Dacian Wars

As Dacian Wars several military conflicts between the people of the are Dacians and the expanding Roman Empire under the emperors Domitian (81-96) and Trajan designated (98-117). They ended with the annexation of Dacia by the Romans. The Dacians lived in the Carpathian Mountains in what is now Romania .

prehistory

The first two years of the reign of Emperor Domitian (81–96) were marked by domestic political problems that led to the first wave of exiles and executions. The victims of this purge included Titus Flavius Sabinus and a number of men who had been close to Domitian's late brother Titus (79-81). In 83 Domitian went to Mogontiacum , today's Mainz, to wage a war of aggression against the Chatti from there. This action was justified with the general threat to the province, which emanated from these tribes. At least as important for Domitian was the associated opportunity to strengthen his domestic political position by demonstrating his virtus imperatoria and victoriousness. The campaign was successful and ended with the deditio , the unconditional submission of the Chatti. Domitian took on the victorious name Germanicus and had coins minted with the inscription "Germania capta". Connected with the latter was the conversion of the Germanic military districts into the two provinces Germania superior and Germania inferior . The territorial gains were not considerable, rather it was about the rounding off of already won areas in southwestern Germania (in the area of the Neuwied Basin , the Taunus and the Wetterau as well as the merger with the Dekumatland ). Nevertheless, Domitian propagated that with this he had achieved a success that even Augustus had failed. Domitian's increasingly tough attitude towards the tribes and federates in the run-up to the empire may have contributed to the Dacian prince Diurpaneus founding an anti-Roman coalition, which invaded the Roman province of Moesia either in winter 85/86 or not until summer 86 . The exact circumstances are unknown. The provincial governor Gaius Oppius Sabinus was killed in the fighting that followed, the Roman auxiliary camps on the Danube were overrun and looting and pillage took place in the province.

The Dacian Wars of Domitian

Domitian immediately had troops from the surrounding provinces (including Pannonia and Upper Germany ) gather together and went to the front in person. The new imperial acclamations of the emperor indicate that the invaders could be thrown back across the Danube in 85. Domitian then retired to Rome and celebrated a triumph in early 86 . In order to avenge the defeat of Sabinus, the Roman troops set out on a punitive expedition to the Dacian region in the summer of 86 under the leadership of the Praetorian prefect Cornelius Fuscus . The Danube was probably crossed by a ship bridge at Oescus . The army then moved north along the course of the Aluta (Olt) towards the Southern Carpathians. At the Rotenturm Pass, however, Fuscus was crushed. He lost his life in battle. The complete equipment of his army as well as numerous prisoners fell into the hands of the Diurpaneus. This renewed defeat diminished the Roman reputation with the Danube tribes and also weakened the domestic political position of the emperor. Therefore Domitian returned later that year to Moesia back. In the following campaign, which was led by Cornelius Nigrinus , Diurpaneus could be eliminated. At the end of 86 the emperor was back in Rome, but this time he did without a victory celebration.

Another event within Dacia was soon to give the conflict a decisive turn: Duras, the prince of a south-west Dacian kingdom, had resigned around the year 85 in favor of his relative Decebalus . At this point it should be noted that some reconstructions of the events do not assume that the diurpaneus was eliminated in 86. Instead, it is considered likely that the resigned Duras is to be equated with Diurpaneus (similar to the portrayal of Karl Christ ). Karl Strobel , however, firmly rejects this interpretation. With Decebalus, a politically and militarily highly qualified person came to the throne who had great negotiating skills and charismatic traits. After Decebalus had remained neutral in 86, it soon became apparent that no agreement could be reached regarding his status as client prince. Domitian reacted with massive restructuring in the Danube provinces and new war plans. A year later, the legate Tettius Julianus tried to advance from the Banat to Sarmizegetusa (Regia) , the Dacian power center. Despite several successes ( e.g. with Tapae ) the campaign was broken off. Reasons for this may have been high Roman losses or simply the too far advanced season.

