Favianis Castle

| Mautern Castle | |

|---|---|

| Alternative name |

a) Favianis , b) Fafianae |

| limes | Limes Noricus |

| section | Route 1 |

| Dating (occupancy) | Flavian, until 5th century AD |

| Type | Infantry and Alen camp ( Auxilia ), naval station |

| unit |

a) Legio X Gemina pia fidelis (?), b) Legio XIIII Gemina Martia victrix (?), c) Cohors I Ubiorum (?), d) Cohors I Aelia Brittonum (Antoniana) (?) e) Cohors II Batavorum , f ) Legio I Noricorum ( liburnari ) |

| size | 3.6 - 5.25 ha |

| Construction |

a) wood-earth fort (multi-phase), b) stone fort (multi- phase) |

| State of preservation | Square system with truncated corners, western wall integrated into the medieval fortifications, northwestern horseshoe tower completely preserved up to the 1st floor, basement of an eastern horseshoe tower preserved, southwestern fan tower still partly. preserved, part of the south wall visible in the Margaretenkapelle, a late antique burgus or a remnant fort is suspected under the Nikolaihof |

| place | Mautern on the Danube |

| Geographical location | 48 ° 23 '37.5 " N , 15 ° 34' 39.5" E |

| Previous | Limes towers in the Wachau (west) |

| Subsequently | Burgus Hollenburg (east) |

The Favianis fort was part of the security systems of the Roman Danube Limes . It is located in the municipality Mautern an der Donau in Austria , federal state Lower Austria , district Krems-Land .

The fort probably served first as a cavalry camp , in late antiquity also as a base for the Danube fleet ( Classis Pannonica ) and was probably continuously occupied by Roman troops from the 1st to the 5th century. It became particularly important in the 5th century through the political and social activities of Severin von Noricum . In this context it protected u. a. the Severinskloster and in 488 - after the defeat of the Rugier Empire north of the Danube by King Odoacer - was a gathering point for the evacuation of the Romanesque population of Ufernoricum to Italy.

The camp mentioned for the first time in the Notitia Dignitatum , but probably already existing since the early imperial period , could be clearly proven archaeologically . Today the fort is almost completely built over by the old town of Mautern, but its outlines can still be seen in the street grid. Significant remnants of the late antique fort (see Stone Period II) have been preserved above all on the western section of the medieval fortifications and in the Margaret's Chapel. It is one of the best-researched Roman sites in Austria.

Surname

The origin and meaning of the ancient fort name has not yet been clarified with any certainty. Gerhard Rasch derives the fort name from a personal name such as B. Favius , Faventius or Favonis . Possibly he is also on the - cf. also Comagena ( Tulln ) - the garrison unit first stationed here. In this case, it could have been a cohors Faviana (or Fabiana ), who was probably named after its first commander. As was often the case at the time, the name of the fort was also transferred to the neighboring civilian settlement and lasted until late antiquity ( castra Faviana or Fabiana ). The ancient name of the fort can also be found in the Notitia Dignitatum , in the section of the Noric Dux (Favianae) . After the end of Roman rule, the place is mentioned for the first time (around 899) in the Fulda annals as Civitas Mutarensis (the settlement of the toll collectors).

location

At the eastern edge of the breakthrough valley of the Wachau the Danube flows into a wide basin that a swampy in antiquity nor Aulandschaft was with numerous tributaries, the stream has repeatedly changed its course. The fort stood on a tertiary gravel terrace and, according to the sediment findings, was apparently hit several times by major flood disasters. Today, its remains are almost entirely under the old town of Mautern, but some parts of the masonry still remain. The vicus spread around the camp in the south, east and west and covered an area of around 22 hectares, which was a multiple of the fort area. Several grave fields were found in the east and south-east, and there are also isolated ancient burials on the road to Mauternbach.

Road links

At Favianis u. a. The inland Norse iron and salt trade routes are connected to the Amber Road, which runs along the eastern edge of the Weinviertel , to routes that cross the Kamptal into the Elbe - Moldau area and to trade routes that lead further north. However, the fort was not directly on the Limesstrasse. Due to the swampy and impassable terrain between Melk (Namare?) And Mautern, it did not run alongside the Danube bank, but a few kilometers further south. In order to still be able to reach the chain of watchtowers on the Danube without any problems, year-round accesses were created from the Limes Road through small valleys leading to the river. West of Favianis , the endpoints of two of these paths were secured by watchtowers at Bacharnsdorf and Rossatz-Windstallgraben. Remains of such roads (with very pronounced ruts) can still be seen today southwest of Mauternbach and in the Kupfertal south of Bacharnsdorf. There, in the NW-oriented cut of the Dürrenbach, the Geleisestraße led over the ridge of the Dunkelsteiner Forest towards St. Pölten / Aelium Cetium . From here it went east to the next larger camp Augustianis ( Traismauer ) and south to Aelium Cetium .

function

Like the forts in Linz , Enns and Klosterneuburg , Favianis stood on a crossing over the Danube that was important for long-distance trade. Crossing down the Danube was almost impossible due to numerous tributaries and marshy meadows. Upstream of the Danube, the steep and impassable slopes of the Wachau blocked access to the river bank. The primary task of the fort crew was to control this - also strategically important - transition point. It also monitored the connection between the Upper Austrian and the basin landscapes around Vienna.

topography

During the construction of the water pipeline in Kremser Strasse, valuable knowledge could also be gained about the nature of the terrain at the time of antiquity. Accordingly, the river sand sedimentation , which could no longer be reached, especially in the north, was not assumed to be the ancient level , but the upper edge of a loamy sand layer. At the edge of the terrace, the differences between the modern and ancient levels are still minimal. To the north of this ridge, however, over the centuries it was continuously piled up, especially in the Middle Ages and in modern times, the natural low terrace is still clearly visible on the edge of the terrain in the area of the north wall.

In the middle imperial period, on the other hand, the walking level in the northern part of the annex was hardly higher than in late antiquity. At the intersection of Kremser Strasse and St. Pöltner Strasse, a 15 m long terrace was also found. The foundation of the northern fort wall is almost a meter deeper than the fortifications in the south, from here the terrain also drops noticeably. South of the wall, the gradient is one meter over 35 m in length, but to the north it is already 3 m over 35 m in length. The northern wall was therefore deliberately built close to this striking edge of the terrain. The lowest point north of the fort wall is four meters.

In summary, the investigated area is divided into a low terrace up to the edge of the terrain, a small slope (drop around four meters over a length of 60 m) and a smaller knoll that is around one meter higher than the lowest point on the terrain. These prerequisites were probably decisive for the fort being built here. After a dry season in the 2nd and 3rd century, Johann Offenberger assumes a marked rise in the groundwater level. This was probably due to a general deterioration in the climate, which led to widespread floods more and more often and forced the Romans to abandon settlement areas and fortifications near the shore or lower down.

vegetation

Macological studies from the period of stone fort I proved the existence of a deciduous and mixed forest with scrubland and dry biotopes in the vicinity of the fort. At that time there were still numerous oxbow lakes along the main river of the Danube, which were connected to the forest areas of the hinterland. A typical alluvial forest probably no longer existed in the 2nd century. The types of wood found in the fort such as oak, fir, beech and hornbeam confirm this assumption. The main use of these tree species for building houses often led to a permanent change in the natural forest in the vicinity of the Limes fort. In addition, there were references to the cultivation of grain and pulses, the keeping of farm animals, and hunting and fishing.

Hardly any changes can be perceived in late antiquity; deciduous and mixed forest continued to prevail, alternating with scrubland, standing water with reeds and lawn biotopes. There was no contiguous riparian forest belt. Charcoal samples from the buildings inside the warehouse come from hardwood and coniferous trees, and oak and fir could be identified. An extension of the agricultural land around the fort can also be ruled out for this period.

development

The region around Favianis belonged from the 2nd century BC to BC to the Celtic Regnum Noricum , after its incorporation into the Roman Empire , the province of Noricum was founded in the course of the administrative reorganization under Emperor Claudius . Favianis is one of the oldest forts on the Danube Limes, but clear archaeological evidence of the construction of a standard wood-earth fort in the time of the Flavians has not yet been found.

