Jagsthausen Fort

| Jagsthausen Fort | |

|---|---|

| limes | ORL 41 ( RLK ) |

| Route (RLK) |

Upper German Limes , Front Limes, route 8 |

| Dating (occupancy) | around AD 160 to AD 260 at the latest |

| Type | Cohort fort |

| unit | Cohors I Germanorum (equitata) civium Romanorum |

| size | around 185 m × 152 m (= approx. 2.9 ha) |

| Construction | stone |

| State of preservation | completely built over; reconstructed foundations of the large fort bath visible |

| place | Jagsthausen |

| Geographical location | 49 ° 18 ′ 39.4 " N , 9 ° 28 ′ 9" E |

| height | 215 m above sea level NHN |

| Previous | Osterburken Castle (north) |

| Subsequently | Sindringen small fort (south) |

The castle Jagsthausen was a Roman military camp that close to the Upper Germanic Limes , a World Heritage Site was built and now built over in the area of the village Jagsthausen in the district of Heilbronn in Baden-Wuerttemberg is. Some Jagsthausen finds, especially the numerous stone monuments, are important for dating the entire Limes history.

location

The fortification, which was built in a wide flood plain, lies on the eastern edge of a sliding slope that gently descends towards the Jagst . To the south of the system, the river coming from the north makes an almost right-angled bend to the west. On the opposite bank, the slopes rise significantly upwards. The Limes border system, which runs straight north-south, is only around 400 meters away from the fort. The fort site was well suited to monitor the section of the border between Jagst and Kocher . Both rivers formed natural channels of incursion into Roman territory. An important area of responsibility for the troops was certainly also the observation of the high road , which runs along the ridge between Kocher and Jagst.

Research history

The first reports of excavations can be found in the second half of the 18th century and have been handed down in both of his works by the archaeologically savvy scholar Christian Ernst Hanßelmann (1699–1776). The oldest description is his discovery report from 1766, which was made in a "Roman laconium". This place probably meant the small fort bath. Early research work was carried out in the 19th century by Joachim Fest, who brought together many valuable pieces from Jagsthausen's early history. You are now in the museum of Jagsthausen Castle . In 1886 the small bathroom was rediscovered. In 1892 and 1906 the Reichs-Limeskommission (RLK) cut the defensive walls, which were already partially built over, with a few probes in order to be able to get a rough idea of the complex. From 1908 to 1913 finds were made in the western cremation cemetery, which can also be seen in the castle museum. Other smaller excavations were carried out through initiatives in the 1920s, 1930s and 1960s. It was not until 1984 that scheduled archaeological work was carried out by the Baden-Württemberg State Monuments Office , which brought significant new knowledge. The considerable Roman collections of the local historian Friedrich Krapf are also exhibited in Jagsthausen. You are in the Friedrich Krapf Museum , which is housed in the Old Town Hall.

In 1995, an open-air museum with a lapidarium made from casts of important Jagsthausen findings was opened on the area of the large baths, which are now an archaeological reserve . An initial exploration of sections of the largely built-up fort area with methods of geomagnetics, geoelectrics and ground penetrating radar took place in 1996.

Building history

Enclosure

Only a few remains of the around 185 × 152 meters (= around 2.9 hectares) large fort have so far been documented. The south gate of the camp, identified by the RLK as the Porta principalis dextera, was excavated . In addition, three intermediate towers were found on the north side: two (tower A, B) in the area of the praetentura (front bearing) between the Porta principalis sinistra (north gate) and the north-eastern corner tower and a third (tower C) in the rear area of the retentura (rear bearing ) between the north gate and the north-western corner tower. The archaeologists of the RLK suspected a fourth intermediate tower due to the location of tower C, which would then have been flanked by tower C and the north-west corner tower. The geomagnetic inspections carried out in 1996 on an 80-meter-long section of the northern fort wall in the area of the Retentura confirmed the more than 100-year-old research findings with Tower C. In addition, no clear new findings could be obtained. This also applies to the disturbed area in which the fourth tower was suspected. The areas examined in the area of the green spaces in front of Jagsthausen Castle are also not clearly recognizable with geophysical means. The floor plan, which can still be reconstructed today, shows that the Praetorial Front , the side of the garrison facing the enemy, which also pointed to the Limes about 400 meters away, was located directly in front of the terrain sloping steeply towards the Jagst.

