Wood-earth fort on the Spread in Weißenburg

| Wood-earth fort on the Spread in Weißenburg | |

|---|---|

| Alternative name | Weissenburg wooden fort |

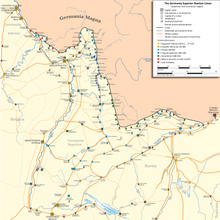

| limes | ORL NN ( RLK ) |

| Route (RLK) | Rhaetian Limes, route 14 |

| Dating (occupancy) | Trajan / early Hadrian or shortly after 150 AD |

| Type | Cohort fort |

| unit | Cohors IX Batavorum equitata milliaria exploratorum (?) |

| size | 240 × 160 m (= 3.2 ha) |

| Construction | Wood earth |

| State of preservation | Ground monument; largely destroyed by modern development |

| place | Weißenburg in Bavaria |

| Geographical location | 49 ° 2 '7.5 " N , 10 ° 59' 12.7" E |

| height | 435 m above sea level NHN |

| Previous | Weissenburg Castle (southwest) |

| Subsequently |

Fort Oberhochstatt (east) Burgus Burgsalach (east) |

| Backwards |

Fort Munningen (west-southwest) Fort Faimingen (south-west) Fort Pfünz (south-east) |

| Upstream |

Fort Ellingen (north) Small fort Gündersbach (north) |

The wood-earth fort on the Breit in Weißenburg , which is also known as the Weissenburg wood fort , was a Roman military camp that was built near the Upper Germanic-Rhaetian Limes , a UNESCO World Heritage Site , and in the urban area of Weißenburg in the Middle Franconian district of Weißenburg- Gunzenhausen is located. The facility is located around 1.60 kilometers north-east of the Weißenburg Reiterkastell on the Breiter Flur.

Location and research history

The facility, which was only occupied for a short time, was built on a large, flat plateau above the exit of the Rohrbach Valley and oriented with its long side in a north-west-south-east direction. At the same place there was previously a middle to late Latène period homestead settlement and a Viereckschanze nearby.

The dry summer of 1976 made it possible for the aerial photo archaeologist Otto Braasch to perceive the double trenches of a large Roman wood-earth warehouse in the then undeveloped corridor "Breit". At the same time, the Celtic Viereckschanze was found, of which nothing had been preserved above ground.

In September 1976 the excavator was able to make seven search cuts through the moat of the fort. In the summer of 1978 it became known that an area of over 9,000 square meters in the southwestern fort area was to be destroyed by the construction of a new district hospital (today Altmühlfranken Clinic ), which began in 1981 . The excavations that are now beginning took place with interruptions from February 28 to June 1, 1979 and were under the local direction of excavation technician Ferdinand Leja from the Nuremberg branch of the Bavarian State Office for Monument Preservation. The archaeologist Harald Koschik was in charge of the scientific management. After the extensive removal of the topsoil and the installation of three test areas, there were no traces of internal development on the subgrade for Leja and Koschik. In addition, not a single find was recovered there. A further examination of the interior of the fort could therefore be dispensed with. Now excavator cuts were made again through the double trench, both on the southwest corner and immediately east of the south gate.

In two further excavation campaigns, which took place in 1984 and 1985, the archaeologist Claus-Michael Hüssen succeeded in examining the eastern part of the fort, around a quarter of the entire complex. With the excavations from 1986 and 1989 to 1991, which were also led by Hüssen in cooperation with the Roman-Germanic Commission , the camp was then almost completely investigated. In contrast to Leja and Koschik, Hüssen was able to provide evidence of a wooden interior structure, even right next to the area that was built in 1979.

These excavations had become necessary because the ground monument stood in the way of a planned new building area and a bypass road. The evaluation of the findings and the small amount of Roman as well as the rich Latène period finds was carried out at the Ingolstadt branch of the Roman-Germanic Commission, headed by Hüssen since 1990. In Weißenburg it was possible for the archaeologists in Germany for the first time to fully examine such a large single-phase wood-earth fort with its internal structure made of post structures.

Building history

Enclosure

In addition to the wood-earth warehouse built around the year 90 , which was later expanded in stone, there is a second fort site in Weißenburg, which is a rectangular, somewhat displaced, 240 × 160 meters (= almost 3.2 hectares) large wood-earth plant was built. The rounded four corners (playing card shape) were typical of the basic shape of mid-imperial forts.

The garrison location was enclosed by two pointed trenches that were 2.80 to 4.60 meters wide and a maximum of 2.40 meters deep. These trenches had a slope angle between 35 and 45 degrees and were sunk into a very hard calcareous rubble soil, which was in places interspersed with sand and clay lenses. The hardness of the soil made the trench walls extremely stable. The relatively small depth of the trenches can, among other things, be explained by a high groundwater level. The reason for this is a clay bench beneath the layer of limestone rubble that accumulates the water.

