Künzing Castle

| Künzing Castle | |

|---|---|

| Alternative name | Quintanis / Quintana |

| limes | ORL NN ( RLK ) |

| Route (RLK) | Rhaetian Limes and Danube-Iller-Rhein-Limes / DIRL of Raetia II (route 4) |

| Dating (occupancy) | Domitian, around AD 90 to 5th century |

| Type | a) Cohort and Alenkastell dating from the Middle Imperial period b) Unknown late antique complex |

| unit | a) Cohors III Thracum equitata civium Romanorum , b) Cohors V Bracaraugustanorum , c) Ala prima Flavia Raetorum |

| size | Max. 132.5 × 165.5 m = 2.25 ha |

| Construction | a) wood-earth, b) stone construction |

| State of preservation | No building remains preserved in situ . Flag sanctuary re-walled. |

| place | Künzing |

| Geographical location | 48 ° 40 ′ 6.7 " N , 13 ° 4 ′ 47.7" E |

| height | 309 m above sea level NHN |

| Previous | Small fort Osterhofen-Haardorf (northwest) |

| Subsequently | Batavis Castle (southeast) |

The Künzing Fort was part of the fortress chain of the Rhaetian Limes and is located in the Bavarian district of Deggendorf in the municipality of Künzing .

Built in the late 1st century AD, the complex was probably destroyed by the Alamanni in the 3rd century and then abandoned for a long time. During late antiquity, the garrison site could have been replaced by a fortification that has not been archaeologically proven to this day and which presumably existed until the 5th century. The fort is best known for its mention in the Vita of Severin von Noricum and a large metal hoard, which gives a good idea of the armament and equipment of the mid-imperial auxiliary troops ( auxilia ) on the Rhaetian Limes.

Surname

The u. a. In the Antonini Itinerarium , a travel guide from the 2nd century AD, the name of the fort, Quintana, is derived from a Lusitan cohort stationed here in the 2nd century, according to the prevailing opinion in archaeological research today (see below). The phrase “ad quintanos” - d. H. "At the camp of the fifth" - based. Also in the Notitia Dignitatum , the Künzing location is listed as Quintanis in late antiquity ; this form of name goes back to a place abbreviation ("in Quintana"). The Roman place name was later changed from the medieval form Quinzen over Künzen to today's Künzing, whereby the old-fashioned ending -ing is only an addition of the 19th century.

location

The mid-imperial border fortifications were built at a safe distance from the Danube, which was much closer at the time. Before being regulated, this intervened in the surrounding area with wide loops and oxbow lakes. Quintana was with a multitude of other forts on an important military and trade route that followed the course of the river into the Balkans . The molasse basin of the Alpine foothills formed by the ice age glacier thrust extends southwest and south of the fort , which is characterized by hilly landscapes and sometimes deeply cutting waters. From the castle of the crew on the other side was the mountain ranges of the Barbaricum lying Bavarian Forest Watch. The Dungau , which extends along the Danube , in which the fort was located, is known for its high-yield loess soils . The historian Johannes Aventinus (1477–1534) also mentions a salt spring near Künzing . A corresponding spring still emerges east of the fort today.

Research history

16th to 19th century

The oldest message via Roman finds from Künzing comes from Philipp Apian (1531-1589): "Roman coins, gold, silver, very testify many bronze objects, that at this point Quintiana, a branch of Romans has passed." The agreement of Johannes Aventinus had already recognized Künzing with the ancient Quintiana . The doctor and philologist Thomas Reinesius (1587–1667) later documented a funerary inscription for the 50-year-old Caesius Jarsa , which was later lost and commissioned by his wife Julia Successa . In 1788 Lorenz von Westenrieder (1748–1829) was there. From his own experience, however, he could not confirm the slightest signs of a Roman presence in Künzing, although the pastor told him that, according to some farmers, there were "many stones from ancient times" under the earth .

The last prior of Niederaltaich monastery before secularization , Emmeram Spielhofer (1746–1810), who also dealt with Roman antiquity, mentions two “copper handles” from the Osterhofen area to the historian Joseph Anton von Mussinan (1766–1837) , around six kilometers northwest of Künzing. The prior also reported that the ancient coins and rings with precious stones found in the area by shepherds and peasants had immediately fallen into the hands of goldsmiths and belters. The valuable metal was usually melted down and the stones reprocessed. Spielhofer also reported on a Roman tombstone made from coins that he found himself. He was still able to note the fragmentary inscription "Miles leg. Dec: II." : "I would have liked to have taken this stone with me to the monastery, only hostile hands stole the stone from me." This loss of the find, mainly caused by the local population, included to which she partially opened up additional sources of income, can perhaps explain why research by Professors Andreas Buchner (1776–1854) and Kaspar Pütter in 1819 and 1820 did not reveal any evidence of the Roman past of Künzing. Strangely enough, the clearly visible hollow formed by the former fort trenches in front of the eastern front of the camp also remained undetected. It only disappeared after the canal was built in 1984. The General District Commissioner and District President Adam Joseph Freiherr von Mulzer , who had excavations here from 1829–1831, initially only found a few coins before he came across a “mighty foundation of buildings” with hypocausted rooms in 1830 April 1831 were uncovered. He suspected that the building, which was relatively well documented for the time, had been violently destroyed due to its many traces of ash. Due to the high cost pressure, however, the investigations soon had to be stopped again. The building find is later mentioned several times in the publications as the "legend of a Roman bath" , because u. a. Even research in the summer of 1883 no longer produced any tangible results for this bath. It was not until 1976 that the thermal bath was cut again and in 1978 it was partially excavated.

