Dionysus

Dionysus ( ancient Greek Διόνυσος , Latinized Dionysus ) is the god of wine, joy, grapes, fertility, madness and ecstasy (compare the Dionysia ) in the Greek world of gods . The Greeks and Romans also called him Bromios (" noise "), Bacchus ("caller") or Bakchos because of the noise that his entourage made . Dionysus has often been equated with Iakchos and is the youngest of the great Greek gods. In literature and poetry, he is often called Lysios and as Lyaeus called ( "the Sorgenbrecher"), but also as Anthroporrhaistes (Menschenzerschmetterer).

mythology

Dionysus' birth and childhood

Dionysus' father is Zeus . As his son Dionysus also bore the name Sabazios ( saba - zios : son of Zeus ). The mother named Demeter , Io (both corn goddesses), Persephone (an underworld and harvest goddess) and Lethe ( forgetting , a river in Hades, the underworld) and a mortal named Semele (see thigh birth ).

According to the most famous story, Dionysus is the son of Zeus and Semele. In human form, Zeus had a secret love affair with Semele, the daughter of King Kadmos of Thebes . It is said that the jealous Hera , in disguise, persuaded Semele to ask Zeus as a proof of love to show her in his true form. Zeus then showed himself to her as lightning and burned her. Since she was already pregnant with Dionysus, Zeus had her child with him. He made a deep wound and sewed the unripe fruit into his own thigh. After three months he opened it again and brought out Dionysus; he is therefore called "the twice born". With this second birth by Zeus his divinity and immortality are established. According to this myth, Dionysus is the only immortal god with a human mother.

Dionysus and Ino

In Laconia there is a myth that Semele carried out Dionysus in secret and gave birth to Kadmos in the palace of her father. When he discovered the secrecy and shame of the house, he locked mother and son in a box and had them thrown into the sea. But the box was driven to the coast of Laconia. Semele was recovered dead and solemnly buried. However, her son was still alive. He was looked after and raised by her sister Ino (Greek Ίνώ) as a wet nurse. Ino's loyalty to her dead sister was badly rewarded: Hera tracked down Dionysus' new whereabouts and punished Ino and her husband Athamas with madness. In this condition Athamas killed one of his sons, but Ino jumped into the sea with her other son to kill themselves. Ino, however, is called Leukothea, "white goddess", after her death. Wilamowitz writes that she was an ancient goddess before she was made one of the daughters of Kadmos, and Kerényi calls her "a Dionysian primal woman, nurse of God and divine maenad ".

Dionysus as the rebirth of Zagreus

The identification of Dionysus as Zagreus as early as Greek epochs is controversial in research, since Christian sources explicitly document a Dionysus-Zagreus ( Firmicus Maternus ). Zeus approached his daughter, the underworld goddess Persephone , in a cave as a snake, which has been passed down to us primarily as the story of the Orphics . Your child was known as Zagreus , the "great hunter", which is also known as Zeus himself as an underworld god, especially in Crete. However, Hades , Persephone's husband, was also named as the father, who was also called Zeus Katachthonios ("subterranean Zeus"). Dionysus, too, was called the "subterranean" son of Persephone Chthonios .

Zeus loved his son, which aroused Hera's jealousy. She urged the titans to kill Dionysus. He was surprised while playing and torn into seven pieces by the Titans, boiled in a cauldron on a tripod, roasted over the fire and devoured. But the horns of the roasted child remind us that it is a sacrificed kid or calf, whose sufferings corresponded to those of the god.

Zeus punished this act by destroying the titans with lightning. The human race is said to have arisen from the mixture of the ashes of Zagreus and those of the Titans . Man contained divine and titanic elements. According to the Orphics, through purification and initiations one could lose the titanic element and become a backchos .

In addition to this orphic, there are various other sequels to the story of the slaying of Dionysus by the Titans:

Zeus collected the limbs and handed them over to Apollo , who buried them in Delphi . There his resurrection was celebrated annually in the winter absence of Apollo .

According to another story, the first vine arose from the ashes of the burned limbs of Zagreus.

It was also reported that Rhea collected the limbs cooked in the cauldron and put them back together. Zagreus had returned to life and was returned to Persephone. The difference between these two stories is small. In another version it is reported that the boiled limbs of the first Dionysus, the son of Demeter , came into the earth, where the sprouted earth would have torn and boiled him; Demeter, however, had gathered the limbs, and that meant the origin of the vine. It is later reported that there was a vine on the spot where Semele died.

