Lentia (Noricum)

| Lentia Castle | |

|---|---|

| Alternative name |

a) Lentio , b) Lentia |

| limes | Limes Noricus |

| section | Route 1 |

| Dating (occupancy) | Tiberian-Claudian, 1st to 5th century AD |

| Type | Alenkastell |

| unit |

a) Ala I Thracum Victrix , b) Numerus? c) Ala I Pannoniorum Tampiana victrix , d) Cohors II Batavorum ? , e) Legio II Italica , f) Eequites sagittari |

| size |

a) 0.67 ha (early wood and earth fort), b) 3 ha (stone fort I) |

| Construction | Wood, earth and stone construction |

| State of preservation | No building remains are visible from the fort. |

| place | Linz |

| Geographical location | 48 ° 18 '11 " N , 14 ° 17' 26" E |

| Previous | Watchtower Hirschleitengraben (west) |

| Subsequently | Lauriacum (east) |

Fort Lentia was part of the Roman fort chain on the Danube Limes in the Roman province of Noricum in what is now the Austrian state of Upper Austria , in the area of the provincial capital Linz .

For a long time, the fortification was considered to be the oldest documented fort in Noricum. The cavalry camp, which is archaeologically proven only in small sections in the old town and on the Römerberg (late antique or early medieval stone fort II), was built in the late 1st century AD and was probably occupied by Roman soldiers until the middle of the 5th century.

It served to secure the strategically important crossing point of a trade route that led from the south across the Danube to the north, with the Limes road running from west to east, the via iuxta Danuvium , which connected the Roman military bases and settlements on the banks of the Danube and their hinterland .

Lentia was devastated several times by Germanic incursions, but as an oppidum it survived the upheavals during the migration of peoples and was continuously settled during the early Middle Ages. The grave goods from the 1st to 5th centuries AD testify to the modest prosperity of its residents.

Location, topography and road connections

The Danube flows through the Linz Basin in a large bend to the south, which is bounded in the west by the Schlossberg, Römerberg, Freinberg, Bauernberg, Gaumberg, in the north by the Mühlviertel hill country (Pöstlingberg, Gisela Warte) and in the east by the Pfenningberg. The lower terrace of the Linz basin consists of alluvial gravel covers. Even older gravel deposits occur mainly on the eastern slope of the Linz Schlossberg. Sedimentary alluvial land near the so-called Linzer Enge in the west (on the Freinberg) indicates that the river was originally wider. There were also passable fords in several places. Two important traffic routes, used since prehistoric times, led through the Haselgraben and Katzbach and were the shortest connection to the Vltava valley .

Antique pavement finds in Herrenstrasse and Stockhofstrasse, graves and small finds in Scharlinz and Kleinmünchen suggest that a Roman road from north to south once passed here. Another north-south connection appears to be secured by graves along the mountains bordering Linz to the west of the vicus. Another road leading to the west, which runs along the railway line at Untergaumberg and parallel to the so-called Ochsenstraße in the direction of Pasching, has also been proven by road findings and rows of ancient graves.

Surname

The place name " Lentia " is only mentioned in the Notitia Dignitatum . At first, experts were of the opinion that it was derived from a Celtic proper name - either from Lentios or Lentius , linden (lindö) or landing place (lend / lent) . According to the majority of linguistic interpretations, the fort name probably comes from the Celtic name for "curved", lentos . The Celts preferred to formulate their place names according to special topographical features in the surrounding landscape. The course of the Danube , which still has a distinctive bend near Linz today, therefore seems - with great probability - to have given the fort its name.

function

The region around Linz has been particularly exposed since the Marcomann Wars. Opposite the Danube bend is the Haselgraben and a second valley cut at the Pfennigberg; these were ideal as approach routes and assembly points for attacks on the Danube border . There are also several floodplains in the vicinity, which also facilitated a transition to the southern bank of the Danube. The northern bank of the Danube was also very flat, which made it easier for hostile barbarian tribes to occupy it. In addition, the Danube crossed here with a salt trade route (from the mouth of the Traun over the Pyhrn Pass to the south) and the long-distance connections leading through the Linz Forest and the Gallneukirchen Basin to the South Bohemian Gate. Observing these endangerment points and keeping them under control or securing them should have been the main task of the fort crew.

Dating

The founding date of the fort is controversial in research. The evaluation of the finds (ceramics, terra sigillata , militaria, double pointed trenches) led Paul Karnitsch in 1954 to the opinion that the Alenkastell could have been founded in the reign of Vespasian around 46 AD. After the excavations at the State Theater in 1955, however, it is clear that a smaller military base must have existed here since Augustan or Tiberian times. The wood and earth fort was probably demolished between 140 and 160 AD and replaced by a stone fort (SK I). This was probably burned down again in the Marcomann Wars. Large-scale destruction could also be proven during the reign of Aurelian . The last verifiable repair and renovation work (SK II) was carried out in the time of Emperor Valentinian I (364–375). In the second half of the 5th century, the fort was abandoned by the Roman army.

