Elizabethan theater

The Elizabethan theater is commonly referred to as the theater of the English Renaissance under Queen Elizabeth I (r. 1558–1603) and her successor James I (r. 1603–1625).

A general cultural boom in England in the 16th century led to the emergence of a theatrical system whose dimensions can only be compared with ancient models: for the first time in over a thousand years, professional drama troops existed again. The theater advanced - until all theatrical performances were banned under Puritan rule in 1642 - as a space for social classes to meet. The production of dramatic works grew suddenly, and diverse (and new) theatrical forms emerged. The works that were written for the London stage in these few decades between the 16th and 17th centuries have long been among the most fascinating literary productions in all of European theater. Even William Shakespeare's work falls into this time.

Historical and social requirements

Social change in the 16th century

The rule of Elizabeth I was characterized by a balance of interests between the bourgeoisie and the nobility: Feudal structures gradually lost their importance, the administration of the country was reformed and the importance of parliament was upgraded. Due to the world power status of England and the associated economic rise, a broad middle class had already emerged in the middle of the century, which could claim a say because of its material prosperity; In addition, humanistic educational efforts led to a uniformly high level of education. This opened up the possibility of social advancement - a decisive change compared to the Middle Ages. The Latin education of many citizens was the breeding ground for a drama that was based on classical authors such as B. Seneca , Plautus or Terenz . Their texts were disseminated in school performances.

Jacob's I reign was shaken by numerous domestic political crises (as a result of religious conflicts), but it also gave birth to the vision of national unity for Britain : the study of English history and the English language created important prerequisites for the theater of William Shakespeare.

The Elizabethan theater practice corresponds exactly to the changed social conditions: the audiences of the great London theaters were recruited equally from craftsmen and traders, scholars and members of the nobility - thanks to low admission prices. Without the enormous population expansion in the big city of London - the capital of a world empire - the existence of many theaters would have been unthinkable. A real entertainment district was created there on the so-called Bankside .

secularization

After Henry VIII had created the English national church in 1534 , the second half of the 16th century brought with it, above all, the abandonment of Roman Catholic beliefs. The English language found its way into church services and Bible translations, replaced the Latin - this development formed the breeding ground for a vernacular literature, which was also widely distributed through the printing press . This enabled a literary market to emerge in which playwrights such as Christopher Marlowe or William Shakespeare participated, whose plays appeared in complete editions in the 17th century .

With Francis Bacon's empiricism , a worldview prevailed that was no longer based on (church) dogmas, but on empiricism . Enormous scientific advances in almost all areas shaped the epoch, accompanied by the exploration of the New World , the discovery of which alone meant a great cultural and historical upheaval. Nevertheless, a large part of the population of England continued to believe in psychic events, in magicians and witches ; Queen Elisabeth also had horoscopes drawn up regularly . Accordingly, in Shakespeare's plays there is often a juxtaposition of science and superstition, witches ( Macbeth ) and fairies ( A Midsummer Night's Dream ) populate the stage.

Anthropocentric worldview

Starting from Italy , the Renaissance spread to England in the middle of the 16th century: Humanism turned to ancient traditions and emphasized the freedom of the individual, whom reason raises above the animal kingdom. The emergence of a modern concept of subject favored pieces that emancipated themselves from the typical and instead of fate, placed human action and its consequences in the foreground. In the place of allegorical representations, prototypes of individual psychology appeared. Freedom can always turn negative: The fact that the disintegration of social hierarchies and the breaking away of clear metaphysical explanatory patterns could also be experienced as a threat is impressively demonstrated by the figure of Hamlet - the burden of responsibility for one's own actions here leads to paralysis, to resignation Do nothing.

The melancholic is a paradigmatic figure of the age who appears in many texts, always on the basis of humoral pathology , the most important anthropological theory of the time (also in Hamlet ). Opposite him is the ruthless climber who knows how to stage himself - Niccolò Machiavelli's Il Prinicipe was also received in England (although officially banned). Christopher Marlowe's Doctor Faustus (approx. 1589) shows the consequences of a great obsession with power, as does his Tamburlaine the Great (1587), which shows the rise and death of a Mongolian prince ( Timur ).

