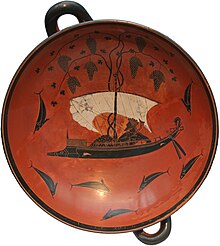

Red-figure vase painting

The red figure vase painting (also red figure pottery , red figure style ) is one of the most important styles of figurative Greek vase painting . It was made around 530 BC. In Athens and was in use until the end of the 3rd century BC. In the course of a few decades, it replaced the previously predominant black-figure vase painting . It got its modern name because of the figurative representations in red on a black background, which it sets it apart from the older black-figure style with black figures on a red background. The most important production areas, besides attica, were Lower Italian-Greek workshops. In addition, the red-figure style was adopted in other areas of Greece. Etruria was an important production site outside of the Greek cultural area .

Attic red-figure vases were exported to all of Greece and beyond and dominated the fine ceramics market for a long time. Only a few production facilities could compete with the innovation, quality and production capacity of Athens. Of the red-figure vases produced in Athens alone, well over 40,000 copies are still preserved in whole or in fragments. More than 20,000 vases and fragments have also come down to us from the second important production facility, southern Italy. Since the studies of John D. Beazley and Arthur D. Trendall , beginning in the first quarter of the 20th century, the study of this art form has advanced well. Many vases can be assigned to specific artists or artist groups. The imagery of the vases is indispensable for studies of cultural history, everyday life, iconography and mythology of ancient Greece.

technology

The red-figure technique was - to put it simply - the reverse of the black-figure technique. The outline drawings of the figures and other parts of the picture were applied to the still unbaked, leather-hard, almost brittle vase bodies after drying for a while. The normal unfired clay had an orange-red hue during this production step, for example in Attika. The outlines were either drawn with a blunt instrument, which left slight furrows, or with charcoal, which later disappeared during the fire. Then the contours were traced with a brush and gloss shade. Sometimes, thanks to the furrows in the preliminary drawings, you can still see if the artist decided to change the representation a little while drawing. A slightly raised relief line made of applied clay slip was used for important contours, a thinned gloss tone was sufficient for less important lines and interior drawings. Other colors such as white or red have now also been applied for details. A bristle brush was probably used to apply the line in relief. The strong application as a relief line was necessary, as the rather fluid glossy shade would otherwise have created a matt effect. After an initial development phase, both options were used in order to be able to better represent gradations and details. The space between the figures was last covered with a matt gray gloss shade. Then the vases were fired in a three-phase fire. The gloss tone got its characteristic black to black-brown color.

The new technology had the advantage that the interior drawings could now be worked out much better. In the black-figure style, they had to be scratched out of the application of paint, which was inevitably less precise than the direct application of decorative lines. The red-figure depictions were more moving and closer to life than the black-figure silhouette style. They also stood out more contrasting against the black background. It was now possible to show people not only in profile, but also from the front, from behind or in three-quarter views. The red-figure technique also allowed the mediation of depth and space. But it also had disadvantages. The usual black-figure style differentiation of the sexes by covering the female skin with white paint was no longer possible. It also became more difficult to differentiate between the sexes based on their robes or hairstyles, which was partly due to the tendency to depict many heroes and gods as youthful, i.e. beardless. In addition, especially in the early days of the style, there were miscalculations in figure thickness. In the black-figure vase painting, the outlines belonged to the free-standing figures. Since the outline drawings were now made in the color of the black background, the outlines had to be counted against the background with which they finally merged. That's why there were often very thin figures at first. Another problem was that it was not possible to show the depth of the room with the black background. Thus, in the case of red-figure vase painting, an attempt was almost never made to depict it in perspective. But the advantages outweighed them. The development can be followed using examples, especially in details such as muscles or other anatomical features.

Attica

In the 7th century BC Black-figure vase painting was developed in Corinth in BC , which was to become the predominant design method in the Greek settlement area and was even widespread beyond that. Corinth dominated this market, but regional production centers and markets developed. In Athens, the Corinthian style was first copied. Over time, Athens replaced Corinth in the dominant position. The Attic artists took the technique to a hitherto unheard of level and in the second third of the 6th century B.C. Their possibilities to the full. Around 530 BC BC, the Attic painter Exekias was probably the most important representative of the black-figure style. Also through the 5th century BC Throughout BC, the fine ceramics from Attica, produced in the new red color style, were the dominant products in this branch of the economy. Attic pottery was exported to the whole of Great Greece , even to Etruria and Celtic Central Europe. The preference for this pottery resulted in workshops and "schools", which were influenced by Attic vase painting, especially in southern Italy and Etruria, but which produced exclusively for the regional market.

Beginnings

Around 530 BC Vases in the red-figure style were first produced. The Andokides painter is generally considered to be the inventor of this technique . He and other very early exponents of the new style, such as Psiax , initially painted vases in both styles by using the black-figure technique on one side and the red-figure technique on the other. Such vessels, such as the abdominal amphora of the Andokides painter in Munich , are called bilinguals . In comparison to the black-figure style, great progress could already be seen, but the figures still appeared stiff and there was seldom overlapping of the image content. Many old style techniques were still used in their manufacture. So often find scoring lines or additional order red paint ( added red ), were colored with the larger areas of color.

Pioneering time

The artists of the so-called pioneer group took the step towards exhausting the possibilities of red-figure painting . Their period of activity is approximately in the years between 520 and 500 BC. Dated. Important representatives were Euphronios , Euthymides and Phintias . This group, tapped and defined by research, experimented with the various possibilities of the style. The figures shown appeared in new postures with back and frontal views, there were experiments with foreshortening and the compositions became more dynamic overall. Euphronios probably introduced the relief line as a technical innovation . In addition, new vessel shapes were developed, which was favored by the fact that many painters in the pioneer group also worked as potters. The Psykter and the Pelike were new . In addition, large format craters and amphorae were preferred. Although the group had no real cohesion, there were connections between the individual painters, who obviously influenced one another, found themselves in a kind of friendly competition and encouraged one another. Euthymides boasted in an inscription "as [it] Euphronios never [could]" . In general, it is a sign of the pioneer group that they were very fond of writing. Identifications of the represented mythological figures and Kalos inscriptions were more the rule than the exception.

In addition to the vessel painters, several important bowl painters also worked with the new style. Oltos and Epiktetos belonged to them . They decorated many of their works bilinge, then mostly used the red-figure technique for the inside of the bowls.

