Small fort Steinkirchen

| Small fort Steinkirchen | |

|---|---|

| limes | ORL NN ( RLK ) |

| Route (RLK) | Rhaetian Limes , Danube line |

| Dating (occupancy) | around 90 AD to a maximum of 259/260 AD |

| Type | Numerus fort? |

| size | around 58 m × 70 m (= around 0.44 ha) |

| Construction | a) wood-earth b) stone |

| State of preservation | The fort, which was largely preserved until the 20th century, has now been completely destroyed and is no longer mapped as a ground monument. |

| place | Steinkirchen (Stephansposching) |

| Geographical location | 48 ° 49 '37.2 " N , 12 ° 50' 3.8" E |

| height | 320 m above sea level NHN |

| Previous | Fortress of Straubing (northwest) |

| Subsequently | Fort Moos-Burgstall (southeast) |

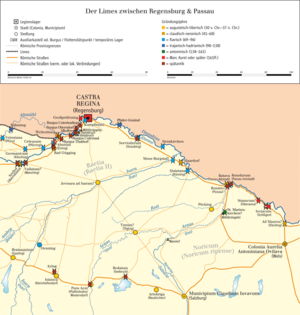

The small fort Steinkirchen was a Roman military camp that was assigned to the border guard of a section of the Raetian Danube Limes between Regensburg and Passau . The auxiliary fort was located around 250 meters west-southwest of the church of Steinkirchen and around 3.20 kilometers east of today 's Stephansposching in the Lower Bavarian district of Deggendorf .

location

Even before the arrival of the Romans, the later garrison site had been visited by people. In the area of the small fort, for example, coarse ceramic fragments were found that are probably from the Urnfield period and indicate a settlement. There was an urn burial ground around 550 meters to the southwest. A small crucible with traces of black slag and ceramics from the late Latène period, which also came to light at the site of the Roman fortification, belong to a later period .

The small fort, which is no longer visible today, was located on a flood- proof, crack-ice-age high terrace on the right bank of the Danube, directly in the bend that began to form a river loop in the area of today's town of Steinkirchen. Immediately to the north-west of the fort, the plateau fell moderately steeply sloping almost to its foot, the lower area being formed by low-terrace gravel. In Roman times, the fortification served to protect the Roman province of Raetia on the banks of the Danube. The Donausüdstraße ran a little further south past the fort. This road, coming from Regensburg, was elementary both for the relocation of troops and as a trade route and connected the Danube provinces. The course of the Danube has not changed in this area since Roman times, so that the few carefully examined findings can still provide information about the location of the garrison at that time.

Research history

The research history of the small fort begins with the work of the Catholic priest Johannes Markstaller (1875–1939), who dealt in particular with castle stables and old paths. During his research, he discovered Roman-era ceramic shards on what was then the western outskirts of Steinkirchen and assumed the actual location of the garrison only about 60 meters too far northeast of the place where the complex was finally discovered. In April 1913, Markstaller notified the General Conservatory of Art Monuments and Antiquities of Bavaria , today's Bavarian State Office for Monument Preservation, and sent some of his reading findings for examination. After the then specialist Paul Reinecke (1872-1958) had made a site visit, he denied a fort location, but considered the existence of a central imperial settlement.