Sources

While numerous documents exist on the social effects of the heyday of the English theatrical landscape in the 16th and 17th centuries (including Puritan pamphlets and municipal decrees), references to contemporary performance practice are far less common - apart from the plays themselves. In particular, there is hardly any picture material. An important basis for the reconstruction of the theater situation are therefore the reports of foreign commercial travelers and princely diplomats who visited London: The Observationes Londinienses of the Dutch businessman Johannes de Witt contain, for example. For example, a drawing of the Swan Theater from around 1596, while the Basel doctor Thomas Platter describes in detail to his compatriots a visit to a theater performance.

Another source are relevant written documents such as surviving records in diaries or letters as well as legal texts such as files of legal disputes and contracts for the construction of theater buildings: Two construction contracts for the Hope and above all for the Fortune Theater from the period shortly after 1600 have been preserved, who give more detailed instructions to craftsmen for building a theater. In particular, the contract between the wealthy actor and stage entrepreneur Edward Alleyn and the financially strong actor Philip Henslowe from 1600 on the construction of the Fortune Theater provides more precise information about the appearance, the external and internal dimensions of the theater and the size, arrangement or shape of the stage and galleries. However, this contract contains numerous references to the construction conditions of the Globe Theater , which was built a year earlier , which are not further elaborated, so that numerous ambiguities or contradicting interpretations remain for a reconstruction of the appearance of the former building. Henslowe also kept detailed records of his transactions in diaries from 1592 to 1603. The location and number of the performance venues can be reconstructed from historical views of the city, thus gaining a chronological overview.

In 1989, the remains of a theater south of the Thames were discovered; it is the Rose Theater , also by Philip Henslowe, one of the first large venues on the Bankside. With the help of archeology, numerous theories on Elizabethan theater construction have since been verified in principle, although the stage of the Rose Theater with (at least) two equivalent levels is likely to be rather atypical for the theater of the time. The foundations can be viewed today.

Origins

Medieval forms

In particular the medieval morality , allegorical representation of the eternal struggle between good and evil, as well as the mystery plays - which have been documented since the 14th century - , dramatic versions of biblical events, often integrated into liturgical contexts, seem to have had a great influence on the Elizabethan theater - Different levels of style were mixed there, allusions to everyday life were integrated into religious activities. The closeness to the audience of many Shakespeare's characters can be interpreted as a remnant of the so-called Vice figure: In morality, this personified vice fought with rhetorical skill for the human soul.

Traveling actors

The so-called innyard plays were created as early as the beginning of the 16th century : traveling groups of actors played in the inner courtyards of pubs, where they erected wooden scaffolding. A (now rather unpopular) theory defines the origin of the theater architecture of the time ( Shakespeare stage ): Obviously, the audience was in galleries around the courtyard. The first specific theater buildings (erected in the 1570s) actually still had the characteristics of the traveling theaters and were of a rather provisional character.

The animal fighting arenas, which had been on London's Bankside since at least 1546, had their influence - at least insofar as they provided the infrastructure for the later boom of the theater; the London public were used to enjoying themselves outside the City of London .

Latin drama

Ancient pieces were known to a large audience through humanism; often these were imitated in the vernacular. The plot patterns of the comedies by Plautus and Terence can still be found in Shakespeare, e. B. the motif of the kidnapping of the bride from the house of the wicked father ( The Merchant of Venice ). The Roman tragedy of Seneca, on the other hand, can be used as a model for numerous texts by Christopher Marlowe and Thomas Kyd , the most important authors of the 1580s.

Situation of the actors' troops

history

At the beginning of the 16th century the first professional actors' troops developed, made up of traveling showmen and a growing number of unemployed . Obviously, socially disadvantaged groups in particular saw acting as a good source of income; the number of companies grew strongly after 1550. In response, the Vagabond Act of 1572 in London only allowed actors under the patronage of a nobleman or two justice of the peace to appear. The first patent was granted in 1574 to the troops of the Earl of Leicester . Then in 1583 - with the best actors of the time - the Queen Elizabeth's Men were founded.

With a further ordinance of 1598 the patronage capacity was limited to members of the high nobility and other official dignitaries were withdrawn. As a result, the number of drama troops in the favor of the court steadily increased.

The patronage system brought enormous advantages for the actors' troops: While in other European countries in the 18th century the profession of the actor was still classified as morally questionable, often on a par with prostitution , actors in England were socially respected. Shakespeare and Richard Burbage are even known to have held honorary posts at court. In addition, the noble patrons were able to give their companies financial support in an emergency - it is not known whether grants were received regularly, but it is unlikely: the troops acted as independent business enterprises and by no means as service providers for the pleasure of individual noblemen. They were geared towards safeguarding and expanding their business operations and generally made a profit.

