Oceanus

Oceanus ( ancient Greek Ὠκεανός Okeanos , Latin Oceanus ) is in Greek mythology the divine personification of the inhabited world runaround mighty stream which - together with the sea goddess Tethys as the father of all - rivers and Oceanids applies and occasionally even as a father of gods and Origin of the world appears.

etymology

In his journal for comparative linguistic research in the field of German, Greek and Latin, Adalbert Kuhn already found the exact phonetic correspondence between the Vedic āśáyāna- (“lying on [the water]”), an attribute of the stone dragon Vṛtra , and the Greek Ὠκεανός Ōkeanós noticed. Michael Janda agreed to this equation in 2005 and reconstructed a common Indo-European root * ō-kei-ṃ [h 1 ] no- "lying" for both words , which is related to the Greek κεῖται keítai , German "lie" . Janda refers to black-figure vase depictions on which Okeanos possesses a serpent's body and which can prove a mythological parallel between the Greek god of the sea or river and the Vedic dragon Vṛtra.

In addition, Janda pointed out another etymological parallel between the Greek ποταμός potamós , German 'broad body of water' and the Old English fæðm 'embrace, fathom ' (cf. the wooden unit of thread ), which is particularly in the old English Helena poem (verse 765) as dracan fæðme 'the dragon's embrace' and is also related (via ancient Germanic * faþma ) to Old Norse Faðmir or Fáfnir , the name of a dragon from the Völsunga saga of the 13th century. The phonological findings make it possible to derive all three terms from Indo-European * poth 2 mos "spreading" and thus to closely link the Greek word for a "broad river" with the two Germanic expressions, which in different contexts are the "embrace" by a dragon describe.

In contrast, Robert SP Beekes connected the god's name with a pre-Greek form * -kay-an- .

myth

For Homer, Oceanus is both the origin of the world and the current that flows around the world and is distinguished from the sea. It is the origin of the gods as well as of all rivers, seas, springs and wells, of which only Eurynomials and Perse are named. His wife is the sea goddess Tethys , with whom, according to Hera's story, he is in conflict and who therefore does not produce any further descendants:

|

|

This narrative of the separation of the original couple, otherwise inconceivable in Greek literature, is partly attributed to the influence of cosmogonic myths of the ancient Orient , in particular because of the close parallel to the myth of Apsu and Tiamat in the Babylonian creation myth Enûma elîsch .

Zeus alone seems to be more powerful than Oceanus , since Hypnos - according to his own statement - is able to "even put Ocean's flowing tides" but not Zeus to sleep. He is the only one who does not take part in the gathering of the gods in Olympus, to which rivers and streams are invited. It flows around the Elysion and borders the underworld . On his voyage to the underworld, Odysseus first sails through the current of the Okeanos River, and then reaches the island of Aiaia at the eastern end of the Oikumene , "where the dawning morning / apartment and dances are, and Helio's shining rise". Helios rises daily from the Ocean, only to be drowned in it in the evening; the stars also bathe in it. Okeanos is referred to as "flowing back into itself", i.e. a circular stream ( ἀψόρροος apsórroos ), which corresponds to its representation on the shield of Achilles designed by Hephaestus as an image of the world : it is the outermost edge that flows around the habitable disk of earth. In its immediate vicinity live mythical fringe peoples such as the Ethiopians and pygmies in the south, the Kimmerians in the north and monsters such as the harpies in the west.

According to Hesiod , the Gorgons , the Hesperides and Geryoneus live in the west of the Ocean . The sources of the Ocean are also located in the west by him. Nine parts of its waters flow around the world, while the Styx as the tenth part flows inside the earth to spring from the rock:

|

|

With Hesiod, Oceanus and Tethys are integrated into the genealogy of the Titans and appear as descendants of Gaia and Uranus . Their descendants are 3000 rivers and 3000 Oceanids , of which 25 rivers and 41 Oceanids are named, including important rivers such as the Nile , the Eridanos or the Phasis and, as the oldest of the Oceanids, the Styx . Okeanos clearly stands out from the rest of the titans in that he did not take part in the fall of Uranus and fought against his siblings in the Titanomachy on the side of Zeus.

The Orphic theogonies , like the theogony of Hesiods, describe a succession of rulers, but place Oceanus higher up in their genealogies. He appears there as the father of the titans and even of Uranus. With Alexander von Aphrodisias he is the successor of Chaos in second place, even before Nyx . This expresses the idea that Oceanus, as nourishing water, must be the father of all things. This view was already echoed in Homer when Hera speaks of Okeanos as the “origin of the gods” (Ὠκεανόν τε θεῶν γένεσιν) or even of the one who “gave birth to all” (γένεσις πάντεσσι).

