Novaesium

| Novaesium | |

|---|---|

| Alternative name | Castrum Novaesium Castra Novaesia (pl.) |

| limes | Lower Germanic Limes |

| Dating (occupancy) | A) 20/15 to around 10 BC Chr. B) 12/9 v. To 14 AD C) 14 AD D) Tiberian E) early Iberian F) early Iberian to 43 G.1) 43 to around 50 G.2) around 50 to 69/70 G.3) 70 to Mid-90 or up to 103/104 H) mid-2nd century up to 256/257 or up to 275/276 |

| Type | A) Vexillation camp B) Double legion camp C) Four legion camp D) Auxiliary camp E) Legion camp (?) F) Legion and auxiliary camp G) Legion camp H) Alen camp |

| unit | A) Unknown Vexillatio B) Legio XIX and Legio XVII or Legio XVIII C) Legio I Germanica , Legio V Alaudae , Legio XX Valeria Victrix and Legio XXI Rapax D) Unknown Cohort or Ala E) Unknown Unit F) Legio XX Valeria Victrix + Cohors III Lusitanorum + Ala Parthorum Veterana G.1−2) Legio XVI Gallica + Ala Gallorum Picentiana G.3) Legio VI Victrix H) Ala Afrorum veterana (?) |

| size | A) 13−14 ha B) 660 × 800 m = over 50 ha C) over 80 ha D) 180/200 × 140/180 m = 2.5−3.5 ha E) over 40 ha F) 22−26 ha G) 420 × 570 m = 24 ha H) 165 × 178 m = 2.9 ha |

| Construction | AB) Earth fort or wood-earth camp C-G.2) Wood-earth camp G.3-H) Stone fort |

| State of preservation | invisible soil monuments |

| place | Neuss - Gnadental (Neuss) |

| Geographical location | 51 ° 11 '2 " N , 6 ° 43' 19" E |

| Previous | Gelduba (north-northwest) |

| Subsequently | Small fort on Reckberg , Durnomagus (both south-southeast) |

Novaesium , the former Neuss legionary camp (also Castrum Novaesium , plural Castra Novaesia ), in the Gnadental district of Neuss, is one of the most important and best-researched Roman military camps in the Rhineland . Furthermore, today's ground monument is considered the oldest known military camp of its kind in this region. During the time of its existence, Novaesium was next to Vetera and Mogontiacum the most important deployment base of the Romans in their attempt to occupy the Germania magna , and then formed an essential part of the Lower Germanic Limes . In provincial Roman archeology , the reconstruction of Novaesium was considered ideal for decades for Roman legionary camps of the imperial era.

location

The area of the Neuss military camp is located immediately northwest of the mouth of the Erft , about 2.5 kilometers southeast of today's city of Neuss. In ancient times, due to the topographical conditions, the square was ideal as a garrison location. In this region, the expanding Cologne Bay to Lower Rhine Valley . From a strategic point of view, the site was chosen in a favorable way, as it was possible to intervene quickly in the area of the Wupper , Düssel and Ruhr estuaries . The estuary area of the Ruhr in the area of Duisburg , which was additionally secured by the opposite auxiliary camps Asciburgium ( Moers- Asberg) and Gelduba ( Krefeld - Gellep-Stratum ), probably received special attention . There an important older trade and military route, the later Hellweg , met the Rhine from the east .

The Neuss garrison square took on a strategic key position in the history of Roman Germania on the left bank of the Rhine, initially as the base of operations for the Roman offensives against the Germanic peoples before and shortly after the turn of the century. Later it became an important part of the Lower Germanic Limes, which was defensively oriented to secure the province of Germania inferior until the fourth century AD.

The immediate location of the camps was protected by natural obstacles. The Rhine did not bend to the north at this point as it does today, but continued straight ahead for a good three kilometers in a north-westerly direction, only to swivel to the north-east again in the area of today's Neuss Rhine port. In this way he created an obstacle to approaching the praetorial fronts of the Neuss camps. The Erft formed a certain flank protection to the south-east and the then still marshy “Meertal” to the north-west, a valley that is now built on.

In today's settlement topography nothing can be seen of the former garrison above ground. Only a “historical tour” with copies of large Roman artefacts and various signs and information boards as well as the findings of a Roman cult site (so-called Fossa Sanguinis ) preserved in situ and provided with a protective structure refer to the ancient Novaesium .

Ancient sources and etymology

The place name Novaesium was first mentioned in the Historien (Historiae) of Tacitus . In these descriptions the garrison of the place played an inglorious role in the time of the Batavian uprising of Julius Civilis and the turmoil of the four-emperor year 68/69 AD.

