Batavis Castle

| Fortress Passau-Altstadt | |

|---|---|

| Alternative name |

a) Batavis , b) Batava |

| limes |

a) Upper Germanic-Rhaetian Limes, Danube line , b) Danube-Iller-Rhein-Limes of Raetia II |

| Dating (occupancy) | 1st to 5th century AD |

| Type | Cohort and cavalry fort |

| unit |

a) Cohors IX Batavorum equ. mill. expl. , b) Cohors nona (nova?) Batavorum , c) Numerus Batavinus ? |

| Construction | stone |

| State of preservation | not visible above ground |

| place | Passau |

| Geographical location | 48 ° 34 '26.6 " N , 13 ° 27' 55.6" E |

| height | 300 m above sea level NHN |

| Previous | Künzing Castle (west) |

| Subsequently | Boiotro Fort (southwest) |

| Backwards | Boiodurum Fort (Passau-Innstadt / Rosenau) |

Fort Batavis (Castra Batava) is the collective name for a multi-period Roman border fort and an attached civil trade center in the area of today's old town of Passau in the administrative district of Lower Bavaria , Germany .

Due to its favorable topographical and economic geographical location on the border with free Germania, Batavis quickly developed into a regionally very important civil town and army base, which is also underlined by the construction of three forts on both sides of the Inn River up to the 2nd century AD. The Danube formed a natural protective barrier, and there was also the border between the provinces of Noricum and Raetia, marked by the Inn. The fort, located on a headland between the Danube (Danuvius) and the Inn (Aenus) , was the site of an auxiliary troop cohort ( Auxilia ) . Its crew was responsible for security and surveillance tasks on the Rhaetian Danube Limes. The name " Batavis " is derived from the troops stationed here from the Lower Germanic Batavian tribe (see also section "Garrison"). The current name "Passau" developed from it over the course of time. The decline of the Roman Empire also affected Batavis and the small fort Boiotro - on the south bank of the Inn - from the late 3rd century onwards . 470 AD, Severin von Noricum founded a monastery here. At that time, however, only the small fort and a watchtower ( " Burgus " ) in Haibach were probably occupied by soldiers. In late antique times, the place had changed into a purely civilian oppidum , which is also mentioned in Severin's vita - in connection with the withdrawal of the novels from Ufernorikum. According to the Vita, Batavis and Boiotro were destroyed by Alemanni and Thuringians between 470 and 480 and then abandoned by a large part of the provincial Roman population.

Surname

The geographer Claudius Ptolemy mentions an oppidum of the Celts , Boiodurum , d. H. the “Fortress of the Boios” or the Boier people , which can only refer to the archaeologically proven settlement of the Latène culture on the peninsula and on the banks of the Inn. The name “ Batavis ” and thus the current place name are probably derived from a Batavian auxiliary group stationed here . Batavis is also mentioned several times in Eugippius , Vita Sancti Severini .

location

Due to its location on one of the most important highways of antiquity, Boiodurum / Batavis was a traffic junction and an important trading center between East and West or between free Germania and Italy. Another road connection led via Iuvavum ( Salzburg ) to Aquileia . The earliest Roman fortification was at the mouth of the Inn and the Danube in the area of today's Passau old town . At the place of the second camp there is now St. Stephen's Cathedral . In terms of administrative law, it belonged to the province of Raetia or later the Raetia secunda and was directly subordinate to the Civitas Catenates , whose metropolis has remained unknown to date.

topography

The topography is characterized by the meeting of three rivers: the from the Eastern Alps coming Inn, which from the west flowing, while the entire southern Bavarian traversing Danube and the north of the Bavarian Forest confluent Ilz . From west to east, the Danube breaks through the primary rock of the Bohemian and Bavarian Forests and over time has formed a deeply cut valley. Exactly at this point the Inn meets the Danube stream from the south almost vertically. Before it flows into the Danube, the Inn cuts through a crystalline mountain foothill and is diverted from the direct confluence by a block of gneiss, the left high bank of the Danube. Therefore, the course of the Inn turns to the east and flows two kilometers parallel to the Danube, until the two finally unite in a 400 m wide estuary lake. Over the centuries, the Danube and Inn piled up tertiary gravel terraces with their scree. In return, the river beds have dug themselves deep into the rock layers, which mainly consist of gneiss and granite , so that in the vicinity of today's old town, very steep bank landscapes have emerged in some cases. Only the 20 meter high, wedge-shaped headland of the so-called three-river corner runs out relatively flat in the east. It forms an almost isosceles triangle, the Danube and Inn sides of which meet at the top of the village. During floods, a natural depression in the western part was flooded and established a connection between the rivers. The peninsula was completely surrounded by water. The highest point - the Domberg - was largely flood-proof. When the water was low, numerous granite cliffs protruded from the river from today's Vilshofen to the mouth of the Ilz, which hindered shipping and created dangerous eddies. The last such obstacle, the Schusterstein, could only be removed by demolition in 1907. The Danube and Inn thus protected the peninsula on its north, east and south sides. Access from the land side, in the west, could also be blocked with little effort.