It was left to the Künzinger cooperator Johann Michael Schmid to discover the fort himself on July 3, 1874 and to expose parts of the fort wall. It was followed in 1897 and 1898 with the first extensive excavations by the grammar school teacher Franz Pichlmayr. At that time, three corner towers, the right side gate (Porta principalis dextra) and the horseshoe-shaped sanctuary with flags were discovered.

20th and 21st centuries

From 1914 to 1928, graves from late antiquity were observed west of the mid-imperial fort. The extensive investigations by the Roman-Germanic Commission provided valuable information about this fort itself. In 1930 the prehistorian Paul Reinecke (1872-1958) published a plan for the fort that was valid for many decades. This was based on the work of the civil engineer Hanns Neubauer (1901–1986) who was busy for decades with the recovery of Roman finds in Künzing. The excavations financed by the German Research Foundation in 1958, 1962 and from 1964 to 1966 under the direction of the archaeologists Hans Schönberger (1916–2005) and Fritz-Rudolf Herrmann provided evidence of a total of four construction periods for the Middle Imperial Camp. Between 1978 and 1979, digging took place again at the presumed late antique location of the fort. In the decades that followed, research concentrated on the area of the camp village, sometimes in large-scale excavation campaigns. In 2003, employees of the Deggendorf District Archeology found traces of a wooden Roman amphitheater, which was partially uncovered by 2004. In 2009 more graves were discovered in the eastern sector.

development

1st to 3rd century

The fort was founded together with the camp village (vicus) around 90 AD. Its first occupation force, a Thracian cohort , was assigned to the Jewish War of Emperor Hadrian in the east from 132 to 136 AD . After their return, the Gnotzheim fort was the unit's new station. In the meantime, the Künzinger fort was probably still occupied by a smaller vexillation before it was completely rebuilt by the Lusitanier troops who were newly moving into the fort. The fundamental renovation of the fort was also necessary due to the extensive border security measures under Emperor Antoninus Pius (138-161). Under his government, the external border of the Roman Empire was additionally reinforced in many areas. Like Künzing, numerous other forts received outer walls, towers and gateways built from stone and bricks in place of the wood-earth fortifications. After the assassination of Severus Alexander in 235 and the ensuing turmoil of the civil war during the military emperor's time, the Rhaetian border defense organization collapsed almost completely, as it was no longer possible to repair fortifications that had been destroyed or become unusable.

During the new Persian Wars in the years around 242/244 AD - after 233 - there was a second large-scale Alemannic attack against the Rhaetian and Upper Germanic Limes, which led to its collapse in many parts of the Limes and must have had devastating consequences for Künzing. The archaeologist and numismatist Hans-Jörg Kellner identified this idea on the basis of many coin finds. For example, the youngest coin in the Gunzenhausen fort was an Antoninian from the year 242, and the final coin in the Kösching fort was set to the summer of 241. In 242/243 the Regensburg small fort Großprüfening as well as the extensive Roman settlement near Pocking , district of Passau , and other places were overrun. In Pocking, the final layer of fire hid an Antoninian of 241/243 or 240, which had only been in circulation for a short time. In Künzing itself - an ace from the years 243/244 - almost fresh from the stamp - was found near the weapons and metal hoard mentioned below . The building inscription from the small bath of the Jagsthausen fort , which was created between 244 and 247, stands for the time of the reconstruction after the Alamannensturm .

At the latest with the subsequent Alemanni attack in the context of the Limesfall around 259/260, the fort was completely burned down and had to be abandoned.

4th to 7th century

For the late Roman period in Raetia II and Noricum ripense , the mention of the fort in the biography of Severin von Noricum is particularly important. For the westernmost oppidum mentioned in Severin's vita , the conditions for its continued existence were much less favorable than, for example, in Passau. Its location on the great Danube plain made it an outpost of the constantly dwindling Roman sphere of influence in the 5th century, which Severin was particularly keen to get.

Between 455 and his death in 482, Severin stayed mainly in the area between Quintanis , Iuvavum and Asturis . This passage from Vita Sancti Severini gives an insight into the living conditions of the late period of the Roman Danube Limes and the difficult struggle for survival of some Christian communities in the turmoil of the migrations of the 5th and 6th centuries. When Severin arrived at Batavis / Boiotro (in loco nomine Boiotro ) on one of his hikes around 455 , the residents of the oppidum Quintanis invited him to visit them too. The Vita also tells of a presbyter named Sylvanus, who presided over the local community as the spiritual leader. Mention is also made of his deacon by the name of Maternus and a small wooden church which, a bit away from the fort, was close to a brook and was therefore often flooded. Due to the constant threat from the Alamanni, Severin was forced to bring the Romanesque population of Quintanis, Batavis (Passau- Niedernburg ), Batavis (Passau- Innstadt ) and Ioviaco (Schlögen) to Lauriacum in 476 . They were later brought from there to Favianis , which was under the protection of the Rugians . In 488 AD most of the Norican novels were finally settled in Italy on the orders of Odoacer .

Doubts about the complete demise of the Roman community in Künzing announced by Severin should nevertheless be in order. The late medieval Quinzina still played an important role as the administrative center and gave the name to the Künzinggau. Its importance is also underlined by the upgrading of the Romanesque parish church of St. Laurentius to a basilica. In the course of the renovation of the church in the 1970s, W. Haas was able to recover ceramic shards from a smooth-decorated bowl that came from Carnuntum in the late 5th century. The trade connections of Künzing to the other, still existing Romanesque settlement centers in the east are unlikely to have been completely torn down, just as the Romanesque people on the upper Danube did not suddenly and without a trace disappeared. Nevertheless, it can be seen from the findings that the residents of Quintanis at that time only had a very limited economic space available. The citizens of this epi-urban settlement must have relied on sources of food and livelihood other than just agriculture. The high-yield loess soils around Quintanis were a great temptation for land-seeking tribes to settle here. The preponderance of Germanic new immigrants can also be seen particularly well from the extent of their row grave fields. When the Germanic conquest of the land began was long controversial until 1980 the row cemetery of Straubing- Alburg was discovered, which was occupied from the late 5th century and could be assigned to those Alemanni mentioned by Eugippius under their King Gibauld, who presumably the Quintanians so hard had pressured.