At Pindar , Oceanus appears as both a river and a sea. The area beyond the pillars of Heracles is not passable, as darkness prevails there, the Argonauts drive through the Red Sea and the southern Ocean behind it.

Aeschylus has Oceanus fly up on a four-legged bird in his tragedy The Bound Prometheus to help Prometheus , the son of his brother Iapetus and his daughter Asia . Together they had fought against the Olympian gods in the Titanomachy until Okeanos switched to them. Okeanos does not succeed in persuading Prometheus to compromise with Zeus, which is why at the end of the scene he drifts off towards the birdhouse so that it can rest his knees. Since this representation of the Ocean does not correspond to a pictorial tradition, it is regarded as a dramaturgical invention of Aeschylus.

Family tree after Hesiod

| Gaia | Uranus | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kronos | Koios | Kreios | Oceanus | Tethys | Rhea | Mnemosyne | Themis | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Iapetos | Hyperion | Theia | Phoibe | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 3000 river gods | 3000 oceanids | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Neilos | Alpheios | Eridanos | Strymon | Admete | Akaste | Amphiro | Asia | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Maiandros | Istros | Phasis | Rhesos | Chryseis | Dione | Doris | Elektra | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Acheloos | Nessos | Rhodios | Haliakmon | Eudore | Europe | Eurynomials | Galaxaure | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Heptaporos | Granikos | Aisepos | Simoeis | Hippo | Janeira | Ianthe | Idyia | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Peneios | Hermon | Kaïkos | Sangarios | Kallirhoe | Calypso | Kerkeis | Clymene | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ladon | Parthenios | Euenos | Ardeskos | Klytia | Melite | Melobosis | Menestho | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Scamandros | Metis | Okyrhoe | Pasithoe | Peitho | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Perseis | Petraie | Plexaure | Pluto | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Polydore | Prymno | Rhodeia | Styx | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Telesto | Thoe | Tyche | Urany | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Xanth | Zeuxo | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

cult

A cult of the Ocean is not tangible, as there are only a few literary references to such a thing. It is sung about in an Orphic hymn , and Virgil mentions a sacrifice by the Cyrene . Arrian reports on cult activities of Alexander the Great as part of the Indian campaign. Before the campaign, Alexander made sacrifices to Oceanus and Tethys and then erected temples for them: one on the Indus Delta, the eastern edge of the Ocean, and one after his return on the Delta of the Nile, the origin of which was thought to be due to the Nile flood in the Ocean. Diodorus reports that Alexander sank large golden bowls as a sacrifice in the Indian Ocean (325 BC). Despite the widespread use of images on sarcophagi and other art monuments from Roman times, only a few dedicatory inscriptions from Eboracum indicate a cult of Oceanus. It is believed that these are imitations of Alexander's adoration of the Ocean after traveling to the northern edge of the Oikumene .

presentation

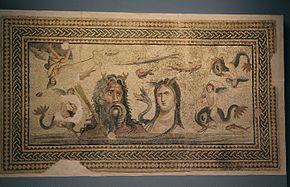

Since Okeanos does not have a fixed mythological figure and therefore the attribution of a representation can usually only be based on inscriptions, he is only rarely attested on Greek monuments. Three Attic black-figure vases from the archaic period have survived , showing Okeanos at the wedding of Peleus and Thetis both with the dragon's tail of the sea gods Nereus and Triton and with the bull horns of the river gods, which shows his dual nature as sea and river god. In the classical period he was portrayed humanely on two red-figure vases in the garden of the Hesperides . At one point he sits as the central figure with a chiton , cloak and scepter next to Strymon , surrounded by river gods and oceanids. He is marked as an old man by gray hair, otherwise without further attributes. The other time he is dressed in a himation and chiton and has a bull's horn over his forehead. Another inscription of his name can be found on a calyx crater , which, curiously, stands over a woman. As a sculpture he is preserved in human form on the Pergamon Altar, where he fights the giants with Nereus, Doris and Tethys.

On the other hand, Oceanus is a frequently encountered motif on Roman monuments. Depictions of the head on gems and bronze reliefs since the Republic and the early imperial era are part of the Hellenistic pictorial tradition, it can be seen on them with streaked or wildly curly hair and beard, the face is often covered with sea plants or the mustache becomes sea creatures at the end his head has crab claws instead of horns. This type of image became the style for all later depictions of the Oceanus head. The oldest depictions of the full body of Oceanos, such as the relief from Aphrodisias from the early first century AD or some mosaics, are also strongly influenced by the expressionist pictorial tradition of Hellenism. On them, Oceanus can be seen standing in a windblown himation or relaxed, the designs are of high artistic quality.

