Regulbium Castle

| Fort Reculver | |

|---|---|

| Alternative name |

a) Regulbium , b) Regulbio |

| limes | Britain |

| section | Litus saxonicum |

| Dating (occupancy) | 1st to 5th century AD |

| Type |

a) cohort fort , b) fleet station ? |

| unit |

a) Cohors I Baetasiorum , b) Classis Britannica ? |

| size | approx. 3.6 ha |

| Construction |

a) wood and earth fort, b) stone fort |

| State of preservation | Square complex with rounded corners, remnants of the south and east walls still visible above ground, northwest side washed away |

| place | Herne Bay / Reculver |

| Geographical location | 51 ° 22 '45.6 " N , 1 ° 11' 59.5" E |

| Previous | Fort Othona to the northwest |

| Subsequently | Rutupiae fort to the southeast |

Regulbium was part of the chain of castles on the British Saxon Coast (SK) in England , on the northern coast of the county of Kent , District City of Canterbury near the former Reculver , a village that had been settled since the 19th century and largely disappeared due to coastal erosion, two kilometers east of Herne Bay .

Its remains were first mentioned in writing in the 19th century and were uncovered by archaeologists between 1952 and 1968. As the only one of the Saxon coastal fortifications, a building inscription was found there, which enabled the fort to be precisely dated. From the 3rd century it was integrated into the chain of castles of the Litus Saxonicum ( Saxon coast ). The fort area, in the Middle Ages u. a. also built over with a monastery, was largely lost at the beginning of the 19th century due to coastal erosion . Today only a few remains of the fort's wall and the ruins of St. Mary's Church can be seen.

Surname

The name of the fort comes from the Celtic and means "at the headland" or "large headland". So far it is only known from the Notitia Dignitatum (ND) (Regulbio) . In Old English it became Raculf , sometimes Raculfceastre . This is how today's Reculver developed . Reculver is in the early Middle Ages, in a document from the year 669, as Raculfmynster and in a document of 784, as Raculfceaster referred. Raculfceastre contains the Old English ceaster (English: chester ), which often refers to a Roman settlement or enclosed city. In the Anglo-Saxon chronicle of the 12th century, the place appears again as Raculf .

location

The coastline has changed a lot since late antiquity and today's landscape - or "the great peninsula" - has little in common with that of Roman times. Thanet was still an island separated from the mainland by the Wantsum Canal . At that time the fort stood about one kilometer from the coast, on the so-called Thanet Beds, whose sandy, loam-strewn soil was eroded very quickly by the surf and in the course of time has already carried half the fort into the sea. The mainland north of the fortification has almost completely disappeared today. The Wantsum Canal, on the other hand, has almost completely silted up over time. The fort stood on a low hill on the extreme northeastern tip of Kent. From there you had a good view of the surrounding area and the coast on all sides.

development

24 coins from the time of Tiberius and Nero indicate that the site has been used by the Romans since the 1st century. The Romans probably landed part of their invading army here in 43 AD and then built a small wood and earth fort into a fortified bridgehead. Then a road was laid to Canterbury , about 13.7 km southwest, which proves the presence of the Romans in Reculver from that point on. The base was later used as a beacon and signaling station because it was conveniently located on the banks of the Wantsum Canal and near the mouths of the Thames and the Medway . The stone fort was founded at the end of the 2nd or early 3rd century. This assumption is based mainly on an inscription tablet from the flag shrine (see below). The date of the inscription in the early 3rd century also coincides with the finds (including the ceramics) that were made mainly in 1957, but also in later excavations around the fort.

Regulbium secured the northern entrance to the canal, which at that time was still a busy shipping passage, and thus also the Thames estuary, which is important for shipping . Its southern end was guarded by the garrison of Rutupiae fort . It probably also served as a port and supply base for the canal fleet . During the existence of the British special empire, it was probably also the task of the occupation to defend this section of the coast against an invasion of the Roman central government.

