Savaria

Savaria , completely Colonia Claudia Savaria , was a Roman city in the area of today's western Hungarian city of Szombathely in Vas County . Significant structural remains can be seen today in the Járdányi Paulovics István ruins garden . In addition, a partial reconstruction of the local Iseum was completed in August 2010 . The Savaria Museum is attached to this building and presents the most important finds from the city and the surrounding area. Through the elevation to the provincial capital in the beginning of the 2nd century , Savaria became a regional center , which most likely owed its wealth to the Amber Road running through it. Szombathely is most likely the oldest Pannonian city foundation and thus the oldest Roman city on today's Hungarian territory .

location

Savaria was founded on the southwestern edge of the Little Hungarian Plain . To the west and north, the eastern edge of the Alps emerges as a clear hilly landscape in the terrain, which flows into the Pannonian Plain immediately east of the city . To the north-west lies the Günser Mountains, which are important for the ancient water supply . As in the north-east and east, the country flattens out to the south as far as Raab , which is around 25 kilometers away . Today the Őrség National Park and the Zala (Zalai-dombság) hill country begin on the south bank of the river .

Early research history

Early interest in Roman antiquity was aroused in the 15th century, but it was only at the suggestion of János Szilys (1735–1799), the first bishop of the Szombathely diocese , founded in 1777, that the clergyman and scholar Stephan Schönwiesner (1738–1818) wrote under the title Antiquitatum et Historiae Sabariensis ab origine usque ad praesens tempus libri IX cum iconibus a first monograph of the city, which was published in 1791. In 1871 the Archaeological Society was founded in Szombathely. One of the most important goals of this association was to found a museum. After its establishment, the principal of the Premonstratensian Chorherren High School, Vilmos Lipp (1835–1888), who was interested in archeology, published in the journal Archaeologiai Értesítő (Archaeological News) about the scientific work in Szombathely . The premonstratensian and historian Antal Tibor Horvath (1889–1964), who worked in the city until 1936, was one of the important personalities before the Second World War . In the 1920s, the archaeologist Nándor Fettich (1900–1971) in particular expanded the view of the ancient urban topography considerably. From 1938 to 1941 the late antique palace hall of the governor was excavated. Their valuable mosaics were given two temporary protective structures in 1942, which had to exist for decades and ultimately could not fulfill their protective function.

General city history

Surname

The name is already mentioned by Pliny the Elder, who lived in the 1st century AD, in his Naturalis historia . The city is also mentioned by Claudius Ptolemy in the 2nd century. In the Tabula Peutingeriana , a late antique map of the Roman road network from the 4th century, the city is referred to as Sabarie . The place can also be found in the Notitia dignitatum , a Roman state manual from the first half of the 5th century.

founding

Savaria may have emerged from a fortress built during the Roman occupation of Pannonia from 9 AD. Little is known from the earliest phase, however. Also, no pre-Roman settlement sites have been discovered in the area of the historical city area. The expansion of the Amber Road, which is believed to have begun during the reign of Emperor Tiberius (14–37 AD), was probably a decisive factor in the rise of the Amber Road at an unknown point in time during the reign of Emperor Claudius (41–54 AD) Colonia founded on the Savarias brook (today: Perint) (see Velem-Szentvid hilltop settlement ). The deduction colony was named Colonia Claudia Savaria after the donor emperor and the brook . It is possible that the area of Illyricum Inferius, which was previously under Roman military administration, was converted into the province of Pannonia and a civil administration was introduced. The first residents were veterans of the Legio XV Apollinaris .

