Julia Mamaea

Julia Avita Mamaea (also inscribed Mamea , Greek Ἰουλία Μαμαία; † March 235 near Mogontiacum ) was the mother of the Roman emperor Severus Alexander , who ruled from 222 to 235. At first she was because of the young age of her son actually regent , but after he had reached adulthood, they remained the dominant figure at the court. Her position of power was precarious, however, as she could neither gain authority with the Praetorians nor in the army. Finally, Alexander and Mamaea were murdered on a Germanic campaign in a soldiers' revolt. So that went dynasty of the Severi under. The era of the soldier emperors followed .

Life

Origin, youth and life as a wife

Mamaea's maternal ancestors came from the Syrian city of Emesa (now Homs ). The very rich family of her mother Julia Maesa enjoyed a high reputation there. In this family the office of high priest of the sun god Elagabal was hereditary. The Elagabal cult played a central role in the religious life of the Emesen people. Mamaea's family may have descended from the Arab dynasty that ruled the city in the 1st century before Emesa was incorporated into the Roman province of Syria . In any case, a woman named Julia Mamaea is attested in the 1st century, who was probably a sister of the last Prince of Emesa known by name, Sohaemus. She married the King Polemon II of Pontus .

Maesa was married to the knight Gaius Julius Avitus Alexianus, who was also a Syrian. Mamaea spent her childhood well with her parents and her older sister Julia Soaemias in their Syrian homeland.

The decisive course for Mamaea's life was the marriage of her aunt Julia Domna , Julia Maesa's sister, to the African Septimius Severus . When this marriage was concluded in 187, Severus' rise to the highest dignity in the state was not yet in sight. In the " second year of the four emperors" in 193 he was made emperor. In the civil wars that followed, Severus was able to prevail against his rivals. When he came to power, his sister-in-law's clan also came to the center of power. Soon after he came to power, Severus made sure that Mamaea's father Avitus, his sister-in-law's husband, was accepted into the senatorial class. To 198/200 Avitus was Suffektkonsul . 208-211 he took part in the Emperor's campaign in Britain . Under Severus' son and successor Caracalla , who reigned from 211 to 217, was Avitus first governor of the province Dalmatia , then proconsul of the province of Asia .

Mamaea first married a consular whose name is unknown, then the procurator Gessius Marcianus, who also came from Syria. His hometown was Arca Caesarea, today's Arqa in Lebanon. There she gave birth to her only son Bassianus Alexianus, the future emperor Severus Alexander, on October 1, 208. At that time Gessius Marcianus already had a daughter who was married in 218; possibly it came from a previous marriage of the procurator. Information about another daughter is fictitious. At least for a while Mamaea lived at the court of Emperor Caracalla, who was her cousin as Julia Domna's son.

| Julius Bassianus |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Julius Avitus Alexianus |

Julia Maesa |

Julia Domna |

Septimius Severus 193-211 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Julia Soaemias |

Julia Mamaea |

Geta 211 |

Caracalla 211-217 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Elagabal 218-222 |

Severus Alexander 222-235 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Times of crisis

On April 8, 217, Emperor Caracalla was murdered in Mesopotamia . He was succeeded by his Praetorian prefect Macrinus , who was involved in the murder plot. This meant that the Severan dynasty was initially disempowered. For the Syrian clan to which Mamaea belonged on their mother's side, this resulted in their expulsion from the center of power. Julia Domna took her own life. Mamaea's ambitious mother Maesa had to leave Rome on the orders of the new emperor Macrinus and retire to her Syrian homeland. Avitus, Mamaea's father, died of old age in 217/218. Her husband Gessius Marcianus also probably died during the turmoil of this time of crisis, because nothing more is reported about him in the period that followed.

Since the descendants of Emperor Septimius Severus were now extinct, Maesa wanted to procure her own male descendants the imperial dignity, although she was not related by blood to the dynasty founder Severus, but only by marriage. Her two underage grandchildren came into consideration: Varius Avitus, later known by the nickname Elagabal , whose mother was Mamaea's older sister Julia Soaemias, and Mamaea's son. In order to make her plan plausible, Maesa let the rumor spread among the soldiers stationed near Emesa that their grandchildren were illegitimate children of the Emperor Caracalla, who was very popular with the soldiers. This created the occasion for a military rebellion against the unpopular Macrinus. In May 218, the fourteen-year-old Elagabal was proclaimed emperor by mutinous soldiers. This was the undoing of Mamaea's daughter (or stepdaughter), who was within Macrinus' sphere of influence; the Praetorian prefect Ulpius Julianus had her and her husband killed as soon as he heard of the rebellion. In Rome the Senate declared the leaders of the uprising to be enemies of the state; Mamaea was also mentioned by name.