During the battles for Dacia, the Germanic tribes of the Quadi and Marcomanni had not fulfilled their obligation to provide the Romans with troops, which resulted in the collapse of the federate system in this area. The danger posed by these unfaithful tribes prompted Domitian to undertake a punitive expedition to the Barbaricum before the planned Dacian War in 89 , which however failed ( 1st Pannonian War ). The Marcomanni put the Roman troops to flight, which now also moved the Jazygen to enter the war. This defeat weakened Domitian's reputation in Rome particularly strongly, since he himself was present at the front and the failure could therefore be blamed on himself. The gap between the self-stylization of the victorious emperor and reality grew in spite of many individually rational acts of government.

After these numerous setbacks, Domitian had no choice but to offer Decebalus a compromise peace in 89 to buy time. A central point of the compromise was the recognition of Decebalus as vassal king of all Dacia. In addition, it included the payment of subsidies to Decebalus and the transfer of civil and military technology. Only this peace treaty allowed Decebalus to create an all-Dacian kingdom; the first since the empire of the Burebista († 44 BC). In the following years Domitian tried diplomatic means to set up a second front against the Marcomanni and Quadi in their rear. The two threatened tribes responded by renewing their alliance with the Jazygens, who invaded Roman territory in 92. After the Legio XXI Rapax was wiped out by them, Domitian rushed back to the front in person to stabilize the situation. His victory over the Jazygen was complete, so that this people rose against Rome only in 107/108, when they saw themselves betrayed by Trajan. The subsequent battles against Marcomanni and Quadi could not lead to any satisfactory result and ended with an armistice ( 2nd Pannonian War ).

Preliminary remark on Trajan's Dacer Wars

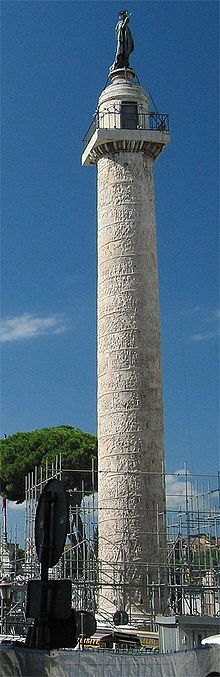

Many of the events of the Dacian Wars of Trajan are depicted on the reliefs of Trajan's Column in Rome. However, the interpretation of these pictorial testimonies is not easy, since the representations also served propaganda purposes and are often idealized. In addition, there is the fact that many written sources on Trajan's era have been lost, for example the Commentarii de bellis Dacicis by Trajan himself. The written sources that have survived offer rather sparse information. On the reverse of Trajan's coins, however, there are very frequent references to his victory over the Dacians.

The first Dacian War of Trajan 101/102

Emperor Trajan (98–117), who also required a convincing military success in order to legitimize his rule, began preparing for the next Dacian war as early as the year he took office. The rich gold and ore deposits of Dacia are likely to have provided a further incentive to conquer the country, although this aspect should not be overestimated. The preparations for war also included a massive expansion of the infrastructure in the affected regions. Important in this context is the straightening of the Donausüdstraße through the completion of an artificial road already begun under Tiberius (14–37) through the rocky regions on the southern bank of the Danube in the area of the Iron Gate (the Tabula Traiana still gives evidence of this today). Since the rapids of the Iron Gate were also a major problem for shipping, a 3.2 km long and 30 m wide ship canal was also built in this area.

