Common ivy

| Common ivy | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Common ivy |

||||||||||||

| Systematics | ||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

| Scientific name | ||||||||||||

| Hedera helix | ||||||||||||

| L. |

The common ivy , also common ivy or short ivy ( Hedera helix ), is a species of the genus ivy ( Hedera ) within the family of the Araliaceae . Landscape names include Epheu (p and h spoken separately), Baumwinde and, albeit ambiguously, Eppich . The ivy was named Medicinal Plant of the Year 2010 in November 2009 .

Surname

The origin of the word "ivy" is uncertain. Old High German passed down, among others, ebihouwi, ebhouwe, ebihewe, ebah, ebahi, ebahboum, ebboum, Middle High German ebehöu, ephöu, early New High German Ebheu, Epheu . Today's spelling (and the pronunciation based on it) Ifeu is based on a misinterpretation of the spelling ph as f, which arose in the 17th century . The word was no longer transparent early on; Already in Old High German ebihouwi there is a reinterpretation of the composition with “hay” (due to its use as deciduous hay), in Old High German ebboum one with “tree”. The fore link eb- has already been assumed to be related to the Latin ibex 'Capricorn' and thus a basic meaning "climber", but this remains hypothetical.

Old High German ebah (i) and Old Low German īfig live in many German dialects as Ebich, Ebch, Ebix, Ebx, Ebsch, Ewich, Ewisch, Ewix, Ewek and similar, Old High German ebihouwi in Alemannic as Abheu, Äbheu . Further reinterpretations can be found in Alemannic Räbheu (based on the also climbing "vine") and in Middle Low German iwlōf, ifflōf (based on "leaves"). The name "Baumwinde" is already used in Middle High German as boumwinde .

description

Appearance and leaf

The common ivy is an evergreen, perennial plant and a climbing tree . The common ivy is very variable in its life forms , there is sprout dimorphism . Germination takes place epigeously . At first it develops as a perennial herbaceous plant . So the ivy occasionally overgrows the ground. At this stage, its stem axes are prostrate to creeping. plagiotropic . The bark of young shoot axes is covered with fluffy star- to shield-shaped hairs ( trichomes ). Advent roots are formed at close spacing on the shoot axes . As soon as trees, fences or walls are reached, the ivy is able to climb up on them by means of adherent roots; He climbs heights of 20 or rarely up to 30 meters. The common ivy is the only root climber native to Central Europe . After a few years, the stems begin to become woody and Common ivy develops from shrub to shrub , vine until it rarely grows like a tree. Ivy can reach a maximum age of 450 years, age forms can appear around 20 years after germination. Adult specimens have rounded and upright, orthotropic shoot axes. These shoot axes are always rootless. Lignified trunks can reach a diameter of up to 30 centimeters.

In the common ivy, heterophylly is present. The alternate arranged leaves are divided into petiole and leaf blade. The simple, leathery leaf blades are bare. On the juvenile forms, the leaf blades are usually 4 to 10, rarely up to 25 centimeters in length, palmate lobes with three to five triangular, full-margined leaf lobes. In the flowering age forms, the leaf blades are egg-shaped to rhombic and not lobed with a length of 6 to 10 centimeters. The top of the leaf is glossy dark green, often with lighter veins , and the underside of the leaf is lighter. Sometimes the leaf blades turn light green to yellowish in late summer and the upper side of the leaf can be tinged purple in winter. There are no stipules .

Inflorescence and flower

Terminally in threes to sixth in panicle total inflorescences or individually on inflorescence shafts in hemispherical to spherical, golden inflorescences about 20 stalked, inconspicuous flowers stand together. The inflorescence shafts and pedicels are covered with felty star hair.

The relatively small, yellowish-green flowers are hermaphrodite, radial symmetry and five-fold with a double flower envelope . The five sepals are quite small and triangular in shape. The five, rarely six, free, yellowish-green petals are 3 to 4 millimeters long and triangular-ovoid and somewhat hood-shaped at the top. There is only one circle with five stamens . Five carpels are fused to form a subordinate five- chamber ovary. The five styluses stand together to form a column. The nectar secretion occurs on a domed disc that surrounds the ovary.

Fruit and seeds

The fruits stand close together in the fruit stands. The bluish or greenish-black, rarely yellow or white berries when ripe are spherical with a length of 5 to 9 millimeters and a diameter of 6 to 9 millimeters and have an average weight of 281.5 mg. The berries contain one to five seeds in the purple pulp . The seeds have a length of 5.7 millimeters and a diameter of 3.7 millimeters. The whitish seed coat is wrinkled. The small embryo has two germ layers ( cotyledons ). The endosperm is ruminate.

Chromosome set

The number of chromosomes is 2n = 48; based on the basic chromosome number of the genus Hedera of x = 12, tetraploidy is present.