Interior development

From the interior development, to the south of the Principia , the staff building, wall sections of unknown function have been cut, some of which are overlaid by the church. There were suspicions that these walls were connected to the commandant's apartment (praetorium) . The Praetorial Front, the side of the facility facing the enemy, was perhaps, as the RLK assumed, in the northeast and would then have been oriented towards the border installations. However, this is not certain.

Important find

A fragment of an inscription, which was discovered near the only partially known Principia , the staff building, and which was attached to a narrow stone, perhaps an altar, dates from the reign of Emperor Antoninus Pius (138–161). This document is the oldest dated find so far on the "Vorderen Limes" between Main and Rems . In connection with an analysis of inscriptions, the ancient historian Géza Alföldy speculated that this new Limes route was expanded “by 155” under the governor Gaius Popilius Carus Pedo (around 152–155).

In the area of the moat, the finger of a large bronze was recovered, which is dated between 150 and 250 AD.

Building inscriptions

A building inscription carved in sandstone from around 205 was found in the large bathroom. The name of Publius Septimius Geta (189–211) was subsequently deleted after his murder at the instigation of his brother, co-emperor Caracalla .

- Impp (eratoribus) L (ucio) Septimio Severo Pio

- Pertinaci et M (arco) Aur (elio) Antoni-

- no Aug [[g (ustis) et Geta (e) Caes (ari)]]

- balneum coh (ortis) I Ger (manorum)

- vetustate dilabsum a solo

- restitutum ex precepto

- Caesoni Rufiniani leg (ati) Augg (ustorum)

- pr (o) pr (aetore) cura agent Iulio

- Clodiano trib (uno) coh (ortis) s (upra) s (criptae)

Translation: “To the emperors Lucius Septimius Severus Pius Pertinax and Marcus Aurelius Antoninus, the Augusti, and the Caesar Geta. The bath of the 1st cohort of the Teutons, which was dilapidated due to its age, has been completely renovated on the orders of Caesonius Rufinianus, governor [of Upper Germany]. Iulius Clodianus, the tribune of the above-mentioned cohort, was responsible for the building supervision. "

This inscription is now in the Central Fund Archive of the Archaeological State Museum Baden-Württemberg in Rastatt . She names Caesonius Rufinianus as the governor at the time, who is already known through several inscriptions and who started his service in the Roman province of Germania superior (Upper Germany) shortly after the year 200 .

As early as the 18th century, a building inscription was found in the small fort bath in the Steinäcker corridor , which is one of the youngest inscriptions on the “Front Limes” and was created between 244 and 247. As usual, the inscription also names the two emperors ruling at the time, Philippus Arabs (244–249) and his son Philippus Caesar (247–249). However, their names were subsequently removed from the inscription, as they fell to the Damnatio memoriae .

- Impp (eratores) Caess (ares) [[M (arcus) Iul (ius) Ph [i] lip-]]

- [[pus]] P (ius) F (elix) Invict (us) Aug (ustus) [[[et M (arcus) Iul (ius)]

- [Ph [i] lippu [s] n (obilissimus) Caes (ar)]] '' balineum

- coh (ortis) I Germ (anorum) [[P [h] i [lippian (ae)]]]

- vetustate conlabsum re-

- stituerunt curante Q (uinto)

- Caec (ilio) Pudente v (iro) c (larissimo) leg (ato) Augg (ustorum)

- pr (o) pr (aetore) insistent Q (uinto) Mamil (io)

- Honorato trib (uno) coh (ortis) s (upra) s (criptae)

Translation: “The emperors Marcus Iulius Philippus Pius Felix Invictus Augustus and Marcus Iulius Philippus, the noblest Caesar, restored the bath of the 1st cohort of the Teutons, which was dilapidated due to its age, under the supervision of Quintus Caecilius Pudens, senator, governor of the Emperor, at the instigation of Quintus Mamilius Honoratus, tribune of the above-mentioned cohort. "

In later times, stone robberies, certainly also for the construction of the later Jagsthausen Castle, contributed to the extensive destruction of the fort and vicus . The red lock , which is certainly on parts of the praetorium , does not make investigations any easier.