The place is also mentioned by the ancient geographers. The Roman geographer Claudius Ptolemy (85–165 AD?), Who lives in Alexandria, lists Hyphegesis Novaesium in his work Geographike , but incorrectly relocates it far east into Germania magna . In the Tabula Peutingeriana , the place name appears, changed in the spelling by medieval copyists in Novesio , between Asciburgium in the north and the Colonia Claudia Ara Agrippinensium in the south, around 34 km from the first and around 39 km from the second. In late antiquity , Novaesium is mentioned in connection with the campaigns of Flavius Claudius Iulianus, the later emperor Julian , around the year 358 by Ammianus Marcellinus , before the ancient name as Nivisium castellum is mentioned for the last time by Gregory of Tours in the Historia Francorum (story the Franconia) is mentioned in connection with a Roman campaign against the Franks around the year 388.

The origin of the name Novaesium is not entirely clear. It appears to be a Latin-Celtic compound, which may have been Latinized to the original Celtic name of the Erft or another local body of water.

Historical background

Occupation time

Following Gaius Iulius Caesar's Gallic War (58 to 51/50 BC), a population vacuum, which was not harmless for the Romans, was created on the Lower Rhine. In particular, Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa tried during his governorship in Gaul (39/38 BC and 20 to 18 BC) to fill this vacuum by resettling Germanic tribes, building administrative structures and building a network of trunk roads. At that time, the Rhine was still seen as the border of the Roman sphere of interest. The main focus was on securing and developing the areas conquered by Caesar. A further expansion policy was not yet on the agenda, the legions were distributed deep in the Gallic hinterland.

This state of affairs changed due to increasing and ongoing encroachments by Germanic tribes on the left bank of the Rhine, which culminated in the so-called Clades Lolliana . In this battle in 17 or 16 BC The Roman governor Marcus Lollius was defeated by a united force of the Sugambri , Tenkerites and Usipeters . The political and propaganda damage seems to have been greater than the actual military consequences and led to a fundamental change in the Roman policy on Germania. Augustus came in the year 16 BC. Chr. Personally to Gaul to finally settle the "Germanic question". He stayed for three years and judged - after he had defeated the Raeter and pacified the area between the Alps and the Danube - from 15 BC. The deployment of the Lower Germanic army from anew.

The Rhine line lost its formerly rather defensive character and became an offensive deployment base against the Germanic areas east of the river. The troops released after the Alpine campaign were relocated to the Rhine, and the Noviomagus legionary camps near Nijmegen and Vetera near Xanten were set up. Whether the more offensive orientation of the Germania policy at this point in time actually aimed at the occupation of Germania on the right bank of the Rhine up to the Elbe, as had long been suspected, is doubted in recent literature.

When Augustus in 13 BC When he returned to Rome, he handed over the supreme command to his stepson Drusus , whose name for the large-scale offensive against the Teutons in the years 12–9 BC. Chr. Stands. In the context of this so-called Drusus offensive, Novaesium probably served as an operational and / or logistical base for the campaigns into Germania on the right bank of the Rhine. Drusus led a total of four campaigns there, with the main activities shifting to the area of chatting in the course of the conflict . After his early death, the campaigns of Tiberius (9–6 BC), Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus (around the year 3 BC), Marcus Vinicius (around the turn of the ages) and from the year 4 AD again continued by Tiberius.

In the spring of 6 AD, however, the operations had to be broken off because an uprising in the province of Pannonia required the presence of the general and part of the legions there. His successor as governor, Publius Quinctilius Varus (7-9 AD) proved a less fortunate hand, which in 9 AD led to the Clades Variana , the so-called "Battle in the Teutoburg Forest", which led to the complete Annihilation of three legions, three ales, and six cohorts ended. In the period that followed, the Romans evacuated all garrisons on the right bank of the Rhine and significantly reduced their ambitions towards Germania. Under Tiberius, who had rushed back to the Rhine, the expansion and consolidation of the river border were now in the foreground. The number of legions on the Rhine was increased from six to eight.

After Tiberius returned to Rome in 12 AD, Germanicus took over command of the Rhineland the following year. He prepared further offensives in Germania on the right bank of the Rhine, but first had to put down a mutiny of the Rhenish legions in AD 14, which had risen against his successor Tiberius after the death of Augustus. Legions I and XX from the Apud Aram Ubiorum legionary camp as well as the V and XXI legions from Vetera were involved in this mutiny , which at that time were in a summer camp in finibus Ubiorum (“in the Ubier area”, probably in the so-called “Camp C. “In Novaesium ). Then began the large-scale and complex forays into Germania magna. Here Germanicus led the southern wing of the Roman army, operating from Mogontiacum ( Mainz ), while Aulus Caecina Severus was in command of the northern army group operating from Vetera .

After the expensive campaigns had not achieved the desired success up to 16 AD, Tiberius broke off the offensive and ordered Germanicus back to Rome. In the period that followed, the Lower Rhine remained a defensive border. At this border, and thus also in Novaesium , it remained relatively peaceful for over half a century. The time of Claudius was primarily characterized by the expansion of the road network that connected the various military camps in the Rhineland. This calm situation only changed with the events of 69/70 AD , which were to shake the entire empire.