Ecology and phenology

The common ivy is a chamaephyte , phanerophyte or liana . In the shade or with plenty of light, the leaves (shade and sun leaves) look different. Deciduous leaves are formed throughout the growing season from March to October, but particularly many develop between April and May. A single, evergreen leaf lasts for about three to four years, the main time of leaf fall is in late spring.

Protandry is present in common ivy . It is self-incompatible (self-fertilization and seed set is genetically prevented), cross- pollination is required, which is ensured by a large number of insect species. With a late flowering period in the months of September to October, ivy is a specialty within the Central European flora with its plants that mainly bloom in the spring and summer months. Because of this late flowering period, ivy is an important source of food for bees , wasps and hoverflies . Of the butterflies, the admiral visits the flowers. The ivy silk bee has even specialized exclusively in ivy pollen for rearing its brood ( monolecty ). In areas other than Central Europe, the flowering period is sometimes in other months.

The fruits ripen between January and April. The berries are eaten by the common redstart , the blackcap , the starling , the blackbird and the robin , which in this way spread the seeds ( endochory , digestive spread).

Occurrence

The common ivy is native to western , central and southern Europe from the plains to the middle mountain ranges, in the north its distribution area extends to southern Sweden , in the east to Turkey.

Forests and floodplain forests , quarries and ruins are preferred as locations . In the area of the alluvial forests, if the ivy climbs up on the trees, this indicates higher humidity. This is usually accompanied by a change in the leaf shape in the upper area. The ivy does not harm the overgrown tree, and there is no extensive competition with the other ground vegetation. In Central Europe it is a species of the Querco-Fagetea class. In the Allgäu Alps in Bavaria, between Schlipfhalden and the Klösterlealpe near Balderschwang , it rises to an altitude of 1180 meters.

The common ivy comes from the tropical forests of the Tertiary . This is reminiscent of the tips of its leaves, which quickly drain the water away.

In the course of European colonization, the common ivy was spread over large parts of the world. In many temperate climates ( North America , Australia , New Zealand ) it occurs as a neophyte and is sometimes controlled as an invasive plant . For example, the state of Oregon bans the sale and import of ivy. It is being fought as an invasive species in Vancouver , Canada . In Australia, it is viewed as an invasive plant that should be eliminated. In New Zealand too, ivy is considered an invasive plant, the spread of which should be inhibited.

Taxonomy

Hedera helix was first published in 1753 by Carl von Linné in Species Plantarum , 1, p. 202. Synonyms for Hedera helix L. are: Aralia capitata Jacq. , Hedera caucasigena Pojark. , Hedera helix subsp. caucasigena Takht. & Mulk. , Hedera taurica (Paul) Carrière. Homonym of Hedera helix L. Hedera helix Lowe (published in Richard Thomas Lowe : A Manual Flora of Madeira , 1864, p. 376).

Tree damage from ivy

In popular belief, sometimes also in silviculture, ivy is said to have numerous damaging effects on trees. So it should "suck out" trees with its roots, overgrow the tree crown and take the light from the tree, cut off the tree bark from access to air and light, "strangle" the trunk, weaken the tree through its weight and the risk of wind or Increase snow breakage and compete with the tree for water and nutrients. There is different information in the specialist literature on the possibility that the ivy could damage its carrier trees. The majority are of the opinion that ivy is harmless to large tree species, but smaller trees such as B. apple trees or large shrubs such. B. can cause hawthorn to die by overgrowing.

The adherent roots of the ivy cannot absorb any nutrients, there is no parasite on trees with the help of the aerial roots. Young adherent roots can, however, transform themselves into nutrient roots in a suitable moist environment. In one case it has been reported that such a nutrient root has pushed itself several centimeters under the bark of a fir tree. The impression that an ivy is growing out of a tree can, in very rare cases, arise when a growing tree surrounds an ivy with its trunk.

Ivy grows primarily on the trunk and strong branches of the trees. The leaves of the trees, which are important for photosynthesis, are in the forest in the upper part of the treetop, in the case of free-standing trees in the edge areas. Harmful competition from light is therefore only possible with very heavy vegetation. Such heavy vegetation with ivy could be observed in hawthorn and fruit trees. It is assumed that trees with a maximum stature height of significantly less than 20 meters can be endangered by the competition of light from ivy, especially birches and other trees with narrow crowns. No endangerment is expected for the large native tree species such as oak and ash.

A “choking” of the supporting wood, in that the growing ivy shoots prevent the entwined tree from growing thick, has been presented as a fact by several authors in the past. However, they did not provide any information on how this process has been proven. Studies of the annual rings of trees with ivy growth have not confirmed the claim.