As the only major city on the island, London offered the greatest potential for spectators; the drama groups therefore tried determinedly to settle in this city if possible.

The death of Queen Elizabeth brought many changes: while in 1597 only two drama troops (the Lord Chamberlain's Men and the Admiral's Men ) held the license to play in London, the court now took over all the companies: the Lord Chamberlain's Men became them King's Men . In a decree of 1598, the Privy Council stipulated that there should only be two theater groups in London.

Important troops

- Leicester's Men : The first licensed group of actors played at James Burbage's Theater in the 1570s .

- Derby's Men : The company can be traced back to the 1560s. From 1594 she was named Lord Chamberlain's Men . Under Burbage and Shakespeare she advanced to the most important acting troupe, had numerous appearances at court. In 1603 it was renamed King's Men - the king was the new patron, and they played in the Globe Theater and the Blackfriars Theater .

- Admiral's Men : Philip Henslowe's company was renamed Prince Henry's Men in 1603 ; she played in Fortune .

organization

The companies were financially organized as a form of holding company. Partnership ( sharers ) were generally the actors themselves, who then stagehands and extras hired and all made decisions on business policy. Sometimes they were in close contact with an impresario who acted as a financier and stage lender and participated in the box office profits. By acquiring a partnership with a stake between 50 and 70 pounds at the turn of the century, not only was the theater company's share capital built up, but at the same time an attempt was made to bind the shareholders to the troupe. The respective share was only paid out in the event of an amicable separation; if the separation was not amicable, the share was lost. Various written agreements later also provided for a fixed contract term and contractual penalties for late appearing or drunkenness at performances and the like. If a troupe did not have its own theater, it had to raise the rent for a venue - Philip Henslowe got rich by building theaters. From 1599 Shakespeare held ten percent of the Lord Chamberlain's Men and was also involved in the construction of the Globe Theater , which gave him a certain level of prosperity. If the troupe did not have the money for the necessary stage equipment or the purchase of text books, the theater owner, in addition to the impressario, granted a loan for these costs and kept an additional part of the game income for repayment. At the time, the theater owners were keen to keep the drama troops loyal to them in the long term, which was made easier by their indebtedness. Among the major actors in the Elizabethan theater, only the King's Men were likely to have remained financially independent. One of the reasons for this was that the Burbages gave some of their fellow actors, including Shakespeare, a share of the funding, and therefore the ownership and revenue of the newly built Globe Theater .

The troops each consisted of about ten to twelve actors as well as the so-called boy actors , the performers of the female roles (because women were not wanted on the stage). They had a large repertoire, often playing over 30 pieces at the same time - only to be achieved through the role system , ie the cast according to certain types.

The book-keeper played a central role, processing the author's manuscript into individual role books ( parts ), ensuring the organization and the precise sequence of the performance and also acting as a prompter . None of the actors received the text for the entire play, because the playwrights feared pirated prints and the financial losses associated with them. The prices for new plays put a heavy burden on the drama troops; In addition to the purchase of the manuscripts by the theater groups themselves, they were also bought up by Henslowe as a middleman and given to the troops for a fee. In 1598 Henslowe paid five pounds for a piece (a craftsman at the time was making a shilling a day by comparison); In 1615 the price had already risen to £ 20. Since a new piece was needed about every 14 days, the cost of purchasing new manuscripts devoured a large part of the income. It was not until the last decades of the 16th century that the purchase of new pieces fell significantly to around four pieces per year, as an extensive repertoire was now available. At the time, the acting groups were thriving commercial enterprises that provided for the livelihood and prosperity of a group of around 40 to 50 people who were involved in the entire theater business. Rehearsals for new performances probably took no more than two to three weeks. Directors were unknown to the Elizabethan theater; However, the revised copies of the author's manuscripts ( foul papers ) for performance purposes (so-called prompt books ) usually contained stage or stage directions added later. As a rule, the authors of the pieces had no further share in the performances after the sale of the manuscript.

Children's troops

A special feature were the pure children's troops, which were mainly in the private playhouses such as B. the Blackfriars played. They were recruited from Latin students and the singers of church choirs and - as contemporary documents show - were perceived by adult actors as great competition. Often the child actors switched to the big companies in the course of their adolescence to take on female roles as boy actors .