The small fort remained unknown to research until 1928, even if around 1870 a gravel pit had already destroyed the north corner of the fortification without looking. The measures of the Danube regulation between Straubing and Künzing in the late 1920s also included the drainage of the floodplains and oxbow lakes , which was seen as necessary . In order to obtain material for the expansion of the flood protection dam between Steinkirchen and Fischerdorf, which has now become necessary , large amounts of gravel were required. This material could be obtained with serious interventions in the edge of the terrace towering over the Danube lowland, which resulted in further massive destruction of previously well-preserved archaeological findings. At that time, interested contemporaries perceived this destruction to be cultural depletion. The archeology-loving civil engineer Hanns Neubauer, who was responsible for the drainage measures for the Danube expansion at the time, wrote in retrospect: “In addition, there was often overexploitation, to which we can attribute that valuable finds have now been moved and are in a private collection far from Bavaria. “ Neubauer's observations and the first emergency rescues related to the small fort and the fortifications that were made there in the Middle Ages. Now that the Bavarian State Office for the Preservation of Monuments had again become known to the Bavarian State Office for the Preservation of Monuments through the local press and on advertisement, Reinecke, who had meanwhile been appointed chief curator, made another site visit in July 1928. After he was able to identify excellent cremation graves from the middle of the imperial period in particular, the building company responsible was instructed to carry out measurements and records. However, the company only inadequately met these requirements. Neubauer accused the engineer in charge of knowingly destroying the cemetery west of the fort. The State Monuments Office and the Roman-Germanic Commission tried to support Neubauer's voluntary work as much as possible and appointed him to be responsible for the maintenance of monuments in the former districts of Bogen, Deggendorf and Vilshofen. In order to be able to continue his work, Neubauer also received a small grant. Without this civil engineer with his smaller investigations and surveying work, any further knowledge about this fort would have been lost unseen through the gravel mining, as the slope terrace was moved back by 60 to 70 meters. After the extensive ground work had been completed, continued observations by Neubauer and excavations in 1929 and 1930 provided at least more precise knowledge of the southern front of the facility. In addition, a small section of the associated camp village ( vicus ) and one of the burial grounds of the garrison were recorded.

Recent archaeological excavations in 1980 have revealed several cellars and wells. A new excavation campaign was carried out in 2018, but the results obtained have not yet been published.

Building history

There is evidence that the stone-built garrison site was preceded by a wood-earth system. This first fort may have been built at the end of the 1st century or the beginning of the 2nd century. The small fort Steinkirchen had a rectangular shape with an area of around 58 × 70 meters (= 0.44 hectares). The Roman builders had pulled the north side of the facility up to the edge of the raised terrace, with the majority of its mortared stone walls being lost in the course of modern dredging work.

Enclosing wall and intermediate tower

In plan, the approximately one meter thick surrounding wall of Steinkirchen had the rounded corners typical of forts of the Principate's time and consisted of a wall shell with facing bricks between which there was cast masonry. The small fort had a berm about 1.20 meters wide and was surrounded by a pointed ditch, which was measured with a width of about 5.5 meters and a still preserved depth of about 2.60 meters. A second enclosure trench could not be observed. Apparently no trench had been dug on the north side of the garrison, where the elevated terrace sloped down towards the river. An intermediate tower built on the inside of the surrounding wall could just be found on the southwest wall. The approximately 4 × 4.5 meter tower had a wall thickness of 0.90 to one meter and did not protrude from the wall. Of the corner towers, which were only speculated but certainly existed, no construction survey was made before the destruction.

Southeast gate

The only documented gate was in the middle of the southeastern front. It had a 4.50 meter wide single-lane driveway, with two flanking gate towers, which were not quite the same size and which, at 0.90 meters, protruded almost a wall width from the connection of the surrounding wall. The western gate tower was 5.70 × 5.90 meters, the eastern 5.70 × 5.65 meters. The wide protrusion of the gate towers speaks for a relatively late expansion of the fort in stone. On the gravel fill of the ancient driveway to the gate, closer to the north-eastern gate tower, Neubauer found a total of 96 partly burned pieces of a Solnhofen limestone slab with pre-torn lines and insert holes for letters made of gilded bronze sheet, two of which were still preserved. They belonged to a building inscription once affixed above the fort gate, as it came to light in many places at Raetian fort sites. At the gate there was also a wedge made of tuff, which testified that the gate or the windows of the towers were vaulted.

The excavators assumed that this southeastern gate must have had its counterpart on the north wall in the middle of the slope front. Furthermore, two more gates in the eastern and western defenses were conjectured. It is possible that the Limesstrasse led through the last two gates mentioned. Little is known from the inside of the fort, Reinecke suspects that there was a half-timbered strip building with the team barracks and the principia (staff building) , the remains of which were lost in 1928. The finds from the fort area can be used from the beginning of the 2nd century until the time of the Alemanni invasions and the Limes falls in the 3rd century. Reinecke thought of a term ante quem up to around AD 260 and linked the apparently violent end of this fort site with the collapse of the Limes.

