 ff.

- ↑ Wolfgang Pietsch: A typology of the storage and fort towers on the Noric and Pannonian Limes. Dissertation, Vienna 1993, p. 77.

- ↑ CIL 16, 26 .

- ^ Krisztina Szirmai: Auxiliary fort and vicus in Albertfalva. In: Paula Zsidi : Research in Aquincum, 1969–2002. In honor of Klára Póczy. Budapesti Történeti Múzeum 2003, ISBN 963-9340-23-5 , p. 93.

- ↑ UBI ERAT LUPA Monument 8085

- ↑ CIL 3, 5647 .

- ↑ UBI ERAT LUPA Monument 4802

- ^ Notitia dignitatum Occ. XXXIV / XVI.

- ^ Notitia dignitatum Occ. XXXIV / XXIV.

- ↑ AE 1992, 1442 ; Illustrations .

- ↑ AE 1992, 1443 ; Illustration .

- ↑ Reinhard Pohanka: 1997, pp. 70-71.

- ↑ Kurt Genser: The Austrian Danube Limes in Roman times. A research report. Vienna 1986, pp. 431-434.