State supervision of theater operations

The responsibility for the entire theater business lay with the Lord Chamberlain , to whom the responsibility for this area had been assigned by the Privy Council as the highest organ of government. The supervision of the theater was exercised by the Office of the Revels under the direction of a Master of the Revels , who was able to carry out his office with great independence. Originally he was responsible for organizing stage performances and other festive events; after the drama group settled in London, his competencies were expanded and in 1581 he was also given censorship of the plays listed.

The holder of this office had to pay 150 pounds a year for the performance of his office, but had a considerable monopoly of income from the large number of pieces played due to the license fees and censorship fees, which rose from initially seven shillings to two pounds per piece. In addition to the task of censorship, he was also responsible for monitoring compliance with health and religious requirements for gaming operations. The theaters had to be closed especially during Lent or the plague epidemics. However, this endangered the economic livelihoods of the drama troops and theater owners, as the income was lost with ongoing financial obligations.

The means of closing the theaters for health reasons also gave the anti-theater magistrate of the City of London an often used, effective way to hinder theater operations.

Since the prohibition to play during Lent was often ignored and the Master of the Revels often tolerated such violations, possibly in part through a purchase dispensation, his responsibility for the control of the theater was finally withdrawn and in 1642 with the Closing of the theaters perceived by Parliament itself.

Drama

In principle, drama was subordinated to the ancient division into comedy and tragedy , although mixed forms were becoming increasingly popular. A specialty of Elizabethan drama are the history plays . With a few exceptions ( Ben Jonson's works, for example), a departure from the strict Aristotelian poetics in favor of the most spectacular plots possible can be observed: The comedies in particular often show heroes traveling through numerous exotic countries and having to endure various adventures (e.g. Sir Clyomon and Sir Clamydes , around 1580).

tragedies

Revenge dramas based on the model of Seneca were very well received by the public; to be mentioned here are e.g. B. Thomas Kyd's Spanish Tragedy or John Webster's Duchess of Malfi - bloody stagings of various acts of violence. From antiquity, appearances by ghosts in particular were adopted as a dramaturgical element, which motivate the action: the deceased usually calls on the hero to avenge his death. Particular interest in the conduct of action then applies to the fight against social resistance (also of a moral nature). Another form that enjoyed great popularity is the marriage tragedy, as it still lives on in Othello , for example : here adultery is treated with physical and emotional punishment before the characters involved can be reconciled in death.

Comedies

Thomas Dekker ( The Shoemaker's Holiday ) is (like Thomas Middleton with A Chaste Maid in Cheapside ) a representative of city comedy , which satirically deals with city life. Ben Jonson's comedies ( Volpone ), on the other hand, deal with the conflict between the individual and the social order, and also deal with ancient poetics of rules. Jonson is considered an author who wrote primarily for the courtly setting. He gave the satire corrective abilities based on Cicero . John Lyly, on the other hand, primarily created love comedies, the plot structure of which was based on novels: The complex fable here shows a couple who face numerous obstacles (= peripeties ). must overcome before it can come together.

Histories

With the increasing national consciousness of the English, which was due to global political successes, such as the destruction of the Spanish Armada, the interest in the history of England and Europe grew. The theater took up this interest and so the histories or history plays came about . Dramas about English kings, such as " Richard III " or " Henry V " by William Shakespeare , "Edward II" by Christopher Marlowe or "Edward I" by George Peele , as well as the anonymous work "A Larum for London" fall under this category "about the Spanish fury in Antwerp.

Mask games

Mask games ( masques ) are a courtly form that flourished especially under James I - they were supposed to represent the power of the king. These are performances on stage with spectacular effects and dance interludes. Members of the court often took part in the performances. Well-known masques include the Masque of Blackness (1605) and the Masque of Queens (1609).

Theater construction

Theater in the country

Although the research is primarily focused on the situation in London, performances in smaller towns in England were probably also common - permanent theaters are unlikely to have existed here. It has been handed down that the large drama troops undertook regular tours through the province and played there in squares, in council houses and guild houses, often with reduced staff and equipment. Shakespeare himself saw some of these guest performances in his youth - the Queen's Men made several trips to Stratford-upon-Avon .