A double-lane gate passage had been built on all four sides, which were divided by the Spina . This spina also supported the gate bridge, which connected the towers flanking the gate. In front of these gates the two enclosing trenches were suspended , but direct access to the gate was prevented by short trenches ( titula ) in front . Hüssen assumed that the fort's rising fortification consisted of a four to five meter wide turf wall with a parapet. However, no trace of any of this was left. Only sparse remains of the wooden defensive structures have survived. In the area of the west gate, the post pits of the spine , which were sunk into the natural ground, could still be seen, and traces of the wooden gate towers and the spine were also visible on the east gate . In the northeast corner, deep post pits of an approximately 5 × 5 meter corner tower could be examined.

Interior development

The somewhat oblique-angled plan of the defense also determined the appearance of the interior buildings. Like the trenches, the camp barracks, administration buildings and possible warehouse buildings were also single-phase. Only individual posts of the clearly recognizable wooden structures have been replaced during the period of use. The short-term nature of the camp can also be determined from the fact that the archaeologists could not find any supply facilities such as wells, cisterns, sewers or the like. Even garbage pits were nowhere to be found. There were no traces of the central buildings such as the Principia (staff building) in the deeply plowed humus. It is possible that these buildings were constructed in a different way than the surrounding barracks. A foundation on threshold beam or post trenches would be conceivable.

Troop

The complete plan of the camp allows statements about the strength and composition of the stationed troops. In terms of the number and internal structure of the buildings, a Cohors milliaria equitata can be thought of. In 1985, Huss suggested that the Cohors IX Batavorum equitata milliaria exploratorum , as evidenced by inscriptions for Weißenburg, might have taken garrison here. The inscription comes from a votive altar for Jupiter that was walled up on the Weissenburg Andreaskirche until 1892 .

End as well as finds from before and after the period

With the planned withdrawal of the troops and the evacuation of the camp, the wooden structures inside the defense were at least partially laid down. However, the moats must have remained open and have slowly filled in naturally. In the resulting lower flood layers, some finds from the second half of the 2nd century were found. Along with these findings, bones came to light. As early as 1979, Koschik had uncovered bone fragments from five men and a child, skeletal remains of two horses and a dog at the south gate. Hüssen was also able to establish a similar finding up to 1985. Human and animal bones were scattered around the post-fortified finds. The archaeologist initially speculated that this material could be seen in connection with armed events during the Marcomannic Wars (166-180). It is now clear that at least the human bones come from the Middle to Late Latene Period homestead settlement that previously stood on this site.

Time position

Despite the rather sparse finds, Hüssen decided to use the camp for a short time during the Trajan - Early Hadrian period after it was processed , whereby the end of the camp "at the latest in the late Trajan -Early Hadrian period", i.e. around 110 to 120 AD, was done. The small amount of finds is probably due to the scheduled evacuation of the fort. For a more precise dating, the fragments of two terra sigillata vessels of the shapes Dragendorff 18 and 27 , which were most likely found in southern Gaul , could be used. The existence of these vessel fragments led Hüssen to assume in 1985 that the place was cleared in Hadrianic times at the latest. A few fragments of pottery that were lost when the trenches were dug also pointed in this direction. In the last presentation of the fort square, Hüssen locates the fort's occupation time in the period shortly after the middle of the 2nd century.

Monument protection

The registered ground monuments with the number D-5-6931-0385, which also includes the wood-earth fort on the Breit in Weißenburg, as well as all other facilities mentioned are protected in accordance with the Bavarian Monument Protection Act (BayDSchG) . Investigations and targeted collection of finds are subject to authorization, accidental finds must be reported to the monument authorities.

literature

- Claus-Michael Hüssen : Weißenburg - On the spread . In: Suzana Matesic, C. Sebastian Sommer : At the edge of the Roman Empire (= contributions to the Limes World Heritage Site. Special Volume 3), Mainz 2015, ISBN 978-3-945751-19-0 , pp. 122–123.

- Claus-Michael Hüssen: Wood and earth fort on the spread . In: Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde 33, Berlin, New York 2006, p. 422.

- Claus-Michael Hüssen: Fort spreading in Weissenburg . In: Rainer Braun, Thomas Fischer , Jochen Garbsch (eds.): The Roman Limes in Bavaria. 100 years of Limes research . (= Exhibition catalogs of the Prehistoric State Collection 22), Prehistoric State Collection, Munich 1992, ISBN 3927806137

- Claus-Michael Hüssen: The wooden fort on the "Breit" in Weißenburg in Bavaria . In: Valerie A. Maxfield, Michael J. Dobson (Eds.): Roman Frontier Studies 1989, Proceedings of the XVth International Congress of Roman Frontier Studies . Exeter 1991, ISBN 0859897109 , pp. 191-195.