Cohors I Germanorum (equitata) civium Romanorum

The only right from the start stationed in Jagsthausen force is the province most likely superior Germania excavated Cohors I Germanorum been. It is attested in many ways. Before the unit was moved to Jagsthausen around 159, it may be proven in the Wimpfen fort in the valley on the Neckar-Odenwald-Limes . The tradition for this unit is not without problems there.

On a Jagsthausen inscription dated between 222 and 235, the Cohors I Germanorum is mentioned with the nickname A [le] xa [n (drianae)] .

It is not certain whether the Cohors I Germanorum was actually a partially mounted unit, but there is strong evidence of this. As an important counter-argument it was asserted that if the unit had been a partially mounted Cohors equitata , according to today's knowledge, it would have had to be led by a prefect .

The 2nd century in the province of Moesia Inferior (Lower Moesia) as an occupying the fort Capidava on Romanian soil today detectable Cohors I Germanorum civium Romanorum is certainly different from the Jagsthausen unit because it there probably until after 167/168 from a department of the Legio I Italica has been replaced.

The troops were supplied at this location on the river route via Jagst and Kocher.

The Legio XXII Primigenia (22nd Legion "the firstborn" ) located in Mogontiacum (Mainz) is evidenced by several brick stamps from the small fort bath in Jagsthausen.

Officers and military personnel

At least four officers of the 1st German cohort from their time in Jagsthausen are known by name. A border guard commander of the cohort, Iulius Clodianus, is named as Tribunus cohortis in the building inscription from 198/209. Science knows the Tribunus cohortis Q. Mamilius Honoratus as another commander through the building inscription in the small fort bath that was created in 244/247 . Its direct successor was most likely the Tribunus cohortis Valerius Valerianus, who had a consecration stone set up in the newly renovated small bathhouse in 248 AD, dedicated to the goddess Fortuna balnearis , who in a thermal bath always in her role as protector of bathers and their health was seen, was judged (see also below).

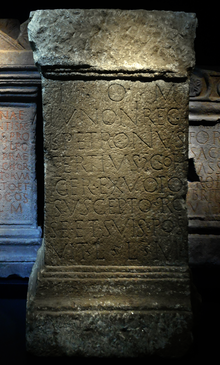

The name of a Centurio cohortis I Germanorum , Lucius Petronius Tertius, was found on a sandstone altar for Jupiter and Juno that can no longer be precisely dated and is now in the Limes Museum in Aalen . This consecration stone was found in the neighboring village of Olnhausen to the west . Perhaps, like others, he was abducted from the fort village of Jagsthausen in post-Roman times. On the tombstone of a family in Lyon (Lugdunum ) who emigrated from Lower Germany ( Germania inferior ) to Gaul ( Gallia ) from the end of the 2nd or the beginning of the 3rd century, another centurion of the Jagsthausen troop may be named, but it is there in connection with brought to the province of Germania inferior .

- D (is) M (anibus)

- L (uci) Sept (imi) Peregrini

- Adelfi Traianens [is]

- Oclatia Alexan [dra

- uxsor et L (ucius) Sept (imius) [Ale] -

- xander filiu [s et]

- Secundinia [Iusta ma] -

- ter misera [post amis] -

- sam fili (i) dulcissimi pie-

- tate et M (arcus) Valer (ius) Sil-

- vanus (centurio) coh (ortis) I Ger-

- manicae [in] Ger (mania) inf (eriore)

- consobrin [us p] aren-

- tes parenti [---]

- p (onendum) c (uraverunt) et su [b asc (ia) dedic (averunt)]