In the period between the first and middle decades of the 2nd century, it was converted into a stone fort, perhaps by members of the two Upper Pannonian legions and the cohors I Aelia Brittonum (stone fort I). Probably badly damaged in the Marcomann Wars, the system then underwent some renovations. Nothing is known about the events surrounding the fort in the 3rd century. It is only certain that the buildings burned down again and the ruins of the fort were not used or rebuilt for a long period of time. The series of coins from the fort and the camp village also shows a noticeable decline in the currency in circulation, which also speaks for a temporary desertification.

The revitalization of the fort square probably took place during the reign of Diocletian , who extensively reformed the border security system. Favianis must have been an important center of Roman presence at this time, since from this time a second Noric legion, the legio I Noricorum (or at least one of its vexillations ) and naval soldiers (liburnari) has been established there. The Danube was previously monitored in this section by patrol ships of the legio II Italica from Lauriacum . As is common in the Danube Limes, the fortifications were massively reinforced and modernized at the beginning of the 4th century, and a patrol boat flotilla was also stationed here (Stone Fort II).

The end of the fort and vicus is handed down in the Vita Sancti Severini , the place is referred to in this chronicle as civitas or oppidum , so it had apparently completely lost its original military importance as a border fortress of the Noric Limes in the late 5th century. Only a small crew under the command of a tribune was available to protect the settlement and its population. This troop had probably already withdrawn to a small remnant fort ( burgus ), which was probably in the area of the Nikolaihof . When the food supply was interrupted, the population called for help, Severin founded a monastery in Favianis and stayed here permanently. This is also because the residence of the Germanic Rugier people was on the other bank of the Danube. At that time, their area of influence probably extended to Lauriacum / Enns. It was very important for Severin's work to stay in constant contact with the real rulers of this region.

On January 8, 482 Severin died in Favianis , a short time later the Rugier king Frederuch plundered the monastery completely. After the defeat of the Rugier Empire by the Ostrogoths, a large part of the Romanes was evacuated to Italy around 488 on the orders of Odoacer . They had supported the Rugians against the Ostrogoths, and their resettlement was intended to prevent the resurgence of Rugian rule. In the final phase of Roman rule, the oppidum became a collection camp and withdrawal point for part of the Romanesque population of the upper and middle Danube. They also took Severin's body with them. The Severinsvita can be seen that many of the novels were difficult to persuade to leave their original homeland despite great stress and constant threat from the barbarian tribes. The majority of the rural population and certainly many city dwellers did not leave their homes. With the emigration of the ruling class, however, the country was finally surrendered to the Germanic immigrants.

The news about the fort ends with the traditions from the Vita . After 488, Favianis is likely to have been largely uninhabited for over 300 years, the findings show no settlement continuity. Due to the presence of a so-called "black layer" (humus), it is assumed that the buildings quickly fell into disrepair and were completely overgrown by vegetation over time. The cultivation of cereals on a smaller scale cannot, however, be ruled out. It is also possible that the area was later used as a cattle pen, which would explain the accumulation of phytolites in the soil.

Research history

After finds from the early imperial era had often come to light, in 1824 a soldier's grave stone, a Roman wall running from west to east was encountered during sewer work in 1892 in Kremser Strasse, an ancient sequence of layers could not be documented until 1996 during the excavations in Melkerstrasse. In 1874, Adalbert Dungel created a large collection of finds from the vicinity of Mautern for the first time. Lambert Karner later carried out some archaeological investigations in Mautern (1890 and 91). Up to the turn of the century Max Nistler and Johann Oehler worked on finds and research results about the fort. After 1903 it was mainly citizens from Krems an der Donau who were in charge of research. Rudolph Weißhäupl took on the administration and cataloging of the found objects, Josef Novotny created a find map of Mautern. In the 1920s some smaller excavations were carried out, between 1930 and 1939 mainly graves and a villa rustica were uncovered. Since the end of the Second World War, the site has been mainly looked after by the Austrian Archaeological Institute (ÖAI) and the Austrian Federal Monuments Office, which have gained numerous important findings about the extent and structural details of the fort over the past 60 years.

Fort

The fort was built in the 1st century as a wood-earth warehouse, where, according to new investigations, at least two construction periods could be distinguished. Massive findings of destruction with remains of rod plaster walls in the area of the rectory garden (south of the castle) suggest that it is located in the northwestern part of what will later be the stone warehouse I. The associated camp village probably developed first to the west and south of the fort, as traces of timber frame constructions (remains of screed, cellar, pits, wicker walls with clay plaster) could also be observed here. Due to the reconstruction of the middle imperial north gate and the findings at the south gate, however, it is unlikely that the north gate - as is usual with the Norican forts - will be regarded as the main gate. Rather, the main axis of the camp seems to have run in a west-east direction - which also coincides with the Limes Road. The principia (staff building) of the camp is likely to have been in the northern sector of the area (see also the floor plan of the Weissenburg Castle ).

In the 2nd century, it was converted into stone warehouse I. Only a few of the building remains that can be clearly assigned to this warehouse have so far been identified. This was probably a classic, rectangular system with rounded corners (playing card shape), four gates and rectangular intermediate towers attached to the inside.

In the 4th century, major structural changes were undertaken to meet the new military requirements and technical innovations at the fort. These adaptations can be seen above all in the addition of U-shaped intermediate towers (horseshoe tower), the considerable reinforcement of the fort wall itself, its rounded corners and the fan-shaped protruding, bastion-like corner towers (fan tower).

The first more detailed investigations were mainly carried out on the still visible remains of the late antique camp. These were mainly the fan tower in the rectory, the north-western horseshoe tower and the western city wall. In 2005 another horseshoe tower was discovered on the north wall, and in 2007 also on the southern part of the west wall. During the excavations it soon became apparent that there was a very complex building history here, which probably ended with a burgus or remnant fort in the area of the Nikolaihof.

A close examination of the southwestern fan-shaped tower revealed that the fort wall had first been removed at the point where it collided with the fan-shaped tower, but was then added to the tower again. Obviously, the northern fence around Steinkastell I, which was closest to the Danube, had not been removed, but rather left as a kind of refuge (or perhaps as additional flood protection) for the civilian population in the area. The relocation of the late antique fort to the south and the location of the oppidum that later emerged within its walls (the civitas of Eugippius) can still be seen clearly in the aerial view of the medieval and modern city. Subsequently, there is also a dense development of the city south of the line Nikolaihof - western fan tower, while the northern part of the fort site was largely fallow, as it remained in the possession of the Catholic Church.

The northern front of the fort facing the bank of the Danube runs in front of today's Roman Hall and under the northern wall of the city palace. From there it stretches to the east and turns under the northern front of the Nikolaihof to its east side. The fortifications in the north, especially the northwest corner, were repeatedly damaged by floods or ice jams due to their proximity to the Danube. The location of the eastern wall of stone fort II with its ditch in front of it is z. B. can still be seen in the garden of the Nikolaihof, based on a bump running from north to south.

The south wall can be recognized particularly well by the Margaretenkapelle (Frauenhofgasse), which stands parallel to the fort's former moat. However, the exact course of the south wall is not certain. It is not known with certainty whether it remained and whether the fort was reduced in size in the course of the redesign in late antiquity (stone fort II) or whether the southern fortification - including an ancient wall under today's Margaret Church - was completely redesigned and built.

