Vindobona

| Legion camp Vienna | |

|---|---|

| Alternative name |

a) Vindobona , b) Vindomana , c) Vendobonae , d) Vindomarae |

| limes | Upper Pannonia |

| section | Route 2 |

| Dating (occupancy) |

Domitian , 1st to 5th centuries AD |

| Type |

a) Legion camp, b) Fleet fort |

| unit |

a) Legio XV b) Legio XIII c) Legio XIIII d) Legio X e) Classis Histrica |

| size | approx. 18 ha, 400 m × 500 m |

| Construction | Stone fort, square system with rounded corners |

| State of preservation | ground monument no longer visible above ground |

| place | Vienna |

| Geographical location | 48 ° 12 ′ 39 ″ N , 16 ° 22 ′ 13 ″ E |

| Previous | Klosterneuburg Fort (west) |

| Subsequently | Ala Nova Fort (east) |

Vindobona is the collective name for a Roman legionary camp , a military settlement and a civil town on the middle Danube Limes , in the area of today's federal capital Vienna in Austria . The legionary camp served to protect and monitor the imperial border and road connections to the Barbaricum and the rear of the empire. Although the dense, modern overbuilding considerably hindered the exploration of this site, the outlines of the camp and also the positions of some of its interior structures and the civil settlements could be determined without a doubt.

Vindobona owes its development to one of the most important Roman cities and legionary locations in Upper Pannonia, among other things, to its favorable geographical location between the eastern edge of the Alps and the Pannonian region and the old European traffic axes, the south-north axis along the edge of the Alps ( amber road ) and the west-east axis along the foothills of the Alps and the Danube as a waterway. Civilian settlements and legionary camps stood on the south bank of the Danube. The river was relatively easy to cross at Vindobona , because there it fanned out into numerous meandering arms with gravel islands raised by the water in between.

The city and the legionary camp belonged to the territory of the Roman province of Pannonia and was thus the legionary location furthest to the west. A tombstone of a member of the Legio XV Apollinaris and remains of a wood-earth fortification suggest a first Roman base on the Limes road from the early 1st century AD at the latest. Legion camps and civil settlements have been traceable since the late 1st century AD. In the 1st and 2nd centuries there was possibly a cavalry fort to the northwest of the legionary camp. At times, up to 6,000 soldiers were probably stationed in the camps.

The legionary fortress, located directly on the bank of an arm of the Danube, was also surrounded by a Canabae Legionis (military town) since the late 1st century . At the same time, a civil town was built southeast of it and it expanded rapidly. It is estimated that around 30,000 people lived in and around Vindobona in its heyday from the 2nd to the first half of the 3rd century . The civil city probably also acquired the legal status of an autonomous city of the second order ( Municipium ) in the early 3rd century .

In the 4th century the headquarters of the commander of the Danube Fleet ( Classis Histrica ) was moved from Carnuntum to Vindobona . After its suburbs were destroyed, the legionary camp existed as a fortified settlement until the beginning of the 5th century and was then finally abandoned by the army. Although the traces of Roman settlement also end in this time, Vindobona was probably not completely destroyed or abandoned. A remaining population persisted into the early Middle Ages. The Roman ruins were then almost entirely removed by stone robbery or filled in. During emergency excavations as a result of construction work or the like, archaeologists repeatedly come across the ancient past of the Austrian capital.

Location and topography

Vienna is located on the northeastern foothills of the Alps , in the Vienna Basin directly on the banks of the Danube, one of the most important European west-east connections of antiquity. A steady westerly current ensures a pleasant climate almost all year round. The Vienna Basin is bounded in the west by the Vienna Woods (mons cetium) , which extends as far as the Danube at the Wiener Pforte . Vindobona was initially part of the neighboring Noricum. But because of the constant danger from barbarian invasions, it was annexed to Pannonia in its section under Tiberius . After the province was divided into Pannonia superior (Upper Pannonia) and Pannonia inferior (Lower Pannonia) under Trajan , the place first came to Pannonia Superior and, after the administrative reform of Diocletian, belonged to the newly founded Pannonia Prima (Diocese of Illyria).

In ancient times this landscape was covered by dense riparian forest vegetation . Most of the Celtic settlements were still surrounded by extensive forests. The streams coming from the Vienna Woods and flowing into the Danube provided sufficient fresh water and made access to the river bank easier. The river favored the procurement of food and the transport of commercial goods. The rich fish stocks in the waters were a safe and almost inexhaustible source of food for the residents. The widely branched, marshy tributaries of the Danube and the dense vegetation protected their settlements from the north. Deposits from Ice Age glaciers gave rise to tertiary gravel terraces with loess overlays, the layers of which rise in steps towards the edge of the Vienna Woods and are ideally suited as settlement sites.

The dwellings were mostly built on such hills, and the legionary camp also stood on a river gravel terrace protected from flooding, bounded by the Ottakringer Bach ( Tiefer Graben ) in the west, the Möhringbach in the south and the river bed of the Vienna (Acaunus) and east. The Ottakringer Bach also saved the excavation of the western camp trench. In the north, the bank of the Danube followed, which roughly corresponded to the current course of the Danube Canal . The outline of the legionary camp can still be clearly seen in the street grid of the 1st district, as the Babenberger dukes included the camp wall for the most part in their fortifications. It partially served as a city wall until the late 12th century. The Canabae legionis from the Middle Imperial Period spread out in a semicircle in the west, south and east around the camp. The civil town stood east of the Vienna River, in today's 3rd district . At Vindobona, those passing through had the possibility of a relatively comfortable Danube crossing and extensive bypassing of the impassable Alps. From there, heavily frequented trade routes also led to the Alps, the Alpine Foreland, Bohemia, the Carpathians, the Pannonian Plain and further to the east of the Roman Empire. To the south, one could quickly get to northern Italy over the wide plain of the Vienna Basin and easy-to-pass low mountain ranges.

Road links

Several ancient street finds in Vienna were recognized early on as originating from Roman times. Friedrich von Kenner in particular made an effort to document the ancient road network precisely. In recent excavations, too, street pavements were repeatedly cut ( Michaelerplatz , Palais Harrach , Freyung ). Milestones were set up in sections along the edges to provide information for travelers, for propaganda purposes and as a kind of proof of performance for road construction work by the Roman emperors . Five of them were found in Inzersdorf , which gave the distance from Vindobona to be four Roman miles. According to the inscriptions, the streets were laid out or renovated during the reigns of Antoninus Pius (2nd century), Septimius Severus , Gallienus and Valerian (3rd century), mostly in preparation for major campaigns. The road layouts also had a major impact on the development of Vindobona's settlement. Based on the findings, it was clear that the development started primarily on the main streets. Vindobona stood near the intersection of the Amber Road near Carnuntum , which led from Northern Europe across the Vienna Basin to the Mediterranean Sea ( Adriatic Sea ), with the Limes Road (via iuxta Danuvium) , which connected the western and eastern halves of the empire along the right bank of the Danube. The Limesstraße reached the urban area near Heiligenstadt , and its course in today's inner city of Vienna is largely secured. On Rennweg it met the via decumana leading out of the south gate , which connected Vindobona with Scarbantia (Szombathely). At today's Ringstrasse there was a junction to Aquae ( Baden ), which was probably also used as a spa for the garrison of the legionary camp. The road then led over the Semmering Pass into the Mur and Mürz valleys and subsequently to the large inner-Alpine ore and salt deposits. In the west, Limesstraße met the road coming from the west gate at today's Schottentor . On the road leading out of the east gate you came back to Limesstraße via Wollzeile and Landstraßer Hauptstraße in the Rennweg (civil town) area. The road through the north gate (via praetoria) crossed the Danube in Leopoldau and from there continued via Vienna- Aspern into the area of free Germania. A road through the river valley of the Vienna connected Vindobona with the settlements in the Vienna Woods and in the Tullnerfeld .

Surname

The name Vindobona (emphasis: Vinˑd o ˑboˑna) can be derived from the Celtic and is a composite of two members, the first member of which is vindo- to Celtic uindo- meaning “ white ” (compare the individual language variants: Breton gwenn , Welsh gwynn and Irish finn ) or the personal name Vindos. The second term, the noun -bona , means “source (river), foundation (settlement / village)” in Celtic. Vindobona can therefore be resolved as Uindo-bona , "white foundation, soil, village or estate". The formerly Roman place names Windisch ( Vindonissa ), Regensburg ( Ratisbona ) and Lillebonne ( Iuliobona ) each contain one of the two elements.