It was said that Athena put aside only the heart of Dionysus . Zeus gave this heart to Semele to eat or in a drink, so that he was received again. It is also said that Zeus entrusted the kradiaios Dionysus' to the goddess Hipta so that she could wear it on her head. Hipta, on the other hand, is an Asian Minor name of the great mother Rhea, and kradiaios can be derived from both kradia (kardia) "heart" and krade "fig tree". In truth, it was another part of the body that a goddess hid in a covered basket, namely the phallos .

Birthplace Nysa, mythological and geographical aspects

Dionysus may have been born on Mount Nysa . He was still a thorn in the side of his old enemy Hera. When the danger from Hera was particularly great once in his childhood, Zeus transformed Dionysus into a kid and handed him over to the nymphs of Mount Nysa, who tended the child in a cave and fed it with honey. His wet nurse was initially Ino , Semele's sister . Dionysus was disguised as a girl. Another nymph was called Makris and also had the name Nysa . Another nymph was called Nysis oros , "Nysaberg".

Nysa (Greek Νύσα) is a name that can be ascribed to numerous locations, but can only be proven at a later time - namely after various mountains and places were named after the birthplace of Dionysus. In the Byzantine Lexicon of Hesychios of Alexandria from the 5th century BC We find a list of the following localizations, which ancient authors call the place where Nysa is said to have been: Arabia , Ethiopia , Egypt , on the Red Sea, Thrace , Thessaly , Cilicia , India , Libya , Lydia , Macedonia , Naxos , in the area of Pangaios (mythical island in southern Arabia) and ultimately Syria . According to legend, there was once a city called Nysa on Mount Meros, where a Dionysus cult also existed . Since Meros means thigh in Greek , according to Strabon (XV, 1. §. 8), Curtius (VIII, 10) and Arrian (Hist. Indicae) the legend went that Zeus brought his son in his thigh to where Semele took him then gave birth. Ivy and the vine , important symbols of Dionysus, are native to this mountain of Meros .

Madness, wandering and purification of Dionysus

Dionysus and Thetis

Zeus once brought Dionysus to the wooded Nysa and entrusted him to the nymphs, who were supposed to cherish and care for him. They did the same in their cave, where they fed him with milk and honey and looked after him well. But the nymphs had an enemy in the Thracian king Lycurgus. One day he ruthlessly pursued the wet nurses of Dionysus and drove them with whips so that they fled away in all directions, screeching loudly. Dionysus had no choice but to jump into the sea. There Thetis , the silver-footed, took him and offered him shelter in the depths of the ocean until he had grown into a youth. Thetis is practically identical to the ancient goddess Tethys , wife of Oceanus and mistress of the sea, who is sometimes called her grandmother. But Dionysus had not forgotten the misdeeds of Lycurgus. He beat him madly and thus avenged the innocent nymphs. Lycurgus madly murdered all his relatives and friends before a miserable death himself.

Dionysus and Amaltheia

According to another version, it was the nymph Amaltheia who fed and raised Dionysus. Rhea once had a son from Kronos who devoured all of her children. This time, however, she hid her son from him in a cave, where she met nymphs who played by the stream and heard the child crying. The nymph named Ver (Vega) picked up the child and turned Amaltheia into a goat so that her son could be looked after. The goat is an important symbol of Dionysus. Amaltheia (Greek Άμάλθεια), whose name means Divine White Goat , had a cornucopia of good gifts, and therefore it is easy to recognize in her an original form of the Great Mother, who was then downgraded to a nymph.

Hera beats Dionysus with madness

Kerényi writes that Dionysus was raised by his mother in her "Cybelean cave". According to this etymological connection, the goddess Cybele , the Phrygian form of the Greek Rhea , is the mother and tutor of Dionysus. Together with Demeter , the same goddess is also considered the protective goddess of the Dionysus religion.

According to various myths, Hera struck the young god with madness, and he then wandered through numerous countries in Africa and Asia. One version tells: after Dionysus had been maddened by Hera as a child and he had wandered through Egypt and Syria in this state , he came to Cybela in Phrygia . There Cybele alias Rhea purified him and thus healed him. Cybele is also the goddess who Euripides imagines as the partner of Dionysus: Blessed is he who is in high happiness / Knows consecration to the gods ... / Who adheres to the great / Mother Cybele high custom, / With the wild swing of Thyrsos / Himself - the head is crowned with eppich - dedicates / entirely to the service of Dionysus .