Four imperial year and the Batavian uprising

After decades of relative calm, the Rhineland was the region of the empire that was most heavily involved in events during the four-emperor years, alongside the Italian motherland. Galba , Nero's successor , brought the Lower Germanic army against them through some unpopular personnel decisions, which in turn proclaimed Vitellius emperor in January 69 AD . In order to assert his claim to the throne in Rome, Vitellius marched with large parts of the army in two pillars to Italy. Legionnaires from Novaesium were among them . A total of around 70,000 men were withdrawn from the western provinces and military districts, severely exposing the border security.

After the initial successes of Vitellius, who had prevailed against Galba and his immediate successor, Otho , eight Batavian cohorts (around 4,000 men) were ordered back to the Germanic border. They moved into quarters at Mogontiacum in the summer of 69 . At about the same time, Titus Flavius Vespasianus was proclaimed as emperor against Vitellius in the east of the empire, in the provinces of Aegyptus , Syria and Iudaea and in the Danube regions ; his troops marched towards Rome.

When Vitellius then carried out levies in the tribal areas of the Batavians and the Cananefates, which they perceived as arbitrary, in order to strengthen his associations for the impending conflict with Vespasian, the Batavians and Cananefates rose up together with the Frisians under the leadership of the Batavian nobleman and commanding officer Batavian cohort Iulius Civilis . At first, Civilis cleverly gave the appearance of intervening on the side of Vespasian against Vitellius in the civil war.

The uprising gained momentum when, in late summer / early autumn AD 69, the eight Batavian cohorts stationed in Mogontiacum marched north and joined forces with the Civilis. A relief army for the veteran of soldiers of the Legio XXII Primigenia under the command of Gaius Dillius Vocula , which had meanwhile been included by the insurgents, was marched from the south and united in Novaesium with the Legio XVI Gallica . However, it did not dare to penetrate any further into the area around Vetera , but set up camp near Gelduba . Meanwhile, the Army of the Civilis increased incessantly with influx from almost all regions of Germania and began to devastate the areas of the Morin , Menapier , Ubier and Treverer, i.e. the entire Rhineland down to the Moselle and across to the North Sea coast.

Around this time in northern Italy at the Battle of Bedriacum on October 24, 69 the decision between Vitellius and Vespasian was made in favor of the Flavians. The news of this, as well as Vespasian's request to Civilis to end the fighting activities, should have reached the Lower Rhine at the beginning of November of that year. However, it was ignored by the Batavian, who instead sent part of his troops against Vocula. Vocula defeated the troops raised against him and marched on Vetera , whom he was able to temporarily relieve, until the end of December 69 Civilis enclosed the camp again. Vocula then withdrew to Novaesium and was pursued by Civilis, who captured Gelduba and whose cavalry advanced to Novaesium . In the following months, the main events of the war shifted deeper into the south of the Rhineland, where some Gallic tribes, including the Treveri, rose against Vespasian's rule together with the Vitellian legions.

From the Flavians to the end of the Novaesium garrison

Vespasian sent an expeditionary force of nine legions to Germania. The plans to recapture the Rhenish territories had been worked out by Gaius Licinius Mucianus and were successfully executed by Appius Annius Gallus on the Upper Rhine and Quintus Petillius Cerialis on the Lower Rhine. After a final battle in the autumn of 1970, the fighting finally ended in a negotiated peace. Due to the behavior of most of the Rhenish units during the conflicts, the Rhenish army districts were completely reorganized. Novaesium was affected by these restructuring measures insofar as the Legio XVI Gallica was replaced by the Legio VI Victrix , which rebuilt the stone warehouse that had been destroyed during the war. With the exception of two events, things remained relatively quiet in the Rhineland during the Flavian period. Around 77/78 Gaius Rutilius Gallicus led a campaign against the Brukterer with the participation of the Legio VI , in the course of which the seer Veleda was captured. During the Saturninus uprising against Domitian in 89, the legion remained on the side of the emperor and was possibly involved in the suppression of the uprising by the Lower Germanic legate Aulus Bucius Lappius Maximus . The construction of the small fort on the Reckberg fell in the last years of Domitian.

During the era of the adoptive emperors , the Rhine border remained peaceful and the Germania inferior province began to flourish economically. If Trajan initially took over the deployment to the Lower German Army as it had existed since the Flavians, he soon reduced the number of legions on the Lower Rhine from four to three ( Bonna , Vetera and Noviomagus ) and at the latest from around 104 to just two more ( Bonna and Vetera ). In this context, Novaesium was abandoned as a legionary camp by 103/104 at the latest and only occupied by an auxiliary unit. The Germania Inferior was completely spared from the Marcomann Wars , which severely affected Upper Germany and Raetia , and the later Emperor Clodius Albinus easily coped with a minor German invasion . The benevolent policies of the Severans towards their troops ensured increasing prosperity for the legionaries and auxiliaries in the border provinces. In contrast to Upper Germany , the Germania Inferior was not directly affected by the first appearance of the Alamanni , but had troop contingents to provide for Caracalla's counter-offensive in 213. With the Numbers , a new type of service was used for the first time. Germanic attacks on the Lower Rhine area may already have taken place under Caracalla's immediate successors, Elagabal and Severus Alexander , but the Rhineland was by far not as affected as the Germania superior by the first great Alemannic invasion in 233.

