Theater of ancient Greece

The history of ancient Greek theater spans nearly a thousand years. Even the preliminary forms were of a cultic nature and consisted of choral songs ( dithyrambs ) and dances, which were increasingly combined with action elements. The cult of Dionysus in particular was essential for the development of the drama . The theater of ancient Greece reached its peak in the 5th century BC. BC with the plays of the three great tragedians Aeschylus , Sophocles and Euripides and the plays of the Old Comedy , especially of Kratinos and Aristophanes . While the cultic purpose faded into the background, the theater fulfilled an important function for the development of Attic democracy : it stood for self-assurance, representation and a demonstration of power by the polis society. The ancient Greek theater was a theater of free citizens of both sexes: attending the performances was a democratic right and a religious and moral duty at the same time. Due to falling audience numbers, the Athenian state led in the 4th century BC. A compensation for the loss of earnings while attending the performances.

After the decline of Attic democracy , the Roman state integrated the forms of the Greek theater into its festivities and developed the theater into a mass-effective instrument for entertainment and the representation of political power.

The development of the entire occidental theater culture goes back to the theater of ancient Greece and is decisive through the traditional drama as well as through theater aesthetic elements (such as the choir and the use of masks) and above all through the reflection of the social role of theater been coined.

Emergence

In the 20th century, the archaeologists Luigi Pernier and Carlo Anti took the view that the display stairs of the palace complexes of Crete were already a pre-form of ancient theater buildings and were used as rows of seats for spectators. Hans Peter Isler contradicts this , stating that the function of these low stairs, on which sitting would not have been possible anyway, has still not been clarified.

Isler dates the beginnings of Greek theater to the later decades of the 6th century BC. BC, based on publications by Gustav Adolf Seeck , Bruno Gentili and Horst-Dieter Blume .

The Dionysia and the most important part for today's theater, the tragedies , already became a religiously important festival under Peisistratos , but due to the Phylenreform of Kleisthenes all of Attica was involved in the Dionysian festivals. In the beginning there was only one actor who included a choir, who presumably did not sing but occasionally answered the actor. After Athens was destroyed by the Persians, a skené developed for the theatron , and more and more accessories were soon invented. Four pieces were performed each day. Three tragedies were followed by a satyr play as a cheerful, liberating sequel.

The classical heyday of Greek theater ended with the decline of the classical Athens polis and the establishment of the Hellenistic kingdoms .

The characteristics of the Greek theatrical art have been preserved mainly due to the poetics of Aristotle ( 384 to 322 BC ). The influence on European theater is shown on the one hand by the fact that many materials that were used by the classical Greeks later repeatedly aroused interest and were further used, for example by the ancient Roman comedy poets Plautus and Terence . On the other hand, there were also numerous attempts to stimulate a “rebirth” of classical times, always taking into account the prevailing time streams.

construction

The Greek theaters were open-air theaters that were built into a slope, mostly facing north-south.

Beginnings (6th century BC)

Characteristic components of the theater in the 6th century are the orchestra , the actual playground or dance area, a kind of auditorium ( theatron ) and the skené ( which can be translated with a tent or booth ), in which the actors could dress up or change clothes . The text and images described by Arthur Wallace Pickard-Cambridge in his monograph The dramatic festivals of Athens , first published in 1953, show that the audience in the 6th century BC. BC either on slopes or wooden stands.

Classical Age (5th Century BC)

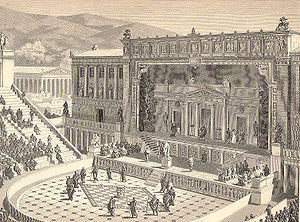

Research on Greek theater practice is confronted with the fact that there are very few documents on the theater of the fifth century BC. BC, which is often called the classical age of the tragedy poets Aeschylus , Sophocles and Euripides . To this day it has not been conclusively clarified whether the orchestra and the auditorium, the so-called theatron, in the Athenian Dionysus Theater of the fifth century BC. BC already had a round shape with a stage building in front of the orchestra (as in the sketch opposite) or whether the orchestra and theatron were rectangular.

The archaeologists Wilhelm Dörpfeld and Emil Reisch describe the Orchestra in their monograph The Greek Theater , published in 1896, as a "round dance floor", but without providing any evidence for this assumption. Ulrich von Wilamowitz-Moellendorf also speaks of a "circular, brick-built dance floor", referring to Dörpfeld's "correspondence by letter ".

Hans Peter Isler calls this assumption "very bold", since the two surviving remains of the Cyclops masonry , which was built in the 5th century BC. At the place of the Dionysostheater, are only slightly curved.

This is also supported by recent findings, which show that the preserved Greek theaters of the fifth century BC. BC all have a rectangular shape or at least have been adapted to the conditions of the building land in such a way that one cannot speak of a circular orchestra. The stone theater of Thorikos , whose rectangular shape dates back to the 4th century BC , is particularly suitable as an object of investigation . Has demonstrably not experienced any architectural change. According to the archaeologist Raimund Merker, this is a sign that all the dramas from this period were designed for a rectangular orchestra.

Also for the fifth century BC are largely certain. The following components:

- Theatron (initially made of wood, later of stone),

- Skené (wooden stage house, hence also "scene"),

- Orchestra , the playing area for choir and actors,

- Parodoi , the two side entrances to the orchestra,

- Ekkyklema , a kind of rolling stage that could be rolled out of the Skené in order to visualize events that happened behind the stage in a tableau,

- Mechane , a crane with which a deus ex machina, for example , could float down onto the stage and intervene in the tragic events.