In addition, Vindobona could also be translated as "Gut or Hof des Vindos", since Vindo was a very common personal name among the Celts. In the absence of archaeological evidence of the existence of a Roman settlement before the construction of the Claudian-Neron auxiliary troop fort, the explanation that the Romans took over the place name from a nearby Celtic court or the boyish oppidum on the Leopoldsberg is an obvious choice . Today it is assumed, however, that Vindobona was not borrowed from the Celtic settlement on the Leopoldsberg, but from a Celtic country residence near the legionary camp. On ancient inscriptions, Vindobona is usually abbreviated as VIND or VINDOB.

From classical Latin to the dialect “Romansh” spoken in the Vienna Basin with Celtic elements, Vindobona probably changed over time to Vindovona, Vindovina, Vindomina . The Slavic Videnica, Vidunji, Viden (as it is still called in Czech today) and finally the German Wienne and "Vienna" developed over non-preserved forms in languages that were spoken in the Vienna area during the Great Migration . An etymological connection between the current place name Vienna and the Celtic-Roman Vindobona cannot be proven. However, Wieden , today's 4th district of Vienna, is probably a short form of the Roman place name. The Old High German name Wenia , from which today's Vienna is derived, could, on the other hand, go back to the Celto-Roman name of the Vienna River, Vedunia ("Waldbach"); An intermediate Slavonic form would also be conceivable, but has not yet been adequately documented.

The city and the legionary fort are mentioned in numerous ancient sources:

- The earliest known mention of Vindobona comes from a fragment of an honorary inscription from Rome (late first century).

- Ptolemy mentioned Vindobona in his work Geographike Hyphegesis as Iuliobona or Vilobona , where its geographical location is also specified.

- In the Tabula Peutingeriana , Vindobona was marked by a two-tower vignette as a stage stop on the Limes Road.

- In the Antonini Itinerary they appear as Vindomana / Vindomenia , and Vindobona / Vendobona .

- In the Notitia Dignitatum is Vindomarae / Vindomanae as barracks by two units under the command of Dux listed from Noricum ripense and Pannonia I.

- In Vegetius' war manual Epitoma rei militaris they are referred to as Bendobona .

- They appear as Vindomina / Vendomina in the Ostrogothic chronicler Jordanes .

function

The bank of the Danube between Klosterneuburg and Hainburg was one of the most endangered border sections in the north of the Roman Empire. It was particularly threatened by Elbe Germanic tribes from the north. This was also the reason why another legionary camp was built there a relatively short distance from Carnuntum as its western flank protection. Other tasks of the crew included monitoring and signaling on the Danube Limes, controlling the trade routes, the Danube and the Limes Strait. Vindobona developed into a regional economic, military and cultural center in the course of time, but was overshadowed by neighboring Carnuntum until well into late antiquity .

Research history

The Roman architectural history of Vienna can not only be recognized by the structural remains, but is also evident in today's streets and their names.

The oldest known description of the city of Vienna was written by Gutolf von Heiligenkreuz . Since the camp wall was still largely upright at that time, he referred to it in his Translatio sanctae Delicanae as "... huge and ancient walls of the city of Favianis, which are said to go back to the Romans ...". At the time of Bishop Otto von Freising († 1158), the knowledge of the country's Roman past was primarily taken from the life of Saint Severin , the "apostle of the Norics", which is why they were mistakenly believed to be the remains of the late antique Favianis fort , today Mautern an der Donau, the site of his first monastery foundation in the province of Noricum. This error persisted well into the 19th century. Last doubts could only be finally eliminated by the excavations in Heiligenstadt in 1952/53. The first Roman finds must have been made when the Babenbergerresidenz , the castle at the court and the Schottenkloster were built. They presumably also influenced contemporary performing arts. The oldest equestrian seals of the Babenbergs from the 12th century could have been modeled on motifs on Roman soldiers' grave stones.

13th to 16th centuries

The first references to Roman finds in Vienna date from the 13th century. The chronicler Jans der Enikel also reports in his royal chronicle that Vienna was the ancient Faviana and was already walled. The possibly intentionally wrong equation with Favianis was made by Otto von Freising. Otto staged his brother Heinrich II. Jasomirgott (since 1156 Duke of Austria) as a prince over the Noriker. It is noticeable that Heinrich decided to reside in Vienna almost at the same time, so that one can assume that the incorrect Favianis-Vienna identification served as an “ideological impetus” for the city's upswing. The “Perchhof” ( Berghof ) is also mentioned in the Prince's Book of Jans Enikel . Since numerous ancient legacies later came to light at its location, Paul Uiblein did not consider it impossible that Roman masonry was also used or included in the construction of the building and that this also encouraged the creation of the legend about Vienna's supposedly oldest building. In 1277, Bishop Konrad von Freising gave a master Heinrich a ramshackle stone house from extremitate muri next to the old tower, which was destroyed by fire and stretched from east to west as far as the St. George's Chapel. This chapel belonged to the former so-called Freisinger Hof (today Trattnerhof / Graben) since 1468, 47 which can still be localized through some historical plans. This old tower was associated with findings in Goldschmiedgasse 5–7 by Friedrich Kenner and viewed by him as a remnant of the camp fortifications. Gutolf von Heiligenkreuz writes in his Translatio Sanctae Delicianae from the 2nd half of the 13th century that Roman walls were still upright. The first attempts at scientific research into Roman Vienna go back to the 15th century. The theologian Thomas Ebendorfer von Haselbach once again mentioned the Berghof as the oldest building in Vienna in his Chronica Austrie and assumed that the city was founded under Gaius Iulius Caesar . At the end of the 15th century, however, little attention was paid to Roman ground monuments. The focus was solely on unraveling the ancient name of the place and on collecting inscriptions, two of which were found in 1493 on Wipplingerstraße and one was placed in front of the University of Vienna . In the second quarter of the 16th century, the personal physician of the Viennese imperial court, Wolfgang Lazius , systematically collected reports on Roman artefacts in Vienna and Roman antiquities and inscriptions, published them and exhibited some of them in his house, the Lazenhof at the farmers' market . Except for five copies, they were lost again. Another collection of inscriptions goes back to the fortress builder Hermes Schallauczer , who was able to recover six ancient inscription stones between 1553 and 1559 during repair and reinforcement work on the Vienna city wall. With the end of the Renaissance , however, scholars lost interest in Vienna's Roman past.

18th and 19th centuries

Between the end of the 17th and the middle of the 18th century, two Roman sarcophagi, a coin hoard and a fragment of a list of names of the Legio X were recovered. Around 1800 ancient building remains and graves were discovered in the construction of the Neustädter Canal in the 3rd district. Most of the found items were sold immediately to private collectors. In the middle of the 19th century, Anton von Steinbüchel devoted himself again to researching Roman inscriptions from Vienna. Find descriptions were published by Adolf Schmidl between 1844 and 1848 in the Austrian papers for literature and art . From 1849 to 1867, Johann Gabriel Seidl also published reports on finds in his archive for customers of Austrian historical sources . In the second half of the 19th century, urban archeology experienced a new upswing with the demolition of the city fortifications. In 1865, under the direction of Friedrich von Kenner from the kk Münz- und Antikenkabinett, the documentation of the findings was carried out according to strictly scientific methods, a systematic recording of the stone monuments and the search for the exact location of the legionary camp. He was supported in this by Josef Hilarius Nowalski de Lilia , who organized an archaeological find news service, with the help of which he was able to seamlessly monitor the numerous construction sites in the inner city of Vienna and immediately secure ancient finds. The late antique graves in particular were meticulously documented in the 19th century. In the area of the canabae legionis , too, for a long time the interest was not focused on the settlement findings, but exclusively on the burial grounds.

