Roman military camp Ingolstadt-Zuchering (Fort I)

| Ingolstadt-Zuchering I fort | |

|---|---|

| limes | Rhaetian Limes |

| Dating (occupancy) |

late Iberian - Claudian to Trajanian |

| Type | Fort? Small fort? |

| unit | Cohort? Number? |

| size | 92 m east-west length, over 80 m north-south length |

| Construction | Wood earth |

| State of preservation | Preserved underground, visible in the aerial photo, northern area washed away by the Danube; South-east corner destroyed by railway construction |

| place | Zuchering- Seehof |

| Geographical location | 48 ° 42 '35.9 " N , 11 ° 25' 51.8" E |

| height | 368 m above sea level NHN |

| Previous | Burgus Zuchering-Seehof (west) ; Roman military camp Ingolstadt-Zuchering (temporary camps II and III) (northwest) |

| Subsequently | Fort Oberstimm (northeast) |

The Roman military camp Ingolstadt-Zuchering (Fort I) , also known as Camp I , is a former Roman garrison site that was set up as an early border post during the occupation phase of the Danube region. Located on the southern bank of the Danube, it also took on security and monitoring tasks for the river border ( Danube Limes ) . The archaeologically well-researched wood-earth warehouse is now located under an agricultural area southeast of Seehof, a district belonging to Zuchering in the district of Ingolstadt Süd in Bavaria .

location

The gravel plain in the Zuchering area was already settled in prehistoric times. Significant finds come from a Nekopole excavated in Zuchering-Ost from the Urnfield Culture and the Late Bronze Age. In Zuchering-Süd there was a settlement from the Early Bronze Age. Traces of early settlement also came to light during the excavations at the Roman camps discovered here.

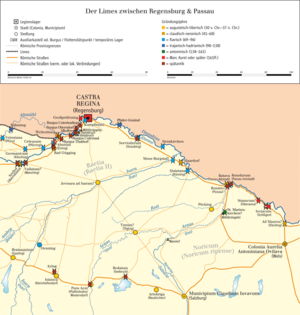

The facility in Zuchering-Seehof, built to the north of the marshy moss, was built on a largely flat terrain, probably almost at the same time as the small castles II and III near the Danube, located around 350 meters to the north-west, on a lower terrace dating from the Worm Ice Age . It is now around 4 kilometers south of the river. During antiquity, the Danube formed wide river loops in this section and shaped the border region of the Roman province of Raetia with an overflowing meadow landscape . The Sandrach , which flows by around 850 meters to the northwest , today uses the bed of a former arm of the Danube in places, which brings it very close to the Oberstimm auxiliary fort , which is around 2.5 kilometers to the east . The course of the old loop of the river at Fort I can still be seen as vegetation in aerial photographs. Oberstimm, which was occupied for a longer period of time in military terms, possibly a little later than Fort I, owned a base for the Danube fleet from AD 61 at the latest. This is also an indication of the historical proximity of the Danube to the castles on the south bank. There was obviously no danger of flooding during the 1st century AD, although Fort I with its northern part extended into the slight depression of the lower terrace. Only later did the Danube and the floods emanating from it reach the former garrison over a longer period of time and remove the northern part of the ground monument .

Research history

The Donausüdstrasse in particular became interesting for research at an early stage. In 1890, the historical association Ingolstadt acquired two bronze hairpins and two bronze spiral bracelets, which came from a sand pit on the Roman road "between the hamlet of Seehof and the village of Zuchering" . These finds, however, belonged to the Bronze Age . Roman finds from the area around the Donausüdstraße in Zuchering were already known in the past. In 1970, for example, a coin of the emperor Commodus , who ruled between 180 and 192 , came to light, which was minted in Rome in 187/188.

During a flight in the region around six kilometers south of Ingolstadt's old town, aerial photo archaeologist Otto Braasch discovered three Roman military camps southeast of Zuchering-Seehof between 1978 and 1982, as well as an adjacent section of the Donausüdstraße. The forts II and III, which were only used temporarily, were located directly next to each other and had already been half destroyed by the ongoing gravel mining in the terminal moraine landscape during their discovery . With the help of field inspections that have been carried out since the 1980s, the scientists gained an initial picture and were able to determine the duration of the facility. At the same time, the appearance of the trench was largely known from aerial photographs between 1980 and 1984. In the summer of 1992 in particular, these ditches also emerged from the ground as positive vegetation features and allowed the fort to be measured. However, only one excavation was able to clear up a number of ambiguities.

