Pessimum of the migration period

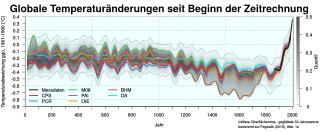

As the pessimum of the migration period or early medieval pessimum (English Migration era pessimum , vandal minimum or dark ages cold period ), climatic conditions in time periods are referred to in various periodizations of climate history , which begin in the range 250 - 450 AD and usually end at around 750 AD .

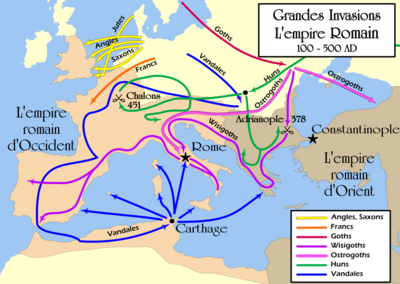

Spatially, this usually means the climatic conditions of the Mediterranean region and Europe, occasionally also Asia, the North Atlantic region or other parts of the world. The name refers to the so-called Migration Period , which mostly falls within these periods. A connection is often made between the changeable or cool climatic conditions and historical processes of that time, such as migration movements, military campaigns and the end of antiquity ( late antiquity ) as well as the fall or transformation of the Roman Empire .

Concept and history of research

Beginning in the 1960s, in the early days of historical climatology , pioneers in this branch, such as Hubert Lamb or Emmanuel Le Roy Ladurie , proposed periodizations of climate history, which they linked to epochs of traditional European historiography.

The climatologist Christian-Dietrich Schönwiese designed such a periodization of the climate history of the Holocene in 1979, drawing on the work of Hubert Lamb and Hermann Flohn .

In it he used the term “pessimum of the migration period” to describe an epoch from 450 to 700 AD as rainy and cool, with widespread glacier advances. He drew parallels with the so-called Great Migration, military campaigns and the capture of Rome in 410.

Schönwiese expressly pointed out that the term “pessimum” should not be misinterpreted in the sense of “globally worse climatic conditions” or as “bad” in a normative sense. In the periodization, as it can be found in Schönwiese, an optimum of the Roman period preceded the pessimum of the migration period. A Medieval Warm Period followed .

In connection with a climatic peak in late antiquity and the early Middle Ages , Lamb's works from 1982 and 1995 are often cited. Lamb combined indications that were supplied by the already existing climate proxies , and derived from this that generally cool and unsteady climatic conditions must have prevailed, especially in Europe, which he roughly classified in the period 400–900. Like Edward Gibbon before him in the 18th century or Ellsworth Huntington and Eduard Brückner at the beginning of the 20th century, he pointed out signs of droughts in the Asian steppe areas, which was a cause for the migration of nomadic groups called " Huns " West could have been.

Initially, primarily historical documents were the basis for discussions about climate fluctuations and their consequences for the Roman Empire. Since the end of the 20th century, more and more paleoclimatological reconstructions have been made, which give a more precise indication of the climate in time. The study of the role of climatic fluctuations in connection with the end of the Roman Empire has gained momentum in recent years, with works from the natural sciences clearly outweighing the historical ones.

Nevertheless, compared to the period from around 800 onwards, the conditions are relatively imprecise. An evaluation of 114 papers published in 2017, which use the English term Dark Ages (Cold) Period , produced a heterogeneous picture: although a little more than half dealt with cooler climates, others also used the term to characterize wetter or drier conditions and wind conditions , other environmental changes, in individual cases for example glacier advances or warmer temperatures. The periods examined ranged from the 1st century BC. BC to the 11th century AD, with a core period between approx. 400 and 800. A uniform, clearly defined meaning has not yet been established.

Historian John Haldon and others noted in 2018 that such a classification of climate history and its consequences, while rhetorical, does not do justice to the complexity of the material available. Such epochs are gradually being abandoned in research.