When Valerianus withdrew troops from the Rhine and Danube for his campaigns against the Sassanids and thus exposed the defense of the local limits, this naturally did not remain hidden from the Teutons for long. In 254 in Raetia , 259 in Upper Germany again the Alamanni and from 256/257 in the north the Franks crossed the imperial borders for the first time . The son and co-regent of Valerianus and later Emperor Gallienus hurried to the Rhine and brought reinforcements from Britain. Gallienus reformed the army and paved the way for the later differentiation into border troops ( Limitanei ) and movement armies ( Comitatenses ), as the lesson had been drawn from the Germanic invasions that the broken-in Germanic people hardly encountered any resistance once the Limes line itself was broken. From a revolt of the year 259 that originated Gallic Empire of Marcus Cassianius Latinius Postumus , temporarily Iberian, Gallic and Britannic provinces were detached from the empire by the. The Imperium Galliarum lasted 14 years and was involved in heavy defensive battles on the Germanic border from the very beginning. However, it was possible to keep the limits. In the year 273 the Sonderreich was peacefully re-integrated into the Roman Empire. Only a short time later there were renewed Germanic attacks on the empire and in 276 a Frankish breakthrough of catastrophic severity. At the latest (if not 256/257) the last military camp of Novaesium seems to have been destroyed.

Research history

A few Roman finds from Neuss have come down to us as early as the 16th and 17th centuries. Greater interest in the Roman relics and systematic research did not develop until the 19th century, and not only in Neuss. In 1820 the "Royal Prussian Museum of Patriotic Antiquities in the Rhenish-Westphalian Provinces" was founded in Bonn, from which the Rheinisches Landesmuseum Bonn was later to develop. In 1839 the Neusser Altertumsverein was formed, which initiated the first excavations and from whose collections the first Neuss museum developed in 1845. In 1841 the " Society of Friends of Antiquity in the Rhineland " was founded in Bonn , and since 1842 it has published the groundbreaking Bonn yearbooks .

The “father” of the systematic archaeological excavations was to become Constantin Koenen (1854–1929), who had set himself the goal of finding the military camp described by Tacitus. In 1886 he found what he was looking for for the first time during an exploratory excavation and from 1887 to 1900 he carried out the extensive excavation of the legionary fort, later named "Koenenlager" in literature, and published the extensive results in 1904 in the Bonn yearbooks .

After this pioneering act, things became quieter around Novaesium for a quarter of a century. Further investigations were only carried out in the 1920s, again by Constantin Koenen. Even at that time he believed there were well-founded indications of further, older Roman military settlements immediately northwest of the camp he had discovered, but was unable to assert himself with this hypothesis in the professional world until his death.

After the excavation work was interrupted by the Second World War , archaeological research was resumed in 1955 under the direction of Harald von Petrikovits and Gustav Müller (since 1957). They lasted uninterrupted until 1972. In the course of these excavations, Koenen's assumption was confirmed in an impressive way. A total of eight different camps of different times could be identified, furthermore the canabae legionis , the civilian settlements in front of the legionary camps, as well as numerous graves. The results have so far been published in nine monographs on individual find complexes in the “Limes Research” series of the Roman-Germanic Commission of the German Archaeological Institute , but an overall presentation is still pending.

In the further course of the 1970s and in the following decades, the excavation activities in Neuss never came to a complete standstill. They continue to this day, often due to emergency or rescue excavations that have become necessary as a result of construction work.

Military camp

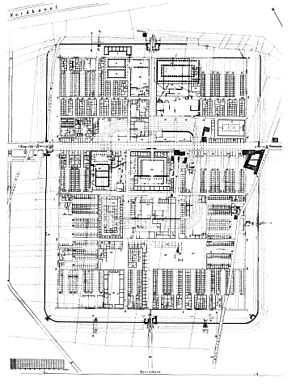

(Clemens-Sels-Museum, Neuss)

Oldest finds

Augustan-Tiberian camps A – F

The early military camps of Neuss were all located to the west of the Meertal and immediately south of today's northern canal , in the area where the feeder of today's A 57 motorway joins the canal. The twelve construction phases of these six warehouses have an average useful life of five years.

Earliest tracks

It was not until 2011 that a smaller warehouse with wooden palisades was discovered, which one year later dates back to 30/29 BC. BC could be dated.