Camp village and cemetery fields

The camp village was, to judge by the reading finds, on the three sides of the fort facing away from the bank, in the south, south-west and east. In 1974 the upper part of a well was cut in the northeastern vicus area, at the same time cremation graves from the Middle Roman Empire were found southeast of the small fort. Archaeological investigations in the 1980s led to the discovery of several cellars and wells on today's fire station. Furthermore, indications of a Iupiter-Dolichenus temple could be found. The investigations by Neubauer had already revealed a first cremation cemetery around 150 meters from the south-western front of the small fort in a south-westerly direction. There were numerous pits with charcoal and corpse burns. Many more or less well-preserved clay vessels, including sigillates from late South Gallic, Middle Gallic and Upper Germanic manufacturers, came to light as finds. An examined grave concealed the corpse burn in a glass urn. It can thus be said that, as far as we know today , the vicus had two cremation grave fields, each of which was located on two of the roads leading out of the small fort.

Troop

Little is known about the stationed unit, with the exception of the sparse archaeological finds that indicate it. Due to the size of the troop camp, Reinicke assumed a numerus fort .

Found good

In his report from 1930, Reinecke mentioned that late South Gallic sigillata were recovered from the fort area and from the cremation cemetery . These finds could be regarded as the terminus post quem . In the "fort gate building", so most likely in the southeast gate, a coin from the reign of Emperor Hadrian (117-138) was recovered from the old excavations in 134/138 ( RIC 750). During excavations in 1980 two sigillata bowls from the 3rd century were documented. A bowl of the shape drag. 37 comes from the potter Mammilianus from Tabernae (Rheinzabern) ; After the fire, the word “ΔΟΛΟΧΗΝΟΥ” (“DOLOCHENU”) was carved into the smooth wall of the vessel in a mixed Latin-Greek form as an inscription for Iupiter Dolichenus. According to the Hungarian archaeologist and terra sigillata expert Dénes Gabler (1986), Mammilianus exported from the end of the 2nd century, more precisely from the early Severan period . The Austrian archaeologists Stefan Groh (2006) and Ute Lohner-Urban (2009) dated these goods in their more recent research between 170 and 250 AD.

Monument protection

The facilities mentioned are protected as registered ground monuments within the meaning of the Bavarian Monument Protection Act (BayDSchG) . Investigations and targeted collection of finds are subject to authorization, accidental finds must be reported to the monument authorities.

See also

literature

- Hans-Jörg Kellner (Ed.): The coins found in the Roman period in Germany, Department 1 Bavaria, Volume 2, Lower Bavaria , p. 28.

- Günther Moosbauer : The rural settlement in eastern Raetia during the Roman Empire. In: Passau university publications on archeology. Volume 4, Espelkamp 1997, pp. 251-259.

- Johannes Pätzold : Roman fort in Steinkirchen . In: Guide to prehistoric and early historical monuments 6 (1967), pp. 22-24.

- Stefan F. Pfahl : Greeks in Germania and Raetia. In: The Limes. Volume 7, 2013, Issue 1, pp. 4-6; zu Steinkirchen pp. 4–5.

- Paul Reinecke : A new fort on the Raetian Danube border (Steinkirchen, Bez.-A. Deggendorf) , Germania 14, 1930, pp. 197–205.

- Karl Schmotz: Archeology in the Deggendorf District 1979–1981. Deggendorf 1982, pp. 57-59.

- Karl Schmotz: Roman and early medieval findings from Steinkirchen, Gde. Stephansposching, Lkr. Deggendorf. In: Excavations and finds in Altbayern 1987/88. Catalog Gäubodenmuseum Straubing. Volume 13, 1988, pp. 61-63.