Late archaic

The generation of late Archaic artists following the pioneers (around 500 to 470 BC) led the new style to blossom. The black-figure vases that were still produced at that time were no longer of comparable quality and were almost completely displaced. Some of the most important vase painters worked at this time. Among the vessel painters , the Berlin painter and the Cleophrades painter should be mentioned , while Onesimos , Duris , Makron and the Brygos painter stood out among the bowl painters . Not only did the quality keep improving, production also doubled during this time. Athens became the dominant producer of fine ceramics in the Mediterranean world, almost all regional productions outside Attica came into its shadow.

Characteristic for the success of the Attic vases was the now perfectly mastered foreshortening, which made the represented figures appear far more natural in their postures and actions. In addition, there was a massive reduction in what was represented. Ornamental decorations faded into the background, the number of figures depicted was significantly reduced, as were the anatomical details depicted. In return, many new themes were introduced into vase painting. The saga about Theseus was particularly popular . New or modified vessel shapes were gladly adopted by the painters, including the Nolan amphora , lekyths , type B bowls, askoi and dinoi . There is also an increasing specialization of vessel and vase painters.

Early and high classics

The special feature of early classical figures was that they were often more stocky than with earlier painters and no longer appeared as dynamic. As a result, the pictures often appeared serious, sometimes even pathetic. The folds of the robes, on the other hand, were no longer so linear and now looked more plastic. In addition, the type of presentation changed permanently. On the one hand, the moment of a certain event was often no longer shown, but the situation immediately before it and thus the way to an occurrence. On the other hand, other new achievements of the Athenian democracy began to show their effects. Influences of the tragedy and the wall painting can be determined. Since Greek wall painting is almost completely lost, the reflexes in vase painting are an - albeit modest - tool in researching this art form. For example, the newly created Parthenon and its sculptural furnishings also influenced vase painters of the high class. This was particularly reflected in the depiction of the robes. The fall of the fabric now looked more natural and the reproduction of folds was increased, which led to a greater depth of representation. Image compositions have been simplified again. The artists placed particular emphasis on symmetry, harmony and balance. The now slimmer figures often exuded a sunk, godlike calm.

Important artists of the early and high classical period from around 480 to 425 BC Are the Providence Painter , Hermonax and the Achilles Painter , who continued the tradition of the Berlin painter. The Phiale painter , who is considered a pupil of the Achilles painter, is also one of the most important artists. In addition, new workshop traditions emerged. The so-called "Mannerists", whose outstanding representatives were the Pan-Painter , were particularly important . Another workshop tradition began with the Niobid Painter and was continued by Polygnotos , the Cleophon Painter and the Dinos Painter . The importance of the bowls declined, although they were still produced in large quantities in the workshop of the Penthesilea painter , for example .

Late Classic

During the late classical period , from the last quarter of the 5th century BC onwards, Two opposing currents. On the one hand, a direction based on the “ rich style ” of sculpture developed, and on the other hand, developments from the high classics were retained. The most important representative of the rich style was the Meidias painter . Characteristic features are translucent robes and a large number of creases. In addition, jewelry and other objects are increasingly shown. The use of other colors, mostly white or gold, which emphasize accessories reproduced in relief, is particularly striking. This was the first time an attempt was made to create a three-dimensional representation on vases. In the course of time, a "softening" set in. The male body, which was previously mainly defined by the representation of muscles, has lost this striking feature.

The scenes depicted were now also less often devoted to mythological topics than before. Pictures from the private world gained in importance. Representations from the world of women are particularly common. In mythological scenes, images with Dionysus and Aphrodite dominate . It is not exactly known why this change in the method of representation began with some of the artists. On the one hand a connection with the horrors of the Peloponnesian War is assumed, on the other hand it is attempted to explain the loss of Athens' dominant position on the Mediterranean pottery market, which would ultimately have been a consequence of the war. Now new markets should have been opened up, for example in Spain, where customers had different wishes and needs. These theories are contradicted by the fact that the old style was retained by some artists. Other artists, like the Eretria Painter , tried to combine the two styles. The best works of the late classical period can be found on small-format vase types such as abdominal lycotha, pyxides and oinochoa . The lekanis , the bell crater and the hydria were also popular .

Around 370 BC The production of the usual red-figure ceramics ends. Both the Rich and the Plain styles continued to exist until then. The most important representative of the rich style at this time was the Meleager painter , that of the simple style was the last important bowl painter , the Jena painter .

Kerch vases

The last decades of red-figure vase painting in Athens were shaped by Kerch vases . The style they represent, which dates from around 370 to 330 BC. BC was dominant, formed a combination of the rich and the simple styles, with the rich style having a greater influence. Typical for the Kerch vases were overloaded pictorial compositions with large, statuesque figures. In addition to the previously common additional colors, blue, green and others are now also being added. In order to show volume and shadow, a thinned, gradual gloss shade is applied. Sometimes whole figures are applied , that is, placed on the body of the vase as small figural reliefs. The number of different vessel shapes is falling sharply. The usual image carriers now were peliks , calyx craters , belly lecitha, skyphoi, hydria and oinochoa. Scenes from the lives of women were shown in particularly large numbers. Dionysus continued to dominate mythological images, as did Ariadne and Heracles among the heroes. The most important artist is the Marsyas painter .

At the latest by 320 BC. The last vases with figurative representations were created in Athens. After that, vases were made using this technique for some time, but they were decorated in a non-figurative manner. The last tangible representatives are the painters of the group named YZ .

Artists and works

The pottery district of Athens was the Kerameikos . There were various smaller and probably larger workshops here. In 1852 the workshop of the Jena painter was found during construction work on Hermesstrasse . The artifacts found there are now in the university collection of the Friedrich Schiller University Jena . According to today's knowledge, the owners of the workshops were the potters. The names of about 40 Attic vase painters are known from inscriptions. The name generally included the addition ἐγραψεν (égrapsen, has painted ). On the other hand there was the signature of the potters, ἐποίησεν (epoíesen, made ) which was found more than twice as often, namely about 100 times. Had the signatures been around since around 580 BC? Known in BC, their use increased to a peak during the pioneering days. But with a changed, more negative attitude towards the handicraft, the number of used signatures decreased again over the course of time, at least since the Classical period. Overall, however, such signatures are quite rare and since they were often found on particularly good pieces, they certainly show the pride of the potters and vase painters.