Overall, it can be said that his iconography is increasingly moving away from that of a deity and approaching that of a natural being, whereby he is clearly differentiated from Neptune . While Neptune with his attribute, the trident, is usually shown in action, Oceanus plays a more passive role. His attributes are the oar and anchor as a sign of a good journey as well as the attributes of the river gods, reed stalks and spring urn, since he is the father of the rivers. The use of the Oceanus head as a fountain mouth is traced back to his fatherhood of flowing waters, while the frequent appearance as a gusset ornament in the four corners of mosaics in private houses stands for the happiness of the sea, which has been considered a parable for calmness since Epicurus .

He appears on sarcophagi together with Tellus at the lower edge of the picture, where they stand as symbols for water and earth on which the mythological events take place. Starting from the sarcophagi, Oceanus and Tellus found their way into the official iconography as reclining figures on triumphal arches , coins and medallions and lived on as the embodiment of water and earth until the art of the Middle Ages.

Achilles and Cheiron , Oceanus and Tellus surround the deceased's imago clipeata , sarcophagus from the late third century AD.

Oceanus on a mosaic of the basilica in downtown Petras , late fifth century AD

Oceanus and Tellus at the bottom of the picture. Front of the cover of Cod. Sang. 53 from the St. Gallen Abbey Library . Tutilo , around 895 AD

literature

- Herbert A. Cahn : Okeanos . In: Lexicon Iconographicum Mythologiae Classicae (LIMC). Volume VII, Zurich / Munich 1994, pp. 31-33.

- Herbert A. Cahn: Oceanus . In: Lexicon Iconographicum Mythologiae Classicae (LIMC). Volume VIII, Zurich / Munich 1997, pp. 907-915.

- Hans Herter : Okeanos 1. In: Paulys Realencyclopädie der classischen Antiquity Science (RE). Volume XVII, 2, Stuttgart 1937, Sp. 2308-2361.

- Michael Janda : Elysion. Origin and development of the Greek religion. Institute for Linguistics at the University of Innsbruck, Innsbruck 2005.

- ders .: The music after the chaos. The creation myth of European antiquity. Institute for Linguistics at the University of Innsbruck, Innsbruck 2010.

- Josef Vital Kopp : The physical world view of early Greek poetry. A contribution to understanding pre-Socratic physics. Paulusdruckerei, Freiburg im Breisgau 1939, p. 55 ff. (Freiburg (Switzerland), university, dissertation, 1938).

- François Lasserre: Oceanus. In: The Little Pauly (KlP). Volume 4, Stuttgart 1972, Col. 267-270.

- Albin Lesky : Thalatta. The way of the Greeks to the sea. Rohrer, Vienna 1947, pp. 58–87.

- James S. Romm: The edges of the earth in ancient thought. Geography, exploration, and fiction. Princeton University Press, Princeton NJ 1992, ISBN 0-691-06933-6 .

- Jean Rudhardt : Le thème de l'eau primordiale dans la mythologie grecque (= Swiss Spiritual Science Society. Writings. Vol. 12, ZDB -ID 1472639-7 ). Francke, Bern 1971.

- Paul Weizsäcker: Okeanos . In: Wilhelm Heinrich Roscher (Hrsg.): Detailed lexicon of Greek and Roman mythology . Volume 3.1, Leipzig 1902, Col. 809-820 ( digitized version ).

Web links

- The Okeanos River in the Theoi Project

- The sea god Okeanos in the Theoi Project (English)

- Well mask with Okeanos: 3D model in the culture portal bavarikon

Individual evidence

- ↑ Adalbert Kuhn: ὠκεανός . In: Journal for comparative linguistic research in the field of German, Greek and Latin. Volume 9, 1860, p. 240. According to Janda, Kuhn's etymology goes back to a suggestion by Theodor Benfey ; The Swiss linguist Adolphe Pictet had the same observation shortly before in Les origines indo-européennes, ou les Aryas primitifs. Essai de paleontologie linguistique. Volume 1. Paris 1859, p. 116, published.

- ↑ a b Michael Janda: Elysion. Origin and development of the Greek religion. Institute for Linguistics at the University of Innsbruck, Innsbruck 2005, pp. 231–249; ders .: The music after the chaos. The creation myth of European antiquity. Institute for Linguistics at the University of Innsbruck, Innsbruck 2010, p. 57 ff.

- ↑ a b Attic black-figure dinosaurs of Sophilus , around 590 BC Chr. London, BM 1971.11-1.1. See the representation of the dinosaur in several detail shots on the British Museum website .

- ^ Robert SP Beekes: Etymological Dictionary of Greek . Brill, Leiden 2009, p. Xxxv.

- ↑ a b Homer , Iliad 14, 201.