- Karl Schmotz: Between 1928 and 2006: The ground monuments of Steinkirchen and their fate. In: The archaeological year in Bavaria 2006. 2007, pp. 179–182.

- Karl Schmotz: Dr. Johannes Markstaller and the Roman stone churches. In: Ludwig Husty, Karl Schmotz (Hrsg.): Lectures of the 35th Niederbayerischen Archäologentag. Rahden / Westf. 2017, pp. 323–356.

Web links

Remarks

- ^ A b c Johannes Pätzold : Roman fort in Steinkirchen . In: Guide to prehistoric and early historical monuments 6 (1967), pp. 22–24; here: p. 22.

- ^ Hermann Müller-Karpe : On the urnfield settlement in the area of Steinkirchen, Lower Bavaria . In: Excavations in Germany. Funded by the German Research Foundation 1950-1975. Part 1: Prehistory, Roman times . For the exhibition in the Römisch-Germanisches Zentralmuseum zu Mainz, from May 12, 1975 to July 31, 1975 (= monographs of the Römisch-Germanisches Zentralmuseum 1), Verlag des Römisch-Germanisches Zentralmuseums, Mainz 1975, pp. 171–186; here: p. 181.

- ↑ Irene Kappel: The graphite clay from Manching . In: Werner Krämer (Ed.): Die Ausgrabungen in Manching 2, Steiner, Wiesbaden 1969; P. 49.

- ↑ Dietwulf Baatz : The Roman Limes. Archaeological excursions between the Rhine and the Danube . Mann, Berlin 1993, ISBN 3-7861-1701-2 , p. 331

- ^ Paul Reinecke: A new fort on the Raetian Danube border (Steinkirchen, Bez.-A. Deggendorf). Germania 14, 1930, pp. 197-205; here: pp. 197–198.

- ^ Karl Schmotz: Dr. Johannes Markstaller and the Roman stone churches . In: Ludwig Husty, Karl Schmotz (Hrsg.): Lectures of the 35th Niederbayerischen Archäologentag . Rahden 2017, pp. 323-356; here: p. 334 ff.

- ^ Paul Reinecke: A new fort on the Raetian Danube border (Steinkirchen, Bez.-A. Deggendorf). Germania 14, 1930, pp. 197-205; here: pp. 197-198; here: p. 198.

- ^ Karl Schmotz: Dr. Johannes Markstaller and the Roman stone churches . In: Ludwig Husty, Karl Schmotz (Hrsg.): Lectures of the 35th Niederbayerischen Archäologentag . Rahden 2017, pp. 323-356; here: p. 342.

- ^ A b Karl Schmotz: A contribution to the history of research in the Deggendorf district . In: Archaeological research in the district of Deggendorf . Special edition of the Deggendorfer Geschichtsverein for the 2nd Lower Bavarian Archaeological Day, Passau 1983, pp. 60–64; here: p. 61.

- ^ Hanns Neubauer: The Roman fort near Steinkirchen . In: Through Gäu and the forest. Sheets for home studies and home care . Supplement to Deggendorfer Donauboten and Bayerwald-Kurier No. 7, March 1954, pp. 25-26; here: p. 25.

- ↑ Andreas Boos , Karl Schmotz: Fortifications of the early and older Middle Ages in the eastern Bavarian Danube region . In: Ludwig Hust, Karl Schmotz (Eds.): Lectures of the 30th Lower Bavarian Archaeological Day, Rahden 2012, pp. 147–226; here: p. 185.

- ^ Paul Reinecke: A new fort on the Raetian Danube border (Steinkirchen, Bez.-A. Deggendorf). Germania 14, 1930, pp. 197-205; here: p. 204.

- ^ Paul Reinecke: A new fort on the Raetian Danube border (Steinkirchen, Bez.-A. Deggendorf). Germania 14, 1930, pp. 197-205; here: p. 204.

- ↑ https://www.landkreis-deggendorf.de/landkreis/kreisarchaeologie/archaeologie-in-den-gemeinden/stephansposching/roemerzeit/

- ^ A b c Paul Reinecke: A new fort on the Raetian Danube border (Steinkirchen, Bez.-A. Deggendorf). Germania 14, 1930, pp. 197-205; here: pp. 197-198; here: p. 201.

