Osterburken Castle

| Osterburken Castle | |

|---|---|

| limes | ORL 40 ( RLK ) |

| Route (RLK) |

Upper German Limes Vorderer Limes, route 8 |

| Dating (occupancy) | a) Cohort fort: around 160 AD to 259/260 AD at the latest b) Numerus fort: between 185 and 192 AD and at the latest 259/260 AD. |

| Type | a) Cohort fort b) Double fort |

| unit |

Cohors III Aquitanorum equitata civium Romanorum and Numerus Brittonum Elantiensium ? |

| size | a) Cohort fort: 186 × 115 m (= 2.14 ha) b) Annex fort (1.35 ha) |

| Construction | stone |

| State of preservation | Main fort not visible except for the SE defensive wall; Defense of the annex fort largely preserved; Numerusbad largely secured under a protective structure; Foundations of the cohort bath traced in the pavement |

| place | Osterburken |

| Geographical location | 49 ° 25 '36.2 " N , 9 ° 25' 28.4" E |

| height | 275 m above sea level NHN |

| Previous | Small fort Rinschheim (north) |

| Subsequently | Jagsthausen Fort (south) |

The Osterburken fort was a Roman military camp , the crew of which was responsible for security and surveillance tasks on the so-called "Front Limes" of the Upper Germanic-Rhaetian Limes . The UNESCO World Heritage site is located around 455 meters west of the Limestrasse on the southern slope of the Kirnautal in the Hager Flur. The still partially visible and preserved building remains are in the Neckar-Odenwald belonging Baden-Wuerttemberg City Osterburken in the Federal Republic of Germany . In addition to the fort, which later became a double fort, the buildings, some of which are easy to date, and valuable finds from the area of the extensive Roman camp village (vicus) have become known nationwide. Osterburken is one of the most important archaeological reference points on this Limes section.

location

The area, located in a gently rolling hilly landscape, was settled in prehistoric times. During the excavations in 1867, a Bronze Age hoard came to light in the fort area . The Roman surveyors built the cohort fort in the narrow valley floor of Kirnau, which flows from northeast to southwest, a location that was sometimes very humid and at risk of flooding in ancient times , the soils of which are characterized by limestone marls .

The view of the soldiers on duty in this garrison was severely limited by the ascending slopes in the north and south. In a north-easterly direction, however, the Limes, which cut across the valley floor from the slopes, could be seen directly. In addition, there were two Limes watch towers (Wp 8/28 and Wp 8/29) on the northern and southern slopes, which could send signals if necessary. However, the southern flank of the valley, which rises above the camp site, remained problematic, from which potential opponents could easily have launched their attacks. In the eyes of the planners, the hydrological and military disadvantages of this foundation made up for the close proximity to the river. With its northwestern flank, the fortification lay around three meters above the valley floor directly on the river. In this way, the ship and road traffic passing the Roman border could be monitored seamlessly. Also at other fort sites - such as the small fort in Sindringen to the south - it can be observed how the more difficult to control river bank was preferred to the disadvantage of a better camp site. The archaeologist Dietwulf Baatz believed he could see the self-confidence of the Romans in the “carefree choice of place” , who obviously did not expect a case of defense in the area of Osterburken.

The annex fort, which was built later and had an irregular floor plan, bordered directly on the south-eastern defensive wall. The topographical location of this extension was also difficult to cope with, as the valley slope from the southeastern gate of the original garrison to the corresponding gate of the annex fort rises around 22 meters. The soldiers lying there on sloping ground had to reckon with slope water from time to time and accordingly had to ensure that drainage was operational and efficient at all times .

The effort with which the extension had to be built and maintained was possibly due to the clumsy choice of location for the older cohort fort. The strategists had meanwhile become well aware of the growing dangers on the Vorderen Limes , so with this annex they also secured the hillside of the fort, which had been threatened until then.

Research history

The name of the corridor Hager or Hagenacker indirectly refers to the fort square. The rubble walls of the ancient defensive wall were still clearly visible in the 19th century and the farmers threw Roman stones, which came out of the ground during plowing in the fort area, onto the walls, so that a hag - an enclosed area - indicated the camp site. The remains of a lime kiln, which the scholar Christian Ernst Hanßelmann (1699–1776) had already seen, stood at the fort . A big problem in Osterburken was the robbery that was raised in 1892 in the Boten building state . The stone robbery, which was part of the agenda, was also problematic at the time, and the substance of the forts suffered heavy losses.

As early as 1840, the ancient pioneer Karl Wilhelmi (1786–1857) reported on his extensive "excavations of Roman ruins" in the fort and in the camp village. He also stated that "a long time ago" Roman coins, objects and stone monuments from Osterburken had become known. He explicitly mentioned, among other things, an inscription from the Legio VIII Augusta , which "1717 or 1718" came to light while plowing. He was also aware of the discovery of the fort bath I, discovered in 1826. Further investigations on this bath took place partly in 1973 on behalf of the State Office for Monument Preservation under the direction of the archaeologist Rolf-Heiner Behrends and in 1983. Only major new construction measures at the site made it possible to carry out a comprehensive excavation and reassessment in 2004 and 2005. The archaeologist Klaus Kortüm was in charge of these investigations .

In 1861 the famous Mithras relief was discovered on the right bank of the Kirnau on Bofsheimer Strasse , a copy of which is now in the Roman Museum in Osterburken.

The excavations of the Mannheimer Altertumsverein in 1867 proved the existence of a double camp for the first time. In 1892 the Reichs-Limeskommission (RLK) under the direction of the route commissioner Karl Schumacher (1860–1934) began its extensive investigations in both fort areas and completed them in 1893. Today's Hagerstraße traces the course of the Roman camp road from the north gate (Porta praetoria) to the south gate (Porta decumana) on the area of the cohort fort . It was also Schumacher who discovered a Roman burial ground for members of the military and civilians northeast of the fort. Just a little further today, the Bofsheimer Strasse crosses the Limes. After the more recent excavations in 1964, 1972 and between 1977 and 1979, the archaeologists examined over 100 cremation graves. With the approval of the Grand Duke, the annex fort could be preserved in the 19th century, while the actual camp was released for building over without major excavations. After the unfortunate maintenance measures on the annex, Schumacher demonstrated a number of errors to those responsible. In 1991 as well as in summer 1992 excavations took place at the fort, whereby the defensive trench between the cohort fort and the annex and the eastern wall of the annex fort in the area of this trench were examined.

In 1976, Bad II was found northeast of the fort in the valley floor . The remains of the building were largely uncovered between 1976 and 1980. Based on the valuable findings, the citizens of Osterburken founded the Historisch Verein Bauland to secure the preservation of the pool. After negotiations with the city of Osterburken, the city administration decided to keep the bath under a shelter and to combine it with the Römermuseum Osterburken, which was planned at the same time .

During civil engineering work during the pillar foundation for today's beneficiary bridge, a hitherto unique sanctuary for local beneficiaries was uncovered. The emergency excavations started by the archaeologist Egon Schallmayer were continued under his direction in 1983, 1984 and 1986. The discovery of this ensemble made an expansion of the Museum at Bad II, which was also inaugurated towards the end of 1983, inevitable. In 1986 the extended museum building opened its doors. Another reopening took place in 2006 after a new museum wing was opened over parts of the cohort baths discovered by Wilhelmi. The foundations of this bath in the outside area were visibly traced in the museum forecourt (Römerplatz) and in the adjacent pavement of today's Römerstraße. In autumn 2014, the museum director and archaeologist Jörg Scheuerbrandt had a reversible metal frame erected in the form of a Roman camp gate on the fort grounds, which is intended to give visitors an impression of the height and outline of such a structure.

For the post-Roman development of Osterburken, the prehistorian and medieval archaeologist Joachim Henning made an important contribution in 1985, in which he was able to re-date a hoard found from the fort moat that was considered to be Roman times .

Building history

Cohort fort

Dating approach

Apart from the archaeological excavation results, there is so far no direct ancient written evidence of the construction of the Vorderen Limes . The ancient historian Géza Alföldy (1935–2011) speculated after evaluating two inscriptions found in the Mediterranean that the Limes stretch of the Front Limes had been expanded “around 155” under the Upper Germanic governor Gaius Popilius Carus Pedo (around 152–155). At least important military activities or troop movements must have taken place. The scientist placed himself in the tradition of the archeology pioneer Ernst Fabricius (1857–1942), who had already determined this period in 1902.