20th and 21st centuries

In 1901 the City of Vienna founded a “Municipal Council Committee for the Promotion of Archaeological Research in Vienna”. At his instigation, the Roman Museum of the City of Vienna was established in 1903 . Nowalski de Lilia was appointed its first director. Wilhelm Kubitschek and Emil Polaschek ( Roman Museum Vienna ) directed the excavations in Wipplingerstraße and on Hohen Markt . Polaschek was primarily concerned with researching the layout of the camp. Favored by the increased construction activity at the turn of the century, more and more remains of the legionary camp came to light, for example. B. the west gate at the high bridge (1900-1903). The course of the southern wall could also be traced for the first time from the former southwest corner of today's Naglergasse to the ditch . Kubitschek finally succeeded in his exact localization and also that of the civil town in the 3rd district. From 1946 the research work was continued by Alfred Neumann , employee of the Historical Museum of the City of Vienna . While working to repair the war damage, he succeeded in salvaging further valuable finds and in the archaeological clarification of important historical connections. We owe Neumann numerous detailed knowledge of the legionary camp. During the reconstruction work in the city center, building remains of the interior of the camp such as B. found that of a thermal bath on Hohen Markt. During the construction work, mainly large quantities of ceramic shards and small finds were recovered. Neumann also initiated the establishment of the archaeological showrooms at Hohen Markt and Am Hof . His office was later taken over by Ortof Harl, who reorganized Vienna's urban archeology. Further research results were obtained primarily during the construction of the Vienna underground from the 1970s, during excavations at Wildpretmarkt (in 1980, during the identification of the barracks of the 1st cohort and floor plan reconstructions in comparison with old excavations), at Michaelerplatz, on the Freyung and won in Unterlaa ( Johanneskirche ). The excavation between 1989 and 1990 at Rennweg No. 44 yielded further findings from buildings and workshops. During the excavations at Michaelerplatz in 1990/91 and on the Freyung between 1992 and 1994, as well as on the Neuer Markt , the building structures of the canabae could be examined in more detail and the chronology of the settlement determined. The excavations between 1995 and 1998 at Judenplatz again produced a wealth of new information.

Between 1994 and 2000 they dug again on the area of the civil town. It was found that the pointed trenches found there could not have come from a military camp. The Viennese urban archeology recorded the sites in a database until 1998 and processed the old excavations. From 2000 to 2011 settlement findings, streets, graves, ovens and part of the fortifications of the civil town could be uncovered. From the end of 2012 to the beginning of 2013, Vienna City Archeology carried out excavations again in Steinergasse and Geblergasse on the site of the former legionary brickworks. Two well-preserved brick kilns standing next to each other could be examined. In particular, the emergency excavations in the course of new buildings lead to new insights into Vienna in Roman times.

In May 2019, again during an emergency excavation, the foundation stones of the Porta Decumana, the south gate, were archaeologically confirmed for the first time, making its exact localization possible. The foundation is on the corner of Naglergasse and Tuchlauben.

While working on his dissertation, the historian Niklas Rafetseder discovered the importance of a bronze plaque that had been in the depot of the Wien Museum for almost 100 years . He managed to decipher the true meaning of this inconspicuous piece of metal - the fragment was part of a city law plaque. Thus the Roman Vindobona had the town charter ( Municipium ) about 1000 years before that , long before medieval Vienna (since 1221).

development

Pre-Roman times

The Vienna Basin was already a popular settlement ground in pre-Roman times. Finds of the Neolithic Danube culture in the Vienna Prater date from around 3000 BC. The mainly arable population ( Illyrians , Boier , Eastern Alpine Celts ) lived in small, scattered villages. The Celts migrated in the 4th century BC. In the Vienna basin. During this time, a fortified Boier oppidum was probably built on the Leopoldsberg . It is unknown whether Celtic settlements were already established in the plain around the future Roman settlement site at this time, but it is very likely due to the fertile soil. Findings from the late La Tène period in Ungargasse as well as traces of wooden structures in the area of the legionary camp and in Klimschgasse near the Rudolfsspital indicate this. A buoy settlement is suspected on the city terrace east of the Wien River, in today's 3rd district (ceramic finds).

1st century

In the second half of the 1st century BC BC Dacians and Boiers penetrated from the east into the regnum Noricum . To protect him, the Romans, allied with the Noriks, had to repeatedly deploy troop contingents. After a large-scale raid by Noriks and Pannoniern to Istria , Augustus subjugated 16/15 BC. Also the eastern Alpine peoples and occupied their settlement areas up to the Danube. During this campaign the Roman army also reached Vindobona . Here they found an extraordinarily favorable settlement area, a glacial terrace landscape that was surrounded by watercourses. Around 15 BC The Kingdom of Noricum was incorporated into the Roman Empire and the Danube became the new frontier. Probably around the year 14 the Vienna Basin was also incorporated into the province of Pannonia. Until the arrival of the Romans, the region was still ruled by the oppidum on the Leopoldsberg. It may also have been the eponymous settlement for the later legionary site. Otherwise only little is known about it, above ground only its walls can still be recognized by means of slight elevations in the terrain.

The finds indicate the establishment of a first Roman base in the Claudian - Neronian times. Presumably it was just a smaller, makeshift camp, perhaps an outpost of the Carnuntum legionary camp . During the excavations at Hohen Markt, various wooden constructions and finds from the 1st century were examined, which Hertha Ladenbauer-Orel interpreted as the remains of a fort. During the reign of Nero and Galbas (54 to 69) it was expanded a little further. Bricks from the imperial brickworks Pansiana , which had been fired in Aquileia , were also found here. This leads to the conclusion that the region around Vindobona was not very well developed at that time, as even the bricks had to be brought in from northern Italy. Small amounts of found northern Italian vessel fragments that were produced from the Claudian era also support this assumption. At the same time, a large part of these shards - plates with appliqués - are evidence of the presence of Roman auxiliary troops in the 1st century AD.Other ceramic finds, this time from the reign of the Flavians , suggest that a trading center must have existed there at that time .

In order to better control the Celtic population, the Romans had all oppida forcibly evacuated and destroyed after the consolidation of their rule . Most of its residents were settled in Vindobona . The rest of the indigenous population withdrew to the valleys of the Vienna Woods. After 41 the systematic expansion of the Danube Limes began. The route of the Limes Road was probably planned at the time of Tiberius and laid out by the Legio XV. From then on, at least the section on Vienna's city terrace must have existed. Watchtowers were built on the western edge of the Vienna basin. From the Nussberg you had z. B. Visual contact to the Pfaffenberg near Carnuntum . From these heights the hinterland between Vindobona and Carnuntum was easy to see. From the late 1st century AD, Vindobona developed into a legionary fort with a prosperous military and civil town ( Canabae Legionis or Municipium ) . The former was probably built during the reign of Domitian or Trajan , who died in 98 C.E. a. also stayed in Pannonia. During this time, the Limes road to Carnuntum was also expanded.

2nd century

At this time, the northern borders of the empire were largely quiet, as Rome had concluded alliance agreements with most of the neighboring Germanic tribes. The long period of peace ( pax romana ) enabled the camp and civil town to expand steadily. On the left bank of the Danube, among other things, a Germanic settlement with a trading center can be identified from the 2nd century. Between 103/104 the province was divided into Upper and Lower Pannonia. Vindobona was now in the area of the province of Upper Pannonia (Pannonia Superior) . In Upper Pannonia itself, Roman rule was so firmly established that vexillations of the Legio X Gemina to suppress the Bar Kochba uprising (132–135) in Judea and for use in the war against the Moors under Antoninus Pius in North Africa could be withdrawn (145-152).

Over the course of time, the settlement area expanded further south to the river valleys of the Wien and Liesing . Aqueducts, temples and burial grounds were created. Civilians and legionary soldiers were supplied with food from Roman manors ( Villae rusticae ) in the area, one of which was discovered in Unterlaa (see below). In addition to military facilities such as B. Quarries ( Sievering ), brickworks ( Hernals ) arose around Vindobona and some settlements founded by veterans (Inzersdorf). In the period between Hadrian and Antoninus Pius , Vindobona reached its peak. At that time, there around 30,000 people may have lived, the native Celts and the Romans immigrated mingled and went in new people in the second and third generation novels on.