Research history

The dense development of the inner city from the Middle Ages to modern times made archaeological investigations in this area very difficult. For the most part, one was dependent on emergency excavations. Scheduled exposures could only be carried out from the 1980s. The archaeological-topographical investigations were limited to the height of the Freinberg, Martinsfeld, Schlossberg and the area between the promenade and Spittelwiese.

Scientific studies have been carried out in the old town of Linz since the middle of the 19th century. The clergyman ( Augustinian canon ) Joseph Gaisberger is considered to be the founder of systematic provincial research in Upper Austria, the main aim of which was originally the localization of the Roman Lentia . Initially, however, most of the knowledge about this was based on chance finds during canal excavations and construction work. In 1841 Gaisberger's first report on Roman antiquity in Linz appeared, which today can be regarded as the basis of the topography of ancient Lentia . Gaisberger also tried to roughly sketch its extent based on the sites, which in his opinion included the following squares and streets:

- Spittelwiese,

- Steingasse,

- Klammstrasse,

- Theatergasse,

- the area from the old town to the city scales,

- the former imperial castle,

- the Plank garden as well

- the main square.

At the foot of the Römerberg, finds from the early 1st century and post holes were later discovered during the "fort excavations". The first attempts to systematize and scientifically evaluate previous research and excavation activities were made in 1927 by Paul Karnitsch, which culminated in his first independent and extensive excavation projects in Linz's old town at the end of the 1920s. The uncovering of Roman urn graves on the property of the Sisters of the Cross in the 1920s represented a major step forward. The 140 graves examined are still considered to be important source material due to their closed nature. Several of the cremation graves contained - in addition to the usual ceramic vessels - mainly glass and jewelry from northern Italian workshops, statuettes from Gaul and finely crafted bronze vessels, which not only suggest extensive trade relations, but also a certain wealth of some Lentiens. The local researcher Ferdinand Wiesinger (1864–1943) was also able to provide initial information about the living conditions of the Roman settlers of Linz with found objects known as terra sigillata . He created a chronological framework of the ancient settlement of Lentia and also a topography of the Roman settlement, which he also assumed to be in the old town of Linz and in the zones adjacent to it.

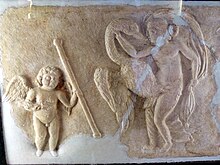

After the Second World War, the remains of a "Holy District" and a " Gallo-Roman temple " were excavated in Hahnengasse and Tummelplatz . While the findings of the latter were doubted by later research, the identification of the second building as a mithraium was confirmed . The remains of a Roman-era house (initially incorrectly interpreted as " Burgus ") and Roman objects recovered from it contributed significantly to the completion of the findings known up to that point. In the course of an urgently needed restoration, the Martinskirche on the Römerberg was the scene of extensive investigations in 1948/1949. Reliefs from Roman times and a furnace filled with ceramic shards came to light (late La Tene period ceramics and Arretium ware). During the excavations in the Martinskirche and on Martinsfeld, an even earlier Roman period discovery horizon emerged. a. multi-phase strip houses . From 1976 the Martinskirche and Martinsfeld moved again into the center of archaeological activities. Precise layer observations made it possible to gain new knowledge about certain aspects of prehistoric, Roman and early medieval Linz. 1977–1979 a massive surrounding wall and walls of buildings of the late antique settlement area were observed at Martinsfeld and new findings were found.

In 2000, a defensive moat from the late antiquity to the west of the Linz City Palace was examined; finds of militaria and brick stamps also suggested a military presence, as can be seen from the additions and costume components in the late Roman burial ground at Tiefer Graben / Flügelhofgasse. The excavations on the promenade in the years 2005 to 2008 brought to light again layers of settlement, a building with a colonnade and the waste pit of an ancient butcher shop. In 2007, a metalworking workshop was also found on the Upper Donaulände.

development

From 400 BC Chr. Began Celts in the surrounding area of Linz immigrate. 200 BC They founded their first permanent state - the Kingdom of Noricum (regnum Noricum) . On the Freinberg they built a larger ring wall system, on the Martinsfeld a settlement was built, both existed until the late 1st century AD. On the Gründberg , in today's Urfahr , there was also a 500 m long Celtic wall system at the same time ( Oppidum von Gründberg ).

Around 15 BC BC the Romans occupied Noricum and built their first military base in Lentia around 50 years later in order to control the trade routes converging here. Shortly after the fort was built, the civilian settlement ( Canabae or Vicus ) must have been built on the Hofberg. Around 19 AD, the Marcomanni ruler Marbod near Lentia, who had been deposed in his homeland, moved to Roman territory and from here went into exile in Rome. Under Hadrian (117-138) or later ( Antoninus Pius ) (138-161), the wood-stone camp was converted into a larger stone fort (Stone Fort I). Around 270 AD, Lentia was almost completely devastated by the Marcomanni, but was quickly rebuilt afterwards. In the late 3rd century further extensive destruction followed. In the 4th century, the stone fort I was abandoned under Valentinian I and instead a new fortification was built on the nearby Römerberg, which also included the civil settlement.