Due to the increasing threat from Saxon and Frankish pirates from the continent, Carausius , founder and ruler ( usurper ) of the so-called "British Sonderreich", reorganized the defense of the British Channel coast around the year 287. By building new or converting existing systems, he and his successor Allectus gradually created a dense chain of partly. strongly fortified forts, in which Regulbium was also included. The fort was then occupied by the Roman army for about 150 years . The finds from the fort area also show that at the end of the 3rd century there were major building activities, the cause of which was probably the raids by Saxon pirates and looters on the British Channel coast. Shortly after its completion, the fort was apparently abandoned, but how long it stood empty is unknown.

Around 100 coins from the period from 270 to 300 were recovered in the vicinity of two excavated barracks in the northern sector. According to the excavator, this may be related to the temporary absence of the garrison and the associated deterioration of the barracks . It is possible that the fort was not occupied again by Constantius I until 296, after the fall of the British special empire (see Carausius ) . From the first half of the 4th century onwards, military activities decrease noticeably. The coin finds also showed that the fort was apparently abandoned by the military after 360 and either left to the civilian population or to new settlers or immigrants.

After withdrawal of the Romans, the fort served as a temporary residence of the Anglo-Saxon kings of Kent, one of them, I Ecgberht , let u here. a. build a church. In 669 Ecgberht awarded the land near Reculver to a clergyman named Bass, who founded a monastery there. In 679 King Hlothhere transferred lands at Westanae ( Isle of Thanet ), in Sturry (near Canterbury) and the monastery of Reculver to the abbot Beorhtwald . This Benedictine abbey later became known as St. Mary's Church of Reculver; its characteristic twin towers (long an important landmark for navigation in the canal) were built in the 12th century.

Fort

The fort was first mentioned in the 19th century by Charles Roach. Brian Philp's archaeologists were able to differentiate between several construction phases in the fort based on the excavation results in the 1960s.

Wood and earth fort

Its east and south sides could be located between 1961 and 1963 within what would later become the Saxon Coast Fort. The east side of the Claudian wood-earth fort was heavily overlaid by what was later to become the building. It was surrounded by two weir trenches, the inner y- and the outer v-shaped. The outer moat was apparently already neglected in ancient times and no longer cleaned regularly, which is why it was partially filled with clay deposits and mud that contained ceramic shards from different time periods. The ditch ran even further northwest, so that the excavators assumed that the north wall was to be found under a group of country houses, a late antique thermal baths and a medieval cemetery.

Stone fort

There is not much to see of this fort today, only the remains of the south and east walls, which are heavily overgrown with vegetation, can still be seen. Of these, the south wall was best preserved. It is connected to the east wall by a rounded corner, the two defensive ditches in front of which can also be seen to some extent. This type of construction is typical of forts from the early 3rd century, most of which were still built in the traditional style of the early and middle Imperial Era (playing card shape).

Fence and ditches

The fence was originally about 4.5 m high, 3 m thick at the base and tapered up to 2.4 m. Originally it probably comprised an area of approx. 3.06 hectares. At its core, it consists of black flint ( flint stone ), which is, u. a. on the island of Thanet was broken, and silica sandstone. Further building material for the fort was apparently brought in from the area around Bishopstone Glen (between Reculver and Herne Bay). The silica sandstone probably comes from the Maidstone region. The walls were originally clad with limestone blocks ("ragstone") on their front and back . Little of it has survived to this day. Most of the time, only the wall core is visible, some of which have been preserved up to a height of 2.6 m. The northern wall, along with parts of the eastern and most of the western wall, fell into the sea over the centuries as a result of the undercutting of the terrain. Subsequent repairs can still be seen on the east wall. The remains of a kiln were also found there. An earth ramp backfilled to the rear stabilized the relatively narrow circular wall and also served as a battlement. The fort was destroyed in the course of time by stone robbery, here in particular the southwest corner. In the ruins of the Marienkirche there are a large number of Roman bricks that still come from the fort buildings.