1st to 5th century

During the reign of Emperor Trajan (98-117) the division of the province of Pannonia into two parts was decreed into Upper and Lower Pannonia. This had important effects on the further history of the town, as Savaria now became the civil administrative center of Upper Pannonia. This clear assignment of the middle-imperial provincial civil administration by scientists from the Savaria Museum in Szombathely has also aroused resistance in the past. The ancient historian Rudolf Haensch said in 1997 that in addition to Savaria, Carnuntum ( Petronell-Carnuntum ) or Poetovio ( Ptuj ) could also be used as official seats. In inscriptions, Savaria is attested, at least for late antiquity, as the capital of the province of Pannonia I through the Notitia dignitatum . In the course of the appointment, important construction work was initiated. There were official and administrative buildings for the provincial self-government as well as the temples and buildings of the imperial cult and its priesthood typical for provincial capitals. The archaeologists found their remains southwest of the walls of the ancient city, on the west bank of the Savarias stream , which was known in late antiquity as Sibaris .

After 150 and during the first half of the 3rd century, new settlers from Italy, southern Gaul and the eastern provinces made up the majority of the population. The proportion of the latter group increased especially after the Marcomann Wars . The main reasons for their arrival were troop movements, but also traders who tried their luck in the metropolis on Bernsteinstrasse. The new residents from the eastern provinces also brought new burial customs with them. From the end of the 2nd century onwards, a remarkable number of people were buried in sarcophagi without inscriptions. The end of the Marcomannic Wars also heralded a certain new heyday, which was particularly marked by extensive imperial renovation work on public buildings at the beginning of the 3rd century. Otherwise, very little is known about the city's history in the 3rd century. As in many parts of the empire, however, the written tradition in the form of inscriptions clearly declined during this century, which is seen by scientists as a sign of the often chaotic conditions at the time.

In 303 Quirinus , the bishop of Siscia , was executed in the city as part of the persecution of Christians . In 316/317 St. Martin of Tours was probably born in Szombathely. On the other hand, the Martinsberg Archabbey claims that the saint was born near it, as there was an ancient place called Savaria there too .

In 308, a political reorganization of Pannonia was decided in Carnuntum, chaired by the old emperor Diocletian. Savaria became the seat of the newly founded province of Pannonia Prima . For representation purposes, a monumental single-nave palace auditorium was built on the forum area - architecturally comparable to the larger Basilica of Constantine in Trier - which ended with a semicircular apse. The entrance to this building was a large peristyle courtyard, inside a first-class, 40.40 × 16.40 meter mosaic adorned the floor, which was heated throughout, and the walls were paneled with colored marble. In the southern neighborhood of the building, fragments of statues from the Capitoline Triassic were discovered. Ancient authors mention the palace in Savaria several times and report the presence of several emperors. Constantine the Great (306–337), Constantius II (337–361) and Valentinian I (364–375) resided here .

In the 5th century, the city was gradually abandoned by its residents (mostly Ostrogoths ) who moved to safer regions of the Roman Empire. On September 7, 456, an earthquake devastated the largely abandoned buildings. Partly badly deformed road surfaces that came to light during the excavations are evidence of this event.

Post-Roman development

During the first Avar campaign in 791, Sabaria was touched by the retreat of the defeated Carolingian army under the leadership of Charlemagne (747 / 748-814). In the early 9th century the place marked the southernmost end point of the Franconian Avar principality and was possibly developed into a secular or ecclesiastical center at this time. After the dissolution of the Avar principality, the East Franconian county of Stein am Anger was created and Sabaria became the suburb of a political unit again. German settlers had coined the city name "Stein am Anger" - today "Steinamanger" . He referred to the ancient ruins that were found everywhere at that time. Nevertheless, the late antique name remains in the writings and documents until the Hungarian conquest . With the end of Bavarian influence, the Magyars replaced the Latin name with today's Szombathely , which translates as "Saturday market" and refers to the markets held here.

buildings

City walls and main streets

So far only parts of the ancient city walls have become known. Even the early urban layout obviously no longer followed the strictly rectangular planning grid typical of Roman cities. During the reign of Emperor Vespasian (69–79), the first city wall up to five meters high was built in a wood-earth construction, which surrounded an irregular pentagonal area. There was a three to four meter deep double pointed ditch as an obstacle to the approach.