In the biography ( vita ) of Severin von Noricum , a main source for the final phase of Roman rule in Ufernoricum ( Noricum ripense ), Lentia is not mentioned. From 488 also the last remnants of the Roman army and administration dissolve in Noricum, much of the novels was on the orders of Odovacar evacuated to Italy mainly in order to in Krems based Rugiern harming economically. From 511 the Lombards occupied the areas on the Noric Danube, later followed by the Avars and Slavs , until the large migrations finally came to an end in the colonization by the Bavarians .

In 791 Charlemagne also passed Linz with his army on the occasion of a campaign against the Avars . In 799, the emperor transferred the Martinskirche and the associated castrum to his brother-in-law Gerold as a fiefdom, with " Linze " being mentioned for the first time.

Fort

The presence of Roman soldiers in Linz is considered to have been proven, but opinions differed over the course of the history of research regarding the location of the fort. The exact location and extent of the multi-phase fastening has not yet been fully clarified due to the dense construction. Even recent excavations could not prove it beyond doubt at the postulated locations. The findings of the investigations at the Landestheater in the 1950s were viewed by Paul Karnitsch as pointed trenches and gates of a wood-earth fort from the first half of the 1st century; the foundations of stone walls, however, later interpreted by him as the remains of the stone fort that stretched from Lessingstrasse to Klammstrasse. Walter Podzeit and Erwin M. Ruprechtsberger were able to largely refute this assumption. According to the current state of research, especially after the excavations and explorations by Erwin Ruprechtsberger (from 1980) and Christine Ertel (2005), the location of the fort is between

- Promenade and Klammstraße (north flank),

- at the height of the Spittelwiese, d. H. Baumbachstrasse and Bischofstrasse (south flank),

- Waltherstrasse and Herrenstrasse in the west and

- the country road in the east

suspected with its center ( Principia ) north of the academic high school . To the east were the barracks, to the south a warehouse (Horreum) , to the west the commandant's house (Praetorium) , the hospital (Valetudinarium) , the camp bath (thermal bath) and workshops. Judging by the findings, the two wood-earth camps and stone camp I existed from the 1st to the 3rd century AD.

Wood and earth fort

In the case of the early fort (probably the State Theater at the foot of the Römerberg), a total of two construction phases could be distinguished. Although only very few finds could be recovered from construction phase I, Paul Karnitsch tried to reconstruct the extension of the wood and earth fort on the basis of the discovery of a double ditch and a gate system on the north wall. For this, Karnitsch calculated lengths of 78.50 m (N) × 79 m (S) × 79.90 m (W) × 87.60 m (O) and thus a trapezoidal area of 0.67 ha. Only post holes marked the almost square floor plan of the eastern gate tower (4.80 × 3.90 m), the wooden frame of which was apparently boarded with planks on the underside and wickerwork on the top. The passage between the two gate towers was about 3.60 m. The 2.10 to 2.40 m wide fort wall was attached to the tower. In the vicinity of the presumed west gate, the remains of an identical intermediate tower were found. Incidentally, the development of the fort wall was similar to that of Fort Künzing on the Raetian Limes , according to Karnitsch . Phase II, in which the Principia were also established, falls, according to Karnitsch, in the time of Vespasian .

Stone fort I

The Antonine fort probably had the classic playing card shape (according to Karnitsch 285–300 × 190 m) with rounded corners, which also influenced the subsequent development in this district. The area between the streets already mentioned for Steinkastell I is approx. 350 × 260 m, so a total of 9.1 ha. For the fort itself, however, only an area of approx. 3 ha would be assumed. Two pointed trenches (width: 4.50 m, depth: 1.60–2 m), small traces of the northern and southern gate and a pentagonal (!) Tower in the northwest corner (4 × 3 × 260 m). The other corner towers were probably constructed similarly. On the west and east sides a 1.30 to 1.45 m thick wall was uncovered, in places the wall was still over 1 m high. It was reinforced by internally attached, rectangular intermediate towers (6 × 5.70 × 5.30 m), of which a total of five could be identified (Schlossergasse, Hirschgasse and Klammstrasse or the corner of Hirschgasse). In the rear near area of the wall there were remains of a 3 m wide earth ramp - which served as a battlement - and the gravel, 9 m wide wall road (via sagularis) .

