Queen Elizabeth's Men

The Queen Elizabeth's Men were an acting company of the Elizabethan Theater . Founded in 1583 on an order from Elizabeth I , it was the dominant theater company in the 1580s until it was replaced by the Admiral's Men and the Lord Chamberlain's Men in the following decade .

founding

Since the Queen formed the troupe herself, the circumstances are well documented by Elizabethan standards . The formation order was given on March 10, 1583 to Edmund Tilney , at that time the Master of the Revels ; the task of putting the staff together was taken over by Francis Walsingham , the head of the intelligence services at Elizabeth's court. At that time the Earl of Sussex was dying. He was the official at court who had the early Lord Chamberlain's Men in his patronage. A protector was very important for actors at this time. When the Elizabethan Poor Laws were changed with a law of 1572, the situation of traveling actors changed: those who did not have patronage from a nobleman could be classified as a vagabond and subject to a range of penalties. However, those who enjoyed such protection were legally more secure than before. The Queen's Elizabeth's Men thus filled the void that the first and later (and then very important) Lord Chamberlain's Men left open. Although other acting companies also played for the Queen, the Queen's Men were primarily responsible for the entertainment at court.

Assembling such a new force apparently required Walsingham's strong arm, since as the Queen's high official he was free to choose the best actors from the most successful troops of the time and incorporated them into the Queen's Men. On behalf of the Queen and the Privy Council , the opportunity was created here to combine theater and espionage activities, as the actors traveled frequently both nationally and internationally and thus could serve the crown in a variety of ways, including collecting information for Walsingham's espionage network .

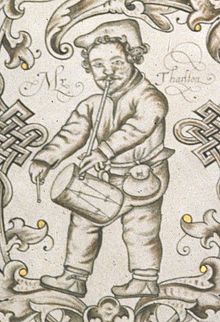

The Leicester's Men , then the leading actors of the day, lost three members to the Queen's Men: Robert Wilson , John Laneham and William Johnson, while the Oxford's Men lost two of their leading men, brothers John and Laurence Dutton; and the Sussex's Men were stripped of their boss, John Adams, and the famous clown, Richard Tarlton . Other prominent members of the new cast included John Singer, William Knell and the "inimitable" John Bentley. Tarlton soon became the star of the Queen Elizabeth's Men - "for a wonderfully copious, pleasant, spontaneous [improvised] joke, he was the wonder of his time."

It was assumed that Elisabeth also pursued a certain court political motive behind the formation of the drama troupe. Robert Dudley, 1st Earl of Leicester and Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford use their ensembles to vie for the favor of the royal family on the occasion of the annual Christmas celebrations at court; Elisabeth and her council occasionally condemned this competition and the egos of the nobles, but they did not succeed in curbing this behavior. By picking the best actors from her ensembles, she pushed back the ambitious aristocrats, asserting her priority.

status

Their creation made the Queen Elizabeth's Men unique among the drama ensembles of the time: "The Queen's Men were a deliberately political troupe from the start, and their repertoire seems to have followed the path that Sir Francis Walsingham undoubtedly intended for them." In the pieces they performed “nobody found a conflict or irritation that did not move within the interests of Tudor conservatism”. The political controversies that later hit other actors and plays, such as: B. The Isle of Dogs , The Isle of Gulls and others - could not even come about with the Queen's Men. However, in 1589, shortly before their dissolution, they could still have come into conflict with the authorities. Possibly because they got too involved in the Martin Marprelate controversy by parodying Martin on the public stage.

Despite the restrictive Theater laws within the City of London it was the Queen's Company officially allowed to play in two locations in London: the converted to theater venues courtyards (See Inn Yard Theater ) of restaurants ( pubs ) Bell Savage Inn on Ludgate Hill and the Bell Inn on Gracechurch Street. Both inns were within the city, near Bishopsgate in the western city walls . The former had an uncovered courtyard, while the other possibly had a roof. With this arrangement, the Queen Elizabeth's Men may have anticipated the idea of year-round theatrical performances, as the King's Men practiced a quarter of a century later with the alternating examples of the Globe Theater and Blackfriars Theater .

Potency

The formation of the troupe took advantage of the growing versatility and professionalism of the actors of the time. A separate ensemble of changing actors had already played at Elisabeth's court in the years and decades before; however, the perception of general dissatisfaction prevailed and the court relied on ensembles of child actors for higher quality entertainment . John Stow wrote in his annals in 1615:

"Comedians and stage-players of former times were very poor and ignorant ... but being now grown very skillful and exquisite actors for all matters, they were entertained into the service of various great lords: out of which there were twelve of the best chosen, and ... were sworn the Queen's servants and were allowed wages and liveries as Grooms of the Chamber. "

“Comedians and stage actors of earlier times were poor and uneducated ... but now they grew up to be competent and exquisite actors for all areas, they were placed in the service of various great masters: from this the twelve best were chosen and ... sworn in as servants of the Queen and they were granted salaries and liveries as employees of the Chamber . "

The troops maintained the court mainly in winter; and in the summer they toured the cities of the English Shires , although they could have reached Scotland in 1589. In London they were initially only allowed to play in the two large inns mentioned above; but in later years they may have appeared at James Burbage's Theater .

