Fort Oberstimm

| Fort Oberstimm | |

|---|---|

| limes | ORL NN ( RLK ) |

| Dating (occupancy) | a) after AD 43 or before AD 61 to AD 63/68 b) around AD 80 to the Traian-Early Hadrian period |

| Type | Cohort fort |

| unit | unknown Cohors quingenaria equitata; perhaps initially the Cohors III Thracum civium Romanorum equitata to torquata |

| size | a) 132 × 108 m (= 1.43 ha) b) 1.66 ha |

| Construction | a) wood-earth b) partly stone |

| State of preservation | not preserved above ground |

| place | Upper voice |

| Geographical location | 48 ° 42 ′ 43.9 " N , 11 ° 27 ′ 18.5" E |

| height | 370 m above sea level NHN |

| Previous | Roman military camp Ingolstadt-Zuchering (Fort I) (southwest) |

| Subsequently | Eining Fort (northeast) |

| Upstream | Kastell Kösching (north) |

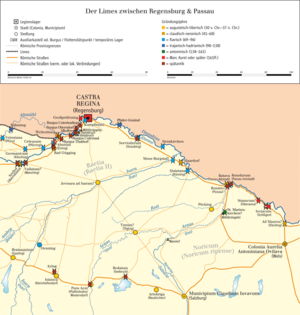

The Oberstimm fort was a Roman cohort fort near Oberstimm , a district of the Markt Manching in the district of Pfaffenhofen an der Ilm , Bavaria . The facility was initially built to secure the Danube Limes and after the border facilities were moved forward, it was increasingly used as a replenishment and supply base.

location

The settlement of the Oberstimmer area can be traced back with temporal interruptions to the Stone Age culture of the bell beakers during the end of the Neolithic . When building the fort, the Romans used the technical infrastructure already laid out by the Celts and built the facility at the intersection of two important traffic connections. One route ran on the southern lower terrace of the Danube from west to east, the other as a ford crossed the river from north to south. The western front of the garrison lay almost immediately on the southernmost branch of the Danube of the river, which was heavily branched at the time. To this day, Manchinger Strasse in the historical center of the town circumscribes the eastern and southern fronts of the fort, while Barthelmarktstrasse reflects the approximate course of the northern defenses of the garrison.

Research history

The first evidence of a Roman settlement was provided by a burial ground that was cut in 1866/1867 during the construction of the railway from Munich to Ingolstadt . As early as 1906, the Ingolstadt district doctor and medical advisor Karl Vierling suspected that a military site could have existed on a small elevation above the Barthelmarkt in Oberstimm, which was called “Auf der Wiege”. Vierling's conclusions on this were also taken up by the Barthelmarkt held annually in Oberstimm,

"Which, according to the tradition of the area, is said to have already formed a trading place between the Romans and the indigenous people and which today still has a disproportionate reputation for the importance of the small town of Oberstimm and is visited from a great distance."

Vierling was able to identify clear topographical depressions and heights around the presumed fort area and assumed on the basis of these investigations that the fortification must have been around 126 × 103/110 meters. Small re-excavations, which among other things found ceramics and brick tiles with an incised diamond pattern, confirmed the assumption. In the 19th century, rich plowed limestone material emerged from the presumed corridor. This made it possible to build a pigsty.

But it was not until the major and archeology pioneer Hermann Witz (1868–1936), with the support of the Ingolstadt Historical Society, that in 1909 succeeded in uncovering the first walls of the garrison in the “Auf der Wiege” corridor. Since the area of the Oberstimmer Fort was already partially built over before its first archaeological record, it was only possible to gain an overall impression gradually. After that, research came to a standstill for decades.

In 1955, the archaeologist Günter Ulbert dealt with the dating approach of the fort. Finds in what was then the Ingolstadt Castle Museum , now the City Museum, clearly indicated a Claudian era. The primary school principal and amateur archaeologist Josef Kneitinger worked in Oberstimm in the post-war years. He observed civil engineering work and recovered numerous finds. During his work, he also succeeded in determining the approximate course of the fort's moat and mapping it in 1961.

On the basis of this research, with the involvement of the Bavarian State Office for Monument Preservation , the scientific excavations began on the fort grounds in September 1968. The excavation technician Heinz-Jürgen Köhler was responsible as the local excavation manager. The archaeologist Hans Schönberger accompanied him scientifically . The excavations were carried out on behalf of and with funds from the Roman-Germanic Commission and the German Research Foundation . The four excavation campaigns ended in June 1971. Around 4500 square meters of the fort were uncovered. In 1982, two large halls were discovered northeast of the fortification by the archaeologist Karl Heinz Rieder , which could be interpreted as Horrea (storage structures).