Climatic conditions

Overview

In the period from about the 1st century BC. Chr. To the 5th century AD, climatically a warm period, the ' optimum of the Roman period '. In the 5th century this warm period was replaced by the 'pessimum of the migration period'. The period from 535–660 AD denotes a climatically cooler epoch in Late Antiquity ( English Late Antique Little Ice Age, LALIA ). Overall, the climate became more humid, the winters colder, there were more storms and floods, which led to land losses on the Atlantic coasts, for example. The alpine glaciers advanced far and also destroyed arable and pasture land, they interrupted transalpine passes. Overall, cultivated land was lost, crop failures occurred and, as a result, supply bottlenecks with famine. Trade routes over highways and their associated settlements over which the exchange of goods took place succumbed. From this developed mass migrations, the migration of peoples , which with other causes then destroyed the Western Roman Empire. The population decreased. Epidemics were favored due to the fragile social organization and the cooler climate . The outbreak of the Justinian plague around 540, which then flared up again and again until 770. Various hypotheses are used to explain, for example the three major volcanic eruptions in AD 536, 540 and 547 (see list of major volcanic eruptions in the time and climate anomaly 536-550 ), whose effects on the climate are still through the retarding effect of the oceans was increased. Feedback effects due to the increased heat absorption in the oceans and the expansion of sea ice ( albedo ) and a minimum of solar activity had a synergistic effect .

Global and Northern Hemisphere

About 5000 years ago, especially in the middle and high latitudes of the northern hemisphere, a long-term cooling trend of a little more than 0.1 ° C per millennium began, which continued into the 19th century and was ended by the current anthropogenic global warming . The cause of the cooling trend are changes in the earth's movement relative to the sun ("orbital radiative forcing ", see Milanković cycles ), which have led to reduced solar radiation in the north. Growing snow and ice cover as well as changes in vegetation make the long-term cooling trend visible, especially in the north , through feedback such as ice-albedo feedback . Fluctuations in solar activity and volcanic eruptions, which temporarily cool the climate, as well as internal variability of the climate system superimpose this long-term trend and lead to regionally differently pronounced climatic fluctuations over a period of years and decades.

The sparse global reconstructions suggest a disruption of the relatively warm conditions from the end of the 5th century AD to around 700 AD, but a clearly distinctly cooler period is globally not discernible. A reconstruction of the temperatures of the last 2000 years north of 30 ° N shows a cooler period in the period 300–800 AD, but the cooling does not come close to that of the Little Ice Age in the 17th century. There is considerable uncertainty about the extent of the fluctuations.

The pessimum has been associated with Bond Event 1 about 1400 years ago. At this time, icebergs in the North Atlantic increasingly transported rock material to the south that could be detected in sediments on the ocean floor .

Europe and the Mediterranean

In Europe, a period of generally cooler summer temperatures between the 4th and 7th centuries can be reconstructed. Overall, the climate became more humid and the winters became cooler. In northern, western and central Europe as well as in the northern Mediterranean region, the cold season was also associated with more humidity. The glaciers grew in the 5th century. The Lower Grindelwald Glacier and other Swiss glaciers were as big as they were at the end of the Little Ice Age . The Roman road through the Val de Bagnes became impassable. The advancement of the glaciers lasted until the 8th century.

For western and central Europe - somewhat the area of what is now northern France, Germany and the British Isles - a synthesis of different climate proxies between the years 250 and 470 showed a tendency towards lower summer temperatures and between 650 and 800 an opposite tendency. For winter temperatures the results were contradicting itself. The reconstruction from proxies, which show year-round temperatures, tended to agree with that of the summer temperatures, although there were considerable uncertainties in the dating. A clear signal of the Late Antique Little Ice Age was just as unrecognizable as a uniform trend in the annual rainfall.

Late Antique Little Ice Age

In addition, around 535/536 there was a short-term strong and global cold anomaly, which is called the Late Antique Little Ice Age (German "small ice age of late antiquity", based on the small ice age of modern times). It is attributed to a catastrophic event, most likely several volcanic eruptions. An extraterrestrial influence, such as comet dust or meteorites, has also been suggested. Several studies published since 2012 indicate that volcanic eruptions through feedback effects, such as ice-albedo feedback , may have contributed significantly to particularly cool climate conditions that lasted for several decades.

trigger

In addition to the volcanic activity, especially in the years 535 and 536, a somewhat weaker radiation from the sun between 400 and 700 may have contributed to climate fluctuations. Reconstructions of solar activity indicate a pronounced minimum in the 7th century.