Translation: “The gods of the dead of Lucius Septimius Peregrinus Adelfus from Xanten ( Colonia Ulpia Traiana ). Oclatia Alexandra, the wife, out of love after the loss of the dearest son, and Marcus Valerius Silvanus, centurion of the 1st Germanic cohort in Lower Germany, the cousin (on the mother's side), the relatives had the relatives (the stone) set and consecrated under the ax . "

The formula sub ascia dedicaverunt , which occurs on many Gallo-Roman gravestones, is still unclear today. It has already been discussed whether the named centurion had even come to the funeral of his cousin or whether he was not named on the tombstone from his location by silent or written consent.

Commanders of the Cohors I Germanorum civium Romanorum

| Surname | rank | Time position | comment |

| Lucius Petronius Tertius | Centurio cohortis | ? | |

| Marcus Valerius Silvanus (?) | Centurio cohortis | End of 2nd / beginning of 3rd century | His sister Oclatia Alexandra moved with her husband Lucius Septimius Peregrinus Adelfus from Xanten to Lyon. |

| Iulius Clodianus | Tribunus cohortis | 198/209 | |

| Quintus Mamilius Honoratus | Tribunus cohortis | 244/247 | |

| Valerius Valerianus | Tribunus cohortis | 248 | After a happy return home, he donated a Fortuna altar in the small bath of Jagsthausen in 248. Possibly he was - still in a different position - in the years around 242/244 with his cohort during the defensive battles in the course of the second great Alemannic invasion, because the troops received the honorary name "Philippiana" during this time (244 at the earliest). The consecration to the returning Fortuna could thus also refer to the healthy return from the fighting. Most likely, Valerius Valerianus took over the position of site commander in 247/248 directly from his predecessor Quintus Mamilius Honoratus. |

In addition to the officers, there is also a signifer (standard bearer), Junius Iuvenis, from Jagsthausen . He donated his stone to Jupiter , Juno and the half-brothers Mars and Hercules in AD 221.

Beneficiaries

Also from Olnhausen comes an altar for Jupiter , Juno and the genius loci , which Christian Ernst Hanßelmann (1699–1776) once described for the first time as a wall in the outside facade of the church there. It was not until 1905 that the stone, consecrated in AD 166, was rediscovered there. He names a non-commissioned officer entrusted with special tasks, the beneficiarius consularis Lucius Flavius Paternus , as the founder . The altar is now in the depot of the Archaeological State Museum Baden-Württemberg in Rastatt . A year later, in 167, the beneficiary Lucius Flavius Paternus also donated a stylistically related stone to the beneficiary station in the Stockstadt Castle . The beneficiarius consularis was the highest rank that a legionary soldier could achieve among the beneficiaries. These men obviously enjoyed the special trust of their superiors and often had to act independently. Another beneficiarius consularis , Lucius Pompeius Gratinus, was entrusted with beneficiary duties from Legio VIII Augusta (8th Legion "Augusta") stationed in Argentoratum (Strasbourg) . He consecrated a stone in Jagsthausen in 179. The stone of Lucius Pompeius Gratinus is similar in its design to the beneficiary inscriptions from Stockstadt.

Fort baths

Bigger bathroom

→ Main article: Römerbad Jagsthausen

So far, two baths - a larger and a smaller one - have been discovered in Jagsthausen. The same finding was made at the Osterburken fort . Both Jagsthausen baths were renovated by the on-site Cohors I Germanorum . The larger thermal bath, known since the 19th century but only exposed in 1992, is located on today's Friedrich-Krapf-Straße. It orientated itself exactly on the line of flight of the road coming out of the south gate of the fort. The facility was in good condition when it was partially uncovered and gives reason to hope that it will be largely undisturbed. The state of Baden-Württemberg anticipated a development and acquired the land, which will now be retained as an archaeological reserve for future researchers. The wall findings, which the archaeologists only probed on the surface, were filled in again and drawn as a true-to-scale model using ancient masonry technology at today's ground level. The large thermal baths of Jagsthausen belonged to the type of baths in a row and, as the brick stamp finds of the 22nd Roman legion Primigenia Pia Fidelis (LEG XXII P PF) , which was barracked in Mainz ( Mogontiacum ) at that time , suggested, around 160 AD Fort erected. It could be proven that these stamps had been made in Frankfurt-Nied during the period in question. A total of over 70 bricks with over 15 different stamps from the 22nd Legion were recovered. Shortly after 200, the renovation, documented by a building inscription (see above), took place. The previously known part of the large pool is 30 m long. The entrance area, still unknown, is possibly under today's main street. The excavators of the large thermal baths expect it to be used until the first half of the 3rd century.