Location of the theater in London

Fixed tavern theaters developed early on from the temporary stages of the traveling troops. In London, this was banned by decree in 1596, as the number of lawsuits from local residents increased - in response, the ensembles moved to liberties , ie areas outside the city's jurisdiction. That is why the classic public playhouses , the large public theaters, were located in the south or north of the city center. A suitable infrastructure existed here : brothels and animal fighting arenas formed the neighborhood of the venues.

Construction methods

A basic distinction is made between the public playhouses on the bankside and the private playhouses - these are covered performance options in a central location, which, due to their independence from weather and light conditions, could also be used in winter. For the theater at court, however, its own rules apply.

public playhouses

history

The origin of the public playhouses is assumed by recent research to be the combination of three already existing and proven forms of construction and design of the theater, on the one hand on the medieval street and hall stages, on the other hand on the oval and round large arenas for animals and tournaments or sports competitions go back. The latter, for their part, presumably based themselves on the Roman model of the amphitheater . By erecting wooden platforms in the courtyard of these buildings, their function was expanded. The advantage of such a construction is the great adaptability: If necessary, the theater can be converted back into an arena.

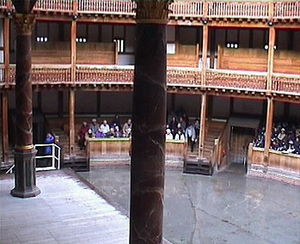

Little is known of London's first permanent theater building: In 1567, John Brayne built the Red Lion in Whitechapel , east of the city center. It remains questionable which troop it played. In 1576, James Burbage had the theater built in north London , and The Curtain was built nearby a year later . In 1599 his son Richard Burbage dismantled the wooden structure of the theater - the building material was used to create the Globe on the Bankside, ie on the south bank of the Thames. An unbelievable density of theaters was to develop here: The Rose was already in place in 1587, and the Swan was added in 1595 . In 1600 the Fortune followed as competition to the Globe Theater and in 1613 the Hope . In 1613 the Globe burned down - in 1614 the second Globe was erected on the same site (with significantly different architecture). The competing Fortune Theater burned down in 1621, but was largely rebuilt in its original form in 1623. After the Puritans closed the public theaters, the Fortune was used for occasional secret performances until it was finally demolished in 1160.

Construction

Since none of the theaters from the Elizabethan era have survived, their construction and shape can only be reconstructed from contemporary reports, descriptions and other documents such as records in diaries, files of legal disputes or contracts and letters, as well as from references in the dramatic texts themselves. Despite lengthy research work, however, it has not yet been possible to clarify all structural details unequivocally; the surviving documents are by no means without contradictions and, moreover, cannot always be clearly interpreted.

The floor plans of the public playhouses were round or polygonal (the only exception here was the Fortune with its square floor plan). The half-timbered construction of these buildings consisted of a wooden framework with lined spaces, the roof was covered with either thatch or wooden shingles ( thatch or tile roofing ). The stage building ( tiring house ) with storage rooms and changing rooms was integrated into the round of the theater . The open courtyard ( yard ), surrounded by three floors of galleries, housed the social underclass ( groundlings ) during the performance . Here protruded the rectangular or delta-shaped stage - a wooden platform on stumps of columns, probably surrounded by a balustrade . This platform had up to four trap doors ( traps ) which were used for ghost appearances . The space below the stage was said to be bright - a holdover from the mystery play tradition. The stage front ( tiring house facade ) was broken through - up to five - stage doors , above which was the upper stage , next to it boxes for noble spectators, called lord rooms . The so-called hut (= hut ). rested on large pillars across the back of the platform. In some theaters there was even a flying machine here , and a flag was hoisted over the hat during performances .

The exact construction of the tiring house facade , ie the rear wall of the stage, is still unclear . One of many theories suggests an opening to an inner stage ( inner stage - a term that was not used by Shakespeare's contemporaries), which could be used for scenes in which the characters make a surprising discovery. Other models, on the other hand, work with curtains ( arras ) in front of the stage doors or tents, which could be set up in the rear area of the platform . The exact characteristics of the upper stage as the second level of play (e.g. for balcony scenes) are also unclear; However, it is likely that the gallery was simply used for this, and musicians also sat on it if necessary.

private playhouses

The form and construction of private theaters is even less well documented than that of public ones, as they were not a novelty that caught the attention of travelers and was reflected in more detailed descriptions or diary entries.

