Osterhofen-Haardorf small fort

| Osterhofen-Haardorf small fort | |

|---|---|

| Alternative name | Haardorf-Mühlberg, Haardorf-Mühlham |

| limes | ORL NN ( RLK ) |

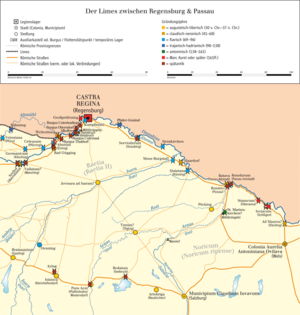

| Route (RLK) | Rhaetian Limes , Danube line |

| Dating (occupancy) | Claudian |

| Type | Small fort |

| size | a) Outer circumference: around 55 × 55 m (= 0.30 ha) b) Inner area: around 40 × 40 m (= 0.16 ha) |

| Construction | Wood earth |

| State of preservation | No longer visible on the ground, largely built over in a modern way and thus destroyed |

| place | Osterhofen |

| Geographical location | 48 ° 43 '28.3 " N , 13 ° 0' 40.7" E |

| height | 318 m above sea level NHN |

| Previous | Fort Moos-Burgstall (west) |

| Subsequently | Künzing Fort (southeast) |

The small fort Osterhofen-Haardorf was an early Roman small fort in Haardorf, a district of Osterhofen in the Deggendorf district , Lower Bavaria . The ground monument , which was largely destroyed in the 20th century, was founded on the Raetian Danube Limes in the course of the early Roman conquest in the Claudian , possibly also the Neronian times.

location

The small facility was strategically located on a small but dominant sand ridge above the Danube . The ridge known as Mühlberg is oriented slightly northwest-southeast and meets in the east towards the bank in the apex area of the Mühlhamer Loop, one of the few intact natural Danube loops in Bavaria that makes a 180-degree curve. The Mühlbach flows into the Danube along the southern slope of the Mühlberg. Shortly before its mouth, it dug itself deep into the terrain. The small fort occupies the east end on the ridge and thus the area near the Danube loop. The crew could have monitored the ship traffic and the opposite bank very well. Due to the special topographical position of the Mühlberg, a wide all-round view in all directions was possible. As the evaluation of the food waste from the garrison showed, the landscape was still very primeval at the time of the beginning Roman settlement. At that time the soldiers found extensive riparian forests with rich undergrowth in which red deer , aurochs , wild boars and beavers romped about.

Research history

In 1954 the Benedictine Father Herbert Folger (1909–1972) noted that Roman pottery finds were discovered at the southwest end of Haardorf, which at that time still belonged to the community of Aicha. Already since the early 1980s, an almost circular facility with double trenches on the Mühlberg was known from aerial surveys. At that time, the construction of private homes had already destroyed a large part of the interior space as well as the southern areas of the ground monument. Although several field inspections were subsequently carried out on the square, no datable reading finds were discovered. When the construction of the still preserved north side of this unknown structure was to begin in spring 1992, an emergency excavation of the district archeology was inevitable. In the course of this rescue excavation, the remains of a Roman fort surprisingly came to light. They were first researched by the Roman provincial archaeologist Günther Moosbauer and the prehistorian Franz Schopper . In 1995, 1996 and 1998, the Provincial Roman archaeologist Helmut Bender led the excavation campaigns as part of three teaching excavations of the Chair of Archeology of the Roman Provinces at the University of Passau . Due to the modern development, only the northern part of the complex with the approaches of the western and eastern flanks could be documented.

After the excavations, the last remainder of the fort area was released for building over.

Building history

Finds from the Neolithic to the pre-Roman Iron Age testify to the very early settlement activity on the Mühlberg. The Romans chose the place to secure the Roman imperial border, which was pushed up to the Danube, and the province of Raetia et Vindelicia, which was set up during the reign of Emperor Tiberius (14–37) or under Claudius (41–54) . Since Claudius the Danube border has been secured by forts, small forts and watchtowers and connected to one another via the Donausüdstraße . The Osterhofen-Haardorf small fort also belonged to this system. On the basis of the few small finds that existed, Bender came to the conclusion that the small fortification on the Mühlberg must have been built during the reign of Emperor Claudius.

After the mechanical removal of the topsoil and the plastering of the subgrade, three parallel trenches stood out clearly from the ground in 1992. Ultimately, a total of four trenches could be observed on the 55 × 55 meter (= 0.30 hectare) facility, which belonged to two construction phases with two double-pointed trenches each. The outer ditch on the sloping side of the river may have failed. In any case, he left no traces in this area. Due to the type of post positions that were preserved, the excavators were able to develop a surrounding wall constructed as a wood-earth construction. As early as 1992, a usable interior area of around 40 × 40 meters (= 0.16 hectares) could be calculated from the reconstructable traces of expansion of the camp. So there would have been space for two barracks with 20 to 30 soldiers.