The uprising spread rapidly. Macrinus, who was in Syria, was defeated on June 8, 218 and killed soon after. Maesa was then able to set off for Rome with her daughters and grandchildren. The journey was slow; Only in the summer of 219 did the family of the new ruler Elagabal arrive in Rome. Maesa took over the reign for the underage Elagabal. From then on Mamaea and her son also lived in the capital of the empire at the imperial court.

Soon the young emperor Elagabal proved to be headstrong and resistant to advice and made himself generally hated. This created a very dangerous crisis that came to a head in 220/221. Therefore Maesa and Mamaea began to build up Mamaea's son as the future successor of his cousin Elagabal. Since the new bearer of hope, like Elagabal, was considered the illegitimate son of Caracalla, he was qualified for the dignity of the emperor in the eyes of the dynastic-minded soldiers who venerated Caracalla. On June 26, 221 Elagabal adopted his cousin, whose claim to his successor was recognized by the award of the Caesar title. At the same time the new Caesar changed his name, from then on he called himself Alexander. When Elagabal saw the danger that threatened him from his cousin, he tried repeatedly to kill him. A struggle for existence developed between the two rivals and their mothers, in which Maesa was on Mamaea's side. Mutinous soldiers, controlled by Mamaea, murdered Julia Soaemias and Elagabal on March 11, 222. Thirteen-year-old Alexander was able to take over the imperial dignity without difficulty.

Role in the reign of Alexander

In contrast to Elagabal, Alexander proved to be insightful and obedient. Mamaea had him brought up carefully. Initially, Maesa and Mamaea ruled together. Pay attention first was the sympathy extraction in the Senate , where Elagabal strongest as provocative behavior perceived irritation was triggered. A senate-friendly course was now demonstratively taken and the appreciation for traditional Roman virtues and values emphasized. The establishment of an advisory committee of sixteen respected senators documented the change of direction. This policy was well received in the Senate; the senator and historian Cassius Dio noted with satisfaction that Mamaea had found clever advisors for her son. She knew how to choose the best advisors from among the senators and then took them into her confidence in all matters.

It is unclear whether Maesa and Mamaea worked together harmoniously or whether there was - as some researchers suspect - a power struggle between a Maesa party and a Mamaea opposing party. If there was a rivalry, it couldn't have lasted long, because Maesa, who was already old at the time, probably died around 224/225. From then on, the power-conscious and assertive Mamaea, who had been Augusta since 222 , led the government alone.

Even after reaching manhood, Alexander remained largely under the influence of his mother. Their continued position of power is impressively documented by inscriptions and coins. Like Julia Domna, she had the honorary titles of “Mother of the Camp” ( mater castrorum ), “Mother of the Senate” and “Mother of the Fatherland”. The official title was extended by overzealous admirers: A Hispanic inscription glorified Mamaea as the mother of the emperor, the camp, the senate, the fatherland and the whole human race, a Thracian even as “mistress of the world”.

But the honors could not hide the fact that Mamaea's power base was very narrow and that her rule was always precarious. Her weakness was drastically evident when her favorite Ulpian lost a deadly power struggle. Ulpian, a prominent lawyer to whom Mamaea had entrusted the high command of the Praetorians , had to flee to the imperial palace during a Praetorian mutiny. Even there Mamaea could not protect him; in her and Alexander's presence, he was murdered by the Praetorians.

Mamaea's attempt to secure the continuation of the dynasty by marrying Alexander ended in complete failure. She chose the patrician Orbiana as wife for her son , but the marriage ended two years later after Mamaea got caught in a power struggle with her daughter-in-law and her father, Seius Sallustius . The conflict led to the dissolution of the marriage in 227 and Orbiana's exile to Africa. Seius Sallustius, who tried to incite the Praetorians against Mamaea, was executed. After this experience, Mamaea did not allow her son to remarry. Apparently she saw in every marriage between the imperial family and a foreign clan a threat to her power. For fear of this risk, however, they jeopardized the continued existence of the dynasty. There was no regulation of the succession until the end of Alexander's reign.