In 1984 and 1985 excavations took place again. They concentrated on the plot of land at Manchinger Strasse 19, which was taken up by a farm, which covered 1,300 square meters. There, the fort area was threatened with final destruction due to the construction of a bank and residential building on its eastern fence planned for 1985. A rescue excavation was therefore officially initiated in this area, which occupied the southern part of the previously unknown Porta praetoria (main camp gate). The emergency rescues carried out in late autumn 1984 by the excavation technician Petra Summerer from the Ingolstadt excavation office of the Bavarian State Monuments Office provided important results. After the demolition of the agricultural property and the start of the excavations, the work had to be stopped due to the onset of a harsh winter, so that afterwards, under high time pressure, work could not continue until April to August 1985 in order not to endanger the schedule for the construction of the bank building. The excavations took place in cooperation with Köhler.

When the complex building conditions and ditch structures were available after an initial evaluation of the findings from the Porta praetoria, the conditions on the west side of the fort should be checked again. It is possible that the double moat now observed at the east gate had been overlooked in 1968. Therefore, from October 27 to November 7, 1986, Köhler dug a 43-meter-long search cut opposite the well-known simple ditch at the Porta decumana (rear camp gate), which ultimately confirmed the observations of 1968. However, during this search Köhler unexpectedly came across a silted-up Roman-era ship landing. There it was possible to salvage two 17-meter-long military ships, which today are among the highlights of the Celtic-Roman Museum in Manching. As a result, further investigations took place on the fort grounds from 1990 to 1992.

To the north of the cohort fort, there was also a small fort built using the wood and earth technique at an unspecified early Roman time.

Building history

Obviously the later fort area was only sparsely populated in pre-Roman times. During the excavations under Köhler, only four late Latène period ceramic shards and five others that could not be dated were found. Due to a single brick temple that was found in the castle Oberstimm, which in could Flavian period stationed there (69-96) force the Cohors III Thracum civium Romanorum equitata to torquata have been before then in the fort Künzing (Castra Quintana) was moved , where she again left brick stamps that are assigned to the period between 90 and 135. Brick stamps of the Cohors III Thracum civium Romanorum equitata from the early and middle Flavian period were also discovered in the Moos-Burgstall fort , so a stationing in this camp is also conceivable. Perhaps only one vexillation of the troops was active in different locations. The archaeologist Hans Schönberger (1916–2005) suspected that the stamp of the Thracian cohort had recently been moved to Oberstimm, as it appeared in 1929, the same year in which the first Künzinger stamps were found.

Period 1

Roman engineers probably built the facility, with its main axes exactly west-east oriented, on a natural, probably more or less rectangular, plateau-like surface as early as the 1940s of the 1st century AD. On its western flank, the terrain sloped slightly towards the valley floodplain. The Barthelmarkt festival site is located in this area today . The inner surface of the rectangular system with rounded corners (playing card shape) is 132 × 108 meters (= 1.43 hectares). The archaeologist and sigillata expert Barbara Pferdehirt saw the extensive range of potters as a sure indication that the beginning of the Roman occupation of Oberstimm, postulated by Schönberger in the 1940s, should be set after AD 43. Other, well-documented ceramics prove that it was founded at least before AD 61. Based on their considerations, the horse herdsman assumed the fort would not be built until the reign of Emperor Nero (54–68). This chronological assignment could be reconciled with the observations of the archaeologist Hans-Günther Simon (1925–1991), who stated that Oberstimm must be younger than Aislingen Castle . Schönberger contradicted Pferdehirt's view of a Neronian foundation.

Enclosure

In the west, facing the Danube, the wood-earth camp had only one circumferential trench, on all three other sides a double trench system that was connected to one another was recognizable. During the excavations from 1968 to 1971, this trench system could not be examined down to the bottom, because the groundwater that penetrated the area destroyed all attempts. The upstream inner trench belonging to Periods 1 and 2 was around ten meters wide and lay between 2.25 and 2.70 meters below the upper edge of the first subgrade. On the basis of a clearly datable, relief-decorated Terra Sigillata fragment from the Saturninus Satto pottery from Mittelbronn , which was recovered 0.30 meters above the bottom of Trench I, it was possible to prove that this trench was still in the Traianic-Early Hadrian times down to the bottom was kept open.

During the investigations of 1984 and 1985 on the eastern Porta praetoria, Summerer and Köhler were able to gain important new insights into the defense. Here the inner trench in Planum 1 was 11 meters wide and 2.60 meters deep. As already known from the older investigations on the single-lane Porta decumana in the west of the complex, the Porta praetoria of periods 1 and 2 was also recognizable as a three-phase structure. It had a double passage and was flanked by two towers that were designed as six-post construction. According to Summerer's and Köhler's findings plan, this trench did not open before the entrance to the Porta praetoria. The excavation technician was able to grasp the central posts of the gate bridge on the northern edge of the examined area.