function

As in the previous millennia, the Celts of the late Latène period played a decisive role in the favorable economic and geographic location of the river island for the establishment of the somewhat larger oppidum Boiodurum . The subsequent Roman Boiodurum / Batavis was the gateway to the provinces Ratia (Raetia) and Noricum (Norikum) and at the same time the border between the Gallic and Illyrian customs districts

- quadragesima Galliarum or

- publicum portorii Illyrici .

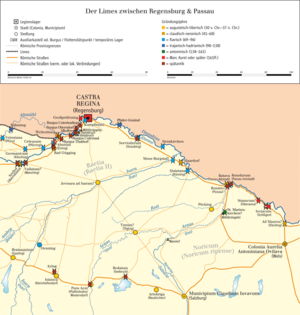

The forts on the north bank of the Inn were part of the Rhaetian Limes. The tasks of the crew probably included securing the river border (ripa) and the Inn crossing from the Roman province of Raetia to Noricum , collecting customs duties, transmitting communications along the Limes and monitoring and controlling the road connections. The traffic on the rivers and the Limes Road (via iuxta Danuvium) could be effectively controlled from here and the goods of merchants passing through could be declared to be stacked goods . The Bavarian Forest and the Bohemian Forest formed a densely wooded and inaccessible barrier. It was therefore unlikely that invaders would invade from the north. Attacks were more likely to be feared along the rivers. In order to be prepared for this, river warships patrolled the Danube constantly. In addition, a security line was set up consisting of watchtowers and forts, which were connected to one another by the Limes Road, and with which the border could be monitored to some extent.

Research history

Finds from the Stone Age have been recovered in the urban area (stone ax, stone hoe), the Toompea itself may have been surrounded by a ring wall early on , which was destroyed several times, but rebuilt again and again. Its traces can be traced back to the La Tène period .

Research into the ancient remains of the fort and settlement in the old town area began with collecting random finds in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Between 1918 and 1919 Paul Reinecke examined the remains of the so-called "Roman Defense" in the seminar garden of St. Stephan. In the 1920s, an ancient reliquary container was discovered in the church of St. Severin in the Innstadt district of Passau , but was not recognized as such. Since then he has been considered lost.

Only after the Second World War did research activities in connection with Batavis experience a noticeable upswing. In 1976 Walter Sage uncovered a late antique sacred building in the Church of St. Severin , which probably dates from the time of Severin von Norikum. In 1978, during excavations by the Bavarian State Office for Monument Preservation , Rainer Christlein was able to locate the late antique fort and the civil settlement in the area of the monastery church "Zum Heiligen Kreuz" and the Niedernburg monastery . It was found that the earliest church building, possibly only around 700, was built directly on the ruins of the late antique fort. The more than 1000 recovered Roman coins mostly come from the eastern provinces of the Roman Empire. In 1981, during dredging from the Inn, tombstones from the middle of the imperial period came to light, which were presumably inserted into the defensive wall as spoils . This was also an indication that its southern section could once have plunged into the river due to continuous undercutting.

development

Pre-Roman times

The settlement of the place probably started from the Bronze Age (2000 to 1000 BC). Around 400 BC The Celts immigrated to the region around Passau and also founded a settlement here. During the Hallstatt period (1000 to 500 BC) there was lively trade here with the south and Italy ( Etruria ). Waterways were mainly used for the transport of commercial goods. An old mule track, known today as the “path through the forest”, along the Ilz and Erlau rivers, was probably already in use at that time. The late Celtic settlement stretched from the Niedernburg monastery to the cattle market; its port was located at the height of today's old town hall. The Celtic oppidum was abandoned around 100 years before the arrival of the Romans.