Camp A

The so-called Camp A is considered the oldest garrison site in Novaesium. It was probably built between 20 and 15 BC. And that is to be regarded as the oldest proven Roman military camp on the Rhine border. Its Praetorial Front was oriented towards the course of the Rhine in Roman times. With its estimated (the exact size can no longer be determined archaeologically) area of 13-14 hectares, it is too small for a legionary camp. It will probably have served as a location for a larger, possibly special-purpose vexillatio . However, no name of a unit stationed here is recorded in writing. The trench was interrupted in front of the south gate. The camp had either a polygonal or a trapezoidal floor plan, was surrounded by two pointed ditches, a total of 14 meters wide, 2.5–2.8 meters deep, facing the Rhine and presumably reinforced with an earth wall or a wood-earth wall. It was of a relatively provisional character - the teams were housed in tents - and was probably built around the year 10 BC. Abandoned again.

Double legion camp B

At the same point as camp A, including this because of its significantly larger size, a large, polygonal camp was built during the Germanic offensives of Drusus and Tiberius (12–9 BC), with its measured maximum axes of 660 × 800 meters covered an area of around 45 hectares. So it should have offered space for two legions and their auxiliaries. Like camp A, legion camp B was also of a rather provisional character. It was surrounded by a 14 m wide double moat. Initially, this trench system consisted of an outer, 3.20 meter deep bottom trench and an inner, up to 1.80 meter deep pointed trench. Later a pointed ditch took the place of the sole ditch. The fence consisted of a wood-earth wall or an earth wall, the soldiers were housed in tents. The camp was abandoned at the latest in AD 14. The occupation is assumed to be the Legio XIX and either the Legio XVII or the Legio XVIII .

Four Legion Camp C

Camp C, the enclosure of which has so far only been archaeologically investigated in a few places, is estimated to have a total size of over 80 hectares. It was surrounded by a six-meter-wide pointed ditch and a wood-earth wall. Of the central buildings, the principia (staff building) with the camp forum and the praetorium (commandant's residence) are known. The building complex of the Principia resp. With its sides of 75 × 80 meters, the forum covered an area of 6000 m², of which the inner courtyard, which was surrounded by arcades and closed on three sides, accounted for 2500 m² (44 × 57 m). The Praetorium , the commandant's residential building, covered an area of over 13,000 m² with dimensions of 108 × 122 meters. It was designed in the style of a peristyle villa , with courtyards and porticos and consisted of four different parts of the building.

Camp C is regarded as the summer camp in finibus Ubiorum ("in the area of the Ubier") of the year 14 AD, which Tacitus reported in the annals . Accordingly, the Legio I Germanica (from Cologne), the Legio V Alaudae (from Vetera / Xanten), the Legio XX Valeria Victrix (from Cologne) and the Legio XXI Rapax (from Xanten) would have been temporarily brought together in Neuss. The mutiny, in the course of which the legions wanted to proclaim Germanicus emperor, would have taken place on Neuss soil.

Auxiliary camp D

Camp D, the dimensions of which could not be precisely determined but were largely estimated, covered an area of 2.5-3.5 hectares with its sides, probably 180-200 meters long and 140-180 meters wide. It was surrounded by two pointed trenches with a depth of 1.4 and 2.3 meters and a total width of almost eleven meters, and reinforced with a three-meter thick wood-earth wall. The recessed cheeks of gate structures were located at the rounded corners of the fence. The size of the camp speaks in favor of accommodating an aid group the strength of a cohors quingenaria (infantry unit with around 500 men) or cohors milliaria (infantry unit with around 1000 men) or an ala quingenaria (cavalry unit with around 500 men). The date is not clear, the military camp can only roughly be assigned to the reign of Tiberius.

Camp E.

The polygonal camp E, provided with at least six corners, had an estimated area of more than 40 hectares. It was surrounded by a five-meter-wide pointed ditch and reinforced with a simple wood-earth wall. Part of the camp was a 53 × 58 meter farm building with a 22 × 32 meter inner courtyard, which is interpreted as horreum (warehouse, granary) or fabrica (workshop). The camp was established in the early Iberian period, was probably only used for a short time and was probably given up in 17 AD - in connection with the end of the offensive policy against the Teutons.

Legion camp F

With the change in the Roman Germania policy, the troops stationed in Lower Germany were redeployed . The previously existing double legion camp at apud Aram Ubiorum (near Cologne) was dissolved. While the Legio I Germanica previously stationed there was relocated to Bonna , the Legio XX Valeria Victrix moved into quarters in Novaesium and built the so-called Camp F there. The Cohors III Lusitanorum ("3rd Lusitanierkohort ", an infantry unit from Spain) are additional auxiliary troops ) and the Ala Parthorum Veterana (" Ala Parthian Veterans", a cavalry unit from Persia). The camp underwent five to six renovation phases in which the storage area was between 22 and 26 hectares. It was surrounded by a pointed ditch up to six meters wide and reinforced with a wood-earth wall between 2.5 and 3 meters wide, which was provided with watchtowers at intervals of about 80 m. The camp existed until the legio XX Valeria Victrix was transferred to Britain in 43 AD.