The settlement finds from the 6th and 7th centuries are no longer recognizable as such as "purely Romanesque" (excavations south of the fort on the Ohebach), but the burials of this time are clearly still Romanesque in character.

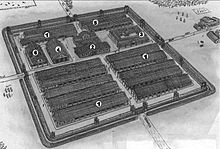

Fort

The Künzinger fort was a classic rectangular complex with rounded corners (playing card shape), as was typical for the early and middle imperial period. His remains are in the south of today's town center. The fort area extended on both sides of the main road in an even rectangle of 132.5 × 165.5 m and borders on the parish church of St. Laurentius in the north and the school building in the southeast. With an area of almost 2.25 hectares, it offered space for a crew of around 500 men. The interior of the fort was divided by a right-angled cross between the two main streets of the camp, aligned with the four gates. The main gate was facing the enemy, from which the Via principalis led to the staff building ( Principia ) in the center of the camp , around which the other buildings were grouped.

Wood-earth period

In its first construction period from around 90–120 AD, the fort was only protected by a mound built on the inside against a simple palisade wall with a pointed ditch in front, so in the second construction phase the defense system was extensively reinforced and changed. The second construction phase, which was to be scheduled from around AD 120 to 135, had a wood-earth wall with a vertical front and rear (box construction) 4.80 m wide, in front of which two weir ditches were dug. For these two construction periods, the internal structures could also be assigned their function with some certainty. In the northern section of the camp area (Praetentura) there were elongated buildings that were identified as barracks with ten residential units (Contuberniae) for six to eight men. In the rear, southern area of the fort (Retentura) , at the intersection of the two main road axes , which were only slightly north-south and west-east oriented, was the headquarters and administration building (Principia) of the fort, to the west of it was the commandant's house (Praetorium) . A storage building (Horreum) and the camp hospital (Valetudinarium) were discovered east of the Principia . The latter had a rectangular floor plan. The sickrooms were on either side. At the end there was a latrine and in the entrance area there was a separate room that was interpreted as a treatment room. These buildings bordered two larger double barracks in the south, which are interpreted as horse stables (stables) and crew quarters .

A communal latrine was also found in Künzing. It consisted of an elongated pit, a simple wooden structure with seating and a roof (post holes). After the pit was filled, a new one had to be dug and the old one filled in. These types of latrines were preferably located close behind the walls on Wallstrasse (Via sagularis) . It was also proven, for example, on the basis of the excavated pit filling. The outlet in Künzing was 1.4 meters deep, 14 meters long and two meters wide. The extent of the pit's contents shows that it must have been in operation for many years.

Stone period

In the third construction phase, around 150/160 AD, the fort was probably completely rebuilt in stone by the 5th cohort from Bracara Augusta , while the interior structures were again only made of wood. A stone enclosure wall replaced the previous wood-earth wall, up to five trenches formed the obstacles to approach, the outermost of which was around 42 m in front of the wall. From the former stone wall only rubble stones and the gravel fillings of the foundations had survived, a stone layer of the rising rubble stone masonry could only be documented at a single point. The other stones of the fort wall may have been reused as valuable building material for other buildings after the fortress was finally abandoned. The fort appears to have been violently destroyed for the first time in the years around 200 AD.

During the subsequent reconstruction, the fourth construction period of the Künzinger fort, it was only surrounded by a ditch. As with its predecessor, little is known of the interior of the last construction phase of the fort. There is evidence that the rear part of the Principia was partly rebuilt in stone. This expansion affected both the flag sanctuary with its cellar and its semicircular apse , as well as two rooms on the two outer flanks, which received a hypocaust and canal heating . The also newly built vestibule was still made of wood and its narrow sides were evidently in line with the service and administration rooms behind. This fort was also attacked. It was destroyed no later than AD 259/260. The cause is suspected to be an attack by the Alemanni. The previous location was then finally given up.

From a pit next to the Principia comes an important armory , in particular daggers ( pugiones ) , fragments of bronze statues and horse harness, which are among the most important finds of this type in the Rhaetian Limes (see below).

Late antiquity

The late Roman fort, attested by the Notitia Dignitatum and the Vita Severini , was part of the Danube-Iller-Rhein-Limes in the province of Raetia II and, as it appears, was built to the northwest of its predecessor and thus much closer to the Danube bank, at the same time it was built there also a new burial ground for its residents. This location has been determined since 1976, when it was found that the late antique and early medieval finds in the area of the lowlands to the Danube, in a zone around 200 meters northwest of the north gate of stone fort I, were increasing in number. The archaeological excavations in 1978 and 1979 also support this theory. At that time, a large number of small finds from the 4th to 5th centuries came to light. The population living in the vicinity of the late antique garrison left their settlement areas, which were threatened by marauding Germanic tribes, at an unknown point in time and took refuge behind their walls. So the fort was probably transformed into a fortified settlement and thus largely lost its former, purely military function. This scenario, which has been proven for numerous locations along the Danube Limes, should also apply to Künzing.

The road leading from the porta praetoria of the medieval fort also turned southwest after leaving the gate and apparently led to a port that was probably in the immediate vicinity of the late Roman fort. In the 6th or 7th century, the village of Arbing was built northwest of Künzing ; it was directly connected to Künzing by a straight line via Langburg. After the early Middle Ages, this path suddenly became through the o. Danube loop interrupted. If you extend the line to Künzing, it ends exactly at the presumed location of the late antique fort.

