Arbeia

| South Shields Castle | |

|---|---|

| Alternative name | Arbeia |

| limes | Britain |

| section | Hadrian's Wall |

| Dating (occupancy) | 2nd to early 5th century AD |

| Type |

a) Alen and cohort fort, b) replenishment depot , c) naval base |

| unit |

a) Legio Sextae Victrix Pia Fidelis , b) Ala I Pannoniorum Sabiniana , c) Ala I Hispanorum Asturum , d) Cohors V Gallorum , e) Numerus barcariorum Tigrisiensium |

| size | Area: 2.1 ha |

| Construction | Stone construction |

| State of preservation | The foundations above ground are still visible, reconstruction of the west gate, a barracks and the late antique praetorium |

| place | South Shields |

| Geographical location | 55 ° 0 '15 .9 " N , 1 ° 25' 51.9" W |

| Subsequently | Segedunum Fort (west) |

| Aerial view of the fort area |

|---|

| Webaviation |

|

Link to the picture |

| Model of the fort in the 3rd century |

|---|

| Dave Colthorpe , 2013 |

|

Link to the picture |

Arbeia was an auxiliary troop fort and supply base for the garrisons of Hadrian's Wall ( vallum aelium ). It is located in the municipality ( Parish ) of today's South Shields , District South Tyneside , County Tyne and Wear , England .

Originally built as a cavalry fort, it was in use for around 300 years, secured and controlled one of the most important ports in Roman Britain and later played an important role in supplying the border troops in the north of the island. Some of the fort's buildings were restored or rebuilt in the late 20th and early 21st centuries. These include the west gate, the late antique commandant's house and a team barrack, which were rebuilt on the original foundations.

Surname

The name of the military camp could go back to a unit from the east of the empire stationed here in late antiquity (see also section Garrison). It is first found in the Notitia Dignitatum , where Arbeia is listed between the entries of Verbeia (now Ilkley, West Yorkshire ) and an unknown station called Dictium . According to this theory, Arbeia could be the Latinized form of the place name originally derived from Aramaic: "The place or the castle of the Arabs". Another explanation for the origin of the ancient naming would be the word rapa , Latin for turnip. This was not unusual for Roman settlements and is now considered more plausible by experts than the former theory.

In the past, the fort was equated with the Horrea Classis of the cosmography of Ravenna ; it contains a list of those forts that were laid out as guard and supply bases for the campaigns of Septimius Severus , which he carried out in northern Britain in the early 3rd century. The name means "The warehouses of the fleet", which initially only Arbeia could be considered. The fleet can only have been referring to the Classis Britannica , which almost certainly has a base here. This view is now considered outdated, the fort in Carpow, Scotland, at the mouth of the Tay , is now favored for the Horrea Classis .

A 16th century chronicler, John Leland , later identified Arbeia as the Anglo-Saxon Caer Urfa , arguably a variation of the earlier Roman name. Caer denotes a fortified place in Welsh, this name was often used in early medieval settlements in Britain. The early form of today's place name, Scheles , appears for the first time around 1235. It describes makeshift barracks or simple residential huts, such as those used in B. used by fishermen. Most of these dwellings were found on the opposite bank of the Tyne ( Tinea ), in North Shields.

Research history and range of finds

The first scientific research took place in the 1870s. The modern development was completely removed from the fort area from the 1970s and the area was redesigned into an archaeological park. During the excavations, a carefully paved square from the early days of the fort came to light under the Roman barracks. Below the square, the remains of an Iron Age house came to light, which also documented the long continuity of settlement.

During the excavations, numerous animal bones were also recovered, especially those of ox, sheep, goats and pigs. Bones of red deer, boar and elk were also found; The latter were probably hunted as a recreational sport and should probably also supplement the soldiers' rations. As the fort was near the coast, seafood such as B. oysters, mussels, limpets / periwinkles and Roman snails.

Recently, the archaeologist Nick Hodgson discovered near the fort u. a. the remains of larger transport amphorae, they were probably imported from Italy ( Campania ). One copy was almost completely restored. It reached a height of less than a meter. Amphorae of this type were mostly used to transport wine. They belong to a type that came into use in the middle imperial period (around 250 AD).

development

The fort area has been inhabited since the Mesolithic (8300 BC). During the excavations, weapons and tools made of flint stone, which were probably made by Stone Age hunters, came to light. From the Neolithic (3500–1800 BC) settled farmers settled here who made ceramics and kept pets.