Construction phases

The four most important construction phases for the fort's fortifications could be distinguished:

- double pointed ditch system tangible, with which the western extension of the presumed first wood-earth fort could be proven,

- Enlargement of the wood-earth warehouse to the west, erection of a larger timber frame building (stables), here too the western boundary could also be precisely determined,

- another shift of the area to the west and the erection of the first stone camp wall (stone period I) and

- in the case of a rectangular inner tower, its replacement by a late antique horseshoe tower (U-tower) has been proven (stone period II). It is believed that these U-towers were erected at the same time as the fan-shaped towers at the corners of the camp.

After interpreting the findings from 2007, the excavators came to the following results:

- Wood-earth fort (construction periods 1–2): for this complex, its double moat system has now also been recognized on the west side of the fort. The findings recognized as an early ditch during the investigations in the parsonage in 1954 and the reinterpretation of a garbage ditch as part of an early pointed ditch suggest that the western ditch system still protruded beyond the northern, mid-imperial, boundary. The moat, discovered in 2006 near today's Roman Hall, is also assigned to construction period 1, which would result in an expansion of the wood-earth fort beyond the northern boundary of the late antique fort.

- Stone fort I (construction periods 3–5): the V-shaped double ditch of this period was detected for the first time, as well as stable buildings, which speak for the presence of a mounted unit. In addition, an expansion of the fort area to the south (also for the western boundary of the fort) was determined. The displacement of the barracks building by one room width and the construction of the fort wall directly at the inner edge of the filled trench from construction period 2 also prove the further enlargement of the fort area. The course of the wall was also traced in 1966 in the Missongasse excavation, where a trench was cut. Contrary to previous assumptions, the western fort wall runs a little further west, in the south-western area of the fort directly on the eastern row of houses on Missongasse. The discovery of an inner tower would be complemented by the uncertain assignment of another, similar finding, which lies under the northwestern fan tower, which came to light in 1972/73 in the rectory under the neck of the fan tower there. The wall, which turned at right angles, was only recognized later as a possible corner of the fort.

- Stone fort II (construction periods 6–7): In addition to the redesign of the barracks, the excavators note uncertainties in the dating of the fort wall, which could have been rebuilt in construction period 4 as well. Compared to the interpretations of Stefan Groh from 1996, the excavators on the site of the vinegar factory do not see any hiatus in the settlement history of the second half of the 3rd century. The construction of the U-Tower could have taken place as early as the end of the 3rd century. No expansion is being considered, only a reduction in size by moving the late antique fort to the north.

Wood-earth period

Archaeological evidence of wood-and-earth forts can generally only be found very rarely on the Danube Limes. The exact location and size of the early Roman fortifications of Mautern are also still unclear. The time period of the Flavian emperors, around 70/80 AD, is most likely to be considered for its establishment. This assumption is supported above all by finds of Arretine-Padan sigillata and coin finds. The findings show that after the surrounding forest had burned down, simple timber frame structures were first erected and then pointed trenches were built.

In the years 100/110 AD, the fortification trenches in the south and west were leveled again to expand the area of the fort. However, the total area of the first camp cannot be precisely determined from an archaeological point of view, as the sections of the later Middle Imperial building no longer contain any finds from the 1st century. The exact construction of the first fortifications is also unclear. Due to the location of the layer of destruction and the finds from the vicus, the early wood-earth fort is believed to be on the area of today's parish garden and the square south of the castle.

However, the lower terrace on the Danube also seems to have been the natural boundary to the north for the early wood-earth fort. If one summarizes the previous findings, the result for the early fort complex is a hypothetical north-south extension of 110 m in length; its eastern boundary is believed to have been found in a trench of stone fort I cut in 1871 on Rathausplatz / corner Nikolaigasse, the length of the west-east axis is therefore assumed to be 160 m. The wood and earth fort thus covered an area of approximately 1.76 hectares. In general, however, the size of the Noric Limes fort cannot be precisely clarified according to the current state of research except for the Zwentendorf fort . The size of the fort made it possible to accommodate a 500-man cohort (cohors quinquenaria) , less a cohort of 1,000 (cohors millaria) , although the size of such a facility means that only limited conclusions can be drawn about the occupation.

In the Trajanic-Hadrianic period, the camp was likely to have been expanded somewhat towards the south. The civil vicus gradually formed around the fort in the south and west - later also in the east . The area was rebuilt with timber frame buildings - almost the same in their dimensions - a procedure that was by no means unusual for Traian forts on the Noric-Pannonian Limes. The evaluation of flotation samples from this time shows that the alluvial forests were completely cleared, wet meadows drained and bushy areas converted into fields. These massive interventions in the ecological environment of the fort can only be related to the large-scale construction measures in the course of the expansion of the fort (and probably also the vicus). Only the fortifications on the south side could be partially reconstructed. This could have looked like this. When the trench was excavated, a wall was first piled up (location: row of houses north, Frauenhofgasse), which was clad with a double mud brick wall and a wooden battlement. The remains of mud bricks were found in the backfill of the pointed trenches.

Based on the sediment analyzes from the excavations in Frauenhofgasse and the water supply cave , the following scenario for the end of the wood-earth fort could be reconstructed: As already mentioned, the camp was built on a terrace protected from flooding. The determination of the fluvial sand layers showed that this took place in a climatically warmer time period. However, as the weir ditches were deepened into the groundwater area as well as recurring flood events and water ingress, they silted up over time and were obviously no longer cleaned or dug afterwards.

It is difficult to determine how long this final backfill took place; it could have happened very quickly. However, since the filling material of the trenches also contained a large amount of mud brick or hut clay fragments, it is very likely that the early fort was razed as planned, as these artefacts can only come from the interior of the fort and the vallum . Finds of bones or ceramics are almost completely missing, which also speaks in favor of the destruction of the early fort ordered by the authorities, since a long-lasting loss of importance in Roman pointed trenches is usually reflected in the form of secondary use as a landfill. The fort area itself retained its original function.

Trench system

After evaluating the findings recorded in 1954 and 1996, an approximately 32 m wide fortification system with three trenches was identified. The average width of Roman trenches was between 2.5 and 6 m, their depth between 1.2 and 2.7 m. The width of the trench zone was determined according to the throwing distance of the spears and can be set at 15-25 m. It therefore often happened that the foremost trench was only dug at a distance of 6 m from the fortification wall.

The Spitzgraben, discovered in 1954 in Frauenhofgasse, ran in a west-east direction, had a slope angle of 38 degrees and could be followed over a width of eight meters. It could once have been part of the northern moat system of the early wood-earth fort. Herma Stiglitz and Christine Ertel assigned this trench to Stone Fort I. However, according to the latest research results, this thesis is no longer tenable, as the southern defenses of stone fort I could be clearly demonstrated in the excavations at Frauenhofgasse and Melkerstrasse in 1996 (barracks barracks).

A defense system consisting of at least three trenches was attached to the wall, one of the two larger ones having a cleaning trench sunk into the bottom. The width of the two larger trenches of the Südwall is comparable to other trench systems on the Danube Limes. Its great depth of 7.8 to 8 m and the absence of walls lined with clay suggest that the groundwater level was low when the fort was built. Furthermore, no indications of obstacles to approach (pitfalls, lilies, etc.) were found.

On the other hand, hardly any findings are available for the north, west and east sides. In the north, the oldest structural remains (pits, post holes) end at the edge of the terrain. If there was also a trench at this edge, it could no longer be detected because of the shallow excavation pit and the subsequent buildings (north gate).

Stone period I

From 100 AD there was a cohors II Batavorum in Favianis , which in turn was replaced by the cohors I Aelia Brittonum Milliaria in 110 AD . This is probably why the camp was converted into stone, as the latter numbered over 1000 men. In stone period I, a total of two construction phases can be distinguished. The beginning of the erection of the fort walls and possibly also some of the interior buildings in stone falls in the years between 130/150 AD. Further changes within the camp around 170/180 AD are documented by leveling measures and embankments.