The status of painters in comparison with potters is sometimes unclear. Since, for example, Euphronios and other painters later worked as potters themselves, it can be assumed that at least a considerable part were not slaves. But some names suggest that the vase painters also included former slaves or Periöks . In addition, some of the well-known proper names cannot be clearly interpreted. There are several vase painters who signed as Polygnotos . These are probably attempts to benefit from the name of the great monumental painter. The same could be the case with other painters with famous names, such as Aristophanes . Some of the careers of vase painters are well documented today. In addition to painters who only worked for a relatively short period of time, one to two decades, there were also painters whose creative period can be traced for much longer. These long-acting artists include, for example, Duris , Makron , Hermonax or the Achilles painter . Since the change from painter to potter can be observed several times, and it is often unclear whether some potters also worked as painters and vice versa, it is assumed that a career from assistants, who were responsible for painting the vases, for example, to to the potter was possible. With the introduction of red-figure painting, however, the work pattern of potters and vase painters apparently only changed to this division of labor. Many Attic pottery painters are known even during the black-figure period, such as Exekias, Nearchus or possibly Amasis . Due to the increased export demand, restructuring in the production process became necessary, division of labor became common and a not always clear separation between potter and vase painter was implemented. As already mentioned, the painting of the vessels was probably mainly the responsibility of the younger assistants. Now some pointers can be made about the possibilities of the craft groups. It seems that in general several painters have worked in a pottery workshop, because there are often works by different vase painters by one potter painted at a similar time. For example, Onesimos , Duris, the Antiphon Painter , the Triptolemus Painter and the Pistoxenus Painter worked for Euphronios . On the other hand, the painters could also switch between the workshops. The bowl painter Oltos worked for at least six different potters.

Even if vase painters are often viewed as artists from today's perspective and the vases are accordingly works of art, this does not correspond to the ancient view. Vase painters, like potters, were artisans, and their products were commodities. The craftsmen must have had an appropriate level of education, as other inscriptions and inscriptions can often be found. On the one hand there are the already mentioned Kalos inscriptions (also called favorite inscriptions), on the other hand there are inscriptions of the sitter. But not every vase painter could write, as some examples of meaninglessly lined up letters show. But it can be observed that literacy has been increasing since the 6th century BC. Chr. Steadily improved. It has not yet been possible to satisfactorily clarify whether potters and vase painters were among the Attic elite: if the painters represented scenes from the symposium, a pleasure for the upper class, they themselves longed to participate or simply satisfied a need for goods ? A large part of the vases produced such as Psykter, Kratere, Kalpis and Stamnos, but also Kylixes and Kanthares, were intended at least for this purpose, the symposium.

Elaborately painted vases were good, but not the best tableware a Greek could own. Metal dishes, especially made of precious metal, of course, were more prestigious than such vases. Still, such vases weren't exactly cheap products. Large specimens were especially valuable. Large painted vessels cost around 500 BC. About one drachma , which corresponded to the daily wage of a stonemason at the time. On the other hand, the ceramic vessels can also be interpreted as an attempt to imitate metal dishes. It can be assumed that the lower social classes tended to use simpler utility ceramics that have been extensively proven in excavations. Crockery made from perishable materials such as wood was probably even more common. Nevertheless, numerous settlement finds of red-figure ceramics, albeit not of the highest quality, show that these vessels were used in everyday life. A large part of the production, however, was reserved for cult and grave vessels. In any case, it can be assumed that the production of high-quality pottery was a profitable business. For example, the remains of an expensive consecration gift from the painter Euphronios were found on the Acropolis of Athens. There is no doubt that the export of ceramics played a part in the prosperity of Athens that should not be underestimated. It is therefore not surprising that many workshops geared their production towards export and, for example, made vessel shapes that were in demand in the customer regions. The decline of vase painting began not least in the time when the Etruscans, probably the main buyers of Attic ceramics, in the 4th century BC. BC came under increasing pressure from southern Italian Greeks and the Romans. Especially since the defeat of the Etruscans against the Greeks in 474 BC. BC imported these much less Greek ceramics and increasingly produced them themselves. After that, Attic traders exported mainly within the Greek world. The main reason for the decline, however, was the increasingly poor course of the Peloponnesian War for Athens, which resulted in the devastating defeat of the Athenians in 404 BC. Culminated in BC. From now on Sparta controlled trade with Italy without having the economic strength to fulfill it. Attic potters had to look for a new market and found it on the Black Sea, in Spain and in southern France. These vases are mostly of lower quality and were bought mainly because of their "exotic flair". However, Athens and the pottery industry never fully recovered from the defeat and during the war some potters and vase painters moved to southern Italy, where the economic basis was better. Characteristic of the focus of Attic vase production on export is the almost complete renunciation of the pictorial representation of theater scenes. Because buyers from other cultures, such as Etruscans or later buyers in today's Spain, would not have understood the depictions or found them interesting. In the sub-Italian vase painting, which is not aimed at export, however, vases with pictures from the theater sector are not uncommon. Another reason for the end of production of figuratively decorated vases was a change in taste that began with the beginning of the Hellenism .

Lower Italy

The Lower Italian red-figure vase painting comes from a production area that, from a modern point of view, was the only one able to keep up with the Attic productions from an artistic point of view. After the Attic vases, the Lower Italian ones, which also include the Sicilian ones, are the best explored. In contrast to their Attic counterparts, they were mainly produced for the regional market. Only a few pieces were found outside of southern Italy, the coastal region of which was controlled at the time by Greek cities founded during Greek colonization . The first workshops emerged in the middle of the 5th century BC. They were founded by Attic ceramists. Local craftsmen were quickly trained and the thematic and formal dependence on Attic vases was soon overcome. Towards the end of the century, the so-called ornate and plain styles emerged in Apulia . Above all, the ornate style was adopted by the other mainland schools, but it was never brought to Apulian craftsmanship there.

Today about 21,000 Lower Italian vases and fragments are known. Of these, about 11,000 were assigned to the Apulian, 4000 to the Campanian, 2000 to the Paestan, 1500 to the Lucanian and about 1000 to the Sicilian workshops.

Apulia

The Apulian Ceramics is considered the leading genus of South Italian Ceramics. An important production center was in Taranto . The red-figure vases were made in Apulia from about 430 to 300 BC. Manufactured. In Apulian vase painting, a distinction is made between the plain and the ornate style . The main reason for the difference is that in the plain style , apart from bell and column craters , smaller vessels were painted. These rarely show more than four figures. The focus in the depiction were mythological themes, female heads, warriors in battle and farewell scenes as well as Thiasos images from the Dionysian realm. On the back, “ young men in the cloak ” were often depicted. The most important feature of these simply decorated and composed vases is that they do not use any additional colors. The Sisyphus Painter and the Tarporley Painter were important representatives . After the middle of the fourth century BC, an approach to the ornate style can be observed. The most important artist at this time was the Varrese painter .