The claim that ivy can cause damage by cutting off tree bark from light and air has not been substantiated. With several native hardwoods, however, there is a risk that bark formed in the shade will be damaged by sunburn if the shade is removed. This can be due to the cutting of trees in the area or the removal of ivy. The question of the extent to which an ivy overgrowth can provide protection against frost cracks has not yet been investigated. The hypothesis that a supporting plant could be damaged by the weight of the ivy has also not been proven. The risk of breakage due to wind and snow, due to the increased area of attack, could only be confirmed for bushes and young trees in the bush layer; this does not endanger old healthy trees.

The damage to a tree through food competition in the root area has not been proven. By shedding leaves in spring, the ivy improves soil life so significantly that its presence is less of a competition than a promotion for the support trees.

The damaging effects ascribed to ivy in a specific individual case are almost always damage to the support tree by other causes that are not so obvious in comparison to ivy vegetation. The ivy almost always goes down with its support tree, and it is very rare for a second tree to rise again. Thus, the assumed damaging effect would regularly also be self-harm.

use

Toxicity and uses in herbal medicine

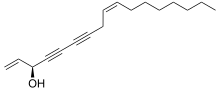

All plant parts of the common ivy are poisonous. Known poisonous ingredients are α-hederin (triterpene saponin ), which can be formed from hederasaponin C through degradation reactions (80% contained), and falcarinol . Signs of poisoning can appear after ingesting two or three berries: burning sensation in the throat, diarrhea and / or vomiting, headache, increased pulse, cramps. After ingestion of large amounts (unlikely because it is very bitter), shock and respiratory failure may occur. Contact dermatids are also common due to the reaction of falcarinol with skin proteins.

Preparations made from ivy leaves are used, in low doses, for expectorant and spasmolytic properties in bronchial diseases, convulsive and irritable coughs. In higher doses, however, the extract has an irritating effect on the mucous membranes and the skin. Regardless of this, no toxic symptoms were observed in animal experiments with an ivy leaf dry extract at a peroral dose of 3 g / kg or a subcutaneous dose of 0.5 g / kg. The same tests also showed good tolerability in the case of chronic administration. Among other things, this is due to the fact that substances that are largely responsible for toxicity, such as falcarinol, do not dissolve under the usual extraction conditions.

In folk medicine , an ivy compress is recommended for nerve pain .

Historically, the contraceptive and even abortive effects of the plant are reported, which are probably due to the toxic effects: “ All pious women should be careful not to consume boiled or burnt water from this juice. "

Ivy resin (Latin gummi hederae ) was also used as a medicine. Preparations made from ivy (also called hedera nigra "black ivy") were used in antiquity to treat kidney stones, headaches, spleen pain, spider bites, ulcers, foul-smelling noses and earaches.

Use as a useful plant

Because of the saponins it contains, which have a soap-like effect, ivy can be used as a herbal detergent substitute, similar to soap herb.

The evergreen ivy was collected as deciduous hay as early as the Neolithic Age . The sometimes extremely high pollen values in several Swiss pile dwellings can only be explained by the introduction of ivy leaves for winter feeding. In Denmark and neighboring areas, too, foliage advertising can be demonstrated using the ivy curve of the pollen diagrams. The extraction of leaf hay from ivy was still a measure in modern times when there was a lack of fodder, and in southern Europe even in the 20th century.

Use as an ornamental plant

Common ivy is considered to be very suitable for greening fences, walls and facades. An overgrown ivy protects the overgrown areas from rain and from stress cracks caused by strong temperature fluctuations, and it acts as thermal insulation . In addition, the ecological importance of a green facade as a habitat for insects and a nesting place for songbirds is emphasized.

Ivy does not need any climbing aid on a not too smooth surface, as it anchors itself to the masonry with its adhesive roots. For this reason, it is also assumed that it could damage the facades. The prerequisite for damage are existing crevices and cracks in the masonry, which can be burst open by the growth in thickness of the penetrated adhesive roots. The facade must be able to bear the weight of the non-lignified parts of the ivy. Facades with damaged masonry, curtain elements and thermal insulation composites are therefore unsuitable for planting ivy.

The plant purifies the air of benzene , formaldehyde , xylenes and toluene .

Historical development

In classical antiquity , ivy was dedicated to the gods of wine. Both the ancient Egyptian Osiris and the Greek Dionysus and the Roman Bacchus were represented with wreaths of vine and ivy leaves.

The Greeks wore ivy wreaths at festive feasts, because the leaves were sometimes considered to arouse Bacchic enthusiasm and sometimes to cool the brain. The drinking cups at festivals in honor of the god Bacchus were also topped with ivy.

Dionysus worshipers believed that an abundance of ivy in one place was a sure sign of the god's presence. Poets wreathed ivy because ivy was also a sacred plant of the god Apollo and the muses . In ancient times it was therefore already grown in gardens, although Pliny the Elder claimed in his writings that this plant harmed masonry and trees and that snakes felt at home under its leaves. Already in antiquity, varieties were known whose leaves were variegated white or yellow .