Newer finds and methods could possibly frame this assumption more precisely or correct it in terms of time. The felling date of the winter 159/160 AD could be determined on the earliest dendrochronologically analyzable timber from the beneficiary consecration district. However, under the temple there was a stone spring with a nymph and dedicatory inscription, which was stratigraphically undoubtedly older. The inscription was left by Iulius Adna [matius?], A Decurio (Rittmeister), who possibly belonged to the Cohors III Aquitanorum equitata civium Romanorum (3rd partially mounted cohort of Aquitaine Roman citizenship), which was later found in Osterburken . Only when the beneficiaries were sent to Osterburken was the place at the Nymphaeum subsequently inscribed exclusively by this unit. Alföldy's research suggests that the construction of the spring catchment could have occurred during the governorship of Gaius Popilius Carus Pedo.

The cohort bath investigated from 2004 onwards offered further datable material. It was examined by the laboratory for dendrochronology at the Hemmenhofen office of the State Office for Monument Preservation Baden-Württemberg. It should be noted that the mighty load-bearing oak posts from the first construction phase, preserved in the groundwater, were felled in the late year of 164 AD. According to Kortüms, further Osterburkener woods could be dated to the year 161 AD, which supports considerations that the actual Front Limes was only with the Rhaetian Limes - from which the matching dates come - in a cross-provincial expansion shortly after the death of Emperor Antoninus Pius (January 161). An important basis for this thesis is the consideration that the construction of the cohort bath of Osterburken in all probability took place not insignificantly later than the construction of the fort. According to Kortüm, a significant presence of Roman troops before AD 160 is becoming increasingly unlikely. The reassessment of the consecration stones of the centurion Veranius Saturninus , who still had the Numerusbad of Neckarburken rebuilt and enlarged by his unit, the Barracked Numerus Brittonum Elantiensium (unit of the Elzbrittons) in 158 AD , suggests a move around 160 AD . Chr. think. The centurion also left a consecration stone at his new garrison town of Osterburken - albeit without a date. His troops are regarded by research as the number for which the annex fort of Osterburken, built sometime between 185 and 192 AD, was most likely built. This conjecture is underlined not only by the documented presence of Veranius Saturninus, but also by the presence of the 3rd Aquitaine cohort, who had already been in Neckarburken together with the Elzbrittons. Thus, both units would have come back to a common garrison location in Osterburken - somewhat delayed.

The thesis of a later dating approach of the Vorderen Limes raises new questions. The date around 160 AD not only makes the Osterburken nymphaeum, which is older in time, more puzzling. There were some older Roman pits under the cohort bath that had nothing to do with the construction of the thermal baths. The archaeologists recovered organic remains, roots, wood waste and some processed wood here. Small amounts of Roman pottery were also found. The evaluation of these finds is still pending. In this context, emphasis should also be placed on the wood samples dendrochronologically examined by the forest scientist Bernd Becker (1940–1994) from a well dug directly in the Murrhardt Fort that was built around 159 AD . There is also the oldest datable fragment of inscriptions from the "Vorderen Limes" from the reign of Emperor Antoninus Pius from the Jagsthausen Fort to the south , which requires an assignment. Only new discoveries and analyzes may make a final assessment of the events at that time possible.

Enclosure

A previous, older wood-earth store, as could be proven for example at the Murrhardt fort , has not yet been found in Osterburken. The oblong, rectangular stone fort in the Kirnau valley, around 500 meters away from the Limes, was 186 × 115 meters (= 2.14 hectares) and was occupied by the Cohors III Aquitanorum equitata when the Dekumatland was extended to the Front Limes by moving the Roman Empire forward . The spring version with the inscription of a squadron leader, which was subsequently built over at the beneficiary consecration district with wood felled in the winter of 159/160 AD, indicates the latest point in time that documents the presence of the cohort. It is therefore assumed that the Roman military was employed in Osterburken a few years before this terminus ante quem .

The ground plan was based on the course of the river with its flanks and, with its praetorial front in the northeast, on a stream flowing past there, which flowed down into the Kirnau through a deeply cutting, small valley oriented to the northwest. The construction scheme follows the typical mid-imperial structure (playing card shape), which provided for a gate on each of the long and broad sides. In each of the rounded corners of the fort wall stood a watchtower, the rounded outer front of which protruded slightly from the defensive wall. With the exception of the one-lane Porta decumana , the rear, northwestern passage, the gates were possibly two-lane. They each had two gate towers flanking them. A total of four intermediate towers - two on each long side - were found in the area of the Latera Praetorii , the central part of the camp, and the retentura (rear camp ). At least some of the towers were built in multiple phases. The building material for the defensive wall consisted of limestone. The plaster residue found on it still had grout lines.

The fortification probably only had a circumferential pointed ditch, which was measured on the northeast side in front of the defensive wall with a width of 7 meters and a depth of 2 meters. It was found that this trench cut through the area in front of the gate there, the Porta principalis dextra , with a berm of 2.5 meters in this area . Therefore the fort could only be reached at this point with the help of a wooden bridge. At the 8.3 meter wide main gate, the northeastern Porta praetoria , the eastern of the - possibly - two passages had been walled up later. The purpose of this measure can no longer be understood today, but similar findings have also been made at other Limes forts. For example at the Rhaetian fort Pfünz . On the inside of the south-eastern gate tower of the Porta praetoria in Osterburken, a stone was walled up, which was found in 1892. It shows a small building inscription from the centurion of Primius Montanus of the 22nd Legion. Apparently the unit had been building the camp. However, the stone cannot be dated any closer. The same difficulties of assignment exist with a badly damaged building inscription of the Cohors III Aquitanorum equitata . There it is mentioned that the troops restored or rebuilt an unknown building.

Interior development

The interior of the fort has only been examined in small sections. During the excavations in the 38.5 × 45.8 meter Principia (staff building) , the largest building erected in the middle of the fort, the main focus was on the flag sanctuary, as the richest finds were believed to be there. As usual, the sanctuary was built in the center of the rear wing of the staff building and protruded from the rear facade of the building with its rectangular, solidly bricked apse . The interior of the apse was rounded in a U-shape. In the praetentura (front camp ) of the garrison, foundations were observed to the northwest, between which grains of grain were found. A storage facility (Horreum) could have stood here.

- Details at the cohort fort

Annex fort (numerus fort)

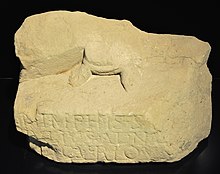

The extension, the annex fort on the right flank of the cohort fort, was built during the reign of Emperor Commodus (180-192) and was built by the Legio VIII Augusta in Argentoratum ( Strasbourg ) . According to archaeologist Felix Hettner (1851–1902), four (sic!) Building inscriptions testify to this . Schumacher, who had carried out the most extensive investigations in Osterburken at the time, only knew three similar or identical inscriptions, the oldest, which was found in the 18th century and then lost, was probably also found in the area of the annex. The other two were found during the restoration and excavation of the Annex-Spitz trench, one in autumn 1896 on the south corner, the other in March 1897 in front of the eastern corner tower.

The content of these inscriptions, created between AD 185 and 192, is the same - but at least very similar:

- Imp (eratore) Ca [es] ar [e M (arco) Aur (elio) Commodo]

- [Antonino Aug (usto) ---]

- leg (io) VIII A [ug (usta) p (ia)] f (idelis) c (onstans) [C (ommoda)]

- a [s (olo)] f (ecit)

Translation of the inscription recovered in 1897: "For Emperor Marcus Aurelius Commodus Antoninus Augustus ... the 8th Legion" Augusta ", the dutiful and faithful, steadfast and useful, built (the building) from scratch."

With the inscription plate there were still wedge-shaped stones, which probably came from one of the vaulted windows of the eastern corner tower. The plate had most likely been visibly bricked up on one wall of this tower. With the second inscription from the southern corner tower, the same vaulted stones made of sandstone and tuff were found again . Due to the stones that have been preserved in the Römermuseum Osterburken to this day, the upper width of the rising masonry of these towers can be determined.