Due to construction work that led to the relocation of federal highway 16 and the parallel railway line, the south corner of the fort was to be destroyed. This led to excavations from June 25, 1992 and 1993, which were carried out by the Roman-Germanic Commission and the State Office for Monument Preservation and were under the direction of the archaeologist Claus-Michael Hüssen .

Building history

The Rhaetian Danube Valley was evidently already controlled by Roman troops from Augsburg before around AD 40. It is possible that the two temporary, short-lived north-western castles II and III, which belong to this period, were built a little earlier than Fort I. They could either come from the first exploration phase of the Danube region or existed as a construction site for the Donausüdstraße , which was probably built in the The reign of Emperor Tiberius (14–37) falls. An older section of the Donausüdstraße could be seen in front of the south gate of Fort II. The 19-meter-wide route in this area thus initially ran north of Fort I. Later, Roman engineers relocated the road a little south on a dam that had already disappeared during the excavation, directly in front of the southern trench of Camp I. counteract incipient floods in the lowland starting at Fort I. In addition to smaller, more strongly fortified wood-earth camps such as in Zuchering-Seehof and a few stations at exposed places, the Roman military command obviously did not need larger troop contingents on this section of the Danube during the Tiberian period. The Raetia of the occupation period, into which the Roman troops advanced, was often described in the past as a "barely populated" region. This impression is reinforced by the previously known small number of early garrison places. With the establishment of the Oberstimm site, the first phase of military security for this section of the Danube was completed.

The rectangular complex of Fort I had rounded corners and was oriented to the northwest with its gate-equipped flanks. The inner area of the camp was measured at 92 meters in its east-west extension, the north-south length was still around 80 meters up to the area of the washout. The former area can therefore only be estimated, but - assuming a square floor plan - could have been at least one hectare. Due to the dimensions that can only be estimated, it is not possible to determine whether Fort I in Zuchering-Seehof can be counted among the cohort forts or, as a small fort, only recorded a number .

The course of the trench surrounding the garrison could not be clarified in the northern, sanded area until 1993, even by drilling. However, it became clear that the double trench routing found in the south and south-west areas north of the two opposite gate accesses on the north-west and south-east flanks had no equivalent. There the trenches continued as a simple pointed trench. The trench stopped at the two gates. The possibility of the existence of a third entrance to the fort, which Hüssen was considering, could not be proven on the destroyed northeast flank. Likewise, no sign of another gate could be seen on the southwest side.

The outer pointed ditch was 1.70 to 1.90 meters deep and around 3.90 meters wide during the excavation. On the inside there were clear traces of an older, parallel trench, which was very steep-walled and had a deep cleaning trench. As the excavation showed, the gravelly texture of the ground at the fort was so unstable that even after brief rain showers, a lot of washed-off material collected on the bottom of the trench. Obviously the first, very steep trench hadn't taken this geological situation into account. Therefore, the side walls of the following trench were made flatter.

The inner trench runs parallel to the outer trench at a distance of around 2.20 to 2.80 meters, was 1.60 to 1.80 meters deep and 4.40 to 5 meters wide. The bottom of the trench itself was partly deeper than the outer trench. Here, too, the gravelly terrain caused rapid, natural backfilling. The second third of the trench gradually clogged the erosion after the fort was abandoned in the course of the middle imperial period. In this stratum, the excavators came across a layer of red-burnt clay interspersed with charcoal on the inside of the inner trench. Most likely these were the remains of the former turf wall and a wooden parapet that had fallen into the ditch during a fire. At that time the trenches were only visible as trough-shaped depressions.

Only with the onset of modern agricultural use of the site was the fort, which had been recognizable as a “hill”, leveled. The burnt material from the earth wall of the defense was therefore also found in the uppermost layers of the trenches, which until then were also recognizable as shallow hollows.