1st to 2nd century

During their advance to the north, the Romans immediately recognized the great strategic importance of this three-river valley. The Inn formed the border between the two provinces of Raetia and Noricum. It is possible that a fortified customs post was established under Emperor Claudius around 50 AD in the area of the Niedernburg monastery, which took over the Celtic place name Boiodurum . A residential and commercial area and a Danube port (today Römerplatz) developed in the vicinity. On the Noric banks of the Inn, under Emperor Domitian around 90 AD, instead of an earlier Celtic settlement, a fortification was built using wood and earth technology, the Boiodurum fort . During the early and middle imperial period, the military character of this place was predominant, as one suspects on the basis of numerous onion button fibulae that have been found. With the establishment of the Upper German-Rhaetian Limes , a secure and continuous connection between the western and eastern halves of the empire could be established. The entire length of the Danube was now under Roman control, which is why the army also moved its border security in the Passau area from the Inn to the Danube. Therefore, intensive shipping and trade soon developed on both rivers. Two forts existed one after the other on the Rhaetian side. Probably during the reign of Emperor Nero (54–68 AD), the first fort was built near the eastern tip of the peninsula, which was probably used primarily to monitor shipping traffic and collect customs duties. The neighboring tribes in Magna Germania (the "free" Germania), the Hermundurs and Narists, behaved relatively quietly for a long time. B. Access to the markets of the Rhaetian provincial capital Augusta Vindelicorum was also allowed.

At that time there was already a well-developed Roman road along the southern bank of the Danube, which could be used to get to the east of the empire as far as the Black Sea . The closest legion camps and larger settlements were Castra Regina (Regensburg) in the west and Lauriacum (Lorch below Enns) down the Danube. The Rhaetian customs station was converted into a permanent fort around the year 100. From the 2nd century, weir ditches and stone enclosing walls have been documented for the fort. Before that, a camp village ( vicus ) spread out. With the stationing of the Cohors IX Batavorum around 160/170, a new, larger camp was necessary that could accommodate the troops of up to 1000 men. The new fort, known according to the sources as Castra Batava or ad Batavos , was probably located between Spitzberg and Toomberg . However, conclusive archaeological finds could not be made there. In the course of the catastrophic events of the Marcomann Wars (AD 166–180), the Neron fortifications on the eastern tip were probably destroyed and had to be abandoned. The vicus (camp village) of the abandoned Neronian fort could now also expand to the west because of the leveling of the old ditches. During the 2nd and first half of the 3rd century, a town-like settlement, Batavis , emerged on the peninsula and became a regional shipping, traffic and trading center. Despite its strategically favorable location at the intersection of important long-distance traffic and trade connections, Batavis was not granted any higher legal status ( municipium or colonia ) in the course of its existence . The civil camp villages also profited massively from the Pax Romana , a 250-year period of peace. A heated bathing facility in Boiodurum offered greater comfort . Small statues of gods, such as the bronze statuettes of the state god Jupiter and the goddess of victory Victoria, found in the old town area, attest to the practice of the gods cults that predominated in the Roman Empire. The gravestone of the wine merchant Publius Tenatius Essimus from Tridentum ( Trient ) is proof of extensive trade connections . He imported Italian wine and shipped it over the Inn and Danube to Aquincum (Budapest). Fine handicrafts such as gems and women's jewelry suggest a modest wealth of the population.

3rd to 4th century

As a result of its destruction by the Alemanni incursions between 260 and 270 AD, the camp on Domberg was abandoned. From 280 onwards, military activities were again concentrated on the eastern end of the peninsula. For this purpose, a new fortification was built on the rubble of the Middle Imperial period vicus . It was probably a walled, city-like settlement. One of its sections may have been solidly fortified with a remnant fort. The place name Batavis was retained. The Boiodurum fort was also given up. The border defense of the Danube Limes was fundamentally reorganized and consolidated after 280 under the emperors Diocletian , Maximian , Constantine I and Valentinian I. In place of open settlements and the square forts from the Middle Imperial period, smaller but much heavier fortified structures were built. At the end of the 3rd century, the border security was taken over by the crews of the small fort Boiotro and the Burgus Passau-Haibach . The former stood as a new military center on the Norse side directly on the banks of the Inn. The bulwark secured a settlement of the same name with a boat landing and a ferry connection to the Rhaetian bank. Coin and pottery findings suggest that Boiotro was evacuated by the regular military around 400. Presumably his garrison withdrew to the more defensible Batavis . With the withdrawal or the rapidly advancing dissolution of the Western Roman army in the early 5th century, Batavis also lost its military function and turned into a purely civilian oppidum . At that time, because of the precarious security situation, the villae rusticae in the open countryside and the unfortified cities and settlements also depopulated . The survivors of the Romanesque population had to seek protection behind solid walls. Since the number of regular troops had already drastically decreased, they mostly found them in the former forts.