The surrounding wall of Periods 1 and 2 that was built behind the trench was made of a wood-earth construction. The excavation from the trenches was piled between a box-shaped wooden shoring, which was held together by post positions and with the help of strong iron nails. These mostly square posts stood in ditches around 0.50 meters wide and up to 1.80 meters deep. The distances between the posts were 1.0 to 1.10 meters measured from the center. Köhler was able to examine this 3.25 meter wide wood-earth wall on the west side of the fort over a length of 31 meters. It was found that the via sagularis (Wallstrasse) , which ran in a ring around the interior of the fort, was a little more than two meters wide in this area. The berm in this section was also two meters wide. On the northern front, the Via sagularis was measured with a width of 6.5 meters. In addition to the four corner towers, intermediate towers were also built in Oberstimm in both construction periods. There was an access gate flanked by towers on all four sides of the fort.

Interior development

The interior development of the first period initially consisted of a short-term wooden construction, before the system was expanded for a Cohors quingenaria equitata , a partially mounted unit, around 500 men strong, in block construction or as a half-timbered construction . The overall structure already largely corresponded to the well-known middle-imperial scheme. Crew quarters and horse stables were grouped around the principia (staff building) and the commandant's house. Observations on the lowest remains of the half-timbered walls revealed for Oberstimm that the outside of the walls had been plastered over and whitewashed. This applied not only to the compartments, but also to the wooden stands.

In the second construction phase of the first period, the pre-Flavian principia on their east side facing the via principalis was possibly preceded by a porticus that was 2.40 meters deep . Once the visitor had passed this entrance, he stepped into a rectangular inner courtyard surrounded by a wooden porticus, which only had a room at the rear. The flag sanctuary (Sacellum) (room 1), which is located in the middle of this line, and rooms 2 and 3 to the north were the same size at 4.60 × 4.50 meters. In the area of this sanctuary with flags, the depository for the troop treasury was created as a wooden-paneled pit. There were two coins minted in the Neronian era, which can be regarded as terminus ante quem with regard to the end of the first phase of use of the fort . The archaeologist and numismatist Hans-Jörg Kellner (1920–2015) first dated both the well-preserved, lined aureus and the partly badly damaged Dupondius to the years 63/68 . According to a more recent assignment of the Neronian coins by the English numismatist Carol H. V. Sutherland (1908–1986), the aureus found just above the bottom of the earth cellar was minted around AD 64/65, while the Dupondius from around AD 66 . BC. In addition to these final coins, there were also two As coins from the reign of Emperor Tiberius (14–37) from 14/37 AD and from 22/37 AD. The archaeologist Stefan F. Pfahl suggested that the coins be included to bring a building victim in connection, because in his opinion it would have been a strange coincidence if five coins had remained unnoticed on the floor. Furthermore, he saw the two final coins in connection with the end of use of the earth cellar.

Murals

Remnants of plaster with several layers of paint come from the fort from period 1. These fragments are among the most important evidence of wall paintings in a structural military context in pre-Flavian times. As the herringbone pattern and clay residues on the back of the painting residue show, these plasters were applied to half-timbered walls. It is possible to assign the Oberstimmer paintings to different decoration systems.

The End

The period I fort remained occupied until around 68 AD at the latest. Then it seems to have been more or less completely abandoned for a short time. Unlike other early fort sites in Aislingen, courtyards and Rißtissen no burnt layer found that the in the Year of the Four Emperors could indicate 69 n. Chr. Broken unrest. Schoenberger saw in this evidence that Oberstimm no longer had a garrison at that time.

Period 2

The start of the second construction phase is indicated by a slightly worn coin that was found in a large material extraction pit in the north-western area of the fort. This means that period 2 can be assigned to the early Flavian period soon after AD 78. In 1986, in the dating approaches of individual Oberstimmer building periods, horse shepherd came to somewhat different conclusions than Schönberger, who dated the beginning of the second period to the Dominian reign (81-96) due to a singular sigil stamp . However, the renewed construction activity in other early castles of Raetia could also indicate a Flavian dating approach. There you can rely on dendrochronological data and building inscriptions. For example, a building inscription from the Kösching fort dates back to 80 AD. A dendrochronological dating also from Kösching for the year 79 AD was appropriate . Another military building inscription comes from the years 77/78 AD which was found in Günzburg . In general, the horse shepherd did not consider the strict separation of individual epochs based on the sigillate decorations in Oberstimm appropriate, as the changes in decoration were fluid.

Enclosure and interior development

During the second period, the fort's wood-earth fence kept its width of 3.25 meters. However, a general renovation took place in which almost all the posts on the outside, but only a few on the inside of the wooden casing were replaced. In 1909, Witz succeeded in uncovering the foundation walls of two connected, rectangular stone buildings. In 1919 , Friedrich Drexel (1885–1930) interpreted the eastern of these buildings as the staff building of the fort. These Principa were fundamentally very similar to the previous development in terms of the ground plan. Once again, there were no additional rooms to the north or south of the courtyard, only a rear suite of rooms was provided. Here, too, the room layout was very similar to that of the previous development and obviously had the same number of square meters. These similarities were due to the fact that the builders of the new Principia had built their stone outer foundations and the stone foundations of the rear rooms exactly over the older post pits and pits. At least the floor plans of the staff building for period 1 must have been clearly visible when construction began in period 2. In the sanctuary of the flag, which was also located in the middle of this rear row of rooms, the wood-paneled earth cellar from period 1 had to give way to a rectangular successor cellar with a square meter area made of large ashlar stones.