In addition, two pointed trenches surrounded the fort, the inner one was 2.7 m deep and 7.9 m wide, the outer one was approx. 2 × 5 m deep.

Towers and gates

The entrance to the camp headquarters was on the north side, which indicates that the main gate ( porta praetoria ) of the fort was also on the north fence, opposite the headland and the coast. There was also a gate in the middle of the west and east walls. The approx. 2.7 m wide passage of the east gate led to the former main camp road ( via principalis ). After passing the gate you can still see the heavily overgrown foundations of a guard house on the right side. Only a single tower attached to the inside could be detected in the south-west corner. Since no protruding U-towers - typical of late antiquity - could be identified, it is almost certainly one of the earliest stone forts on the Saxon coast , next to the one in Branchaster .

Interior constructions

During the excavation in September 1968, the main focus was on the grid squares east of the Principia , the staff building, and south of the Via principalis , which once connected the two gates on the flanks of the fort inside the camp. However, due to the already very advanced erosion of the coast, not much can be said about the interior development.

The remains of the Principia were found with a flag sanctuary with a basement (Aedes principiorum) , the foundations of a transverse hall (basilica) , walls of the commandant's house (praetorium) and a bathing building with hypocaust heating and a double barracks. Numerous discoveries were also made during engraving along the gravel remains of the Via principalis , Via praetoria and Via sagularis . The principia , built in stone, were located in the central area of the fort in the classical manner. These building structures were found by archaeologists together with presumed officers' quarters, barracks and a bathhouse . A Roman oven, which was found 61 m southeast of the camp, was probably used to dry grain and fish. Its combustion chamber measured approximately 4.9 mx 4.8 m.

In the first half of the 4th century, most of the interior development was likely to have consisted of wooden buildings, as post holes could be detected in the fire layer of the western barracks that did not follow the previous building scheme.

Building SW

When the fortification of the stone fort was erected, plans were also made to build a larger building in the SW sector of the camp. Its foundations consisted of several pounded layers of pebbles that were apparently collected on the beaches in the vicinity. Later its SE corner and the west wall could also be examined. No evidence could be found that the building was ever completed or that it had gone beyond the foundation stage. Brian Philp assumes that this circumstance is connected with a temporary abandonment of the fort, for which other findings from the interior of the camp also speak.

Barracks

The original plan must have been changed afterwards, as two larger buildings have now been erected in the north sector. The floors of these buildings consisted of a layer of rammed earth, over which a wooden grate anchored in the solid foundations was placed to fix the floor boards. The walls of at least one of the two barracks were plastered and painted, the roof covered with heavy tiles. Apparently they served as crew quarters for higher ranks or specialists, since they were in the immediate vicinity of the Principia . The barracks to the east had obviously already fallen into disrepair when it was finally burned down (perhaps by new settlers).

Signal station

A square structure just outside the fort probably served as a signal station or possibly also as a lighthouse. It stood at the northern entrance to the Wantsum Canal and thus underlines the great importance of this waterway for the supplies of the Roman army in Britain. Finds that could confirm its unequivocal chronological classification were not recovered, but coins found on site from the reigns of Tiberius and Nero suggest that a military station had existed here since 65 AD at the latest.

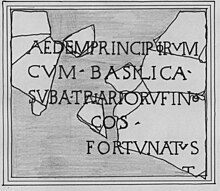

Building inscription

The Roman inscription plaque from Reculver is one of the most remarkable finds on the Saxon coast, as it is the only one known so far to prove the construction work on a fort on the Wash-Solent-Limes . It is generally regarded as the building inscription of the fort, but it only reports on the completion of the commandant's office, one of the fort's most important functional buildings. The first of the eleven fragments of the building inscription was discovered in September 1960 under the flag shrine of the Principia . Her letters were originally painted in red. It was probably attached to the front wall of the sacellum before it fell into the basement of the flag shrine when the building was destroyed. After comparing and composing the fragments, Ian Archibald Richmond was able to reconstruct about ¾ of the original text:

" Aedem p [rinci] piorum / cu [mb] asilica / su [b A (ulo) Triar] io Rufino / co (n) s (ulari)) / [--- Fo] rtunatus / [---] it

The flag shrine with the transverse hall, under Aulus Triarius Rufinus, consul (ar) [...] Fortunatus [...] donated this. "

According to his interpretation of the text, the Principia , the flag sanctuary (Aedes principiorum) and the transverse hall (basilica) in front of the sanctuary were built under the government of the governor Triarius Rufinus. The work was supervised by a certain Fortunatus, probably the commanding officer of the fort at the time. Triarius Rufinus was Consul of the year 210, and Richmond believes he took office as British governor sometime between 210 and 216.

Richard Harper and the latest edition in the corpus of British inscriptions, however, are of the opinion that the governor named in the inscription is Quintus Aradius Rufinus , who presumably held this office around 220 (see below [b A] r [ad] io Rufino) . It is also worth mentioning that this text is the earliest known text in which the terms Aedes principiorum are used for the flag sanctuary and basilica for a military hall.

“This [was] the first time the inscribed phrase aedes principiorum [could] be ... identified with the official shrine of [a Roman military] headquarters building, hitherto unmentioned in any inscription ... [It was] also the first certain ... application of the name basilica to [this element of the building]. " (Eng .: " This [was] the first time that the engraved word sequence aedes principiorum (...), which has not yet been mentioned in any inscription had been identified (...) at an official shrine [of a Roman military] headquarters. [It was] also the first safe (...) use of the name basilica for [this building element]. " )

- - Ian Richmond : The Antiquaries Journal . 1961. , cited in

garrison

| Time position | Troop name | description | Illustration |

| 4th to 5th century AD | Cohors prima Baetasiorum (the first cohort of the Baetasii ) | The occupation troops who probably built the fort are only known for this location from the Notitia Dignitatum and from brick stamps. According to the ND, this cohort - which was under the command of a tribune and belonged to the army of the Comes litoris Saxonici per Britanniam - performed guard duty in Regulbium in late antiquity . Presumably she had been stationed in Britain since the early Imperial Era. It was a cohors peditata quingenaria , d. H. an infantry unit with a nominal strength of 500 men. Their relatives were originally recruited from the Lower Germanic Baetasii tribe - who populated the areas between the mouths of the Meuse and Rhine . The administrative center of their territory was the legionary camp Novaesium , today the city of Neuss in Germany. In addition to Regulbium , the unity could also be proven by means of inscriptions in the bases of Maryport, Alauna , on the west coast of Cumbria , on Hadrian's Wall (late 2nd century) and in Bar Hill on Antonine Wall from the time of the second occupation of the wall (under Septimius Severus ). | |

| 3rd to 5th century AD | Classis Britannica | Marines and crews from the Canal Fleet were probably stationed here as well, who were probably used as coast guards and repel pirates and looters from the Frisian Islands and the North Sea. A total of six roof tiles stamped with the letters CIB were recovered in Reculver. |

port

The location of the quays has remained unknown to date. No remains could be found. It is believed that the port was on the east or south side of the fort.

Civil settlement

Traces of a civilian settlement could also be found around the fort. The camp village ( vicus ) was on the north and west side of the camp. Most of the area was washed away by the sea. It is likely to have been a larger settlement, the built-up area of which covered several hectares of land. In 1936, RF Jessup observed a Roman building with a hypocaust and a paved floor that stood north of the fort. This building was in 17./18. Century also described by John Battely. Presumably the remains of an extramural bathhouse that was built in the early days of the fort. Battely also reported on "several cisterns ", between 3.0 and 3.7 m² in size, covered with oak planks and sealed with clay at the bottom . In his opinion, they were used to store rainwater. In a similar cistern a Roman Strigilis was found , as it was used in bathhouses. Battely therefore suspected: "... since so many [cisterns] would have been discovered that - at least we think so - this proves that the former inhabitants of this place were very numerous." In the 20th century a total of twelve of these Roman wells were built , ten of them with rectangular shafts, proven west of the fort. All had been driven into the hard sandstone layers under the softer sandstone of the Thanet Beds in order to reach the water table. The Roman found layers of the vicus extend up to 340 m west of the fort and date from the period between 170 and 360, which roughly corresponds to the useful life of the fort.