The first verifiable Roman buildings date from the year 125 AD and probably belonged to the civil settlement ( vicus ) that surrounded the fort in an arc from east to west. The stone fort was probably completed under Hadrian around 129 and occupied by auxiliary troops. In 208 Emperor Septimius Severus started a series of costly campaigns that were supposed to finally subdue the warlike and dangerous highland tribes of the Caledonians . This also changed the tasks of the fort crew. The Reiterala was enlisted in the expeditionary army and used in the Scottish campaigns; in their place a cohort of infantry was stationed in Arbeia . Then the base was converted into a replenishment base and enlarged in terms of area. Above all, the favorable location of the fort near the coast, directly on the river bank, was probably decisive for its new function, as the supplies stored here are convenient and cost-saving on the Tyne and its tributaries further inland and to the crews on the Wall ( per lineam valli ) could be transported. At the turn of the 3rd and 4th century the fort burned down and then seems to have been temporarily abandoned. Its revival as a supply base did not begin until the end of the 4th century. Around 400 it was finally abandoned by the army, but continued to be used by the civilian population and probably only abandoned by its last inhabitants in the late 7th century.

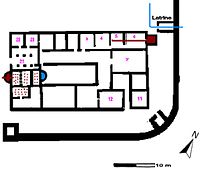

Fort

In Arbeia it was a multiphase Castle, running in the standard design of the 2nd century, d. H. square and with rounded corners (playing card shape). The walls were reinforced by internal towers. The approx. 110 × 180 m measuring fort wall was supported on its back by an earth ramp, which also served as a battlement. 205–207 the fort wall was extended 45 m further to the south, increasing the fenced area from 1.67 to 2.1 hectares.

The fort had a total of four gates secured by two side towers. The water was supplied via an aqueduct , which, according to an inscription, was built around 222. As an additional obstacle to the approach, the fort was surrounded by a double pointed moat. The fort area was divided into four parts by the two main streets of the camp (Via praetoria, Via decumana) . The section of Via praetoria that ran from the south gate to the Principia - the staff building - was paved and flanked on both sides by colonnades. For the paving of the street, stones from demolished buildings (e.g. the Principia) were apparently reused later .

The west gate was rebuilt in 1988. It houses part of the museum and serves as a viewing platform. The reconstruction of the west gate tries to reproduce the appearance of the years around 161-180 as accurately as possible. It is based on architectural remains found on site (e.g. a keystone from one of the archways), the completely preserved foundations, fragments found on the remains of a comparable fort gate in Libya or in the Birdos Forest (window arches), contemporary representations and the results of a functional analysis. The gate was classically designed and flanked by two multi-storey tiled towers, which protruded slightly from the wall at the front. There were two passages between the towers, above the passages was the guardhouse and above it a battlement with battlements.

Interior development

Between 205 and 207, almost all barracks were removed and replaced by Horrea . For the remaining crew, four new barracks (two double and two single barracks, 12 x 40 m) were built in the Praetentura (southern section). The principia were demolished between 286 and 318 and also replaced by warehouses, while the barracks were renovated. In the early 3rd century, a community latrine was built into the earth ramp of the east wall. It resembled the latrine at Housesteads Fort, and the sewage was disposed of via a canal through which fresh water constantly flowed. In the late 3rd or early 4th century, most of the buildings were destroyed by fire. In the course of the reconstruction, a luxurious praetorium was built. The eight southern Horrea were converted back into barracks, two more south of them were completely rebuilt. One of the barracks and large parts of the late antique praetorium were reconstructed on the original foundations in the middle of the 20th and the beginning of the 21st century.

Horrea

Roman warehouses are easy to identify by archaeologists due to their massive construction, and their foundations are among the best preserved in South Shields. In the Hadrianic era, the fort only had a double horreum of type B, which stood free in the middle of the camp - directly next to the west gate. 205-207, most of the barracks were removed under Septimius Severus and replaced by 13 additional, paired, stone-built Horrea . They stood in three parallel rows and took up the entire area of the Praedentura and the median of the camp. Two of them were built directly into the principia that is no longer required. 222–235, eight more Horrea were added to these. Grain for 40,000 men could now be deposited there.

Since grain filled in sacks was mainly stored here, they were equipped with a slightly raised floor that also allowed ventilation and cooling from below through slots on the side of the supporting walls. The floor was supported by a series of parallel, lengthways, lower intermediate walls, which were interrupted at regular intervals to ensure better air circulation. In order to absorb the strong side pressure of the roof, ten support pillars were built on each long side and two on the narrow sides. The foundations were built twice as wide here, creating a small loading ramp, and traces of stone foundations for posts or column bases, which probably supported a canopy, could also be observed.