Smaller bathroom

The 31 m × 15 m large, north-south facing row baths, also located to the south, was around 200 meters from the fort. Today it would be found south of Gartenstrasse on the old Steinäcker corridor . In the very well-preserved complex, the walls of which were preserved up to 1.5 meters high, the excavators found remains of the sandstone paving and the screed. In addition, they could see fragments of the colored plaster. Bricks found in the rubble were stamped by the 22nd Legion. Two almost identical reliefs of the goddess Fortuna with cornucopia and rudder, which were found in the rubble in 1887, were remarkable. In addition, the half-life-size torso of a female statue, two clasped hands and an inscription dedicated to Fortuna from 248 came to light:

- In h (onorem) d (omus) d (ivinae) deae

- Fortunae sa-

- nct (a) e balinea

- ri reduci Va-

- lerius valeri

- anus trib (unus) c-

- oh (ortis) I (G) ermano-

- rum Phil (i) ppian-

- ae votum pos-

- uit Impp (eratoribus) d (ominis)

- n (ostris) Philippis Aug (ustis)

- III et iterum

- co (n) s (ulibus) l (ibens) l (aetus) m (erito)

Translation: “In honor of the divine imperial house. The returning holy Fortuna, (protective goddess) of the bath, was erected by Valerius Valerianus, tribune of the 1st cohort of the Teutons, Philippiana '(this altar) according to his vow. To the Commander-in-Chief, our Lord, Philip Augustus III. consul for the second time. Gladly, happily and for a fee. "

The 1st Germanic cohort had proven itself particularly well under Philippus Arabs (244–249) - possibly in the defensive fight against the furious second great Alemannic invasion at the time - and was therefore given the honorary name "Philippiana". The successful homecoming, which Valerius Valerianus mentions on the Fortuna altar, should also be placed in this context.

In addition to these finds, the building inscription (see above) of the bath is important, which testifies to a renovation of the thermal baths in the years between 244 and 247. Shortly before that, there was a large Alemanni attack, which the archaeologist and numismatist Hans-Jörg Kellner described for the first time using found coins. For example, the youngest coin in the Gunzenhausen fort was an Antoninian from the year 242, and the final coin in the Kösching fort was set to the summer of 241. In 242/243, the Regensburg small fort Großprüfening and the extensive Roman settlement near Pocking in the Passau district and other places were overrun. In Pocking, the final layer of fire hid an Antoninian from 241/243 or 240, which had only been in circulation for a short time. In the Künzing fort , an ace from the years 243/244, almost brand new, was found near a weapons hoard.

Like the emperor Chiselling name apparent from the inscription, the bathroom was even after 249. Thus, the inscription is considered one of spätesten epigraphic evidence of military activity before Limes case . At the latest with the subsequent Alemanni attack around 259/260, the fort with the camp village and its baths were overrun and had to be abandoned.