From 166 to 169, the introduction of the Antonine plague and the overcoming of the Limes by Marcomanni and Quadromas under their army king Ballomar between Carnuntum and Vindobona ended the Golden Age of the Roman Empire ( First Marcomann War ). Legion camp, camp city and civil city were largely devastated. It has not yet been clarified whether the legionary fort was captured by the invaders or evacuated and set on fire by the garrison to make it unusable for the enemy. Coin hoards prove that the civilian population also suffered great losses. It is likely that Roman rule in the Vienna Basin collapsed completely at that time. Between 170 and 178, after lengthy fighting, Marcus Aurelius succeeded in pacifying Pannonia again, and Vindobona was reoccupied by the Roman army. As a next step, Rome planned to occupy the settlement areas of the attackers north of the Danube and to incorporate them into the empire as the new province of Markomannia . This did not happen, however, because as early as 177 the marcomanni invaded Pannonia again ( second marcomann war ). A counter-attack probably came from Vindobona , as two large temporary camps north of the Danube, Stillfried an der March and Charvátská Nová Ves, are located directly on the advance route from the Viennese legion camp. The historian Aurelius Victor reported that the office tired emperor, there probably during the Marcomanni wars had one of his headquarters, after March 17 180 "in Vendobonae" at the plague died, but his actual place of death should the city Sirmium been on the lower Danube be.

The battles of the Second Marcomann War had no direct impact on the region around Vienna and the reconstruction could therefore begin relatively undisturbed. In 193, the governor Septimius Severus , who resided in Carnuntum , came to the imperial throne with the help of the powerful Danube Army, which resulted in a renewed economic upswing for the Pannonian Limes regions and also for Vindobona . Since the Pannonian legions had given him particularly active support in his accession to the throne, he owed special thanks to these provinces.

In 1913, during excavations at Am Hof, a fragment of an inscribed bronze plaque was found. Based on comparisons with other such texts, the town charter of Vindobona, the existence of which is considered controversial, could have been written on it. The tablet is roughly dated to the period between AD 120 and 250.

3rd century

After the stabilization of the political and military conditions, numerous new settlers soon streamed into the Upper Pannonian province and accelerated the reconstruction. From the early 3rd century onwards, the finds of Germanic burials increased; The presence of a huge imperial army also greatly promoted Vindobona's economic recovery . During an inspection trip by Severus between the years 202 and 212 or under his successor Caracalla , the civil city was declared an autonomous city of the second order ( Municipium ) and thus also slightly upgraded compared to the provincial capital Carnuntum , which had recently received the title of Colonia . At the same time the Limes road was repaired by the Legio X between Vindobona and Carnuntum .

The city's rebloom ended in the second half of the 3rd century. First, a flood of the Danube caused large parts of the north-western camp area to slide down due to undercutting, and some buildings in the western suburbs also fell victim to this. Subsequent incursions by the Marcomanni, Quadi, Alamanni , Sarmatians and Vandals (258–260 and 270–283) once again led to severe devastation throughout the province. Whether Vindobona was also affected could not be confirmed archaeologically. Finally, under Diocletian , Upper Pannonia was divided into two new provinces around 293, Pannonia I and Savia . Vindobona was now part of Pannonia I.

4th century

The military reforms Diocletian and Constantine I (3rd to 4th century) reduced gradually, the strength of the team Legio X . The areas in the fort that became free were taken over by the population as living and working places after the destruction of the camp and civil town. The legionary fort was transformed into a kind of fortress town ( oppidum ) with a military garrison. The largely devastated suburbs have been almost completely abandoned and largely leveled. The demolition material was used to repair the camp wall and to build additional defenses. New burial grounds were created along the arterial roads. Between 320 and 325 Vindobona became a bishopric, the incumbent also represented his congregation at the Council of Nicaea . In 342 Emperor Constans visited Pannonia and probably also passed Vindobona . Under Valentinian I (364–375) the Pannonian Limes was reinforced again. He should have been the last Roman emperor who stayed in Vindobona .

In 375 or 378 the Sarmatians burned down the neighboring Carnuntum , whereupon the headquarters of the Danube fleet , classis Histrica , had to be relocated to Vindobona . After the catastrophic defeat of the Eastern Roman army against the Greuthungen and Alans near Adrianople in 378, Huns and Germanic tribes immigrated to Pannonia and were settled there as federates . These events were also reflected in the finds from the camp and the burial grounds of Vindobona . According to the Notitia dignitatum , Marcomannic federates, among other things, were stationed in the Pannonia Prima , who were commanded by a tribune ( tribunus gentis Marcomannorum ). He probably set up his residence on the Oberleiser Berg . With the advance of the Huns under Attila to the west, the migration of peoples reached its first climax, the effects of which also left clear traces in Vindobona . During this time, most of the military settlements on the central Danube went under, which could also be related to another invasion of the Marcomanni around 395.

5th century

As has been observed several times at Norian and Pannonian fort sites, the final decline of Roman culture and Roman settlement activity also began in Vindobona at the beginning of the 5th century. In 401 the Vandals crossed the Limes. After that, between 405 and 406, the Ostrogoths under Radageis devastated the former legionary camp on their way to Italy, but it was apparently partially rebuilt. A coin hoard at the meat market was hidden around 408 ( final coin ), probably at the time of the end of Roman rule over Vindobona . In 433, Emperor Theodosius II ceded western Pannonia to the Huns by means of a federal treaty. At that time Vindobona was probably mostly in ruins. In the second half of the 5th century, most of the traces of building on the floor of the legionary camp break off. The end of the legionary camp could be clearly seen on the collapsed roofs of the barracks. Above them lay a layer in which no more new buildings could be detected, but isolated finds from late antiquity could still be recovered. Above it lay an empty layer, which led over to the high medieval find horizons without any recognizable transition. Only the area around the Ruprechtskirche could be considered for further settlement during the “Dark Ages”, but so far there has been no opportunity for a new scientific excavation.

In previous archaeological excavations, however, it could be clearly proven that in the eastern corner of the legionary camp, today the area around the Ruprechtskirche , the settlement was not affected by the manifold upheavals at the beginning of the 5th century. There the traces of an early medieval settlement in Vienna were clearly visible. This finding also fits in with the discovery of Longobard graves in Salvatorgasse (6th century). It is also supported by the information given by Jans Enikel about the importance of the Berghof in ancient times. Added to this is the particularly protected location of this section (the highest point of the former legionary camp) and the founding of the Ruprechtskirche in Carolingian times.

According to legend, the city was also the scene of an episode of the Nibelungenlied . After Siegfried's violent death , Kriemhild traveled with a large retinue along the Danube to the land of the Huns ( Pannonia ) to marry their king. Etzel went halfway towards her and the wedding celebrations were held in Vindobona . 453 the settled Rugier in the surrounding areas. After the end of the Hun Empire initiated by the East Germanic Gepids in the course of the Battle of the Nedao , the Western Roman Emperor Avitus (455–456) tried in autumn 455 to win back Pannonia, which had long been a bone of contention between Ravenna and Constantinople . The rule of West Rome over the province seems to have officially ended at this time, because it was the Eastern Roman Emperor Markian (450–457) who allowed the Ostrogoths to settle on the land between Sirmium and Vindobona. In 473 the military leader Odoacer took control of the heartland of the Western Roman Empire, Italy, and deposed the emperor in Ravenna. The legionary camp had probably been gradually abandoned by its residents - by the middle of the 5th century at the latest. A large part of the Romansh ethnic group migrated to Italy after the destruction of the Rugier Empire around 488 by order of the Odoacer. Grave finds near the legionary camp indicate the presence of East Germanic and Hunnic federates at this time.

Early middle ages

Early Vienna evidently developed within the Roman camp walls, which lost its military function in the 5th century. The settlement activity ceased at the latest by the middle of the 5th century within the camp area. Settlement continuity, which was still believed to be secure in research in the 1970s, is hardly mentioned today. The Vienna Basin was then alternately ruled by Goths , Lombards and Avars . As in neighboring Carnuntum , new settlers (possibly Herulers ) settled there again after the passage of various armies , who took the building material for their dwellings from the ruins of the Roman city or the legionary camp. They holed up in the former camp bath and erected a temporary fortification there, from which a castle complex and subsequently the Berghof emerged . In the north-east of the camp area ( Fischerstiege -Fleischmarkt- Fischhof ), which had served as a refuge during the migration period, a marketplace was established that secured the livelihood of the new residents. The area around today's Peterskirche was also still inhabited. It could go back to an ancient predecessor building, but as a church - despite the Lazius legend of its founding by Charlemagne - it must be dated to the 11th century. The settlement around St. Peter had heap village-like features and should have been inhabited from the 5th to the 8th century. In any case, in comparison with the settlement areas around Berghof and St. Ruprecht, its chronology is more likely to be limited to the end of this period, i.e. to the Carolingian era (around or after 800).

