Fort Munningen

| Fort Munningen | |

|---|---|

| limes | ORL 68a ( RLK ) |

| Route (RLK) | Alblimes |

| Dating (occupancy) | around 90 AD to 110 AD at the latest |

| Type | Cohort fort |

| size | 179 × approx. 150 m (= 2.7 ha) |

| Construction | Wood earth |

| State of preservation | Largely preserved as an invisible ground monument |

| place | Munningen |

| Geographical location | 48 ° 55 '37.7 " N , 10 ° 36' 7.5" E |

| height | 516 m above sea level NHN |

| Previous | Fort Oberdorf |

| Backwards | Fort Burghöfe (southeast) |

| Upstream |

Fort Halheim (north-west) Fort Ruffenhofen (north-north-west) Fort Unterschwaningen (north) Fort Gnotzheim (north-north-east) Fort Theilenhofen (northeast) |

The Munningen fort was a short-term Roman cohort fort north of Munningen , a municipality in the Donau-Ries district , Bavaria . The fortification was founded around 90 AD in the northeastern edge zone of the Nördlinger Ries . After the garrison had withdrawn in 110 AD at the latest, a civil street vicus developed at this place , which went under with the Limes Falls around the middle of the 3rd century.

location

The Ries explosion crater, filled with fertile loess, became a preferred settlement area for arable farmers early on. Various prehistoric sites and settlements can also be found around Munningen . The flat basin of the Ries level, which divides the Swabian from the Franconian Alb , also enabled quick connections through these low mountain ranges and simplified contacts between the Alpine foothills and Central Franconia . These geographical advantages were already known to the Romans when the first Danube forts were built in the late Iberian - early Claudian times. With these facilities, the Via Claudia Augusta , a major Roman road that ran across the Alps , was built , which reached via Augsburg to the Burghöfe fort on the Danube, a troop base opposite the entrance to the Ries basin.

Fort Munningen was founded on a flat, sloping ground elevation near the northeast edge of the Ries basin. The Wörnitz , a tributary of the Danube running south , is located about 300 meters east of the garrison site. The Grimmbach flows in the lowland to the south of the fort, and the Mühlbach towards Wörnitz in the north. The fort location chosen to be safe from flooding rises only around nine meters above the water level of the river, but it dominates the vast surrounding area.

Research history

Initially only expressed as a presumption, the Bavarian major general and Limes researcher Karl Ritter von Popp (1825–1905) was the first to propose the thesis that the Munninger field name Auf dem Burggraben could indicate a former Roman fort. To answer this question, Popp undertook an experimental excavation for the Reichs-Limeskommission (RLK) in 1894 and actually came across masonry and Roman finds. But he could not prove a garrison.

The next research excavation took place in 1906 under the direction of RLK route commissioner Heinrich Eidam (1849–1934). He was the first to succeed in determining the military character of the facility and documenting the state of development, which was designed as a pure wood-earth construction. Eidam's excavation results were not made public until 1929 in the Limeswerk . Possibly inspired by Eidam's recently published documentation, Ernst Frickhinger (1876–1940) set the spade in Munningen in 1930. He was able to refute Eidam's assumptions about a stone extension of the fort that had begun but not been completed and proved that the stone buildings belonged to a later settlement phase of the Limes period.

Since Frickhinger never published his results in detail, the archaeologist Dietwulf Baatz was reliant on his estate for his research, which contained precise plans and records. In 1971, Baatz was the first to start an emergency excavation on the castle moat after 1930 . At that time, state road 2221 between Munningen and Oettingen was to be expanded as part of the land consolidation . This road followed the Via decumana and Via praetoria from north to south . In the meantime, the archaeologist Rolf Nierhaus (1911–1996) was able to re-date the layer of fire discovered during the old excavations. He proved that this was in no way related to the end of the Munninger Fort, but pointed to the time "around 170 AD". The excavations of 1971 brought the most informative results to date on the fort site. However, the investigations were limited to the area of the planned route widening. Therefore, only very narrow were Plana that ran from north to south, documented in various sections of the excavator deduction. Due to the limited financial resources, apart from these sightings, only a few other specifically selected areas could be recorded more precisely.

In the decades that followed, the fort site was regularly flown to by aerial photo archaeologist Otto Braasch and especially by Klaus Leidorf for over thirty years. Local researcher Werner Paa provided additional information during his field inspections, as the farmers constantly destroyed Roman structures while plowing and tore found material to the surface.