Children's skeletons

The remains of ten children's corpses were discovered in the storage area, all of whom died in infancy. Five of the skeletons were found in the foundations of buildings or their walls, along with coins from AD 270-360. It was assumed that more such finds would be made in the buildings in the southwestern area of the fort if there were more in the future Excavation to be carried out. The babies were probably buried there as part of a sacrificial ritual . Today it is no longer possible to determine whether they were already dead - possibly even stillbirths - when they were buried there, whether they were still buried alive or killed for the sacrificial ritual.

Hints

The more than 24,000 small finds from the fort area and its surroundings are kept in the Herne Bay Museum and Dover Castle. The fort area is under the protection of the English Heritage .

literature

- Robin G. Collingwood : The Archeology of Roman Britain . Methuen, London 1930,

- Alec Detsicas: Peoples of Roman Britain / The Cantiaci . A. Sutton, Gloucester 1983,

- Nick Fields: Rome's Saxon Shore Coastal Defenses of Roman Britain AD 250-500 . Osprey Books, December 2006 (Fortress 56),

- James Ingram: The Saxon Chronicle, AD 1 to AD 1154 . In: Rhys (Ernest) Everyman's Library, 1912,

- David E. Johnston (Ed.): The Saxon Shore . The Council for British Archeology, 1977 (Research Report No. 18),

- Anthony David Mills: Oxford Dictionary of English Place-Names , Oxford University Press, 1998,

- Brian J. Philp: Report on the Excavations of Roman Reculver, with main contributions by Richard Reece, Joanna Bird, Kay Hartley . Kent Archaeological Rescue Unit, 2005,

- Brian J. Philp: The Reculver Inscription , Kent Archaeological Review 1969, No. 17,

- Brian J. Philp: The Excavation of the Roman Fort at Reculver, Kent . Kent Archaeological Rescue Unit, 2005. ISBN 0-947831-24-X . Pp. 98, 102, 192-193.

- Brian J. Philp: The Roman Fort at Reculver Excavations 1968 - Interim Report. . In: Kent Archaeological Review . No. 15, 1969. Retrieved January 21, 2011.

Remarks

- ↑ B. Cunliffe: CBA Report No. 18, 1977, p. 1.

- ↑ A.Mills 1998th

- ↑ Anno Domini DCCLXXXIV: Ego Ealmundus Rex Cantiæ do tibi, Wihtrede, honorabili Abbati, tuæque familiæ degenti in loco qui dicitur Raculfcester, terram 12 aratorum quæ dicitur Sildunk. I Ealmund, King of the Cantiaci, obey Wihtrede, the most honorable abbot, and his family from the town of Raculfcester, 12 Hufen of the land that is called Sildunk.

- ↑ 669: that year King Egbert gave a preacher, Bass, Raculf to build a monastery here. 690: that year Archbishop Theodore, who was bishop for 22 winters, died, he was buried in the city of Cantwanbyrig ( Canterbury ). Bertwald, who was previously Abbot of Raculf, followed him on the calendar of July.

- ^ E. Ekwall: The Concise Oxford Dictionary of English Place-Names . 4. Offsets. Oxford University Press, Oxford 1960. ISBN 978-0-19-869103-7 . P. 383.

- ^ AD Mills: A Dictionary of English Place-Names . Oxford University Press, Oxford 1998. ISBN 978-0-19-280074-9 . P. 285.

- ^ J. Glover: The Place Names of Kent . Batsford, 1976. ISBN 978-0-7134-3069-1 . P. 155.