In the ornate style , the artists mostly attached importance to large-format vases such as volute craters , amphorae, loutrophores and hydrates. The larger surface of the vessel was used to represent up to 20 figures in several registers on the body of the vase. Additional colors, especially shades of red, golden yellow, and white, were used abundantly. Since the second half of the 4th century BC Above all in the neck areas and on the sides of the vases, lush plant or ornamental decorations were applied. At the same time perspective views, especially of buildings such as the “Underworld Palaces” ( Naïskos ), were shown. Since around 360 BC Such buildings were often depicted in scenes related to the cult of the dead ( Naïskos vases ). The most important representatives of this style are the Iliupersis Painter , the Darius Painter and the Baltimore Painter . Mythological scenes were especially popular: meetings of gods, Amazonomachies , the Trojan saga , Heracles and Bellerophon . In addition, myths were depicted again and again that are otherwise rarely seen on vases. Some vases are the only source for the iconography of such myths. The theatrical representations are a rare subject in Attic painting. Above all, antiquity scenes, for example on so-called phlyak vases , are not uncommon. Depictions of everyday life and sports only played a role in the early days, after 370 BC. They disappear from the repertoire. Many of the differences to Attic vase painting can be traced back to the fact that the Apulian vessels were increasingly made specifically for their use on and in the grave.

Apulian painting influenced the other ceramic centers in Lower Italy significantly. It is believed that some Apulian artists had settled in other sub-Italian cities and brought their skills there. In addition to the red-figure vases, black-glazed vessels with painted decorations ( Gnathia vases ) and polychrome vases ( Canosiner vases ) were also produced in Apulia .

Campania

Also in Campania in the 5th and 4th centuries BC. Chr. Red-figure vases created. A coating was applied to the light brown shade of Campania, which after firing takes on a pink to red hue. Campanian vase painters preferred rather smaller types of vessels, with hydration and bell craters added. As a leading form of Campania which applies Bügelhenkelamphora . Many vessel shapes that were typical of Apulian pottery were missing, such as volute and colonic craters, lutrophores, rhyta and nestorids ; Peliks are rare. The motivic repertoire is limited. On display are figures of young men and women, Thiasos scenes, pictures of birds and animals, especially local warriors and women. Often there are cloak boys on the back. Mythological scenes and representations related to the grave cult play a subordinate role. Naiskos scenes, ornamental elements and polychromy are only used from around 340 BC. Taken up under Apulian influence.

Before the immigration of Sicilian ceramists in the second quarter of the 4th century BC BC, who established several workshops in Campania, there is only the workshop of the Owl-Pillar group from the second half of the 5th century BC. Known. Campania vase painting is divided into three main groups:

The first group is represented by the workshop of the Cassandra painter from Capua , who was still under the influence of Sicilian painters. It is followed by the workshops of the Parrish painter and the workshop of the Laghetto painter and the Caivano painter . Characteristic are the preference for Satyrfiguren with Thyrsos , representations of heads - usually below the handles of hydriai -, tin border white on the robes and the frequent use, red and yellow additional color. The Laghetto and Caivano painters appear to have emigrated to Paestum later .

The AV group also had its workshop in Capua. The Whiteface Frignano painter , who was one of the first painters of the group, is particularly important here . Typical for him is the use of additional white color to mark female faces. Local scenes, women and warriors were shown especially in this group. Multi-figure scenes are rare, usually only one figure is shown on the front and back, sometimes only the head. The robes are mostly sketchy.

In Cumae worked after 350 BC. The CA painter as well as his employees and successors. The CA painter is considered to be an outstanding representative of this group, possibly of all Campanian vase painting. From 330 BC A strong influence of Apulian vase painting is evident. The most common motifs are naiskos and grave scenes, Dionysian scenes and symposium representations. The depiction of decorated women's heads is also typical. The CA painter worked in polychrome, but sometimes used a lot of opaque white in depictions of architecture and women. His successors were only able to maintain its quality to a limited extent and so it quickly began to decline, which began around 300 BC. BC also led to the end of Campanian vase painting.

Lucania

The Lucanian vase painting began around the year 430th With the work of the Pisticci painter . He probably worked in Pisticci , where some of his works were found. He was still strongly in the Attic tradition. His successors, the Amykos Painter or the Cyclops Painter , had their workshop in Metapont . They were the first to paint the new Nestoris type of vase. Often mythical scenes and images from theater life are shown. The Cheophoroi painter, named after the Cheophoroi of Aeschylus , showed scenes from this tragedy on several of his vases. At this time, the influence of Apulian vase painting can also be felt. Above all, the polychromy and ornamental plant decorations are now standard. Important representatives at this time were the Dolon Painter and the Brooklyn-Budapest Painter . To the middle of the 4th century BC A massive decrease in quality and thematic diversity can be observed in the representations. The last important vase painter in Lucania was the Primato painter, influenced by the Apulian Lycurgus painter . According to him, Lukan vase painting ends after a brief rapid decline at the beginning of the last quarter of the 4th century BC. Chr.

Paestum

The paestan vase painting was the last South Italian style. It was made around the year 360 BC. Founded by Sicilian inhabitants. The first workshop was run by Asteas and Python . They are the only two vase painters in southern Italy who are known by name from inscriptions. Above all, bell craters, neck amphorae, hydriai, Lebetes Gamikoi , Lekaniden , Lekythen and pitchers were painted; pelicas, goblet craters and volute craters were used less frequently. Particularly characteristic are decorations such as palmettes on the side , a tendril known as the "Asteas flower" with a calyx and umbel , crenellated patterns on the robes and curly hair hanging down over the back. Figures that lean forward and lean on plants or stones are also typical. Auxiliary colors are often used, especially white, gold, black, purple, and various shades of red.

The subjects depicted are often located in the Dionysian range: Thiasos- and symposia scenes, satyrs and maenads , Papposilenen and Phlyakenszenen . Numerous other mythical motifs are also represented, above all Heracles, the Paris judgment , Orestes , Elektra , among the gods Aphrodite and Eroten , Apollo, Athena and Hermes. In Paestan painting there are only seldom everyday pictures, but depictions of animals. Asteas and Python had a lasting influence on the city's vase painting. This can be seen in the work of their successors, such as the Aphrodite painter who probably immigrated from Apulia . Around 330 BC A second workshop was built, which was initially based on the work of the first. But the quality and richness of motifs of the work quickly deteriorated. At the same time, the influence of the Campanian Caivano painter can also be seen. The result was linear garment contours and contourless female figures. Around 300 BC The Paestanic vase painting came to a standstill.