So far, no remains have been found for the first phase, but it is assumed that the fort developed similarly to the one in Tulln . In this case, after evaluating the ceramic finds, the following floor plan results:

- the north-west corner was in the area of the rectory,

- the northern front reaches the Nikolaihof in the east,

- the western front stretches to the south and corresponds to the still preserved city wall to the corner of Missongasse - Alte Friedhofstrasse,

- the southern front follows the course of Alte Friedhofstrasse.

If you incorporate all of the information about stone fort I into an overall plan, you get the following result: The size of the first stone fort was 176 × 176 m square, with only the east-west extent secured, that is about three hectares. The expansion of the fort to three hectares probably took place in construction phase 2. For this phase 2, the 1.5 m thick fort wall could be determined, which presumably had several trenches in front of it. The fort wall in the north-west corner has also been archaeologically proven. A warehouse road divided the area into two comparatively equal areas. This gravel road runs from the north gate between the barracks of the rear camp area (retentura) and ends at the south gate. In the years after AD 251 the camp burned down completely; the relevant fire horizon could be touched on in several places. This catastrophe was followed by a significant decrease in imported ceramics and the circulation of coins, which is probably caused by a massive decline in population.

Trench system

In a ditch discovered in 1986, its time position could not be clarified (Roman or medieval), as the medieval city wall exactly follows the fort wall. In 1990 Heinrich Zahbelicky was able to investigate another trench in Hans-Kudlich-Gasse. Following the fort ditch in the old Friedhofsstraße, one probably Roman ditch and two other ditches separated by gravel sediments were observed. The latter two ran in an east-west direction and could be natural origins or former river beds. Their deepest point was 3.5 m below the modern level. Thus, a double trench system can be assumed for stone period I, which may also have included a natural branch of the Danube. A V-ditch was also discovered in the western fortification in 1988, but its chronology is unclear.

Gates and towers

The remains of a gate system could be found directly on the edge of the elevated terrace (Kremserstraße / Kirchengasse). Verena Gassner interpreted the findings as the porta praetoria (north gate) of the camp. A section of the southern gate system was also approached during canal works (Alte Friedhofstrasse). A massive wall pillar and the remains of a wall in the middle could indicate the presence of a spina . The remains of the western camp gate were found in Melker Strasse and showed that the western and eastern gates were obviously not exactly on the central axis of the fort. They must have been in the area in front of the north end of the barracks buildings. Since it is obvious that the north gate was relatively narrow and had only one passage, its interpretation as porta praetoria (main gate) is no longer tenable. The main axis of the fort is likely to have run east-west, analogous to the Limes road. The reconstruction of the stone fort I with the principia in the northern part of the fort area and a relatively wide via decumana additionally supports this assumption (see also the floor plan of the Weissenburg fort ).

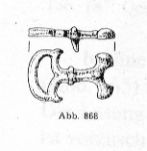

North gate

Some architectural parts of the north gate were exposed (e.g. a swell stone, today set up in front of the Roman Museum, a corbel and a central gate stone). Recesses for a gate pan are worked into two stone blocks recovered from the water pipe (Block I and II), on which concentric grinding marks can be seen. The remains of an iron shoe from the gate pan and the sprue were also preserved in Block I. In places on this stone traces of blackening could also be seen. The smaller, block II, had a profile on its long side in the form of two hollow trowels arranged one above the other with an adjacent edge. A recess for the goal pan is carved out on the underside. A limestone slab 0.08 m thick was inserted in the recess. The blocks were interpreted as corbels of the gate construction.

Gravel layers south of the north gate mark one of the main camp roads. The reconstruction of the north gate from stone period I is only possible to a limited extent. The wall sections of the towers, measured in 1996, differ in width from the fort wall (0.9 to 1.2 m). These different wall thicknesses were evidently quite common, as the comparison with the east gate of the Comagena fort shows (front side 1.2 to 1.3 m, other sides 1.1 m, total width of the gate system 21 m). Most of the Noric gate towers were 0.9 and 1.5 m thick. Christine Ertl speaks of a typical Limes fort site with two square towers that protruded a little from the wall. If the part of the wall of the northern defense that came to light in the area around Nikolaihof was extended to the east tower of the north gate, it would protrude around 1 m in front of the fort wall. A lead of less than a meter would speak for the construction of the gate in the reign of Hadrian . Incidentally, assuming a double-gate passage (with spina ), the entire gate system probably reached a width of around 25 m.

However, it has not yet been clarified whether a double-gate system or even only one gate system can be assumed. A section of the wall running in a north-easterly direction could be part of a spina or it could also belong to the wall of the eastern gate tower. However, according to the interpretation of the available findings, the assumption of a one-gate passage appears to be the most likely variant (15 m wide gate, passage of 4.5 m), a two-gate system would not be axially, but would be slightly shifted to the west and would therefore hardly move into it previously known construction scheme of the camp fit. The north gate of Favianis could best be compared with that of Fort Hesselbach . Its gate construction had only one passage, slightly protruding, rectangular towers and wooden gates with two wings (total width ten meters, passage three meters). Finally, a horizon of destruction with clearly recognizable layers of charcoal ash and a roof tile collapse could be observed at the northern gate.

Northwestern intermediate tower

In order to determine the north wall of the fort, Herma Stiglitz laid out search cuts again in 1952 to the northwest and northeast of the Roman Hall. In the northwest, a north-south search cut started at a stump protruding from the city wall, which was regarded as the remainder of an intermediate tower. In 2007, a rectangular intermediate tower of stone fort I was uncovered, the rising masonry of which was still preserved up to a height of 1.2 to 1.5 m. The rectangular base was 3.4 × 6.3 m, its wall thickness 0.7 m. The connection to the fort wall could not be determined, however, the same applies to the ditch in front of it.

Stone period II

In late antiquity (end of the 3rd century), the fortifications were modernized and reinforced by horseshoe towers (U-towers) and at the corners by fan-shaped towers (U-tower west, U-tower north, U-tower east, U-tower south west wall ). Based on previous experience on the Danube Limes, the design of the fort with four fan towers at the corners appears logical. While the north-west corner tower is still visible, the remains of the wall in the south-west and south-east corners are largely made of medieval material. During an inspection of the house at St. Pöltner Strasse 22 in 1996, the remains of an oval or circular tower on the first floor could be seen. The up to three meters thick walls of the late antique fortifications have been preserved mainly in the western medieval city wall, are still detectable as foundations in the north and were again shown in the east during the excavations in Nikolaihof. A piece of the fort wall can also be seen in the courtyard of St. Pöltner Strasse 20. Here she turns south to a tower.

The multi-phase stone fort II initially covered an area of around 3.06 hectares. Among other things, team barracks and stable buildings, presumably for the horses of an equestrian unit, could be observed on the inside. The last major renovation work was carried out in the time of Valentine, which was mainly recognizable by the generous extension of the fenced area to the north. The fort area, which was initially restricted to the area of the southern gravel terrace, was expanded to include the lower terrace in the north. The course of the new wall is known for the eastern section. The late antique area now comprised about 5.25 hectares and was surrounded by a pointed moat. Since it remained undeveloped except for an island-like hilltop, it can be assumed that in late antiquity it served as a refuge for the surrounding population or as a camp for troops passing through (oppidum vel castellum) . The port of the Danube Flotilla has not yet been proven archaeologically. In the Franziszeischen cadastre from the year 1821, however, an oval parcel near the Danube bank is shown west of the fort area, which might once have been the ancient harbor basin.

In its final phase, the fort turned into a civilian oppidum . The spectrum of finds and the much more irregular construction with mud brick huts suggest the existence of a civilian settlement in the southern part of the fort, while the already strongly decimated garrison force was limited to the northern part. Probably they moved into a - in Norian forts repeatedly encountered - burgus or a radical castle back. The secured access to the ford over the Danube was still important.