The sources on actual acting practice are also poor. The origin of the Greek tragedy are the dithyrambs , solemn choral songs in honor of Dionysus , the master of which is Arion of Lesbos . The first tragedy poet was Thespis , who is still remembered today by the name of the theater as the Thespiskarren ; he contrasted the choir with a single solo actor, the protagonist , in the mask of Dionysus. Aeschylus introduced the second actor, the deuteragonist , and Sophocles finally the third, the tritagonist .

The number of actors remained limited to three. If more people appear, then never more than three at the same time, and at least one actor had to change his mask.

The choir consisted of 12 or 15 choir members, moved into the theater after the prologue by the Parodoi and usually stayed in the orchestra for the entire performance.

Only men were allowed to perform as actors and choir members (members of the choir). It was played with masks.

The movements of the choruses and actors, the way they speak, the singing and the music have hardly been handed down. There is a great deal of dispute in research about the extent to which conclusions can be drawn about stage practice from the dramatic texts that have been preserved. Despite a great deal of research interest, very little is basically known about ancient Greek theater.

Basic course of action

- Prologue / exposition

- Einzuglied / Parodos (sung by a choir)

- 1. Epeisodion / rising action

- 1. Standlied / Stasimon (sung by a choir)

- 2. Epeisodion / climax

- 2nd stand song (sung by a choir)

- 3. Epeisodion / Peripetie

- 3rd stand song (sung by a choir)

- 4. Epeisodion / falling action

- 4th stand song (sung by a choir)

- 5. Epeisodion

- 5th stand song (sung by a choir)

- 6. Exodos / disaster

- 6. Closing words (sung by a choir)

Social function

The Greek theater wasn't just for men. Only free citizens could participate (no slaves), but the back rows of seats were reserved for women.

The equipment of the choir and its maintenance were the responsibility of the choir . The choir was an important leiturgy , that is, a private individual's service for the polis community .

The theater was used to entertain the population and, since the beginning of the comedy, also for amusement. Due to its religious character, the visit was socially compulsory, but the honoring of the actors and authors testifies to a further appreciation; because famous participants were honored and fed by the state.

Poets and Works (selection)

tragedies

-

Aeschylus (around 525 to 456 BC ):

- The Persians , Prometheus Chained , The Oresty (Trilogy: Agamemnon , The Donation of the Dead and The Eumenides )

-

Sophocles ( 496 to 406 BC ):

- Aias , Antigone , King Oedipus , Electra

- Euripides ( 480 to 406 BC ):

Comedies

-

Aristophanes (around 445 to around 385 BC ):

- The clouds , the birds , lysistrates , the frogs , the peace

-

Menander ( 342 / 341 bis 291 / 290V Chr.. ):

- Dyskolos (The Difficult / The Curmudgeon), Epitrepontes ( The Arbitral Tribunal )

See also

- Scenography

- List of ancient theaters

- Theater (building) , about the history of the theater as a structural form or building

Web links

Remarks

- ^ Brauneck, Manfred and Schneilin, Gérard: Theaterlexikon . Rowohlt's encyclopedia. Reinbek near Hamburg 1986, p. 66

- ↑ Brauneck, Manfred: The theater of antiquity. Hellas. In: ders .: The world as a stage. History of European Theater. First volume. JB Metzler Verlag, Stuttgart-Weimar, pp. 2-3

- ^ A b Hans Peter Isler: Ancient theater buildings. A manual . Catalog volume (= Archaeological Research . Volume 27 ). Publishing house of the Austrian Academy of Sciences, Vienna 2017, ISBN 978-3-7001-7957-3 , p. 53 f .

- ↑ a b c Hans Peter Isler: Ancient theater buildings. A manual . Catalog volume (= Archaeological Research . Volume 27 ). Publishing house of the Austrian Academy of Sciences, Vienna 2017, ISBN 978-3-7001-7957-3 , p. 54 f .

- ^ Arthur Wallace Pickard-Cambridge: The dramatic festivals of Athens . Ed .: John Gould, David Malcolm Lewis. 2nd Edition. Clarendon Press, Oxford 2003, ISBN 0-19-814258-7 .

- ^ Wilhelm Dörpfeld, Emil Reisch: The Greek Theater. Contributions to the history of the Dionysus Theater in Athens and other Greek theaters . With XII plates and 99 illustrations in the text. Barth & Von Hirst, Athens 1896, p. 366 ( uni-heidelberg.de ).

- ↑ a b Ulrich von Wilamowitz-Moellendorf: The stage of Aeschylus . In: Georg Kaibel, Carl Robert (Ed.): Hermes. Journal of Classical Philology . tape 21 , no. 4 . Weidmannsche Buchhandlung, Berlin 1886, p. 597 .

- ↑ a b c Hans Peter Isler: Ancient theater buildings. A manual . Catalog volume (= Archaeological Research . Volume 27 ). Publishing house of the Austrian Academy of Sciences, Vienna 2017, ISBN 978-3-7001-7957-3 , p. 55 f .

- ↑ a b Raimund Merker: The Προμηθεύς Δεσμώτης on the stage of the 5th century BC Attempt of a scenic reconstruction. In: S. Tsitsiridis (Ed.): Logeion. A Journal for Ancient Theater . tape 4 . Crete University Press, Crete 2014, pp. 100 .

- ↑ a b c Raimund Merker: The Προμηθεύς Δεσμώτης on the stage of the 5th century BC. Attempt of a scenic reconstruction . In: S. Tsitsiridis (Ed.): Logeion. A Journal for Ancient Theater . tape 4 . Crete University Press, Crete 2014, pp. 101 .