The ground plan of the extension adapted to the site, which was probably intended for a numerus , most likely the Elzbrittonen from the Neckarburkener Ostkastell, has the shape of an irregular trapezoid and covers 1.35 hectares. Obviously, in addition to its function as a troop camp, the annex fort should also compensate for the strategic disadvantages of the cohort fort located deep in the valley. Because its south side reached up to the hillside and enabled additional visual connections to the Limes watchtowers. Because of the steeply sloping terrain, it was not possible to build as dense a building as was usually the case with the Roman garrison types. This topographical condition can also explain the large inner area of the facility, which is particularly large for a numerus fort. Almost no major excavations were carried out by the RLK within the fortification. Therefore, only a small, circular pit ( marked with a D in the RLK plan ) at the eastern end and individual smaller wall sections are known from this area .

The new defensive wall, which began behind the eastern and southern corner towers of the cohort fort, had a width of 2.30 to 2.40 meters in the area of the foundations, and its rising masonry was 1.60 meters. Behind the wall, the builders had poured an earth dam, which not only strengthened the stone wall, but also served as a battlement. This dam could be determined at one point with a width of seven meters. The three gate structures had a matching construction, each with a single passage between 3.22 and 3.62 meters wide and two gate towers. A detail that illuminates the range of structural variations within a province are the towers that protrude only a little from the surrounding wall. At many other garrison sites - such as the Niederbieber fort - the towers that protruded further out into the new buildings had already prevailed at this time. From there, in the event of an attack, the defenders were able to take their defensive walls under flanking fire and thus, among other things, prevent or at least make it more difficult to board the wall.

As can be seen on the landside flank of the cohort fort, the old moat remained there even after the new fortifications were built. The filling of this trench, which was examined in 1991 and had a maximum width of 10.5 meters, contained a final layer of fire and traces of battle from the years of the Limes fall in AD 259/260. In 1992, traces of a previous period of danger during the early 1930s were found. Century visible. At the bottom of the eastern defensive wall of the annex fort, which was placed in this older ditch when it was built, a hoard of a total of 327 mostly freshly minted silver coins was found 1.7 to 2.2 meters below the top of the wall. The youngest of the recovered coins were minted during the reign of Emperor Severus Alexander (222–235). The find made it clear that the old moat was no longer maintained at this point in time and must at least have been filled in places.

- Details at the annex fort

The oblong, rectangular southern corner tower with Opus spicatum, possibly built later

Troops and military personnel

Two troops can be located after Osterburken.

| Time position | Troop name | comment |

|---|---|---|

| around 160 - around 259/260 AD | Cohors III Aquitanorum equitata civium Romanorum | As military diplomas show, the cohort was always in the province of Upper Germany. The previously oldest known mention dates from May 21, 74 n. Chr. Other mentions were made in the years 82, 90, 116, 130 and on 16 October 134. Built-brick temple give an indication that the unit first in Fort Stockstadt located and her presence at this place can be expected during the reign of Emperor Trajan (98–117) before she was moved to the western fort in Neckarburken. The troops then built the Osterburken cohort fort in the course of moving the Limes forward and stayed there until the time of the Limes falls. The further fate of the 3rd Aquitaine cohort is unknown. |

| around 190 – around 259/260 AD | Numerus Brittonum Elantiensium | The origins of the number are unknown. The first inscription mentioned comes from Neckarburken. There it was close to the 3rd Aquitaine cohort in the east fort . A building inscription from the east gate, which can be dated between 145 and 161 AD, identifies them by name. During this time, the troops under the centurion Veranius Saturninus also rebuilt the associated fort bath in AD 158. The numerus fort in Osterburken, which the Legio VIII Augusta built “from scratch”, was built between 185 and 192 AD . It is possible that the troops belonging to this annex were not on site during the construction period. Then, according to the assumption of the scientists, the Elzbrittons took quarters there until the time of the Limes Falls. |

A dedicatory inscription to the goddess Minerva was recovered from the cohort fort, which the centurion Titus Attonius Fortio - a former Cornicularius - and the centurion Placidius Placidinus had erected. The names of the Centurion (Sil) vanus and that of the Decurios Iustius Attianus were also preserved through dedicatory inscriptions to the respective genii of their units.

In 1910, near the Porta decumana , there was another votive altar dated to a consulate from AD 198. The stone was set by ... pius Iulianus, military doctor of the 3rd Aquitaine cohort, in honor of his troops. A dedicatory inscription was discovered at the same gate in 1868, which once included the statuette of a genius. Its lower part was preserved at the altar-shaped base. The stone had been set up by the Optiones - a NCO level - of the 3rd Aquitaine cohort for the genius of their unit. The naming of the honorary name Philippiana , which the cohort carried under Emperor Philippus Arabs (244–249), limits the period of use to the years 244 to 249 AD. Another genius consecration for the troupe - at that time with the nickname Severiana - had already arisen under Emperor Severus Alexander (222-235). Secondly, a dedication to the genius of his tower (squadrons), which was discovered at the fort in 1892 and which had been set by the Decurio (Rittmeister) Iustius Attianus, was reused.

On a bronze Tessera militaris that has now disappeared , the non-resolvable abbreviation SVC and the origin of the piece by the centurion of Publius Paternus were found. Other bronze tesserae came from the Century of Messor Saciro and that of Titus Quartus Agraptus.

The only known up to now garrison commander (Praefectus cohortis) 3rd Aquitanierkohorte was from Rome originating knight Publius Allius Proculus, whose dedicatory inscription during the crash of 1971 neoclassical Osterburkener Kilianskirche found secondary walled up.

- Inscriptions of the Cohors III Aquitanorum equitata civium Romanorum

Fort baths

Bad I (cohort bath)

Two fort baths were discovered in the past 200 years. Wilhelmi was familiar with the location of the first known bathing facility of the former inn "Badischer Hof". While digging a well in the cellar vaults, a hypocaust with brick stamps from the Legio XXII Primigenia was found . The Augsburg Ordinaries Post newspaper from 2 August 1826 cites the Fund Date July 15, 1826 stated, among other things, that the side walls with "Gyps drowned and were colored like marble." In addition to the geziegelten bottom fell the excavators at that time the hollow wall tiles of the heating system and " very long iron nails ” . It was already recognized at that time that there was a Roman military bath here, which the 22nd Legion had built. Today the find is listed in the specialist literature as Bad I , which was located in the area of the theater at Römerstrasse 16, which was closed in 2002 and then demolished. This cinema was located in the former "Badischer Hof". As early as February 5 to 8, 1973, parts of the thermal baths were scientifically examined by Behrends during renovation work in the basement of the cinema in the course of an emergency excavation. The archaeologist reported difficulties with the high groundwater level, which reached the upper edge of the hypocaust pillars without constant pumping. Another room came to light in the early summer of 1983. The inscription Legio VIII was found in it .

Since the extensive excavations in 2004/2005 at the latest, it has been certain that Bad I, which is almost four times larger than the Numerusbad, was the central military bath on site and was probably built around 140 meters east of the Porta Praetoria of the cohort fort with the arrival of the Cohors III Aquitanorum . Despite massive disruptions from the medieval moat, the masonry had survived the millennia exceptionally well. The building, with its baths arranged one behind the other, belongs to the row type, in which the visitors could easily enter the cold, warm and hot water basins and tubs according to the prescribed procedure due to the standardization. The exact time can be obtained, among other things, with the help of the dendrochronologically usable wood recovered in 2004/2005 and a comparison of the brick stamps found. These belong to groups that were established during the construction phase of the Vorderen Limes . It is noteworthy that during the construction of the hypocaust in the tepidarium only bricks from the 22nd legion were used, while in the caldarium a stamped batch of the 8th legion was obviously used. Apparently both legions delivered material at the same time. As mentioned above, the felling date for the oldest wooden posts in the bathroom was the late year 164 AD. The timbers were probably installed a short time later.