Changes in the North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO) Changes from 164 to 180, around 400 and from 500 to 600 AD could also have increased droughts on the periphery of the Roman Empire. However, the existing reconstructions of the NAO do not provide a uniform picture.

Historical reports

Wine and grain no longer thrived in northern areas and at high altitudes. Crop failures and susceptibility to disease, infant mortality and the death rate of young children and the elderly increased. Storms and floods resulted in land losses on the North Sea coast and in southern England. There were many floods in Italy in the 6th century.

The Bishop Gregory of Tours reports from the 580s from the Franconian Empire of constant heavy rains, thunderstorms, floods, famines, bad harvests and late cold spells to which birds fell victim. In Norway, 40% of farms were abandoned in the 6th century. The French historian Pierre Riché gives 13 years with famine and floods and nine years with extremely cold winters and epidemics for the period from 793 to 880.

consequences

The suggested periods of a climatic peak include migratory movements and military campaigns from around 375/76 to 568 AD, which are often referred to as " migrations of peoples " (in modern historical and archaeological research, the notion of "migrating peoples" is disproved) and the end or the transformation of the Western Roman Empire accompanied by a demographic crisis . In the 6th century the population of the areas that had previously belonged to the Western Roman Empire declined. In addition to wars, crop failures and epidemics were among the causes. Many villages were abandoned and areas that had previously been used were reforested. By pollen analysis , a general decline of agriculture can be observed. New settlements established in the 7th century show a new settlement structure and demonstrate a cultural break.

For the common population, this phase need not have consistently been associated with poorer living conditions. For example, an increase in body size up to the 6th century speaks for a better protein supply in Northern and Central Europe. However, the regional effects were very different. In the Oder region, for example, almost complete evacuation was established from the middle of the 6th to the 7th century inclusive, which was associated there with arable sites that were generally difficult to cultivate and the strongly continental climatic conditions with particularly drastic climatic fluctuations. In contrast, in the formerly Roman border regions immediately northeast of the Limes, z. B. on the middle Main, a significant increase in population due to phase immigration in the same period based on the increase in corresponding archaeological findings.

Some climate researchers and historians see climatic conditions as a possible partial influencing factor in the historical events and processes of that time. Several avenues of influence have been suggested:

- Vulnerability of agrarian societies to climatic fluctuations,

- the occurrence and spread of epidemics ,

- climate-induced migration movements.

Agricultural Productivity

Henry Diaz and Valerie Trouet point to a possible strong variability of the climate between 250 and 550 AD. Climatic reconstructions from tree rings in the area of today's Germany, France and the Austrian Alps reveal strong hydroclimatic fluctuations over a period of decades. It was difficult for societies to counter such rapid fluctuations with social and technical innovations. The grains of wheat and barley that were widespread at the time were prone to droughts. In addition, they had been displaced by the cultivation of olives and vines on less productive soils. Overall, variations in rainfall and other factors could have severely affected agricultural productivity.

Epidemics

The alternation between dry and very wet decades, combined with deforestation and the development of swamps, could have contributed to the spread of malaria . The disease occurred more frequently in the harvest season in late summer and early autumn. Agricultural workers who fell ill increased agricultural productivity even more.

The leprosy spread at this time in Central Europe. Cooler, wetter climates can make people more likely to contract diseases that are transmitted by droplet infection . These diseases include tuberculosis , leprosy, and smallpox . However, a historically significant connection is not considered to be well established.

The American historian Kyle Harper made connections between the Antonine plague (165-180), the Cyprian plague (250-271) - both probably outbreaks of smallpox - and especially the Justinian plague (probably pulmonary plague ), climatic fluctuations and historical developments. The Justinian plague reached the Egyptian coastal town of Pelusium from north-east Africa in 541 and Constantinople a year later , a few years after the volcanic eruptions in the second half of the 530s. The cool, humid climates of the Late Antique Little Ice Age may have allowed rat fleas , carriers of the plague, and rats to spread. Not only could these pandemics have resulted in labor shortages and economic downturns, but also weakened the Roman military significantly.

