Großprüfening small fort

| Großprüfening small fort | |

|---|---|

| limes | ORL NN ( RLK ) |

| section |

Raetian Limes ; Danube-Iller-Rhine-Limes |

| Dating (occupancy) | a) late 2nd century AD until 259/260 AD at the latest b)? c)? |

| Type | a) Small fort b) Remaining fort? c) Burgus |

| size | a) Small fort: 60 × 80 m (= 0.48 ha) b) Remaining fort:? c) Burgus: 7 × 6.25 m |

| Construction | stone |

| State of preservation | The invisible facility is located on an agriculturally intensively used corridor. |

| place | Großprüfening-Dech Betten-Königswiesen |

| Geographical location | 49 ° 1 '3.4 " N , 12 ° 2' 13.4" E |

| height | 340 m above sea level NHN |

| Previous | Small fort Alkofen (southwest) |

| Subsequently | Kumpfmühl fort (east) |

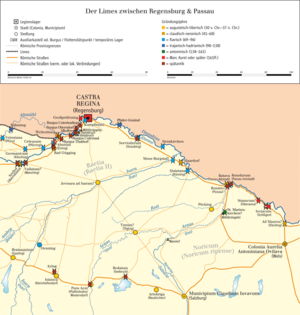

The Großprüfening small fort is a former Roman military camp on the “wet Limes” of the Raetian Danube border . The find area is in today's Großprüfening-Dech Betten-Königswiesen district west of the independent city of Regensburg in the Bavarian administrative district of Upper Palatinate .

location

The location on the gently sloping lower terrace in a large Danube loop stretching to the northwest attracted people very early on. The land rises slightly to the southeast in particular. However, more dominant groups of hills are mainly found on the southern bank. The location between the Naab which flows here and the rain flowing in to the northeast was certainly important for the location early on . The small fort is still in close proximity to the river. As a direct connection to the north, the Naabsenke played an important role in the past.

Research history

Open-air stations already existed in the area of the ancient usable area in the end Paleolithic and Mesolithic . These were followed by settlements from the Neolithic , the Urnfield Culture , and the Late Hallstatt Period . The moat of a manor is also from Hallstatt. Later branches of the early and late latène period followed . The field name “Schanzacker” indicates the at least partially military background of the site. In 1911 traces of Roman settlement were discovered on the right bank of the Danube in the area of the mouth of the Naab. At that time a first excavation took place under the direction of the prelate Johann Baptist Mehler (1860–1930). During this research, the most spectacular find is said to have emerged from the ground as a “gold-plated” helmet, which was immediately lost. He was followed in 1913 by the classical philologist Georg Steinmetz (1850–1945) with a new investigation in the camp village. A Roman cellar was also examined for Schanzacker, which revealed, among other things, partially stamped Terra Sigillata from Rheinzabern (Belsus f; Mammilianus f.) And three coins. The final coin of the cellar came from the reign of Emperor Gordian III. (238-244). The findings of a settlement already indicated the possible existence of a fort at this point. The Danube canalization repeatedly made smaller rescue excavations necessary in the area of the camp village ( vicus ) . Finally, its overall extent could be measured and the two burial grounds examined. The small fort, hidden under intensively used agricultural areas, was not identified until 1977 on the basis of photographs taken by aerial photo archaeologist Otto Braasch . A smaller excavation was carried out on its northern corner as early as 1978. The foundations of the surrounding wall and the corner tower there were recorded. In addition, the trench system could be cut. In the following year, the south-eastern weir ditch was uncovered by means of a 90-meter-long cut. The excavations were directed by the prehistorian Udo Osterhaus . A large number of aerial photographs are now available, which also give an insight into the interior of the camp. In late autumn 2010, a geophysical prospecting took place on the area of the small fort.

After its restoration, the foundations of an 8 × 13 meter farm building from the camp village ( vicus ) uncovered in 1978 were preserved under a protective structure from the excavations . The building, interpreted as a kiln , could also have included a brewery.