To the west of the zone in question, the Ohebach or the Angerbach flowed into what was then an oxbow lake, and the small finds from late antiquity also ended abruptly at what was once the bank. This finding also confirms the statements of Eugippius in the Vita; Quintanis is described here as lying on one level, directly on the banks of the Danube. It was often hit by floods because the Buscina river backed up when the Danube floods. This can only refer to today's Ohebach, as it is the only body of water in the vicinity and flowed into the Danube bed at that time. These frequent flood catastrophes already contained the seeds for the demise of the late Roman fort; it was probably completely eroded from the oxbow lake or a bend in the Danube up until the Middle Ages.

garrison

The fragments of military diplomas and brick stamps found here provide indications as to which divisions of the Roman army in Raetia were stationed in the Künzinger fort . In 1983 a fragment of a military diploma was discovered in the eastern vicus area, which, like the one mentioned below, was discovered in 1996, came from the reign of Emperor Antoninus Pius and was issued on September 7, 144. As in the much better preserved diploma from 160, a no longer identifiable person from the people of the Celtic Runicaten, who lived in the Rhaetian-Vindelican area, received Roman citizenship at the end of 25 years of service. Brick stamps with the abbreviation of the 3rd Italian Legion were also found in Künzing, but it was not stationed here, but in the Legion camp of Regensburg . However, the stamps only show that Künzing obtained its building material, like the other Eastern Forts, from the large legionary brickworks in Bad Abbach near Regensburg.

| Illustration | Time position | Troop name | comment |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1st to 2nd century AD |

Cohors III Thracum civium Romanorum equitata to torquata ("the third partially mounted Thracian cohort of Roman citizens") |

This unit is tangible as the first troop stationed in Künzing. Their soldiers originally came from what is now Bulgaria . Their abbreviation COH III THR CR has been preserved on several brick stamps. Such a force (cohors quingenaria equitata) was in its full strength usually from about 360 footsoldiers (six Centurions - centuriae - each with 60 men) and 120 riders (four towers - turmae - of 30 people). As finds of arrowheads and bone reinforcements for the bow ends show, some soldiers of the Künzinger troop were - at least temporarily - apparently armed with bows and arrows. Around 135 or a little later the Thracians were posted to the Gnotzheim fort . | |

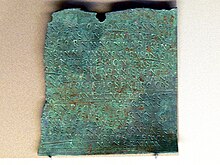

Military diploma of Victor who served in the Bracaraugustonorum V, 160 AD (Quintana Museum)

|

2nd century AD |

Cohors V Bracaraugustanorum ("the 5th cohort from Bracara Augusta ") |

This occupation force was stationed in Künzing from the middle of the 2nd century AD. Presumably she was lying in the Gnotzheim fort before her assignment in Künzing. The unit is mentioned on a military diploma fragment from December 18, 160, discovered in Künzing in 1996. Victor, son of Sendusis of the Runicaten people, former soldier of the Cohors V Bracaraugustanorum , who at that time was under the command of Iulius Celerinus , received Roman citizenship and the right to a full marriage with his previous partner Prima after 25 years of service. Daughter of Masus. The 5th cohort, which after their barracking in Künzing possibly built the stone fort of the third period between 140 and 150 AD, obviously gave Quintana its name: Castra quintana = fort of the "fifth". |

Chape of a sword scabbard

|

Late antiquity | Alae primae Flaviae Raetorum ("the first Flavian cavalry squadron of the Raetians") | According to the Notitia Dignitatum , a Praefectus was stationed in Quintanis as commander of a cavalry troop in late antiquity . This cavalry troop, which was probably set up in the middle of the Imperial Era, was part of the Limitanei from the 4th century AD and was under the command of the Dux Raetiae . |

Vicus

The buildings ( strip houses ) of the extensive civil vicus surrounded the camp in a semicircle from northwest to east. As an important local economic factor, the Künzinger Fort also attracted traders, innkeepers and craftsmen to take care of the soldiers stationed here. In the course of time a civil settlement developed around the fort, in which the above-mentioned. and above all the families of the soldiers settled. Numerous small finds of tools bear witness to the stay of various professional groups such as bricklayers, carpenters, blacksmiths and tanners in the Künzingen camp village. Since the wood used in the floor is long gone, only small metal parts such as B. decorative handles, box fittings and handles and furniture feet made of bronze to the fore. A large number of keys made of bronze, bone and iron, lock bolts and lock fittings also belong to this repertoire. Iron knives - some with ornate handles made of bone - and small bronze or silver spoons have survived in particular.

Thermal bath

In 1830 and 1978 the remains of a thermal bath were partially uncovered during excavations west of the fort area in Künzing. It was a brick and timber-framed building of the "row type", which is common on the northern Limes, with a barrel-shaped roof probably made of tuff. The building, around 50 meters long and 13 meters wide, stretched from today's federal highway in a northerly direction to the former Roman road. Row type means that its rooms are lined up according to the bath sequence. From a changing room, the visitor first entered the cold bath (frigidarium) ; After that, individual pools with water at different temperatures followed, and a sweat bath (tepidarium) was also available here. The water was heated by a heating system (praefurnium) in the southern part of the building through heating channels (hypocaust) below the floors . The findings also suggest that the Künzinger Therme was probably unusually well equipped for the bath of a cohort fort, apparently with glass windows and painted walls, among other things. A brick stamp indicates that the bath could have been built by a vexillation of the 3rd Legion. His bricks were not imported, however, but seem to have been fired on site.

amphitheater

In 2003, employees of the Deggendorf district archeology found post pits east of the fort , which were arranged in a rounded shape. During the subsequent excavations in autumn of the same year, a black and humus soil segment was uncovered, which was located within the oval formed by the pits. This led to the conclusion that the fort and vicus of Künzing must have also included an amphitheater made of wood . The findings of the archaeological excavations of the amphitheater up to 2004 showed that the arena was 35 x 30 meters, a total of 46 x 40 meters. For the out-of-town amphitheater north of the Alps, a hollow was usually first dug and the overburden was then heaped up as a substrate for the grandstand. From the wooden stands erected on it, the archaeologists found traces of three oval circles around the arena, each with 30 post holes in the support structure.