The structurally multi-phase thermal bath was entered from the generously planned basilica thermarum in the north . This room was intended as a multi-purpose facility and initially existed as a wooden construction before it was rebuilt in stone in 190 AD, so that it can be dendrochronologically understood. Inside, both the roof of the presumed half-timbered hall and that of the stone building were always supported by wooden supports that were replaced once during the stone construction phase, possibly in the course of reducing the size of the vestibule, as can be seen so often during the 3rd century on the Limes. The reception, sports and changing areas were located in the Basilica thermarum . Then those seeking relaxation came to the cold bathing area ( frigidarium ) , on the west side of which there was a cold water tub (piscina) , the screed lining of which was completely renewed before those responsible probably had the pool reduced in size in the 3rd century. The sweat bath (sudatorium) was determined on the opposite side, which was set up in two elongated rectangular rooms connected one behind the other along the east side. The second room of the sudatorium could also be entered from the first leaf bath ( tepidarium ) , which was accessible through a narrow door let in on the south side of the cold bath. The first and smaller of the two lukewarm rooms had underfloor heating that rested on sawn limestone pillars. In contrast, the pillars of the second tepidarium were made of bricks, as was also observed elsewhere in the building. The rectangular niche on the east side of the second leaf bath may have been the location of a hot water tub in ancient times. In the adjoining hot bathing area ( caldarium ) to the south , which was the size of the second tepidarium , there was also a tub on the west side in a wall, which, according to archaeologists, was in use until the end of bathing. Accordingly, there was another tub on the south side of the hot bath. On the east side of the caldarium , a door led into an oblong, rectangular adjoining room, which was only constructed from half-timbered walls. Perhaps there was a massage room here or a possibility for shower rooms. During the reconstruction, also determinable in 190 AD, this room was demolished and the door walled up. In the course of this work, the construction crews also significantly increased the outside level in the rear area of the spa. The excavators were also able to identify other structural changes inside the complex. So there was work on the wall heating and floor screeds. The caldarium was heated by a wood-built boiler room (praefurnium) that was built behind the southern wall of the bathing building.

With numerous late limes time Sigillaten and a silver-plated Antoninian from the reign of Emperor Philip the Arab (244-249), the find material ends in time.

Bad II (number bath)

- Phase 1

During construction work in 1976, a second, smaller bath complex about 40 meters west of Bath I came to light, the remains of which, like those of the fort, are a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Numerous brick stamps from the thermal baths prove the presence of construction crews from Legio VIII Augusta . The brick stamps and the smaller size allowed the conclusion that the bath was built for the number of the Elzbrittons. According to this, the building would not have been built until between 185 and 192 AD, when the annex fort of the Elzbrittons, which can be dated with inscriptions in this time window, was built. The distance to the northeast gate of the cohort fort - the Porta praetoria - is around 100 meters. This system also belongs to the row type and consists of several rooms staggered one behind the other. The changing area ( apodyterium ) in the entrance area , which was entered from the north-west, could only be partially exposed. This is followed by the frigidarium , which includes a semicircular apse with a bathtub attached to the south wall. In the cold bath, a developed sewer also begins, which led to the outside under the changing room. To the north of the apodyterium and frigidarium there are two adjacent rooms that were heated from the northeast. Both rooms are addressed as a sudatorium and can be entered from both the changing room and the cold bath. To the east, the frigidarium was followed by a lukewarm area. Here, too, there is a rounded apse in the south, which, however, formed a structural unit with the actual room. The tepidarium had no tubs, but was used for massages and relaxation. After the tepidarium , the ancient visitor entered the first, smaller caldarium again in an easterly direction - a sweating room with a built-in hot bath. In order to be able to maintain the correct temperature, this area on the north wall behind the tub has its own boiler room. The last hot bathing area is again in the east. The larger caldarium is located here . In the south there is again a semicircular apse with a cold water tub and to the east a rectangular niche in which a hot water tub is built. Immediately to the north of this niche protruding from the bathroom wall is another boiler room.

- Phase II

During the first half of the 3rd century the bathing facility was reduced in size. It is not possible to provide more detailed information about the time, as the brick stamps that belonged to this phase and were found were only walled up secondary. This dismantling can also be observed at other fort sites for the crisis-ridden late period of the Upper Germanic-Rhaetian Limes up to its end in 259/260 AD. At Fort Walldürn to the north, an inadequate construction could be observed for the almost improvised dismantling of the new building, which was only inaugurated in August 232 AD. One reason for this last renovation is attributed to the incorrect building material used for the hypocaust pillars, which after a short time caused static problems. In the bath of Kastell Schirenhof , under a charred wooden floor of the final layer of fire, a coin from the year 228 AD was found. This is the term ante quem for the hasty and scaled-down reconstruction, which is also documented there. Since the archaeologists reckon with the destruction of the vicus and bath in Schirenhof during the first great Alemanni invasion in 233 AD and the Roman troops evacuated the garrison there shortly after 244/247 AD, the reduced bath there was not in the for very long Use and fell into disrepair. At Fort Buch, on the other hand, the downsizing was made after a suspected Germanic attack in early summer 254 AD, when the camp village was destroyed by a fire. In addition to the warlike influences or the withdrawal of troop contingents, there is also the assumption that the downsizing of baths was also due to economic reasons. Another cause could be ecological. The archaeologist Oscar Paret (1889–1972) said that the raw material wood, which was then massively required, had been overused in the vicinity of the cities and settlements and that the energy source for the thermal baths had to be brought in from far away.

The dismantling in Osterburken affected the easternmost wing of the Caldarium . This was given up together with the cold and hot bathtub and the praefurnium . Thus only the smaller sweat room was available to the bathers. The former passage to the abandoned bathing area was now walled up.

Since the largely heatable apsidal building of an unknown use in the immediate north-east is precisely aligned with the numerus bath, it was considered that it should be assigned to the same construction phase. Possibly there was also a use tailored to the bathroom.

- Numerus bath

Vicus

As an important place on the Limes, Osterburken had a large vicus with various sanctuaries. In addition to the beneficiary sanctuary, the well-preserved Mithras relief discovered in 1861 during excavation work for a cellar, which came out of the ground with two altar stones without inscriptions, testifies to this. There is a short inscription on the base of the relief itself, which gives information about the former - certainly wealthy - founder:

- D (eo) S (oli) i (nvicto) M (ithrae) Mercatorius Castr [e] nsis in suo const (ituit)

Translation: "Mercatorius Castrensis (this altarpiece) had the undefeated sun god Mithras erected on his property."

Civil settlement structures were found on the road in front of the Porta decumana of the cohort fort in the southwest, in front of the southeastern exit gate of the annex above the valley and - with the actual settlement core - northeast of the Porta Praetoria on the left and right side of the Kirnau. The road from the Porta praetoria led along the Kirnau to the Limes. In addition to the thermal baths used by the civilian population, other public facilities were also located there.

Burial ground

So far, only one cemetery north of the fort and vicus - on the opposite bank of the Kirnau - in the Affeldürn corridor was uncovered, which was built over after the excavations. The archaeologists opened up over a hundred burials there. In addition to the predominant cremation graves, only a few body graves were found, some of which were laid out for children. In addition, two horse burials were uncovered. The sometimes very rich grave inventories included oil lamps, bowls, plates and jugs as well as jewelry, glass vessels and coins. Remains of a larger tomb had already been found in the 19th century.