Religious politics

The religious policy of Elagabal, which was offensive to the Romans and who brought the Syrian cult of the sun god to Rome, was reversed immediately after his fall. Mamaea showed tolerance towards the Christians, who had been spared persecution under Elagabal. She is said to have met with the important Christian theologian Origen in Antioch . Hippolytus of Rome , a prominent church father , dedicated a treatise on the resurrection - preserved in fragments - to her . Therefore, Mamaea's closeness to Christianity can be assumed, but she was certainly not Christian in the sense of a consistent confession. Mamaea and Alexander probably tended towards syncretism , the mixing of ideas from different religions, including Christianity. Such an attitude was incompatible with Christianity's claim to exclusivity.

The path to disaster

Alexander saw himself forced to great campaigns. First he had to fend off a dangerous attack by the Persian king Ardaschir I in the east in 232 , then hurry to the Rhine border in the second half of 234 or the beginning of 235 to repel a German invasion. Mamaea was always there and, as always, played an important role. She shied away from the risks of military conflicts and preferred negotiated solutions. She did not understand the wishes of the soldiers, spoiled by Septimius Severus and Caracalla, for gifts of money. She would rather use the funds available on the Germanic campaign to buy peace. This prospect made the soldiers bitter, because they hoped for victory and booty. They hated Mamaea, who they considered stingy, and could count on the new ruler's financial generosity if there was a change of government. Hence a rebellion ensued. Mutinous soldiers raised the officer Maximinus Thrax to the position of anti-emperor. Now the fragility of Alexander's rule came to light dramatically; nobody wanted to fight for him. On the orders of Maximinus, Mamaea and Alexander were murdered in their tent in the field camp near Mogontiacum in March 235 . The place of death vicus Britanniae is identified by some researchers with Mainz-Bretzenheim , but this location is very controversial.

reception

Ancient and Middle Ages

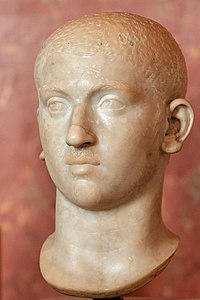

It is unclear whether the new emperor Maximinus had a formal damnatio memoriae imposed on Alexander after the murder of his predecessor and whether such a measure, as is often assumed, also affected Mamaea and other relatives. In the context of such an erasure of memory, it was customary to systematically destroy the portraits of the ostracized persons. There is no evidence in narrative sources, but some portraits of Alexander and his mother were mutilated and their names on some inscriptions deleted. Possibly these were not measures ordered by the state, but rather spontaneous actions. Since a relatively large number of Mamaea's round sculptures - busts and statue heads - have been preserved, systematic destruction does not seem to have occurred.

The sources are unfavorable. The generally reliable contemporary Cassius Dio offers little information about Mamaea, and his history work breaks off even before the start of the Germanic campaign. The main sources are the also contemporary Herodian and the Late Antique Historia Augusta , which are generally considered to be untrustworthy, especially with regard to the depiction of Alexander's reign.

Herodian regarded Alexander's careful upbringing as an essential merit of his mother, but criticized Mamaea as greedy for money and petty and accused her of having prevented decisive action in the Persian War out of cowardice and exaggerated motherly love and thus caused the campaign to fail. His portrayal of Alexander's and Mamaea's downfall can also be classified in this context: shortly before his death, Alexander is said to have clung to his mother and complained lamentably of having caused the disaster. This fictitious dramatic description is the fruit of Herodian's literary creative drive.

The author of the Historia Augusta also portrayed Mamaea as greedy and wrote that Alexander did nothing without her advice. Elsewhere he praised her as an excellent mother. In his portrayal, however, she generally takes a back seat, since the emphasis on her role would have obscured the image of the idealized emperor. The author of the late antique Epitome de Caesaribus also took up the motif of alleged avarice. He told an anecdote about it: Mamaea had forced the emperor to keep leftovers and to eat them at the next meal.

Mamaea's extraordinarily strong influence on her son found an echo in his designation as "Alexander, the son of Mamaea" (Latin Alexander Mamaeae ) in ancient sources. This name was later adopted by Byzantine authors.

Late antique Christian sources emphasized Mamaea's supposed closeness to Christianity. The theologian and historian Orosius even claimed that she was a Christian. Byzantine authors, including Georgios Synkellos and Johannes Zonaras , mentioned her piety and her encounter with Origen.