- ^ RF Jessup: Reculver in Antiquity . Issue 10th issue 38 (1936). ISSN 0003-598X . P. 190.

- ↑ There are many other Old English forms of this name.

- ^ E. Ekwall: The Concise Oxford Dictionary of English Place-Names . 4. Offsets. Oxford University Press, Oxford 1960. ISBN 978-0-19-869103-7 . P. 92, panel XXVII.

- ^ A b R. F. Jessup: Reculver in Antiquity . Issue 10th issue 38 (1936). ISSN 0003-598X . P. 188.

- ^ S. Bagshaw: History, Gazetteer & Directory of Kent . Bagshaw. 1847. Retrieved September 25, 2015.

- ^ RF Jessup: Reculver in Antiquity . Issue 10th issue 38 (1936). ISSN 0003-598X . Pp. 190-191.

- ^ A b B. Philp: The Excavation of the Roman Fort at Reculver, Kent . Kent Archaeological Rescue Unit, 2005. ISBN 0-947831-24-X . P. 3.

- ↑ Arch.Cant. , LXXIII, 1959, p. 96.

- ↑ Barry Cunliffe, CBA Res. Report 1977, p. 3.

- ^ B. Philp, 1968, p. 4

- ^ A b J. Cotterill: Saxon raiding and the role of the Late Roman coastal forts of Britain in Britannia . Issue 24 (1993). ISSN 1753-5352 . Pp. 227-239.

- ^ A b B. Philp: The Excavation of the Roman Fort at Reculver, Kent . Kent Archaeological Rescue Unit, 2005. ISBN 0-947831-24-X . Pp. 227-228.

- ↑ Anglo-Saxon Chronicle for the year 669 online in Project Gutenberg (English)

- ↑ http://www.anglo-saxons.net/hwaet/?do=get&type=charter&id=8 S8

- ↑ Census 2001 . (2001). Office for National Statistics .

- ↑ Philp 1969, p. 18 f.

- ^ B. Philp: The Excavation of the Roman Fort at Reculver, Kent . Kent Archaeological Rescue Unit, 2005. ISBN 0-947831-24-X . P. 14.

- ^ T. Wilmott: Richborough and Reculver . English Heritage, London 2012. ISBN 978-1-84802-073-3 . P. 20.

- ^ B. Philp: The Excavation of the Roman Fort at Reculver, Kent . Kent Archaeological Rescue Unit, 2005. ISBN 0-947831-24-X . Pp. 15, 32-36.

- ^ B. Philp: The Excavation of the Roman Fort at Reculver, Kent . Kent Archaeological Rescue Unit, 2005. ISBN 0-947831-24-X . Pp. 14, 204.

- ↑ Building blocks from the fort were probably used in the medieval settlement of Reculver as well as for the church there. They will also have been used for the medieval Ford Palace , owned by the Archbishop of Canterbury, about 4.2 km southwest of Reculver, and for the Davis Gate (or Barbican Gate ) in Sandwich in the early 16th century. And there are records of their frequent use in the Church of All Saints at Birchington-on-Sea until at least 1584.

- ↑ Helen Clarke et al. a. (Editor): Sandwich: The 'Completest Medieval Town in England' . Oxbow, 2010. ISBN 978-1-84217-400-5 . P. 159.

- ^ JP Barrett: A History of the Ville of Birchington . 3. Edition. Michael's Bookshop, 2005 (1893). ISBN 1-905477-16-3 . Pp. 32-32.

- ^ B. Philp: The Excavation of the Roman Fort at Reculver, Kent . Kent Archaeological Rescue Unit, 2005. ISBN 0-947831-24-X . Pp. 14-15.

- ^ S. Harris: Richborough and Reculver . English Heritage, London 2001. ISBN 978-1-85074-765-9 . P. 33.

- ↑ B. Cunliffe, CBA Res. Report, 1977, p. 3.

- ^ B. Philp 1996.