- ↑ Homer, Iliad 21, 195-197.

- ↑ Homer, Iliad 18:398.

- ↑ Homer Odyssey 10, 139.

- ↑ Homer: Iliad. 14, 200-208. Translation according to Johann Heinrich Voß ( online ).

- ↑ Richard Janko, in: Geoffrey Stephen Kirk: The Iliad: A Commentary , Volume 4. Cambridge University Press 1992. pp. 180-182.

- ^ Martin Litchfield West : The east face of Helicon. West Asian elements in Greek poetry and myth . Clarendon Press, Oxford 1999. p. 148. ISBN 0-19-815221-3 .

- ↑ a b Homer, Iliad 14, 244-248.

- ↑ Homer, Iliad 20: 4-8.

- ↑ Homer, Odyssey 4, 563-569.

- ↑ a b Homer, Odyssey 11, 13-19.

- ↑ Homer, Odyssey 11, 639 f.

- ↑ Homer, Odyssey 12: 1-4.

- ↑ Homer, Iliad 7, 421 f .; 8, 485; 18, 239 ff.

- ↑ Homer, Iliad 5: 5; 18, 489.

- ↑ Homer, Iliad 18:39; Odyssey 20, 65.

- ↑ Homer, Iliad 18, 607 f.

- ↑ Homer, Iliad 1, 423 f.

- ↑ Homer, Iliad 3, 5 f.

- ↑ Homer, Iliad 16,150.

- ↑ Hesiod, Theogony 274 f.

- ↑ Hesiod, Theogony 292 ff.

- ↑ Hesiod, Theogony 287 ff.

- ↑ Hesiod, Theogony 282.

- ^ Hesiod, Theogonie 775 ff. Translation by Heinrich Gebhardt, edited by Egon Gottwein ( based on Navicula Bacchi ).

- ↑ Hesiod , Theogony 132 f.

- ↑ Hesiod, Theogony 337-370.

- ↑ Libraries of Apollodorus 1, 3.

- ^ Hesiod, Theogony 398.

- ↑ Plato , Timaeus .

- ↑ Etymologicum genuinum , sv Ἄκμων .

- ↑ Alexander von Aphrodisias , Commentary on the Metaphysics of Aristotle , 821.

- ^ François Lasserre: Oceanus . In: The Little Pauly . Volume 4, Stuttgart 1972, Col. 267.

- ↑ Pindar , fragments 30 (6) 6; 326 (220).

- ↑ a b Pindar, Pythien 4, 251.

- ^ Pindar, Olympia 3, 44.

- ↑ Pindar, Nemeen 3, 21, 4.

- ↑ Aeschylus , The Fettered Prometheus 284–287.

- ↑ Aeschylus, The Fettered Prometheus 330 f.

- ↑ Aeschylus, The Fettered Prometheus 394–396.

- ^ Herbert A. Cahn : Okeanos . In: Lexicon Iconographicum Mythologiae Classicae . Volume VII, Zurich / Munich 1994, p. 31.

- ↑ Orphic Hymn 83.

- ^ Virgil , Georgica 4, 381.

- ↑ So with clear criticism already in Herodotus , Historien II, 21 ff.

- ^ Arrian , Indike 18:11 .

- ↑ Arrian, Anabasis 6:19 , 4.

- ^ Diodorus 17, 104, 1.

- ↑ Supplementum Epigraphicum Graecum 29, 1029; 38, 1042; 53, 1156.

- ↑ Alexandre Nicolas Oikonomides, in: The Ancient World , Volume 18. Chicago 1988, pp. 31-34.

- ↑ Attic black-figure dinosaurs (fragments) of Sophilus, around 590 BC BC Athens, NM Akr. 587.

- ^ Françoisvase , around 570 BC Next to the inscription only a horn and part of the tail are preserved.

- ↑ Attic red-figure pointed amphora by the Pistoxenus painter , around 480–470 BC. Chr. Private property.

- ↑ Attic red-figure pelike by the Pasithea painter , around 380 BC. Chr. New York MMA 1908.258.20.

- ↑ Attic red-figure calyx crater of Syriskos , around 470 BC. BC Getty Museum 92.AE.6.

- ^ Herbert A. Cahn: Okeanos . In: Lexicon Iconographicum Mythologiae Classicae . Volume VII, Zurich / Munich 1994, p. 33.

- ↑ Karl Schefold : The meaning of the Cretan sea images . In: Antike Kunst Vol. 01, Issue 1. Basel 1958. S. 5.

- ^ Herbert A. Cahn: Oceanus . In: Lexicon Iconographicum Mythologiae Classicae . Volume VIII, Zurich / Munich 1997, p. 914 f.