During the summer and autumn of 2008, the fort was topographically measured in several campaigns under the direction of geophysicist Jörg Faßbinder from the Bavarian State Office for Monument Preservation . The areas prospected with the magnetometer were put together in a magnetogram. For the first time, a largely complete plan of the fort and larger parts of the post-fort period Roman settlement could be documented.

In anticipation of the expansion of the 3.30-kilometer bypass around Munningen, which was opened in December 2009, excavations were again carried out very quickly on behalf of the State Monuments Office and under the direction of the archaeologist Friedrich Loré. The bypass road also served as the relocation of State Road 2221 from the town center. Due to the specifications of the monument office, the topsoil was only to be deducted to a construction depth of a maximum of 30 centimeters, all findings below were not allowed to be examined and then disappeared unseen under the new building terrace. Since colluvial layers and flat topsoil remnants often disrupted a clean subgrade due to the low level of removal, some Roman findings have probably remained undetected. Particularly in the northern area of the bypass, in the area of the post-fortified vicus, further building remains and 18 Roman wells were uncovered, of which only three were fully examined.

Building history

Due to its fertility, the early Roman occupation policy north of the Danube aimed, among other things, at securing the Ries basin. With the construction of a wedge shaped sheet of military posts between the Kastell Steingädele about Kastell Pfünz to in the spring 80 n. Chr. Founded Kastell Kosching the Rieser should settlement chamber of the province Rätien be added. According to ceramic dating , Fort Pförring was only added during the reign of Emperor Trajan (98–117). Around the same time as Munningen, further fort complexes such as the Domitian cohort fort Gnotzheim and Weißenburg and the number fort Unterschwaningen, which was presumably subordinate to Gnotzheim, were built in the run-up to the Ries basin . The Oberdorf fort west of the Ries is also attributed to this period. The Burghöfe fort with the Via Claudia Augusta stood in the middle of the southern axis of this wedge, which was pushed across the Danube and at the tip of which was Unterschwaningen. The chain of garrisons now secured the civil settlement of the Ries.

It is assumed that the Ruffenhofen fort was only added in a second expansion phase in order to close a gap in this wedge-shaped arch. At that time Munningen, which was now in the Limes hinterland, was given up as a garrison location.

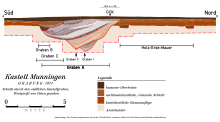

Enclosure

The fort area encompassing 179 × approx. 150 meters (= 2.7 hectares) from the outer sides of the fence was built as a typical wood-earth system with rounded corners (playing card outline) during the first military occupation of this area. Together with other fortified camps, it formed the Alblimes and was associated with the first chain of castles that was pushed across the Danube, but which quickly lost its importance in the Rhaetian region due to new military sites that were pushed further north. The excavations of 1971 could fix the founding years to the time around 90 AD, when Emperor Domitian (81-96) ruled. The soldiers first dug a surrounding trench to build the fort. This pointed ditch (ditch I), which was already around 0.20 to 0.35 centimeters below the top of the terrain, was too steep in Munningen and had to be re-excavated with a less steep slope after several falls (ditch II). With the excavation, a 5.60 meter wide wall was built behind the trench, which was constructed using the wood-earth technique. As shown by the post ditches and post stand traces found on the eastern flank as well as on the north and south fronts in 1906 and 1971, the earth was similar to the Künzing II fort in a box construction that consisted of two parallel, vertical front and rear sides. The magnetometer inspection in 2008 confirmed, among other things, the comparatively wide berm that has already been proven . Since the modern state road runs directly above the rear gate, the Porta decumana , and the main gate, the Porta principalis , these gates have remained unexplored to this day. In the assessment conducted by Faßbinder in 2008, it was also possible to establish that the weir ditch had no interruption in front of the four entrances to the gates. In addition, no corner or intermediate towers could be detected.

Warehouse interior

The structures of the interior buildings used during the military stationing period are largely unexplored archaeologically. However, the excavations in 1971 provided the first glimpses of the structure of the regularly arranged soldiers' barracks. The contubernia of these barracks have a size of 27.40 square meters. According to Baatz, the orientation of the camp is unclear, since the structure of the central staff building ( Principia ) , which could provide information about it, is located under the modern street and is therefore not archaeologically comprehensible. In addition, it has not yet been possible to clarify the location of the two principal gates on the side. They would also help to clarify this question. Neither Eidam with his excavation on the eastern perimeter wall had a clear success, nor did Faßbinder with the magnetometer. The geophysicist speculated that various factors are responsible for this fact. On the one hand, this could be due to the low construction depth of the wooden structures; on the other hand, the soil erosion favored by agriculture will in many cases have removed the last traces. The later metamorphosis from fort square to street vicus may have destroyed many structural details. Faßbinder also pointed out that the variable magnetic field disturbances emanating from modern road traffic make many possible but weak findings no longer recognizable.