Stone fort II

In the 4th century, the stone fort I was abandoned, the occupation of which withdrew to the civilian settlement on the Schlossberg or Römerberg, which turned it into a fortified village ( oppidum ) , a development stage that was often observed on the Danube Limes at this time. Two standard attachments and bronze belt buckles, as well as a wide, north-south-running and four-meter-deep pointed ditch on the Keplerwiese, which was discovered in August 2002 and which was filled with late antique finds (including coins of Emperors Gallienus , Konstans and Valentinian I and Valens), confirm this , Lance tips, belt fittings) the presence of military personnel. It could be followed for another 30 meters before it finally turned sharply west. Another ditch in the northwestern area of the palace terrace was originally 3.5 m deep. The exact positioning of the late antique military complex on the basis of the few available findings is difficult; it was probably located near the Martinskirche. There is also a height difference of almost ten meters between the so-called “fort ditch” and another ditch east of the Martinskirche, which makes a functional connection between these two ditch sections appear problematic. In addition, the question arises why the moat on the castle terrace was leveled again in late antiquity.

Interior constructions

From the interior, only the remains of the Principia , north of the Academic Gymnasium, and a room in a building with a colonnade at the theater casino were observed. In 1927, Roman masonry (buildings A and B) was uncovered in the courtyard of Promenade No. 23 (Wimmer printing works). The Roman cultural layer observed was about 1.20 m deep and was 8 to 40 cm thick.

Building a

An apse in the northern area of the inner courtyard probably belonged to a building that continued to the north, which was destroyed in 1878 when the Wimmer printing works were built. The 60 to 70 cm thick wall consisted of mortared rubble and was still 20 cm high. Its western exterior could be traced to a depth of 1.95 m; the foundations widened to 1.20 m. In the south, the outer walls were preserved up to a height of one meter and the foundations spread up to 0.9 m. The floor was paved with four layers of mortar roof tiles (tegulae) and a terrazzo floor three centimeters thick. The total floor thickness was 28 cm. There was a 5 to 15 cm thick culture layer on top from which a lance tip could be recovered.

Between object A and rooms B to the south, three gravel areas of 8 to 15 cm thickness were exposed at a depth of 1.25 to 1.3 m; It could not be clarified whether this was a road running WO.

Building B

This was a multi-phase, square building with several rooms. The foundation walls sat on layers of gravel. Furthermore, a hypocaust and wall heating as well as a subsequently added praefurnium could be observed. A brick stamp of an ala was discovered in the largest room, which is 15.40 mx 7.70 m. Fragments of a wall painting were also found here. A well built in dry stone with a mortar edging probably also dates from Roman times.

garrison

The traces of the unusually wide streets in the interior of the fort led Paul Karnitsch to conclude from the start that the crew were cavalry. Bricks with the imprint ALTP could be related to the two cavalry units presumed here, and inscriptions also provide information about the identity of the troops stationed in the fort. After the discovery of a - albeit difficult to read - brick stamp with the imprint leg X or XV , Karnitsch did not consider the brief presence of a vexillation of the Legio XV Apollinaris stationed in Carnuntum or the Legio X Gemina from the year 63 AD to be entirely locked out.

| Time position | Troop name | comment | |

| early 2nd century AD | Ala prima Thracum victrix (the first squadron of Thracians , the victorious) | When this unit was set up is unknown. On the Stein 4 military diploma , she is given her honorary name victrix for the year 95 AD in the Norican troop list. Presumably she replaced the ala prima Hispanorum ("first Hispanic cavalry squadron ") in Noricum. Military diplomas prove her stay on the Danube from 126 AD, but only for the neighboring Upper Pannonia. At the beginning of the 2nd century the cavalry troops were assigned to the Dacian War of Trajan . An inscription recovered in 1953 in the temple precinct suggests that this unit could have been an occupation of the early wood and earth fort around 122 AD. | |

| Mid 2nd century AD | unknown number (unit / group) | A numerus could also be considered as the crew , as several Tegula bricks with the stamp NVMER (V) S in abbreviated and ligated versions could be recovered in Linz (Spittelwiese). The bricks were mainly found in the civil settlement, they are likely from the 2nd century. The specimens with the NVMER imprint were made on site, the bricks with the NVM B stamp, however, must have been delivered. Possibly they come from the brickworks of the numerus Boiodurensium in Passau, which at that time supplied several other places on the Noric Danube. | |

| 2nd to early 3rd century AD | Ala prima Pannoniorum Tampiana milliaria victrix (the first Pannonian cavalry squadron of Tampius, 1000 strong, the victorious) | This unit was probably recruited from members of the Pannonian tribes under Augustus. The name "Tampiana" is probably originally derived from one of its commanders. The riders were in Britain in the 1st century and were relocated to the Danube Limes between 85 and 86 AD, where they took part in the border wars of the emperors Domitian and Nerva . The unit stayed briefly in Carnuntum . In 97 AD it returned to Britain - replenished with Pannonian personnel. Since then it has been nicknamed Pannoniorum . In the 2nd century AD she was set on the march again towards the Danube border, moved into the camp in Lentia and probably replaced the ala I Thracum victrix as the occupation force. According to the troop list of the military diploma discovered in Mautern , she probably returned to Noricum between 127 and 138 AD. Presumably it was used for Mark Aurel's campaigns in the east at this time . There she acquired her honorary name victrix and was increased to 1000 men (milliaria) . So far, two military diplomas are known in which the unit appears.