Since the excavation of 1992/1993 did not touch the interior of the camp, its design cannot be known more precisely. However, aerial photographs reveal some findings such as post pits. Other traces, such as a well and an almost square stone foundation with an apse, certainly did not belong to the fort and can be attributed to a more recent settlement on Donausüdstraße. It can be assumed that the soldiers of Fort I lived in light wooden barracks.

The construction of the fence indicates that there was a semi-permanent fort in Zuchering-Seehof, which was designed for a larger unit. According to Hüssen, Fort I is visually comparable with the probably simultaneous camp near Pfaffenhofen an der Zusam.

Found good

Most of the finds recovered during the excavations in 1992/1993 came from the slowly filling trenches, with the finds from the 1st century AD mainly coming to light in the middle strata. In contrast, the older gravelly floating layers directly above the bottom of the trench did not contain any remains. During the useful life of a fort, its trenches were cleaned again and again. The problem with Fort I was that there was overlap with later Roman construction work. On the one hand, maintenance measures were repeatedly carried out on the Donausüdstraße, which passed a few meters to the south, through which found material again reached the trenches that were filled in after the fort was abandoned; on the other hand, a burgus of the Danube-Iller-Rhine-Limes from which were also found in the upper layer of the trenches. These circumstances made a clear separation of the finds and their affiliation sometimes difficult. Fragments of the same late South Gallic terra sigillata picture bowl drag were found. 37 both in the fort ditch and in a nearby material pit that was used for road maintenance. Of the total of 38 coins that were recovered in 1992/1993, 35 folles were in the upper leveling layer. According to an investigation by the numismatist David Wigg-Wolf, their spectrum ranged from the years 284/299 to 354/358. In addition to the few ceramic shards from the fort trenches, there were also six varied, almost completely preserved fibulae . The finds are typical of the late Iberian-Claudian forts on the Rhaetian Danube line. An eye fibula and four recovered bronze Aucissa fibula could indicate that this fort is somewhat older than the neighboring Oberstimm fort. Aucissa Bibles are completely absent there. However, since the trenches of Fort I did not reveal any Terra Sigillata from the fort period, there were no further indications of the early chronological assignment.

In addition to the three coins recovered in 1992/1993 that did not date to late antiquity, there are also collector's finds that complete the picture:

| amount | Coin value | comment | Time position | Minting location |

| 3 | As | Tiberius for Divus Augustus - (1 × from the outer fort ditch, excavation 1992/1993) | AD 22-30 | Rome |

| 1 | As | Vespasian / Titus - from the inner fort ditch, excavation 1992/1993 | AD 69–81 | Rome / Lugdunum |

| 1 | As | Trajan - from the outer moat, excavation 1992/1993 | AD 98-102 | Rome |

| 1 | Denarius | Trajan | A.D. 103–111 | Rome |

The hinge or buckle part of a rail armor made of thin bronze sheet emerged from the ground as an important militaria find . It was found in the outer trench.

Lost property

The finds from the excavations in 1992/1993 and the coin found in 1970 are now in the Ingolstadt City Museum .

Monument protection

The fort area and the other facilities mentioned are protected as registered ground monuments within the meaning of the Bavarian Monument Protection Act (BayDSchG). Investigations and targeted collection of finds are subject to authorization, accidental finds must be reported to the monument authorities.

literature

- Claus-Michael Hüssen : The forts in Zuchering and the expansion of the Donausüdstraße. In: Late Latène and early Roman imperial times between the edge of the Alps and the Danube. Files from the colloquium in Ingolstadt on October 11 and 12, 2001. Habelt, Bonn 2004, ISBN 978-3-7749-3297-5 , pp. 74-75; here: p. 75.

- Claus-Michael Hüssen: Roman camps on the Danube in Ingolstadt-Zuchering. In: Wolfgang Czysz u. a .: Roman provincial research. Festschrift for Günter Ulbert on his 65th birthday. Leidorf, Espelkamp 1995, ISBN 3-89646-000-5 , pp. 95-110.

- Karl-Heinz Rieder: Archeology in the Ingolstadt region. In: Helmut Bauer (ed.): The Danube between Lech and Altmühl. Past and present of a cultural landscape. Exhibition catalog, Donau Courier, Ingolstadt 1987, ISBN 3-920253-20-5 , pp. 18–31.