Dionysus and Ariadne

Ariadne is the wife and helper of Dionysus. She was originally a mortal woman before Dionysus - like his mother Semele - raised her to be a goddess. And this is how it happened: In a cave on Crete lived a bull monster, which was called the Minotaur . The hero Theseus offered to defeat it, and to do so he received a sword and a ball of thread from Ariadne. In return he had to promise her that he would bring her home as a bride on his return to Athens . Theseus defeats the Minotaur with Ariadne's sword and finds his way out of the labyrinth with her thread. He keeps his promise and starts the journey home with Ariadne. However, when they make a stop on the island of Naxos , he leaves her alone while she sleeps. This is said to have happened on the instructions of the goddess Athena . According to much older versions, Ariadne was even dead, because Artemis killed her at the request of Dionysus. Now Dionysus appears on the scene and takes Ariadne as his bride. There are different variants of this: It is said that Dionysus appeared to Theseus in a dream and announced to him that the girl was his own. In another version, Dionysus appears as the savior and groom of the girl on Naxos. There are even stories in which he made her his wife in Crete. Dionysus gave Ariadne a wreath adorned with precious stones, a gift he had once received from Aphrodite , and it is also said that this wreath shone for Theseus in the cave and that the thread was not responsible for his way out. In the end, Ariadne goes to heaven with Dionysus in his chariot and becomes a goddess.

Myths of the departure of Dionysus

To mark Dionysus' farewell from the earthly world, Otto lists the following four versions:

- At the Agrionic Festival in Chaeronea he fled to the Muses and stayed hidden with them so as not to return from them.

- According to the Argives, he sank in Lake Lerna , which symbolizes the fall into the underworld.

- Perseus triumphed over him and threw him into the lake of Lerna.

- According to an Orphic hymn, he rests in the house of Persephone for two years after his departure and thus returns to the one from which he once came.

progeny

Representations

Mostly Dionysus is represented with ivy or vine tendrils and grapes. Its attributes are the thyrsos , which is crowned with ivy and vines, and the kantharos (drinking vessel for wine). He is also often depicted with panther or tiger skins .

Attributions

Usually he was in triumphant company with the Silene and satyrs (such as Ampelus ), who embody the fertility of untamed nature. He was mainly worshiped by women, the maenads . They were wreathed with ivy, wrapped in deer, deer or fox skins and carried torches and thyrsoy . The name bassarids (alternative to maenads) comes from the fox skins , because bassaros means fox . Other proper names related to the fox are Dionysos Bassaros, fox-like Dionysus or Bassareus, the fox god , a Thracian allonym and epithet for Dionysus, also the name under which he was worshiped in Lydia. In their orgiastic rites (see Dionysus cult ) wild animals were torn and eaten and “free love” between the sexes was enjoyed. They danced to the accompaniment of flutes, timpani and tambourines. The earliest maenads wore tame serpents wound around their arms and the god appeared to them as a bull. There are numerous ancient representations of Dionysus and his entourage, for example on the Roman Campana reliefs . In his capacity as god of joy, the theater was invented by the Dionysia in Athens and the prototype of the theater was built, the Dionysus Theater in Athens.

As solver (Lysios, Lyaios) he unleashed the people who freed them from worries and let down walls.

His animal form was the bull , which connects him to his father Zeus .

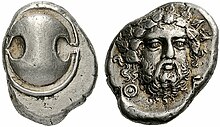

In human form, Dionysus was ritually represented as a bearded mask, which hangs on a pole or a pillar, underneath a long robe.

He is often equated with the Iakchos called in the Eleusinian Mysteries , the divine child .

During Apollon's winter absence , Dionysus oversaw the oracle at Delphi .

Later in Rome the Dionysia was celebrated as the Bacchanalia , as Dionysus is called Bacchus in Latin .

Reception and artistic representations in modern times

The Dionysus myth has inspired numerous artists such as Caravaggio , Allart van Everdingen , Benvenuto Tisi Garofalo , Guido Reni , Rembrandt and Rubens since the Renaissance .