The grandstands had an angle of inclination of an estimated 30 to 35 degrees, an average seat height of almost 50 centimeters and a depth of at least 75 centimeters. The minimum height of the seats, based on the level of the arena floor, was assumed to be around three meters. The main entrances were probably in the middle of the narrow sides. The reconstruction of the model for the museum is based on the preserved stone models, in which the entrances occupy a yoke between the rows of posts surrounding them. The arena of Quintanis offered space for around 800 spectators, so it was probably also accessible to the civilians living in the vicinity of the camp. When the excavations stopped in 2004, around a quarter of its total area had been exposed.

Mithraeum

In 1998, a two-phase Mithra temple made of wood was discovered just a few meters from the eastern boundary of the civil settlement . In the first construction phase, a small vestibule led to the cult room, which offered space for around 17 people. It was furnished with the wide central aisle that is common for Mithras shrines and side benches. A rectangular niche on the front wall of the central aisle originally housed a cult image or an altar of the deity. After the Mithraum was destroyed by a fire, the sanctuary was rebuilt in the same place. It was now slightly larger than the previous building and offered space for up to 23 people. Two consecration altars were found on its front, which were probably set up here during the second construction period. One of them still bore a completely preserved dedicatory inscription. The small finds (e.g. oil lamps, a short sword and a knife) come from the inventory for the cult ceremonies. Drinking cups and cult vessels with snake ornaments were probably used at the common cult meals.

Hoard finds

|

Found material Principia

In the finds from the west side of the armory of the principia were the fragments of parade armor and harness. The hoard from the eastern side consisted of:

of tools:

on other objects:

There were also individual items, such as a wheel rim fitting and a wheel hub, half of a wooden spade fitting, a saw blade and some smaller, mostly fragmented devices such as:

finally u. a. a large number of fittings such as lock plates, door hinges, hinges and nails, which probably came from the burned down buildings of the fort. |

The iron hoard of Künzing was discovered in 1962 during the excavations of Hans Schönberger east of the Principia , packed tightly together in a shallow pit. It is the largest Roman iron hoard found north of the Alps to date and has a total weight of 82 kilograms. The top pieces were only 20 centimeters below the ground. Metal objects of the Roman army had never been recovered in such quantity and variety. The finds made possible a comprehensive overview of the equipment inventory of the Künzinger crew. In addition to numerous metal objects, it mainly contained a wide variety of weapons. When they were found, the finds showed clear signs of fire. It is believed that the valuable metal was hidden here by looters after the castle was destroyed. This probably happened in connection with the great Alemanni invasion after the middle of the 3rd century. The accompanying find of a coin of Gordian III. is also the latest coin from the fort area.

Other hoard finds are known from Künzing, including two bronze horts, which also contained partially melted objects. These finds from the fort and civil settlement can probably also be linked to the fall of the fort in the 3rd century AD. The complexes of finds provide some insight into the life of the residents of the camp service. About 100 years before the final destruction of the medieval castle, a leather pouch filled with coins was buried, the contents of which - 42 silver denarii - could be gleaned from a field in 1991. The most recent coinage dates from the time of Emperor Hadrian, which means that he can be dated to around the middle of the 2nd century. However, its concealment does not necessarily have to be traced back to armed conflicts; it was then common practice to bury one's savings as a precaution. The same is probably true of a second find made in the civil settlement. In this case it was a piece of chain mail rusted together in a lump as well as the corner and lock fittings of a wooden box in which it had been carefully placed for safekeeping, a horse tack and round, arched bronze discs that might have belonged to a horse's bridle, rounded off the find complex. The unity of the found material does not indicate a hastily and indiscriminately assembled ensemble. Presumably in this case we have the equipment of a soldier or veteran of the cavalry.

More militaria

During the various excavations, a large number of small parts of the soldiers' equipment came to light. Some were used as individual decorative elements for weapon belts (cingulum) and in some cases were also provided with the names of their previous owners. Other examples of these decorations were part of the horse bridles of the Künzinger equestrian department.

Ceramic spectrum

In terms of ceramics, it was mainly simple plates, saucepans, their lids and tripod pots that came to light. Also Mortars were part of the essential equipment of the kitchens in Künzinger camp village; in them mainly spices and herbs were crushed. The dishes for daily use were probably mainly made in the local pottery workshops, but these have not yet been localized. Numerous fragments of olive oil amphoras were also discovered in the Künzinger civil settlement. The manufacturer's stamps on the handles indicated that the oil imported to Künzing had been bottled in southern Spain. The terra sigillata fragments recovered in large numbers in Künzing are also imported goods. a. from Arezzo in northern Italy. In the 1st century AD, however, most of these goods were already being produced in southern and eastern Gaulish factories. The owners of these factories also operated branches in the Rhine-Main area. In particular, producers from Rheinzabern ( Tabernae ) have become the main suppliers for Künzing from the middle of the 2nd century. In contrast to the Terra Sigillata , the so-called Rhaetian ceramics are fine ceramics produced on site. With the exception of the base, the vessels were covered with a glossy black clay . They often had circumferential geometric stripes that were incised or attached with a running wheel. A figurative ornament was relatively rare, such as B. a mug decorated with hunting scenes from Künzing, this was u. a. viscous clay dripped onto the still unfired vessel. Typical forms of this ceramic were drinking cups with a narrow base and a wide belly as well as flat bowls. The glass vessels mainly came from the Rhaetian provincial capital, Augusta Vindelicorum (Augsburg). As with the oil amphoras, these were mainly transport bottles in which anointing oils or perfumes were stored and traded on.