The Marcomanni and Quadi had already returned to the federation relationship in 98, after they had been defeated by the Romans during the reign of Nerva in the 3rd Pannonian War . When Trajan asked them to deploy troops, they stuck to their agreements. This was of the utmost importance to Trajan, as it also averted the danger of multi-front war (especially since the Parthian front was also calm at this point ). This made it possible for Trajan to provide strong units of the Imperial Army for the coming Dacian War (7 legions and numerous auxiliary troops and vexillations). The campaign began in 101. The emperor's main force set out from Viminatium (east of Belgrade ) and crossed the Danube by means of a pontoon bridge at Lederata . The advance in the enemy territory was rather slow, as the Romans gradually expanded and secured the conquered area. At Tapae there was the only field battle of this campaign, as Decebalus had avoided an open confrontation up to this point. When the Dacian defeat became foreseeable, Decebalus withdrew his troops in an orderly manner. At the same time, the Dacian offensive began in the area of the lower Danube, which was carried out together with the allied Roxolans . However, the Roman forces were strong enough to win this two-front war. In doing so, Decebalus had missed his most important war goal. He hadn't succeeded in forcing Trajan to evacuate Dacia. As a monument to celebrate the victory over the invaders in Moesia, the Romans built the Tropaeum Traiani near Adamklissi .

In the spring of 102 Trajan resumed the fighting. He himself advanced with the main force via Tapae in the direction of Sarmizegetusa, while the submösischen armies attacked the area of the southern Carpathians. After three successful field battles, Trajan's troops were finally able to storm the Dacian fortress near Costeşti. Around the same time, the Roman commander Manius Laberius Maximus conquered another Dacian dominion center (probably near Tilişca.). After this fighting, the Dacer king offered his submission, but was able to negotiate relatively favorable conditions: Decebalus was allowed to keep the highlands, but had to razor his fortresses. The 1st Dacian War of Trajan was thus over. Despite all the successes, it was also clear here that the expected great Roman victory had not materialized, a circumstance that was probably due to the increasing exhaustion of the Roman troops. In the period that followed, the Romans further expanded their positions in the occupied territories. At the place of the later Colonia Ulpia Traiana Sarmizegetusa a large legionary camp was built (note that this is not the place of the Dacian Sarmizegetusa (Regia)). Another extremely important work was the construction of the 1.2 km long Danube bridge at Drobeta under the direction of Apollodor of Damascus in the years 103-105, a masterpiece of ancient architecture.

The second Dacian War of Trajan 105/106

After further extensive armament, Trajan began his 2nd Dacian War in 105 with around 15 legions and numerous auxiliary associations. Decebalus, to whom the Roman preparations for war had not remained hidden, had in turn had the mountain fortresses repaired and driven the Jazygens from the formerly Dacian areas on the upper and middle Theiss, which had been lost to them in Trajan's first Dacian war. In 105 he responded with a preemptive strike against the Roman positions on his territory. According to the photo report of the Trajan Column, he seems to have managed to break into some auxiliary camps. The large legionary camp on the site of the later Colonia Ulpia Traiana Sarmizegetusa, however, was damaged but could not be stormed. With a bogus offer of surrender, Decebalus then succeeded in capturing the Roman commander Pompey Longinus . His attempt to put Trajan under pressure with this failed when Longinus took his own life. Trajan managed to bring the situation back completely under control, so that Decebalus was hardly capable of offensive warfare against the superior Roman forces in the year 106. Presumably, the large military camp near Apulum was also built in 105 , which sealed off the remaining area of Decebalus from the north. The Trajan column shows in the pictures at the beginning of the offensives in the year 106 that numerous parts of the population and former allies of Decebalus now defected to Trajan, which of course was evaluated by the Romans according to propaganda.

The Romans now fought systematically against Sarmizegetusa. An offer of surrender by Decebalus was refused, so that the Dacer king was forced to give up Sarmizegetusa shortly afterwards. In a remote fortress, which has not yet been clearly located, he tried to organize the last resistance. But even this was only a short interlude. With a few confidants, Decebalus tried to escape to the north in the end. But the auxiliary riders of the Ala II Pannoniorum Veterana under the leadership of NCO Tiberius Claudius Maximus finally caught up with him. To avoid capture, Decebalus cut his throat. This scene is depicted on Trajan's Column, but Tiberius Claudius Maximus could only be identified when his tombstone was discovered in northern Greece in 1965. As a reward for bringing the Decebalus' head to Trajan, Maximus was promoted to Decurio .