Sicily

The production of Sicilian vases began before the end of the 5th century BC. In the cities of Himera and Syracuse . The workshops based their work on the Attic models in terms of style, theme, ornaments and vase shapes. Above all, the influence of the Attic-late classical Meidias painter is recognizable. In the second quarter of the 4th century BC Ceramists who emigrated from Sicily to Campania and Paestum established the production facilities there and only in Syracuse was there a limited vase production.

The typical Sicilian vase painting was only created around 340 BC. We can distinguish three workshop groups. A first group, called Lentini-Manfria , was active in Syracuse and Gela , a second group on Etna ( Centuripe genus ) and the third group on Lipari . The use of additional colors, especially white, is particularly typical of Sicilian vase painting. Especially in the initial phase, large vessels such as calyx craters and hydria are painted, but smaller vessels such as bottles, lekans, lekyths and skyphoid pyxids are typical. Above all, scenes from the world of women, erotes, women's heads and phlyacs are shown. Mythical content is rare. As in all other areas, around 300 BC marks the year. The end of Sicilian vase painting.

Other Greek areas

In addition to the Attic and Lower Italian red-figure vase painting, unlike the black-figure style, hardly any significant regional traditions, workshops or even “schools” could develop. In Greece, workshops were nevertheless set up in Boeotia , Chalkidike , Elis , Eretria , Corinth and Laconia .

Boeotia

Boeotian vase painting in the red-figure style had its heyday in the second half of the 5th and the first decades of the 4th century BC. The potters tried to imitate Attic vases with a reddish coating. This was necessary because the tone of Boeotia was lighter, about leathery yellow. The varnish used is brown-black. The inscriptions were mostly incised. The figures lack the three-dimensional depth of the Attic models. In addition, there is no real development in Boeotian painting; there were simply attempts to copy the Attic forms of representation. The most important artists were the painter of the Paris judgment , who was mainly based on Polygnotos and the Lycaon painter , the painter of the Athenian Argos Cup , who is reminiscent of the Shuvalov painter and the Marlay painter , and the painter of the great Athenian Kantharos . The latter is so close to the Attic dinosaur painter that he may have been trained by him.

Corinth

The red-figure vase painting of Corinth was recognized by Adolf Furtwängler in 1885 . The vases were made from a clay that was finer than the attic and pale yellow in color. The matt varnish does not shine and does not adhere well to the clay background, which is why another reddish clay coating was often applied, on which the color held better. To a small extent, these vases were also traded outside of Corinth. Corinthian red-figure vases were also found in Argos, Mycenae , Olympia and Perachora . Production continued around 430 BC. And ended around the middle of the 4th century BC. BC. The first pictures seem very simple because the painters have not yet mastered the technique well enough. There were problems with the representation of anatomical details and of faces in three-quarter view. From around 400 BC. The Corinthian painters mastered the technique at a good level. In contrast to their Attic colleagues, they never used additional gold paint, opaque colors, or image compositions with several levels. No signatures have been found so far. Currently, around half of the vases and fragments found can be assigned to six artists. The three most important painters are the Peliken Painter , the Hermes Painter and the Sketch Painter . Symposia and Dionysian pictures as well as athletes are shown. Mythical representations and pictures from the domestic area are very rare. It is unclear why it took about 100 years from the invention of red-figure vase painting to the start of production in Corinth. The import from Attica did not stop despite the Peloponnesian War. Production may have been necessary because of isolated delivery problems due to the war. However, certain vase and picture forms were required in the religious and sepulcral framework and therefore had to be available at all times.

Etruria

In Etruria, one of the main buyers of Attic vases, on the other hand, schools and workshops developed that did not only produce for the local market. However, an imitative adoption of the red-figure style did not take place until around 490 BC. BC and thus almost half a century after its development. These early products are known as pseudo-red-figure Etruscan ceramics because of their painting technique. Only towards the end of the 5th century BC The real red-figure technique was also introduced in Etruria. Numerous painters, workshops and production centers were found for both styles. The products were not only produced for the local market, but also sold to Malta , Carthage , Rome and the Ligurian coast .

Pseudo-red-figure vase painting

In early vessels of this style, the red-figure painting technique was only imitated. As with many early Attic vases, the entire body of the vessel was covered with black gloss and the figures were subsequently painted with red oxidizing or white earth colors. In contrast to the simultaneous Attic vase painting, the red-figure effect was not achieved by leaving out the painting ground. As in the black-figure vase painting, the interior drawings were then replaced by incisions and not additionally painted on. Important representatives of this painting style were the Praxias painter and other masters in his workshop in Vulci . Despite an obviously good knowledge of Greek mythology and iconography - which, however, were not always precisely implemented - there is no evidence that the workshop masters had immigrated from Athens. Only in the case of the Praxias painter, painted inscriptions in Greek on four of his vases suggest that they came from Greece.

The pseudo-red-figure style was not a phenomenon of the early days in Etruria, such as in Athens. Especially in the 4th century BC Some workshops specialized in this technique, although at the same time real red-figure vase painting was widespread in Etruscan workshops. Mention should be made of the workshops of the Sokra and Phantom groups . The somewhat older Sokra group preferred bowls, the interior of which offered depictions of mythical themes from the Greeks, but also Etruscan content. Motifs of the phantom group mostly depicted cloak figures in combination with compositions of plants and palmettes. The associated workshops of both groups are believed to be in Caere , Falerii and Tarquinia . The Phantom Group produced their goods until the early 3rd century BC. Chr. The changing tastes of the buyer classes bring the end of this style as well as for the red-figure vase painting in general.

Red-figure vase painting

Only towards the end of the 5th century BC The real red-figure painting technique with recessed clay-ground figures was introduced in Etruria. The first workshops were built in Vulci and Falerii, which also used this technique to produce for the surrounding area. Attic masters were probably behind the establishment of the first workshop, but sub-Italian influence can also be demonstrated on the early vessels. Until the 4th century BC These workshops dominated the Etruscan market. Mostly mythological scenes were depicted on large to medium-sized vessels such as craters and jugs. In the course of the century, Faliscian production began to outnumber that of Vulci. New production centers were established in Chiusi and Orvieto . Above all, Chiusi with his drinking bowls from the Tondo group , which mostly represented Dionysian themes in the inner bowl, gained in importance. In the second half, production relocated to Volterra. Above all, bar handle craters , so-called Keleben , were made and initially painstakingly painted.