The medieval Latin-speaking scholars of the West also focused on this aspect. Following Orosius, Mamaea was regarded as a Christian. As one knew of her violent death, the legend handed down by Thomas Ebendorfer arose in the late Middle Ages that she died as a martyr for her faith. According to Ebendorf's account, Alexander killed Mamaea because she professed Christianity. Ebendorfer saw the murder of the emperor in the soldiers' mutiny as a divine punishment for matricide.

Modern

In modern research, Mamaea's efforts to stabilize the empire are recognized, but it is also stated that her attempt at consolidation did not only fail in the final phase of her rule. Alfred Heuss stated that she had managed to “ensure somewhat bearable conditions for twelve years”, but that it was her undoing that she could not deal with the soldiers. Karlheinz Dietz writes that although she had the best of intentions and “moments of stability and continuity” can be seen in her rule, indiscipline and anarchy as symptoms of an internal crisis are characteristic of the years of her exercise of power. Even Karl Christian points to Mamaeas good will, but the fatal lack of military authority had been unable to make up. In spite of positive approaches and “no small achievements”, she did not succeed in consolidating the inner order. The Roman army was in poor shape.

literature

- Bruno Bleckmann : The Severan family and the soldier emperors . In: Hildegard Temporini-Countess Vitzthum (Hrsg.): Die Kaiserinnen Roms . Beck, Munich 2002, ISBN 3-406-49513-3 , pp. 265–339, here: 290–298 (overview)

- Robert Lee Cleve: Severus Alexander and the Severan Women . Los Angeles 1982 (Dissertation, University of California)

- Erich Kettenhofen : The Syrian Augustae in the historical tradition. A contribution to the problem of orientalization . Habelt, Bonn 1979, ISBN 3-7749-1466-4

- Elizabeth Kosmetikatou: The Public Image of Julia Mamaea. An Epigraphic and Numismatic Inquiry . In: Latomus 61, 2002, pp. 398-414

iconography

- Klaus Fittschen , Paul Zanker : Catalog of the Roman portraits in the Capitoline Museums and the other municipal collections of the city of Rome . Volume 3, Philipp von Zabern, Mainz 1983, ISBN 3-8053-0582-6 , text volume pp. 30–33, table volume panels 41–44 (No. 33–35)

- Max Wegner : Iulia Mamaea . In: Heinz Bernhard Wiggers , Max Wegner: Caracalla, Geta, Plautilla. Macrinus to Balbinus (= Max Wegner (Hrsg.): The Roman image of rulers , section 3, volume 1). Gebrüder Mann, Berlin 1971, ISBN 3-7861-2147-8 , pp. 200-217

Web links

- Herbert W. Benario: Short biography (English) at De Imperatoribus Romanis (with references).

- Jona Lendering: Julia Mamaea . In: Livius.org (English)

Remarks

- ↑ On this marriage and on the presumed descent of the late Severi from the Princes of Emesa see Barbara Levick : Julia Domna. Syrian Empress , London 2007, pp. 9f., 13f .; Anthony R. Birley : The African Emperor. Septimius Severus , 2nd, expanded edition, London 1988, p. 222; Richard D. Sullivan: The Dynasty of Emesa . In: Rise and Fall of the Roman World , Vol. II 8, Berlin 1977, pp. 198–219, here: 214; Richard D. Sullivan: Priesthoods of the Eastern Dynastic Aristocracy . In: Sencer Şahin et al. (Ed.): Studies on religion and culture Asia Minor , Vol. 2, Leiden 1978, pp. 914–939, here: 928–930.

- ↑ On the career of Avitus see Helmut Halfmann : Zwei Syrische Relatives des Severischen Kaiserhaus . In: Chiron 12, 1982, pp. 217-235, here: 219-225; Markus Handy: Die Severer und das Heer , Berlin 2009, pp. 50–56; Hans-Georg Pflaum : La carrière de C. Iulius Avitus Alexianus, grand'père de deux empereurs . In: Revue des Études latines 57, 1979 (1980), pp. 298-314.

- ↑ See Cassius Dio 79 (78), 30.3. When specifying some books in this historical work, different counts are used; a different book count is given here and below in brackets. The contemporary Cassius Dio expressly describes Gessius Marcianus as the father of Severus Alexander. Martijn Icks, however, denies the accuracy of this communication: The Crimes of Elagabalus , London 2011, p. 58. He believes that Mamaea's second marriage was concluded in 212 at the earliest and that the father of the future emperor was her first husband.

- ^ Robert Lee Cleve: Severus Alexander and the Severan Women , Los Angeles 1982, pp. 90f.