5th to 10th century

After it was tolerated by Emperor Constantine (324–337), Christianity seems to have established itself in the provinces of Raetia and Noricum as early as the end of the 4th century. After the death of the Hun ruler Attila in 453, Severin came from Noricum via Pannonia (Pannonia) to Noricum ripense (Ufernoricum), whose hard-pressed population at that time had to contend with the effects of the collapse of the Western Roman Empire and the great migration . He met a Roman provincial population Christianized for several generations and also tried to convince the Germanic tribes living across the Danube to accept Christianity. Severin stayed mainly in the Danube Valley between Carnuntum in the Vienna Basin and the area around Passau. In Batavis he found a Roman occupation and reports that merchant shipping and agriculture continued. In Boiotro and Batavis there were churches that were looked after by monastic communities. Due to his good contacts with the barbarian rulers, Severin soon became an indispensable advocate and advisor of the Romans and often negotiated successfully with local Germanic princes in order to prevent attacks on cities or to release prisoners again.

The Severin's vita of Eugippius, written around 511, handed down a. a. also the names of some Romanesque villages on the upper Danube that Severin visited on his hikes through the provinces of Noricum ripense and Raetia secunda . Batavis is described as a town-like settlement (oppidum) between Inn and Danube (… inter utraque flumina Aenum atque Danuvium…) and as surrounded by solid walls (… extra muros oppidi Batavini…) . Obviously it also had a small regular guard. Together with Christianity, a tightly managed church organization and infrastructure quickly established itself, which ultimately also took over the tasks of the crumbling western Roman administration. In Batavis, Severin found an evidently well-functioning ecclesiastical administration with officials such as presbyters , deacons , monks and even a singer who were in the service of a bishop. The names of a presbyter, Lucillius, and a deacon, Amantius, have also been handed down for Batavis . In the early 5th century, a peristyle-like building with a courtyard surrounded by columns was built in the area of the church "Zum Heiligen Kreuz" . Later the first church of the Christian community of Batavis was built there , a 19 × 14 meter hall church with an apse (early to middle 5th century). Severin is intended here, subsequently, a monastery with a church, baptistery ( baptistery ) , which probably stood at Innufer, have established some monks (... cellulam paucis monachis fundaverat ...) . The basilica in Boiotro , which Severin and Eugippius mentioned and consecrated to John the Baptist, was almost certainly the predecessor of today's Severinskirche. The cella with baptistery in Batavis , also mentioned in the vita, is believed to be near Niedernburg or on the Domberg. An archaeological reference to the Severinskloster could be an installation from this time in the abandoned Boiotro Fort . Trade is also likely to have been of greater importance, as the townspeople asked Severin to intercede for them with the Rugier king Feletheus because of a trade permit.

Batavis himself was under constant threat from the Alamanni. Because of their ongoing attacks, the residents asked Severin to visit their city and act moderately on its king Gibuld , who had great respect for him. As soon as the latter appeared with his warriors in front of the city, Severin met Gibuld for an interview. He and a middleman, the deacon Amantius, were not only able to persuade him to withdraw, but also to bring 70 novels back to the city - previously set by the Alemanni. The priest ( presbyter ) Lucillius later achieved another similar success.