The End

In a final construction phase 2a, the soldiers moved the fort wall by almost 20 meters to the east, according to the considerations of Schönberger and Köhler, thereby increasing the interior of the camp from 1.43 to 1.66 hectares. Contrary to the first, different assumptions by Summerer and Köhler, the findings that were recorded in 1984 and 1985 in the area of the Porta praetoria can be corrected . The excavation technician was able to uncover traces of post positions between the inner and outer trenches, which clearly indicate a larger storage area. After the expansion, the strip was leveled with the older fort wall from periods 1 and 2. The older, three-phase Porta praetoria belonging to these periods was exactly in the same axis as the younger, single-phase successor building. This also had a double passage and was secured by two flanking towers, which were designed as six-post construction. In the area of the gate, the outer trench, which, like the inner trench, still belonged to the older expansion phase, reached a width of 11 meters in the same subgrade. However, the bottom of this trench was already reached at a depth of 1.50 meters.

The picture bowl fragment from the Saturninus Satto pottery, which was already mentioned above, was recovered from the western inner ditch, which proves that this ditch was still open to the bottom in the Traian-Early Hadrian times. A “very well preserved sesterce ” and a “almost completely freshly stamped” Dupondius from the reign of Emperor Hadrian (117-138) from AD 119/121 support this end date. Schönberger, who even before the discovery of the findings from 1984/85 argued that the outer ditch would probably also have been maintained up to this point in time and then covered, remained true even after the discovery of period 2a that the outer ditch, the this extension could have served as an obstacle to the apron, at the same time as the inner ditch was filled in in the twenties of the 2nd century. Schönberger and Koehler tried to explain this inconsistency. They assumed that, for structural reasons, the inner trench was first filled before the construction of the defense period 2a began. This thesis supports, among other things, the more sterile backfilling of this trench, which apparently also contained remains of the leveled wood-earth wall from periods 1 to 2. The backfilling of the outer trench, which logically should have been kept in a usable condition after the newly built extension, turned out to be completely different. In this trench there were mostly dark brown to gray-brown, loamy-humic deposits and a few limestone and brick fragments. In relation to the inner ditch, a much more extensive sigillate material was secured. However, no time difference in the filling of the two trenches could be ascertained from these fragments. On the contrary, the collection of sigils is the same in both enclosing trenches. It can therefore be assumed that the expansion took place shortly before the planned abandonment of the fort, which was last used mainly as a replenishment and supply base. Obviously, the military plans for Oberstimm had changed at short notice. Since the findings cannot be used to decide how long the inner trench was filled in before the outer one, an circumstantial solution to this problem remains.

Since the soil conditions in Oberstimm quickly lead to falls when wet, it can be assumed that the finds from the trenches were covered up very quickly when the trenches were no longer cleaned.

Horrea

In the early summer of 1981, unusually large buildings were recognizable in an agricultural area northeast of the Roman fort. In the autumn of the same year, in accordance with the planned land consolidation measures, the first archaeological search cuts were carried out on the presumed area. This led to the first evidence of Roman building traces. In the spring of 1982 further investigations confirmed the Roman origin of the buildings. These were built in timber and consisted of two large, three-aisled hall structures, each around 46 × 24 meters in size, facing each other with their narrow sides facing northeast and southwest. More than a third of the north-eastern building had already been disturbed by an old gravel extraction point, but it was found that both buildings had four continuous rows of twelve post pits each. The side aisles had a clear width of six meters each, the central aisles one of twelve meters each. There were six posts on each of the narrow sides. In the north-eastern building, small intermediate posts could be seen in some cases between the two-meter-deep and two-meter-wide post pits. It was possible to document that the charred remains of the posts, possibly made of oak, had a square cross-section as they rose and had an edge length of around 0.50 meters. There were several wooden fences along the building, which were supported on the sides by posts. Numerous rubbish pits were uncovered around the buildings. Numerous iron nails were found there, which could possibly come from the construction time of these hall structures. In addition, there were ceramic fragments from the early 2nd century AD and three very slightly worn bronze coins from the reigns of the emperors Domitian (81–96), Nerva (96–98) and Trajan (98–117). The size of the buildings indicates a food handling facility that far exceeded the usual needs of the Oberstimmer garrison and indicates a supraregional supply base.

In 2009, a three-aisled wooden hall construction, which was at least 38 × 18 meters in size, was cut at the Munningen fort, which was pushed across the Danube, southwest of the garrison. A dendrochronological investigation possible here showed that the up to 0.70 meter thick pine stands had been felled in late spring or early summer in 112 AD (edge of the forest). At that time, Munningen was also abandoned as a garrison location and the location was obviously rededicated for the military as a supply depot.