In the second half of the 4th century BC The mythological themes disappeared from the repertoire of Etruscan vase painters. In their place were female heads or figurative representations of at most two people. Instead, ornaments and floral motifs spread across the bodies of the vessels. Only in exceptional cases do large compositions return, such as the Amazonomachy on a crater by the The Hague Funnel Group painter . The initially extensive production of Faliscian vessels lost its importance to the newly established production center in Caere. Probably founded by Faliski masters and with no independent tradition, Caere became the dominant manufacturer of red-figure vases in Etruria. Simply painted oinochoes, lekyths, drinking bowls from the Torcop group and small plates from the Genucilia group were part of the standard repertoire of their production. With the production changeover to black varnish vases at the end of the 4th century BC BC, which corresponded to the taste of the time, the red-figure vase painting also came to an end in Etruria.

Exploration and reception

To this day, well over 65,000 red-figure vases and vase fragments have become known, hundreds are added every year, and an unknown number of vases is still unpublished today. Already in the Middle Ages people began to deal with antique vases and Greek vase painting. Ristoro d'Arezzo dedicated the chapter Capitolo de le vasa antiche in his description of the world to the antique vases . He found the clay vases in particular to be perfect in terms of shape, color and drawing. But the focus was initially on the vases in general, or rather on the stone vases. The first collections of antique vases, which also included painted vessels, were created during the Renaissance . There are even known imports of Greek vases to Italy. However, until the end of the Baroque era , painted vases were in the shadow of other genres, such as sculpture in particular . An exception from the time before Classicism was a book with watercolors of picture vases, commissioned by Nicolas-Claude Fabri de Peiresc . Like several other collectors, Peiresc owned clay vases himself.

Ceramic vessels have also been collected more and more since classicism. William Hamilton and Giuseppe Valletta , for example, owned vase collections. Hamilton even owned two collections of antique vases during his life. The first became the basis of the British Museum's vase collection, while the second collection was published by Johann Heinrich Wilhelm Tischbein and his students. Vases found in Italy were affordable even for smaller budgets and therefore private individuals were also able to amass remarkable collections. Vases were a popular souvenir from young European travelers from their Grand Tour . Even Johann Wolfgang von Goethe reported in his Italian Journey of 9 March 1787 by the temptation to buy antique vases. Those who couldn't afford originals had the option of purchasing copies or engravings. There were even factories that imitated antique vases. The best known here is the Wedgwood ware , which however had nothing in common with the production method of Greek vases and only used antique motifs as a thematic template.

Since the 1760s, archaeological research has also increasingly devoted itself to vase painting. It was valued as a source for all areas of ancient life, especially for iconographic and mythological studies. Vase painting was now taken as a replacement for the almost completely lost Greek monumental painting. Around this time, the long-held view that the painted vases were Etruscan works could no longer be maintained. Nevertheless, the antique vase fashion of the time was called all'etrusque . England and France tried to outdo each other in both research and imitation of the vases. With Johann Heinrich Müntz and Johann Joachim Winckelmann , representatives of the "aesthetic literature" dealt with vase painting. Winckelmann in particular appreciated the "outline style". Various vase ornaments were collected and distributed in so-called pattern books in England .

Vase paintings even had an impact on the development of modern painting. The linear style influenced artists such as Edward Burne-Jones , Gustave Moreau and Gustav Klimt . Ferdinand Georg Waldmüller painted a picture around 1840 with the title Still life with silver vessels and a red-figure bell crater . Even Henri Matisse created a similar picture ( Intérieur au vase étrusque ). The aesthetic influence extends to the present day. The well-known curved shape of the Coca-Cola bottle is also influenced by Greek vase painting.

Scientific research into vases began particularly in the 19th century. Since that time it has also been assumed that the vases are not of Etruscan but of Greek origin. A discovery of a Panathenaic price amphora in Athens by Edward Dodwell in 1819 supported this assumption. The first to provide evidence was Gustav Kramer in his work Styl and Origin of the Painted Greek Clay Vessels (1837). However, it took a few years before this realization could really take hold. Eduard Gerhard published the essay Rapporto Volcente in the Annali dell'Instituto di Corrispondenza Archeologica , in which he was the first researcher to devote himself to the systematic research of vases. To this end, he examined the vases found in Tarquinia in 1830 and compared them, for example, with vases found in Attica or Aegina . During his studies, Gerhard was able to distinguish 31 painter and potter signatures. Until then, only the potter Taleides was known .

The next step in the research was the scientific cataloging of the large museum vase collections. In 1854 Otto Jahn published the vases of the Munich Collection of Antiquities , catalogs of the Vatican Museums (1842) and the British Museum (1851) had already been published. The description of the vase collection in the antiquarium of the Antikensammlung Berlin, which Adolf Furtwängler obtained in 1885, was particularly influential . Furtwängler arranged the vessels for the first time according to artistic landscapes, technique, style, shapes and painting style and thus had a lasting influence on further research into Greek vases. Paul Hartwig tried in 1893 in the book Meisterschalen to differentiate between different painters on the basis of favorite inscriptions, signatures and style analyzes. Ernst Langlotz made a special contribution to dating with his work On the Time Determination of Strict Red-Figure Painting and Simultaneous Sculpture , published in 1920 . Here he introduced dating forms that have been used to this day according to stylistic peculiarities, datable monuments and found complexes as well as Kalos names. Edmond Pottier , curator at the Louvre, initiated the Corpus Vasorum Antiquorum in 1919 . All major collections worldwide are published in this series. To date, more than 300 volumes in the series have been published.