Due to the increasing danger of Teutons, the novels from Quintanis were the first to give up their settlement - on the urgent advice of Severin - and initially fled to Batavis from where they were to be taken to a reception camp in the still reasonably safe Lauriacum ( Enns ). Thereupon the Alamanni besieged Batavis in the hope of being able to plunder the population of two cities. However, the storm on the city could be repelled again. Despite Severin's urging to give up their homeland and move with him to Lauriacum, their citizens could not be induced to do so and instead asked him to leave the city. The oppidum was finally - as predicted by Severin - sacked around 476 in an attack by the West Germanic Thuringian tribe under their leader Hunumund. Its inhabitants were massacred or taken away as slaves. As the excavations showed, however, it is unlikely to have been completely destroyed, as a continuity of settlement could be proven beyond this catastrophe. For Passau this did not necessarily mean the end of Roman culture. Some of the Romanized inhabitants persisted here and the Teutons were partly already Christianized and took over some Roman traditions. The city was also the seat of a bishop well into the 6th century. Remnants of the Roman wall probably also protected the early medieval town of Bazzawe until it was demolished in 977 on the orders of Emperor Otto II .

Castles

| 3D reconstructions of the forts in Passau |

|---|

| ArcTron 3D , 2013 |

| Multimedia film production |

|

Link to the picture |

In ancient times, three forts were built in the area around Passau's old town:

- a Claudian / Neronian or late Flavian camp (Fort I or customs station),

- an Antonine camp (Castle II Castra Batava or ad Batavos ) and

- the late antique camp (Kastell III or Oppidum Batavis ).

Fort I: The early camp was founded around 50 AD. Its location probably extended to the area of Kloster Niedernburg -Römerplatz-Bräugasse. It was probably initially surrounded by three moats. At the end of the 1st century AD it was expanded a bit and secured in the west by five weir ditches. The location of a gate is also known. Only very few traces of its interior structures have been found because of the dense modern building. The trenches of the camp were apparently filled in again later. At today's Prinzregent Luitpold Bridge (suspension bridge) there was still a section of a two-meter-deep and five-meter-wide ditch that stretched to the Niedernburg monastery and then on to the Danube. The excavator, Susanne Arnold, assumes that he also belonged to this camp.

Fort II: This camp was built around 140 to 180 AD on the plateau between Spitzberg and Domberg - probably in the area of Nikolastraße and the parade ground. A wall foundation about two meters wide in the east of the parade ground, discovered in 1908, is its only known remnant.

Fort III: After the destruction of Fort II around 270 AD, a new fort was built near the top of the village. This was left to the civilian population as a settlement site in the early 5th century. Remains of the late antiquity fortifications have so far been proven on the basis of spoilage from the Inn; most of this wall section probably fell into the river in the Middle Ages.

Roman Defense

This wall, the remains of which can be traced on the south side of the Domberg from the parish church of St. Paul to Schwesterngasse, was made of granite and gneiss and originally also had a battlement covered by a crenellated wreath. It was not until the early 19th century that this wall - previously only known as "Wehre" (Joseph Lenz, 1819) - had the misleading name "Römerwehr" (creation by Adam Joseph Freiherr von Mulzer, from 1829). During a re-excavation in the seminar garden of St. Stephan, carried out by the Passau City Archeology, the results of Paul Reinecke's excavation in the early 20th century were checked using modern research methods. The fortification, which Reinecke viewed as a Bavarian rampart on late Roman foundations, is in fact likely to date from the turn of the 9th to the 10th century and was destroyed in the war of 977 between Emperor Otto II and Duke Heinrich the Quarrel . This dating could not be fully verified by the accompanying finds, however, the construction of the wall is strongly reminiscent of other fortifications of the same period, such as an identical copy in Roßthal . The previous wall, which Reinecke still referred to as late antiquity, is therefore likely to have actually belonged to the early medieval fortification of the cathedral district.

garrison

The following units are known to occupy the forts or could be considered:

| Time position | Troop name | comment | Illustration |

| 1st century | Auxiliary Cohort? | The occupation force of the early fort is unknown. | |

| 2nd to 3rd century | Cohors nona Batavorum equitata millaria exploratorum (the ninth, partially mounted cohort of Batavian scouts) | When it was moved to Passau is a matter of dispute; it can be demonstrated on military diplomas in Raetia since 147 and is in Batavis until the early 5th century. This unit, which can be traced here from 160/170 AD and consists of around 1000 men (including 200 riders), originally came from the Lower Rhine . Dietwulf Baatz also identified them as the regular troops for Ruffenhofen Castle , and they may also have been located in Weissenburg Castle for a while. There she was stationed in the so-called east fort, which only existed for a short time and was evacuated no later than 125 AD. The troops were probably moved to Batavis during the preparations for the invasion of the Marcomanni area under Emperor Marc Aurel . |