Baatz recognized in his plan in the north-western camp area behind the singular ditch and the traces of the fortifications, four barracks arranged in pairs facing the main camp road, between which narrow sewer ditches ran. On the opposite, eastern side of the main camp road, which runs through the fort from the north to the Principia in the middle of the camp , a small section gave a very similar picture of the development. To the south of the four barracks, Baatz could observe a camp road running west-east that delimited the median of the fortification (Latera praeetorii) . In the central reservation itself, Baatz could not find any buildings dating from the fortress period in the area of its narrow section, but a little further south he encountered another west-east oriented camp road, which obviously formed the southern boundary of the Latera praeetorii . Subsequently, further barracks oriented from west to east followed in the north-south running dredger section, whose use can only be speculated on due to the very limited investigation area. In this area, too, the buildings were separated from each other by sewage channels. The southern end of the fort was again marked by the rampart bordered by palisades and the singular defensive moat.

End of the plant

The end of the complex can be dated through the clear stratification of certain finds from the fort moat. The salvaged late South Gallic relief sigillata from Banassac gives a term ante quem . This was found in the youngest backfill layer of the trench and had obviously already got into the ground by residents of the post-fortified street village. This last backfill, as its peaty contents showed, remained open as a swampy strip for a long time after the withdrawal of the military (trench C). The rubbish disposed of there by the vicus population comprised a remarkable number of ceramic shards, some of local design, which could often still be assembled into complete vessels. According to Baatz, the Sigillata from Banassac can be prescribed between 100 and 110 AD. At this point the fort was already deserted. As the shift observations inside the camp showed, the soldiers had peacefully cleared the inner buildings, then laid them down and finally leveled the area. The troops may have been moved to the new, more northerly border line. Baatz assumed that the crew set up the wood-earth warehouse in Theilenhofen .

Fort bath

In 1977 the small stone military bath was discovered not far from the fort, on its southern arterial road, between the cycle path and the state road at the exit of Munningen, and after the investigation was completed it was covered with humus. An originally planned visualization and conservation did not take place. The bathroom is a type of facility known as a row bathroom, which means that the visitor stepped through the rooms to the individual bathing and sweating rooms according to a set program. According to the regulations, the building is oriented in its longitudinal axis to the north. The bathroom was entered from the north via an undressing and dressing area, the apodyterium . At the southern end there was the heating system ( praefurnium ) with the hot water boilers (vasa) .

Militaria finds

Two fragments of military diplomas are among the most important militaria from Munningen . Unfortunately, only the text area that refers to the public display of the diplomas in Rome has survived in both documents, but the text that has been preserved indicates that the originals of the bronze tablets were displayed at the temple of the deified Augustus in Rome. The certified copy was sent to the recipient of a diploma. This important document guaranteed Roman citizenship to a soldier of the auxiliary troops who was honorably discharged from the army. The officially pre-formulated text of the inscriptions proves through the location of the hanging that the bronze documents were created around AD 98/90, when the Augustus temple was rebuilt after a fire disaster.

Civil settlement

Buildings on the fort area

After the fall of the fort, a Roman street village was built on this site along the routes to Gnotzheim and Ruffenhofen. This place could have been known as Losodica . On the Tabula Peutingeriana , the medieval copy of a late Roman road map, this name lies between the not clearly identified Septemiaci and Medianis (Gnotzheim Castle). According to Septemiaci there are seven (≈ 10.37 kilometers), to Medianis eleven Roman miles (≈ 16.30 kilometers). Stone buildings in the area of the former fort are also documented for this village, as are the ared cremation graves on the east side of the vicus. Traces of metal processing point to economic activities of the residents, as does a crockery depot from Rheinzabern Terra Sigillata, which was obviously affected during the Marcomann Wars (166–180). Further traces of fire and destruction in the period around 170 AD were also found in the investigations in 1971. The further history of the village is difficult to grasp, as agriculture has destroyed the younger strata. Considerations as to whether there was a higher administrative unit or a street station ( Mansio ) in Munningen are speculative. Two larger stone foundations on the fort area, which Eidam cut in 1906, could indicate that storage buildings existed in Munningen to store food for the border troops. A military reuse of parts of the fort area would thus be given. After the destruction of the Marcomann Wars, it was rebuilt, as a rectangular hall building with strong foundations was built from spoils , which had a portico designed as a vestibule . The last coin found possibly related to the vicus was minted during the reign of Emperor Philip Arabs (244–249). At the latest with the Limes fall in AD 159/260, the place was finally destroyed.