With the elevation to the provincial capital under Traian, the expansion in stone took place. Perhaps in the second third of the 2nd century - possibly during the Marcomann Wars - there were sieges, which could be indicated by the trench fillings found by archaeologists. The Trajan city wall was preserved until late antiquity, when it was subsequently clad with limestone slabs. It is possible that the wall was created in the course of various construction lots, as small differences in the dimensions and the foundation technology can be determined in sections. The archaeologists find the different floor plans of the towers particularly problematic. So far not all of Savaria's city gates have been identified.

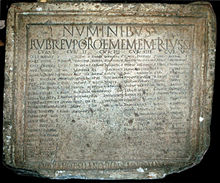

In addition to the north and south gates through which Bernsteinstrasse led, there were presumably two further gates each in the west and east. The oldest milestone of Pannonia so far emerged from the ground within the city walls near the south gate. It had already been built into the pavement of Amber Street as a heavily fragmented spoil in ancient times . His inscription, which has been partially preserved, gave the distance from Rome to Savaria: 675 miles. The mention of Rome on a milestone in the province is very rare. Its position and the distance given could be related to the Amber Road or the foundation of the Colonia . Despite the imperial name, which has not been preserved, the stone can be dated to the 1st century, as it was built in at the beginning of the 2nd century.

Inner city streets and insulae

The insulae separated by the street system did not follow the usual standardized scheme; so the archaeologists encountered both smaller and larger apartment blocks. In some areas, the larger insulae were subsequently divided into two or three plots. Trapezoidal or diamond-shaped plots can also be found south and west of the city center. It was only after the foundation scheme with the first insulae and the early road network was laid out that the infrastructural expansion of the roads with solid paving and the installation of the sewerage system took place during the first half of the 2nd century. The paving of irregular basalt slabs came from Mount Ság to the east. The material for the stone structures was largely obtained from a quarry near today's Felsőcsatár in the west.

The width of the street varied. The Amber Road was measured at the Isis sanctuary in front of the southern city wall with a width of 12 meters. Behind the southern city gate, in the city center, it was only 6.6 meters. The average street width was 5 to 6 meters, narrow streets between the insulae were only 2 to 3 meters wide. Since the rammed stone gravel of the road foundation extended over the full width from house wall to house wall, the sidewalks were only separated from the street pavement by small, flat, vertical slabs and the stone gravel was used as a walkway for the sidewalk. Along the main streets the sidewalks ran under arcades, in the side streets these porticos were only partially to be found.

Public buildings

During the Flavian era in the second half of the 1st century, the forum and the capitolium were built . By the end of the century, work on the Temple of the Capitoline Triassic was finished. Fragmented cult statues and larger structural elements make it seem possible to look for this temple in the area of today's bishop's palace. To the south, outside the city walls, were holy areas for oriental cults, such as the large Isis sanctuary and a nearby Dolichenus temple. To the northwest of these cult areas there were two Mithras altars, so that a corresponding sanctuary in Savaria can be assumed. In the eastern part of the city a fragment of an inscription was discovered which adorned a temple donated by Emperor Claudius. Other altars discovered in today's ruin garden are dedicated to Jupiter , Mercury and other deities. During the reign of Septimius Severus (193-211), who was appointed emperor by the Pannonian legions and to whom the province of Upper Pannonia in Savaria swore allegiance, several major construction projects took place. This is how the Iseum was embellished. In addition to a marble cladding, it received new columns and a new facade. The central main frieze of the temple's entablature, which has been partially preserved, shows Isis- Sothis . One of her raised hands holds a sistrum and she rides a dog that embodies the constellation of Canicula - a symbol of the annual, harvest-giving Nile flood. Found granite columns also suggest a renewal of the forum. Savaria as the center of the provincial imperial cult of the principate's time can be proven epigraphically several times. This is how the priests of the imperial altar of the province of Upper Pannonia and the heads of the colleges for the genius of the province of Upper Pannonia are named.