The establishment of the Roman province of Dacia

In the defeated Dacia a Roman province was created that had little in common with the fallen Dacian empire. In fact, it has often been assumed that Trajan had almost the entire Dacian people either deported or killed in order to subsequently repopulate the country. This is probably an exaggeration, although there were major changes in the population structure: While many sections of the population and also members of the Dacian elites may have sided with the Roman Empire, the old hierarchies have been eliminated. The central Dacian places were dissolved and smaller, now village-like settlements were built in their place. All old aristocratic residences were also destroyed. Also impressive is the almost complete disappearance of the old Dacian religions even in the run-up to the new Roman province. Large parts of the armed male population who had not become prisoners of war were drafted into the Roman army; a common method of reducing the military capabilities of a defeated tribe while increasing the strength of the Roman army.

There was also the influx of Roman settlers and the settlement of veterans in the area of the new province. So in 109 Colonia Ulpia Traiana Sarmizegetusa was founded on the site of the already mentioned legionary camp. The province saw its first decisive crisis as early as 116 when the Roxolans and Jazygen began again with new attacks on the Roman territory. Since a large part of the army was either bound by the great Jewish uprising and the increasingly disastrous Parthian campaign of the emperor in the east of the empire, only insufficient resistance could be put up. Only Trajan's successor Hadrian (117-138) should succeed in stabilizing the situation again, albeit with the abandonment of the peripheral areas of the province in great Wallachia and on the lower Mureş. Central Dacia remained a Roman province until it was abandoned by Emperor Aurelian (270–275). In their place he raised in Moesia province Dacia Ripensis one, to which later south of that province Dacia mediterranea came. The earlier assumption of a continuity of a Dacian-Roman population after the abandonment of the province in the area of today's Romania is controversial in recent research.

literature

- Constantin Daicoviciu : Dacia and Rome in the Princely Period. In: Rise and Fall of the Roman World . (ANRW). Volume II.6, 1977, pp. 889-918.

- Nicolae Gudea : The Limes Dakiens and the defense of the Upper Moesian Danube line from Trajan to Aurelian. In: ANRW. Volume II.6, 1977, pp. 849-887.

- Nicolae Gudea, Thomas Lobüscher: Dacia . Philipp von Zabern, Mainz 2006, ISBN 3-8053-3415-X .

- Brian Jones: The Emperor Domitian. Routledge, London 1992, ISBN 0-415-10195-6 .

- Karl Strobel : Emperor Trajan An epoch in world history . Verlag Friedrich Pustet, Regensburg 2010, ISBN 978-3-7917-2172-9 .

- Karl Strobel: Domitian's Danube Wars. (= Antiquitas. Row 1, 38). Habelt, Bonn 1989, ISBN 3-7749-2368-X .

- Karl Strobel: Investigations into the Dacer wars of Trajan. Studies on the history of the middle and lower Danube region in the High Imperial Era. (= Antiquitas. Row 1, 33). Habelt, Bonn 1984, ISBN 3-7749-2021-4 .

Web links

Individual evidence

- ^ Karl Strobel: Emperor Traian. An epoch in world history . Verlag Friedrich Pustet, Regensburg 2010, ISBN 978-3-7917-2172-9 , p. 74 ff .

- ↑ Karl Christ: History of the Roman Empire. CH Beck Verlag, Munich 2002, ISBN 3-406-36316-4 , p. 266.

- ^ A b Karl Christ: History of the Roman Empire. CH Beck Verlag, Munich 2002, ISBN 3-406-36316-4 , p. 269.

- ^ Karl Strobel: Emperor Traian. An epoch in world history . Verlag Friedrich Pustet, Regensburg 2010, ISBN 978-3-7917-2172-9 , p. 79 .