- ^ A b c Johannes Pätzold : Roman fort in Steinkirchen . In: Guide to prehistoric and early historical monuments 6 (1967), pp. 22–24; here: p. 23.

- ^ Gerhard Kaschuba: Camp gate inscriptions in the Imperium Romanum. From Claudian-Neronian to Diocletian times . University dissertation, Regensburg 1994, p. 243.

- ↑ Transcription: ------] T (?) [------ ; Epigraphic database Heidelberg

- ^ A b Paul Reinecke: A new fort on the Raetian Danube border (Steinkirchen, Bez.-A. Deggendorf). Germania 14, 1930, pp. 197-205; here: p. 199.

- ^ Paul Reinecke: A new fort on the Raetian Danube border (Steinkirchen, Bez.-A. Deggendorf). In: Germania. Volume 14, 1930, pp. 197-205.

- ^ Paul Reinecke: A new fort on the Raetian Danube border (Steinkirchen, Bez.-A. Deggendorf). Germania 14, 1930, pp. 197-205; here: p. 205.

- ^ A b Paul Reinecke: A new fort on the Raetian Danube border (Steinkirchen, Bez.-A. Deggendorf). Germania 14, 1930, pp. 197-205; here: pp. 197-198; here: p. 204.

- ^ Hanns Neubauer, short report in: Rainer Christlein : Excavations and finds in Niederbayern 1974 . In: Negotiations of the Historisches Verein für Niederbayern 100, 1974, pp. 53-107; here: p. 97.

- ↑ https://www.landkreis-deggendorf.de/landkreis/kreisarchaeologie/archaeologie-in-den-gemeinden/stephansposching/roemerzeit/

- ^ Paul Reinecke: A new fort on the Raetian Danube border (Steinkirchen, Bez.-A. Deggendorf). In: Germania. Volume 14, 1930, pp. 197-205, here pp. 203-204

- ^ Paul Reinecke: A new fort on the Raetian Danube border (Steinkirchen, Bez.-A. Deggendorf). Germania 14, 1930, pp. 197-205; here: pp. 200, 204.

- ↑ Hans-Jörg Kellner (Ed.): The coins found in the Roman era in Germany, Department 1 Bavaria, Volume 2, Lower Bavaria , p. 28.

- ^ Stefan F. Pfahl : Greeks in Germania and Raetia. In: The Limes. Volume 7, 2013, Issue 1, pp. 4-6. To Steinkirchen: pp. 4–5.

- ^ Dénes Gabler : The Sigillaten von Pfaffenhofen in Pannonia . In: Acta Archaeologica 30 (1978); Pp. 77-147; here: p. 79.

- ↑ Dénes Gabler, Andrea H. Vaday: Terra Sigillata in the Barbaricum between Pannonia and Dazien . (= Fontes Archaeologici Hungariae ), Akadémiai Kiadó, Budapest 1986, ISBN 963-05-3879-2 , p. 20.

- ^ Stefan Groh : Terra Sigillata from the excavations 2002–2005 in the vicus of Saaz . In: Helga Sedlmayer, Georg Tiefengraber (Hrsg.) :: Research in the south-east Norse vicus on the Saazkogel (Styria). The excavations of the years 2002–2005 (= Austrian Archaeological Institute, special publications 41), Austrian Archaeological Institute, Vienna 2006, ISBN 3-900305-47-1 ; Pp. 117-135; here: p. 122.

- ↑ Ute Lohner-Urban: Terra Sigillata . In: Ute Lohner-Urban (Hrsg.): Investigations in the Roman vicus of Kalsdorf near Graz. The results of the excavations on plot 421/1. Building findings and small finds (= publications by the Institute for Archeology at the Karl-Franzens University Graz 9; Research on the historical regional studies of Styria 50), Vienna 2009, ISBN 978-3-85161-018-5 , pp. 217–282; here: p. 226.