Equipment of an auxiliary soldier in the 3rd century (figurine in Kastell Saalburg )

|

| 3rd to 5th century? | Cohortis nonae (nova?) Batavorum (the ninth / new? Cohort of the Batavians) | The Batavian cohort and the rank of its commanding officer ( tribunus ) also appear in the late antique Notitia dignitatum , in the troop list of the Dux Raetiae , under their old serial number. Rupert Aign, however, suspects that the troop was reorganized as in the 4th century AD ( cohors nova ). | |

| 4th to 5th century? | Numerus Batavinus (a host of Batavians) | From the Bataverkohorte of went into the final phase oppidum possibly the - mentioned in the Severin Vita - Number forth (... militares turmae sunt cum deletae limite, Batavino utcumque numero perdurante ...) , probably a 40-50-strong guard unit ( vigiles ). Presumably it consisted of scattered limits and newly acquired novels . Material finds indicate that among them were soldiers of Germanic origin. The presence of such a unit in this region is otherwise only known from the discovery of a few brick stamps in the Upper Austrian part of the Danube Limes. However, their assignment is still controversial today. It appears that, despite the dissolution of the border guards in the early to mid-5th century, they continued to hold out in their garrison. Possibly this number was in a separate internal or residual fort within the city walls, since the Boiotro fort on the opposite, Noric bank of the Inn - after evaluating the findings made so far - was no longer occupied by the regular military in the late 5th century. According to a passage in Severin's vita, the soldiers, who were probably paid for their service mainly in kind, decided to march a detachment to Italy to claim the long overdue pay (extremum stipendium) . On the way there, however, she was ambushed by the enemy and cut down to the last man. The rest of the force later came to an end when the city was stormed by Hunumund. |

Numerus brick stamp from Linz , probably burned in Passau

|

Civil settlements

Traces of commercially used, wooden strip houses of the vicus , which was roughly the same size as the late Celtic oppidum , could be found on the slightly lower terrace around the church "Zum Heiligen Kreuz" in the Niedernburg monastery (approx. 200 AD). . The evaluation of the find stretches and the mapping of the finds resulted in an east-west expansion of the settlement to a length of around 1250 meters. At the branch church of St. John the Baptist , the hospital church of the St. John Hospital on the Rindermarkt , an ancient burial ground ( cremation graves ) was found. A transition over the Inn to Boiotro Fort was probably in the area of today's Augustinergasse or Innstrasse.

The late antique, only 200 × 150 meter large oppidum had been significantly reduced in size compared to the mid-imperial vicus . In the north, east and south, the wall was surrounded by water. In the west, a massive transverse wall was built that separated the late Roman settlement from the - now completely deserted vicus - and from the interior. Coins and small finds (ceramics) prove that the settlement was inhabited in the 4th and 5th centuries by a mixed population of Roman and Germanic tribes (civilians, traders and soldiers). The very simple houses consisted mainly of wood and half-timbered structures that were placed on narrow stone foundations. Basement basements, as they sometimes still existed in mid-imperial buildings, could not be discovered. The remains of an early Christian, 27 × 13.5 meter large hall church with apse and vestibule, which was connected to other buildings, were found under the church "Zum Heiligen Kreuz" in Niedernburg Abbey. According to Walter Sage, it could be the church of the monastery built by Severin in the 5th century. One mentioned in the Vita baptistery ( baptistery ) could not be detected archaeologically so far. To the east of the town hall square there was probably a port facility.