Vicus and cremation burial grounds

Finds show that the inhabitants of the extensive camp village ( vicus ) , located east above the Jagst, but mainly south and southwest of the military camp, achieved a certain level of prosperity and in some cases probably lived from exports. Between 1963 and 1965 there was a large pottery with five ovens in the hallway in the long garden , which in antiquity was on the north-western edge of the vicus ; near the western artery of the fort. It turned out that their production went far beyond the local market. Vessel shapes and mortars with a vertical rim were also found, as well as other objects that were no longer found in this form anywhere in the Limes and that suggest trade links to the north. The terra sigillata and the extremely high quality bronze miniature sculpture of Hercules , which was probably made in Italy and a replica of a work by the Greek artist Lysippos from the 4th century BC , also indicate prosperity . Is. In addition to water pipes and glass, the discovery of the upper part of a giant Jupiter column from the vicus is worth mentioning . An excavation carried out in 1984 (210 square meters) by the State Monuments Office (LDA) in the West Vicus showed the strip houses known from other fort sites on elongated plots of land facing the gable towards the arterial road. The archaeologists encountered a multi-phase development with earth and stone cellars. In a large-scale vicus investigation conducted by the same authority from 1987 to 1989 (around 3000 square meters) on the main street, some excellent, almost 1.5-meter-high basement rooms were found, some of which were furnished with carefully bricked wall niches . The residential development above consisted of half-timbered and stone buildings. Further excavations by the LDA in 1991/1992 and 1995 were dedicated to the southern camp village (around 1700 square meters). Half-timbered buildings, two stone cellars and an earth cellar could also be examined here. (see above). The archaeological work to date has shown that in addition to the strip houses typical of the Limes in Jagsthausen, urban forms with large stone buildings emerged early on, many of which had a comparatively elaborate floor plan.

Graves were discovered near the large thermal baths on the southeast edge of the camp village; also to the west in the direction of the escape route of the road leading out of the camp. Between 1908 and 1913 around 200 urn burials were found there. In addition, the remains of four tower-like tombs were found there, which also give insights into the life of wealthy residents in the border area. A third burial ground was located directly in the area of the vicus on today's Sennenfelder Straße, which bypasses the ancient fort square in a large arch that turns west.

Monument protection

The Jagsthausen Fort and the aforementioned ground monuments have been part of the UNESCO World Heritage as a section of the Upper Germanic-Rhaetian Limes since 2005 . In addition, the facilities are cultural monuments according to the Monument Protection Act of the State of Baden-Württemberg (DSchG) . Investigations and targeted collection of finds are subject to approval, and accidental finds are reported to the monument authorities.

See also

literature

- Dietwulf Baatz : The Roman Limes. Archaeological excursions between the Rhine and the Danube . 4th edition, Mann, Berlin 2000, ISBN 3-7861-2347-0 , p. 234 f.

- Rüdiger Krause : Archaeological research in Jagsthausen. New excavations in the Roman camp village. A preliminary report of the excavations from 1987-1989 . In: Württembergisch Franken 75 . Historical Association for Württembergisch Franconia, Schwäbisch Hall 1991, pp. 23–48.

- Willi Beck and Dieter Planck : The Limes in Southwest Germany . 2nd edition, Theiss, Stuttgart 1980, ISBN 3-8062-0242-7 .

- Hartmut Kaiser: Jagsthausen. Cohort fort . In: Philipp Filtzinger , Dieter Planck and Bernhard Cämmerer (eds.): The Romans in Baden-Württemberg . 3. Edition. Theiss, Stuttgart 1986, ISBN 3-8062-0287-7 , pp. 351ff.

- Klaus Kortüm : An archaeological discovery in the fort vicus of Jagsthausen . In: Find reports from Baden-Württemberg , Volume 13, Stuttgart 1988, pp. 325–349.

- Adolf Mettler in the series Der Upper Germanic-Raetian Limes of the Roemerreiches (eds. Ernst Fabricius , Felix Hettner , Oscar von Sarwey ): Department B, Volume 4, Fort No. 41 (1909).

- Andreas Thiel : Jagsthausen. Cohort fort, civil settlement, burial ground. In: Dieter Planck (Ed.): The Romans in Baden-Württemberg . Theiss, Stuttgart 2005, ISBN 3-8062-1555-3 , pp. 138ff.

- Andreas Thiel: Further archaeological discoveries in the fort vicus of Jagsthausen, Heilbronn district. In: Archaeological excavations in Baden-Württemberg , 1997 (1998), pp. 109–111.