Gates and towers

Of the fort gates, only the location of the late antique north gate (Porta praetoria) under the city palace and, through the discovery of a profiled corner cuboid in the cellar of a house in Frauenhofgasse, that of the south gate (Porta decumana) is known. The excavations of 1952 prompted the Federal Monuments Office (Herma Stiglitz) to investigate the area north of the palace between 1965 and 1966, where a gate opening about one meter wide was found further east. The gate was redesigned in late antiquity. A two-phase north-south wall, which was probably part of a tower, also has a distinctive layer of fire with a roof tile lintel. These remains belonged to a flank tower which was destroyed by fire and which was covered with tegulae and imbrices . The gravel strip of the arterial road could also be observed. Herma Stiglitz suspected a Valentine gate system here, but this is not stratigraphically secured. Verena Gassner and Sonja Jilek interpret the foundation as part of a medieval gate tower. This gate system may have been used as a kind of small fortress until the early Middle Ages.

The positions of the western (Porta principalis sinistra) and the eastern gate (Porta principalis dextra) were blurred by the massive renovations to the stone fort II and have remained unknown to date. The east gate was probably on the area of the Nikolaihof, as an ancient arterial road can be proven here - after analyzing the vegetation. According to Stiglitz / Schneider, the west gate is to be looked for south of the western fan-shaped tower, as no continuous wall foundation could be found here despite probes.

Western fan tower

In 1972 the ÖAI (Herma Stiglitz), after removing debris in the parish garden, undertook an archaeological investigation on a wall that had been dated to the Middle Ages and served as a garden pavilion foundation. When inspecting the basement room below and measuring it, a quadrant-shaped floor plan was recognized which belonged to a Roman fan-shaped tower from the 4th century (max. Width 12.4 m, length 14.6 m). Its walls, up to 2 m thick, were preserved up to the first floor. Although this shape is typical for corner towers of this time, it would have made little fortification here. The location of this tower suggests that the north wall was pulled back somewhat from the Danube bank and that the rear part of the fort was significantly reduced in size in late antiquity.

Western horseshoe tower

This tower (dimensions: 11.4 × 14 m, 10 m high) represents the chronologically most recent construction phase of the fort and probably dates from the 4th or 5th century. But it would also be possible that it was only created at the time of Severin. Most of its masonry was only removed in modern times, when its northern flank - probably partially destroyed by floods - was torn down and the gap was closed by a new, sloping wall. Its east wall was removed in the 1930s (when a new garden was being built). There is still a photograph of this wall.

As is usually the case with buildings of this type, the tower was not placed in front of the fort wall. When it was built, a section of the fort wall was torn down. At its rear, the tower protrudes a little into the fort area (see also U-tower of Zwentendorf ) and covered a small hatch. Their remains can still be recognized by a door threshold on the north wall of the tower and in the east at the entrance to the interior of the fort. In 1969, three exploratory cuts (Herma Stiglitz) were made on the outside of the U-tower on the western city wall in order to clarify a possible structural connection with the city wall. Further to the west, another broken wall came to light, which Christine Ertel sees as the foundation of an older tower. In the 1980s, the tower was subjected to a closer inspection. For this purpose, the rubble was completely removed from the interior. A 20 cm thick layer of fire could be found underneath, which was already resting on the protrusion of the foundation. In 1984 Ewald Schedivy carried out a surface excavation and a cut across the entire width in the eastern part in the area of the curvature of the wall. It was made clear that the tower and the fort wall were not built at the same time.

The tower walls, which are up to 2 m wide, are late antique up to the second floor. Rectangular beam holes mark the position of the support beams for the wooden false ceilings, smaller holes those of the scaffolding. The two arched windows on the upper floor are probably also Roman. The interior of the tower was subsequently partitioned off by a 0.9 m wide wall. There was also a staircase here, four of which have been preserved. In some construction details it is very similar to the Burgus von Bacharnsdorf . It was in line of sight to the neighboring watchtowers of Hollenburg (east) and Rossatz (west) and probably also served as a signal tower for the late antique chain of watchtowers. In the Middle Ages, the tower degenerated into a garbage dump.

Eastern horseshoe tower

In 1979 and 1982 the ÖAI (Herma Stiglitz, Ewald Schedivy) examined the western part of the historical building complex around the Agapit Chapel. A cast foundation with partially still rising masonry was recognized. It was interpreted as the remnant of a horseshoe tower.

Burgus or remnant fort

2.6 m west of the building complex around the Agapit Chapel, on the inner edge of a wall curve, there is a 2.5 m thick wall that was cut again in the excavations in 1982 and running north-south (eastern fort wall). A new building in 1982 enabled an excavation to the south of it (Herma Stiglitz, Ewald Schedivy) in the inner courtyard, where this wall could be followed. In addition, seven search cuts were made in the kitchen wing. It turned out that the north wall of the bulk box rests on Roman masonry, which is rounded at the corners. The reconstruction resulted in a 30 × 21 m building, which was identified as the late antique remainder of the fort of Favianis (Stone Period II). Its foundations were up to 2.3 m thick, inside the pillar foundations of a basement and broken roof tiles were found.

Interior constructions

Since Mautern was inhabited continuously from antiquity to the present day, only very little information could be gained about the type, location and condition of the buildings inside the fort. Uncovered remains in the northern part of the fort (praetentura) suggest half-timbered buildings ( barracks and stables) built on stone foundations , which were destroyed by fire. The buildings in the north of the area of the former fort were probably demolished in antiquity for defense reasons. An indication of this came from an excavation before the construction of residential houses in the former garden of the city palace, where a heavy layer of fire could be observed.

Wood-earth period

In the course of the excavation in 2007, traces of pilots and the remains of a team barrack with a stable building in front of the building (foundation trenches, urine collection pits) came to light on the filled trenches of the early fort.

Stone fort I

The construction of the multi-phase stone fort I can also be traced back to the findings of the wall in its camp barracks. The interior structures of the wood and earth fort were almost completely removed between 170 and 180. These new buildings, mostly double barracks separated by a narrow alley, had their own fire pits in the contubernien (from the tent community = eight men) and were raised with clay bricks, following the layout of the previous buildings of the wood-earth period. The associated barracks stood in a north-south direction in the south-western part of the camp area. These, in turn, were destroyed by a fire disaster, as can be seen from a mud brick wall in Frauenhofgasse that had been preserved in the fall position. The wooden beam roof, covered with straw and wooden shingles, fell to the ground. Remarkably, the inventory of a room was almost completely preserved. Its components suggest that military personnel are still being supplied decentrally. The plates and drinking cups made from Terra Sigillata were almost entirely made, the usual finds of utility ceramics were only partially engraved with names. After sorting, they resulted in an almost complete service for eight men. Every soldier must therefore have owned at least two terra sigillata vessels, a mug and a plate. Cooking pots, storage containers and water containers were safely used together per contubernium .

The rising masonry of such interior structures was predominantly built using stone, half-timbered and clay construction. The load-bearing walls made of adobe bricks were plastered inside and out, around two meters high and placed on the stone foundations of the previous buildings, the partition walls consisted of half-timbered structures with plastered rods. Some of the buildings were equipped with a floor screed or wall heating made of so-called tubular bricks and had an arcade in front. The interior walls were plastered with white lime. It is a typical crew barrack with 13 contubernia with the same size papilio with fireplace (bedroom) and arma (armory), a better equipped head building (officers' quarters) with an estimated total length of 64.2 m and an area of 770 m². With these dimensions, the barracks of Favianis are above the average of the auxiliary fort in Noricum (ten contubernia). As with most of the Limes forts, the double barracks was laid out per scama , i.e. parallel to the main camp road (via praetoria) , because the exposed walls in the northern part (retentura) of the area (water pipe cune ) are aligned with the double barracks in Frauenhofergasse ( praetentura , southwestern part). Overall, the praetentura von Favianis would offer space for four double barracks of this size. The reconstruction of these buildings is based on the crew quarters of the forts of Fendoch, Künzing and Hofheim. For buildings of this type, a service life of around 25 years is generally assumed. However, this can be considerably stretched by various measures such as splash protection, felling the tree trunks in winter and pest control. Since no subsequent alterations were discernible within these barracks, they should have existed for an estimated 70–80 years.