- ↑ Cornelius Tacitus: Dialogus de oratoribus. Published by Dieter Flach. Franz Steiner Verlag, Stuttgart 2005, p. 17.

- ↑ Wolfgang Czysz : Gontia: Günzburg in Roman times. Likias-Verlag, 2002, p. 74.

- ^ Karl Strobel: Emperor Traian. An epoch in world history . Verlag Friedrich Pustet, Regensburg 2010, ISBN 978-3-7917-2172-9 , p. 89-90 .

- ^ Karl Strobel: Emperor Traian. An epoch in world history . Verlag Friedrich Pustet, Regensburg 2010, ISBN 978-3-7917-2172-9 , p. 89-91 .

- ^ A b Karl Christ: History of the Roman Empire. CH Beck Verlag, Munich 2002, ISBN 3-406-36316-4 , p. 272.

- ^ Karl Strobel: Emperor Traian. An epoch in world history . Verlag Friedrich Pustet, Regensburg 2010, ISBN 978-3-7917-2172-9 , p. 91 .

- ^ Karl Strobel: Emperor Traian. An epoch in world history . Verlag Friedrich Pustet, Regensburg 2010, ISBN 978-3-7917-2172-9 , p. 93 .

- ^ Karl Strobel: Emperor Traian. An epoch in world history . Verlag Friedrich Pustet, Regensburg 2010, ISBN 978-3-7917-2172-9 , p. 92 .

- ^ Brian Jones: The Emperor Domitian. Routledge, London 1992, ISBN 0-415-10195-6 , p. 226. Footnote 78.

- ↑ Nicolae Gudea - Thomas Lobüscher: Dacia. Philipp von Zabern, Mainz 2006, p. 15.

- ↑ Karl Christ: History of the Roman Empire. CH Beck Verlag, Munich 1995, ISBN 3-406-36316-4 , p. 272.

- ^ Karl Strobel: Emperor Traian. An epoch in world history . Verlag Friedrich Pustet, Regensburg 2010, ISBN 978-3-7917-2172-9 , p. 233 .

- ^ Karl Strobel: Emperor Traian. An epoch in world history . Verlag Friedrich Pustet, Regensburg 2010, ISBN 978-3-7917-2172-9 , p. 96 .

- ↑ Karl Christ: History of the Roman Empire. CH Beck Verlag, Munich 2002, ISBN 3-406-36316-4 , p. 272.

- ↑ Karl Christ: History of the Roman Empire. CH Beck Verlag, Munich 2002, ISBN 3-406-36316-4 , p. 274.

- ^ Karl Strobel: Emperor Traian. An epoch in world history . Verlag Friedrich Pustet, Regensburg 2010, ISBN 978-3-7917-2172-9 , p. 228 .

- ^ Karl Strobel: Emperor Traian. An epoch in world history . Verlag Friedrich Pustet, Regensburg 2010, ISBN 978-3-7917-2172-9 , p. 89-91 .

- ↑ Kate Gilliver: The Augustan Reform and the Structure of the Imperial Army. In: Paul Erdkamp: A Companion to the Roman Army . Blackwell, Oxford-Malden 2007, ISBN 978-1-4051-2153-8 , p. 183.

- ^ Karl Strobel: Emperor Traian. An epoch in world history . Verlag Friedrich Pustet, Regensburg 2010, ISBN 978-3-7917-2172-9 , p. 14 .

- ^ Karl Strobel: Emperor Traian. An epoch in world history . Verlag Friedrich Pustet, Regensburg 2010, ISBN 978-3-7917-2172-9 , p. 227 .

- ^ Karl Strobel: Emperor Traian. An epoch in world history . Verlag Friedrich Pustet, Regensburg 2010, ISBN 978-3-7917-2172-9 , p. 190 .

- ^ Karl Strobel: Emperor Traian. An epoch in world history . Verlag Friedrich Pustet, Regensburg 2010, ISBN 978-3-7917-2172-9 , p. 220 .