economy

The inhabitants of the Celtic oppidum probably mainly operated agriculture, but also traded in graphite (for the production of fire-proof pots) from Kropfmühl and salt . Otherwise, because of the course of the rivers - and also the lack of sufficient usable arable land in the immediate vicinity - the settlers were dependent on shipping to make a living. The favorable traffic situation allowed a market place to emerge here in pre-Roman times. At that time, most of the transport of goods was carried out by water, as this was significantly cheaper and easier than transport by carts. In addition, larger quantities of goods could be shipped in a relatively short period of time - especially downriver. However, shipping against the current was also possible by towing . With its favorable location on three rivers, Passau has always played an important role as a goods transshipment point. The Inn rises in the Swiss Alps , at that time in the middle of the Roman Empire, it runs to the northeast and thus functioned as an inner-Roman north-south connection, via which a smooth exchange of goods between the provinces could be carried out. He also marked the customs border. The Ilz was also a north-south connection, but not in the Roman sphere of influence as the river ran through the Barbaricum without exception. Due to its small size, its course through the Bavarian Forest and the mostly tense relationship with the Germanic tribes, it was used less as a trade route. However, it cannot be ruled out that at least larger amounts of wood were transported across the Ilz, as there was a shortage here due to massive clearing in the Roman territory. The Danube runs from west to east. It is many times longer than the other two rivers and, from Passau, also much wider. The river flows into the Black Sea and was an elementary part of the Roman economy, in addition it represented an east-west connection across cultures. The local craftsmen were mainly active in iron processing, glass production and the pottery industry. In the early imperial era, the craft in the vicus developed based on the Roman model. The small finds, knife blades, a pair of pliers, an iron four-pointed ( crow's foot ), etc. a. close to an iron processing workshop. Evidence for the stonemasonry workshops - presumably located in the village itself - is a consecration altar for the god Hercules Augustus found in 1980 in "Parzgasse 3" and - later used as a baptismal font in the church of St. Severin - the gravestone of the customs officer Faustinianus. The inscription stone from the Trientine wine merchant Publius Tenatius Essimus, which was excavated in 1981 near the Schaibling Tower, is of high quality craftsmanship and was originally part of his elaborately designed tomb and was probably used for the city wall in late antiquity. It is also evidence of the apparently very profitable wine trade between Raetia / Noricum , Barbaricum and Italia at the time . Mainly wine from Northern Italy, sigillate crockery from the Rhineland and glass from Pannonia were transported on the Roman Limes Road . Large quantities of the coveted salt continued to come to the Danube from the deposits in the Alps. Wine and salt were presumably negotiated from here to the Bohemian region. Occurrences of clay to the west of the city and at the foot of the Oberhaus fortress also made it possible to manufacture bricks on site.

population

The population consisted of a smaller upper class of indigenous Romans (troop commanders, officers) and a broader middle class of soldiers from all parts of the empire. At the end of their service, they were granted Roman citizenship and then married mostly local women. In the course of time, traders, boatmen, craftsmen, and innkeepers were added - they were the descendants of the Celtic indigenous people and immigrants from Italy or other Roman provinces. They communicated with one another using the official and cultural language of Latin, which was predominant in the empire, and were loyal to the Roman Empire. With the constitutio Antoniana under Caracalla (212), all free Provençals were finally declared Roman citizens. In late antiquity (end of the 5th century), Germanic elements - as auxiliary troops and allies - increasingly gained influence in the provincial Roman population.

Monument protection, notices

Batavis Castle and the facilities mentioned are protected as registered ground monuments within the meaning of the Bavarian Monument Protection Act. Investigations and targeted collection of finds are subject to approval, random finds must be reported to the monument authorities. Due to the dense medieval and modern development, no above-ground Roman remains have been preserved on Domberg, Niedernburg Abbey and Dreiflusseck. In memory of the Roman Danube harbor and the fort settlement, the open space in front of the suspension bridge was named "Römerplatz".

literature

- Helmut Bender: Passau. In: Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde (RGA). 2nd Edition. Volume 22, Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2003, ISBN 3-11-017351-4 , pp. 496-499. ( Excerpt in the Google book search)

- Announcements from the Society for Regional Studies in Salzburg. 122nd year of the association, Salzburg 1982, self-published, p. 62.

- Rainer Christlein: The late Roman Batavis fort under the Niedernburg monastery church in Passau, Lower Bavaria . In: Severin between Roman times and the Great Migration . Exhibition catalog, Enns 1982, pp. 507–509.

- Hannsjörg Ubl : The archaeological research of the Severin variety and the end of the Roman era in the Danube-Alpine region . In: Severin between Roman times and the Great Migration . Exhibition catalog, Enns 1982, pp. 507–509.

- Erich Widder : patron saint St. Severin. A contribution to patronage and the history of the veneration of Severin . In: Severin between Roman times and the Great Migration . Exhibition catalog, Enns 1982, pp. 43–55.