Pottery district, municipal brickworks and customs post

Most of the pottery kilns were excavated in the northern and northwestern parts of the city. There was a customs post at the western city gate, which was preserved as part of the ruin garden. There was the bronze round stamp of a tenant of the eighth tax of both Pannonian provinces. Traders had to pay customs when entering or leaving the city according to the value of their goods. The existence of a public brick factory could also be determined from the finds. Public construction companies maintained by cities have so far only rarely been occupied in the Roman Empire. As a rule, the city council issued tenders to private entrepreneurs.

Water supply

In order to meet the great demand for drinking and service water, the Roman engineers built a 26 km long, underground, vaulted pipe system through which fresh water was brought in from the nearby Günser Mountains via collecting pipes. The route was not created on the shortest route, but rather subordinated its course to the terrain profile. In the Szombathely city area at today's Bagolyvár (Eulenburg) the water tower reached the end of the line. From here the public and private facilities were supplied with water.

Burial grounds

In accordance with Roman customs, the tombs were laid outside the city walls. The grave fields of the 1st to 2nd centuries were created in wide strips along the arterial roads around the Colonia . After only a few places were free on the previous grave sites from the 3rd century onwards and new, unused areas were too far away from the city, the residents also built new graves directly in front of the city wall until the 4th century the city was gradually surrounded by tombs. Archaeologists reckon with around 100,000 graves for the 400-year history of the city in Rome. However, less than one percent of these are known to date.

literature

- Lajos Balla, András Mócsy, Tihamér Szentléleky: The Roman Stone Monuments of Savaria. Akadémiai Kiadó, Budapest 1971.

- Lajos Balla: On the history of the religious life of Savaria. In: Acta classica universitatis scientiarum Debreceniensis. 3, 1967, pp. 67-76.

- László Barkóczi, András Mócsy: The Roman Inscriptions of Hungary (RIU). 1. Delivery: Savaria, Scarbantia and the Limes line Ad Flexum – Arrabona. Akadémiai Kiadó, Budapest 1972.

- Dorottya Gáspár: A Greek escape table from Savaria. In: Tyche . 5 (1990). Pp. 13-16.

- Terézia Buócz: Lapidarium Savaria Museum. Vas County Museums, 1994, ISBN 9637206574 .

- Péter Kiss, Ottó Sosztarics: A special milestone from Savaria. In: Savaria. 23/3, 1996-1997, pp. 101-113.

- Marie-Louise Krüger: The reliefs of the urban areas of Scarbantia and Savaria. Publishing house of the Austrian Academy of Sciences, Vienna 1974, ISBN 3-7001-0475-8 .

- András Mócsy : Pannonia and Upper Moesia. Routledge & Kegan Paul, London 1974, ISBN 0-7100-7714-9 .

- Ottó Sosztarics: A milestone from Savaria. In: Susanne Biegert (Ed.): From Augustus to Attila. Life on the Hungarian Danube Limes (= writings of the Limes Museum Aalen. Volume 53). Konrad Theiss Verlag, Stuttgart 2000. ISBN 3-8062-1541-3 . P. 57.

- Ottó Sosztarics: Topographical research in the southern part of Savaria. The emergency excavation in the main square of Szombathely (1991–1992). In: La Pannonia e l'impero romano. Electa, Milan 1995, pp. 233-241.

- Tihamér Szentléleky: A szombathelyi Isis szentély. The Szombathely Iseum. Képzőművészeti Alap Kiadóvállalata, Budapest 1965.

- Endre Tóth : A victory monument from the age of Domitianus and a senatorial cursory inscription in Savaria. In: Acta Archaeologica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae. 35, 1983, pp. 3-61.

- Endre Tóth: The mosaic floor of the Aula Palatina of Savaria. In: Acta Archaeologica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae. 28, 1976, pp. 301-317.

- Endre Tóth: On the historical problems of the city of Savaria and its surroundings between the 4-9. Century. In: Folia Archaeologica. 27, 1976, pp. 89-120.