- ^ B. Philp: The Excavation of the Roman Fort at Reculver, Kent . Kent Archaeological Rescue Unit, 2005. ISBN 0-947831-24-X . Pp. 54-59, 60-63, 73-80.

- ↑ A reconstruction of the fort is illustrated in Richborough and Reculver by T. Wilmott.

- ^ T. Wilmott: Richborough and Reculver . English Heritage, London 2012. ISBN 978-1-84802-073-3 . P. 23.

- ^ B. Philp: The Excavation of the Roman Fort at Reculver, Kent . Kent Archaeological Rescue Unit, 2005. ISBN 0-947831-24-X . Pp. 92-95.

- ↑ B.Philp, 1968, p 4

- ^ B. Philp, 1968, p. 4

- ^ I. Richmond, in: Antiquaries Journal , Volume XLI, 1961, p. 224.

- ^ B. Philp: The Excavation of the Roman Fort at Reculver, Kent . Kent Archaeological Rescue Unit, 2005. ISBN 0-947831-24-X . Pp. 206-218.

- ↑ a b B. Philp: The Roman fort at Reculver excavations 1968 - Interim Report . Pp. 7-11. 1969b.

- ↑ a b B. Philp: The Reculver inscription . 1969a. Archived from the original on July 18, 2011. Retrieved September 25, 2015.

- ↑ Past Cape: Regulbium . English Heritage. 2007. Retrieved September 25, 2015.

- ^ AE 1962, 258 .

- ^ RP Harper, in: Anatolian Studies XIV, 1964, p. 163.

- ^ RSO Tomlin, RP Wright, MWC Hassall: Roman inscriptions in Britain . Volume 3: Inscriptions on stone, found or notified between 1 January 1955 and 31 December 2006 . Oxbow Books, Oxford 2009, ISBN 9781842173688 , No. 3027.

- ^ IA Richmond: A New Building-Inscription from the Saxon-Shore Fort at Reculver, Kent in The Antiquaries Journal . Book 41 (3-4). Pp. 224-228.

- ^ B. Philp: The Excavation of the Roman Fort at Reculver, Kent . Kent Archaeological Rescue Unit, 2005. ISBN 0-947831-24-X . P. 212.

- ↑ Notitia Dignitatum XXVIII.18; Tribunus cohortis primae Baetasiorum, Regulbio "The tribune of the first cohort of Baetasians in Regulbio."

- ↑ M. W. C. Hassall: The hist. Background a. milit. units of the SK, CBA Res. Report 1977, p. 9.

- ^ Roman inscriptions in Britain 830, 837 f., 842 f.

- ^ David Breeze and Brian Dobson, 1969–70, Finding an altar stone at Old Kilpatrick, in: Britannia 1 (1970), p. 310 f.

- ^ B. Philp: The Excavation of the Roman Fort at Reculver, Kent . Kent Archaeological Rescue Unit, 2005. ISBN 0-947831-24-X . Pp. 224-225.

- ^ S. Harris: Richborough and Reculver . English Heritage, London 2001. ISBN 978-1-85074-765-9 . P. 32.

- ↑ Evidence shows that [most of the Saxon coastal fort] was built around 225–290, which means the system was devised some 60 years before historical records mention Germanic raids. This discrepancy cannot be explained if one understands the fort as a specially built defense system, but an explanation can be provided that it was a number of state shipping centers. Saxon raiding and the role of the Late Roman coastal forts of Britain by J. Cotterill and The Excavation of the Roman Fort at Reculver, Kent by B. Philp establish a direct connection between the Cohors I Baetasiorum and the Classis Britannica in Regulbium and this could be an indication that they both shared the fort.

- ^ J. Cotterill: Saxon raiding and the role of the Late Roman coastal forts of Britain in Britannia . Issue 24 (1993). ISSN 1753-5352 . P. 238.

- ^ B. Philp: The Excavation of the Roman Fort at Reculver, Kent . Kent Archaeological Rescue Unit, 2005. ISBN 0-947831-24-X . P. 229.