- Finds from the burial ground in Affeldürn

Fall and Post-Roman Development

The Münzhort , salvaged in 1992 from the ditch between the cohort and numerus fort , coincides with the severe attacks of the Germanic peoples in 233 AD (first Alemannic storm) when they overran the Upper Germanic-Rhaetian Limes on a broad front. In this context, for example, in addition to the large coin hoard from the Ober-Florstadt fort in Wetterau , the sinking of the Pfünz fort on the Rhaetian Limes in the Altmühltal is seen. The last known and datable consecration stone in the beneficiary sanctuary was erected in 238 AD. The latest datable inscription of the 3rd Aquitaine cohort from Osterburken comes from the reign of Emperor Philip Arabs (244–249; see above). As mentioned above, the final coin from the cohort bath was also minted during the reign of this emperor. At the latest with the fall of the Limes in 259/260 AD, the last Roman border posts on the Front Limes went under or were evacuated. Weapons and skeletal remains at the Osterburken fort point to a violent end in the middle of the 3rd century. Wilhelmi and his colleagues on the western edge of the numerus fort had already made the relevant findings for this finding. They found a skeleton with legs spread wide apart, with a crooked arrowhead attached to it. The second skeleton of a young adult, partially buried under the rubble of the fort wall, had one arm bent over his head while the other stretched away from him. On and in the vicinity of the dead lay rubble walls, Roman coins, belt fittings, a silver-plated bronze brooch , wide arrowheads, a small triangular bullet bolt and large charred wood. The two victims remained where they died. If, among other things, other swords, lance and arrowheads came to light during the conservation work in the trench of the annex in 1896/1897, skeletons of at least three adults from the youngest Roman stratum were recovered in the defensive trench between the cohort fort and the annex in 1991. In addition to animal bones and ceramics, the found material included a fragment of a helmet shell on which there were clear traces of the use of force. Among the dead lay rubble from the fallen fort wall and burned remains of the wooden interior buildings.

- North-eastern pointed ditch of the cohort fort

In some camp villages, however, it was possible to prove the presence of a small settlement community with reference to the Roman world beyond this difficult time until late antiquity, for example in the vicus of the Rhaetian fort Buch . In the volume of the Upper Germanic-Raetian Limes of the Roman Empire , published in 1897, Schumacher reports that most of the 200 Roman coins known from Osterburken at that time came from the fort area. One of these coins was assigned to the reign of Emperor Claudius Gothicus (268-270) and two more to the time of Emperor Constantius II (337-360). In addition to coins, fibulae also belong to the traces of settlement on the fort from the post-Limes period. Should settlement have been demolished in the second half of the 3rd or 4th century, the Hort of Osterburken , which was recovered from the moat of the fort in 1897, proves that either in the later 4th or early 5th century - after the Alemannic settlement of the room - people again lived and worked on the Kirnau. The hoard made of 53 iron objects, which in the specialist literature was partially located in Roman times until recently, contained, among other things, two long swords ( spathe ) that differed significantly from the Roman forms, six partially repaired scythes, drills and a saw, hicks and axes as well Cattle bells and a ploughshare. In addition, there were kettles, chains of fire and various other kitchen utensils, typical objects of the Germanic peasant society of the time during the migration period .

Chronology of the Roman Osterburken

The sources for all the data mentioned are named in the article and are no longer repeated in this section.

| Construction phase | Dating | event |

|---|---|---|

| Phase I. | 160/165 AD | Establishment of the beneficiary consecration district (after winter 159/160) and the cohort bath (after late year 164). The cohort fort for the 3rd Aquitaine cohort must have been built shortly before the establishment of the consecration district, under which there was a decurion consecration stone. At the same time, the Front Limes was built . A fragment of the inscription from the Jagsthausen fort in the south shows the establishment of the military facilities for the late reign of Emperor Antoninus Pius (138–161). |

| Phase II | 185 to 192 AD | Construction of the annex fort. The Elzbrittonen from Neckarburken are accepted as troops. |

| Phase III | 233 AD | First Alamannensturm: A coin hoard is buried in the abandoned fort ditch between the cohort and annex fort. |

| Phase IVa | 238 / 244–249 AD | The last datable use of the beneficiary sanctuary (238); last datable inscription of the 3rd Aquitaine cohort (244–249). |

| Phase IVb | between 249 and 259/260 AD at the latest | Destruction by fire, violent demise of the fort. |

Archaeobotanical studies

In 1982, when deep drilling for the pile foundation of a bridge over the Kirnau, the remains of a Roman consecration district of the beneficiaries were discovered in the immediate vicinity of the river, which was in continuous use during the Roman presence. The sanctuary, which was already repeatedly affected by floods in ancient times, was located under 3.50 meters thick alluvial sediments of the river. Due to the preservation in the still moist soil environment, a number of plant remains were preserved, which could be archaeobotanically examined by the Botanical Institute of the University of Hohenheim .

Riparian plants

Soil samples have been taken continuously from the start of the excavations. At the end of the investigation - 1986 - a total of 40 samples were available, which were stratigraphically and botanically checked. Before the arrival of the Romans, the valley floor consisted of natural peat and clayey flood layers. Relatively strongly decomposed remains of various types of sedges , reeds and other plant remains that are typical of high herbaceous reeds had been preserved in the peat . Based on the degree of decomposition, it could be concluded that the floodplains were repeatedly dry for parts of the year. These dry phases were interrupted by clayey flood layers, which indicated the high water levels of the Kirnau.

The Romans erected the first buildings above the reed. Before that, they had probably mowed the vegetation and then put a layer of leveling soil on which the consecration district was then established. The plant remains recovered from the Roman layers could be assigned to 158 species. Of the 11,163 plant remains in the samples, 10,571 were identified as wild plants. Of these, the weeds and ruderal plants were the most common. Significant remains were also left behind by the riverbank plants and tall shrub reeds that existed in the flood area. They needed moist, nutrient-rich soils. However, they were only in the water during floods. In dry periods the reed was accessible. Also worth mentioning are the aquatic plants found, which prefer wet meadows as well as moist to moderately dry and low, poor meadows.

Trees

The forest may not have been far from the shore in Roman times. A total of 16 forest-dwelling plants were represented. The twigs and branches that were not processed by human hands could be identified as oak (53.3%), hazel (20%), beech (13.1%), maple (5.0%), alder (2.7%) ), Birch (2.3%), fir (1.3%), willow (0.9%) and black elder (0.9%). In the processed woods, oak was even more important. Also for the woods determined by deductions, mainly oak and, to a lesser extent, maple and beech were determined. Of the three pieces of fir wood found, only the remainder of an eight to ten-year-old trunk belonged directly to a young tree, the others were just twigs. The presence of a Christmas tree in the ancient sanctuary, which was atypical for the region at that time, can only be explained by the presence of the Romans, who either brought the tree from afar or planted it on site.

Crops

Many traces of the useful plants cultivated in the vicinity of the camp village can also be found in Roman times. A total of 592 remains that could be assigned to 20 species and genera were found. Pieces of seed husks from cereals were found to be the most important representatives of the useful plants, with spelled playing a particularly important role. It is also known from other Roman settlements that spelled played an important role in feeding the Roman population of that time. The building land in Baden , to which Osterburken belongs, is still one of the most important spelled growing areas in Germany. Possibly this tradition is based on Roman roots. In addition to the spelled, barley was found to a lesser extent. In addition, there were culinary herbs such as coriander, dill and celery as well as abundant traces of collective fruits such as blackberries, wild strawberries and raspberries. Only figs and olives were recognizable as typically Roman imports.

Other important militaria

From the fort area comes a Roman iron helmet with an upward-pointing forehead and a low neck shield. The cheek flaps obviously attached to the inside of the helmet were missing when they were found. The now lost, well-preserved helmet came to the “Museum of Mannheim” and has remained a unique specimen to this day. The cut-outs for the ears are very large in this model, and the rounded earmuffs are made directly from the material of the dome. The large forehead protection is attached to the side of the helmet shell with two rivets, which are located directly above the forehead edge. In terms of type, this helmet is a typical further development of the Weisenau model . In contrast to other representatives of this type, the forehead protection, which is steeply upward, can, in the opinion of weapons expert H. Russell Robinson, also be found on grave stelae of cavalry soldiers. The representations he presented, however, came from the 1st century AD. Robinson classified the piece, which he dated to the middle of the 3rd century AD, as an auxiliary infantry helmet A (= Auxiliary Infantry I).

Lost property

Roman finds from Osterburken are now in the Roman Museum on site, in the Limes Museum in Aalen , in the Schwäbisch- Hall Museum in Schwäbisch Hall , in Mannheim ( Reiss-Engelhorn Museum ) and in the Badisches Landesmuseum in Karlsruhe .

Monument protection

The Osterburken fort and the aforementioned ground monuments have been part of the UNESCOS World Heritage as a section of the Upper German-Rhaetian Limes since 2005 . In addition, the facilities are cultural monuments according to the Monument Protection Act of the State of Baden-Württemberg (DSchG) . Investigations and targeted collection of finds are subject to approval, and accidental finds are reported to the monument authorities.