During construction work in the houses at St. Pöltner Strasse 25 and 26 in 1956, a 4 × 4 m cellar with two window-like niches and several wall sections were uncovered which could once have been part of the fort's principia . In the further course, walls and fragments of Roman bricks , which may have been part of the interior construction , repeatedly came to light. The basement sat on a 3 m deep and 0.3 m cantilevered foundation. The location of the houses in St. Pöltner Straße corresponds roughly to the middle of the north-south axis of the former fort area and would therefore have been built exactly at the highest point inside the fort. The cellar was classified by Christine Ertel as the flag sanctuary of the fort, but this interpretation seems absurd as it was located in the southern part of the plot and probably belonged to a team barracks or another building. The dimensions of the principia are assumed to be 40 × 30 m. In the Kremser Straße water supply cuneiform, thin-volume walking levels from late antiquity were repeatedly observed, which could be an indication that the building was used until the late period of the fort.

Stone fort II

After 300 AD, there were numerous new buildings in the interior, but its orientation no longer adhered to previous structures and was also disturbed by pits that were built later. Most of the buildings were probably mostly wooden. From the small-scale excavations, however, hardly any conclusions could be drawn about their intended use. The foundations of the buildings of Stone Fort I must still have been visible, they were probably included again in part in the planning.

For the late antique periods of Steinkastell II, a hose heating system with heating ducts, an earthen screed and a threshold beam of a building was documented over a fire protection horizon in 2007, which was built using truss technology and finally destroyed by a fire disaster. The walls and screeds of a building that was placed directly on the inside of the fort wall lay over the former via sagularis .

In the stratum of the post-Valentine period, directly above a horizon of destruction, a tamped clay soil was documented in 2007, which, however, could not be recorded in its entire extent. A wall 1 m wide was built over the interval, running from north to south, which consisted mainly of stone-lime-clay mortar binding stones. The clay screed of a building and a smaller annex could be determined from the findings of the inner tower of stone fort I. In summary, it can be said that the redevelopment of the inner area represents a hiatus in the history of the fort's construction and perhaps also in the use of the area. The development had to meet other needs, but it is noticeable that large parts were no longer built on at all.

Storage boiler

At the beginning of August 2008, during canal construction work at the Kremser Strasse / Melkerstrasse intersection, part of a well-preserved, multi-phase apse of the camp pool was uncovered. It was probably part of the hot bath ( caldarium ) as it was equipped with a hollow brick wall heater ( tubuli ). In structural terms, the construction of the thermal baths is assigned to phases 3 and 4 of the fort (according to Groh / Sedlmayer). The finds in the upper layers dated to the 4th to 5th centuries AD. The smaller apse probably comes from late antiquity. After the sewer work was completed, the remains of the wall had to be filled in again.

garrison

Brick stamps were mainly used to reconstruct the occupancy history of the camp, as they can provide valuable information about which units were used in and around the camp during construction work. If they come from auxiliaries , it is likely that they were also stationed in the camp. Finds of brick stamps from legion formations, on the other hand, only say that their relatives were called in for construction work or that the building material was supplied by this legion. However, these individual findings must not be overestimated, as individual bricks could also have come from other locations. Brick stamps found here mention the Legio X Gemina stationed in Vindobona / Vienna and the Legio XIIII Gemina Martia Victrix from Carnuntum . The members may put these two legions at the time of Stone Camp I for a short time the garrison .

The following crew units are known for Favianis :

| Time position | Troop name | comment | |

| 1st century AD |

Ala (cavalry squadron) |

During the excavations in 2007 (see the section on research history), the remains of larger stables came to light, which speaks for the presence of a horse troop in Mautern. However, the name and number of crews of this unit have remained unknown to date due to a lack of other related finds. | |

| late 1st century AD | Cohors prima Ubiorum (the first cohort of the Ubier ) | Theodor Mommsen and Max Nistler tried to establish a connection with this Ubier cohort by means of found brick stamps (CHOIVB) . The troops were stationed in the Germania inferior until the first half of the 1st century and were transferred to the province of Moesia in the late 1st century . According to Max Nistler, due to Domitian's German wars, she came to Noricum in the 80s of the 1st century and initially settled in Favianis . Hans Riedl also provided support based on the above. Brick fragment a stationing of this cohort in Favianis (before 90 AD) He was however well aware of the low significance of a single brick temple. Herma Stiglitz refused the presence of the Ubier in Favianis. | |

| Mid 2nd century AD |

Cohors secunda Batavorum millaria (the second cohort of Batavians , 1,000 men strong) |

This formation is a so-called cohors millaria , i.e. an approximately 1,000-strong troop of auxiliary infantry , which would explain the relatively large area of the camp. According to the Opinio comunis , the old Batavian cohorts , mentioned in Tacitus , were dissolved by Vespasian after the suppression of the Batavian revolt on the Lower Rhine. The 2nd Bataverkohort was probably a new creation and is documented as part of the Pannonian provincial army until 80 AD. Hannsjörg Ubl suspects that it originally emerged from the merger of two Quinquenaria units (500 men each). A total of three Batavian cohorts can be identified for Britain during the period of the Agricola campaigns . After the campaigns ended, around 110 AD at the earliest, they were likely to have been moved to the Danube. A stay in Moesia in the years 85–86 AD is also likely. According to the inscriptions on the Adamklissi memorial , Batavians were also involved in Trajan's Dacian war . However , it cannot be said with absolute certainty whether the Batavian cohort was stationed in Favianis afterwards and participated in the renovation of the camp. For Herma Stiglitz, the troops were in Favianis from 127/128 up to and including 138 AD. Two military diplomas give a little hint in this direction ; one of them was found in the vicus , was exhibited for the veteran Octavius and dates from the years 131–133 AD, another, discovered in Stein (Stein 4) on the Danube, can be traced back to the years 135–138 AD. To date. Both suggest that this unit was staying in Favianis . Hannsjörg Ubl believes that a station in the Klosterneuburg Fort is possible due to the brick stamps excavated on site . In 1976, the remains of a dedicatory inscription from this cohort were found in the Martinskirche in Linz , which made it possible for this troop to also be present in Fort Lentia . | |

| Mid 2nd to 3rd century AD |

Cohors prima Aelia Britonnum (the first Aelian cohort of the British ) |

The knowledge about the occupation troops from the 1940s onwards is much better. The presence of the British in Mautern is documented by brick stamps up to the 3rd century. Due to the findings of earlier sigillate ceramics, it soon became clear that they could not have been the first garrison force in Favianis . Sufficiently archaeologically documented it is from the 2nd century, as it developed a lively construction activity in Favianis and therefore left behind numerous brick stamps. According to the ID of this brick stamp, she was previously stationed in Wallsee . According to the name, the cohort obviously came from Britain, where it was recruited under the emperors Hadrian or Antoninus Pius . According to the assumption of Franz Kainz, the troops came to the Danube at the time of Mark Aurel . She took over guard duty in this camp around 140/150 AD at the earliest and thus replaced the Cohors II Batavorum . After brick stamps with the imprint COIABANT and HIABAVTO, the unit also bore the honorary name ANTONINIANA, which speaks for its presence in Mautern until at least the beginning of the reign of Caracalla . According to Albrecht Aign, it went into the newly established Legio I Noricorum in the course of the Diocletian-Constantinian army reform . For Josef Aschbach it remained as an independent troop on the Noric Danube until the time of Valentinian I. |