In 489 the Lombards reached the middle Danube and settled north of the river. In 511 they shook off the Herulian supremacy under their king Tato and also occupied Vindobona . Their grave goods, Byzantine copper coins from the 6th century, suggest lively trade contacts with the East. During the excavations in Salvatorgasse, other graves from this period were uncovered. In 568 the Lombards also withdrew to Italy. No further traces of settlement could be observed until around 600. Some ceramic finds from the building rubble of the Berghof indicate at least an inspection of the camp ruins in the 8th and 9th centuries. In Vindobona now ruled until their subjugation by Charlemagne the Avars. The small fortifications in the camp bath existed until the 8th century, after which there was no evidence of any settlement activity until the 12th century. Between 791 and 796, West Pannonia was finally incorporated into the ambitious Frankish Empire as part of the Avar Mark and colonized by the Bavarians . However, the chances of a gradual consolidation and upswing of the remaining settlement dwindled again in the second half of the 9th century, as the Magyars overran the Vienna area. The name Vienna was mentioned in a document for the first time since late antiquity. The mention of apud Wenia in the Annales Juvavenses maximi of 881 in connection with a battle against the Magyars suggests that the place was never completely abandoned or abandoned. Ruprechtsplatz, where settlement remains and finds from the 9th and 10th centuries piled up, was regarded as one of the nucleus of the medieval city. But settlement activities were also likely to have started outside of the former legionary camp during this time. Excavations in St. Stephen's Cathedral revealed traces of burials from the 9th and 10th centuries. This would make the thesis of only assuming a single settlement core obsolete. In addition, a tower-like structure was uncovered there, which is older than today's St. Stephen's Church. Some of the ruins were still used as burial places.

Outpost

During excavations at the Herrengasse- Freung intersection , the remains of a small wood-earth fortification were found. Presumably it was an outpost of the legionary camp in Carnuntum , from which either a division of Legio XV or an auxiliary cohort of around 100 men monitored the ford across the Danube. It was located near Limesstrasse, and it may also have housed a building vexillation that was in charge of building the road.

Alenkastell

The equestrian fort, possibly 4.29 hectares in size, was located in what is now the 1st district of Vienna and was probably built between 85 and 100 years ago. It could have been founded before the legionary camp, during or shortly after Domitian's campaign against the Quaden , Marcomanni and Iazygen , between 91 and 92 AD, a little northeast of the Limes road. In the Harrach Palace, the remains of a wooden building from the 1st century, which was regarded as a barracks block, were excavated. In 1995, during construction work in a basement under the inner courtyard of the Schottenstift, proof of an 8.3 m wide pointed ditch, possibly the fort ditch, was found. Perhaps a section of the Limes Road served as the via principalis of the camp. The burial ground of his first occupation unit, the Ala I Britannica , was found in the area of Stallburggasse, only 600 m away from where the Spitzgraben was found. The vicus of the camp could have extended from Am Hof over Freyung to Michaelerplatz. The latest excavations carried out in the Freyung-Schottenkloster-Harrachpalais-Porciapalais area have shown that it actually stood there, the main axis of which was probably the Schottengasse-Herrengasse street.

Legion camp

The approx. 18 to 18.5 hectare legionary camp was probably built around 97 AD in what is now the 1st district of Vienna on a tributary of the Danube using stone construction. The fortress offered space for approx. 6000 soldiers and, when fully expanded, covered an area of approximately 400 m × 500 m. Its narrow side was oriented towards the Danube. Due to the terrain, the northern part ran diagonally along the edge of the abortion that was created in the 3rd century (today Am Gestade ) of the camp plateau facing the Danube bank. The original legionary camp must originally have had the classic rectangular floor plan with rounded corners (playing card shape). Otherwise the area of the principia would have been the largest in the entire Roman Limes. A camp constructed in this way could not have provided enough space for 6,000 soldiers. The axis cross of the camp must have been in the area of the Jordangasse, the west-east axis was formed by the via principalis , which ran between the Wipplingerstrasse and in the Ertlgasse. A system of ditches was in front of the camp as an obstacle to the approach. As expected, the gate systems could be located in the west, south and east.

An inscription from the Legio X and a fragment of the monumental building inscription on the east gate are considered to be the oldest epigraphic evidence of the legionary camp. The inner buildings are likely to have been built in stone from the start. The findings at Judenplatz, however, showed that the barracks were still largely made of wood. There was little evidence of building activity in the 2nd century. During the Marcomann Wars, the camp was almost completely destroyed by fire. The reconstruction was carried out under Marcus Aurelius, with walls that can still be used being incorporated into the new buildings. The new warehouse obviously hardly differed from its predecessor.

The excavations at Judenplatz have shown that the camp was completely rebuilt or restored in places in late antiquity. Sections of the earlier fortifications and interior structures that had been better preserved were reused. The flank tower of the west gate is a particularly good example. Its square floor plan still corresponded to the gate towers of the late Flavian camps, there were no indications that it was no longer used in the late Roman period. Spolia such as B. Gravestones, reliefs and architectural fragments from early and mid-imperial times were built into the late Roman fortifications as a welcome addition to the building material after the chaos of war and the natural disaster in the second half of the 3rd century. This procedure could be observed at all archaeologically examined points of the camp.

From the 3rd century onwards, some buildings were given up or downsized as a result of troop withdrawals. During this time there was also evidence of a flood event, which in the northern part - due to a landslide - fell victim to almost a third of the camp area. In the middle of the 4th century the camp was again badly damaged, probably by an earthquake. The east wall, which was obviously badly damaged, was quickly rebuilt or repaired. For this repair work, spolia such as B. used tombstones from the surrounding burial grounds. The fort wall was later reinforced by adding new towers. The last construction phase of the legionary camp fell in the first half of the 5th century. Simple half-timbered or wooden buildings on foundations made of rubble stones without mortar bonding and with hastily poured screed floors were set over the previous parcel structure. They were no longer oriented towards the camp axes and had nothing in common with the previous Roman military building scheme. The now mostly civilian residents of the camp redesigned some usable buildings from earlier construction phases into smaller residential units. A late antique burgus or a remnant fort in one of the corners of the camp to accommodate the remaining crew has not yet been archaeologically proven.

The layout of the warehouse can still be seen from the course of the following streets:

- Graben : The name is said to go back to the fortification ditches of the Roman camp; Whether the Möhringbach, which no longer exists today, but which flowed east of the camp area until modern times, was an artificially created sewer in Roman times has not been completely clarified.

- Naglergasse: When the house front bends to the north, the south-western corner tower of the camp is assumed, in the southern side streets the system of ditches in the area is also visible.

- Tiefer Graben : Western end of the camp fortification, the deeply incised, presumably naturally formed, brook bed of the Ottakring brook, which has been visible up to modern times.

- Rabensteig,

- Rotenturmstrasse ,

- Salzgries: The sloping part in the area of the Salzgries was created by the underwashing and sliding of the northwest corner in the 3rd century. The effects of this catastrophe can still be clearly seen at the edge of the Ruprechtskirche or Ruprechtsstiege and at the Maria am Gestade church.

Storage wall

The fort wall was three meters thick and consisted of rubble stones that had been piled up like a herringbone. On the outside it was faced with humpback blocks and crenellated in the upper area. The southern section was the most solidly fortified part of the defensive wall from the start, as there were no natural obstacles to approach. It was considerably strengthened again in late antiquity. The exact course of the north wall in the 1st and 2nd centuries is in places unknown. After the impact slope of the Danube at the north-west corner of the camp had been submerged and slipped , the northern section of the wall had to be almost completely rebuilt or adapted to the course of the demolition edge. For this purpose, additional support pillars were erected on the bank line for stabilization. For the late Roman Vindomarae, with its already greatly reduced crew, a storage area of the earlier dimensions was no longer necessary. The effects of this natural disaster were still clearly visible in the drilling profiles from Gonzagagasse, the western section of which roughly coincides with the course of the northern camp wall. Some of the drilling profiles indicated the presence of wall remnants or debris deposits made of stone, brick and ceramic material far below the alluvial layers of the Danube. Even at a depth of twelve meters, excellently preserved palisade wood was found. An altar stone of the river god Acaunus (the personification of the Vienna River) found in the Vorderen Zollamtsstraße 5-9 / Marxerbrücke in 1899 was perhaps donated in connection with this flood event. Large parts of the fort wall stood upright well into the Middle Ages, as reported by the chronicler Gutolf von Heiligenkreuz in the 13th century . Especially in the west and south, the wall and gates were still well preserved, as can be seen from today's streets.