Influence on migration

Even Edward Gibbon saw in his published 1776-1789 influential but as outdated applicable historical work The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire climate change as the triggers of migration towards the Roman borders. The German geographer and climatologist Eduard Brückner suspected, after he found evidence of a dry period in Central Asia in the 3rd century, in the 1910s that this could have caused a migration towards Europe. Persistent droughts are still being discussed as a possible reason for the Huns' forays into Europe. These nomadic groups living in the Central Asian steppe regions were likely vulnerable to prolonged droughts and may have been drawn to more fertile pastures in the west. Cold spells and associated famines could also have contributed to the migration.

However, the migration of peoples dragged on for two centuries and began at the time of a climatic optimum. The Swiss climatologist Heinz Wanner , using the terminology of the push-pull model of migration , names population pressure as a possible additional push factor, to which initially climatically favorable phases could have contributed, or as a possible pull factor the customers of more favorable climates - and living conditions elsewhere. Whether climate changes were decisive for the massive migrations of various ethnic groups cannot be conclusively answered.

See also

literature

- Michael McCormick, Ulf Büntgen, Mark A. Cane, Edward R. Cook, Kyle Harper, Peter Huybers, Thomas Litt, Sturt W. Manning, Paul Andrew Mayewski, Alexander FM More, Kurt Nicolussi, Willy Tegel: Climate Change during and after the Roman Empire: Reconstructing the Past from Scientifc and Historical Evidence . In: Journal of Interdisciplinary History . 2012, doi : 10.1162 / JINH_a_00379 ( mitpressjournals.org [PDF; 1000 kB ]).

- Kyle Harper: Climate, Disease and the Fate of Rome . Princeton University Press, 2017, ISBN 978-0-691-16683-4 (see also the critical comments by John Haldon et al .: Plagues, climate change, and the end of an empire: A response to Kyle Harper's The Fate of Rome ( 1) - (3). In: History Compass. 2018).

References and comments

- ↑ Michael J. Decker: Approaches to the environmental history of Late Antiquity, part II: Climate Change and the End of the Roman Empire . In: History Compass . doi : 10.1111 / hic3.12425 . Similarly, Pessimum of the migration time in: Jörg FW Negendank: The Holocene: Considerations with Regard to its Climate and Climate Archives . In: Hubertus Fischer u. a. (Ed.): The Climate in Historical Times . 2004, ISBN 978-3-642-05826-4 , doi : 10.1007 / 978-3-662-10313-5_1 .

- ^ Joel D. Gunn: Introduction: A Perspective from the Humanities-Science Boundary . In: Human Ecology . March 1994, doi : 10.1007 / BF02168760 .

- ↑ a b c d e f g h Samuli Helama, Phil D Jones, Keith R Briffa: Dark Ages Cold Period: A literature review and directions for future research . In: The Holocene . February 2017, doi : 10.1177 / 0959683617693898 .

- ^ A b John Haldon, Hugh Elton, Sabine R. Huebner, Adam Izdebski, Lee Mordechai, Timothy P. Newfield: Plagues, climate change, and the end of an empire: A response to Kyle Harper's The Fate of Rome (1): Climate . In: History Compass . November 2018, doi : 10.1111 / hic3.12508 .

- ↑ Christian-Dietrich Schönwiese: Climate fluctuations (= Understandable Science . Volume 115 ). Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, New York 1979, pp. 75-84 .

- ↑ Christian-Dietrich Schönwiese: Climate changes: data, analyzes, forecasts . Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, New York 1995, ISBN 3-540-59096-X , pp. 79-92 .

- ^ A b Hubert Lamb: Climate, History, and the Modern World . 2nd Edition. Routledge, 1995, ISBN 0-415-12734-3 , pp. 144-154 .

- ↑ Michael McCormick, Ulf Büntgen, Mark A. Cane, Edward R. Cook, Kyle Harper, Peter Huybers, Thomas Litt, Sturt W. Manning, Paul Andrew Mayewski, Alexander FM More, Kurt Nicolussi, Willy Tegel: Climate Change during and after the Roman Empire: Reconstructing the Past from Scientifc and Historical Evidence . In: Journal of Interdisciplinary History . 2012, doi : 10.1162 / JINH_a_00379 .

- ^ A b Michael J. Decker: Approaches to the environmental history of Late Antiquity, Part II: Climate Change and the End of the Roman Empire . In: History Compass . doi : 10.1111 / hic3.12425 .