Brick stamp of the Cohors I Aelia Britonnum ( Roman Museum Wallsee-Sindelburg )

|

| 4th to 5th century AD |

a) Legio prima noricorum (the first Noriker legion), b) Liburnarii (marines) |

In the course of the army reform of Diocletian in late antiquity ( fleet members ) of the newly established Legio I Noricorum were moved to Mautern, which is also proven by numerous brick stamps. Also in the section of the Noric Dux in the Notitia Dignitatum a praefectus legionis liburnariorum primorum Noricorum, Fafianae is given for Mautern . It is not known where the Legion was originally located. In its full inventory, it should have comprised around 2,000 men and, according to Notitia Dignitatum, was spread over the forts Wallsee and Favianis . Most likely it consisted of Germanic tribes . The late antique brick stamp finds refer to the last major construction work under the ( Dux ) Ursicinus , the locally responsible section general under Valentinian I. A stationing of the Legion in Mautern is to be regarded as reasonably assured at least until the rule of Valentinian (364-375) according to today's knowledge. |

Brick stamp of the Legio I noricorum , found in Schwechat (Lower Austria). This brick stamp comes from the now lost Widter collection

|

| 5th to 6th century AD | Milites (soldiers / guards) | In Favianis , according to the Vita Sancti Severini, when Severin arrived there was still a regular garrison force under the command of a tribune named Mamertinus . However, he had few and poorly equipped soldiers under his command ( paucissimi milites ). In chapters 4, 1–5 of Severin's Vita, an attack by Ostrogoths on "... people and cattle outside the walls" is described. At the second milestone, however , the Milites succeeded in catching the Eastern Gothic looters on the banks of the Tingutia , probably the Fladnitz near Furth-Palt on the Göttweiger Berg, killing them or capturing them and appropriating all their equipment. The troops were obviously completely on their own and forced to get the necessary supplies in this way. Some of the prisoners were brought before Severin. He apparently concluded a kind of peace treaty with them, which was probably binding for the entire tribal group, and then let them go in free escort. Mamertinus was later ordained a bishop . In fact, between 467 and 488 in the east of Ufernoricum no further Gothic ideas are known. A superordinate Dux or Comes is no longer mentioned in Severin's vita. The Norwegian border army and its administrative organization had probably already completely disbanded by this time - due to the lack of pay payments. Therefore, Romans also entered the service of Germanic rulers, B. a certain Avitianus who served in the retinue of the Rugier king Federuch . |

Vicus

The city center of today's Mautern is almost congruent with the former fort area. This circumstance turned out to be a particular stroke of luck, since it offered better possibilities for investigations on the civilian vicus . The vicus enclosed the fort in an arch extending from west to east and also spread out somewhat to the south. In numerous studies since 1930, villa complexes, apartment buildings, wells, streets and burial grounds have been identified. In the years from 1997 to 1999, the excavation activities concentrated mainly on the investigation of an area of around 7000 m² in the east and a smaller excavation in the south of the camp village. A settlement of around 20 hectares was found, which was inhabited by the craftsmen, traders, merchants and landlords accompanying the units, as well as their families.

development

The development of the building land in the east probably took place around 70 AD. It was preceded by fire clearance. Roads running almost parallel to each other were laid out and the area was divided into strip-shaped plots. The area was measured over an area of 10 to 30 hectares (most likely by military personnel). Economic reasons were probably the main reason for the development of the vicus.

The positioning of the camp village to the west, east and south of the fort determined the topography of the site and the connection to the Limes Road. The individual parcels in the examined section are 39.5 to 40.8 m long and 9.5 to 15 m wide. The first buildings - as in the fort - were erected as multi-room houses using wood and earth technology, the construction techniques used in the fort and vicus are almost identical. The allotment of the parcels was not carried out across the board, but only took place gradually. Individual parcels remained undeveloped in the following periods.

Over time, the two-post hut developed into the dominant type of house in the vicus of Favianis . They were on average 5 to 10 square meters and sunk up to 0.3 m in the ground. The implementation of this local building tradition could be due to an increased influx from the Noric-Pannonian area, which arrived here as a result of an exchange of troops after the departure of the first settlers, or due to a coexistence with the original inhabitants. It is also possible that the individual families lived in the pit houses and that larger clans and their relatives or servants (slaves) occupied the multi-room houses. The majority of the finds from the garbage pits, however, suggest smaller groups of people. The total number of residents should not have exceeded the 3000 mark in the early days.

A well house in a central location and in the immediate vicinity of the metal workshops suggests a good organizational structure of the Vicus. Latrines were obviously used jointly. The arrangement of the craft businesses shows a high degree of division of labor. Most of the multi-room houses were abandoned around 100 AD and fell into disrepair, but the building land that was available again was apparently fallow for some time. After the expansion of the wood-earth fort between 100 and 140 AD, it was surrounded by a 40 m wide glacis, which had to remain free of buildings, but was allowed to be used commercially by the vicus residents. Whereas the craft and living areas were previously clearly separated, the new development scheme shows a different picture. The mine huts are now placed in groups of at least two buildings directly on the street, which indicates a commercial specialization of the individual families. In some cases, new parcels are also being made and the mine hut finally asserts itself as the most distinctive architectural feature of the vicus. During this period, it is necessary to prove that farm animals (sheep, goats, bills and chickens) are kept, the meat of which is used or preserved on site. The population reached its highest level with the expansion of stone fort I with an estimated 4600 people, which corresponds to a ratio of about 1: 4 to the soldiers of the fort. The community is now likely to have been less tightly organized than it was in the early days of the camp village.

The rich finds testify to a high degree of prosperity and a long period of peace, which the residents of the civil settlement were able to enjoy. In their heyday, the houses were consistently furnished with high-quality wall paintings, heating systems and extensive interiors. Particularly noteworthy are the numerous well-preserved cellar buildings, a larger one is on Schubertstrasse, another at Grüner Weg No. 15. This was later integrated into a modern residential building (R. Kurzbauer). The brick cellar uncovered by Herma Stiglitz in 1953 was documented in 1999. The room, measuring approx. 21 × 3.7 m, has been preserved up to a height of 1.8 m. There are four wall niches on the eastern and three on the southern side, which also had a shaft. The limestone walls are mortar and plastered. Such cellars have been exposed over and over again. They were also equipped with plastered walls, screed floors, wall niches or slotted windows. In all of these examples, their function as storage rooms could be clearly recognized; they were not grave facilities ( columbaria ).

A broad layer of fire, which can be dated to the late 2nd century AD by small finds, marks the end of the heyday of the vicus of Mautern and is likely to be due to the turbulent events in the Marcomann Wars. The settlement was largely abandoned and the area of the large workshops was deserted. The disposal of numerous young animal carcasses (pigs, chickens) in the latrines of a tannery could be an indication of the withdrawal of many residents, since young animals were not suitable for eating and would not have survived transport over a long distance. In the northeast of the vicus was u. a. also made a well unusable by filling it with animal carcasses and garbage. Nevertheless, life went on on a smaller scale, the ruins were leveled, which explains the well-preserved basement rooms. Most of the time, half-timbered buildings were raised above the leveling layer, albeit with a simpler design. However, those areas of the vicus that were previously fallow are preferably built first, as the new settlers probably still found the field of ruins and only removed it gradually.

The declining development of the vicus came to an end with the destruction of parts of the fort in the middle of the 3rd century. In the examined part of the vicus, however, there is no layer of destruction. Some of the mine huts were given up before the fire disaster in the fort. The construction type mine hut disappears from the vicus and can only be explained with the recent departure of the population, which is also supported by a deposit (metal depot). Chipped yoke fittings, construction fittings dismantled from buildings and various equipment complete the picture of the vicus' task. The fort was probably unoccupied at that time, as no traces of a fight could be found in the horizon of destruction. The looted fort and vicus will be deserted for an estimated 20 years.