- ^ B. Philp: The Excavation of the Roman Fort at Reculver, Kent . Kent Archaeological Rescue Unit, 2005. ISBN 0-947831-24-X . Pp. 95-97.

- ^ B. Philp: Excavations at eht Visitors Center, Reculver, Kent 2008-9 in Kent Archaeological Review . Issue 178 (2009). ISSN 0023-0014 . P. 174.

- ^ J. Duncombe: The Antiquities of Richborough and Reculver Abridged from the Latin of Mr. Archdeacon Battely . Johnson. Pp. 56-57. 1774. Retrieved September 25, 2015.

- ^ A b c B. Philp: The Excavation of the Roman Fort at Reculver, Kent . Kent Archaeological Rescue Unit, 2005. ISBN 0-947831-24-X . P. 96.

- ^ J. Duncombe: The Antiquities of Richborough and Reculver Abridged from the Latin of Mr. Archdeacon Battely . Johnson. Pp. 57-60, 116. 1774. Retrieved September 25, 2015.

- ^ B. Philp: The Excavation of the Roman Fort at Reculver, Kent . Kent Archaeological Rescue Unit, 2005. ISBN 0-947831-24-X . Pp. 95-96.

- ↑ Three female skeletons were found in Roman wells, complete with their jewelry: “[It] seems clear that these female skeletons did not come from ritual burials, nor were they accident victims. It is likely that the three women were victims of violence and their bodies (...) were thrown into these (...) wells and were never recovered. "

- ^ B. Philp: The Excavation of the Roman Fort at Reculver, Kent . Kent Archaeological Rescue Unit, 2005. ISBN 0-947831-24-X . Pp. 75-77, 86-87, 225.

- ↑ B. Philp: Ritual burials at Reculver . 1966. Archived from the original on July 18, 2011. Retrieved September 25, 2015.

- ^ R. Merrifield: The Archeology of Ritual and Magic . Batsford, 1987. ISBN 978-0-7134-4870-2 . Pp. 50-57.

- ↑ Three children's skeletons in the buildings in the southwestern area of the fort were found by chance in only two critical cuts made through the building walls, and at least statistically it can be assumed that more will be found in the much longer, as yet unexplored walls. Two of the three bodies can be seen in The Excavation or the Roman Fort at Reculver, Kent by B. Philp, Plate XXXVIII.

- ^ B. Philp: The Excavation of the Roman Fort at Reculver, Kent . Kent Archaeological Rescue Unit, 2005. ISBN 0-947831-24-X . P. 86.

- ^ B. Philp: The Excavation of the Roman Fort at Reculver, Kent . Kent Archaeological Rescue Unit, 2005. ISBN 0-947831-24-X . Plate XXXVIII.

- ^ B. Philp: The Excavation of the Roman Fort at Reculver, Kent . Kent Archaeological Rescue Unit, 2005. ISBN 0-947831-24-X . P. 225.

- ^ R. Merrifield: The Archeology of Ritual and Magic . Batsford, 1987. ISBN 978-0-7134-4870-2 . P. 51.

- ↑ "The Romans officially condemned human sacrifice (...) human lives were cheap at the border and Roman auxiliaries could be as barbaric as those they fought (...) Even in the most civilized parts of Roman Britain, the authorities occasionally seem to oppose child sacrifice to have been blind, which of course happened in secret. ”from: The Archeology of Ritual and Magic by R. Merrifield.

Web links

- Regulbium on "Roman Britain"

- Reculver Saxon Shore fort on Historic England

- Aerial view of the fort area

- Reconstruction of the fort

- Reconstruction of the command building

- Map of the Wantsum Canal in Roman times

- Reculver Towers and Roman Fort . English Heritage.

- Reculver Visitor Center and Country Park . Kent Wildlife Trust.

- Regulbium . English Heritage.

- Regulbium on Castles | Forts | Battles