The troops are indicated for Lentia on the inscription of a consecration altar, which dates from the turn of the 2nd / 3rd century. Century is dated. The altar was a dedication by Castricius Sabinus to the genius of the commander of his unit, Gaius Domitius Montanus Septimius Annius Romanus. The assignment of a brick stamp found in Linz to this troop is unclear. Otherwise two altar inscriptions and a tombstone are known from Noricum for this troop. |

|

| unknown | Cohors secunda Batavorum civium Romanorum (the second Batavian cohort of Roman citizens) | This auxiliary group, which in Austria has so far only been documented as the occupation of Klosterneuburg Castle , is only known to Lentia from a fragment of an inscription in St. Martin's Church. It was probably commissioned by one of their veterans who might have retired here. Whether his former unit was also stationed here is still controversial in research circles. | |

| early 4th to mid 5th century AD |

Legio secunda Italica et equites sagittarii , (the second legion of Italians and mounted archers) |

Brick stamps of the Legio II Italica indicate the construction departments of this legion, which was originally stationed in Enns / Lauriacum . Major changes in the number of crews and the location of the Legion began at the end of the 3rd century. Under Diocletian it was reduced to 2,000 men and distributed over several forts ( Lauriacum , Iovacum and Lentia ). A new legion, the legio I Noricorum, was set up for Noricum . The latter was from now on responsible for the protection of today's Lower Austrian, the legio II Italica for the Upper Austrian section of the Noric Danube.

In the Notitia Dignitatum in the troop list of the Dux Pannoniae Primae et Norici Ripensis, a praefectus legionis secundae Italicae partis inferioris (= lower section), Lentiae as the commander of a vexillation of the second italica and mounted archers are mentioned. These were cavalrymen who were trained to use bows and arrows as well as to fight with swords and lances. |

Vicus

The center of the civil settlement was at the foot of the Schlossberg between the State Theater and Tiefer Graben. The legal status of the vicus of Lentia has remained unknown to date. An inscription walled up in Martinskirche names a quaestor , but the incompletely preserved inscription stone was probably brought to Linz from another Roman city or settlement. The fort vicus was evidenced by extensive wall remains from residential and farm buildings (foundations, hypocausts and a cellar). The 1st century settlement covered parts of today's Martinsfeld and the south-sloping slopes of the Römerberg up to the western part of Linz's old town. This area had mostly stone buildings dating from the Middle Imperial Age. Architectural parts, such as fragments of columns, are likely to be remnants of arcades and porticos . The vicus reached its greatest extent in the Middle Imperial period, at that time it reached close to the fort walls (today the area around the promenade and Spittelwiese). Its northern limit is at the level of Hofgasse, directly on the slope to the Danube bank. The empty space on the northern part of the main square and in Hofgasse suggest that these areas were not built over in antiquity. The fortified late antique settlement, to which the military had finally withdrawn, was on the ridge of the Martinsfeld and on the Schlossberg and Römerberg. It was surrounded by a massive wall, the remainder of which could be observed west of the Martinskirche.

On the vicus buildings, several construction phases can usually be recognized. While the first dwellings were still simple wooden huts (foundation ditches and post holes in wooden post structures on the Martinskirche, Promenade and Spittelwiese), the new and more comfortable construction method soon established itself. The Romans introduced brick and stone construction as well as a mixed technique of stone-wood construction. On brick foundations z. B. placed half-timbered structures, the wattle walls were plastered with clay and lime. The furnishings of these houses sometimes also included wall and floor heating in some rooms ( hypocaust ) . Good examples of this are the walls discovered on the Freinberg, Martinsfeld or Martinskirche and Keplerwiese and a cellar of a strip house excavated on the Alter Markt .

economy and trade

The civil settlement continuity can be proven in Linz from the late Latène period to the late imperial period. The heyday of the fort vicus extended into the last third of the 3rd century, from the second half of the 5th century the Roman finds gradually thinned out. At Martinsfeld and Keplerwiese, on the southern slopes of the Römerberg and occasionally in the old town, both ceramics of the late Latène period and Roman imported goods from the early imperial period were found. Melting furnaces in a metalworking trade, baking ovens and waste pits complement these findings. Bone carvings are also proven.

Above all, the finds in and around the early medieval St. Martin's Church suggest that the civilian population was modestly prosperous. An oven and millstones preserved in the church provide evidence of workshops and simple accommodation, which were replaced by stone buildings in the 2nd century.