It is not entirely clear whether the camp and the camp service were more or less densely populated without interruption. The arrival of new residents in the vicus is documented by the construction of one-room houses. Two wells up to seven meters deep are dug, which suggests that the water table has fallen. According to evidence of simple hose heating in these 25-30 m² houses, which are typical in terms of their design for the end of the 4th century, there was still brisk construction activity in the vicus at this time. Nevertheless, the vicus shrank to around five to ten hectares and the population dropped to 400 individuals. The production of local pottery (horreumware) is primitive in contrast to bygone times. Metalworking and textile production are mainly practiced as handicrafts. Trade relations are likely to have existed only to a limited extent. Agriculture is still quite well developed and organized.

From the 5th century AD, however, the civil settlement was finally abandoned. The passages in the Vita Sancti Severini relating to Favianis also confirm the relevant archaeological findings. Its residents withdrew to the castle, which had long since ceased to be occupied solely by soldiers, and whose walls offered somewhat better protection. This tendency can be observed across the entire Noric Limes and probably began on a massive scale around 349 AD, when an imperial decree permitted - initially only merited soldiers - to live with their families within the forts.

population

1st century

The design of the earliest house buildings suggests that so-called “camp followers” from the north-west provinces were among the first residents of the vicus. Cultural peculiarities of settlement groups can also be recorded very well on the basis of objects of daily use, here in particular ceramics are of great importance. According to their evaluation (pot and lateneoid bowl shapes) it can be assumed that the majority of the local population resident in the area in the middle of the century came for the most part from the south-east Norse and south-west Pannonian regions. Further clues for this are the markings of the producers and a small sculpture with a recessed painting pattern. The latter is also very similar to the Latobici house urns . Metal processing on site is also important for determining the population in the early settlement phase. The discovery of food with built-in nozzle bricks in the Vicus East in turn refers to the southern Noricum, where a comparable find has so far only been known from the Roman town on the Magdalensberg in Carinthia.

2nd century

In addition to the upright orientation towards south-east Noricum, there was soon an economic connection to Italy and the surrounding area of Iuvavum , as found cups with smooth surfaces and imported ceramics show. In addition, there is an increase in external influences and a strong anchoring of Romanization in the population (e.g. change in cooking practice, increasing merging of Celtic and Roman elements). Immigrants from Southeast Pannonia and West Moesia or Dacia took most of the pottery into operation, had excellent craft skills (mastering firing temperatures up to 1800 ° C) and thus became the main bearers of culture in the late 2nd century. The Italian-Mediterranean way of life also caught on more and more. A clear population exchange in the eastern vicus is also likely to be due to the stationing of the coh. I can be traced back to Aelia Brittonum after the Dacian Wars in Favianis .

3rd century

After the catastrophe of the Marcomann Wars , in which the vicus was almost completely destroyed, a large part of its population fled and was later replaced - to a limited extent - by settlers from southeast Noricum (with connections to Flavia Solva and Cetium / St. Pölten). These withdrew after a fire disaster, so that settlement activity in the vicus came to a complete standstill for about 20 years.

4th century

Again influx of Southeast Norikers and probably also Pannonians who introduced a new type of house, the one-room house. The architecture and settlement structure suggest that individual families will be resettled. This time the settlers came increasingly from the area around Celeia . The military is very prominent in the culture of this group. This is likely to be related to the stationing of the legio I Noricorum in the reign of Diocletian.

5th century

Germanic tribes settled in neighboring Pannonia since the last third of the 4th century. Around 378 AD, Goths also appeared there, Suebi and Marcomanni can be seen for the first time around 396 in the region between Klosterneuburg and Vienna. In 403 Alaric's Visigoths passed through Noricum, who were replaced by the Huns around 433. After 455, Goths settled in the province again. Due to all these incursions and migrations, the population composition of Noricum was subject to constant change. As a result, although a multi-layered mixture of peoples emerged in a few decades, a large part of the ancestral Romanesque population up to 488 asserted itself in their settlements along the former Danube border.

Socially superior classes of the population ( honestiores ) are hardly mentioned in Severin's vita. Above all, a wealthy widow, Procula, another, Primenius, a follower of Orestes, must have been a refugee from Italy. By the middle of the 5th century, this section of the population had completely disappeared from Noricum. Slaves are also rarely mentioned. Severin once jokingly referred to himself as a slave. They are only mentioned at the court of the rugier king and one in the entourage of Stilicho . Full-time traders and merchants were in fact no longer available, supra-regional trade seems - if at all - to have only been pursued as a sideline. Mainly bartering with natural products was carried out at the weekly markets, but coins were still in use in small amounts. Otherwise, the Vita reports only on very difficult olive oil imports from Italy.

The majority of the population, including many veterans, lived exclusively from agriculture, they became increasingly poor in the course of the 5th century. Eugippius writes that “... hunger is the greatest agony in life.” The late antique layer in Frauenhofgasse contained, among other things, bone material from four small children who had died between the ages of two and six. One of them also showed clear signs of deficiency symptoms and illnesses. Severin introduced a tithe to alleviate this need in order to reduce social tensions and to strengthen the solidarity of the Romans with one another.

Vicus east

During the large-scale excavations in Vicus Ost, a very complex multi-phase development was examined using ten strip-shaped plots. The extent of the vicus can be traced up to 400 m east and south-east of the fort, followed by a burial ground that stretches for about a kilometer along the road to Traismauer . After the forest was cleared by fire around AD 70, it was divided into parcels that followed the main road in their alignment.

As part of a large-scale project, up to 20,000 Roman finds from 600 objects in the eastern vicus were evaluated between 2000 and 2002. This analysis resulted in a periodization of the development of the camp village from the last third of the 1st to the 4th century, which largely corresponds to the events in the fort. The economic fundamentals of the vicus were of particular interest. If large-scale iron processing can be demonstrated in large areas for the early settlement, there will be a complete change in management for the middle decades of the 2nd century, as can be seen from two parcels. This is shown by the findings of four pottery kilns and a high number of false fires and damaged finished products. But the proportion of imported goods among the ceramic finds was also relatively high.

Most of the workshops were used for metal processing, but were supplemented by many other companies. Local ceramic production was heavily influenced from outside. The heyday of this vicus began around 130 AD and lasted until 160 AD. During this period, the area also shows the highest intensity of use (up to 4,000 residents in the entire vicus area). This can be clearly seen in the massing of ceramics and pottery kilns. In the years after 160/170 parts of the vicus were abandoned. Dilapidated houses were later seized and rebuilt by new settlers, who probably also came from the southeast of Noricum. However, there is no extensive destruction horizon around 250 AD, only isolated layers of fire suggest a major catastrophe that left the vicus almost uninhabited for two decades. After that, a new settlement began, albeit to a greatly reduced extent (approx. 400 residents), which can be traced until 370 AD. In the last phase of the eastern vicus there was a comprehensive restructuring of the settlement structure, but the archaeological finds cannot give a direct indication of the economic background to this development. After the settlement area east of today's Burggartengasse was leveled, it was used as a burial ground from late antiquity.

Vicus West

The first ancient settlements came to light in the west of the fort as early as the 1950s. In the area of the secondary school, several excavations were carried out from 1971, which brought evidence of pre-Roman settlement to daylight. Subsequent excavations in the area of Melkerstrasse in the years 2000–2006 show that the settlement area was built according to plan. Here it could also be proven that the development of the 3rd to 4th century is not related to the previous building grid.

The oldest settlement remains (first half of the 1st century) have been found in the western vicus. Its planned development corresponds to an orthogonal grid, the strip houses are aligned with the streets. This vicus obviously reached its greatest extent in the 2nd century. A new building took place towards the end of the 2nd / beginning of the 3rd century, as shown by smaller cellars and numerous pits. The foundations of stone houses are also known from this period. Traces of late antique building as well as those of a pottery kiln can be found near the western wall of the fort. In some areas the area was also used as a burial place in late antiquity.

Vicus south