However, some references can be found in the filing of litigation. After that it looks like the private stages have been built into large rectangular halls. The respective stage was erected on one of the front sides. However, the so-called lord boxes , ie boxes for wealthy spectators, were presumably to the right and left . Benches were set up in front of the stage for the rest of the audience. The main differences to the public theaters were, besides the size and the arrangement of the audience, that the private stages were housed in closed rooms, where artificial light could also be used in the dark. The visitor capacity, however, was much lower: if the public playhouses held up to 3,000 spectators, the figures for the private theater halls were more likely to be around 400 to 500. In general, the entrance fees in private theaters were therefore considerably higher, which resulted in a different visitor structure with an audience from the wealthier classes. The distribution of seats in the private stages essentially corresponded to the arrangement customary to this day and in this respect paved the way for the later form of modern illusion theater.

Theater at court

The performance practice and stage equipment for performances at the English court can be deduced relatively precisely from the abundant documentary material of the Revels Office, in contrast to public and private theaters. This authority, which was part of the royal household and was responsible for the events and implementation of festivities at the court, preferred dramas and masques for festive events around Christmas and New Year, after assessing the game repertoire of the leading actors in accordance with the The Master of the Revels made a corresponding pre-selection for the Queen’s wishes and invited the selected groups of actors to a test performance with their respective plays. After the final selection of suitable pieces for the planned court performance, the Master of the Revels was also entitled to redesign the stage text of the planned works by deleting or adding text passages.

The documents of the Revels Office show that a great deal of effort was made in the selection of the costumes for the actors and the stage decoration, as well as in setting up the sets. From the surviving files it can also be seen that the theater performances at court in Shakespeare's time were by no means, as is often mistakenly assumed, largely without a backdrop. A large wooden construction was erected as a stage on the narrow side of the large festival hall; Whether the stage could be separated from the audience by a curtain can no longer be clarified with sufficient certainty.

The audience at these performances consisted of an extremely homogeneous, educated class of dignitaries of the state or officials of the royal household including their wives. Drama that were initially designed for court performances usually contained a wealth of current references such as allusions to court gossip, current events or political constellations and the like.

Most of the plays performed at court, however, had previously been performed in public theaters. The same actors therefore performed their plays under completely different stage conditions. The public theater stage offered a largely neutral platform in the midst of an audience of all classes. On this playing area, the tradition of popular theater could be followed up and the anti-illusionist tendencies as well as the original character of the stage performance could be most likely accentuated. In contrast, the court performances in front of a homogeneous, humanistically educated audience from the upper classes were more likely to focus on an illusionistic stage design and realistic presentation of the game. This tendency then had an impact on the performances in public and private theaters and shaped the mixture of creating and breaking illusions that was characteristic of the time. After the theater was closed between 1642 and 1660, the newly opened theaters geared their performances to the tastes of the aristocratic class that dominated the audience, so that the previous references to the tradition of popular theater were completely lost. In accordance with the classicist ideal of illusionist realism, the development towards the modern peep-box stage began to increase.

A completely different repertoire (the allegorical-operatic masques ) caused different performance conditions here. Inigo Jones ' Banqueting Hall in Whitehall is typical of courtly theater, with spectators and actors sitting opposite one another. Efforts to take over the Italian stage set are documented. B. Inigo Jones' plans for a theater in cockpit-in-court . Here, too, the concept of the peep show stage was anticipated.

Performance practice and game aesthetics

Game operation

While at first it was only played on holidays (which the Puritans prevented), from the 1580s on it can be assumed that it will be performed on all working days . At court, the theater season lasted from November to Easter, in the public and private playhouses, on the other hand, games were held throughout the year, and in winter probably also in taverns - despite the corresponding bans.

Performances usually started in the afternoon (ie during regular working hours) and lasted two to four hours. Good lighting conditions were a prerequisite, as there was no artificial lighting in the public playhouses . Trumpets announced the beginning of the game, on the hat also a flag was hoisted, which was visible from afar - because the audience finally had to travel the Thames from the other side, either on the London Bridge or a ferry . Afterwards, even after tragedies (!), The audience was always presented with a jig , a burlesque folk dance.

Stage equipment

The use of decorations has long been a point of contention in research: Older literature assumes that the stage was completely empty and localizations were only made through the piece text. The concept of the word backdrop has become established for this process . Indications of this are the numerous and detailed descriptions of the location in the character speech of the dramas. More likely, however, are emblematic backdrops, ie set pieces that point to a certain location (such as a throne or tents) and - qua linguistic characterization - can be used variably. There is also evidence of the use of place-name signs, for example above the stage doors.