- Andreas Thiel: The Jagsthausen fort bath - an example of the archaeological preservation of monuments in the 1990s. In: Preservation of monuments in Baden-Württemberg. News sheet of the Landesdenkmalamtes 25, (1996), No. 4, pp. 244-250.

- Andreas Thiel: A newly found renovation inscription from the second Roman military bath of Jagsthausen, Heilbronn district. In: Find reports from Baden-Württemberg , Volume 20, Stuttgart 1995, pp. 725-735.

- Andreas Thiel: The Roman Jagsthausen. Fort, vicus and settlement areas in the surrounding area . (= Material booklets for archeology in Baden-Württemberg 72), Theiss, Stuttgart 2005, ISBN 3-8062-2001-8 .

- Andreas Thiel: Complex strip houses on the outskirts. New insights into the planning and expansion of the Jagsthausen fort vicus . In: Peter Henrich (Ed.): The Limes from the Lower Rhine to the Danube. 6th colloquium of the German Limes Commission . (= Contributions to the Limes 6 World Heritage Site ) Theiss, Stuttgart 2012, ISBN 978-3-8062-2466-5 , pp. 89-97.

Web links

- Jagsthausen Fort on the website of the German Limes Commission

- Jagsthausen Fort on the private Limes project site of Claus te Vehne

Remarks

- ^ Klaus Kortüm : An archaeological record in the fort vicus of Jagsthausen . In: Find reports from Baden-Württemberg , Volume 13, Stuttgart 1988, pp. 325–349; here: p. 325.

- ^ A b Claus-Michael Hüssen : The Roman settlement in the area around Heilbronn . Theiss, Stuttgart 2000, ISBN 3-8062-1493-X , p. 51.

- ^ Britta Rabold, Egon Schallmayer , Andreas Thiel : Der Limes . Theiss, Stuttgart 2000, ISBN 3-8062-1461-1 , p. 82.

- ^ Harald von der Osten-Woldenburg: forts and Limes sections. An overview of geophysical surveys carried out in Baden-Württemberg so far. In: Jürgen Obmann: Limes Development Plan Baden-Württemberg . State Office for Monument Preservation in the Stuttgart Regional Council (ed.), Esslingen 2007. P. 40 f.

- ^ Harald von der Osten-Woldenburg: forts and Limes sections. An overview of geophysical surveys carried out in Baden-Württemberg so far . In: Jürgen Obmann: Limes Development Plan Baden-Württemberg . State Office for Monument Preservation in the Stuttgart Regional Council (Ed.), Esslingen 2007. p. 41

- ^ Andreas Thiel: A newly found renovation inscription from the second Roman military bath of Jagsthausen, Heilbronn district. In: Find reports from Baden-Württemberg , Volume 20, Stuttgart 1995, pp. 725–735; here: p. 726.

- ↑ CIL 13, 06561

- ^ Dieter Planck : Archeology in Württemberg. Results and perspectives of archaeological research from the Paleolithic to modern times . Theiss, Stuttgart 1988, ISBN 3-8062-0542-6 , p. 267.

- ↑ Martin Kemkes : The image of the emperor on the border - A new large bronze fragment from the Raetian Limes . In: Andreas Thiel (Ed.): Research on the function of the Limes , Volume 2. Theiss, Stuttgart 2007, ISBN 978-3-8062-2117-6 , p. 144.

- ↑ AE 1995, 1165 .

- ^ Andreas Thiel: A newly found renovation inscription from the second Roman military bath of Jagsthausen, Heilbronn district. In: Find reports from Baden-Württemberg , Volume 20, Stuttgart 1995, pp. 725–735; here: p. 730.

- ↑ CIL 13, 6562 ( figure ).

- ^ Dieter Planck, Willi Beck: The Limes in Southwest Germany . 2nd edition, Theiss, Stuttgart 1987, ISBN 3-8062-0496-9 , p. 60 (with ill.). The subsequent repayments are indicated by double square brackets.

- ↑ AE 1978, 0518 .