In Germany, its horticultural use can be documented for the first time in the middle of the 16th century. The Swiss doctor and naturalist Conrad Gessner , who created a list of garden plants in Germany, counted ivy among the garden plants in 1561. Garden books that were published towards the end of the 17th century also mentioned varieties with variegated leaves for the first time since ancient times. The gardens of the baroque and renaissance , however, offered little space for the rampant ivy. The ivy only became more popular as a garden plant when spacious landscaped parks came into fashion in the second half of the 18th century. As the popularity of ivy increased, so did the number of varieties. An ivy monograph published in Great Britain by Shirley Hibberd in 1872 already listed more than 200 varieties.

Vegetative propagation

The common ivy is easy to propagate with cuttings in moist soil. Juvenile forms retain their habit and can form flower sprouts under suitable conditions. An ivy plant that has emerged from an adult form through vegetative reproduction retains its upright growth type and can never develop creeping sprouts ( topophysis ).

sorts

Today there are around 400 varieties of ivy with a wide range of leaf shapes and colors. They are usually propagated vegetatively with cuttings. Some forms are hardy in large parts of Europe, other forms only in the warmer areas; some are used as house plants . In horticulture, ivy is valued as a climbing plant and also as a ground cover . Plants propagated from head cuttings of the age forms are suitable as low shrubs, which no longer climb or grow in width, but develop their effect through upright to spherical growth and annual flowering.

Selection of readout forms:

- Hedera helix 'Atropurpurea': This shape has purple colored leaves and grows up to 8 meters high.

- Hedera helix 'Buttercup': This variety is characterized by bright yellow leaves that only occasionally have green spots. It only grows up to a height of 2 meters.

- Hedera helix 'Dentata variegata': This is a variety of the giant-leaved Hedera colchica . Their leaves have a yellow edge. The variety is hardy.

- Hedera helix 'Goldchild': This shape is only about 1 meter high; their leaves have a golden yellow margin.

- Hedera helix 'Hibernica': This is the most famous variety. It has dark green leaves, grows quickly, is hardy, and does well in full shade.

- Hedera helix 'Ivalace': This cultivated form, which can also only grow up to 1 meter high, has dark green, glossy leaves with lobes that are strongly arched towards the edges and with significantly lighter leaf veins.

- Hedera helix 'Marginata elegantissima': The leaves of this variety have a white leaf margin. It grows densely and is suitable for partial shade.

Cultural meaning

symbolism

Marianne Beuchert reports that the first Christians laid the dead on ivy, the unconverted on cypresses . Those who are baptized in Christ are immortal, but those who are not baptized have no hope of resurrection , like the cypress trees that once felled, never grow back. If today tombs are often planted with ivy, this is a mostly unconscious use of the symbol of eternal life. "As in life so in death" is an inscription on some old ivy-wrapped tombstones.

Since ivy cannot exist without snuggling up, it has always been a symbol of friendship and loyalty. Even in ancient times, this evergreen plant was a symbol of loyalty and eternal life, in ancient Greece a bridal couple received an ivy branch as a symbol of everlasting loyalty.

Since ivy was associated with the gods of wine in ancient Egypt ( Osiris ) as well as in Greece ( Dionysus ) and in Rome ( Bacchus ), it was also considered a symbol of cheerfulness, conviviality and friendship.

Eight universities on the east coast of the United States form the so-called Ivy League (literally: "Ivy League"), which includes some of the world's best universities (including Harvard and Yale ). The name may come from the fact that many of these colleges have been around for a long time and have old buildings overgrown with ivy. In addition, it was the custom at some of these universities for ivy to be planted as part of academic ceremonies.

Superstition and customs

In Westphalia , on the third Sunday of Lent, girls brought wreaths of ivy to their neighbors, which were hung over the stove to bring spring into the house.

Ivy is said to have been used as an oracle plant on February 24th ( Matthias name day ). At night the girls danced by torchlight and threw ivy and straw wreaths into the water. They had to try to set a wreath behind their backs . The ivy wreath meant happiness in love, it was supposed to be a wedding that same year. The straw wreath , however, indicated bad luck. Oracle was also used with ivy leaves on St. Andrew's night. Two ivy leaves were thrown into a bowl of water so that they floated on the surface. If the leaves were gathered the next morning, there should be a wedding this year. If they drove separately from each other, then one had to wait even longer.