No civil camp village ( vicus ) is known from the vicinity of the fortification . The unknown department detached to Haardorf came from one of the nearby auxiliary troop fort.

The End

Like the small forts Nersingen , Burlafingen and Weltenburg-Galget built at the same time on the Danube, the complex in Haardorf only existed for a relatively short period of time. The Austrian provincial Roman archaeologist Kurt Genser could imagine that the fortifications on the Mühlberg in particular were considered superfluous, "since nobody settled on the other bank of the Danube and the primeval forests of the Bavarian and Bohemian Forest would have made any approach of larger Germanic groups more difficult anyway."

A layer of fire that could be observed during the excavations may be due to the military power struggles in the four-emperor year 69 AD. A somewhat later end of the Haardorf garrison is also possible.

Monument protection

The facilities mentioned are protected as registered ground monuments within the meaning of the Bavarian Monument Protection Act (BayDSchG) . Investigations and targeted collection of finds are subject to authorization, accidental finds must be reported to the monument authorities.

literature

- Karl Schmotz: The archaeological preservation of monuments in the Deggendorf district during 1992 . In: Deggendorfer Geschichtsblätter 16, 1995, pp. 7-27.

- Günther Moosbauer, Franz Schopper: The early imperial small fort from Haardorfer Mühlberg, city of Osterhofen, district of Deggendorf . In: Lectures of the 12th Lower Bavarian Archaeological Day, Marie Leidorf, Rhaden 1994, pp. 207–237.

- Helmut Bender, Vera Hautmann, Janine M. van Brackel, Beáta Rudan: The early imperial small fort Osterhofen-Haardorf, district of Deggendorf (Lower Bavaria) . In: Bayerische Prehistorisches Blätter 64, 1999, pp. 133–158.

- Joris Peters, Nadja Pöllath: Food waste with a high proportion of game from the small fort in Osterhofen-Haardorf . In: Bavarian History Leaves 64, 1999, pp. 159-165.

Remarks

- ^ A b c d Karl Schmotz: The archaeological preservation of monuments in the Deggendorf district during 1992 . In: Deggendorfer Geschichtsblätter 16, 1995, pp. 7-27; here: p. 20.

- ^ A b c Karl Schmotz: The archaeological preservation of monuments in the Deggendorf district during 1998 . In: Deggendorfer Geschichtsblätter 22, 2001, pp. 21-22; here: p. 22.

- ↑ Joris Peters, Nadja Pöllath: Food waste with a high proportion of game from the small fort in Osterhofen-Haardorf . In: Bavarian History Leaves 64, 1999, pp. 159-165.

- ↑ Herbert Folger: Swikkersperch. Contributions to the history of Schweiklberg and the Vilshofen district in Lower Bavaria . Schweikelberg Abbey, 1954, p. 50.

- ↑ a b Wolfgang Czysz , Karlheinz Dietz , Hans-Jörg Kellner , Thomas Fischer : Die Römer in Bayern , Theiss, Stuttgart 1995, ISBN 3-8062-1058-6 , p. 78.

- ^ Karl Schmotz: The archaeological preservation of monuments in the Deggendorf district during 1998 . In: Deggendorfer Geschichtsblätter 22, 2001, pp. 21-22; here: p. 21.

- ↑ Helmut Bender, Vera Hautmann, Janine M. van Brackel, Beáta Rudan: The early imperial small fort Osterhofen-Haardorf, district Deggendorf (Lower Bavaria) . In: Bavarian History Leaflets 64, 1999, pp. 133–158; here: p. 141.

- ^ Sebastian Sommer : Kastellvici on the Raetian Danube Limes. Structure and function . In: Karl Schmotz (Ed.): Lectures of the 26th Lower Bavarian Archaeological Day, 2008, pp. 253–284; here: p. 276.

- ↑ Kurt Genser: Origin and development of the middle Danube Limes ( Linz archaeological research ), Nordico-Museum, Linz 2001, ISBN 3854845731 , p. 13.

- ↑ Helmut Bender, Vera Hautmann, Janine M. van Brackel, Beáta Rudan: The early imperial small fort Osterhofen-Haardorf, district Deggendorf (Lower Bavaria) . In: Bavarian History Leaflets 64, 1999, pp. 133–158; here: p. 142.