Building history

Principate

The almost 60 × 80 meters (= 0.48 hectare) small fort was built at the same time or a short time after the establishment of the Regensburg legionary camp, which was completed in 179 AD . The complex, with its praetorial front and the Porta praetoria (main gate), oriented to the south-west, follows the standardized building scheme of the middle imperial period. The rectangular surrounding wall has rounded corners (playing card shape) and each a slightly trapezoidal corner tower. There are no intermediate towers. A single-lane gate leads into the interior of the fort on all four sides. The gates are flanked by two rectangular gate towers. As the investigations of 1978 and 1979 show, the enclosing wall had collapsed into the moat surrounding the small fort, at least within the known sections. On the south-eastern flank, this wall could be measured with a width of one or 1.20 meters. From the partially almost complete collapse of the wall, a minimum height of eight meters for the original defensive wall could be calculated. The inside of the wall showed strong traces of fire, which indicated that the battlement did not run on an embankment, but was built as a wooden structure.

The pointed ditch, measured around 94 × 78 meters at the outer edges, was between five and 5.5 meters wide, partly in two phases. The berm between the trench system and the defensive wall was around 2.10 meters wide. Only in front of the Porta decumana , the rear camp gate on the northeastern narrow side, did this trench exposed over a width of around three meters. At all three other entrances it had to be overcome by means of a wooden bridge. According to evidence of the find, the younger ditch was apparently filled in in the last quarter of the 3rd century.

By merging the aerial photos with the first magnetogram in 2010, some statements about the interior development can be made. At the intersection of the camp streets coming from all four gates was the rectangular, approximately 19 × 15 meter staff building ( Principia ) . The investigations also testify to a flag sanctuary with a rounded apse on the rear long side. Evidence of this sanctuary shows that the troops lying there had their own standard and operated as an independent tactical unit. For the south-eastern narrow side of the Principia three adjacent rooms are attested. Most likely the opposite narrow side was constructed accordingly. A small inner courtyard is assumed to be in the center of the staff building. Another small building of around 2.25 × 2.87 meters can be seen in the Praetentura - the rear storage area behind the Principia - on the axis of the Via decumana leading to the rear gate . Another rectangular building is located near the south corner of the fort and is around 7.86 × 5.70 meters in size.

The small fort was located on a Roman road running along the Danube and probably had the task of militarily monitoring the mouth of the Naab Valley. The complex, which is probably occupied by two centuries, was possibly during the reign of Emperor Gordian III. set on fire with the camp village in the second Alemanni storm of 242/243 AD. In the finds processed by archaeologist Thomas Fischer until 1976, the series of coins with this emperor ended. At the latest in AD 259/260, in the course of the Limes Falls , the facility was finally abandoned. The finds do not extend beyond the last quarter of the 3rd century.

Late antiquity

As some findings suggest, Großprüfening could have been put back into service as a reduction fort or Burgus during late antiquity. A small weir system may have been built into the north corner at a point in time that has not yet been determined. Among other things, this suggests a more recent, semicircular trench with an earth bridge, which cuts the older structures and the trench, which was filled in in the last quarter of the 3rd century. In front of the Praetorial Front, on the arterial road leading to the Danube, a small rectangular building was erected directly on the moat. A similar finding that came to light at Fort Wörth is ascribed to a late antique period. In addition to the building findings, a few finds from the small fort and from the camp village testify that there was still Roman life in Großprüfening at the end of the 5th century. Among the finds are remains of late antique belt sets and a half centenionalis from the reign of Emperor Arcadius (395–408).