John D. Beazley has made a particular contribution to the scientific research of Attic vase painting . From around 1910 he began to work with vases, using the method developed by the art historian Giovanni Morelli for examining paintings and refined by Bernard Berensons . He assumed that every painter creates individual works of art that can always be assigned unmistakably. Certain details, such as faces, fingers, arms, legs, knees, folds in clothes and the like were used. Beazley examined 65,000 vases and fragments, 20,000 of which were black-figure. In the course of his almost six decades of studies , he was able to assign 17,000 painters to known names or to painters who had been identified using a system of emergency names ; he grouped them into painter groups or workshops, circles and style relationships. He distinguished more than 1500 potters and painters. No other archaeologist has ever had such a formative influence on the exploration of an archaeological sub-area as Beazley, whose analyzes are still largely valid today. In 1925 and 1942 he published his results on red-figure painting for the first time. But his research ended here before the 4th century BC. He did not devote himself to this century until the revision of his work, which was published in 1963. For example, parts of the research results of Karl Schefold , who had made a contribution to researching the Kerch vases, also flowed into this. According to Beazley and in the tradition he established, researchers such as John Boardman or Erika Simon and Dietrich von Bothmer dealt with the red-figure Attic vases. In the recent past, however, the methodological foundations of this form of style analysis and the assignments based on it have repeatedly been criticized as circular .

Arthur Dale Trendall achieved a similarly high status for research into Lower Italian vase painting as Beazley achieved for Attic painting . All the scientists who followed Beazley follow his tradition and use the methods he introduced. Research into vase painting is making steady progress solely because of the new finds that keep coming to light from archaeological excavations, robbery excavations or from unknown private collections.

literature

- John D. Beazley : Attic red-figure vase-painters. 3 volumes. 2nd edition. Clarendon Press, Oxford 1963.

- John Boardman : Red-Figure Vases from Athens. A manual. The archaic time (= cultural history of the ancient world . Vol. 4). von Zabern, Mainz 1981, ISBN 3-8053-0234-7 (4th edition, ibid 1994).

- John Boardman: Red-Figure Vases from Athens. A manual. The classical time (= cultural history of the ancient world. Vol. 48). von Zabern, Mainz 1991, ISBN 3-8053-1262-8 . (2nd edition, ibid. 1996)

- Friederike Fless : Red-figure ceramic as a commodity. Acquisition and use of Attic vases in the Mediterranean and Pontic regions during the 4th century. v. Chr. (= International Archeology. Vol. 71). Leidorf, Rahden 2002 (International Archeology, Vol. 71) ISBN 3-89646-343-8 (Cologne, University, habilitation paper, 1999).

- Luca Giuliani : tragedy, sadness and consolation. Picture vases for an Apulian funeral. National Museums in Berlin - Prussian Cultural Heritage Berlin 1995, ISBN 3-88609-325-9 .

- Rolf Hurschmann : Apulian vases. In: The New Pauly (DNP). Volume 1, Metzler, Stuttgart 1996, ISBN 3-476-01471-1 , column 922 f.

- Rolf Hurschmann: Campanian vase painting. In: The New Pauly (DNP). Volume 6, Metzler, Stuttgart 1999, ISBN 3-476-01476-2 , column 227 f.

- Rolf Hurschmann: Lucanian vases. In: The New Pauly (DNP). Volume 7, Metzler, Stuttgart 1999, ISBN 3-476-01477-0 , Sp. 491.

- Rolf Hurschmann: Paestan vases. In: The New Pauly (DNP). Volume 9, Metzler, Stuttgart 2000, ISBN 3-476-01479-7 , column 142 f.

- Rolf Hurschmann: Sicilian vases. In: The New Pauly (DNP). Volume 11, Metzler, Stuttgart 2001, ISBN 3-476-01481-9 , Sp. 606.

- Rolf Hurschmann: Lower Italian vase painting. In: The New Pauly (DNP). Volume 12/1, Metzler, Stuttgart 2002, ISBN 3-476-01482-7 , Sp. 1009-1011.

- Thomas Mannack : Greek vase painting. An introduction. Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, Darmstadt 2002, ISBN 3-8062-1743-2 (also: Theiss, Stuttgart 2002 ISBN 3-8062-1743-2 ).

- Sabine Naumer: Vases / vase painting. In: The New Pauly (DNP). Volume 15/3, Metzler, Stuttgart 2003, ISBN 3-476-01489-4 , Sp. 946-958.

- John H. Oakley : Red Figure Vase Painting. In: The New Pauly (DNP). Volume 10, Metzler, Stuttgart 2001, ISBN 3-476-01480-0 , Sp. 1141-1143.

- Christoph Reusser : Vases for Etruria: Distribution and functions of Attic ceramics in Etruria of the 6th and 5th centuries before Christ . Zurich 2002. ISBN 3-9050-8317-5

- Ingeborg Scheibler : Greek pottery art. Manufacture, trade and use of antique clay pots. 2nd, revised and expanded edition. Beck, Munich 1995, ISBN 3-406-39307-1 .

- Ingeborg Scheibler: vase painter. In: The New Pauly (DNP). Volume 12/1, Metzler, Stuttgart 2002, ISBN 3-476-01482-7 , column 1147 f.

- Erika Simon : The Greek vases. Recordings by Max Hirmer and Albert Hirmer. 2nd, revised edition. Hirmer, Munich 1981, ISBN 3-7774-3310-1 .

- Arthur Dale Trendall : red-figure vases from southern Italy and Sicily. A manual (= cultural history of the ancient world. Vol. 47). von Zabern, Mainz 1991, ISBN 3-8053-1111-7 .

Web links

Remarks

- ↑ Other theories about the use of a hollow needle filled with paint are rather unlikely; compare John Boardman: Red Figure Vase Painting. The archaic time. 1981, p. 15.

- ^ John Boardman: Red Figure Vase Painting. The archaic time. 1981, pp. 13-15; John H. Oakley: Red Figure Vase Painting. In: DNP. Vol. 10. 2001, Col. 1141.

- ^ John Boardman: Red Figure Vase Painting. The archaic time. 1981, pp. 15-17.

- ↑ a b John H. Oakley: Red Figure Vase Painting. In: DNP. Vol. 10, 2001, Col. 1141.

- ↑ a b c d e John H. Oakley: Red Figure Vase Painting. In: DNP. Vol. 10. 2001, Col. 1142.

- ↑ a b John H. Oakley: Red Figure Vase Painting. In: DNP. Vol. 10, 2001, Col. 1143.

- ↑ The Jena painter. A pottery workshop in classical Athens. Fragments of Attic drinking bowls from the collection of antique cabarets at the Friedrich Schiller University of Jena. Reichert, Wiesbaden 1996, ISBN 3-88226-864-6 , p. 3.

- ↑ Numbers in the cases of the inscriptions refer to the complete Attic-figured vase painting.

- ↑ The first known potter's signature from Attica is that of Sophilos .

- ↑ On the change in the reputation of the craftsmen see Thomas Morawetz: The epitome of bourgeois incompetence. The banause - a search for clues. In: Back then . Vol. 38, No. 10, 2006, pp. 60-65.