The peasant rule passed down from Switzerland , according to which the behavior of the fruit of the ivy can be used to infer the thriving of the grapes: If the "clouds" of the plant develop well, this also applies to the grapes of the coming year; on the other hand, if the “berries” fall off over the winter, this indicates a poor wine.

art

As an indication of faithful loyalty and eternal life is the most frequent presentation of ivy leaves on early Christian sarcophagi and catacombs - frescoes to understand. The ivy means that the soul lives when the body is dead too.

history

swell

- Antiquity - late antiquity: Theophrast 4th century BC - Dioscurides 1st century --- Pliny 1st century --- Galen 2nd century --- Pseudo-Apuleius 4th century

- Latin Middle Ages: Hildegard von Bingen 12th century --- Innsbrucker (Prüller) herb book 12th century --- Konrad von Megenberg 14th century --- Michael Puff 15th century --- Herbarius Moguntinus 1484 --- Gart der Gesundheit 1485 --- Hortus sanitatis 1491 --- Hieronymus Brunschwig 1500

- Modern times: Otto Brunfels 1532 --- Hieronymus Bock 1539 --- Leonhart Fuchs 1543 --- Mattioli / Handsch / Camerarius 1586 --- Pierre Pomet 1694 --- Nicolas Lémery 1699/1721 --- Onomatologia medica completa 1755 --- Hecker 1814/15 --- v. Hasselt / Henkel 1862 --- August Husemann / Theodor Husemann 1871

Historical illustrations

Vienna Dioscurides 6th century

Pseudo-Apuleius Kassel 9th century

Herbarius Moguntinus 1484

Garden of Health 1485

Hortus sanitatis 1491

Otto Brunfels 1532

Leonhart Fuchs 1543

Hieronymus Bock 1546

Mattioli / Handsch / Camerarius 1586

literature

- Daniel J. Metcalfe: Hedera helix L. (= Biological Flora of the British Isles. No. 240), In: Journal of Ecology . Volume 93, Issue 3, 2005, pp. 632-648. doi : 10.1111 / j.1365-2745.2005.01021.x (full text online)

- Hartmut Dierschke: On the way of life, spread and current distribution of "Hedera helix", an unusual plant in our flora and vegetation. In: Hoppea. Volume 66, 2005, ISSN 0340-4196 , pp. 187-206.

- Ingo Hetzel, Armin Jagel: Hedera helix - common ivy (Araliaceae). Medicinal plant of the year 2010. In: Yearbook of the Bochum Botanical Association. Volume 2, 2011, pp. 206-214, Online PDF 2.2 MB, accessed on January 28, 2014.

- Georg Wilhelm: Ivy on trees - a problem? What we know about the effects of an extraordinary plant. Bund für Umwelt und Naturschutz Deutschland, Kreisgruppe Region Hannover 2010, online PDF 1.8 MB, accessed on January 28, 2014.

Web links

- Common ivy. In: FloraWeb.de.

- Distribution map for Germany. In: Floraweb .

- Hedera helix L. In: Info Flora , the national data and information center for Swiss flora .

- Distribution in the northern hemisphere according to Eric Hultén

- Medicinal Plant Lexicon - Hedera helix (with biochemical information on active substances)

- Common ivy at giftpflanze.com

- Common ivy - Medicinal Plant of the Year 2010

- Sunblock from nature. The key to improved sunscreens may lie in the fine, adherent roots of ivy. On: Wissenschaft.de of July 21, 2010, accessed on September 8, 2019

- German ivy society V., descriptions of many hundreds of varieties, articles on collections

- Profile at baumkunde.de .

Individual evidence

- ^ Georg August Pritzel , Carl Jessen : The German folk names of plants. New contribution to the German linguistic treasure. Philipp Cohen, Hanover 1882; Reprint in 2 volumes, Amsterdam 1967, p. 177.

- ↑ Robert Emmerich: Ivy is Medicinal Plant of the Year 2010 . Press release from the Julius Maximilians University of Würzburg, November 19, 2009.

- ↑ For use as fodder cf. K.-E. Behave: ivy. In: Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde . Edited by Heinrich Beck u. a. Volume 6: Donar-Þórr - Dugout. Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 1986, ISBN 3-11-010468-7 , p. 455; Schweizerisches Idiotikon , Volume I: A – F. Huber, Frauenfeld 1881–1885, column 1816, article Abheu w ( digitized version ).

- ↑ a b Albert L. Loyd, Rosemarie Lühr, Otto Springer: Etymological Dictionary of Old High German. Volume II: bî - ezzo. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen / Zurich 1998, ISBN 3-525-20768-9 , Sp. 927 f. (ebah) and 939 f. (ebihewi), then Etymological Dictionary of the German Language , 18th ed., arr. by Walther Mitzka, Walter de Gruyter, Berlin 1960, p. 152 and 25th ed., arr. by Elmar Seebold, Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / Boston 2011, ISBN 978-3-11-022364-4 , p. 227 f .; Etymological dictionary of German, 2nd edition, reviewed and supplemented by Wolfgang Pfeifer, Akademie, Berlin 1993, ISBN 3-05-000626-9 , p. 260.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j Melissa A. Waggy, 2010: Hedera helix. In: Fire Effects Information System online from the US Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j Daniel J. Metcalfe: Hedera helix L. In: Journal of Ecology. Volume 93, Issue 3, 2005, pp. 632-648.