See also

- List of forts on the Upper German-Raetian Limes

- Osterburken Roman Museum

- Beneficiary consecration district Osterburken

literature

- Géza Alföldy : The linear demarcation of the front Limes in Upper Germany and the governorship of Gaius Popilius Carus Pedo . In: Egon Schallmayer (Ed.): Limes Imperii Romani. Contributions to the specialist colloquium “World Heritage Limes” November 2001 in Lich-Arnsburg (= Saalburg-Schriften. 6). Roman fort Saalburg, Archaeological Park, Bad Homburg v. d. H. 2004, ISBN 3-931267-05-9 , pp. 7-20.

- Dietwulf Baatz : The Roman Limes. Archaeological excursions between the Rhine and the Danube . 4th edition, Mann, Berlin 2000, ISBN 3-7861-2347-0 , pp. 234f.

- Dietwulf Baatz: Brick stamp of the 8th Legion from Osterburken, Fort Bath II. In: Find reports from Baden-Württemberg. 13, 1988, p. 213ff.

- Dietwulf Baatz: Stamped bricks of the 8th Legion from Osterburken. In: Find reports from Baden-Württemberg. 4, 1979, pp. 130ff.

- Dietwulf Baatz, Rolf-Heiner Behrends: Investigations at the Roman fort bath in Osterburken, Neckar-Odenwald district. In: Find reports from Baden-Württemberg. 3, Stuttgart 1977, p. 265ff.

- Willi Beck, Dieter Planck : The Limes in Southwest Germany. 2nd edition, Theiss, Stuttgart 1987, ISBN 3-8062-0242-7 .

- Thomas Becker: Viewed from two sides. Considerations for the Limes wall between Osterburken-Bofsheim and Jagsthausen on route 8 . In: Andreas Thiel (Ed.): Research on the function of the Limes. 3rd specialist colloquium of the German Limes Commission 17./18. February 2005 in Weißenburg i. Bay. (= Contributions to the Limes World Heritage Site. 2), Theiss, Stuttgart 2007, ISBN 978-3-8062-2117-6 , pp. 91-105.

- Rolf-Heiner Behrends: Investigations at the Roman fort bath of Osterburken, Odenwaldkreis. In: Denkmalpflege in Baden-Württemberg , 3 (1974), pp. 31–34.

- Ernst Fabricius , Felix Hettner , Oscar von Sarwey (ed.): The Upper Germanic-Raetian Limes of the Roman Empire . Volume 4: Stretches 7 to 9 (The Upper German Limes from Miltenberg am Main to Haghof near Welzheim). Petters, Heidelberg 1931 and 1933.

- Anita Gaubatz-Sattler and Wolfgang Seidenspinner: Osterburken . LDA Baden-Württemberg, Stuttgart 2001, ISBN 3-927714-59-3 .

- Siegbert Huther, Egon Schallmayer: The Beneficiarier Consecration District of Osterburken: Elite soldiers of the governor on the Limes. In: Imperium Romanum - Romans, Christians, Alamanni - The late antiquity on the Upper Rhine. Exhibition catalog, Theiss, Stuttgart 2005, ISBN 3-8062-1954-0 , pp. 214-216.

- Klaus Kortüm : A bathroom makes history. In: Archeology in Germany. 1/2006, Stuttgart 2006.

- Klaus Kortüm: The Roman fort bath of Osterburken - an interim report. In: Archaeological News from Baden. 71, Freiburg im Breisgau 2005, pp. 22-30.

- Klaus Kortüm: From the Roman fort bath to the medieval city. Excavations in the center of Osterburken, Neckar-Odenwald district. In: Archaeological excavations in Baden-Württemberg 2005. 26, 2006, pp. 135–139.

- Klaus Kortüm: New studies on the Roman fort bath of Osterburken, Neckar-Odenwald district. In: Archaeological excavations in Baden-Württemberg 2004. 25, 2005, pp. 144–148.

- Britta Rabold : On the trail of the Limes. Investigations of a section of route 8 south of Osterburken . In: Andreas Thiel (Ed.): The Limes as UNESCO World Heritage (= contributions to the Limes World Heritage. 1), Theiss, Stuttgart 2008, ISBN 978-3-8062-2118-3 , pp. 105-109.

- Britta Rabold, Egon Schallmayer, Andreas Thiel: Der Limes , Theiss, Stuttgart 2000, ISBN 3-8062-1461-1 .

- Fridolin Reutti: On the state of knowledge of the Roman Osterburken. In: Find reports from Baden-Württemberg. 4, 1979, p. 230ff.

- Egon Schallmayer and Klaus Kortüm in Dieter Planck (ed.): The Romans in Baden-Württemberg. Roman sites and museums from Aalen to Zwiefalten. Theiss, Stuttgart 2005, ISBN 3-8062-1555-3 , p. 243ff.

- Egon Schallmayer u. a. (Ed.): The Roman consecrated district of Osterburken II. Colloquium 1990 and paleobotanical-osteological investigations (= research and reports on prehistory and early history in Baden-Württemberg. 44), Theiss, Stuttgart 1994, ISBN 3-8062-1140-X .

- Egon Schallmayer: Final excavation of the Roman burial ground “Affeldürn” in Osterburken, Neckar-Odenwald district. In: Archaeological excavations in Baden-Württemberg 1992. 1993, pp. 159–162.

- Egon Schallmayer: A Roman coin treasure from Osterburken, Neckar-Odenwald district. In: Archäologische Ausgrabungen in Baden-Württemberg 1992. 1993, pp. 125–129.

- Egon Schallmayer u. a. (Ed.): The Roman consecrated district of Osterburken I. Corpus of the Greek and Latin beneficiarier inscriptions of the Roman Empire (= research and reports on prehistory and early history in Baden-Württemberg. 40), Theiss, Stuttgart 1991, ISBN 978-3 -8062-0854-2 .

- Egon Schallmayer: A cult center of the Romans in Osterburken. In: Dieter Planck (Ed.): The Celtic Prince of Hochdorf. Methods and results of state archeology. Theiss, Stuttgart 1985, ISBN 3-8062-0441-1 , pp. 377-407.

- Egon Schallmayer: excavation of a beneficiary consecration district and Roman wooden buildings in Osterburken. In: 13th International Limes Congress Aalen 1983. Theiss, Stuttgart 1986, ISBN 3-8062-0776-3 , pp. 256-261.

- Egon Schallmayer: Roman excavations in Neckarburken, Osterburken and Walldürn. In: Preservation of monuments in Baden-Württemberg. 12, 1983, pp. 136-142.

- Jörg Scheuerbrandt et al .: The Romans in the area of the Neckar-Odenwald district. Frontier zone of the Roman Empire . Regional culture, Ubstadt-Weiher 2009, ISBN 978-3-89735-524-8 .

- Jörg Scheuerbrandt: Tourist development and sustainable protection . In: The Limes. News bulletin of the German Limes Commission. 1/2012, p. 26f. ( PDF , accessed on September 6, 2012).

- Ute Schillinger-Häfele: New inscriptions from Osterburken. In: Find reports from Baden-Württemberg. 1, 1974, pp. 533-544.

- Karl Schumacher in: The Upper Germanic-Raetian Limes of the Roman Empire (Eds. Ernst Fabricius, Felix Hettner, Oscar von Sarwey): Department B, Volume 4, Fort No. 40 (1895).

- Gabriele Wesch-Klein: Another component of the 22nd Legion from Osterburken, Neckar-Odenwaldkreis. In: Find reports from Baden-Württemberg. 13, 1988, pp. 709-711.

Web links

- Kastell Osterburken on the website of the German Limes Commission

- Official website of the Römermuseum Osterburken

- Kastell Osterburken on the website of the head office for educational media on the Internet (ZUM)

Remarks

- ↑ a b c Willi Beck, Dieter Planck : The Limes in Southwest Germany. 2nd edition, Theiss, Stuttgart 1987, ISBN 3-8062-0242-7 , p. 49.

- ↑ Ulrike Wels-Weyrauch: The pendants and neck rings in southwest Germany and northern Bavaria. Beck, Munich 1978, ISBN 3-406-00771-6 , p. 164.