Vicus

About a kilometer long and an average of 150 to 250 meters wide, the vicus, the camp village belonging to the small fort, stretched from southwest to northeast along the Roman road. By 1979, at least 14 scattered individual buildings and two complete building complexes on Kornweg had been examined. The strip houses , some of which have a stone cellar, were built using clay framework technology. Public buildings are not known. In 1977 the bronze cheek flap of a rider's helmet was found in one of the earth cellars, which still showed traces of the silver-colored tinning. In addition to the smaller strip houses, there were also larger, single-storey commercial buildings. On the basis of the finds, various craft businesses have been identified in the vicus. According to the finds, bronze foundries were also among the residents. In addition to metal processing companies, the production of textiles for the vicus is also documented using tools such as flax combs, which were used in linen production and were found in two buildings. In addition, kilns were often found. According to coins, the vicus came to an end around AD 259/260, after extensive destruction had already taken place during the Alemanni invasion of 242/243. This end time is documented by the skull of a male person from the vicus who was slain with a sword and remained unburied. Another testimony from the time of the downfall are two forcibly destroyed iron shield bosses that were found in a cellar filled with fire rubble from the middle of the 3rd century. The term post quem for this event is a Limes falsum by the imperial mother Julia Mamaea (murdered March 235). In the same basement, however, there was also an undamaged iron shield boss.

Around 20 meters from the south-eastern moat, a magnetometer was discovered in 2010, a furnace with a diameter of 6.70 meters and an oval, 28 × 10 meter distribution of fire rubble. Three more smelting furnaces stood along the weir ditch that ran parallel to the Danube. All four ovens did not work at the time of the Middle Imperial garrison. It is not known when they were in operation.

Only in a few cases have such a complete spectrum of finds from everyday life come down to us from the mid-imperial incendiary layers of a camp village as from Großprüfening. In addition to handicraft tools, there were among other things table and kitchen utensils, jewelry and hairpins. In addition, leg plates for tablet weaving and ceramic molds for cheese production came to light. In addition, bone game pieces and bronze candle holders document the modest standard of living in the settlement.

Burial grounds

Two burial grounds belonged to the fort and vicus, with the one at the western corner of the fort, after being occupied only briefly towards the end of the second century, finally abandoned and overbuilt in the third century. In the larger cemetery, which has not yet been completely excavated, there were over 100 cremation graves as well as the body burials of infants and one adult. Grave goods such as bronze belt fittings and iron shoe nails indicate that soldiers and veterans were also buried on the cemetery. Otherwise the additions consisted of bronze jewelry, glass mirrors, oil lamps, glass and ceramic vessels, incense goblets and cutlery.

Late Roman fortifications

At the southwest end of the settlement, the remains of a burgus with 7 × 6.25 meters and walls up to one meter thick have been explored. A weir ditch, which is normally characteristic for this type of building, is not documented here. The beginning and end of the structure cannot be dated in more detail due to the sparse finds. The tower's foundations, however, cut fire rubble pits and 3rd century destruction, which makes a late Roman dating likely.

Villa Rustica double beds

To the southeast of the garrison, a villa rustica was excavated in the Dech Betten district during the construction of a new building area in 2001, immediately north of the street “An der Brunnenstube” . The main building, which was structured around a square inner courtyard, was just over 200 square meters in size and had two accentuated corner projections on the representative front , in which the rooms used for residential purposes were located. One room was hypocaust . The finds included two lance tips and an Omega fibula as well as Terra Sigillata. According to the findings, the estate was built during the first half of the 3rd century and destroyed again around 242/243 - during the second Alemanni invasion.

Post-Roman development

An immediate post-Roman settlement continuity cannot be proven. In anticipation of the shooting of a planned new development area, rescue excavations took place in 2003/2004 and 2005/2006 on the lower terrace of Großprüfening between Kornweg, Rennweg and Roter Brach Weg, immediately south of the ancient structures. A small early medieval cemetery field was uncovered, which contained a total of 22 burial sites and 20 circular trenches. The circular moats were possibly part of leveled burial mounds. Based on the findings, the facility was used from the middle of the 6th century to the first third of the 7th century AD. The origin of the findings suggests possibly Slavic immigrants from the central Danube region. Perhaps the migration of this group is related to the evacuation of Pannonia by the Lombards . The Lombards migrated to Italy at this time and left their settlement areas to the Avars .