Ships of Mediterranean design

Not before the Late Nonic-Flavian period, dendrochronologically secured from AD 51, repeated construction work took place on the eastern bank of today's Brautlach, a tributary of the Danube. The silted up Roman-era river bed of the Brautlach, now insignificant, could be navigated by ships during antiquity. In the construction work on the bank side, rows of piles were driven into the ground along the bank. Very late dendrodata of these timbers come from the years 118, 122 and after 130 AD. When a row of stakes was erected around 92 AD - at the beginning of period 2 of the fort - the excavators suspected a bank reinforcement, but this is by no means certain.

In 1994, 50 meters west of the fort in the old river bed of the Brautlach, the wide, flat hull remains of two mid-imperial Roman patrol boats, which had been discovered in 1986 by an excavator, were recovered. The Mediterranean design is evident from the tongue and groove technique that was used to connect the planks. The two ships were found at a depth of 2.45 meters between and partly under a more recent Roman bank construction, the posts of which had partially penetrated the hulls. The dendrochronological oak examination dates the two rowing vehicles to the years 90 AD ± 10 and 102 AD ± 10 years. Since the posts of the piles driven on the bank were felled in AD 118, it has been proven that the military put both ships out of service after only a short period of operation.

Lost property

Finds from the fort and the associated facilities can be found in the Celtic-Roman Museum in Manching and in the Ingolstadt City Museum.

Monument protection

The Oberstimm fort and the facilities mentioned are protected as registered ground monuments within the meaning of the Bavarian Monument Protection Act (BayDSchG) . Investigations and targeted collection of finds are subject to authorization, accidental finds must be reported to the monument authorities.

See also

literature

Fort and other military facilities

- Stefan F. Pfahl : Golden times on the Limes. Rhaetian coin-building victims from Aalen and Oberstimm . In: Der Limes 1 (2014), pp. 32–36.

- Claus-Michael Hüssen : Militaria and work waste from the Trajan period from the Oberstimm fort, Gde. Manching, Lkr. Pfaffenhofen ad Ilm / A deer primer from the Dürnbuch forest near Münchsmünster . In: In: H.-U. Voss, P. Hammer, J. Lutz: Roman and Germanic colored and precious metal finds in comparison. Archaeometallurgical investigations based on Elbe Germanic body graves . In: Report of the Roman-Germanic Commission 79, 1998 (2000), p. 234 ff.

- Hans Schönberger , Heinz-Jürgen Köhler, Hans-Günther Simon (eds.): New results on the history of the Oberstimm fort . In: Report of the Roman-Germanic Commission 70 (1989), pp. 243-319.

- Hans Schönberger, Heinz-Jürgen Köhler, Olaf Höckmann : The eastern defense of the Oberstimm fort and ships of Mediterranean design on its western side . In: The Archaeological Year in Bavaria 1987 (1988), pp. 106-108.

- Hans Schönberger, Heinz-Jürgen Köhler, Olaf Höckmann: The eastern wall of the fort Oberstimm - ships of Mediterranean design on its western side . In: Germania 66 (1988), p. 170 ff.

- Karl-Heinz Rieder: Roman hall buildings near Oberstimm . In: Helmut Bauer: The Danube between Lech and Altmühl: past and present of a cultural landscape . Donau Kourier, Ingolstadt 1987, ISBN 3-920253-20-5 , pp. 29-30.

- Heinz-Jürgen Köhler, Petra Summerer: New findings on the eastern wall around Fort Oberstimm, Pfaffenhofen ad Ilm district, Upper Bavaria . In: The archaeological year in Bavaria 1985 (1986), pp. 99-101.

- Karl-Heinz Rieder: Roman hall buildings near Oberstimm, Manching municipality, Pfaffenhofen ad Ilm district, Upper Bavaria . In: The Archaeological Year in Bavaria 1982 (1983), pp. 101-103.

- Hans Schönberger u. a .: Oberstimm Castle. The excavations from 1968 to 1971 (= Limes research - studies on the organization of the Roman border on the Rhine and Danube 18), Mann, Berlin 1978.

- Hans Schönberger: The water supply of the Oberstimm fort . In: Germania 54 (1976), p. 403 ff.

- Hans Schönberger: The Roman fort Oberstimm. Report on the excavations from 1968 to 1971 . In: Bayerische Prognistorblätter 37 (1972), pp. 31-37; the same report also in: Archäologisches Korrespondenzblatt 2, (1972); Pp. 207-209.

- Hans Schönberger: The Roman fort Oberstimm. Report on the excavation results from 1968 to 1971 In: Ingolstädter Heimat-Blätter 34 (1971), pp. 37-40.

- Günter Ulbert : To the Claudian fort Oberstimm (district of Ingolstadt) . In: Germania 35 (1957), pp. 318-327.