- ^ Willi Beck, Dieter Planck : The Limes in Southwest Germany. 2nd edition, Theiss, Stuttgart 1987, ISBN 3-8062-0242-7 , p. 55.

- ↑ a b Udelgard Körber-Grohne : Gramineae and grassland vegetation from the Neolithic to the Middle Ages in Central Europe. Schweizerbart'sche Verlagsbuchhandlung, Stuttgart 1990, ISBN 3-510-48010-4 , p. 71.

- ↑ a b Dietwulf Baatz: The Roman Limes. Archaeological excursions between the Rhine and the Danube. Mann, Berlin 1993, ISBN 3-7861-1701-2 , p. 229.

- ^ A b Anne Johnson (German adaptation by Dietwulf Baatz): Roman forts . von Zabern, Mainz 1987, ISBN 3-8053-0868-X , p. 315.

- ^ Karl Wilhelmi: Seventh Annual Report to the Members of the Sinsheim Society for Research into the Patriotic Monuments of Prehistoric Times. Sinsheim 1840, p. 77.

- ^ A b Britta Rabold , Egon Schallmayer , Andreas Thiel : Der Limes. The German Limes Road from the Rhine to the Danube. Theiss, Stuttgart 2000, ISBN 3-8062-1461-1 , p. 78.

- ↑ a b Karl Wilhelmi: Seventh Annual Report to the Members of the Sinsheim Society for Research into the Patriotic Monuments of Prehistoric Times. Sinsheim 1840, pp. 73, 76.

- ^ Dietwulf Baatz: Stamped bricks of the 22nd Legion from the fort bath of Osterburken (excavation 1973). In: Dietwulf Baatz, Rolf-Heiner Behrends: Investigations at the Roman fort bath in Osterburken, Neckar-Odenwald district. In: Find reports from Baden-Württemberg. 3, Stuttgart 1977, p. 265ff .; here p. 271.

- ↑ a b c Willi Beck, Dieter Planck : The Limes in Southwest Germany. 2nd edition, Theiss, Stuttgart 1987, ISBN 3-8062-0242-7 , p. 51.

- ↑ a b c d e f g Dieter Planck: The Romans in Baden-Württemberg. Roman sites and museums from Aalen to Zwiefalten. Theiss, Stuttgart 2005, ISBN 3-8062-1555-3 , p. 246.

- ^ Philipp Filtzinger , Dieter Planck, Bernhard Cämmerer: The Romans in Baden-Württemberg. Theiss, Stuttgart 1986, ISBN 3-8062-0287-7 , p. 468.

- ↑ Schallmayer: Final excavations of the Roman burial ground “Affeldürn” in Osterburken, Neckar-Odenwald district . In: Archaeological excavations in Baden-Württemberg 1992. pp. 159–162.

- ↑ a b Rudolf Pörtner : With the elevator to Roman times . Econ, Düsseldorf / Vienna 1984, ISBN 3-430-17529-1 , p. 188.

- ↑ a b c d e f Britta Rabold, Egon Schallmayer, Andreas Thiel: Der Limes. The German Limes Road from the Rhine to the Danube. Theiss, Stuttgart 2000, ISBN 3-8062-1461-1 , p. 79.

- ↑ Melanie Müller: Receive beautiful things and benefit from them . www.fnweb.de, July 21, 2012; accessed on September 24, 2016.

- ↑ a b c Willi Beck, Dieter Planck : The Limes in Southwest Germany. 2nd edition, Theiss, Stuttgart 1987, ISBN 3-8062-0242-7 , p. 53.

- ^ Willi Beck, Dieter Planck : The Limes in Southwest Germany. 2nd edition, Theiss, Stuttgart 1987, ISBN 3-8062-0242-7 , p. 56.

- ↑ Hans-Peter Kuhnen (Ed.): Stormed - Cleared - Forgotten? The Limesfall and the end of Roman rule in southwest Germany. Accompanying volume for the special exhibition from May 28th – 1st November 1992 in the Limesmuseum Aalen, Theiss, Stuttgart 1992, ISBN 3-8062-1056-X , p. 109.

- ^ Klaus Kortüm: Osterburken. Roman border post between Neckar Valley and Taubergrund. In: Preservation of monuments in Baden-Württemberg. 35, 1/2006, p. 39. ( PDF ( Memento of the original from January 14, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link has been inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice . )

- ↑ Géza Alföldy: The linear demarcation of the Front Limes in Upper Germany and the governorship of Gaius Popilius Carus Pedo . In: Egon Schallmayer (Ed.): Limes Imperii Romani. Contributions to the specialist colloquium “World Heritage Limes” November 2001 in Lich-Arnsburg (= Saalburg-Schriften 6). Roman fort Saalburg, Archaeological Park, Bad Homburg v. d. H. 2004, ISBN 3-931267-05-9 , pp. 7-20.

- ↑ Claus-Michael Hüssen: The Roman settlement in the area around Heilbronn. Theiss, Stuttgart 2000, ISBN 3-8062-1493-X , p. 145.

- ^ A b Klaus Kortüm: Osterburken. Roman border post between Neckar Valley and Taubergrund. In: Preservation of monuments in Baden-Württemberg. 35, 1/2006, p. 41.

- ↑ AE 1996, 1166 .

- ↑ Egon Schallmayer, Gerhard Preuß: The stone finds from the sanctuary of Osterburken. In: Egon Schallmayer u. a. (Ed.): The Roman consecrated district of Osterburken II. Colloquium 1990 and paleobotanical-osteological investigations (= research and reports on prehistory and early history in Baden-Württemberg. 44), Theiss, Stuttgart 1994, ISBN 3-8062-1140-X , Pp. 15-73; here: p. 26.

- ↑ a b c d e f g Klaus Kortüm: Osterburken. Roman border post between Neckar Valley and Taubergrund. In: Preservation of monuments in Baden-Württemberg. 35, 1/2006, p. 44.

- ^ Bernhard Albert Greiner: The contribution of the dendrodata from Rainau book to the Limesdatierung. In: Limes XX. Estudios sobre la frontera Romana. Ediciones Polifemo, Madrid 2009, ISBN 978-84-96813-25-0 , p. 1289.

- ^ AE 1986, 523 .

- ↑ CIL 13, 11766 .

- ↑ Egon Schallmayer: The Odenwald Limes. Theiss, Stuttgart 2010, ISBN 978-3-8062-2309-5 , p. 26.

- ^ Klaus Kortüm: Osterburken. Roman border post between Neckar Valley and Taubergrund. In: Preservation of monuments in Baden-Württemberg. 35, 1/2006, p. 46.

- ↑ Bernd Becker: Felling dates of Roman construction timbers based on a 2350 year old South German oak tree ring chronology . In find reports from Baden Württemberg . Volume 6, Theiss, Stuttgart 1981, ISBN 3-8062-1252-X , p. 386.

- ↑ CIL 13, 6561 .

- ↑ a b Willi Beck, Dieter Planck : The Limes in Southwest Germany. 2nd edition, Theiss, Stuttgart 1987, ISBN 3-8062-0242-7 , p. 50.

- ^ Günter Ulbert, Thomas Fischer: Der Limes in Bayern , Theiss, Stuttgart 1983, ISBN 3-8062-0351-2 , p. 99.

- ↑ CIL 13, 6583 .

- ↑ CIL 13, 11769 .

- ↑ Felix Hettner: Report on the activities of the Reichslimeskommission from the end of November 1896 to the end of December 1897. In: Archäologischer Anzeiger. Supplement to the yearbook of the German Archaeological Institute. 1898, Georg Reimer, Berlin 1899, p. 21 ( online ).

- ^ A b Karl Schumacher: Osterburken. (Building inscription from the fort.) In: Limesblatt: Notices from the route commissioners to the Reichslimeskommission. No. 24 (September 30, 1897), pp. 667 ff .; here: pp. 667–668.

- ^ A b c Philipp Filtzinger, Dieter Planck, Bernhard Cämmerer: The Romans in Baden-Württemberg. Theiss, Stuttgart 1986, ISBN 3-8062-0287-7 , p. 470.

- ↑ CIL 13, 6578 .