Horror

In 2009, investigations were carried out on the Munningen bypass, which is under construction. After the topsoil had been removed, the excavators discovered a wooden hall structure that was at least 38 meters long and 18 meters wide, possibly with three aisles, to the southwest of the fort. The square post pits that appeared in the planum during his investigation were around 1.20 × 1.20 meters in size and contained very well-preserved, up to 0.70 meters thick pine stands that were still up to 0.80 meters high. Eleven could be dendrochronologically evaluated after their recovery . It turned out that they had been felled in late spring or early summer 112 AD (edge of the forest), i.e. shortly after the fort was abandoned and rededicated. This construction could also have served as a horreum for storing food, most likely grain.

Two better-documented three-aisled wooden halls, each around 46 × 24 meters in size, were found in 1981 northeast of the rear Danube fort Oberstimm . There the youngest coin from a rubbish pit also dates from the reign of Emperor Trajan. The garrison in Oberstimm was also abandoned in the Trajan-Early Hadrian period.

Handling stamp

A Gallo-Roman temple was uncovered close to the fort and the foundations of a multi-phase stone building were revealed around 20 meters south of it. Among other things, the remains of a Lorica Segmentata , two heads of small stone statuettes, the heavily destroyed remains of two inscription tablets and large amounts of burned animal bones were found there. The building may have had a public function. Further dendrodata from the vicus are from the years 104 ± 10, late spring 113 (well box), 117 (wooden barrel, secondarily installed in a well) and 119 AD (wooden barrel, secondarily installed in a well). In addition, the wells provided data from AD 107 and from around AD 144 ± 8.

Early medieval settlement

Only in the 6th to 7th centuries are traces of settlement again documented at this place. In the northern part of the former vicus, parts of an Alemannic row grave field were uncovered during the investigation of the fort by Eidam. 40 graves could be identified, of which 30 graves were systematically excavated in autumn 1906. In September 1909, the Dillingen Historical Society examined six more graves. Numismatist Julius Cahn (1871–1935) described a gold coin find discovered in 1906 in 1930. In grave 1, nine gold coins were found in the remains of a pocket. In addition to a coin from the reign of the Eastern Roman emperor Tiberius Constantinus (578-582), the remaining pieces were barbaric replicas of Eastern Roman solidi and tremisses. Parts of the burial ground were also cut in 1971.

Monument protection

The fund areas and the other facilities mentioned are protected as registered ground monuments within the meaning of the Bavarian Monument Protection Act (BayDSchG). Investigations and targeted collection of finds are subject to authorization, accidental finds must be reported to the monument authorities.

Web links

- Fort and Vicus Munningen . arachne.uni-koeln.de, University of Cologne, Archaeological Institute.

literature

- Heinrich Eidam : The Munningen fort . (= The Upper German-Raetian Limes of the Roman Empire, Department B, Volume 6, Fort No. 68a). Petters, Heidelberg / Berlin and Leipzig 1929.

- Friedrich Fischer: The excavations of the association for local history in the Ries . In: Yearbook of the Historical Association Dillingen an der Donau 22 (1909), pp. 120–128; here: p. 126 (the Roman finds from 1909)

- Hans Ulrich Nuber : Comments on military diplomas and a newly found fragment from Munningen, Nördlingen district . In: Germania 47, 1969, pp. 178-188.

- Dietwulf Baatz : The Munningen fort in the Donau-Ries district . In: Annual report of the Bavarian soil monument maintenance, 15/16 (1974/75), Munich 1977, pp. 108–120.

- Dietwulf Baatz: The Munningen fort in the Nördlinger Ries . In: Saalburg-Jahrbuch 33 (1976), pp. 11-62.

- Hermann Ament : New Alemannic grave finds from Munningen, Donau-Ries district . In: Saalburg-Jahrbuch 33 (1976), pp. 63-74.

- Wolfgang Czysz : Settlement structures of the Roman Empire in the Ries . In: Rieser Kulturtage , Documentation, Volume 7 (1988); Nördlingen 1989, pp. 97-115.

- Werner Paa: Losodica. The Roman fort and the civil settlement of Munningen . Steinmeier, Nördlingen 1998, ISBN 3-927496-48-0 .