In his work The Birth of Tragedy from the Spirit of Music, Friedrich Nietzsche contrasts the intoxicatingly vital Dionysian and the aesthetically contemplative Apollonian as the two basic principles of human existence.

The Dresden Semperoper is also dedicated to God. On the exedra of the main facade he leads Ariadne to the gods on a quadriga drawn by panthers. The larger than life bronze monument was made by Johannes Schilling .

In the second season of True Blood , the maenad Maryann tries to summon the god Dionysus. In his novel Der Narr , the author Stefan Papp takes the Dionysus myth as a leitmotif in order to interpret the aspect of “intoxicating madness” as an opportunity for self-knowledge.

interpretation

In the 19th century, Johann Jakob Bachofen considered Dionysus to be a god from the time of hetarianism (constructed by him), i.e. before the introduction of rulership structures and marriage, and attributed him to the pre-Greek Pelasgians who, in his opinion, were organized according to maternal rights . After the triumph of patriarchy - so Bachofen - the Pelasgic religion lived on in the mystery cults . Walter F. Otto saw him as the embodiment of the shock experience of childbirth, which frightens in its wildness and shows the inner essence of the Dionysian madness.

Today there seems to be a consensus about the origin of the Chr. Dionysus cults also proven to rule in Thrace in Greece , but the figure is older and shows parallels to the Egyptian gods. It is interpreted in many ways, which corresponds to its inner turmoil. As a son, companion, lover, hero or demon of the earth (embodied by Demeter, Rhea or Semele) as well as Persephone and Hecate and due to his relationships with many other female deities, Dionysus can be regarded as the "god of goddesses" or god of women. This is also supported by its relationship to the water of life, which is mythologically closely linked to the even "stronger" wine.

Originally, the Greek gods did not know death and dying, the journey to the underworld and the return as a resurrection from death, but the Egyptians did. In the form of the story of Isis and Osiris , we have a tradition that is essentially identical to that of Rhea and Dionysus. Like Osiris, Dionysus was dismembered, and like Osiris, he lives on. Herodotus already identified Dionysus with Osiris. In the eternal dying and becoming of nature its fate repeats itself; This is celebrated in unleashed dance and intoxication. The myth becomes the ultimate guarantor of the natural order of life: when the water of the Nile dwindled threateningly, the lamentation of Isis was celebrated; her tears should swell the Nile again. In a riddle epigram, a Greek poet asks how long it would take to fill a large cup that the Nile would fill in one, Achelous in two, and Dionysus in three days alone. The two sacred rivers are nutrient rivers, and Dionysus appears in this context as a deity that gives life and fertility through moisture. The Apis bull is an embodiment of Osiris, to whom sacrifices are made as well as the bull-headed Dionysus in Greater Greece .

Nickname

Dionysus is one of the Greek deities with the most surnames ( epithets ) and is therefore rightly called Polyônomos ("the many-named"). Adam P. Forrest's list of Names and Epithets of Lord Dionysus includes around 110 epithets, and Benjamin Hederich's Thorough Mythological Lexicon from 1770 lists at least 75 epithets. In addition to Forrest's list, a number of other English-language lists are available online.

This led to the fact that in the Hellenistic period he offered himself as an object of projection and identification for many local deities and merged with Osiris to form Sarapis . The following list contains the nicknames mentioned in this article and elsewhere on Wikipedia :

- Dionysus Bakchos or Bacchus - Dionysus, the caller

- Dionysus Bassaros or Bassareus - Dionysus, the fox-like

- Dionysus Bromios - Dionysus, the Noisy

- Dionysus Chtonios - Dionysus, the subterranean

- Dionysos Eleuthereus - Dionysus from Eleutherai

- Dionysus Lysios, Lyaios or Lyäus - Dionysus, the worry breaker

- Dionysos Melanaigis - Dionysus with the black fur

- Dionysus Polyônomos - Dionysus, the many-named

- Asterios - Dionysus, the star (invocation as a boy and child of the mysteries)

swell

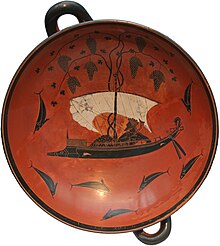

Probably the earliest literary representation can be found in the collection of Homeric Hymns . There three hymns are dedicated to Dionysus and deal in particular with aspects of birth (Hymnos 1), the episode with the Tyrrhenian sailors (Hymnos 7) and the ritual ecstasy (Hymnos 26).