- ↑ AE 1994, 1306 .

- ↑ CIL 13, 06563 .

- ^ Andreas Thiel: A newly found renovation inscription from the second Roman military bath of Jagsthausen, Heilbronn district. In: Find reports from Baden-Württemberg , Volume 20, Stuttgart 1995, pp. 725–735; here: p. 734.

- ↑ Gabriella Bordenache: Romans in Romania . Römisch-Germanisches Museum, Cologne 1969, p. 48; Zaharia Covacef: Cohors I Germanorum a Capidava . In: Army and Urban Development in the Danubian Provinces of the Roman Empire . Alba Iulia, 2000, pp. 285-291.

- ↑ Martin Eckold: Shipping on small rivers in Central Europe in Roman times and the Middle Ages . Stalling, Oldenburg 1980, ISBN 3-7979-1535-7 , p. 18 f.

- ↑ a b CIL 13, 6552 .

- ↑ Another tribune, whose name has been lost, was possibly mentioned in the inscription CIL 13, 6553 , a dedication to the goddess Fortuna.

- ↑ CIL 13, 6555 .

- ↑ Claus-Michael Hüssen : The Roman settlement in the area around Heilbronn . Theiss, Stuttgart 2000, ISBN 3-806-21493-X . P. 71.

- ↑ CIL 13, 1892 .

- ↑ Gerold Walser: Roman inscription art. Roman inscriptions for academic teaching and as an introduction to Latin epigraphy . 2nd edition, Steiner, Stuttgart 1993, ISBN 3-515-06065-0 , p. 138.

- ↑ Lothar Wierschowski : Strangers in Gaul - "Gauls" in foreign countries. The epigraphically attested mobility in, from and to Gaul from the 1st to the 3rd century AD . Steiner, Stuttgart 2001, ISBN 3-515-07970-X . Pp. 312-313.

- ↑ CIL 13, 06556 .

- ↑ CIL 13, 06634

- ^ Joachim Ott: The Beneficiarier . Steiner, Stuttgart 1995, ISBN 3515066608 , p. 30.

- ↑ CIL 13, 6557 .

- ^ Andreas Thiel: A newly found renovation inscription from the second Roman military bath of Jagsthausen, Heilbronn district. In: Find reports from Baden-Württemberg , Volume 20, Stuttgart 1995, pp. 725–735; here: p. 731.

- ^ Britta Rabold, Egon Schallmayer, Andreas Thiel: Der Limes . Theiss, Stuttgart 2000, ISBN 3-8062-1461-1 , p. 84.

- ↑ a b c Claus-Michael Hüssen: The Roman settlement in the area around Heilbronn. Theiss, Stuttgart 2000, ISBN 3-8062-1493-X , p. 236.

- ^ Dietwulf Baatz: Roman roads in the Ries. In: Guide to the prehistoric monuments 41. Volume 2. Nördlingen, Bopfingen, Oettingen, Harburg . von Zabern, Mainz 1979, p. 264.

- ↑ Robert Roeren : On the archeology and history of Southwest Germany in the 3rd to 5th century AD In: Yearbook of the Roman-Germanic Central Museum Mainz . 7th year, Habelt, Bonn 1960, p. 217.

- ↑ Thomas Fischer, Michael Altjohann: The Roman Provinces. An introduction to their archeology . Theiss, Stuttgart 2001, ISBN 3-8062-1591-X , p. 132.

- ↑ Hans-Jörg Kellner: The Roman settlement near Pocking (Lower Bavaria) and its end. In: Bavarian History Leaves 25, (1960), pp. 132-164.

- ↑ Kurt Böhner : Guide to prehistoric and early historical monuments. Volume 24. Öhringen - Jagsthausen - Künzelsau - Langenburg. Verlag Philipp von Zabern, Mainz 1982, pp. 21/153.

- ^ Britta Rabold, Egon Schallmayer, Andreas Thiel: Der Limes . Theiss, Stuttgart 2000, ISBN 3-8062-1461-1 , p. 83.