Principia

The multi-phase command building (size approx. 20 × 25 m) was the administrative and religious center of the fort. Its ground plan corresponded to the typical design of the late 2nd century. The main entrance was in the south, through a walled inner courtyard, which was lined with a portico on the west and east sides , one got to a transverse hall about nine meters high and oriented from west to east. As an inscription from Reculver attests, such halls were called basilica by the Romans . Daylight fell through windows with three iron bars directly under the roof ridge. Research suggests that roll calls and exercises took place there in bad weather or in winter. At the back of the basilica was the square flag shrine ( aedes ), which protruded slightly to the northwest, but, unlike many other comparable buildings of this type and size, did not have a semicircular apse in which the standard of the occupation troops and an imperial statue were usually placed were. Often the flag sanctuary had a cellar because the troop treasury was also kept there. To the west and east of the flag sanctuary there were still two rooms each that could have served either as writing rooms or armories. In the early 3rd century the building was demolished and replaced by two warehouses.

Praetorium

The Praetorium of Arbeia is one of the best known in Roman Britain. It was excavated by Paul Bidwell and Nicholas Hodgson from the Tyne and Wear Museum, and the reconstruction of the house from 2000 is based on their results and interpretations. This luxuriously furnished peristyle house of the fort commandant dates back to late antiquity and - unusual for Roman castles - was not built in the center of the fort, but in the south-east corner of the fort. Presumably it was commissioned by the commander of the Syrian unit. Judging by the style and layout of the house, he was a man from Roman culture and not a barbarian.

The main entrance was in the west, you first entered an elaborately decorated hall (room 21, or atrium ). A small corner room, room 22, was probably the porter's office. Room 23 was probably a small office ( officium ), where less important visitors were received. In the center of the atrium was a stone-lined shaft in which valuables or the like may once have been stored. The central courtyard was surrounded on two sides by a column-supported portico . The camp commandant's private apartments were on the left. They consisted of rooms 3, 4, 5 and 6, which were connected by doors. 5 and 6 could also be heated by a central prefurnium .

At the other end of the inner courtyard was the large triclinium (dining room, room 7), which, however, could not be heated. Room 12 was much smaller, but probably also served as a dining room, in contrast to room 7 it had underfloor heating ( hypocausts ) and was probably only used in the cold season. At the western end of the house, right next to the entrance, there was a small but well-equipped bathroom ( thermal bath ) .

Rooms 8, 9 and 11 probably housed the kitchen and storage room - a door led from here directly to the inner Wallstrasse (via sagularis) . In room 13 there was a storage room and the praefurnium - from where the hypocausts were fired. A latrine was also built into one corner. This was followed by room 14, it was paved with coarse stones and equipped with a drainage channel, possibly a cattle shed once housed here.

garrison

According to some inscriptions, members of the Legio Sexta Victrix Pia Fidelis were among the first to occupy the fort as part of their work as a building vexillation. However, it seems rather unlikely that members of the Legion were stationed here permanently after the fort was completed. The expansion of the stone fort required specialized craftsmen, who were usually only to be found among the legions and not among the auxiliaries who were later garrisoned here. The legions were responsible for building most of the empire's military structures, including the Arbeia Castle . After their withdrawal, the legionaries were replaced by auxiliary units.

The following auxiliary units are known or may have been crewed for Arbeia for a limited time:

| Time position | Troop name | description |

|---|---|---|

| 2nd century AD | Legio sextae Victrix (the sixth legion, the victorious), | One of their vexillations was probably stationed here until the construction work was completed. An altar donated by Centurion Julius Verax suggests that a construction team of at least one centurion strength was constantly in the camp during the construction phase . |

| late 2nd century AD |

Ala prima Pannoniorum Sabiniana ("the first Pannonian cavalry squadron of Sabinus") |