- ↑ Root climber at the University of Ulm.

- ↑ a b data sheet at BiolFlor - database of biological-ecological characteristics of the flora of Germany . ( Memento of the original from April 9, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ a b Common ivy. In: FloraWeb.de.

- ↑ Rafaël Govaerts (Ed.): Hedera - World Checklist of Selected Plant Families of the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Last accessed on April 29, 2018.

- ^ Erich Oberdorfer : Plant-sociological excursion flora for Germany and neighboring areas . With the collaboration of Angelika Schwabe and Theo Müller. 8th, heavily revised and expanded edition. Eugen Ulmer, Stuttgart (Hohenheim) 2001, ISBN 3-8001-3131-5 , pp. 692 .

- ↑ Erhard Dörr, Wolfgang Lippert : Flora of the Allgäu and its surroundings. Volume 2, IHW, Eching 2004, ISBN 3-930167-61-1 , p. 260.

- ^ Oregon bans sale of English ivy, butterfly bushes. February 10, 2012, accessed December 9, 2012 .

- ^ Community Invasive Species Management at Stanley Park. May 13, 2013, accessed May 13, 2013 .

- ^ English Ivy. Victoria State Department of Primary Industries , June 3, 2011, accessed December 9, 2012 .

- ^ Clayson Howell: Consolidated list of environmental weeds in New Zealand (= Department of Conservation research & development series. 292). Department of Conservation, Science & Technical Pub., Wellington 2008, ISBN 978-0-478-14413-0 , ( PDF file ( Memento of the original from May 30, 2009 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and still not checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this note .; 284 kB).

- ↑ First publication scanned at biodiversitylibrary.org .

- ^ Hedera helix at Tropicos.org. Missouri Botanical Garden, St. Louis, accessed January 31, 2014.

- ^ Hedera helix in the Germplasm Resources Information Network (GRIN), USDA , ARS , National Genetic Resources Program. National Germplasm Resources Laboratory, Beltsville, Maryland. Retrieved January 31, 2014.

- ^ A b Georg Wilhelm: Ivy on trees - a problem? What we know about the effects of an extraordinary plant, p. 3.

- ^ Georg Wilhelm: Ivy on trees - a problem? What we know about the effects of an extraordinary plant. Pp. 2–3, BUND May 20, 2010: full text PDF.

- ↑ Ingo Hetzel, Armin Jagel: Hedera helix - common ivy (Araliaceae). Medicinal Plant of the Year 2010, pp. 208–209.

- ^ Georg Wilhelm: Ivy on trees - a problem? What we know about the effects of an extraordinary plant, pp. 3–4.

- ↑ Ingo Hetzel, Armin Jagel: Hedera helix - common ivy (Araliaceae). Medicinal Plant of the Year 2010, p. 209.

- ^ Georg Wilhelm: Ivy on trees - a problem? What we know about the effects of an extraordinary plant, pp. 4-5.

- ^ A b Georg Wilhelm: Ivy on trees - a problem? What we know about the effects of an extraordinary plant, pp. 5-6.

- ^ Georg Wilhelm: Ivy on trees - a problem? What we know about the effects of an extraordinary plant, pp. 6-7.

- ^ Georg Wilhelm: Ivy on trees - a problem? What we know about the effects of an extraordinary plant, p. 7.

- ^ Georg Wilhelm: Ivy on trees - a problem? What we know about the effects of an extraordinary plant, pp. 7–8.

- ^ Poisonous plants in Germany. University of Münster, Pharmaceutical Biology ( PDF file ( Memento from 23 August 2007 in the Internet Archive ); 4.1 MB).

- ↑ Entry on ivy. In: Römpp Online . Georg Thieme Verlag, accessed on February 18, 2013.

- ↑ Specialist information Prospan® cough syrup. As of November 2016. Engelhard Arzneimittel GmbH & Co. KG, Niederdorfelden. Approval number: 6385862.00.00 URL: https://www.engelhard.de/fileadmin/pdfs/Summaries/Prospan_Hustensaft.pdf

- ↑ wdr.de of February 25, 2010: Ivy. In: Frauen-heilkraeuter.de October 6, 2013.

- ^ Robert Jütte: Lust without load: History of contraception (= Beck'sche series. 1511). Beck, Munich 2003, ISBN 3-406-49430-7 , p. 61, limited preview in Google book search.

- ^ Otto Brunfels: Contrafayt Kreuterbuch. 1532.

- ↑ Werner Dressendörfer: Late medieval medicine taxes of the Munich city doctor Sigmund Gotzkircher from the Grazer Codex 311. A contribution to the early history of the southern German pharmacy. Königshausen and Neumann, Würzburg 1978 (= Würzburg medical-historical research. Volume 15), p. 228.