The large number of the 12 founding members also shows a new path taken by the theater: The Queen Elizabeth's Men was the first large acting company in the Elizabethan theater , twice as large as its predecessors. In the 1570s, for example, the Sussex's Men had six members. When Elsinore Castle received a troupe of traveling actors to perform the second scene of Act 2 of Hamlet , they consisted of only "four or five" players. The performers in Sir Thomas More consisted of "four men and one boy ...". The size of the new troupe now made it possible to bring a new kind of drama to the stage and to a far greater extent than ever before. In particular, the development of the historical performances , a characteristic feature of the later 1580s and 1590s, was not possible without a large ensemble. The Famous Victories of Henry V (approx. 1583, author unknown), one of the earliest works of this kind, has 20 different speaking roles in the first 500 lines and the pieces that followed, including Shakespeare's historical dramas, were structured in the same pattern. Just as the great Hollywood feature films were created 450 years later , the new, extensively cast works represented a leap to a new level of complexity and professionalism that would have been unplayable before the founding of the Queen's Men. When the Queen's Men were finally replaced at court in the winter of 1591/92, it took a large team of members of the Admiral's Men and Lord Strange's Men to fill the gap.

This phenomenon can be found in a reconstruction of a performance of The True Tragedy of Richard III (probably second half of the 1580s; author unknown). Here four actors played seven different roles and even the boy actors had, which was rather unusual for them, to also play two roles. So the roughly dozen actors of the Queen's Men alone served the 68 different roles in the play.

Decline

In 1587 the actor William Knell got into an argument with a company colleague named John Towne and was fatally injured in the sword fight that followed. Richard Tarlton died the following year, all at a time when the Queen Elizabeth's Men faced additional competition from the Admiral's Men and their star Edward Alleyn , who preferred plays by the popular Christopher Marlowe . The character of the troupe began to change as the gaps were filled in by Lord Strange's Men, including John Symons. And with that different emphasis and orientation, they also seemed to have lost the prestige they had before. They played again at court in the Christmas season of 1591. The interruption of the entire theater business in London between 1592 and 1593 by an outbreak of the plague brought many actors to the brink of their existence. The Queen's Men were particularly hard hit. When the companies reorganized in 1594, especially in the reorganized companies of the Lord Chamberlains and Admirals, the Queen Elizabeth's Men were already history. John Singer continued his stage career with the Admiral's Men for a decade; the other actors toured the provinces and ultimately sold their textbooks to London stationery dealers, marking the end of their acting career. A core of the force may have existed for a few years. Under a different name and with different patronage . Two of the former members of the Queen's Men, John Garland and Francis Henslowe , played e.g. B. later with the Lennox's Men (Patron: Ludovic Stewart, 2nd Duke of Lennox ) and toured across the country from 1604 to 1608.

Performed pieces

Since some of her pieces were also printed in the early 1590s, limited parts of the Queen Elizabeth's Men's repertoire are known today. The following plays were performed by the troupe ( unless stated otherwise: author unknown ):

- The Famous Victories of Henry V

- Friar Bacon and Friar Bungay ( Robert Greene )

- James IV (Robert Greene)

- King Leir

- A Looking Glass for London and England (Robert Greene and Thomas Lodge )

- The Old Wives' Tale ( George Peele )

- Sir Clyomon and Sir Clamydes

- The Troublesome Reign of King John

- The True Tragedy of Richard III

Individual evidence

- ^ Chambers, volume. 2, pages 104 ff.

- ↑ McMillin; MacLean (1998) p. 27

- ↑ McMillin; MacLean (1998), pages 5, 11 and 12.

- ↑ Chambers, Volume 2, p. 105.

- ^ Gurr, pp. 28, 32.

- ↑ McMillin, Scott. The Elizabethan Theater and "The Book of Sir Thomas More." , Cornell University Press , Ithaca, NY 1987, p. 59.

- ↑ The author of an anonymously written treatise on that controversy entitled Martin's Months minde, That is, A Certaine report, and true description of the Death and Funeralls of Old Martin Marre-prelate, the great makebate of England, and father of the Factious , boasted that "hir maiesties men" were among those pleased to "returne [the Martinists] the cuffe, instead of the glove, and hiss the fooles from off the stage." London: Printed by Thomas Orwin, 1589. S108299, D3.

- ^ Gurr, pages 119 and 120.

- ↑ Chambers, Volume 2, p. 104; Halliday (1964), p. 398.

- ↑ McMillin (1987), pp. 55-60.

- ↑ For the personnel expenditure see also Sir Thomas More .

- ↑ McMillin; MacLean (1998), p. 105.

- ^ Halliday (1964), p. 277.

literature

- Edmund Kerchever Chambers : The Elizabethan Stage 4 volumes, Clarendon Press, Oxford 1923.

- Andrew Gurr . The Shakespearean Stage 1574-1642. Third edition, Cambridge University Press , Cambridge 1992.

- FE Halliday : A Shakespeare Companion 1564-1964. Penguin, Baltimore 1964.

- Scott McMillin: The Elizabethan Theater and "The Book of Sir Thomas More." , Cornell University Press, Ithaca New York 1987.

- Scott McMillin and Sally-Beth MacLean: The Queen's Men and Their Plays . Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1998.