- Jörg Faßbinder, Thomas Deller, Lena Kühne, Tomasz Gorka: Magnetometer prospection of Fort Losodica / Munningen, Donau-Ries district, Swabia . In: The archaeological year in Bavaria 2008, pp. 70–73.

- Thomas Fischer , Erika Riedmeier-Fischer: The Roman Limes in Bavaria , Pustet, Regensburg 2008, ISBN 3-7917-2120-8 , p. 185 f.

- Friedrich Loré: Barrels and Fountains. Timber conservation in the Roman vicus of Munningen . In: The archaeological year in Bavaria 2009 (2010), pp. 95–98.

- Franz Herzig, Stefanie Berg-Hobohm : Roman barrel and box wells in the vicus of Munningen - excavations in the area of the new bypass . In: Denkmalpflege Informations , 145 (2010), pp. 11–13.

Remarks

- ↑ Kastell Burghöfe at 48 ° 38 '49.78 " N , 10 ° 49' 32.03" O

- ^ Dietwulf Baatz : The Munningen fort in the Donau-Ries district . In: Annual report of the Bavarian monument preservation , 15/16 (1974/75), Munich 1977, pp. 108-120; here: p. 109.

- ↑ a b Jörg Faßbinder , Thomas Deller, Lena Kühne, Tomasz Gorka: Magnetometer prospection of Fort Losodica / Munningen, district of Donau-Ries, Swabia . In: The archaeological year in Bavaria 2008, pp. 70–73; here: p. 70.

- ^ Dietwulf Baatz : The Munningen fort in the Donau-Ries district . In: Annual report of the Bavarian monument preservation , 15/16 (1974/75), Munich 1977, pp. 108-120; here: pp. 109–110.

- ^ A b Dietwulf Baatz : The Munningen fort in the Donau-Ries district . In: Annual report of the Bavarian monument preservation , 15/16 (1974/75), Munich 1977, pp. 108-120; here: p. 111.

- ↑ Ernst Frickhinger in: Bavarian history sheets 10 (1931/32), p. 107 f.

- ↑ a b c d Dietwulf Baatz : The Munningen fort in the Donau-Ries district . In: Annual report of the Bavarian monument preservation , 15/16 (1974/75), Munich 1977, pp. 108-120; here: p. 113.

- ↑ a b c Jörg Faßbinder, Thomas Deller, Lena Kühne, Tomasz Gorka: Magnetometer prospection of Fort Losodica / Munningen, Donau-Ries district, Swabia . In: The archaeological year in Bavaria 2008, pp. 70–73; here: p. 72.

- ^ Friedrich Loré: Barrels and fountains. Timber conservation in the Roman vicus of Munningen . In: The archaeological year in Bavaria 2009 (2010), pp. 95–98; here: pp. 96–97, here: pp. 95–97.

- Jump up ↑ Castle Urspring at 48 ° 33 ′ 0 ″ N , 9 ° 54 ′ 2.5 ″ E

- ↑ Fort Pfünz at 48 ° 53 ′ 2 ″ N , 11 ° 15 ′ 50 ″ E

- ↑ AE 1907, 00186 ; AE 1907, 00187 ; Inscription at Ubi erat lupa .

- ↑ Kösching Fort at 48 ° 48 ′ 39 ″ N , 11 ° 29 ′ 59 ″ E

- ↑ Fort Pförring at 48 ° 49 ′ 6.5 ″ N , 11 ° 40 ′ 56.5 ″ E

- ^ Rüdiger Krause : Ries . In: Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde , de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2003, ISBN 3-11-017575-4 , pp. 589–601; here: p. 590; Günter Ulbert, Thomas Fischer: The Limes in Bavaria . Theiss, Stuttgart 1983, ISBN 3-8062-0351-2 , p. 112.

- ↑ Gnotzheim Fort at 49 ° 3 ′ 25.9 ″ N , 10 ° 42 ′ 16.2 ″ E

- ↑ Weissenburg Fort at 49 ° 1 ′ 51 ″ N , 10 ° 57 ′ 45 ″ E

- ↑ Castle Unterschwaningen at 49 ° 4 ′ 10.25 ″ N , 10 ° 37 ′ 20.54 ″ E

- ↑ Fort Oberdorf at 48 ° 52 ′ 7 ″ N , 10 ° 20 ′ 30 ″ E

- ↑ Ruffenhofen Fort at 49 ° 2 ′ 47.21 ″ N , 10 ° 28 ′ 49.97 ″ E

- ↑ a b Jörg Faßbinder, Thomas Deller, Lena Kühne, Tomasz Gorka: Magnetometer prospection of Fort Losodica / Munningen, district of Donau-Ries, Swabia . In: The archaeological year in Bavaria 2008, pp. 70–73; here: p. 71.