- ↑ Hans Zotter : Ancient medicine. The collective medical manuscript Cod. Vindobonensis 93 in Latin and German. Academic printing and Verlagsanstalt, Graz 1980 (= Interpretationes ad codices. Volume 2); 2nd, improved edition, ibid. 1986, ISBN 3-201-01310-2 , pp. 169-171.

- ↑ Use ivy as a biological detergent and washing-up liquid. October 8, 2014, accessed on March 23, 2019 (German).

- ↑ K.-E. Behave: ivy. In: Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde . Edited by Heinrich Beck u. a. Volume 6: Donar-Þórr - Dugout. Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 1986, p. 455.

- ↑ Ilja Ratschinski: Information sheet garden. Climbing plants , Verband Wohneigentum Rheinland e. V., Düsseldorf undated (approx. 2006), p. 7.

- ↑ a b without author: Information on the greening of facades (information sheet ), State Capital Dresden, Environment Agency, Dresden 2006, online PDF 194 kB, accessed on June 19, 2020.

- ↑ a b Markus van Berlo: Church buildings in a green guise - green facades , Nature and Environmental Protection Academy NRW, Recklinghausen 2002, Online PDF 1.2 MB, accessed on January 28, 2014.

- ↑ Ingo Hetzel, Armin Jagel: Hedera helix - common ivy (Araliaceae). Medicinal Plant of the Year 2010, p. 212.

- ↑ Iris Scholl, Margot Zahner, Robert Kull: Facade greening. Building with Nature , Commissioner for Environmental Protection of the City of Winterthur and Stadtgärtnerei Winterthur, undated (approx. 2004), Online PDF 304 kB, accessed on January 28, 2014.

- ↑ Pottorff, L. Plants "Clean" Air Inside Our Homes. Colorado State University & Denver County Extension Master Gardener. 2010.

- ^ Wolverton, BC (1996) How to Grow Fresh Air . New York: Penguin Books.

- ^ Wolverton, BC and JD Wolverton. (1993). Plants and soil microorganisms: removal of formaldehyde, xylene, and ammonia from the indoor environment. Journal of the Mississippi Academy of Sciences 38 (2), 11-15.

- ↑ Leaf extracts against whooping cough - ivy is "Medicinal Plant of the Year 2010"

- ^ The Harvard Crimson. June 3, 1893, accessed December 9, 2012 .

- ^ Ivy Day and Ivy Stones, a Penn Tradition. (No longer available online.) University of Pennsylvania, archived from the original on July 15, 2012 ; accessed on December 9, 2012 . Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Schweizerisches Idiotikon , Volume I, Column 1816, Article Abheu w ( digitized version ).

- ↑ Theophrastus of Eresus : Natural history of the plants . 4th century BC Chr. Edition. Kurt Sprengel . Friedrich Hammerich, Altona 1822, Volume I, p. (Book, chapter) Translation [(digitized)], Volume I, p. 125–128, Book III, chapter 18, section 6–10 (digitized) ; Volume II, pp. 123–124 Explanations (digitized version)

- ↑ Pedanios Dioscurides . 1st century: De Medicinali Materia libri quinque. Translation. Julius Berendes . Pedanius Dioscurides' medicine theory in 5 books. Enke, Stuttgart 1902, p. 254 (Book II, Chapter 210): Kissos (digitized version )

- ↑ Pliny the Elder , 1st century: Naturalis historia book XVI, chapter lxii (§ 144–152): Hedera (digitized version ) ; Translation Külb 1855 (digitized) --- Book XXIV, Chapter xlvii (§ 75–80): Hedera (digitized) ; Translation Külb 1855 (digitized version )

- ↑ Galen , 2nd century De simplicium medicamentorum temperamentis ac facultatibus , Book VII, Chapter X / 29 (based on the Kühn 1826 edition, Volume XII, p. 29) (digitized version)

- ^ Pseudo-Apuleius . First printing: Rome 1481, Chapter 101: Hedera nigra (digitized version )

- ^ Charles Victor Daremberg and Friedrich Anton Reuss (1810–1868). S. Hildegardis Abbatissae Subtilitatum Diversarum Naturarum Creaturarum Libri Novem. Physica , Book I, Chapter 140: Ebich . Migne, Paris 1855. Sp. 1186 (digitized version ) - translation: Marie-Louise Portmann, Stuttgart 1991: Vom Ifeu. The ivy is more cold than warm, and it is useless for humans to eat like weeds. But a person who has jaundice would stew ivy in a bowl of deer tallow or old fat, and he would put that warm on his stomach, and the jaundice would pass into that herb, that is, pigtail that even that person's skin was externally yellowish will appear; and when he has put these herbs on his stomach, as was said before, immediately pound watercress in cold water and strain it through a cloth, and give it to him to drink so cold, and the jaundice will be driven out and cured.