- Endre Tóth: Late antique imperial palace in Savaria (the question of the so-called Quirinus Basilica). In: Acta Archaeologica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae. 25, 1973, pp. 117-137.

- Endre Tóth: Figuratively decorated loculus plate from Savaria. In: Folia Archaeologica. 23, 1972, pp. 151-182.

- János Reismann: Savaria and surroundings. Corvina Verlag Budapest 1968.

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ Manfred Kandler: The Auxiliary Fort Carnuntum, research 1977–1988. Austrian Archaeological Institute, Vienna 1997, p. 138.

- ^ Endre Tóth: Savaria római topográfiájáról. In: Vasi Szemle. 62, 2008, pp. 662-679; here p. 662.

- ↑ a b Terézia Buócz, Tihamér Szentléleky, Erika P. Hajmási, Agnes Vladár: The István Járdány Paulovics ruin garden in Svaria (Szombathely). In: Carnuntum Jahrbuch 1991. Böhlau, Graz 1992, p. 9 ff .; here: p. 45.

- ↑ Pliny, Naturalis historia 3, 146 . Cf. Elmar Csaplovics: On the topochronology of the landscape around Lake Neusiedl up to the end of the 16th century. Office of the Burgenland Provincial Government 2005, ISBN 3901517502 , p. 57.

- ↑ a b c d Herwig Wolfram: Salzburg - Bavaria - Austria. The Conversio Bagoariorum et Carantanorum and the sources of their time. Oldenbourg Verlag, Vienna 1995, ISBN 3-7029-0404-2 , p. 120.

- ↑ a b Notitia dignitatum, occ XI, 23-25.

- ↑ a b c Péter Kiss, Réka Mladoniczki, Jörg Scheuerbrandt , Eszter Harsányi: The Colonia Claudia Savaria from the middle of the 1st to the 3rd century AD Colonia Claudia Savaria a Kr. U. 1. sz. közepe és a 3rd sz. között. In: On behalf of the eagle. A római sas szolgálatában. Publius Ferrasius Avitus. Book accompanying the German-Hungarian special exhibition. Römermuseum, Osterburken 2012, ISBN 978-3-00-037759-4 , p. 41.

- ^ László Barkóczi, András Mócsy : The Roman Inscriptions of Hungary (RIU). Savaria, Scarbantia and Limes route ad Flexum-Arrabona. Adolf M. Hakkert, Amsterdam 1972, p. 13.

- ^ Endre Tóth : Roman roads in Hungary. In: From Augustus to Attila. Limes Museum Aalen. Konrad Theiss Verlag, Stuttgart 2000, ISBN 3806215413 , p. 53 ff .; here: p. 55.

- ↑ Elmar Csaplovics: On the topochronology of the landscape around Lake Neusiedl up to the end of the 16th century. Office of the Burgenland Provincial Government 2005, ISBN 3901517502 , p. 37.

- ↑ Péter Kiss, Réka Mladoniczki, Jörg Scheuerbrandt, Eszter Harsányi: The Colonia Claudia Savaria from the middle of the 1st to the 3rd century AD Colonia Claudia Savaria a Kr. U. 1. sz. közepe és a 3rd sz. között. In: On behalf of the eagle. A római sas szolgálatában. Publius Ferrasius Avitus. Book accompanying the German-Hungarian special exhibition. Römermuseum, Osterburken 2012, ISBN 978-3-00-037759-4 , p. 40.

- ↑ a b c Péter Kiss, Réka Mladoniczki, Jörg Scheuerbrandt, Eszter Harsányi: The Colonia Claudia Savaria from the middle of the 1st to the 3rd century AD Colonia Claudia Savaria a Kr. U. 1. sz. közepe és a 3rd sz. között. In: On behalf of the eagle. A római sas szolgálatában. Publius Ferrasius Avitus. Book accompanying the German-Hungarian special exhibition. Römermuseum, Osterburken 2012, ISBN 978-3-00-037759-4 , p. 46.