- ↑ Werner Marx, Robin Haunschild, Lutz Bornmann: Climate and the Decline and Fall of the Western Roman Empire: A Bibliometric View on an Interdisciplinary Approach to Answer a Most Classic Historical Question . In: Climate . 2018, doi : 10.3390 / cli6040090 .

- ↑ Ulf Büntgen, Vladimir S. Myglan, Fredrik Charpentier Ljungqvist, Michael McCormick, Nicola Di Cosmo, Michael Sigl, Johann Jungclaus, Sebastian Wagner, Paul J. Krusic, Jan Esper, Jed O. Kaplan, Michiel AC de Vaan, Jürg Luterbacher, Lukas Wacker, Willy Tegel, Alexander V. Kirdyanov: Cooling and societal change during the Late Antique Little Ice Age from 536 to around 660 AD. Nature Geoscience (2016), Volume 9, pp. 231-236

- ^ PAGES 2k Consortium: Consistent multidecadal variability in global temperature reconstructions and simulations over the Common Era . In: Nature Geoscience . July 24, 2019, doi : 10.1038 / s41561-019-0400-0 .

- ^ Raphael Neukom, Nathan Steiger, Juan José Gómez-Navarro, Jianghao Wang, Johannes P. Werner: No evidence for globally coherent warm and cold periods over the preindustrial Common Era . In: Nature . July 24, 2019, doi : 10.1038 / s41586-019-1401-2 .

- ↑ Information from Paleoclimate Archives: Observed Recent Climate Change in the Context of Interglacial Climate Variability and Regional Changes During the Holocene - Temperature - Northern Hemisphere Mid-to-High Latitudes . In: Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [IPCC] (Ed.): Fifth assessment report (AR5) . 2013, 5, Executive Summary, and 5.5.1.1.

- ↑ Shaun A. Marcott et al. a .: A Reconstruction of Regional and Global Temperature for the Past 11,300 Years . In: Science . tape 339 , March 8, 2013, doi : 10.1126 / science.1228026 .

- ↑ Heinz Wanner , L. Mercolli, M. Grosjean and SP Ritz: Holocene climate variability and change; a data-based review . In: Journal of the Geological Society . 2014, doi : 10.1144 / jgs2013-101 .

- ↑ Fredrik Charpentier Ljungqvist: A new reconstruction of temperature variability in the extra-tropical northern hemisphere during the last two millennia . In: Geografiska Annaler: Series A, Physical Geography . No. 3 , 2010, doi : 10.1111 / j.1468-0459.2010.00399.x .

- ↑ a b Jürg Luterbacher u. a .: European summer temperatures since Roman times . In: Environmental Research Letters . 2016, doi : 10.1088 / 1748-9326 / 11/2/024001 ( HTML ).

- ↑ a b Olga N. Solomina u. a .: Glacier fluctuations during the past 2000 years . In: Quaternary Science Reviews . 2016, doi : 10.1016 / j.quascirev.2016.04.008 .

- ^ Dana FC Riechelmann, Marjolein TIJ Gouw-Bouman: A review of climate reconstructions from terrestrial climate archives covering the first millennium AD in northwestern Europe . In: Quaternary Research . October 2018, doi : 10.1017 / qua.2018.84 .

- ↑ a b Ulf Büntgen u. a .: Cooling and societal change during the Late Antique Little Ice Age from 536 to around 660 AD . In: Nature Geoscience . 2016, doi : 10.1038 / ngeo2652 ( PDF ).

- ↑ Dallas H. Abbott, Dee Breger, Pierre E. Biscaye et al. a .: What caused terrestrial dust loading and climate downturns between AD 533 and 540? In: Geological Society of America Special Papers . No. 505 , 2014, doi : 10.1130 / 2014.2505 (23) .

- ↑ Dallas H. Abbott, SN Martos, H. Elkinton, R. Fleming, A. Garcia, AR Chivas, D. Breger, S. Haslett and MR Kaplan: Did Two Bolide Fragments Strike the Gulf of Carpentaria around 1500 Years Ago? In: AGU Fall Meeting Abstracts . tape 1 , December 2009, p. 1436 .