With the appointment of the Babenbergs as dukes of Austria (privilege minus) in September 1156, Heinrich II. Jasomirgott may have expanded Vienna into his residence, using the Bavarian Regensburg as a model. He had a castle built in the SW corner of the former legion camp (Am Hof). In addition, Heinrich founded the Schottenkloster in front of the medieval city wall, which followed the course of the legionary camp. Only the east wall, which was already too badly damaged, was torn down. The warehouse area soon became too small due to the rapid expansion of the city. The previous building of St. Stephen's Cathedral (from 1137) had to be built outside the walls. As a result of the first major city expansion under Duke Leopold V around 1200 (financed with the ransom for the release of the English King Richard the Lionheart ), the camp wall was then completely torn down. The monastery area was only after the city expansion at the latest under Leopold VI. (1198–1230) enclosed by the new city fortifications, which now included a much larger area. The knowledge and use of the fortified area of the former camp during this time are evidence of the adaptation work on Roman walls and the camp baths. The Roman ruins were probably used to extract the building material for the buildings erected in the Middle Ages, but on the other hand they were partly used as foundations (excavations on Judenplatz, in the courtyard of the Tuchlauben 17 and Am Hof). The resulting stone material, which also contained numerous spolia from the Middle Imperial period, was used to fill the Roman moat or for other building projects (e.g. St. Stephen's Cathedral).

Trench system and approach obstacles

The southern and eastern glacis of the legionary camp was additionally protected by a 55 m to 60 m wide "death zone" with various obstacles to approach. The bench directly in front of the camp wall was about 60 cm wide. One embankment fell steeply to a total of three parallel, 6.5 m deep pointed trenches. In front of the trenches there was a guard path, which was covered by a palisade . This was followed by a road that probably ran around the whole camp. It was replaced by an 18 m wide safety strip, which was peppered with irregularly laid out 1.2 m × 4.5 m trap pits. The southern camp ditch was used until the 12th century.

Towers and gates

The wall was reinforced with internal square towers. On the west, north and east walls none or only a few of these towers could be archaeologically proven. At courtyard no. 9 (new fire brigade headquarters), the remains of a 2.90 m × 1.90 m intermediate tower of the western wall and the inner earth ramp (battlement) came to light at a depth of 3 m. Three copies of the southern wall were located along Naglergasse. The discovery of half-column fragments ( pilasters ), cornices ( Kärntner Straße ), monumental building inscriptions and Corinthian column capitals ( Ertlgasse ) suggests that the gates were decorated with a triumphal-arch-like blind facade .

The location of three of the four gate systems is each secured by an excavated flank tower.

- North gate (porta praetoria)

- Its location is still unknown. Possibly it was just a small slip gate to the port area, which was in the area of the Maria am Gestade church .

- South gate (porta decumana)

- The western flank tower and a small remainder of the eastern specimen could be located in the Naglergasse-Tuchlauben area in 1902. The core substance of the gate, which perhaps existed until the 12th century, is said to have been preserved in the Peiler or Bairertor . Remnants of the foundations of a tower-like building, which were found during the renovation of Bognergasse, originated from Roman times. The Peilertor stood on the corner of Tuchlauben- Bognergasse and was removed in 1760 because it impeded the steadily growing through traffic. In 2019, massive stone blocks were found in the Graben / Tuchlauben area, which were uncovered during excavations after a gas breakdown; they were part of the foundation of the Roman gate. Thanks to this discovery, it could now be located fairly precisely. Just a few meters away, another cuboid was uncovered that marked the central pillar ( spina ) of the gate. Remnants of gravel from the ancient road surface, which was much more durable than that which was applied in the late Middle Ages, could also be observed.

- West gate (porta principalis sinistra)

- The gate system was located at Hohen Brücke / Wipplingerstraße No. 21. Until 1900 it was thought to be in the area around the medieval Ungartor (Lichtensteg-Rotgasse). The northern flank tower, which was archaeologically proven when the Art Nouveau bridge was built in 1903, stood at the Hohe Brücke. At the Tiefen Graben, tower foundations were found that were about 2.50 m wide. The gate system was originally approx. 20 m high and could be passed through two passages. A sewer ran under a passage. During the excavations, components of the tower such as B. recovered a pan stone with mortise, fragments of the arches, roof tiles and a profiled foundation plinth. The latter suggests that the tower walls were divided by pilasters. There was no artificial trench system in front of the gate, it was adequately protected by the steeply sloping bed of the Ottakringer Bach.

- East gate (porta principalis dextra)

- The gate system was in the Kramergasse-Ertlgasse area. By mirroring the left flank tower of the west gate, the position of the right flank tower could be identified (location: Krammergasse 9 or Bauernmarkt 14). In the Kramergasse-Ertlgasse canal excavations in the middle of the 19th century, remains of the gate wall 2.26 m high, 2.5 m wide and 10.1 m long came to light. There were a total of four wall sections that stood parallel to each other (walls A, B, C, D), the space between them was 5.6 m wide. The rising masonry consisted of mortared rubble stones ( Opus spicatum ). The gate could be passed through two passages. Two sewers were found under the gateway. In 1971, Alfred Neumann cut the peat foundations again during an excavation in Ertlgasse. The front of the flank tower in Kramergasse was pulled slightly in front of the camp wall during later renovations (end of the 2nd century?). The 24 brick stamps found in the area of the gate all come from the Legio XIII . Some architectural fragments could also be recovered from the former moat (Kramergasse area). In 1896 a fragment of a building inscription with the letters “NERV” was found in Rotgasse, which was probably once attached to the gate.

Interior development

The interior of the camp corresponded to the usual scheme for such Limes fortifications. The east-west running main road (via principalis) separated the fenced area into a smaller north half (praetentura) and a slightly larger south half (retentura) .

The exploration of this area of the camp was always dependent on chance finds in limited excavation zones due to the strong modern buildings. Just enough is known of the interior structures to be able to roughly sketch the floor plan of the camp. The excavation of the side canal of the via principalis in 1937 proved that the camp buildings had been laid out in a rectangular grid. Above all, the principia (commandant's office) and the praetorium (house of the camp commandant) as well as the via principalis (west-east main road of the camp) could be determined exactly. From late antiquity, more and more findings and finds in a civilian context can be seen inside the camp (handicrafts, bangles made of glass and ivory, burials of newborns); this is probably the partial withdrawal of Legio X due. Also on the area of the team barracks (Judenplatz) there were clear changes in the building structures, the remains of workshops and ovens also point to a later civil use. The buildings of the late phase of the camp in the 5th century were only erected using simple drywall technology.

Barracks

Remnants of the barracks were cut into at Am Hof, Judenplatz , Ruprechtsplatz and Wildpretmarkt. The first St. Peter's Church was the oldest church building in Vienna. It was built in the second half of the 4th century and stood on the walls of a barracks building on which a single-nave hall church ( basilica ) was built.

At the Wildpretmarkt it was possible for the first time to capture the full extent of one of the quarters of the 1st cohort . It was a long, rectangular, one-story, 60 m × 35 m double barracks with a 7.5 m wide central aisle. Up to 80 soldiers (centuria) could be accommodated in the team barracks, which were mostly built in half-timbered construction . They were organized in shared apartments for eight people (contubernia) . These were in turn divided into three rooms, living and sleeping areas, cooking area ( papilio ) and weapons room ( arma ). Like the main buildings of the camp, the accommodations of the 1st cohort were built in stone in their first phase.