- ↑ For the dating see Helmut Halfmann: Two Syrian relatives of the Severan imperial family . In: Chiron 12, 1982, pp. 217-235, here: 223.

- ^ Robert Lee Cleve: Severus Alexander and the Severan Women , Los Angeles 1982, pp. 60f.

- ↑ Herodian 5: 3, 10.

- ↑ Cassius Dio 79 (78), 31.4.

- ↑ Cassius Dio 79 (78), 38.1.

- ↑ Robert Lee Cleve provides a detailed account of the processes: Severus Alexander and the Severan Women , Los Angeles 1982, pp. 105–163.

- ↑ a b Herodian 5,7,5.

- ↑ Herodian 6: 1, 2. See Karlheinz Dietz : Senatus contra principem , Munich 1980, pp. 300–305.

- ↑ Cassius Dio, quoted by Johannes Zonaras : Zonaras 12:15; Text and translation by Stephanie Brecht: The Roman Imperial Crisis from its outbreak to its climax in the description of Byzantine authors , Rahden 1999, p. 76f.

- ↑ For the hypothesis of a rivalry, Erich Kettenhofen pleads: Die syrischen Augustae in der historical tradition , Bonn 1979, p. 45. Cf. Fulvio Grosso: Il papiro Oxy. 2565 e gli avvenimenti del 222-224 . In: Atti della Accademia Nazionale dei Lincei , row 8: Rendiconti. Classe di Scienze morali, storiche e filologiche , Vol. 23, 1968, pp. 205-220, here: 207-211. Robert Lee Cleve: Severus Alexander and the Severan Women , Los Angeles 1982, pp. 183, 241f. and Elizabeth Kosmetikatou: The Public Image of Julia Mamaea . In: Latomus 61, 2002, pp. 398-414, here: 400; they assume that the two women are on good terms.

- ↑ For the dating see Erich Kettenhofen: On the date of death Julia Maesas . In: Historia 30, 1981, pp. 244-249; James Frank Gilliam : On Divi under the Severi. In: Jacqueline Bibauw (Ed.): Hommages à Marcel Renard , Vol. 2, Bruxelles 1969, pp. 284–289, here: 285.

- ↑ CIL 02 3413 .

- ↑ On the inscriptions see Erich Kettenhofen: Die syrischen Augustae in der historical Tradition , Bonn 1979, pp. 156–163, on the coins Robert Lee Cleve: Severus Alexander and the Severan Women , Los Angeles 1982, pp. 189–193. Elizabeth Kosmetikatou provides an overall picture: The Public Image of Julia Mamaea. An Epigraphic and Numismatic Inquiry . In: Latomus 61, 2002, pp. 398-414.

- ↑ See for the details Lukas de Blois: Ulpian's Death . In: Pol Defosse (ed.): Hommages à Carl Deroux , Vol. 3, Bruxelles 2003, pp. 135–145; Robert Lee Cleve: Severus Alexander and the Severan Women , Los Angeles 1982, pp. 211-235; Julia Sünskes Thompson: Uprisings and protest actions in the Imperium Romanum , Bonn 1990, pp. 81–83.

- ↑ Matthäus Heil : Severus Alexander und Orbiana offers a detailed investigation . An imperial marriage . In: Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik 135, 2001, pp. 233–248.

- ↑ Eusebius of Caesarea , Church history 6,21,3f. See Enrico dal Covolo: La politica religiosa di Alessandro Severo . In: Salesianum 49, 1987, pp. 359-375, here: 365.

- ^ Enrico dal Covolo: La politica religiosa di Alessandro Severo . In: Salesianum 49, 1987, pp. 359-375, here: p. 361 and note 6.

- ^ Enrico dal Covolo: La politica religiosa di Alessandro Severo . In: Salesianum 49, 1987, pp. 359-375, here: 360-362, 364f.

- ↑ For dating see Michael Peachin: P. Oxy. VI 912 and the Accession of Maximinus Thrax . In: Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik 59, 1985, pp. 75-78.

- ↑ Leonhard Schumacher gave detailed reasons for the identification with Bretzenheim ; see Leonhard Schumacher: The Sicilia in Mainz-Bretzenheim . In: Mainz magazine. Middle Rhine Yearbook for Archeology, Art and History 99, 2004, pp. 1–10 and Leonhard Schumacher: Römische Kaiser in Mainz , Bochum 1982, pp. 89–92 (with compilation and discussion of older literature). Cf. Auguste Jardé: Etudes critiques sur la vie et le règne de Sévère Alexandre , Paris 1925, p. 85 and note 4, p. 86. Note 1. Astrid Böhme-Schönberger argues with great emphasis against localization: Became Alexander Severus murdered in Bretzenheim? In: Mainz magazine. Middle Rhine Yearbook for Archeology, Art and History 99, 2004, pp. 11–16. She follows Ronald Knöchlein: Bretzenheim - Zahlbach - Dalheim. The archaeological evidence up to the Franconian era , Mainz 2009, p. 28 and note 21 and p. 45.