Monument protection

The facilities mentioned are protected as registered ground monuments within the meaning of the Bavarian Monument Protection Act (BayDSchG) . Investigations and targeted collection of finds are subject to authorization, accidental finds must be reported to the monument authorities.

See also

literature

- Andreas Boos: A brewery from the Roman Empire in Regensburg-Großprüfening . In: Yearbook of the Society for the History of Brewing. 2010, pp. 30-51.

- Karlheinz Dietz , Thomas Fischer : The Romans in Regensburg. Pustet, Regensburg 1996, ISBN 3791714848 , pp. 155-161.

- Wolfgang Eichinger, Hans Losert : A Merovingian Age fire burial site in the eastern Danube region near Großprüfening, City of Regensburg, Upper Palatinate . In: The archaeological year in Bavaria 2003, pp. 98–101.

- Jörg WE Faßbinder , Danielle Narr, Roland Linck, Thomas Deller, Florian Becker: Prospecting at the Roman fort Großprüfening, City of Regensburg, Upper Palatinate . In: The archaeological year in Bavaria , 2010 (2011), pp. 92–95.

- Michael Mackensen : A fibula grave from Regensburg-Großprüfening. To the disc brooches with bronze press plate medallions . In: Bavarian History Leaves 38, (1973), pp. 57-79.

Web links

Remarks

- ↑ a b c d e f Karlheinz Dietz , Udo Osterhaus, Sabine Rickhoff-Pauli, Konrad Spindler : Regensburg in Roman times. Regensburg 1979, ISBN 3-7917-0599-7 . P. 248.

- ↑ Lutz-Michael Dallmeier: Special excavations in the Hallstatt earthworks of Großprüfening . In: The Archaeological Year in Bavaria , 2006 (2007), pp. 59–62.

- ^ Georg Steinmetz: Regensburg in the prehistoric and Roman times . In: Georg Steinmetz, Max Heuwieser : From Regensburg's past. Ceremony for the general assembly of the general association of German history and antiquity associations in Regensburg in connection with the XVII. German archive day August 30 to September 4, 1925. Kösel & Pustet, Regensburg 1925, pp. 3–72; here: p. 28; (= Negotiations of the historical association of Upper Palatinate and Regensburg Volume 75, 1925)

- ^ A b Karlheinz Dietz , Udo Osterhaus, Sabine Rickhoff-Pauli, Konrad Spindler : Regensburg in Roman times. Regensburg 1979, ISBN 3-7917-0599-7 . P. 290.

- ↑ Annual report for the period 1909–1914 . In: Historical Association for Upper Palatinate and Regensburg. Negotiations of the Historical Association for Upper Palatinate and Regensburg , 65 (1915), p. 159.

- ^ A b c Thomas Fischer: News about the Roman Regensburg . In: Landesdenkmalamt Baden-Württemberg (Ed.): 13th International Limes Congress Aalen 1983. Lectures (= studies on the military borders of Rome 3 = research and reports on prehistory and early history in Baden-Württemberg 20). Theiss, Stuttgart 1986, ISBN 3-8062-0776-3 , pp. 146-151; here: p. 148.

- ↑ a b c Jörg WE Faßbinder , Danielle Narr, Roland Linck, Thomas Deller, Florian Becker: Prospection at the Roman fort Großprüfening, City of Regensburg, Upper Palatinate . In: The archaeological year in Bavaria , 2010 (2011), pp. 92–95; here: p. 92.

- ↑ Roman farm buildings at 49 ° 1 '2.57 " N , 12 ° 2' 19.75" O .