According to the findings of the excavations in the 1980s, Erwin Ruprechtsberger suspects that a craftsmen's quarter also spread along Lessingstrasse and the slopes of the Römerberg, in which, to a modest extent, u. a. Iron was smelted and bones worked. In summary, the existence of an extensive and prosperous settlement can be assumed for the 1st to 3rd century, whose trade connections reached as far as Italy, as could be seen from imported goods of terra sigillata and amphorae as well as from the spectrum of coins.

Burial grounds

A mid-imperial cremation grave field (1st to 2nd century AD) was located on the southern arterial road of the fort, on the area of today's Kreuzschwesternschule. It was examined in 1926/27, and over 140 cremation burials and a few body graves from the 3rd century AD were uncovered. What was surprising was the discovery of some graves with very rich gifts. Two glass bottles made in Aquileia again indicated the far-reaching trade relations of the residents of Lentia . It is probably the burial ground of the early canabae and the fort.

Another burial ground dates from the last third of the 4th century and was occupied until the 530s. It is located about 150 meters from Martinskirche (Tiefer Graben and Flügelhofgasse) and gave scientists a good insight into the funeral rites of late antiquity. Five of a total of 37 of the dead buried here had belts with fittings that served as a badge of rank for members of the late Roman army in higher positions. They have never appeared in this density in any other known Roman burial ground. Possibly these are burials of higher army members in late antique Lentia . Another late antique (4th to early 5th century), considerably smaller burial ground was on the Römerberg. These were graves of a socially graded population who settled on the Schlossberg until the middle of the 5th century. The burials between Tiefen Graben and Schlüsselhofgasse were particularly informative for the anthropologists, as pathological findings could be made on the basis of the bones (polio, bone cancer), which enabled conclusions to be drawn about the living conditions of the residents of that time.

Temple precinct

In the Martinskirche the inscription of a certain Aurelius Eutices (Eutyches) was discovered, who as sexvir Augustalis , d. H. acted as a priest of the official imperial cult, but Eutices is more likely to have exercised his office in the city of Ovilava (Wels) than in Lentia. A Mithra temple in the camp village of Lentia, uncovered by Paul Karnitsch in 1951, deserves special mention . Adjacent to this there was also a temple of Jupiter Dolichenus . The findings of the Mithraum confirm the unusually long lifespan of this cult on the Danube Limes of the late period for the Roman Empire at that time, as the old religions were massively oppressed by Christianity and had only a few followers.

The four proven, multi-phase cult buildings (based on Karnitsch 1956)

- T I-IV, mithraea,

- TV, temple of the two gods,

- T VI, Temple of the Capitoline Triassic (Jupiter Dolichenus),

- T IX, Temple of Epona ,

surrounded a small forum. The oldest buildings (remains of walls, wells) can be traced back to the end of the 1st century, 184 AD (coin finds). As a result, two building complexes to the north and south were identified, which were connected to one another by a corridor added later. In the south there was a brick pedestal, on which a wooden cult statue probably once stood. A coin of Claudius II Gothicus was also found in the rubble . To the north, an 8.4 × 12.9 m square wall was recognized, in which two square foundation blocks stood, which probably also served as the basis for statues (temple of the two gods). The Mithraeum was in the northeast section of the excavation. Under Constantine I and his successors, major renovations were carried out in the temple area in the middle or end of the 4th century. While the military and civilian population retreated to Schlossberg and Römerberg in the 4th century, the mithraeum in the former vicus area was apparently used until the early 5th century (coin finds, glazed cult vessels with snakes on top).

Mithraeum

In 1951, at Tummelplatz 3–4, the edge zone of a Roman-era, tile-roofed building with screed floors and a cistern was cut. A total of four construction phases could be distinguished from each other in the building. Period I came from the time of the Marcomannic Wars (probably AD 171), the previous building had burned down at this time and was not rebuilt. The remaining part belonged to Periods II and III, which were to be dated to the 3rd century AD. Only a few remains of phase IV (late antiquity) were left. Furthermore, it was found that the walls were once painted in the colors red and yellow. In the opinion of the excavator, the building was a small, four-room mithraium that was built between 275 and 276 AD and fell victim to a fire in the late 4th or early 5th century.

In the building itself - in addition to a large amount of oyster shells, fruit pits and leftover eggs, three vessels with green glazed handles with snakes wound around them, coins from Emperor Tacitus (275–276 AD) to Honorius (383– ) were found. 423 AD) and a 30 × 30 cm large stone block with a remnant of an inscription (I THRAC V) of I Thracum victrix . The fragments of two marble Mithras reliefs were discovered next to a pillar on the east wall. The genius altar of the prefect of the ala I Pannoniorum Tampiana victrix was found on the north wall as a spoil . The inscription of another walled-in votive stone was dedicated to the god Mithras by a veteran. In the adjoining room to the south, an oblation plate with inscriptions for Jupiter and Mithras as well as silver votive sheets, which were intended for the Jupiter-Dolichenus cult, was found.