The Greek tragedian Aeschylus processed the myths about Dionysus in at least nine of his works: However, these include ( Semele / Hydrophoroi , Trophoi , Bakchai , Xantriai , Pentheus , Edonoi , Lykourgos , Neaniskoi , Bassarai ) all to Aeschylus' lost tragedies.

The Bakchai of Euripides from the year 406 BC is different . BC, which was the only surviving tragedy for the Dionysus myth that had a decisive influence on the image of the cult and its significant features in classical times.

Another important preserved source is the library of Apollodorus from the 1st century AD. Summarizing representations from the same as from earlier times can be found in Ovid's Metamorphoses and as a hymn to Dionysus in Seneca's tragedy Oedipus . In the 5th century AD, Nonnos of Panopolis created the Dionysiacs, the longest extant epic of antiquity to this day. After seven books describing the prehistory of Dionysus 'birth, books 8–12 deal with the birth and youth of God, books 13–24 deal with Dionysus' procession to India, books 24–40 his fights there and books 41–48 his return to Europe. The Dionysiacs differ in some points from the library of Apollodorus .

literature

- Alberto Bernabé Pajares (Ed.): Redefining Dionysus. Walter de Gruyter, Berlin 2013.

- Ulrich van Loyen, Gerhard Regn: Dionysus. In: Maria Moog-Grünewald (Ed.): Mythenrezeption. The ancient mythology in literature, music and art from the beginnings to the present (= Der Neue Pauly . Supplements. Volume 5). Metzler, Stuttgart / Weimar 2008, ISBN 978-3-476-02032-1 , pp. 230–246.

- Renate Schlesier , Agnes Schwarzmaier (ed.): Dionysos. Transformation and ecstasy . Schnell + Steiner, Regensburg 2008, ISBN 978-3-7954-2115-1 (for the exhibition Dionysus - Metamorphosis and Ecstasy in the Antique Collection of the Pergamon Museum , November 5, 2008– June 21, 2009).

- Detlef Ziegler: Dionysus in the Acts of the Apostles - an intertextual reading . Lit, Münster 2008, ISBN 978-3-8258-1496-0 .

- Max L. Baeumer: Dionysus and the Dionysian in ancient and German literature . Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 2006, ISBN 3-534-19074-2 .

- Richard Seaford: Dionysus. Routledge, London / New York 2006, ISBN 0-415-32488-2 (English, a very useful introduction).

- Hans-Ulrich Cain: Dionysus - “The curls long, half a woman? ... ”(Euripides) . Edited by the Museum for Casts of Classical Paintings in Munich. Munich 1997, ISBN 3-9805981-0-1 (for the special exhibition from November 10, 1997 to February 28, 1998).

- Thomas H. Carpenter: Dionysian Imagery in Fifth-Century Athens . Oxford 1997.

- R. Osborne: The Extasy and the Tragedy. Varieties of Religious Experience in Art, Drama, and Society. In: C. Pelling (Ed.): Greek Tragedy and the Historian . 1997, pp. 187-211.

- Thomas H. Carpenter, Christopher A. Faraone (eds.): Masks of Dionysus . Cornell University Press, Ithaca / London 1993, ISBN 0-8014-2779-7 (collection of essays that give a good overview of the current state of research, extensive bibliography).

- Anne Ley: Dionysus. In: The New Pauly (DNP). Volume 3, Metzler, Stuttgart 1997, ISBN 3-476-01473-8 , Sp. 651-664.

- BF Meyer: The raging god. On the psychology of Dionysus and the Dionysian in myth and literature. In: Antiquity and the Occident. 40, 1994, pp. 31-58.

- Anton F. Harald Bierl : Dionysus and the Greek tragedy: political and "metatheatrical" aspects in the text (= Classica Monacensia Volume 1), Narr, Tübingen 1991, ISBN 3-8233-4861-2 (dissertation University of Munich 1990, XI, 298 Pages, 23 cm), examines Dionysus' appearance in the classical tragedies.

- Marion Giebel : The Secret of the Mysteries. Ancient cults in Greece, Rome and Egypt . Artemis, Zurich / Munich 1990, ISBN 3-7608-1027-6 (new edition: Patmos, Düsseldorf / Zurich 2003, ISBN 3-491-69106-0 ), pp. 55-88.