Remarks

- ↑ a b c d e f g Claus-Michael Hüssen: Roman camps on the Danube in Ingolstadt-Zuchering. In: Wolfgang Czysz u. a .: Roman provincial research. Festschrift for Günter Ulbert on his 65th birthday. Leidorf, Espelkamp 1995, ISBN 3-89646-000-5 , pp. 95-110; here: p. 96.

- ↑ Hans Peter Uenze: News about an old find. Supplements to the grave find of Axtbrunn ("Pichl"), district of Aichach-Friedberg. In: Bavarian history sheets 75, 2010, pp. 69–86; here u. a .: p. 84.

- ↑ Fort Oberstimm at 48 ° 42 ′ 43.68 ″ N , 11 ° 27 ′ 15.55 ″ E

- ^ Xaver Ostermair: Bronze finds near Ingolstadt, Bavaria. In: News about German antiquities. 1st year, 8, 1890, p. 53.

- ↑ Josef Reichart: A Roman coin from Zuchering. In: Collection sheet of the historical association Ingolstadt. 80, 1971, p. 9.

- ^ Karl-Heinz Rieder: Archeology in the Ingolstadt region. In: Helmut Bauer (ed.): The Danube between Lech and Altmühl. Past and present of a cultural landscape. Exhibition catalog, Donau Courier, Ingolstadt 1987, ISBN 3-920253-20-5 , pp. 18–31; here: p. 28.

- ↑ a b c Claus-Michael Hüssen: Roman camps on the Danube in Ingolstadt-Zuchering. In: Wolfgang Czysz u. a .: Roman provincial research. Festschrift for Günter Ulbert on his 65th birthday. Leidorf, Espelkamp 1995, ISBN 3-89646-000-5 , pp. 95-110; here: p. 100.

- ^ Claus-Michael Hüssen: Roman settlement in the Danube valley near Ingolstadt. In: Report of the Roman-Germanic Commission , Vol. 73/1992, (1993), pp. 547-548; here: p. 547.

- ↑ a b Claus-Michael Hüssen: Settlement change and continuity in the Upper Bavarian Danube region and in the Munich gravel plain from the occupation under Augustus to the Tiberian-Claudian period. In: Late Latène and early Roman imperial times between the edge of the Alps and the Danube. Files from the colloquium in Ingolstadt on October 11 and 12, 2001. Habelt, Bonn 2004, ISBN 978-3-7749-3297-5 , pp. 73-91; here: p. 75.

- ^ A b Claus-Michael Hüssen: New research results on troop camps and rural settlements on the Danube and in the Raetian Limes area. In: Limes XVIII. Proceedings of the XVIIIth International Congress of Roman Frontier Studies held in Amman, Jordan (September 2000). BAR, Oxford 2002, pp. 535-548; here p. 537.

- ↑ a b c Claus-Michael Hüssen: Roman camps on the Danube in Ingolstadt-Zuchering. In: Wolfgang Czysz u. a .: Roman provincial research. Festschrift for Günter Ulbert on his 65th birthday. Leidorf, Espelkamp 1995, ISBN 3-89646-000-5 , pp. 95-110; here: p. 98.

- ↑ a b c d Claus-Michael Hüssen: Roman camps on the Danube in Ingolstadt-Zuchering. In: Wolfgang Czysz u. a .: Roman provincial research. Festschrift for Günter Ulbert on his 65th birthday. Leidorf, Espelkamp 1995, ISBN 3-89646-000-5 , pp. 95-110; here: p. 99.

- ↑ a b Claus-Michael Hüssen: Roman camps on the Danube in Ingolstadt-Zuchering. In: Wolfgang Czysz u. a .: Roman provincial research. Festschrift for Günter Ulbert on his 65th birthday. Leidorf, Espelkamp 1995, ISBN 3-89646-000-5 , pp. 95-110; here: p. 107.

- ↑ a b Claus-Michael Hüssen: Roman camps on the Danube in Ingolstadt-Zuchering. In: Wolfgang Czysz u. a .: Roman provincial research. Festschrift for Günter Ulbert on his 65th birthday. Leidorf, Espelkamp 1995, ISBN 3-89646-000-5 , pp. 95-110; here: p. 103.