- ^ Sabine Rieckhoff: A Roman "brewery" from Regensburg . In: Erwin M. Ruprechtsberger (Hrsg.): Beer in antiquity . Linz 1992 (= Linz archaeological research , special issue 8), pp. 27–33; Heinrich Konen: Beer trade in the Roman Empire. Some considerations on volume, reach, and importance . In: Babett Edelmann-Singer, Heinrich Konen (ed.): Salutationes - contributions to ancient history and its discussion . Frank & Timme, Berlin 2013, ISBN 978-3-86596-471-7 , pp. 187-206; here p. 187.

- ↑ a b Thomas Fischer: Regensburg . In: Heinrich Beck , Dieter Geuenich , Heiko Steuer (Hrsg.): Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde . Volume 24, Quadriburgium - Rind, de Gruyter Berlin 2003, ISBN 3-11-017575-4 , pp. 306-317; here: pp. 314–315.

- ^ Jörg W. E. Faßbinder, Danielle Narr, Roland Linck, Thomas Deller, Florian Becker: Prospection at the Roman fort Großprüfening, City of Regensburg, Upper Palatinate . In: The archaeological year in Bavaria , 2010 (2011), pp. 92–95; here: p. 93.

- ↑ a b Jörg W. E. Faßbinder, Danielle Narr, Roland Linck, Thomas Deller, Florian Becker: Prospection at the Roman fort Großprüfening, City of Regensburg, Upper Palatinate . In: The archaeological year in Bavaria , 2010 (2011), pp. 92–95; here: p. 94.

- ^ A b Egon Schallmayer , Mario Becker: Limes . In: Heinrich Beck , Dieter Geuenich , Heiko Steuer (Hrsg.): Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde . Volume 18, Landscape Law - Loxstedt, de Gruyter Berlin 2001, ISBN 3-11-016950-9 , pp. 403-317; here: p. 424. The archaeologist Hans-Jörg Kellner determined the time of the second Alemannic attack around the year 242 from a coin hoard buried near Gunzenhausen fort , which was buried in the ground in 242 AD at the earliest, and a related find from Kösching fort / 243. The first, 233, most likely wiped out Fort Pfünz and Staubing , among others . The Köschinger find was set for the summer of 241. At that time, Emperor Gordian III ruled . (238-244). See also: Robert Roeren : On the archeology and history of Southwest Germany in the 3rd to 5th century AD In: Yearbook of the Roman-Germanic Central Museum Mainz. 7th year, Habelt, Bonn 1960, p. 217.

- ↑ a b Jörg W. E. Faßbinder, Danielle Narr, Roland Linck, Thomas Deller, Florian Becker: Prospection at the Roman fort Großprüfening, City of Regensburg, Upper Palatinate . In: The archaeological year in Bavaria , 2010 (2011), pp. 92–95; here: p. 95.

- ^ Karlheinz Dietz , Thomas Fischer : The Romans in Regensburg. Pustet, Regensburg 1996, ISBN 3791714848 , p. 182.

- ↑ Thomas Fischer: The area around the Roman Regensburg . Beck, Munich 1990, ISBN 3-406-33450-4 , plates 53, 22 and plates 54, 25

- ↑ a b Karlheinz Dietz , Thomas Fischer : The Romans in Regensburg. Pustet, Regensburg 1996, ISBN 3791714848 , pp. 155-161; here: p. 160.

- ↑ Silvia Codreanu-Windauer , Harald Gieß: The Imperial City Brunnstube . In: Die Regensburger Stadtzeitung , 7/7 (2007), p. 34; Villa Rustica at 49 ° 0 '37.54 " N , 12 ° 3' 17.55" O .

- ↑ Andreas Boos: On the early Slavic settlement of the Upper Palatinate . In: Peter Herz , Peter Schmid, Oliver Stoll : Continuities and discontinuities. From the Celtic times to the Bavarians. Frank & Timme, Berlin 2010, ISBN 978-3-86596-274-4 , pp. 123-148; here: pp. 123–125; early medieval cremations field at 49 ° 0 '52.77 " N , 12 ° 2' 20" O .