Legion camp G ("Koenen camp")

Presumably due to the progressive erosion of the lower terrace and the associated gradual relocation of the Rhine arc, Legion Camp G was not built by Legio XVI Gallica on the site of older Camp F, but to the east of it in the Erft estuary.

Bearing G1

A first construction phase (camp G1) consisted of a wood-earth construction built in AD 43. It had a strictly rectangular floor plan and was initially around 420 × 570 meters in size. The fence was reinforced with towers at the rounded corners, and 60 to 120 (!) Intermediate towers, each four meters wide, are assumed. Of the gates, only the Porta Praetoria , the main gate, could be archaeologically recorded. It belonged to the type of L-shaped or hook-shaped gate systems and had a total width of 26 meters with a clear width of the doorway of 8.8 meters. The two flanking gate towers each had a width of 8.6 meters and a depth of 4.2 meters. They were connected by a 4.2-meter-wide battlements that led around a courtyard that was drawn into the interior. In front of the fence, a 3.8 m wide berm was followed by a five meter wide and almost two meter deep pointed ditch. Of the inner buildings, most of which were constructed as post structures with mortised sill beams, a corridor-type warehouse building in particular was better known, covering an area of more than 1,100 m². It consisted of the actual magazine section, which contained four rows of smaller (1.5 / 2.0 × 1.8 / 2.8 meters) chambers (79 pieces in total) separated by corridors, and an administrative complex separated from the magazine area by a passage .

Bearing G2

Camp G1 was replaced by another wood-earth camp (camp G2) around the middle of the first century AD. The renovation seems to have taken place gradually, in some smaller steps, which were more like repair measures, than in a single larger and planned renovation. The original camp defense remained, while the simple pointed ditch was replaced by a double ditch, which was attached directly to the defensive without a berm, which did not rule out a certain risk of undercutting. With a total width of the new double trench system of eight meters, the inner trench was 1.7 meters and the outer 2.3 meters deep. The assumption that the previously wooden gate systems had already been replaced by stone gates in this construction phase is not entirely certain, as the foundations had already been completely broken off at the time they were uncovered. The new system of the Porta Praetoria was 26.5 meters wide and reached a depth of approximately 15 meters. Its two gate towers were nine meters wide and enclosed a retracted gate courtyard of 7.5 × 7.0 meters. The massive construction of the building and the discovery of cornice blocks in front of the outer facade suggest that the camp on the Rhine side has an extremely representative appearance. The gate system of the Porta Decumana (rear gate) was, with a size ratio of almost 25 meters to over ten meters, slightly smaller and of less quality. Camp G2 was destroyed during the Batavian uprising in 69/70 AD.

Bearing G3

As early as 70 AD the fort was rebuilt in the same place by the legio VI victrix (camp G3), this time in stone. The defensive wall rested on foundations 1.2–1.5 meters wide and was clad on the outside with 60 × 35 cm × 30-60 cm large tuff blocks. Their height should have reached 4.0–4.5 meters on the rise. In front of the wall, following a berm more than two meters wide, ran a mighty moat in the form of a Fossa Punica . At 12.0-13.0 meters wide, the trench reached a depth of 3.5 meters below the top of the ancient terrain. The earth material obtained during the excavation of the trench (estimated 45,000 m³) was used to fill the earth wall behind the defensive wall. Only small traces of the gate systems could be found, most clearly from the Porta Praetoria . Its construction had a total width of 29.4 meters and was flanked by towers with a presumably octagonal floor plan and a diameter of six meters. In the area of the around 15 meters wide and twelve meters deep forecourt, the wall arched inwards and gave the forecourt an almost semicircular shape. The gate passage in the middle of the arch had a clear width of seven meters. The corner and intermediate towers did not have a uniform floor plan, which can possibly be attributed to subsequent repair and reconstruction measures. A Classis Germanica brick is said to have been recovered from one of these towers (or from the warehouse's drainage system) . The fence around the G3 facility was completely renewed again in the 1980s. There are different opinions in the literature about the end of legionary camp G, both the mid-90s and the years around 103/104 are assumed. It seems certain that the troop size was reduced from legionary to auxiliary strength before the final abandonment.

Infrastructure and logistics of warehouses G1 to G3

Two main traffic axes formed the road structure of the camp. The Via Praetoria led in the Praetentura (front part of the camp) from the Porta Praetoria (main gate) to the Principia (staff building) and then found in the Retentura (rear part of the camp) between the Praetorium (commandant's residence) and the Porta Decumana (rear gate) with the Its continuation via Decumana . This axis was crossed in front of the Principia by the Via Principalis , which connected the left side gate ( Porta Principalis Sinistra ) with the right ( Porta Principalis Dextra ). Another main street was the Via Sagularis , which ran around the entire camp at the foot of the defensive wall . Smaller warehouse aisles ran between these main axes. The roads were paved with crushed stone and broken stone as well as gravel and compacted layers of sand; the thickness of a single road body could easily be up to 0.35 meters. Rainwater was channeled through simple street ditches into wooden canals and from these finally disposed of in the direction of the Rhine via a stone collecting canal that crossed under the northern corner of the camp.