Cult and religion

Only a few finds are known from Künzing that are related to Roman cult practices. Particularly noteworthy here is the depiction of the god of war Mars on a bronze horse forehead armor from the Principia hoard. There was also the head of a small lime statue of Mercury , who, according to archaeological evidence, was the most widely revered god in the northern Roman provinces. A bronze statuette is interpreted as Aesculapius , the god of healing. An incised drawing on a silver-plated bronze stud represents Sol Invictus and is used today as the logo of the Künzinger Roman Museum. In the 3rd century, the deity was elevated to the status of the highest imperial god by Emperor Elagabal . Sol wears a seven-pointed halo on it; next to him a whip is depicted in the background, it is supposed to symbolize his function as driver of the sun chariot.

Burial grounds

In Künzing, grave finds were uncovered in two places south and east of the mid-imperial vicus. The urn and incendiary graves on the eastern edge are typical of the custom of cremation that is common in the northern Danube provinces. The grave field in the east is unique in southern Germany due to its size and unusually long occupancy of over 600 years (since the Bronze Age ). In the course of construction work in 2009, archaeologists discovered 30 more Roman cremations in the east of Künzing. Excavation manager Sabine Watzlawik found u. a. Ceramic shards, burned bones, glass fragments, iron objects, wells, cellars, remains of pit houses and other Roman settlement finds. According to the funeral rite of the time, the dead were first burned on a stake. The ceramic shards found suggest that some of the ashes of the dead were then scattered on the burial ground. Nevertheless, urn burials could also be found. The finds were cleaned and then handed over to the museum in Künzing for safekeeping.

In addition to the late Roman fort to the northwest of the old garrison near the Danube, a new burial ground was also built. Excavations that took place in this area between 1914 and 1928 uncovered body graves from the second half of the 4th century.

Hints

Künzing is one of the most archaeological places in the Deggendorf district. The Quintana Museum is a partner museum of the State Archaeological Collection and a member of the “Archeology in East Bavaria” museum association. It exhibits important finds from the prehistory and early history of the region and prints on Saint Severin von Noricum . Above all, the museum offers a representative selection from the rich spectrum of Roman finds, overview panels, graphics and models of military life in the fort and everyday life in the civilian settlement. In addition to a reconstruction model of the amphitheater, the Quintana Museum is also showing a short film with the CAD simulation of the historical facility. Various projects offer further insights into Roman history, such as the “Romans in Künzing” themed trail, which leads visitors to the most important Roman monuments in the community.

Monument protection and remains

The Künzing Fort is a registered ground monument within the meaning of the Bavarian Monument Protection Act (BayDSchG). Investigations and targeted collection of finds are subject to authorization, accidental finds must be reported to the monument authorities.

After the excavations, only the newly built apse of the stone flag shrine remained of the fort. They were moved from their location to the courtyard of the Künzinger school and are not open to the public. In order to make the original find place of the fort bath visible, the caldarium (warm bath) and tepidarium (leaf bath) were indicated with plates in the green area behind the savings bank at Osterhofener Straße 4.

See also

literature

- Rainer Christlein: The Rhaetian cities of Severins, Quintanis, Batavis and Boiotro and their surroundings in the 5th century from an archaeological point of view . In: Land Oberösterreich, Office of the Upper Austrian Provincial Government (Hrsg.): Severin. Between Roman times and the Great Migration . Linz 1982, pp. 240-244.

- Peter Connolly: The Roman Army , Tessloff Verlag, Hamburg 1975, p. 56, ISBN 3-7886-0180-9 .

- Thomas Fischer : The Roman fort bath of Künzing. In: Bayerische Prognistorblätter Vol. 50 (1985) pp. 247-286.

- Thomas Fischer: A new middle-imperial fire burial ground from Künzing. In: Archaeological preservation of monuments in Lower Bavaria. (1985) pp. 174-178.

- Thomas Fischer, Erika Riedmeier-Fischer: The Roman Limes in Bavaria. Verlag Friedrich Pustet, Regensburg 2008, ISBN 978-3-7917-2120-0 . Pp. 179-181.

- Thomas Fischer: Late Roman settlement finds from Künzing / Quintanis. In: Bavarian history sheets. No. 54, 1989. pp. 153-187.

- Thomas Fischer: Two new metal collection finds from Künzing / Quintana (district of Deggendorf, Lower Bavaria). In: Searching for traces. Festschrift for Hans-Jörg Kellner on his 70th birthday. Catalog of the State Prehistoric Collection. Supplement 3. 1991. pp. 125-175.

- Werner Friedenberger: Our home - a historical gem , publisher: Künzing municipality, p. 23.

- Robert Ganslmeier, Karl Schmotz: The mid-imperial castle Künzing. In: Archaeological monuments in the Deggendorf district. No. 8. (3rd revised new edition) Deggendorf 2003.

- Anna Sybille Hannibal-Deraniyagala: The Bavarian burial ground of Künzing-Bruck, district Deggendorf. In: Bonn contributions to prehistoric and early historical archeology. No. 8 (2007).