- ↑ CIL 13, 06578a .

- ↑ CIL 13, 6582 .

- ^ Britta Rabold, Egon Schallmayer, Andreas Thiel: Der Limes. The German Limes Road from the Rhine to the Danube. Theiss, Stuttgart 2000, ISBN 3-8062-1461-1 , pp. 79-80.

- ↑ CIL 16, 20 .

- ↑ CIL 16, 28 .

- ↑ CIL 16, 36 .

- ^ AE 2004, 1910 .

- ^ AE 2003, 2056 .

- ↑ CIL 16, 62 .

- ^ AE 1982, 718 .

- ↑ CIL 16, 80 .

- ↑ Dietwulf Baatz: On the dating of the bath at the Limeskastell Stockstadt. In: Bavarian history sheets . 34, 1969, pp. 63-75.

- ↑ CIL 13, 6490 .

- ↑ CIL 13,6575 .

- ↑ CIL 13, 6567 .

- ↑ CIL 13, 6569 .

- ↑ CIL 13, 11767 .

- ↑ a b CIL 13, 6566 .

- ↑ CIL 13,6568 .

- ↑ CIL 13, 6569 .

- ↑ CIL 13, 6584 .

- ↑ CIL 13, 6585 .

- ↑ CIL 13, 6586 .

- ^ AE 1978, 530 .

- ↑ Kohortenbad Osterburken at 49 ° 25 '47.32 " N , 9 ° 25' 33.38" O .

- ^ Augsburgische Ordinari postal newspaper. Augsburg 1826, p. 3 (without page number).

- ^ Dietwulf Baatz, Rolf-Heiner Behrends in: Find reports from Baden-Württemberg. 3, 1977, p. 265.

- ↑ Numerusbad Osterburken at 49 ° 25 '45.82 " N , 9 ° 25' 32.01" O .

- ↑ CIL 13, 6592 .

- ↑ Dietwulf Baatz: The bathing building of the Limes fort Walldürn (Odenwaldkreis). In: Saalburg yearbook . 35, de Gruyter, Berlin 1978, pp. 61-107, here: p. 88.

- ↑ Hans Ulrich Nuber : Excavations on the Schirenhof (Schwäbisch Gmünd) . In: Studies on the military borders of Rome II. Habelt, Bonn 1977, ISBN 3-7927-0270-3 , p. 229.

- ^ Dieter Planck, Willi Beck: The Limes in Southwest Germany . 2nd, completely revised edition, Theiss, Stuttgart 1987, ISBN 3-8062-0496-9 , p. 109.

- ^ A b Bernhard Albert Greiner: The fort vicus of Rainau book: History of settlements and correction of the dendrochronological data . In: Ludwig Wamser, Bernd Steidl: New research on Roman settlement between the Upper Rhine and Enns . Greiner, Remshalden-Grunbach 2002, ISBN 3-935383-09-6 , pp. 85 and 88.

- ↑ Dieter Planck: New research on the Upper Germanic and Raetian Limes . In: Hildegard Temporini (ed.): The rise and fall of the Roman world . Volume II, 5, 1, de Gruyter, Berlin 1976, ISBN 3-11-006690-4 , p. 426.

- ↑ Oscar Paret: The settlements of the Roman Württemberg. In: Friedrich Hertlein , Oscar Paret, Peter Goessler (ed.): The Romans in Baden-Württemberg. Volume 3, 1. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 1932, p. 149.

- ↑ Hans-Peter Kuhnen in: Hans-Peter Kuhnen (Ed.): Stormed - Cleared - Forgotten? The Limesfall and the end of Roman rule in southwest Germany. Accompanying volume for the special exhibition from May 28th – 1st November 1992 in the Limesmuseum Aalen, Theiss, Stuttgart 1992, ISBN 3-8062-1056-X , p. 37; Martin Luik : The reduction of the fort baths - signs of a lack of raw materials? In: Hans-Peter Kuhnen (Ed.): Stormed - Cleared - Forgotten? The Limesfall and the end of Roman rule in southwest Germany. Accompanying volume for the special exhibition from May 28th – 1st November 1992 in Limesmuseum Aalen, Theiss, Stuttgart 1992, ISBN 3-8062-1056-X , pp. 68-70.

- ^ Dieter Planck, Willi Beck: The Limes in Southwest Germany . 2nd, completely revised edition, Theiss, Stuttgart 1987, ISBN 3-8062-0496-9 , p. 35.

- ↑ The Roman Easter Burken. A római Osterburken. (without naming the author) In: On behalf of the eagle. A római sas szolgálatában. Publius Ferrasius Avitus. Book accompanying the German-Hungarian special exhibition 2012. ISBN 978-3-00-037759-4 , p. 116.

- ^ A b Dieter Planck: The Romans in Baden-Württemberg. Roman sites and museums from Aalen to Zwiefalten. Theiss, Stuttgart 2005, ISBN 3-8062-1555-3 , p. 248.

- ↑ CIL 13, 6576 .

- ^ Günter Ulbert, Thomas Fischer: Der Limes in Bayern , Theiss, Stuttgart 1983, ISBN 3-8062-0351-2 , p. 99.

- ^ Britta Rabold, Egon Schallmayer, Andreas Thiel: Der Limes. The German Limes Road from the Rhine to the Danube. Theiss, Stuttgart 2000, ISBN 3-8062-1461-1 , p. 81.

- ^ Philipp Filtzinger , Dieter Planck, Bernhard Cämmerer: The Romans in Baden-Württemberg. Theiss, Stuttgart 1986, ISBN 3-8062-0287-7 , p. 446.

- ^ Karl Wilhelmi: Seventh Annual Report to the Members of the Sinsheim Society for Research into the Patriotic Monuments of Prehistoric Times. Sinsheim 1840, pp. 81-82, 85.

- ^ Karl Schumacher: Osterburken. (Building inscription from the fort.) In: Limesblatt: Notices from the route commissioners to the Reichslimeskommission. No. 24 (September 30, 1897), pp. 667 ff .; here: p. 667.

- ^ Karl Schumacher: The Osterburken fort. In: The Upper Germanic-Raetian Limes of the Roman Empire. Dept. B, Volume IV, p. 28.

- ↑ Claudia Theune-Vogt : Teutons and Romanes in the Alamannia (= supplementary volumes to the Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde. Vol. 45). Walter de Gruyter, Berlin 2004, ISBN 3-11-017866-4 , p. 91.

- ↑ Joachim Henning: On the dating of tool and agricultural equipment finds in the Germanic land acquisition area between the Rhine and the Upper Danube (The Hort find of Osterburken). In: Yearbook of the Roman-Germanic Central Museum. 32nd year, 1985, p. 570ff .; here pp. 573-575.

- ↑ CIL 13, 6561 .

- ↑ a b c d e Brigitte Fröschle: Botanical investigation of Roman plant remains from the archaeological excavation in Osterburken. In: Egon Schallmayer u. a. (Ed.): The Roman consecrated district of Osterburken II. Colloquium 1990 and paleobotanical-osteological investigations (= research and reports on prehistory and early history in Baden-Württemberg. 44), Theiss, Stuttgart 1994, ISBN 3-8062-1140-X , Pp. 319-362; here: p. 359.

- ↑ Brigitte Fröschle: Botanical investigation of Roman plant remains from the archaeological excavation in Osterburken. In: Egon Schallmayer u. a. (Ed.): The Roman consecrated district of Osterburken II. Colloquium 1990 and paleobotanical-osteological investigations (= research and reports on prehistory and early history in Baden-Württemberg. 44), Theiss, Stuttgart 1994, ISBN 3-8062-1140-X , Pp. 319-362; here: p. 334.

- ↑ Egon Schallmayer: Introduction. (Part 2) In: Egon Schallmayer u. a. (Ed.): The Roman consecrated district of Osterburken II. Colloquium 1990 and paleobotanical-osteological investigations (= research and reports on prehistory and early history in Baden-Württemberg. 44), Theiss, Stuttgart 1994, ISBN 3-8062-1140-X , P. 317.

- ^ H. Russell Robinson: The armor of imperial Rome. Arms and Armor Press, 1975, ISBN 0-85368-219-4 , p. 104.