The Roman army tried to satisfy a large part of the material needs of the troops through self-sufficiency. For this, among other things, sufficient storage was necessary, the need for grain for a legion alone amounted to around 2000 tons per year. In Neuss - in addition to a corridor-type storage building (already described above) from construction phase G1 - five other storage buildings near Porta Praetoria were uncovered, two pillar structures and three storage buildings of the so-called “courtyard type”. The pillars were 33 meters long and 14 meters wide. Their floating floors rested on stone and brick pillars. The rising walls were provided with ventilation slots up to the level of the floating floors. There were buttresses on the outer walls to compensate for the pressure of the embedded mass. The buildings of the “courtyard type”, in which the four ten-meter-wide building wings intended for the storage of goods, enclosed an inner courtyard, had similar security and stabilization features in their construction.

Principia of camps G1 to G3

The center of all camps was ruled by the principia , the staff building of the fort. The Principia of the Koenenlager measured 70 × 73 meters in the G1 period and in their last expansion phase reached an area of 81 × 88 meters, which corresponded to a total area of over 7,100 m². One entered the building through a 6 meter wide and 12 meter long entrance hall and came into an inner courtyard lined with arcades, 46.5 meters wide and 48.0 meters long (= 2232 m²). On the long sides of the courtyard were the lines of a total of 20 rooms, which served as armories ( Armamentaria ) and writing rooms ( Tabularia ). The width of the individual rooms fluctuated - with a constant depth of seven meters - between three and seven meters. At the rear of the courtyard, a 9.6-meter-deep suite closed off the building complex. The escape contained a total of nine rooms, the middle, eight meters wide room of which was the flag sanctuary ( Aedes ). The other rooms are likely to have served as scholae (colleges) and administrative rooms . The Principia were rebuilt for the first time, probably in the G2 construction phase. The rear part of the inner courtyard was shortened by 16 m in order to gain space for a transverse hall, which was designed in the form of a three-aisled basilica, the central nave of which was ten meters wide. At the latest after the end of the Batavian uprising, with the beginning of phase G3, further renovation measures were carried out. An administration wing with a total of 14 rooms was added to the front and the two side wings of the building were widened by seven meters. The transverse hall was completely torn down and replaced with a new building.

Praetorium and tribune buildings of camps G1 to G3

In the Retentura (rear part of the camp), immediately behind the Principia , was the Praetorium , the living and presentation building of the legionary legate . It was generously and luxuriously designed on the model of a palace-like, Italian peristyle villa and, with its dimensions of 80 × 84 meters, took up an area of 6,720 m². In the south-west corner of the building complex there was presumably a thermal bath , in the north-eastern part of the palace office space was built in a later construction phase.

The accommodations of the six military tribunes were along Via Principalis , the main road of the camp, which connected the left ( Porta Principalis Sinistra ) and right ( Porta Principalis Dextra ) side gates of the camp. They were modeled on urban Mediterranean atrium houses and, with their dimensions of 38 × 38 meters, covered an area of around 1,400 m² each. Such a property was entered via a three-meter-wide vestibule (entrance hall), which led to a 100 m² inner courtyard that housed an impluvium . Four wings of the building with the living and business rooms are grouped around the courtyard. Heatable living rooms and bathrooms were standard in these luxurious buildings.

Crew quarters in camps G1 to G3

The average barracks of a centurion were about 75 meters long. Of this, the front building accounted for 24 meters with a width of eleven to twelve meters and the actual crew barracks for 51 meters with a width of seven to eight meters. The latter was divided into eleven to twelve contubernia , which consisted of an anteroom and a bedroom. Eight men shared such a contubernium , so that each soldier had a total area of just over four square meters for living and sleeping (about half of each). The head building, on the other hand, with its almost 300 m², was exclusively available to the centurion and his staff. Accordingly, the floor plans of the head buildings were designed like smaller urban atrium houses, in which the living and utility rooms were arranged around a small inner courtyard. Two such barracks buildings opened against each other and thus formed a small barracks courtyard. The pack animals may have been stored under the post-supported canopies protruding from the crew wing.

Auxiliary camp H

The so-called auxiliary camp H is located directly east-southeast of the legion camp, between these and the mouth of the Erft. It was built around the middle of the 2nd century AD by an auxiliary unit , most likely an Ala . The name of the Ala is not certain, but in the literature there is the assumption that it could have been the Ala Afrorum veterana , a pure cavalry unit of almost 500 men.