During the construction of the Holocaust memorial at Judenplatz, four crew barracks with gravel roads and paths in between were archaeologically examined on an area of 250 m². Two barracks stood facing each other with the entrances and had a portico made of wooden posts. The foundations of five residential units, each with a living room and a weapons room, were still preserved for each building. They were attached directly to the centurion quarters. The building history of the barracks is divided into a total of six periods (including two wooden construction periods). The buildings were initially only made of wood. In between ran a gravel road with drainage channels on both sides. In the second half of the 2nd century, the outer walls of the barracks were made of adobe or adobe framework. The 1 m high foundations and load-bearing inner walls were built from rubble stones and mortar . Unburned clay bricks were used to raise the dividing walls . The floors were made of clay or mortar screed . The centurions lived in larger quarters that were attached to each barracks as so-called head buildings.

Research in the canabae or burial grounds indicates that from the 4th century onwards, part of the storage area was given over to the civilian population. This was mainly made possible by the gradual reduction of the Legion's manpower. Typical military buildings could still be seen at Judenplatz, but these contubernia were less likely to have been intended to accommodate soldiers than as workshops. These buildings stood until the first half of the 4th century. At the latest in the reign of Valentinian I (364-375) they were destroyed. Then the workshops mentioned were built on their foundations, some of their rooms were equipped with simple hose heating. At the end of the 4th century, however, the barracks on Judenplatz were completely derelict. For the late 4th century there were major restructuring measures on the site of the former barracks. Masonry that was still usable was still used, but the floor plans changed fundamentally. Additional living spaces were created by drawing in new intermediate walls. In late Roman times they were mostly built on a layer of broken roof tiles from the Middle Imperial period. The late antique findings of the 4th and 5th centuries suggest that these buildings were erected in great haste and with the simplest of means. For the most part, demolition material from earlier eras was used, which apparently was preferred as building material. For what purpose these buildings were used could not be clearly clarified.

Principia

The administration and command building was a little south of the via principalis and thus almost exactly in the center of the camp area. It had an almost square floor plan, probably 70 m × 90 m, and could be entered through the main entrance in the south. Its rooms are grouped around two paved inner courtyards ( forum ). In the north wing there was the armory ( armamentaria ), a meeting and parade hall ( basilica ) and the flag sanctuary ( aedes ). The administration rooms of the camp administration ( officia ) were located on the southern, western and eastern sides of the inner courtyard . Its facades were the only known buildings in the camp to be decorated with reliefs.

Praetorium (Legate Palace)

The quarters of the camp commandant ( legatus legionis) were probably northwest of the Principia . Some high-quality remains of wall painting and stucco fragments that may have come from this building were discovered in the eastern part of Judenplatz.

Officers quarters

The representative buildings of the staff officers (so-called tribune houses), built in the Greco-Roman style, stood behind the eastern camp gate, at today's Hohen Markt , directly on the northern edge of via Principalis and covered an area of approx. 3500 m². They are among the best-researched buildings in the legionary camp. The row of houses (scamnum tribunorum) measured 40 m × 50 m and originally consisted of six multi-phase buildings:

- Phase 1, the founding period of the camp, these buildings were destroyed by fire,

- Phase 2 falls in the time after the Marcomann Wars ,

- Phase 3 in the first half of the 3rd century.

- Phase 4, early 5th century, it could only be proven on the basis of a dry stone wall in the western officer's house.

The houses were rebuilt again in the 2nd century. However, around 169 they burned down again. At the beginning of the 3rd century, the houses were rebuilt on the old floor plans, but their interiors were arranged completely differently. The buildings from late antiquity that they replaced were no longer based on the classic building scheme. One assumes that they no longer existed in their old form at this time. The thoroughfare between the two houses was also built over with a wall during this time.

Two of the tribune houses could be examined more closely when the new houses at Hoher Markt No. 3 and 4 were built. They were separated by an alley two meters wide. The parts of the wall that are still visible today are the remains of the rear main walls; a section of the front was exposed in Landskrongasse. The living and utility rooms were each grouped around an inner courtyard (atrium) , which was surrounded by a portico . Its spaces were walled up in the 3rd century. The walls and floors of individual rooms could be heated with hypocausts or hollow brick channels and provided with terrazzo or clay coverings. The remains of one of the underfloor heating systems and a drainage channel can be viewed in the showroom in the cellar of the Roman Museum on Hohen Markt. The walls were probably richly decorated with paintings (floral motifs). The ceiling beams were supported by marble columns and capitals. The roof structures probably reached a span of up to 12 m and were designed as frame constructions.

Thermal bath

The approx. 100 m × 66 m large storage bath stood in the praetentura of the fort (Marc-Aurel-Straße / Ruprechtsplatz / Hoher Markt) and was apparently used until late antiquity. It was equipped with cold and warm water basins, a sweat bath ( sudatorium ) and an inner courtyard. The bathing facility was probably built over the ruins of a warehouse (horreum) . When the Berghof was demolished , massive Roman-era constructions such as apses and hypocaust structures came to light. In 1962, Herta Ladenbauer-Orel found a one-meter-thick wall in Sterngasse / Marc-Aurel-Strasse, made up of 20 cm × 20 cm × 30 cm ashlar stones from the bathing complex. An apse of the caldarium was uncovered on the high market . A canal ran beneath today's meat market, and the sewage was probably disposed of through this. Further sewer sections and remains of clarifiers were observed in Marc-Aurel-Straße. The ruins of the camp bath were expanded into a fortified settlement or castle from the early Middle Ages.

Camp hospital

The Valetudinarium was loud Alfred Neumann in the northwest corner of the camp, approximately in the range of today's Salvatorgasse. This assumption is based only on the local find of an altar consecrated to the gods Jupiter, Apollo, Sirona and Aesculapius, which was walled in in the church Maria am Gestade ( Spolie ). In this area, some medical equipment was also found in an ancient rubbish pit.

Fabrica

In the area of the Vienna Central Fire Brigade, Am Hof, the remains of a workshop building were found between 2007 and 2008. Such a functional building has not yet been found in Vindobona. The exact dimensions of the building could no longer be determined, since the eastern area is disturbed by a parking garage built in the 1960s. A total of four rooms in the fabrica could be excavated. The western and southern outer walls consisted of rubble stones bound in lime mortar. The oldest findings were three pits in the two southernmost rooms, which had probably served as ovens. Remnants of slag and iron objects suggest a metalworking workshop there. Several mid-imperial floor levels and levels (can be dated from coin finds) prove that the building was used continuously until the end of the 4th century. They were badly burned and streaked with ashes. Late antique levels still contained residual blue paint. Further paint residues on ceramic fragments make the rooms likely to be used as painters' workshops.

Warehouse streets

In 1937 Erich Polaschek succeeded in uncovering the approx. 13 m wide via principalis , the west-east main camp road. By uncovering the column bases and the remains of porticos that accompanied the street on both sides, its exact course could also be reconstructed (from today's shoulder street, Landskrongasse to Ertlgasse and Kramergasse). In 1951, in Salvatorgasse, part of via praetoria , the north-south main road and two of its sewers were cut. Part of the street macadam of the via sagularis came to light in the southeast . To the west of the fabrica , another of the camp streets ( via vallaris ) was exposed between 2007 and 2008 . Their surface consisted of several layers of gravel and gravel, interspersed with brick chippings and brick fragments. A drainage channel and a sidewalk ran between via vallaris and the buildings adjoining it to the east. A total of four road surface and sidewalk levels could be distinguished. Numerous finds were made in the drainage channel as well as in the sidewalk area, such as B. an amber and a jade pearl, a hinge brooch and a bony knife handle.