This riding troop originally came from what is now Hungary. According to a tombstone inscription, she may have been stationed in Aldeia Nova ( Portugal ) before. The unit was eventually posted to Britain, where it remained until the late 2nd century. Its nickname suggests that its first commander / recruiter was called Sabinianus. From Savaria (Szombathely, HU) an inscription is known that names the prefect Titus Cnoris Sabinianus, who commanded a lancer unit there. The unit was probably relocated to Onnum Castle (now Halton Chesters / Northumberland) before the beginning of the 3rd century . |

| early 2nd century AD |

Ala prima Hispanorum Asturum ("the first squadron of Hispanic Asturians ") |

The second cavalry unit stationed in Arbeia was recruited from the Asturian tribe in northern Spain and probably came to the island around 43 with Claudius' invading army . So far it is only known from an inscription on a tombstone. |

| early 3rd century AD |

Cohors V Gallorum ("the fifth cohort of the Gauls ") |

The riders were replaced under Septimius Severus by a 1,000-strong infantry unit, which was probably withdrawn from the Cramond fort on the Firth of Forth for this purpose . The presence of the Gauls in Arbeia is confirmed by a consecration stone and the inscription of an aqueduct, which was discovered in 1985. Normally, a cohors milliara used around ten barracks as accommodation, but it seems that the actual strength of the Gaulish cohort was only slightly less than half, around four centuries are likely to have remained in Cramond. The remainder are believed to have been used as escorts to guard the supplies between South Shields and Cramond. |

| 4th to 5th century AD |

Numerus Barcariorum Tigrisiensium ("a group of freighters from the Tigris") |

After the military reforms of Diocletian and Constantine I , the garrisons on the Wall were part of the limitanei . The last demonstrable Roman occupation unit for Arbeia consisted of a unit of men from the Tigris region in the Middle East, who were under the command of a prefect. It is only mentioned in the Notitia Dignitatum, in the list of troops of the Dux Britanniarum . This unit was likely engaged in transportation across the Tyne Estuary and on the coast. Other Barcarii units in the empire also had such duties to perform. The name of one of her relatives is also known from a tombstone for his late wife from Arbeia . It was Regina, an indigenous British woman from the Catuvellauni tribe , who lived mainly in southern Britain - in the region around Hertford, Northampton, Buckingham, Bedford and Cambridge. Her husband, Barates, was from the city of Palmyra in the province of Syria , it is very likely that he ended up in Britain as a soldier in the Roman service and was stationed in Arbeia in the 4th century . Presumably he is identical to the Barates, whose tombstone is preserved in Coria / Corbridge . |

| 2nd to 5th century AD | Classis Britannica (the British fleet) | It is not known whether there were also naval units stationed in the port of the fort, but it is likely due to the location and function of the fort. On the occasion of his visit to the island in 122, Emperor Hadrian had the fortifications everywhere renewed or new structures built. Members of the fleet also took part in the largest of these projects, Hadrian's Wall. In the years 208 to 210 Emperor Septimius Severus led a campaign against the Caledonians in northern Scotland. The Classis Britannica supported the land army by securing its flanks from the sea and organizing the transport of supplies. |

Hints

The site is now looked after by the Tyne and Wear Museums / Arbeia Roman Fort and Museum. A small permanent exhibition on the history of the fort is housed in the rebuilt west gate, and from the top floor one has a good overview of the excavation site. Some of the foundations of the fortifications, the interior construction, the replica of the west gate and a barracks can still be seen today. In 2000 the late antique praetorium (commandant's house) was reconstructed using the latest excavation findings. The small museum in the west gate mainly shows models of the fort in its various expansion phases and the principia as well as Roman grave finds and utensils and documents the everyday life of the auxiliary soldiers stationed in Arbeia . One of the most remarkable finds in the exhibition is the remains of a Roman chain mail that was recovered from a well.

literature

- John N. Dore, John P. Gillam: The Roman fort at South Shields, Excavations 1875–1975 , Monography 1, Society of Antiquaries of Newcastle upon Tyne 1979.

- Ronald Embleton, Frank Graham: Hadrian's Wall in the Days of the Romans . Newcastle 1984, ISBN 0859831779 , pp. 33-42.

- RW Davies: The Roman Military Diet . In Britannia 2, 1971, pp. 122-142.

- Robin George Collingwood, Richard Pearson Wright (Shepard Frere and Roger Tomlin eds.): The Roman Inscriptions of Britain . Oxford 1965, ISBN 0862998204

- Anne Johnson : Roman forts of the 1st and 2nd centuries AD in Britain and in the Germanic provinces of the Roman Empire . Zabern, Mainz 1987, ISBN 3-8053-0868-X ( Cultural History of the Ancient World , Vol. 37).

- JH Corbitt: The South Shields Roman Gold and Silver Hoard. Article in: South Shields Archaeological and Historical Society Papers, 1, 1955.

Remarks

- ↑ Science-Technology, Archeology, Beer Despiser from Rome , Der Spiegel 45/2011, p. 142.

- ^ Anne Johnson : 1987, p. 172.