- ↑ Werner Zanier , Angela von den Driesch , Corinna Liesau, Peter Schröter: The Roman fort Ellingen (= Limes research 23), Zabern, Mainz 1992, ISBN 3-8053-1264-4 , p. 62.

- ^ A b Dietwulf Baatz : The Munningen fort in the Donau-Ries district . In: Annual report of the Bavarian monument preservation , 15/16 (1974/75), Munich 1977, pp. 108-120; here: p. 114.

- ↑ Fort bath Munningen at 48 ° 55 '30.9 " N , 10 ° 36' 8.61" E

- ↑ AE 1969/70, 00449a ; Werner Eck : Public, Politics and Administration. Epigraphic documents from emperors, senates and officials in Rome . In: Rudolf Haensch (Ed.): Vestigia. Self-expression and communication. Publication of state documents on stone and bronze in the Roman world . (= Contributions to Ancient History 61), C. H. Beck, Munich 2009, ISBN 978 3 406 58287 5 , pp. 75–96, here: pp. 83–85.

- ^ Dietwulf Baatz : The Munningen fort in the Donau-Ries district . In: Annual report of the Bavarian monument preservation , 15/16 (1974/75), Munich 1977, pp. 108-120; here: p. 118.

- ^ Dietwulf Baatz : The Munningen fort in the Donau-Ries district . In: Annual report of the Bavarian monument preservation , 15/16 (1974/75), Munich 1977, pp. 108-120; here: p. 119.

- ^ Dietwulf Baatz : The Munningen fort in the Donau-Ries district . In: Annual report of the Bavarian monument preservation , 15/16 (1974/75), Munich 1977, pp. 108-120; here: pp. 119–120.

- ^ Friedrich Loré: Barrels and fountains. Timber conservation in the Roman vicus of Munningen . In: The archaeological year in Bavaria 2009 (2010), pp. 95–98; here: p. 95.

- ↑ Fort Oberstimm at 48 ° 42 ′ 43.9 ″ N , 11 ° 27 ′ 18.49 ″ E

- ^ Karl-Heinz Rieder: Roman hall buildings near Oberstimm, Manching community, Pfaffenhofen ad Ilm district, Upper Bavaria . In: The Archaeological Year in Bavaria 1982 (1983), pp. 101-103; here: p. 103.

- ↑ Hans Schönberger u. a .: Oberstimm Castle. The excavations from 1968 to 1971. (= Limes research - studies on the organization of the Roman border on the Rhine and Danube 18), Mann, Berlin 1978. p. 28; Hans Schönberger u. a .: Oberstimm Castle. The excavations from 1968 to 1971. (= Limes research - studies on the organization of the Roman imperial border on the Rhine and Danube 18), Mann, Berlin 1978. p. 147.

- ^ Friedrich Loré: Barrels and fountains. Timber conservation in the Roman vicus of Munningen . In: The archaeological year in Bavaria 2009 (2010), pp. 95–98; here: p. 98.

- ↑ C. Sebastian Sommer : Trajan, Hadrian, Antoninus Pius, Marc Aurel ...? - To date the systems of the Raetian Limes . In: Report of Bayerische Bodendenkmalpflege 56 (2015), pp. 321–327; here: p. 142.

- ^ Friedrich Loré: Barrels and fountains. Timber conservation in the Roman vicus of Munningen . In: The archaeological year in Bavaria 2009 (2010), pp. 95–98; here: pp. 96–97.

- ↑ University of Bern, Institute for Archaeological Sciences, preview of the dissertation work by Andreas Schaflizl: Siedlungsgeschichte des Vicus Munningen, Bavaria, D, based on new excavation results ( Memento of the original from October 21, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. ; accessed on October 21, 2016

- ↑ a b Julius Cahn: A gold coin find from the early 7th century from the grave field of Munningen . In: Germania 14, (1930), pp. 161–165 (also in Frankfurter Münzzeitung 2, 1931, pp. 325–328).

- ↑ Friedrich Fischer: The excavations of the association for local history in the Ries . In: Yearbook of the Historical Association Dillingen an der Donau 22 (1909), pp. 120–128; here: p. 124.

- ↑ Heiko Steuer : Bag . In: Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde 35, de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2007, ISBN 978-3-11-018784-7 , pp. 72–82; here: p. 77.