- John J. Winkler , Froma I. Zeitlin (Ed.): Nothing to Do with Dionysos? Athenian Drama and its Social Context . 1990.

- HA Shapiro: Art and Cult under the Tyrants in Athens . Mainz 1989, pp. 84-100.

- Walter Burkert : Ancient Mystery Cults . Harvard University Press, Cambridge 1987 (German edition: Ancient Mysteries: Functions and Content. 4th Edition. Beck, Munich 2003, ISBN 3-406-34259-0 ).

- Thomas H. Carpenter: Dionysian Imagery in Archaic Greek Art . Oxford 1986.

- Friedrich Wilhelm Hamdorf: Dionysus Bacchus. Cult and changes of the wine god . 1986.

- Bernhard Gallistl: The Zagreus myth in Euripides. In: Würzburg yearbooks. 7, 1981, pp. 235-252.

- Albert Henrichs : Greek Maenadism from Olympias to Messalina. In: Harvard Studies in Classical Philology. 82, 1978, pp. 121-160 ( JSTOR 311024 ).

- Marcel Detienne : Dionysus mis á mort. Paris 1977 (German as: Dionysos. Divine wildness . Dtv, Munich 1995, ISBN 3-593-34728-8 ).

- Karl Kerényi : Dionysus: archetype of indestructible life . Langen Müller, Munich / Vienna 1976 (new edition: Klett-Cotta, Stuttgart 1994, ISBN 3-608-91686-5 ).

- Friedrich Matz : ΔΙΟΝΥΣΙΑΚΗ · ΤΕΛΕΤΗ. Archaeological research on the Dionysus cult in Hellenistic and Roman times (= treatises of the humanities and social sciences class of the Academy of Sciences and Literature in Mainz. 1963, no. 14).

- Friedrich Matz : The Dionysian sarcophagi . 4 volumes. Gebr. Mann, Berlin 1968–1975.

- Martin Persson Nilsson : The Dionysiac Mysteries of the Hellenistic and Roman Age . Gleerup, Lund 1957.

- Karl Kerényi: The Gods and Human Stories. Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, Darmstadt 1951 ( The Mythology of the Greeks , Volume 1; 19th edition, Deutscher Taschenbuch-Verlag, Munich 1998, ISBN 3-423-30030-2 ).

- Martin Persson Nilsson: Greek Faith . Bern 1950.

- Eric Robertson Dodds (Ed.): Euripides: Bacchae . Clarendon, Oxford 1944 (1989 new edition, ISBN 0-19-872125-0 ; Dodds' introduction and commentary are particularly important and influential).

- Walter F. Otto : Dionysus - Myth and Cult . Klostermann, Frankfurt am Main 1933.

- Erwin Rohde : Psyche. Soul cult and belief in immortality of the Greeks . Mohr, Freiburg in Breisgau 1894 (reprint: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, Darmstadt 1991).

- Friedrich Adolf Voigt : Dionysus . In: Wilhelm Heinrich Roscher (Hrsg.): Detailed lexicon of Greek and Roman mythology . Volume 1,1, Leipzig 1886, Sp. 1029-1089 ( digitized version ).

Web links

- Aaron J. Atsma: Dionysus. In: The Theoi Project: Greek Mythology. 2011, accessed September 1, 2013 (English, translated original sources and images).

- Image archive: Gods & Myths: Bacchus. In: Warburg Institute Iconographic Database . University of London, 2013, accessed September 1, 2013 (English, about 2000 photos of representations of Dionysus).

- Adam P. Forrest: Names and Epithets of Lord Dionysus. In: The Hermetic Fellowship Website. March 20, 2003, accessed on September 1, 2013 (English, listing of all names of Dionysus).

- John Boardman : The Triumph of Dionysus. In: Bible Lands e - review 2013, L 1, (online) .

Remarks

- ^ Karl Kerényi: The stories of gods and mankind. Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 1951, p. 256.

- ^ Karl Kerényi: The stories of gods and mankind. Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 1951, p. 257.

- ↑ Ulrich von Wilamowitz-Moellendorff: The faith of the Hellenes . Volume 1, Berlin 1931, p. 407 f.

- ↑ Karl Kerényi: Dionysus: archetype of indestructible life . Klett-Cotta, Stuttgart 1994, ISBN 3-608-91686-5 , p. 154.