- Claus-Michael Hüssen: The Roman wood and earth fort on the "Breit" in Weißenburg in Bavaria . In: Villa nostra 2, Weißenburg 1990, pp. 10-13.

- Claus-Michael Hüssen: New results of the excavations in the wooden fort of Weißenburg in Bavaria. Weissenburg-Gunzenhausen district, Middle Franconia . In: The archaeological year in Bavaria 1985 (1986), pp. 108-109.

- Harald Koschik: The Roman field camp of Weißenburg in Bavaria . In: Annual Report of the Bavarian Heritage Monument Care 21, 1980, pp. 138–154.

- Eveline Grönke: The Roman Alenkastell Biricianae in Weißenburg in Bavaria. The excavations from 1890 to 1990 . (= Limes research 25: Studies on the organization of the Roman imperial border on the Rhine and Danube ) Zabern, Mainz 1997, ISBN 3805323182

Remarks

- ↑ Hans-Jörg Kellner , Gisela Zahlhaas , Hans-Gert Bachmann: The Roman temple treasure of Weißenburg in Bavaria . Zabern, Mainz 1993, ISBN 3805315139 , p. 12.

- ↑ Claus-Michael Hüssen: Wood-earth fort on the spread . In: Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde 33, Berlin, New York 2006, p. 422.

- ↑ a b c Harald Koschik: The Roman field camp of Weissenburg in Bavaria . In: Annual Report of the Bavarian Heritage Monument Care 21, 1980, pp. 138–154; here: p. 138.

- ^ Konrad Spindler (arrangement): District of Weißenburg-Gunzenhausen. Monuments and sites (= guide to archaeological monuments in Germany 15), Theiss, Stuttgart 1987, ISBN 3-8062-0504-3 , p. 205.

- ↑ Harald Koschik: The Roman field camp of Weißenburg in Bavaria . In: Annual Report of the Bavarian Heritage Monument Care 21, 1980, pp. 138–154; here: pp. 140–142.

- ^ Eveline Grönke: The Roman Alenkastell Biricianae in Weissenburg in Bavaria. The excavations from 1890 to 1990 . (= Limes research 25: Studies on the organization of the Roman imperial border on the Rhine and Danube ) Zabern, Mainz 1997, ISBN 3805323182 , p. 15.

- ↑ Claus-Michael Hüssen: Weißenburg (LK Weißenburg-Gunzenhausen) . In: Yearbook of the Historical Association for Middle Franconia 97, 1994, p. 453.

- ^ A b c Claus-Michael Hüssen: Lecture at the 1990 annual meeting of the Roman-Germanic Commission. Roman occupation and settlement of the Middle Rhaetian Limes area . In: Report of the Roman-Germanic Commission 71, 1990 (1991), p. 5ff .; here: p. 10.

- ↑ Weissenburg Fort at 49 ° 1 ′ 51 ″ N , 10 ° 57 ′ 45 ″ E

- ↑ Harald Koschik: The Roman field camp of Weißenburg in Bavaria . In: Annual Report of the Bavarian Heritage Monument Care 21, 1980, pp. 138–154; here: pp. 142–143.

- ↑ a b c d Claus-Michael Hüssen: New results of the excavations in the wooden fort of Weißenburg in Bavaria. Weissenburg-Gunzenhausen district, Middle Franconia . In: The archaeological year in Bavaria 1985 (1986), pp. 108-109 .; here: p. 108.

- ^ A b c Hans-Jörg Kellner , Gisela Zahlhaas , Hans-Gert Bachmann: The Roman temple treasure of Weissenburg in Bavaria . Zabern, Mainz 1993, ISBN 3805315139 , p. 19.

- ↑ CIL 03, 11918

- ^ Claus-Michael Hüssen: New results of the excavations in the wooden fort of Weißenburg in Bavaria. Weissenburg-Gunzenhausen district, Middle Franconia . In: The archaeological year in Bavaria 1985 (1986), pp. 108-109.

- ↑ Claus-Michael Hüssen: Wood-earth fort on the spread . In: Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde 33, Berlin, New York 2006, p. 422.

- ↑ Claus-Michael Hüssen: Weißenburg - On the spread . In: Suzana Matesic, C. Sebastian Sommer (Ed.): At the edge of the Roman Empire. Contributions to the Limes World Heritage . Special volume 3, Mainz 2015, pp. 122–123.