- ^ Anne Johnson: 1987, p. 178.

- ^ Anne Johnson: 1987, p. 171, Margot Klee, 2006, p. 31.

- ^ AE 1962, 258

- ↑ Leg. VI vic. > Paterni “The VI. victorious legion, the Century of Paternus [built this]. ”( The Roman Inscriptions of Britain [RIB] 1070a; Jo0a; l of Roman Studies (JRS) 52 (1962), p. 193, no. 13).

- ↑ Leg. VI vic. …>… Severi p. CII “The VI. victorious Legion, […] the Century of […] Severus, [built this] 102 feet [of the earth ramp]. ”(RIB 1070d; Britannia 18 (1987), p. 368, no. 8).

- ↑ Leg. VI vic. pf coh. III>… “The VI. victorious legion, loyal and conscientious, the III. Cohorte, the Century of [... built this]. ”(RIB 1070e; Britannia 16 (1995), pp. 379 f., No. 6).

- ^ Iulius Verax> Leg. VI "Julius Verax, centurion of the VI. Legion [donated this]. ”(RIB 1057; altar stone).

- ↑ D (is) M (anibus) Victoris natione Maurum / [a] nnorum XX libertus Numeriani / [e] q (u) itis ala (e) I Asturum qui / piantissime pr [ose] qutus est “To the spirits of the deceased for Victor, from the Moorish nation, 20 years old, freedman of Numerianus, soldier of the First Ala the Asturians, executed in humility [his grave monument] ”(RIB 1064; tombstone).

- ↑ … [ac c] astr (orum) [ac senat (us) ac] / [pa] tria [e pro pietate] / [a] c dev [otione] / [com] muni c [urante] / [[[ C (aio) Iul (io) Marco]]] l [eg (ato) Aug (usti) pr (o) pr (aetore)] / [coh (ors)] V Ga [ll (orum) pos (uit)] “[For Julia Domna, mother of Augustus], of the camp, the Senate and the fatherland, the loyalty and devotion of the community, under the administration of Gaius Iulius Marcus, Legatus pro praetore of the Emperor, the 5th cohort of Gauls has this Stone set. ”(RIB 1070b; Britannia 16 (1985), pp. 325-326, no. 11). For the interpretation of this text cf. also the inscription from Risingham / Northumberland (RIB 1235; approx. 209 AD).

- ↑ Imp (erator) Caes (ar) divi Severi / nepos divi magni Antonini fil (ius) / M (arcus) Aurel (ius) Severus Alexander / Pius Felix Aug (ustus) pontif (ex) max (imus) / trib (unicia ) pot (estate) p (ater) p (atriae) co (n) s (ul) aquam / usibus mil (itum) coh (ortis) V Gallo (rum) in / duxit curante Mario Valeriano / leg (ato) eius pr (o) pr (aetore) "The emperor Caesar Marcus Aurelius Severus [Alexander] Pius Felix Augustus, grandson of the deified Severus, son of the deified Antoninus the great, chief priest, with tribunician power, father of the fatherland, consul, donated this water pipe for the soldiers of the 5th Gallic Cohort, on the instructions of Marius Valerianus, his Legatus pro praetore ”(RIB 1060; foundation inscription of the aqueduct of Arbeia, around 222).

- ↑ Praefectus numeri barcariorum Tigrisiensium, Arbeia “The prefect of the number of the freighters from the Tigris in Arbeia” (Notitia Dignitatum XL, 22).

- ↑ D (is) M (anibus) Regina (m) liberta (m) et coniuge (m) / Barat (h) es Palmyrenus natione / Catuallauna an (norum) XXX // Palmy… “To the spirits of the dead for Regina, a freedwoman and wife of the Barates from Palmyra, Catuvellaunerin, she was 30 years old. ”(RIB 1065; tombstone).

RIB = Roman Inscriptions in Britain

Web links

- Arbeia Castle on Historic England Past Scape

- Arbeia Roman Fort & Museum

- Website with numerous pictures of the fort

- Earthwatch Institute (excavation reports for the past 10 years)

- Hadrian's Wall photo album on Flickr

- Satellite photo of the fort area, location of Roman monuments on Vici.org.

- The wall from Arbeia to Maia. Film production with 3D-CGI models, images and explanation of the individual Roman castles along Hadrian's Wall, Part I on You Tube.

- Arbeia on Roman Britain

- John Collingwood Bruce: The Roman Wall: A Description of the Mural Barrier of the North of England, 1867, with numerous pictures of wall remains, altars, inscriptions etc.