The stage z. B. the second Globe Theater had enormous machinery: In addition to an aircraft that could be used to lower decorative elements from the hat onto the stage (and thereby accelerate the conversion), there was also the possibility of several actors in the To sink the stage floor. Pyrotechnic effects have also been proven.

Costumes

The costumes were primarily characterized by their splendor - historical accuracy was less in demand. Often the clothing was used by nobles who had bequeathed them to their servants after their death. Certain epochs or countries could be indicated by individual attributes - such as headgear or colors.

Acting style

From the Shakespearean dramas one can sometimes infer certain staging conventions. B. all appearances explicitly announced - from which one deduces that the actors were standing in the front area of the platform , and that additional characters had to travel a long way before they could take part in the action. It can also be considered almost certain that the performers spoke quickly, because the average duration of the performance was very short in relation to the length of the texts.

Much remains speculative, of course. B. propose several theories about audience involvement; were the public playhouses noisy, overcrowded arenas, in which the groundlings constantly commented on what was happening on stage, to which the actors themselves reacted? Or was a playwright like Shakespeare able to captivate his audience, was there a devout silence during the performances?

literature

- Muriel C. Bradbrook: Shakespeare. The poet in his world . Methuen, London 1989, ISBN 0-416-73690-4 .

- Albert R. Braunmuller, Michael Hathaway (Eds.): The Cambridge Companion to English Renaissance Drama. 2nd Edition. Cambridge 2003, ISBN 0-521-52799-6 .

- Edmund K. Chambers: The Elizabethan Stage . Clarendon Press, Oxford 1974, ISBN 0-19-811511-3 (4 volumes. Repr. Of the Oxford 1923 edition).

- Andrew Gurr: The Shakespearean Stage. 1574-1642 . CUP, Cambridge 2005, ISBN 0-521-42240-X .

- Dennis Kay: William Shakespeare. His Life, Work, and Era . Twayne Publ., New York 1995, ISBN 0-8057-7063-1 .

- Thomas Kullmann: William Shakespeare. An introduction . Erich Schmidt Verlag, Berlin 2005, ISBN 3-503-07934-3 .

- Alois M. Nagler: Shakespeare's Stage . Yale University Press, New Haven Conn. 1991, ISBN 0-300-02689-7 .

- Ina Schabert (Ed.): Shakespeare Handbook. Time, man, work, posterity. 4th edition. Kröner, Stuttgart 2000, ISBN 3-520-38604-6 .

- Ulrich Suerbaum: The Elizabethan Age . Reclam, Stuttgart 2007, ISBN 978-3-15-008622-3 , Chapter 4: Das Theater, pp. 399–472.

- Robert Weimann , Douglas Bruster: Shakespeare and the Power of Performance - Stage and Page in the Elisabethan Theater . CUP, Cambridge 2008, ISBN 978-0-521-89532-3 .

- Wolfgang Weiß: The drama of the Shakespeare era. Attempt at a description. Kohlhammer Verlag, Stuttgart et al. 1979, ISBN 3-17-004697-7 . (Accessible online as a PDF file at epub.ub.uni-muenchen.de )

Web links

- http://search.eb.com/shakespeare - Encyclopædia Britannica : Shakespeare and the Globe

- http://shakespearean.org.uk/elizthea1.htm - Lecture on Elizabethan Theater

See also

Individual evidence

- ↑ Wolfgang Weiß: The drama of the Shakespeare time. Attempt at a description. Kohlhammer Verlag, Stuttgart et al. 1979, ISBN 3-17-004697-7 , p. 11. (Available online as a PDF file at epub.ub.uni-muenchen.de ).

- ↑ See Wolfgang Weiß: The Drama of Shakespeare's Time. Attempt at a description. Kohlhammer Verlag, Stuttgart et al. 1979, ISBN 3-17-004697-7 , here chapter 1.2: The London theaters, here mainly p. 30ff. and Helmut Castrop: The Elizabethan Theater. In: Ina Schabert (Ed.): Shakespeare-Handbuch. Time, man, work, posterity. 5th, revised and supplemented edition. Kröner, Stuttgart 2009, ISBN 978-3-520-38605-2 , pp. 71–116, here especially pp. 77ff. See also the information in the Encyclopædia Britannica . on britannica.com . Retrieved January 21, 2019.