- Hans-Jörg Kellner: The great crisis in the 3rd century. In: Wolfgang Czysz u. a .: The Romans in Bavaria. License edition of the 1995 edition, Nikol, Hamburg 2005, ISBN 3-937872-11-6 .

- Ursula Koch: The grave finds of the Merovingian period from the Danube valley around Regensburg. Germanic Monuments of the Migration Period , Series A, Volume 10, 1968.

- Felix Mader: Die Kunstdenkmäler von Bayern, Ortsamt Vilshofen , Oldenbourger Wissenschaftsverlag, 1982, pp. 182-183.

- Franz Pichlmayr: Investigation of the fort near Künzing (Lower Bavaria, Vilshofen district office) . In: Correspondence sheet of the "West German Journal for History and Art" . 16, 11 (1897) pp. 209-213.

- Dieter Planck , Andreas Thiel : Das Limes-Lexikon, Rome's borders from A to Z. C. H. Beck, Munich 2009, ISBN 978-3-406-56816-9 . P. 73.

- Paul Reinecke : New finds from the Raetian border fort Quintana. In: Germania 14, 1930. pp. 2-11.

- Johann Michael Schmid: The Roman Castell in Künzing. In: Negotiations of the Historical Association for Lower Bavaria. Vol. 19, 1875. pp. 147-154.

- Sabine Rieckhoff-Pauli: Roman settlement and grave finds from Künzing, district Deggendorf. In: Bavarian history sheets. Vol. 44 (1979) pp. 79-122.

- Sabine Rieckhoff-Pauli: The 1976 excavations in Quintanis-Künzing. In: Contributions to topography and. History of Roman towns in Lower Bavaria. Beil, 1976, pp. 44-64.

- Fritz-Rudolf Herrmann : The excavations in the Künzing-Quintana fort. Stuttgart 1972 (Small writings on the knowledge of the Roman occupation history of Southern Germany. 8) .

- Fritz-Rudolf Herrmann: The iron hoard find from the Künzing fort. In: Saalburg-Jahrbuch 26, 1969.

- Hans Schönberger, Fritz-Rudolf Herrmann: The Roman fort Künzing-Quintana. Report on the excavations from 1958 to 1966 . In: Annual Report of the Bavarian Heritage Monument Maintenance 8/9, 1967/68, pp. 37–86.

- Cris Schuhmann: Excavations in Bavaria , Bavarian Office for the Preservation of Monuments, Verlag Münchner Buchgewerbehaus, p. 28.

- Karl Schmotz, Sabine Watzlawik: New Roman cremation graves - investigations in the eastern burial ground of Künzing. Deggendorf district, Lower Bavaria . In: The Archaeological Year in Bavaria 2009. Stuttgart 2010, pp. 100–103.

- Karl Schmotz: The Ostvicus von Künzing: location, extent and "special facilities". In: Andreas Thiel (Ed.): Research on the function of the Limes. Contributions to the Limes World Heritage Site , 2, 2007, pp. 132–149.

- Karl Schmotz: The wooden amphitheater of Künzing, Deggendorf district. State of knowledge and first reconstruction approaches after the site work was completed in 2004. In: Lectures of the 24th Lower Bavarian Archaeological Day. Leidorf, Rhaden 2006, ISBN 3-89646-235-0 , pp. 95-118.

- Karl Schmotz: The Mithraic temple of Künzing, Deggendorf district. In: Lectures of the 18th Lower Bavarian Archaeological Day. Leidorf, Rhaden 2000, ISBN 3-89646-229-6 , pp. 111-143.

- Hans Schönberger : Kastell Künzing-Quintana. The excavations from 1958 to 1966. Mann, Berlin 1975, ISBN 3-7861-2225-3 (Limes research 13) .

- Sebastian C. Sommer : The Romans in Künzing - Ways to a virtual reconstruction of the fort vicus. In: Report of the Bavarian soil monument preservation. No. 49, 2008, p. 107 ff.

- Festschrift for the inauguration of the Künzing elementary school , 1966

Remarks

- ↑ ND occ. XXXV, 10.

- ^ Eva Bayer-Niemeier: The Roman fort In: Museum Quintana - Archeology in Künzing. Guide through all departments 2004.

- ↑ Scholarly Ads. Published by members of the royal. Bavarian Academy of Science. Vol. 25 (Jul-Dec). k. Central-Schulbuchdruckerey, Munich 1847, p. 726.

- ↑ Karl Schmotz: Research into the early history of Künzing from the beginnings to the end of the 19th century. In: Deggendorfer Geschichtsblätter. Issue 7, 1986, p. 160.

- ↑ Communications about Lower Bavaria in Roman times. In: Negotiations of the Historical Association for Lower Bavaria. Vol. 9. Josef Thomann'sche Buchhandlung, Landshut 1863. P. 357.

- ↑ a b Treatises of the philosophical-philological class of the royal. Bavarian Academy of Science. Vol. 17. Munich 1884. p. 237.

- ↑ Karl Schmotz: Research into the early history of Künzing from the beginnings to the end of the 19th century. In: Deggendorfer Geschichtsblätter. No. 7, 1986. p. 161.

- ↑ About the castra quintana; from the diary of k. Commissioner General and Government President Ms. v. Mulzer ect. In: Negotiations of the Historical Association for Lower Bavaria. Vol. 2 and 3. Josef Thomann'sche Buchhandlung, Landshut 1847. pp. 1–6.

- ↑ Scholarly Ads. Published by members of the royal. Bavarian Academy of Science. Vol. 25 (Jul-Dec). k. Central-Schulbuchdruckerey, Munich 1847. pp. 717–718.

- ↑ Karl Schmotz: Research into the early history of Künzing from its beginnings to the end of the 19th century. In: Deggendorfer Geschichtsblätter. No. 7, 1986. p. 165.