- Günther Dembski : Coin minting and circulation in the Danube region of the 5th century . In: Severin between Roman times and the Great Migration . Exhibition catalog, Enns 1982, pp. 201–215.

- Thomas Fischer, Erika Riedmeier-Fischer: The Roman Limes in Bavaria . Verlag Friedrich Pustet, Regensburg 2008, ISBN 978-3-7917-2120-0 , pp. 194-196.

- Jörg-Peter Niemeier (ed.): Passau - part of the Roman Empire. Guide through the Roman museum Kastell Boiotro , Passau 2014 ( ISBN 978-3-929350-91-3 ).

- Wolfgang Maria Schmidt: Illustrated history of the city of Passau. Ablaßmayer & Peninger, Passau 1927, pp. 5–20.

- Herbert Schindler: Passau. Guide to the art monuments of the three-river city. Passavia, Passau 1990, ISBN 3-87616-143-6 , pp. 13-21.

- Rudolf Zinnhobler , Erich Widder: The holy Severin - His life and his admiration , 2nd, supplemented edition, Museumsverein Künzing, Verlag Josef Duschl, 2004, ISBN 3-933047-71-4 , pp. 36-37.

- Michael W. Weithmann: Passau Small City History , 2nd revised and updated edition, Verlag Friedrich Pustet, Regensburg 2014, ISBN 978-3-7917-6017-9 .

Remarks

- ↑ Geographica 4, 16-23.

- ↑ XIX 1, Batavis appellatur oppidum inter utraque flumina, Henum videlicet atque Danuvium, constitutum. XXII 4. XXIV 1. XXVII 1, oppidum Batavinum, XXII 1, limes Batavinus, XX 1; the inhabitants: Batavini, XXVII 3.

- ↑ Herbert Schindler: 1990, p. 15.

- ↑ Wolfgang M. Schmid: 1927, p. 5, Michael W. Weithmann, 2014.

- ↑ Wolfgang M. Schmidt: 1927, p. 9.

- ^ Paul Reinecke: Excavations on the old town hill in Passau. In: Germania. 3, 1919, p. 57 ff.

- ↑ Erich Widder: 1982, p. 43.

- ↑ Helmut Bender: Passau. In: Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde (RGA). 2nd Edition. Volume 22, Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2003, ISBN 3-11-017351-4 , pp. 496-499.

- ^ Announcements of the Society for Salzburg Regional Studies , 1982, p. 62.

- ↑ Walter M. Schmidt: 1927, p. 12.

- ↑ Herbert Schindler: 1990, p. 13.

- ↑ Michael W. Weithmann 2014

- ↑ Rainer Christlein: The archaeological year in Bavaria , 1980, p. 126, Michael W. Weithmann 2014

- ↑ See also Edward A. Thompson : Romans and Barbarians . Madison 1982, pp. 113 ff. ( The End of Noricum ).

- ^ Vita Severini: Chapters 19, 20, 22, 24, 27, Rudolf Zinnhobler: 2004, p. 36.

- ↑ Rudolf Zinnhobler: 2004, p. 37.

- ↑ Rainer Christlein: 1982, p. 508, Hannsjörg Ubl: 1982, p. 82 and 566

- ↑ Walter M. Schmidt: 1927, p. 17.

- ↑ Walter M. Schmidt: 1927, p. 16.

- ^ Heinz Kellermann: City moat, city wall, towers and gates between Passau and St. Nikola. Passau 2002, p. 9; Herbert Schindler: 1990, p. 13.

- ↑ distress. dign. Occ. 35, 24: “a tribune of the 9th Batavian cohort in Batavis”.

- ↑ Herbert Schindler: 1990, p. 17.

- ↑ Rudolf Zinnhobler: 2004, p. 37.

- ↑ Thomas Fischer, Erika Riedmeier Fischer: 2008, pp. 194–196.

- ↑ (Eugippius: Chap. 20/1) Günther Dembski: 1982, p. 209.

- ↑ Herbert Schindler: 1990, p. 17.

- ↑ Erich Widder: 1982, p. 43.

- ↑ Hannsjörg Ubl: 1982, p. 82.

- ↑ Herbert Schindler: 1990, p. 14.

- ↑ Walter M. Schmidt: 1927, pp. 9-11, Herbert Schindler: 1990, p. 17.