Temple of the Two Gods

At Tummelplatz 4, Karnitsch was able to examine another 8.40 m × 12.90 m × 7.20 m × 11.55 m building. Inside there were square wall foundations, which probably once supported two statues of gods, of which, however, no traces could be found. The building dates from the 3rd century and was used until the 4th century.

Gallo-Roman common temple

When the house at Hahnengasse 3 was demolished, a Roman road was found on the northern property boundary and could still be traced to a length of 8.8 m. On it lay charred remains of beams that came from the buildings adjoining to the south. As a result, remains of Roman walls were also found, which lay in a Roman cultural layer and were partially covered with layers of fire. Wall I consisted of rubble stones with a white lime mortar bond; A water basin (IV) came from the same period. Wall II had a yellowish, sandy mortar bond with inserted posts. The parallel walls, which Karnitsch added later, were interpreted by him as a Gallo-Roman temple . Only a two-phase construction is certain, the structure and chronology of which, however, cannot be clearly understood due to the disturbances mentioned. In reality, it was probably an ordinary residential building in the vicus.

Monument protection

The facilities are ground monuments within the meaning of the Monument Protection Act. Investigations and targeted collection of finds without the approval of the Federal Monuments Office are a criminal offense. Accidental finds of archaeological objects (ceramics, metal, bones, etc.) as well as all measures affecting the soil must be reported to the Federal Monuments Office (Department for Ground Monuments).

Note

Linz can be reached by car via the A1 motorway, the B1 federal highway or by train. From the main train station you can take tram lines 1 and 3 directly to the old town (main square). Parking spaces in the city center are rare and payable. It is therefore advisable to visit the sights on foot. You can also easily get to the center or main square via the Danube Cycle Path. Roman spoils with inscriptions are walled up in the interior of the Martinskirche on Römerberg.

See also

literature

- Thomas Fischer : Noricum . Zabern, Mainz 2002, ISBN 3-8053-2829-X ( Orbis Provinciarum , Zabern's illustrated books on archeology , special editions of the ancient world ).

- Kurt Genser : The Austrian Danube Limes in Roman times, a research report. (= The Roman Limes in Austria. 33), Vienna 1986, pp. 99–125.

- Kurt Genser: Lentia-Linz from a military point of view. In: Christine Schwanzar, Gerhard Winkler (ed.): Archeology and Regional Studies, contributions to the conference in the Linz Castle Museum 26. – 28. April 2007, in cooperation with the NORDICO - Museum of the City of Linz . Linz 2007.

- Manfred Kandler, Hermann Vetters (ed.): The Roman Limes in Austria. A leader . Vienna 1989.

- Paul Karnitsch: The Roman buildings on the promenade and in Steingasse. In: Yearbook of the City of Linz 1951. Linz 1952, online (PDF) in the forum OoeGeschichte.at.

- Paul Karnitsch: A Gallo-Roman temple in the old town of Linz. In: Yearbook of the City of Linz 1954. Linz 1955, online (PDF) in the forum OoeGeschichte.at.

- Paul Karnitsch: The Holy District of Lentia. In: City of Linz (Hrsg.): Historisches Jahrbuch der Stadt Linz 1956. Linz 1956, online (PDF) in the forum OoeGeschichte.at.

- Erwin M. Ruprechtsberger : Linz-Lentia, fort and vicus. In: Herwig Friesinger, Fritz Krinzinger (Hrsg.): The Roman Limes in Austria. Guide to the archaeological monuments . Vienna 1997.

- Erwin Maria Ruprechtsberger: The late antique burial ground of Lentia (Linz) - excavation Tiefer Graben / Flügelhofgasse. Bonn 1999 (monographs of the Roman-Germanic Central Museum, Research Institute for Pre- and Early History; Volume 18).

- Erwin Maria Ruprechtsberger: Antique Lentia - new research and knowledge. In: Jutta Leskovar , Christine Schwanzar, Gerhard Winkler (ed.): What we stand on. Archeology in Upper Austria . 2003 (Catalogs of the Upper Austrian State Museum. New series, volume 195).

- Erwin Maria Ruprechtsberger: The excavations in the area of the Spittelwiese as reflected in recent research - an overview. Linz 2005 (Linz Archaeological Research No. 36).

- Erwin Maria Ruprechtsberger: Linz - Lentia. Fort - settlement . In: Verena Gassner / Andreas Pülz (ed.): The Roman Limes in Austria. Guide to the archaeological monuments , publishing house of the Austrian Academy of Sciences, Vienna 2015, ISBN 978-3-7001-7787-6 , pp. 155–162.

- Peter Scherrer : St. Pölten: State capital with Roman roots. Results of urban archeology 1988–1998 . State capital St. Pölten and Austria. Archaeological Inst. (Ed.). Vienna 1998, ISBN 3-900305-26-9 .