- ^ A b Hans Schönberger, Fritz-Rudolf Herrmann: The Roman fort Künzing-Quintana. Report on the excavations from 1958 to 1966 . In: Annual Report of the Bavarian Heritage Monument Care 8/9, 1967/68, pp. 37–86; here: p. 40.

- ↑ Ursula Koch: The grave finds of the Merovingian period from the Danube valley around Regensburg. Walter de Gruyter. Berlin 1968. p. 237.

- ^ Hans Schönberger, Fritz-Rudolf Herrmann: The Roman fort Künzing-Quintana. Report on the excavations from 1958 to 1966 . In: Annual Report of the Bavarian Heritage Monument Care 8/9, 1967/68, pp. 37–86; here: pp. 38–39.

- ↑ Thomas Fischer, Erika Riedmeier-Fischer: The Roman Limes in Bavaria. Verlag Friedrich Pustet, Regensburg 2008, ISBN 978-3-7917-2120-0 , pp. 179-180.

- ↑ Max Spindler: Handbook of Bavarian History. Volume I: The old Bavaria of the tribal duchy up to the end of the 12th century. C. H. Beck, 1981.

- ^ Dietwulf Baatz: Roman roads in the Ries. In: Guide to the prehistoric monuments 41. Volume 2. Nördlingen, Bopfingen, Oettingen, Harburg. Verlag Philipp von Zabern, Mainz 1979. p. 264.

- ↑ Robert Roeren : On the archeology and history of Southwest Germany in the 3rd to 5th century AD In: Yearbook of the Roman-Germanic Central Museum Mainz. 7th year. Rudolf Habelt Verlag, Bonn 1960. p. 217.

- ↑ Thomas Fischer, Michael Altjohann: The Roman Provinces. An introduction to their archeology . Konrad Theiss Verlag, Stuttgart 2001. ISBN 3-8062-1591-X . P. 132.

- ↑ Hans-Jörg Kellner: The Roman settlement near Pocking (Lower Bavaria) and its end. In: Bavarian History Leaflets 25, 1960, pp. 132-164.

- ↑ CIL 13, 6562 ( Figure ( page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. ).

- ↑ Thomas Fischer: Comments on the archeology of Severin's time in Künzing and Passau . In: Egon Boshof, Hartmut Wolff (ed.): Christianity in the Bavarian region. From the beginning to the 11th century Cologne / Weimar / Vienna 1994, ISBN 3-412-13993-9 , p. 93.

- ↑ Ursula Koch, 1968.

- ↑ Rainer Christlein, 1982, pp. 244–245.

- ↑ Rainer Christlein, 1982, p. 242.

- ↑ Peter Connolly : The Roman Army . Hamburg 1975, p. 39.

- ↑ a b c d e Thomas Fischer, Erika Riedmeier-Fischer: The Roman Limes in Bavaria. Verlag Friedrich Pustet, Regensburg 2008, ISBN 978-3-7917-2120-0 , p. 180.

- ^ Fritz-Rudolf Herrmann: The iron hoard found from the Künzing fort In: Saalburg-Jahrbuch 26, 1969, pp. 129–141.

- ↑ Rainer Christlein, 1982, p. 240.

- ^ AE 2004, 1065 .

- ^ Karlheinz Dietz In: Ostbairische Grenzmarken. Passau yearbook for history, art and folklore . Volume 46, Verlag des Verein für Ostbairische Heimatforschung, 2004, pp. 14–15.

- ↑ a b Dietwulf Baatz: The Roman Limes. Archaeological excursions between the Rhine and the Danube . Mann Verlag, Berlin 1993, ISBN 3-7861-1701-2 , p. 332.

- ↑ AE 2000, 1139 ; in the list of troops V Bracaraug (ustanorum) , in the copy for the recipient [coh (ortis) V Br] acaraug (ustanorum) and coh (ortis) VB [r] acarau [g (ustanorum)] .

- ^ Vera Romeu: Ennetach Roman Museum. Not easy, the gladiatorial life… In: Schwäbische Zeitung of April 8, 2009; Karl Schmotz : First results of work on the amphitheater in Künzing, Deggendorf district . In: Karl Schmotz (Ed.): Lectures of the 23rd Niederbayerischen Archäologentag Leidorf, Rahen 2005, ISBN 3-89646-234-2 , pp. 149–166.

- ^ The archaeological year in Bavaria 2003. Theiss, Stuttgart 2004, ISBN 3-8062-1899-4 . P. 5 (back cover).

- ↑ 48 ° 40 '11 " N , 13 ° 4' 49" O .

- ↑ Fritz-Rudolf Herrmann : 1969, pp. 129–141; Hans-Jörg Kellner: 2005, p. 329 f.

- ↑ Andreas Windpassinger: Over 30 graves discovered in Künzing . In: Vilshofener Anzeiger of October 26, 2009, p. 27.

- ↑ Ursula Koch: The grave finds of the Merovingian period from the Danube valley around Regensburg. Walter de Gruyter. Berlin 1968. p. 237.

- ↑ Thomas Fischer, Erika Riedmeier-Fischer: The Roman Limes in Bavaria. Verlag Friedrich Pustet, Regensburg 2008, ISBN 978-3-7917-2120-0 , p. 181.

Web links

- Quintana Museum

- Model of the fort in the Quintana Museum

- Model of the Künzinger amphitheater

- Foundations of the flag shrine in the courtyard of the Künzinger school

- Museum Quintana in Künzing - from the series “Wastl on the move” on YouTube

- Digital archeology website: Roman fort and vicus Künzing, 3D reconstruction for the Roman museum Quintana

- Digital archeology website: Künzing thermal baths, 3D reconstruction