- ^ Rudolf Haensch: Capita Provinciarum - governor's seat and provincial administration in the Roman Empire. Kölner Forschungen, Volume 7. Verlag Philipp von Zabern, Mainz 1997. ISBN 978-3-8053-1803-7 . P. 349, note 155.

- ↑ a b CIL 3, 4170 .

- ↑ a b CIL 3, 4183 .

- ↑ Péter Kiss, Réka Mladoniczki, Jörg Scheuerbrandt, Eszter Harsányi: The Colonia Claudia Savaria from the middle of the 1st to the 3rd century AD Colonia Claudia Savaria a Kr. U. 1. sz. közepe és a 3rd sz. között. In: On behalf of the eagle. A római sas szolgálatában. Publius Ferrasius Avitus. Book accompanying the German-Hungarian special exhibition. Römermuseum, Osterburken 2012, ISBN 978-3-00-037759-4 , p. 54.

- ↑ Szilveszter Solymos: Pannonhalma. A travelguide. Archabbey of Pannonhalma, 2010, ISBN 978-963-9053-86-1 , p. 7.

- ↑ Endre Tóth: A savariai Császári palota építéstörténtéhez. In: Archaeológiai Értesítő 102. (1975). Pp. 25–45, here: p. 40.

- ^ András Mócsy : Pannonia and Upper Moesia. A history of the middle Danube provinces of the Roman Empire. Routledge & K. Paul, London, Boston 1974, ISBN 0710077149 , pp. 313-314.

- ↑ Terézia Buocz, Tihamér Szentléleky, Erika P. Hajmási, Agnes Vladár: The István Járdány Paulovics ruin garden in Savaria (Szombathely). In: Carnuntum Jahrbuch 1991. Böhlau, Graz 1992. P. 9 ff .; here: p. 42.

- ^ Béla Miklós Szőke: The Danube and the last days of the Avar Khaganate. In: Gyöngyi Kovács, Gabriella Kulcsár (eds.): Ten Thousand years along Middle Danube. (= Varia Archaeologica Hungarica. XXVI). Archaeolingua, Budapest 2011, ISBN 978-963-991126-0 , pp. 265ff.

- ↑ Uta von Freeden, Herwig Friesinger, Egon Wamers (ed.): Faith, cult and rule. Phenomena of the Religious. (= Colloquia on prehistory and early history. Volume 12). Roman-Germanic Commission of the German Archaeological Institute, Frankfurt am Main 2009, ISBN 978-3-7749-3663-8 , p. 400ff.

- ↑ AE 2000, 1195 : A Rom (a) S (avariam) m (ilia) p (assuum) / DCLXXV .

- ↑ Péter Kiss, Réka Mladoniczki, Jörg Scheuerbrandt, Eszter Harsányi: The Colonia Claudia Savaria from the middle of the 1st to the 3rd century AD Colonia Claudia Savaria a Kr. U. 1. sz. közepe és a 3rd sz. között. In: On behalf of the eagle. A római sas szolgálatában. Publius Ferrasius Avitus. Book accompanying the German-Hungarian special exhibition. Römermuseum, Osterburken 2012, ISBN 978-3-00-037759-4 , p. 47.

- ↑ a b Péter Kiss, Réka Mladoniczki, Jörg Scheuerbrandt, Eszter Harsányi: The Colonia Claudia Savaria from the middle of the 1st to the 3rd century AD Colonia Claudia Savaria a Kr. U. 1. sz. közepe és a 3rd sz. között. In: On behalf of the eagle. A római sas szolgálatában. Publius Ferrasius Avitus. Book accompanying the German-Hungarian special exhibition. Römermuseum, Osterburken 2012, ISBN 978-3-00-037759-4 , p. 48.

- ^ Anne Kolb: Roman Milestones: State of Research and Problems. In: Regula Frei-Stolba (Ed.): Settlement and traffic in the Roman Empire. Settlement and traffic in the Roman Empire - Roman roads between securing power and shaping the landscape. Verlag Peter Lang, Bern 2004, ISBN 3039100300 , p. 151.