- ↑ See Wolfgang Weiß : The Drama of Shakespeare's Time. Attempt at a description. Kohlhammer Verlag, Stuttgart et al. 1979, ISBN 3-17-004697-7 , pp. 17-21. Cf. also Ina Schabert (Ed.): Shakespeare-Handbuch. Time, man, work, posterity. Kröner, Stuttgart 1972, ISBN 3-520-38601-1 (5th, revised and supplemented edition, ibid. 2009, ISBN 978-3-520-38605-2 ), pp. 101-103.

- ↑ See Wolfgang Weiß : The Drama of Shakespeare's Time. Attempt at a description. Kohlhammer Verlag, Stuttgart et al. 1979, ISBN 3-17-004697-7 , p. 23 ff.

- ↑ See Wolfgang Weiß : The Drama of Shakespeare's Time. Attempt at a description. Kohlhammer Verlag, Stuttgart et al. 1979, ISBN 3-17-004697-7 , pp. 17-21. Cf. also Ina Schabert (Ed.): Shakespeare-Handbuch. Time, man, work, posterity. Kröner, Stuttgart 1972, ISBN 3-520-38601-1 (5th, revised and supplemented edition, ibid. 2009, ISBN 978-3-520-38605-2 ), pp. 103-105.

- ↑ See Wolfgang Weiß : The Drama of Shakespeare's Time. Attempt at a description. Kohlhammer Verlag, Stuttgart et al. 1979, ISBN 3-17-004697-7 , pp. 23-25 and 42 f. See also Ina Schabert (Ed.): Shakespeare-Handbuch. Time, man, work, posterity. Kröner, Stuttgart 1972, ISBN 3-520-38601-1 (5th, revised and supplemented edition, ibid. 2009, ISBN 978-3-520-38605-2 ), pp. 107, 112 and 77 f.

- ↑ See Wolfgang Weiß : The Drama of Shakespeare's Time. Attempt at a description. Kohlhammer Verlag, Stuttgart et al. 1979, ISBN 3-17-004697-7 , p. 25 f. Cf. also Ina Schabert (Ed.): Shakespeare-Handbuch. Time, man, work, posterity. Kröner, Stuttgart 1972, ISBN 3-520-38601-1 (5th, revised and supplemented edition, ibid. 2009, ISBN 978-3-520-38605-2 ), p. 115 f.

- ↑ Christopher Marlowe: Edward II. Nick Hern Books, London 1997.

- ↑ George Peele: The Chronicle of King Edward The First. George Kelsey Dreher (Ed.), Longshanks 1998 [1584].

- ^ Anonymous: A Larum for London, or The Siedge of Antwerpe with the ventrous actes and valorous deeds of the lame soldier. London 1602.

- ↑ See Ina Schabert (Ed.): Shakespeare-Handbuch. Time, man, work, posterity. 4th edition. Kröner, Stuttgart 2000, p. 82 ff.

- ↑ See Wolfgang Weiß: The Drama of Shakespeare's Time. Attempt at a description. Kohlhammer Verlag, Stuttgart et al. 1979, ISBN 3-17-004697-7 , p. 29 ff. Cf. also Ina Schabert (Ed.): Shakespeare-Handbuch. Time, man, work, posterity. 4th edition. Kröner, Stuttgart 2000, pp. 71-78, and Ulrich Suerbaum : Shakespeares Dramen. UTB, Stuttgart 2001, ISBN 3-8252-1907-0 , pp. 46-54.

- ↑ See Wolfgang Weiß: The Drama of Shakespeare's Time. Attempt at a description. Kohlhammer Verlag, Stuttgart et al. 1979, ISBN 3-17-004697-7 , p. 33 f. Cf. also Ina Schabert (Ed.): Shakespeare-Handbuch. Time, man, work, posterity. 4th edition. Kröner, Stuttgart 2000, p. 81 f.

- ↑ See Wolfgang Weiß: The Drama of Shakespeare's Time. Attempt at a description. Kohlhammer Verlag, Stuttgart et al. 1979, ISBN 3-17-004697-7 , pp. 34-37.

- ↑ Cf. Ina Schabert (Ed.): Shakespeare-Handbuch. Time, man, work, posterity. 4th edition. Kröner, Stuttgart 2000, p. 96 f.