- Karl Vierling: Oberstimm . In: Collective sheet of the Historisches Verein Ingolstadt 30 (1906), pp. 11-14.

Military ships

- Ronald Bockius, Wolfgang Böhler, Sylvia Cebulla, Guido Heinz, Andreas Marbs, Ellen Raskop: The Roman Age Ship Findings from Oberstimm in Bavaria (= monographs of the Römisch-Germanisches Zentralmuseum Mainz 50), Römisch-Germanisches Zentralmuseum, Mainz 2002, ISBN 978-3- 88467-068-2 .

- Albert Kremer: The salvage of the Roman ships from Oberstimm . In: Worksheets for restorers: Group 20 - Excavation technique , 30, booklet 2 (1997), pp. 325–328.

- Claus-Michael Hüssen , Karl Heinz Rieder, Holger Schaaff: The Roman ships in Oberstimm - excavation and salvage . In: The Archaeological Year in Bavaria 1994 (1995), p. 112 ff.

- Olaf Höckmann: Roman ship finds west of the Oberstimm fort . In: In: Report of the Roman-Germanic Commission 70 (1989), p. 321 ff.

Web links

- Scientific research on Oberstimm's ships . , Roman-Germanic Central Museum, www2.rgzm.de; accessed on December 11, 2016.

Remarks

- ↑ Karl-Heinz Rieder : A burial place of the bell jar from Oberstimm, Manching community, Pfaffenhofen district, Upper Bavaria . In: The Archaeological Year in Bavaria 1982 (1983), p. 40 ff; the same: Another burial place of the bell beaker culture from Oberstimm, municipality of Manching, district of Pfaffenhofen, Upper Bavaria . In: The Archaeological Year in Bavaria 1986 (1987), pp. 47–50.

- ↑ Vierling: Oberstimm . In: Collective sheet of the Historisches Verein Ingolstadt 30 (1906), pp. 11-14; here: p. 12.

- ↑ Vierling: Oberstimm . In: Collective sheet of the Historisches Verein Ingolstadt 30 (1906), pp. 11-14; here: p. 13.

- ^ Rembert Antonius Watermann: Man and medicine between power and military of the Roman imperial era . Michler, Frankfurt am Main 1980, ISBN 3-922089-10-0 , p. 21.

- ↑ Wolfgang Czysz (Ed.): Provincial Roman Research. Festschrift for Günther Ulbert on his 65th birthday . Marie Leidorf, Espelkamp 1995, ISBN 3-89646-000-5 , p. 95.

- ↑ a b c d e Hans Schönberger u. a .: Oberstimm Castle. The excavations from 1968 to 1971 (= Limes research - studies on the organization of the Roman border on the Rhine and Danube 18), Mann, Berlin 1978. p. 14.

- ^ Nils Müller-Scheeßel, Knut Rassmann, Siegmar von Schnurbein : The excavations and field research of the Roman-Germanic commission . In: Report of the Roman-Germanic Commission 82 (2001); Pp. 291-362; here: p. 344.

- ↑ a b Heinz-Jürgen Köhler, Petra Summerer: New findings on the eastern wall of the Oberstimm fort, Pfaffenhofen ad Ilm district, Upper Bavaria . In: The archaeological year in Bavaria 1985 (1986), ISBN 3-8062-04713 , pp. 99-101.

- ↑ today: Petra Zirngibl

- ↑ Hans Schönberger, Heinz-Jürgen Köhler, Olaf Höckmann: The eastern defenses of the Oberstimm fort - ships of Mediterranean design on its western side . In: Germania 66 (1988), p. 170 ff .; here p. 170.

- ↑ Hans Schönberger, Heinz-Jürgen Köhler, Olaf Höckmann: The eastern defense of the Oberstimm fort and ships of Mediterranean design on its western side, Manching municipality, Pfaffenhofen ad Ilm district, Upper Bavaria . In: The archaeological year in Bavaria 1987 (1988), ISBN 3-8062-05620 , pp. 106-108.

- ↑ a b Christina Wawrzinek: In portum navigare. Roman ports on rivers and lakes . De Gruyter, Berlin / Boston 2014, ISBN 978-3-05-009467-0 , p. 326.

- ^ Andreas Schwarcz: The becoming of the Roman Danube border . In: Andreas Schwarcz, Peter Soustal, Antoaneta Tcholakova (eds.): The Danube Limes in Late Antiquity and in the Early Middle Ages (= Miscellanea Bulgarica 22), Lit, Vienna 2016, ISBN 978-3-643-50689-4 , pp. 3– 22; here: p. 9. Oberstimm small fort at 48 ° 42 ′ 55.89 ″ N , 11 ° 27 ′ 24.73 ″ E

- ↑ Hans Schönberger u. a .: Oberstimm Castle. The excavations from 1968 to 1971. (= Limes research - studies on the organization of the Roman border on the Rhine and Danube 18), Mann, Berlin 1978. p. 136.