- Dorit Schön: Oriental Cults in Roman Austria. Böhlau Verlag, Vienna / Graz / Cologne 1988, ISBN 3-205-05016-9 .

- Hannsjörg Ubl: The Noric Provincial Army in the Princely Period. In: Zsolt Visy (Ed.) Limes XIX, Proceedings of the XIX International Congress of Roman Frontier Studies held in Pécs, Hungary, Sept. 2003 . University of Pécs, 2005.

- Christine Schwanzar: The Danube Limes in Upper Austria. In: Jutta Leskovar, Christine Schwanzar, Gerhard Winkler (ed.): What we stand on. Archeology in Upper Austria. 2003 (Catalogs of the Upper Austrian State Museum, New Series; 195).

- Gerhard Winkler: Roman roads in Upper Austria. In: Jutta Leskovar, Christine Schwanzar, Gerhard Winkler (ed.): What we stand on. Archeology in Upper Austria . 2003 (Catalogs of the Upper Austrian State Museum, New Series; 195).

- René Ployer: The Norwegian Limes in Austria . Find reports from Austria, Materialhefte series B 3, Österr. Federal Monuments Office, Vienna 2013.

Web links

- Location of the fort on Vici.org

- Castle Linz - The Roman Limes in Austria , accessed on January 3, 2016

- Schlossmuseum Linz , accessed on January 3, 2016

- Roman Linz - web presentation and short film. Created as part of an EU project in cooperation with the University of Vienna , accessed on January 3, 2016

- AIS-OOE Archaeological Information System for Upper Austria ( Memento from November 10, 2014 in the Internet Archive ), on wayback

- "Austrian City Atlas" History of the City of Linz

Remarks

- ↑ Gerhard Winkler: 2003, pp. 137-140.

- ↑ Notitia Dignitatum, Occ. 34, 32.

- ↑ Kurt Genser: 1986, p. 105.

- ↑ Kurt Genser: 1986, pp. 117-118.

- ↑ Erwin Ruprechtsberger: 1997, p. 180.

- ↑ Kurt Genser: 1986, p. 120.

- ↑ … hoc est in pago Trungouue in loco, cui vocabulum est Linze, super magnum flumen Danubium id est ecclesia, que in honore sancti ac beatissimi Martini episcopi .

- ↑ Thomas Fischer: 2002, p. 30.

- ↑ Erwin Ruprechtsberger: 1997, p. 183.

- ↑ a b c d Kurt Genser: 2007, p. 80.

- ↑ Kurt Genser: 2007, p. 79.

- ↑ Kurt Genser: 1986, p. 106.

- ↑ Kurt Genser: 1986, p. 109.

- ^ Find reports from Austria , Volume 39, 2000, p. 40.

- ↑ Erwin Ruprechtsberger: 2003, p. 40 and p. 123–126.

- ↑ Paul Karni sealed: 1952b, p 434 f. and find reports from Austria. Volume 1, 1930-1934, p. 66 and 129.

- ↑ Kurt Genser: 1986, p. 111.

- ↑ Kurt Genser: 1986, p. 112.

- ↑ a b Hannsjörg Ubl: 2003, p. 111.

- ↑ Erwin Ruprechtsberger: 2003, p. 124.

- ↑ Kurt Genser: p. 114.

- ↑ CIL XVI, 174 (128-138 AD) and AE 1988, 915 (135-138 AD)

- ↑ AE 1958, 37 ; Data sheet with images from Ubi erat lupa , accessed on January 3, 2016.

- ↑ AE 1978, 597 and 1982, 757; Data sheet with illustration from Ubi erat lupa , accessed on February 3, 2016.

- ↑ Kurt Genser: 2007, p. 82.

- ↑ Kurt Genser: 2007, p. 83.

- ↑ Occ. 34.32.

- ↑ Erwin Ruprechtsberger: 2003, p. 123.

- ↑ a b c Erwin Ruprechtsberger: 2005, p. 14.

- ↑ a b Erwin Ruprechtsberger: 1997, p. 184.

- ^ Paul Karnitsch: 1956, overview plan p. 259.

- ^ Find reports from Austria : Volume 5, 1946-50, p. 237. Volume 6, 1951-55, p. 107. Pro Austria Romana , Volume 3, 1953, p. 26 and Volume 4, 1954, p. 25, D Schön: 1988, pp. 120-129, Peter Scherrer: 1998, pp. 45-48.

- ↑ Erwin Ruprechtsberger: 2003, p. 125.

- ↑ a b Paul Karnitsch: 1956, pp. 189–260.

- ^ Pro Austria Romana. Volume 5, 1955, p. 31, Paul Karnitsch: 1955.

- ↑ Monument Protection Act ( Memento of the original dated November 15, 2010 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. on the side of the Federal Monuments Office