- ^ Karl Kerényi: The stories of gods and mankind. Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 1951, p. 245.

- ^ Karl Kerényi: The stories of gods and mankind. Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 1951, p. 243.

- ^ A b c Karl Kerényi: The stories of gods and mankind. Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 1951, p. 247.

- ^ A b Karl Kerényi: The stories of gods and mankind. Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 1951, p. 247 f.

- ^ Wilhelm Vollmer: Complete dictionary of the mythology of all peoples. A compact compilation of the most worth knowing from the myths and gods of the peoples of the old and new world . Stuttgart 1851, pp. 179, 778.

- ↑ Karl Kerényi: Dionysus: archetype of indestructible life . Klett-Cotta, Stuttgart 1994, ISBN 3-608-91686-5 , p. 130.

- ^ C. Karl Barth: Hertha. And about the religion of the world mother in old Germany. Augsburg 1828, p. 125.

- ↑ Julius Braun : Natural history of the legend. Return of all religious ideas, legends and systems to their common family tree and their last root , Volume 1, Munich 1864. 1864, p. 122.

- ^ Johann Nepomuk Uschold: entrance hall to Greek history and mythology. Part 1, Stuttgart / Tübingen 1838, pp. 146–147.

- ↑ Karl Philipp Moritz: Gods teaching or mythological poems of the ancients. Berlin 1861, p. 132 f.

- ↑ Reinhold Merkelbach: The shepherds of Dionysus. The Dionysus Mysteries of the Roman Empire and the Bucolic Roman of Longus. Stuttgart 1988, p. 45.

- ↑ Johann Adam Hartung: The religion and mythology of the Greeks. Part 2: The primordial beings or the kingdom of Kronos , Leipzig 1865, p. 136 f.

- ↑ Karl Kerényi: Dionysus: archetype of indestructible life . Klett-Cotta, Stuttgart 1994, ISBN 3-608-91686-5 , p. 51.

- ↑ Karl Kerényi: Dionysus: archetype of indestructible life . Klett-Cotta, Stuttgart 1994, ISBN 3-608-91686-5 , p. 103.

- ^ Julius Leopold Klein : History of Drama . Volume 2: The Greek and Roman Drama . 1865, p. 41 f.

- ↑ Euripides: The Bacchae. 77.

- ^ Karl Kerényi: The stories of gods and mankind. Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 1951, p. 262 f.

- ^ Karl Kerényi: The stories of gods and mankind. Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 1951, p. 263.

- ^ Walter F. Otto : Dionysus - Myth and Cult . Klostermann, Frankfurt am Main 1933, p. 74 f.

- ^ Klaus Mailahn: The Fox in Faith and Myth Lit, Münster 2006, ISBN 3-8258-9483-5 , pp. 335–347.

- ^ Names of Dionysus

- ↑ Stefan Papp: The Fool. Lucifer-Verlag, Vienna 2012, ISBN 978-3-943408-28-7 .

- ↑ Johann Jakob Bachofen : The mother right: an investigation into the gynecocracy of the old world according to its religious and legal nature . Stuttgart 1861.

- ^ Walter F. Otto: Dionysus. Myth and Cult . Klostermann, Frankfurt am Main 1933, p. 133.

- ↑ Klaus Mailahn: Dionysus, god of the goddesses. Munich 2011, p. 11 f.

- ^ Franz Streber: About the bull with the human face on the coins of southern Italy and Sicily. In: Abhandlungen der Bayerische Akademie der Wissenschaften, Philosophisch-Historische Klasse, Volume 2. Verlag der Bayerischen Akademie der Wissenschaften on commission from the CH Beck'sche publishing house, 1837, p. 547 ff.

- ↑ Different spellings of the same epithet were not counted. - See: Names and Epithets of Lord Dionysus .

- ↑ See Hedrich 1770 .

- ↑ E.g .: Archived copy ( memento of October 10, 2011 in the Internet Archive ), theoi.com and hellenicgods.org , the latter with detailed comments.

- ^ Karl Kerényi, The Mythology of the Greeks , Volume I, ISBN 3-423-01345-1 , p. 211.

- ↑ a b c Aaron J. Atsma: Dionysus . In: The Theoi Project. Greek Mythology. (English), accessed on May 2, 2011.

- ↑ Metamorphosen 3, pp. 516-733 and 4, pp. 1-41, 389-415.