- ↑ Péter Kiss, Réka Mladoniczki, Jörg Scheuerbrandt, Eszter Harsányi: The Colonia Claudia Savaria from the middle of the 1st to the 3rd century AD Colonia Claudia Savaria a Kr. U. 1. sz. közepe és a 3rd sz. között. In: On behalf of the eagle. A római sas szolgálatában. Publius Ferrasius Avitus. Book accompanying the German-Hungarian special exhibition. Römermuseum, Osterburken 2012, ISBN 978-3-00-037759-4 , p. 49.

- ↑ Péter Kiss, Réka Mladoniczki, Jörg Scheuerbrandt, Eszter Harsányi: The Colonia Claudia Savaria from the middle of the 1st to the 3rd century AD Colonia Claudia Savaria a Kr. U. 1. sz. közepe és a 3rd sz. között. In: On behalf of the eagle. A római sas szolgálatában. Publius Ferrasius Avitus. Book accompanying the German-Hungarian special exhibition. Römermuseum, Osterburken 2012, ISBN 978-3-00-037759-4 , p. 52.

- ↑ a b Péter Kiss, Réka Mladoniczki, Jörg Scheuerbrandt, Eszter Harsányi: The Colonia Claudia Savaria from the middle of the 1st to the 3rd century AD Colonia Claudia Savaria a Kr. U. 1. sz. közepe és a 3rd sz. között. In: On behalf of the eagle. A római sas szolgálatában. Publius Ferrasius Avitus. Book accompanying the German-Hungarian special exhibition. Römermuseum, Osterburken 2012, ISBN 978-3-00-037759-4 , p. 53.

- ↑ Reinhold Merkelbach : Isis regina - Zeus Sarapis. The Greek-Egyptian religion depicted according to the sources. Saur, Munich, Leipzig 2001, ISBN 3-598-77427-3 , p. 588 (fig.).

- ^ Werner Jobst: Cults and sanctuaries in the Eastern Alps as an expression of local identity. In: Andreas Schmidt-Colinet (Ed.): Local identities in the peripheral areas of the Roman Empire. Files from the international symposium in Wiener Neustadt, 24. – 26. April 2003. Wiener Forschungen zur Archäologie, 7, Vienna 2008, ISBN 978-3-901232-97-8 , pp. 125–132; here: p. 127.

- ↑ CIL 3, 4168 .

- ^ AE 1968, 423 .

- ↑ a b Péter Kiss, Réka Mladoniczki, Jörg Scheuerbrandt, Eszter Harsányi: The Colonia Claudia Savaria from the middle of the 1st to the 3rd century AD Colonia Claudia Savaria a Kr. U. 1. sz. közepe és a 3rd sz. között. In: On behalf of the eagle. A római sas szolgálatában. Publius Ferrasius Avitus. Book accompanying the German-Hungarian special exhibition. Römermuseum, Osterburken 2012, ISBN 978-3-00-037759-4 , p. 51.

- ↑ Alexander Weiß: slave of the city. Studies of slavery in the cities of the Roman Empire. Steiner, Wiesbaden 2004, ISBN 3-515-08383-9 , p. 133.

- ↑ Péter Kiss, Réka Mladoniczki, Jörg Scheuerbrandt, Eszter Harsányi: The Colonia Claudia Savaria from the middle of the 1st to the 3rd century AD Colonia Claudia Savaria a Kr. U. 1. sz. közepe és a 3rd sz. között. In: On behalf of the eagle. A római sas szolgálatában. Publius Ferrasius Avitus. Book accompanying the German-Hungarian special exhibition. Römermuseum, Osterburken 2012, ISBN 978-3-00-037759-4 , p. 50.

Remarks

Coordinates: 47 ° 13 ′ 55 ″ N , 16 ° 37 ′ 12 ″ E