- ^ Karl Strobel: Emperor Traian. An epoch in world history . Verlag Friedrich Pustet, Regensburg 2010, ISBN 978-3-7917-2172-9 , p. 244 .

- ^ Karl Strobel: Emperor Traian. An epoch in world history . Verlag Friedrich Pustet, Regensburg 2010, ISBN 978-3-7917-2172-9 , p. 246 .

- ^ Karl Strobel: Emperor Traian. An epoch in world history . Verlag Friedrich Pustet, Regensburg 2010, ISBN 978-3-7917-2172-9 , p. 246 .

- ^ Karl Strobel: Emperor Traian. An epoch in world history . Verlag Friedrich Pustet, Regensburg 2010, ISBN 978-3-7917-2172-9 , p. 259-260 .

- ^ Karl Strobel: Emperor Traian. An epoch in world history . Verlag Friedrich Pustet, Regensburg 2010, ISBN 978-3-7917-2172-9 , p. 250 .

- ^ Karl Strobel: Emperor Traian. An epoch in world history . Verlag Friedrich Pustet, Regensburg 2010, ISBN 978-3-7917-2172-9 , p. 254 .

- ^ Karl Strobel: Emperor Traian. An epoch in world history . Verlag Friedrich Pustet, Regensburg 2010, ISBN 978-3-7917-2172-9 , p. 265 .

- ^ Karl Strobel: Emperor Traian. An epoch in world history . Verlag Friedrich Pustet, Regensburg 2010, ISBN 978-3-7917-2172-9 , p. 264 .

- ^ Karl Strobel: Emperor Traian. An epoch in world history . Verlag Friedrich Pustet, Regensburg 2010, ISBN 978-3-7917-2172-9 , p. 268 .

- ^ Karl Strobel: Emperor Traian. An epoch in world history . Verlag Friedrich Pustet, Regensburg 2010, ISBN 978-3-7917-2172-9 , p. 274 .

- ^ Karl Strobel: Emperor Traian. An epoch in world history . Verlag Friedrich Pustet, Regensburg 2010, ISBN 978-3-7917-2172-9 , p. 278 .

- ^ Karl Strobel: Emperor Traian. An epoch in world history . Verlag Friedrich Pustet, Regensburg 2010, ISBN 978-3-7917-2172-9 , p. 279 .

- ^ Karl Strobel: Emperor Traian. An epoch in world history . Verlag Friedrich Pustet, Regensburg 2010, ISBN 978-3-7917-2172-9 , p. 291 .

- ↑ Karl Christ: History of the Roman Empire. CH Beck Verlag, Munich 2002, ISBN 3-406-36316-4 , p. 301.

- ^ Karl Strobel: Emperor Traian. An epoch in world history . Verlag Friedrich Pustet, Regensburg 2010, ISBN 978-3-7917-2172-9 , p. 293 .

- ^ Karl Strobel: Emperor Traian. An epoch in world history . Verlag Friedrich Pustet, Regensburg 2010, ISBN 978-3-7917-2172-9 , p. 294 .

- ^ Karl Strobel: Emperor Traian. An epoch in world history . Verlag Friedrich Pustet, Regensburg 2010, ISBN 978-3-7917-2172-9 , p. 297 .

- ^ Karl Strobel: Emperor Traian. An epoch in world history . Verlag Friedrich Pustet, Regensburg 2010, ISBN 978-3-7917-2172-9 , p. 393 .

- ^ Karl Strobel: Emperor Traian. An epoch in world history . Verlag Friedrich Pustet, Regensburg 2010, ISBN 978-3-7917-2172-9 , p. 412 .

- ^ Karl Strobel: Emperor Traian. An epoch in world history . Verlag Friedrich Pustet, Regensburg 2010, ISBN 978-3-7917-2172-9 , p. 290 .