- ↑ Innsbruck (Prüller) herb book , 12th century .: . Friedrich Wilhelm (Ed.): Monuments of German prose of the 11th and 12th centuries . Munich 1914/16. Department A: Text, pp. 44/45; Section B: Commentary, p. 111. Text: Ebom iſt gŏt wr the drop if he drinks the hole. Translation: Ivy is good for a stroke if you drink the juice.

- ^ Konrad von Megenberg , 14th century: Book of nature. Output. Franz Pfeiffer . Aue, Stuttgart 1861, p. 321 (IVa / 15): Epaum (digitized version )

- ↑ Michael Puff : Booklet of the burnt-out waters . 15th century. Print Augsburg (Johannes Bämler) 1478 (digitalisat) --- Cpg 558 , Northern Bavaria, around 1470 - 1485, sheet 26r: (digitalisat) Epich water is good for those who have the stain it drives it outside and raÿnnigz dÿ dermer and the bubbles and it is not good for women who it drives away the gepurt likes to vnd verfurt the seeds and does harm to women: - --- Cpg 545 Nuremberg (?) 1474, sheet 116v: (digitized) Eppich water for the stone Item eppich water is good for the men for the stone and cleans the derm and the ploss and it is the frawen harm wan it harm yn and lures the seeds

- ↑ Herbarius Moguntinus , Mainz 1484, Part I, Chapter 60: Edera arborea (digitized version )

- ↑ Gart der Gesundheit . Mainz 1485, chapter 163: Edera arborea. Yfen or ebich (digitized version )

- ↑ Hortus sanitatis 1491, Mainz 1491, Part I, Chapter 162: Edera arborea (digitized version )

- ↑ Hieronymus Brunschwig : Small distilling book , Strasbourg 1500, sheet 45v: Ebbey (digitized version )

- ^ Otto Brunfels : Contrafayt Kreüterbůch . Johann Schott, Strasbourg 1532, p. 152 (digitized version)

- ↑ Hieronymus Bock : New Kreütter Bůch . Wendel Rihel, Strasbourg 1539, part II, chapter 86 (digitized version)

- ^ Leonhart Fuchs : New Kreütterbuch… Michael Isingrin, Basel 1543, chapter 160 (digitized version)

- ^ Pietro Andrea Mattioli : Commentarii, in libros sex Pedacii Dioscoridis Anazarbei, de medica materia. Translation by Georg Handsch, edited by Joachim Camerarius the Younger , Johan Feyerabend, Franckfurt am Mayn 1586, sheet 204r– 205v: Ephew (digitized)

- ↑ Pierre Pomet : Histoire générale des drogues, traitant des plantes, des animaux, & des mineraux; ouvrage enrichy de plus de quatre cent figures en taille-douce tirées d'aprés nature; avec un discours qui explique leurs differens noms, les pays d'où elles viennent, la maniere de connoître les veritables d'avec les falsifiées, & leurs proprietez, où l'on découvre l'erreur des anciens & des modern ... par le sieur Pierre Pomet .... Jean-Baptiste Loyson & Augustin Pillon Paris 1694, p. 264: Gomme Ederae (digitized version )

- ↑ Nicolas Lémery : Dictionnaire universel des drogues simples. , Paris 1699, pp. 343-344: Hedera (digitized version ) ; Translation. Complete material lexicon. Initially drafted in French, but now after the third edition, which has been enlarged by a large [...] edition, translated into high German / By Christoph Friedrich Richtern, [...]. Leipzig: Johann Friedrich Braun, 1721, Sp. 518: Hedera (digitized version)

- ↑ Albrecht von Haller (editor): Onomatologia medica completa or Medicinisches Lexicon which explains all names and artificial words which are peculiar to the science of medicine and the art of pharmacy clearly and completely [...]. Gaumische Handlung, Ulm / Frankfurt am Main / Leipzig 1755, Sp. 749: Hedera arborea (digitized version )

- ↑ August Friedrich Hecker 's practical medicine theory. Revised and enriched with the latest discoveries by a practicing doctor . Camesius, Vienna, Volume II 1815, 164: Gummi resina Hederae. Epheus gum resin (digitized version )

- ↑ Alexander Willem Michiel van Hasselt . JB Henkel (translator): Handbook of poison theory for chemists, doctors, pharmacists and court officials . Vieweg, Braunschweig 1862, part I General poison theory and the poisons of the plant kingdom , p. 483 (digitized version )

- ↑ August Husemann / Theodor Husemann : The plant substances in chemical, physiological, pharmacological and toxicological terms. For doctors, pharmacists, chemists and pharmacologists. Springer, Berlin 1871, p. 255: Hederin (digitized version ) ; P. 810: hederic acid, hederagerbic acid (digital copy ) ; P. 1127: Epheuharz (digitized version )