- ↑ Wagner 02, 00142.4

- ↑ Thomas Fischer , Erika Riedmeier-Fischer: The Roman Limes in Bavaria. Verlag Friedrich Pustet, Regensburg 2008, ISBN 978-3-7917-2120-0 , p. 180.

- ^ Nicole Lambert, Jörg Scheuerbrandt : The military diploma. Source on the Roman army and documents (= documents from the Limes Museum Aalen 55). Theiss, Stuttgart 2002, ISBN 3-8062-1726-2 , p. 54.

- ^ AE 1930, 73 .

- ↑ Wolfgang Czysz , Andrea Faber, Christof Flügel , C. Sebastian Sommer : Sites on the Danube Limes in Bavaria / Sites on the Danube Limes in Bavaria . 2006, p. 17. ( PDF )

- ^ Hans Schönberger : Moos-Burgstall. A new Roman fort In: Hans Schönberger, Hans-Jörg Kellner , Ulrich Steger, Uta von Freeden u. a .: Moos-Burgstall. A new Roman fort. Settlement of the early Urnfield and late Latène period. Cemetery from the 7th century AD and medieval complex . In: Report of the Roman-Germanic Commission 63, 1982, pp. 179–279; here: p. 214.

- ^ A b Hans Schönberger: The Roman fort Oberstimm. Report on the excavations from 1968 to 1971. In: Bayerische Prognistorblätter 37 (1972), pp. 31–37; here: p. 31.

- ↑ a b c Barbara Pferdehirt : The Roman occupation of Germania and Rhaetia from the time of Tiberius to the death of Trajan. Investigations into the chronology of southern Gaulish relief sigillata . In: Yearbook of the Roman-Germanic Central Museum Mainz , 33, (1986), pp. 221-320; here: p. 294.

- ↑ Hans Schönberger u. a .: Oberstimm Castle. The excavations from 1968 to 1971. (= Limes research - studies on the organization of the Roman border on the Rhine and Danube 18), Mann, Berlin 1978. p. 26.

- ↑ a b Hans Schönberger u. a .: Oberstimm Castle. The excavations from 1968 to 1971. (= Limes research - studies on the organization of the Roman border on the Rhine and Danube 18), Mann, Berlin 1978. p. 28.

- ↑ a b Heinz-Jürgen Köhler, Petra Summerer: New findings on the eastern fortification of Oberstimm Fort, Pfaffenhofen ad Ilm district, Upper Bavaria . In: The archaeological year in Bavaria 1985 (1986), ISBN 3-8062-04713 , pp. 99–101, here: p. 100.

- ↑ a b Hans Schönberger u. a .: Oberstimm Castle. The excavations from 1968 to 1971. (= Limes research - studies on the organization of the Roman border on the Rhine and Danube 18), Mann, Berlin 1978. p. 17.

- ↑ Wolfgang Czysz u. a .: The Romans in Bavaria . Theiss, Stuttgart 1995, ISBN 3-8062-1058-6 , p. 77.

- ^ Anne Johnson (German adaptation by Dietwulf Baatz ): Roman forts of the 1st and 2nd centuries AD in Britain and in the Germanic provinces of the Roman Empire . von Zabern, Mainz 1987, ISBN 3-8053-0868-X , p. 118.

- ↑ Hans Schönberger u. a .: Oberstimm Castle. The excavations from 1968 to 1971. (= Limes research - studies on the organization of the Roman border on the Rhine and Danube 18), Mann, Berlin 1978. p. 98.

- ↑ Hans Schönberger u. a .: Oberstimm Castle. The excavations from 1968 to 1971. (= Limes research - studies on the organization of the Roman border on the Rhine and Danube 18), Mann, Berlin 1978. p. 98.

- ^ A b Hans Schönberger , Heinz-Jürgen Köhler, Hans-Günther Simon (eds.): New results on the history of the Oberstimm fort . In: Report of the Roman-Germanic Commission 70 (1989), pp. 243-319, here: p. 300.

- ↑ Hans Schönberger u. a .: Oberstimm Castle. The excavations from 1968 to 1971. (= Limes research - studies on the organization of the Roman imperial border on the Rhine and Danube 18), Mann, Berlin 1978. p. 155.

- ^ Stefan F. Pfahl: Golden times on the Limes. Rhaetian coin-building victims from Aalen and Oberstimm . In: Der Limes 1 (2014), pp. 32–36; here: p. 36.

- ↑ Norbert Hanel : Vetera I. The finds from the Roman camps on the Fürstenberg near Xanten . (= Rheinische Ausgrabungen 35), Rheinland-Verlag, Cologne 1995; Habelt, Bonn 1995, ISBN 3-7927-1248-2 , p. 283.

- ^ Mathilde Schleiermacher: The Roman wall and ceiling paintings from the Limes fort Echzell, Wetteraukreis . In: Saalburg Jahrbuch 46 (1991), pp. 96–120; here: p. 117.