Sewer system

The Romans probably built a sewer on the eastern wall of the camp, which existed until modern times and was known as Möhring. During the construction of the new fire brigade control center at the courtyard, the once up to 1.80 m high ring canal of Wallstrasse (via sagularis) , which provided drainage for the camp into the Ottakringer Bach, was cut and preserved. It accompanied the wall on the inside of the camp and ran directly under Wallstrasse. The exposed section in the cellar showroom presumably absorbed the waste water from the southern part of the camp and led it into the Tiefen Graben to the Ottakringer Bach. It was covered with flat stone slabs and in places with sewer grilles. The bottom of the canal consisted of roof tiles laid lengthways (ledge tiles), two of which came to lie next to each other in the middle of the canal with the ledges. The bricks bore the stamp of the Legio XIII in the form of a tabula ansata . At the end of the stamp are the names of the centurions who supervised the brick production. The soles of the canals from Roman times uncovered in Vienna also consisted mostly of roof tiles, which were laid with the two lateral retaining beads upwards, but sometimes just a layer of concrete was poured on. The covers of the mostly square or rectangular ducts consisted of 5 to 15 centimeters thick stone slabs. For smaller canals, clay pipes in the form of a conical socket with a diameter of around 20 centimeters were made. The individual clay pipes were then plugged into one another and thus assembled into a cable. The rainwater was led into the canals through stone inlet grids. The grilles were made of about ten centimeters thick square stone slabs and provided in a star shape with rosette-like openings.

garrison

The chronology of the Roman troop history of Vienna from the Domitian period onwards could be reconstructed in a somewhat satisfactory manner on the basis of numerous gravestones, consecration altars and over 3000 brick stamps as well as building inscriptions. Ceramic remains from the 1st district in favor of the presence of Roman troops no later than the middle of the 1st century. AD. The brick temple come mainly from three legions , the Legio XIII , the Legio XIIII and Legio X . The first two were only in Vindobona for a relatively short time , but they did the main work in expanding the camp. In Vienna there were not only legions; at least one auxiliary force unit (auxiliary cavalry ala I Flavia Augusta ) was also demonstrably stationed there. The cavalry units were probably housed in their own fort in the 1st district. Brick stamps of auxiliary troops are known from the ala I Thracum stationed in Carnuntum in the 2nd century and the archers of the cohors I Aelia sagittariorum from the Klosterneuburg fort for Vienna. In the course of the extensive military reforms under Diocletian, a Dux limites (military leader of the provincial army) received supreme command over the units stationed in Pannonia I from 305 onwards . By 311 the Legio X was probably reduced to 2,000 or 1,000 men and added to the newly formed stationary border troops, the so-called riparenes .

| Time position | Troop name | comment | Illustration |

| 1st to 2nd century AD (89 / 97–101) |

Legio XIII Gemina ("the thirteenth twin legion ") |

The Legion probably began building the camp between AD 89 and AD 92/93. It was probably moved from Poetovio to the Danube in Domitian's wars between 89 and 92 and 98, respectively . Hundreds of their brick stamps and building inscriptions from their Centuries were recovered in Vienna . However, gravestones of their relatives have not yet appeared. Your construction crews probably completed the most important buildings of the camp ( principia, praetorium , towers) and the camp wall. The floors of the canal system, especially along the main roads of the camp and the via sagularis , were built almost exclusively from the stamped bricks of this legion. | |

| 2nd century AD (101–114) | Legio XIIII Gemina Martia Victrix ("the fourteenth twin legion of Mars, the victorious") | The Legio XIII was assigned by Traian from 101 AD to the Dacian Wars and replaced by the Legio XIIII for ten years . She continued the construction of the camp together with the ala Batavorum before it was moved to Carnuntum in 114 AD . The presence of this legion can also be proven through building inscriptions, additionally through consecration altars and despite the shortness of their stay through a surprising number of brick stamps. These could also have been delivered from Carnuntum , since the Legion was stationed there until the 5th century. | |

| 1st century AD (before 41) | Legio XV Apollinaris ("the fifteenth legion of Apollo") | The fragment of a tombstone of the legionnaire C. Atius, a member of this legion, which was discovered on Stephansplatz , is the oldest Roman written monument to date in Vienna and is particularly important for the history of the early Vindobona . It is assumed that the epigraphic and stylistic features of the inscription come from the reign of Tiberius (14–39 AD). The legion was probably still in Savaria at that time and around 100 soldiers had been assigned here. The legionnaire served ten years and died at the age of 28 while still on active duty in Vindobona . The inscription is the only archaeological evidence that a vexillation of this legion was stationed in Vienna, at least for a short time , before it moved into its camp in Carnuntum . Their pre-Claudian stationing location is unknown. | |

| 2nd to 5th centuries AD (114 to 5th centuries) |

Legio X Gemina pia fidelis ("the tenth twin legion , the dutiful and faithful") |

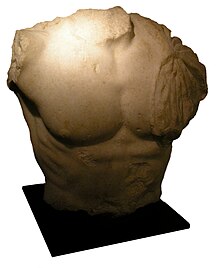

She probably finished the camp. Before AD 107, Emperor Trajan divided Pannonia into Pannonia superior and Pannonia inferior . The legion was moved from Aquincum to Vindobona as part of the Pannonia superior army in 114 AD and thus advanced to become the Viennese “house regiment”. It is not only easy to understand through inscriptions on a number of soldiers and veterans' grave stones, dedications and brick stamps, but also through a relief on which the heraldic animal, the bull, is depicted. It was most likely attached to the east gate as a metope . A remaining troop ( vexillatio ) of the legion was apparently in Vindomarae until the 5th century , since in the Notitia Dignitatum a praefectus legionis decimae geminae under the command of the Dux Pannoniae Primae et Norici Ripensis appears. | |

| 1st to 2nd century AD (89-101) |

Ala I Flavia Domitiana Augusta Britannica milliaria civium Romanorum bis torquata ob virtutem ("the first Flavian cavalry squadron of the British , Roman citizens, 1000 strong, excellent for bravery") |

The first historically tangible Roman troop in Vindobona was probably assigned to protect the building vexillations of the Legio XIII . Their stationing is proven by the discovery of three gravestones (Hofburg / Stallburg , grave stele of Titus Flavius Barbus, Titus Flavius Draccus and Titus Flavius Verecundus). The presence of the British can almost certainly be narrowed down to the period from 93 to 101 AD based on the inscriptions on them. Perhaps it came to Vindobona in the course of Domitian's war against Marcomanni and Quadi . From 101 she took part with the Legio XIII in the campaign of Trajan against the Dacians. | |

| 1st to 2nd centuries AD (101–114) |

Ala I Batavorum milliaria pia fidelis ("the first Batavian cavalry squadron, 1000 strong, the dutiful and loyal") |

The cavalry force, originally from the Lower Rhine region, was probably in Vindobona from 101 to 118/119 AD . On the basis of a military diploma from the year 112, Barnabás Lőrincz assumes that the troops replaced the ala I Britannica at that time . After that she could have been moved to Schwechat , where she was possibly also involved in the founding of the Ala Nova Castle . | |

| 1st century AD |

Cohors I Aelia sagittariorum ("the first Aelian cohort of archers") |

Only finds of brick stamps, the troop is also verifiable for the Klosterneuburg fort . | |

| 1st century AD | Ala I Thracum ("the first cavalry squadron of the Thracians ") | Finds of brick stamps. | |

| 1st to 5th century AD | Classis Pannonica and Classis Histricae ("Pannonian Fleet, Danube Fleet") | Fleet soldiers (liburnari) of the classis Pannonica can also be expected in Vindobona due to its strategically important location on the Danube. From the Middle Imperial period, Vindobona was also a naval base for a squadron of the Danube fleet. For late antiquity, the Notitia dignitatum , a praefectus classis Histricae, [C] Arr [n] unto siue Vindomanae under the command of the Dux Pannoniae Primae et Norici Ripensis , is recorded. The relocation of the classis Histricae from Carnuntum to Vindobona in the 4th century probably also brought about a significant upgrade of the location. |

port

On the northern front of the legionary camp, at today's staircase (Rabensteig 3) to the Maria am Gestade church, some Roman ashlar stones were found in 1999 at the foot of the camp plateau, which were probably once part of the quay wall of a late antique port facility. The difference in height between the site and the camp plateau was about twelve meters. Halfway up, between 1901 and 1902, a path paved with stone slabs and the remains of a fortification located directly on the ancient steep slope on the banks of the Danube came to light (gate system with ashlar in front). It is not known when the first port facilities were built. Due to the construction, the findings could be dated to late antiquity (4th century).

Civil settlements

From the 1st to the middle of the 3rd century AD, larger canabae legionis (camp town) that were under military administration emerged on the gravel terrace around the legionary camp . At the same time, the civil town, later the Municipium , developed in the area of today's 3rd District (Landstrasse) .

Storage city

development