- ↑ One of the researchers who assume a damnatio memoriae Mamaeas is Helmut Halfmann: Two Syrian relatives of the Severan imperial family . In: Chiron 12, 1982, pp. 217-235, here: 225. If necessary, the measure was reversed in 238, in which Maximinus was overthrown. Klaus Fittschen expresses doubts about a formal damnatio memoriae Mamaeas in: Klaus Fittschen, Paul Zanker: Catalog of Roman portraits in the Capitoline Museums and the other municipal collections of the city of Rome , Volume 3 (text volume), Mainz 1983, p. 32. Spontaneous destruction actions without a damnatio memoriae by the Senate suspect Eric R. Varner: Mutilation and Transformation. Damnatio Memoriae and Roman Imperial Portraiture , Leiden 2004, pp. 196–198 and Lee Ann Riccardi: The Mutilation of the Bronze Portrait of a Severan Empress from Sparta: 'Damnatio Memoriae' or Christian Iconoclasm? In: Communications of the German Archaeological Institute, Athenian Department 113, 1998, pp. 259–269, here: 261.

- ↑ For iconography see Max Wegner: Iulia Mamaea . In: Heinz Bernhard Wiggers, Max Wegner: Caracalla, Geta, Plautilla. Macrinus to Balbinus , Berlin 1971, pp. 200-217; Klaus Fittschen, Paul Zanker: Catalog of the Roman portraits in the Capitoline Museums and the other municipal collections of the city of Rome , Volume 3 (text volume), Mainz 1983, pp. 30–33 (No. 33–35).

- ↑ Herodian 6,1,8; 6.8.

- ↑ Herodian 6,5,8f.

- ↑ Herodian 6,9,6.

- ↑ Historia Augusta , Severus Alexander 14.7; 59.8; 60.2. See Elisabeth Wallinger: Die Frauen in der Historia Augusta , Vienna 1990, pp. 105–107, 109f.

- ↑ Historia Augusta , Severus Alexander 66.1.

- ↑ Erich Kettenhofen: The Syrian Augustae in the historical tradition , Bonn 1979, p. 70f.

- ↑ Epitome de Caesaribus 24.5.

- ↑ See e.g. B. Historia Augusta , Severus Alexander 3.1. The sources are compiled by Elizabeth Kosmetikatou: The Public Image of Julia Mamaea . In: Latomus 61, 2002, pp. 398-414, here: pp. 398f. and note 4. See Stephanie Brecht: The Roman Empire Crisis from its outbreak to its climax in the account of Byzantine authors , Rahden 1999, p. 68.

- ^ Enrico dal Covolo: La politica religiosa di Alessandro Severo . In: Salesianum 49, 1987, pp. 359-375, here: 364-368.

- ↑ Orosius 7.18.7 and 7.19.2.

- ↑ Stephanie Brecht: The Roman Empire Crisis from its outbreak to its climax in the account of Byzantine authors , Rahden 1999, pp. 69–81 (compilation of the sources with translation); Enrico dal Covolo: La politica religiosa di Alessandro Severo . In: Salesianum 49, 1987, pp. 359-375, here: 366-368.

- ↑ Thomas Ebendorfer: Chronica regum Romanorum , ed. by Harald Zimmermann , Part 1, Hannover 2003, p. 161.

- ↑ Alfred Heuss: Roman History , Braunschweig 1960, p. 360.

- ^ Karlheinz Dietz: Severus Alexander . In: Manfred Clauss (Ed.): The Roman Emperors. 55 historical portraits from Caesar to Justinian , 4th edition, Munich 2010, pp. 195–202, here: 198.

- ^ Karl Christ: History of the Roman Imperial Era , 6th edition, Munich 2009, pp. 629–632.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Julia Mamaea |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Julia Avita Mamaea |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Mother of the Roman Emperor Severus Alexander |

| DATE OF BIRTH | 2nd century |

| DATE OF DEATH | March 235 |

| Place of death | at Mogontiacum |