- ↑ a b Ingeborg Scheibler: Vase painter. In: DNP. Vol. 12/1, 2002, Col. 1147 f.

- ^ John Boardman: Red Figure Vase Painting. The classic time. 1991, p. 253.

- ↑ Ingeborg Scheibler: Vase painter. In: DNP. Vol. 12/1, 2002, Col. 1148.

- ^ John Boardman: Black-Figure Vases from Athens. A handbook (= cultural history of the ancient world. Vol. 1). 4th edition. von Zabern, Mainz am Rhein 1994, ISBN 3-8053-0233-9 , p. 13; Martine Denoyelle : Euphronios. Vase painters and potters. Pedagogical Service - State Museums of Prussian Cultural Heritage, Berlin 1991, ISBN 3-88609-235-6 , p. 17.

- ↑ See also Alfred Schäfer : Entertainment at the Greek Symposium. Performances, games and competitions from Homeric to late classical times. von Zabern, Mainz 1997, ISBN 3-8053-2336-0 .

- ^ John Boardman: Red Figure Vase Painting. The classic time. 1991, p. 254 f.

- ^ John Boardman: Black-Figure Vases from Athens. A handbook (= cultural history of the ancient world. Vol. 1). 4th edition. von Zabern, Mainz am Rhein 1994, ISBN 3-8053-0233-9 , p. 13.

- ↑ a b Thomas Mannack: Greek vase painting. 2002, p. 36.

- ^ John Boardman: Red-Figure Vases from Athens. The classic time. 1991, pp. 198-203.

- ^ Rolf Hurschmann: Lower Italian vase painting. In: DNP. Vol. 12/1, 2002, Col. 1009-1011.

- ^ Rolf Hurschmann: Lower Italian vase painting. In: DNP. Vol. 12/1, 2002, Col. 1010 and Arthur Dale Trendall: Red-figure vases from southern Italy and Sicily. 1991, p. 9, with slightly different information. The more recent Hurschmann names with 21,000 vases 1000 more than Trendall, which also accounts for the numerical difference between the statements of both authors for the Apulian vases. Hurschmann only gives the general number, plus the number of Apulian and Campanian vases, Trendall gives an even more detailed breakdown.

- ↑ Rolf Hurschmann: Apulian vases. In: DNP. Vol. 1, 1996, Col. 922 f.

- ↑ a b Rolf Hurschmann: Apulian vases. In: DNP. Vol. 1, 1996, Col. 923.

- ^ Rolf Hurschmann: Campanian vase painting. In: DNP. Vol. 6, 1998, Col. 227.

- ^ Rolf Hurschmann: Campanian vase painting. In: DNP. Vol. 6, 1998, Col. 227 f.

- ↑ a b Rolf Hurschmann: Campanian vase painting. In: DNP. Vol. 6, 1998, Col. 228.

- ↑ Rolf Hurschmann: Lucanian vases. In: DNP. Vol. 7, 1999, Col. 491.

- ↑ Rolf Hurschmann: Paestanische vases. In: DNP. Vol. 9, 2000, Col. 142.

- ↑ Rolf Hurschmann: Paestanische vases. In: DNP. Vol. 9, 2000, Col. 142 f.

- ↑ a b Rolf Hurschmann: Sicilian vases. In: DNP. Vol. 11, 2001, Col. 606.

- ↑ Thomas Mannack: Greek vase painting. 2002, p. 158 f.

- ↑ Thomas Mannack: Greek vase painting. 2002, p. 159 f.

- ^ Reinhard Lullies in: Antique works of art from the Ludwig collection. Volume 1: Ernst Berger, Reinhard Lullies (ed.): Early clay sarcophagi and vases. Catalog and individual representations (= publications of the Antikenmuseum Basel. Vol. 4, 1). von Zabern, Mainz 1979, ISBN 3-8053-0439-0 , pp. 178-181.

- ↑ Huberta Heres , Max Kunze (ed.): The world of the Etruscans. Archaeological monuments from museums of the socialist countries. Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, capital of the GDR, Altes Museum, from October 4 to December 30, 1988. Henschel, Berlin 1988, ISBN 3-362-00276-5 , pp. 245–249 (exhibition catalog).

- ↑ Huberta Heres, Max Kunze (ed.): The world of the Etruscans. Archaeological monuments from museums of the socialist countries. State museums in Berlin, capital of the GDR, Altes Museum, from October 4 to December 30, 1988. Henschel, Berlin 1988, ISBN 3-362-00276-5 , pp. 249–263 (exhibition catalog).

- ↑ Balbina Bäbler speaks in DNP. Vol. 15/3 ( calendar: I. Classical Archeology. Sp. 1164) of 65,000 vases that Beazley examined. From this 20,000 are to be subtracted, which according to Boardman were black-figure (John Boardman: Black-figure vases from Athens. A handbook (= cultural history of the ancient world. Vol. 1). 4th edition. Von Zabern, Mainz am Rhein 1994, ISBN 3-8053- 0233-9 , p. 7). As already explained, 21,000 red-figure figures come from southern Italy. There are also other pieces from other places in Greece

- ^ Sabine Naumer: Vases / vase painting. In: DNP. Vol. 15/3, Col. 946.

- ^ Sabine Naumer: Vases / vase painting. In: DNP. Vol. 15/3, Col. 947-949.

- ^ Sabine Naumer: Vases / vase painting. In: DNP. Vol. 15/3, Col. 949-950.

- ^ Sabine Naumer: Vases / vase painting. In: DNP. Vol. 15/3, Col. 951-954.

- ^ Sabine Naumer: Vases / vase painting. In: DNP. Vol. 15/3, Col. 954.

- ↑ Thomas Mannack: Greek vase painting. 2002, p. 17.

- ↑ Thomas Mannack: Greek vase painting. 2002, p. 18.

- ^ John Boardman: Black-Figure Vases from Athens. A handbook (= cultural history of the ancient world. Vol. 1). 4th edition. von Zabern, Mainz am Rhein 1994, ISBN 3-8053-0233-9 , p. 7 f .; Thomas Mannack: Greek vase painting. 2002, p. 18 f.

- ↑ James Whitley: Beazley as theorist. In: Antiquity. Vol. 71, H. 271, 1997, ISSN 0003-598X , pp. 40-47; Richard T. Neer: Beazley and the Language of Connoisseurship. In: Hephaestus. Vol. 15, 1997, ISSN 0174-2086 , pp. 7-30.