- ↑ Matthew Toohey et al. a .: Climatic and societal impacts of a volcanic double event at the dawn of the Middle Ages . In: Climatic Change . 2016, doi : 10.1007 / s10584-016-1648-7 .

- ^ B. Lee Drake: Changes in North Atlantic Oscillation drove Population Migrations and the Collapse of the Western Roman Empire . In: Scientific Reports . April 2017, doi : 10.1038 / s41598-017-01289-z .

- ↑ Behringer, 2007, p. 138 "In Norway [...] there are two periods in which around 40% of the farms were abandoned: once in the 6th century [...] and again since 1300 [...]". Behringer names Eva Österberg u. a. "Desertion and land colonization in the Nordic countries c. 1300-1600 ", Almqvist & Wiksell International, 1981, ISBN 9122004319 .

- ^ A b Philipp von Rummel , Hubert Fehr: The migration of people . Theiss, 2011, ISBN 978-3-8062-2283-8 , pp. 9 ff., 164 .

- ↑ Walter Pohl : The migration of people: conquest and integration . W. Kohlhammer, 2002, ISBN 978-3-17-014518-4 .

- ↑ Bernd Zolitschka, Karl-Ernst Behre, Jürgen Schneider: Human and climatic impact on the environment as derived from colluvial, fluvial and lacustrine archives — examples from the Bronze Age to the Migration period, Germany . In: Quaternary Science Reviews . January 2003, doi : 10.1016 / S0277-3791 (02) 00182-8 .

- ↑ a b Wolfgang Behringer: Cultural history of the climate . 2007, p. 92-94 .

- ^ A b Nikola Koepke, Joerg Baten: Climate and its Impact on the Biological Standard of Living in North-East, Center-West and South Europe during the Last 2000 Years . In: History of Meteorology . 2005 ( meteohistory.org [PDF; 117 kB ]).

- ↑ Armin Volkmann: Settlement - Climate - Migrations: Geoarchaeological research on the Oder region between 700 BC and 1000 AD with a focus on the migration period. Studies on the archeology of Europe . Habelt, Frankfurt 2013, ISBN 978-3-7749-3832-8 .

- ^ Christian-Dietrich Schönwiese: Climate changes. Springer, Berlin 1995, pp. 83-86, ISBN 354059096X

- ↑ In historical migration research, possible climatic influences play a minor role: Franz Mauelshagen: Migration and Climate in World History . In: Sam White, Christian Pfister and Franz Mauelshagen (eds.): The Palgrave Handbook of Climate History . palgrave macmillan, ISBN 978-1-137-43019-9 , p. 413 .

- ^ A b c d e Henry Diaz, Valerie Trouet: Some Perspectives on Societal Impacts of Past Climatic Changes . In: History Compass . 2014, doi : 10.1111 / hic3.12140 .

- ↑ a b c d Kyle Harper: Climate, Disease and the Fate of Rome . Princeton University Press, 2017, ISBN 978-0-691-16683-4 .

- ↑ Monica H. Green: Climate and Disease in Medieval Eurasia . In: Oxford Research Encyclopedia Asian History . June 2018, doi : 10.1093 / acrefore / 9780190277727.013.6 .

- ^ Anthony J McMichael: Extreme weather events and infectious disease outbreaks . In: Virulence . July 2015, doi : 10.4161 / 21505594.2014.975022 .

- ^ Franz Mauelshagen: Climate as a Scientific Paradigm - Early History of Climatology . In: Sam White, Christian Pfister , Franz Mauelshagen (Eds.): The Palgrave Handbook of Climate History . palgrave macmillan, 2018, ISBN 978-1-137-43019-9 , p. 579-580 , doi : 10.1057 / 978-1-137-43020-5 .

- ↑ AF: Climatic Variations and Migration in the Ancient World . In: Natural Sciences . tape 4 , no. April 16 , 1916, p. 214–215 , doi : 10.1007 / BF01497640 (reports on a lecture Brückner gave to the annual meeting of the KK Geographical Society in Vienna).

- ↑ Heinz Wanner: Climate and People - A 12,000-year history . Haupt, 2016, ISBN 978-3-258-07879-3 , The European migration of peoples - was the climate involved ?, p. 219-222 .