- ^ Mathilde Schleiermacher: The Roman wall and ceiling paintings from the Limes fort Echzell, Wetteraukreis . In: Saalburg Jahrbuch 46 (1991), pp. 96–120; here: p. 109.

- ↑ Kastell Burghöfe at 48 ° 38 '49.8 " N , 10 ° 49' 32.03" O

- ↑ Fort Riississen at 48 ° 16 '6.5 " N , 9 ° 50' 0.5" E

- ↑ Barbara Pferdehirt : The Roman occupation of Germania and Rhaetia from the time of Tiberius to the death of Trajan. Investigations into the chronology of southern Gaulish relief sigillata . In: Yearbook of the Roman-Germanic Central Museum Mainz , 33, (1986), pp. 221-320; here: p. 253.

- ↑ AE 1907, 00186 ; Ubi erat lupa: building inscriptions of the emperor Titus ; AE 1907, 00187

- ↑ C. Sebastian Sommer : Trajan, Hadrian, Antoninus Pius, Marc Aurel ...? - To date the systems of the Raetian Limes . In: Report of Bayerische Bodendenkmalpflege 56 (2015), pp. 321–327; here: p. 142.

- ↑ AE 1911, 00228 ; Ubi erat lupa: building inscription of a fort .

- ↑ Hans Schönberger u. a .: Oberstimm Castle. The excavations from 1968 to 1971. (= Limes research - studies on the organization of the Roman imperial border on the Rhine and Danube 18), Mann, Berlin 1978. p. 101.

- ↑ Hans Schönberger u. a .: Oberstimm Castle. The excavations from 1968 to 1971. (= Limes research - studies on the organization of the Roman border on the Rhine and Danube 18), Mann, Berlin 1978. p. 102.

- ↑ Claus-Michael Hüssen : Militaria and work waste from the Trajan period from the Oberstimm fort, Gde. Manching, Lkr. Pfaffenhofen ad Ilm / A deer brooch from the Dürnbucher forest near Münchsmünster . In: Hans-Ulrich Voss, Peter Hammer, Joachim Lutz: Roman and Germanic colored and precious metal finds in comparison. Archaeometallurgical investigations based on Elbe Germanic body graves . In: Report of the Roman-Germanic Commission, Volume 79, 1998 (2000), ISBN 3805326300 , p. 234 ff .; here: p. 235.

- ↑ Hans Schönberger, Heinz-Jürgen Köhler, Olaf Höckmann: The eastern defense of the Oberstimm fort and ships of Mediterranean design on its western side, Manching municipality, Pfaffenhofen ad Ilm district, Upper Bavaria . In: The archaeological year in Bavaria 1987 (1988), ISBN 3-8062-05620 , pp. 106-108; here: p. 106.

- ↑ Hans Schönberger, Heinz-Jürgen Köhler, Olaf Höckmann: The eastern defenses of the Oberstimm fort - ships of Mediterranean design on its western side . In: Germania 66 (1988), p. 170 ff .; here: p. 171.

- ↑ Hans Schönberger u. a .: Oberstimm Castle. The excavations from 1968 to 1971. (= Limes research - studies on the organization of the Roman imperial border on the Rhine and Danube 18), Mann, Berlin 1978. p. 147.

- ^ A b Karl-Heinz Rieder: Roman hall buildings near Oberstimm, Manching community, Pfaffenhofen ad Ilm district, Upper Bavaria . In: The Archaeological Year in Bavaria 1982 (1983), pp. 101-103; here: p. 102.

- ^ Karl-Heinz Rieder: Roman hall buildings near Oberstimm . In: Helmut Bauer: The Danube between Lech and Altmühl: past and present of a cultural landscape . Donau Kourier, Ingolstadt 1987, ISBN 3-920253-20-5 , pp. 29-30; here: p. 30.

- ^ Karl-Heinz Rieder: Roman hall buildings near Oberstimm, Manching community, Pfaffenhofen ad Ilm district, Upper Bavaria . In: The Archaeological Year in Bavaria 1982 (1983), pp. 101-103; here: p. 103.

- ↑ Kastell Munningen at 48 ° 55 '37.65 " N , 10 ° 36' 7.55" O

- ^ Friedrich Loré: Barrels and fountains. Timber conservation in the Roman vicus of Munningen . In: The archaeological year in Bavaria 2009 (2010), pp. 95–98; here: p. 95.

- ↑ Ronald Bockius, Wolfgang Böhler, Sylvia Cebulla, Guido Heinz, Andreas Marbs, Ellen Raskop: The Roman Age Ship Finds from Oberstimm in Bavaria (= monographs of the Römisch-Germanisches Zentralmuseum Mainz 50), Römisch-Germanisches Zentralmuseum, Mainz 2002, ISBN 978-3 -88467-068-2 , p. 125.

- ↑ Wolfgang Czysz (Ed.): The Romans in Bavaria . Theiss, Stuttgart 1995, ISBN 3-8062-1058-6 , p. 193.