With its sides of 178 × 165 meters, the warehouse covered an almost square area of almost three hectares. It was reinforced with a stone wall reinforced with buttresses and surrounded by a double pointed ditch system, 21 meters wide. Hardly anything is known about the interior development as a result of severe and extensive post-Roman disturbances.

The end of the period of occupation of the fort is also not guaranteed. It was either destroyed at the first incursions of the Franks around 256/57 or at the latest during the massive Franconian offensive around 275/76. However, individual finds from the area of the camp and its vicus also suggest a Roman presence up to the first half of the 4th century.

Small fort, watchtower, settlement and burial ground on the Reckberg

About three kilometers east of the legionary and auxiliary camps of Novaesium were two Roman buildings, probably belonging to the same period, on two sand dunes called "First" and "Second Reckberg" on the edge of the lower terrace. From these dunes, which lay between the river and the Limes road running from Novaesium to Durnomagus, a wide view over the Rhine valley and the neighboring garrisons was guaranteed. In today's settlement geography, the two soil monuments are located in a small wooded area in the middle of agricultural areas between the Neuss districts of Grimlinghausen and Uedesheim , immediately north of the “Am Reckberg” road.

The small fort was on the "Second Reckberg" and had two construction periods. The younger stone fort had an almost square floor plan with its side dimensions of 33.0 × 34.5 meters. The defensive wall was 1.9 meters thick. Their corners were rounded, on their insides were the drawn-in cheeks of the 5.4 meter deep towers. With its single gate, a simple construction with also recessed cheeks and a passage width of three meters, the fortification was oriented towards SSW, towards Römerstraße. In front of the defense there was a double pointed ditch 6.5 m wide, which at the time of its excavation reached a depth of 4.25 meters below the top of the ground. Another double pointed ditch with a total width of seven meters, which was discovered a little outside the complex, probably belonged to an older fort built using a wood-earth construction method. The small fort on Reckberg was built at the beginning of the second century / end of the first century and was possibly used until the middle of the third century.

About 200 meters north-west of the small fort, on the "Ersten Reckberg", a square wall section measuring around 5 × 5 meters was uncovered, which was one of the foundations of a Roman watchtower. The sandstone foundations were one meter thick. The half-timbered tower rose on them. There is no information about the age of the watchtower; it was probably built at the same time as the small fort. In 1991, a reconstruction of the tower was built not far from the place where the Roman watchtower had originally stood.

About one hundred meters west of the fort, south of Römerstrasse (today's street "Am Reckberg"), the ruins of a settlement a good fifty meters in diameter were located, the burial ground of which was another fifty meters away, on the eastern slope of the "First Reckberg". Only the finds from the burial ground could be used to date the settlement, since finds from the settlement strip could have reached there immediately next to the heavily frequented Limes Road even after the settlement was abandoned. The cemetery was evidenced by the finds from the end of the first to the first half of the third century.

Late antique fortifications

The written records of Novaesium increasingly thin out over time. For late antiquity, we are therefore increasingly dependent on archaeological findings. In and around Neuss the following places can be found for the fourth century:

"Novaesium" and "Nivisium castellum"

The late antique Neuss as a military base is passed down to us in its existence through written sources as “Novesium” and “Nivisium castellum”, but it has not yet been localized. Two possible locations are controversially discussed: while some suspect the garrison in the area of the Erft estuary, others are looking for it in the area of Neuss old town. The last hypothesis is supported by the findings of two wells that were filled with finds from the period between the first and the middle of the fourth century, as well as a soldier's grave from the years between 350 and 360.

Fortification in the "Hummelbachaue"

In 1993/1994, a remarkable late Roman relic with a clearly military character was uncovered in the "Hummelbachaue" on the site of a golf course about two kilometers south-southwest of the mouth of the Erft. It was probably a one-hectare warehouse, the interior of which probably consisted of half-timbered buildings with stone foundations. The task of the troops stationed there, probably a unit of the Comitatenses , of the Roman field or movement army of this time (in contrast to the Limitanei , who were responsible for border service), was probably to secure an important road leading from the Rhine into the Limes hinterland. According to the finds, the fort was built in the late fourth century, probably as a reaction to an invasion of the Franks in 387/388, and was used until the sixth (!) Century. This makes it one of the rare examples of continuity of use from the Roman to the Frankish times.

Burgus at "Gut Gnadental"

At the end of the 1990s, a Burgus from the early fourth century was finally discovered at Gut Gnadental, a good one and a half kilometers as the crow flies southwest of the mouth of the Erft . The fortification, from which the foundations of two wall sections and a round tower could be exposed, was probably built in connection with the Constantinian restoration of the border security systems of the province of Germania secunda . The garrison's task was probably to monitor a Roman highway leading to Massilia .

troops

Legions

- Legio I Germanica

The Legio I Germanica had their headquarters in the Apud Aram Ubiorum legionary camp . Their existence is secured there for the first time in the year 14, there and as one of the four legions that were brought together in finibus Ubiorum (a place that is usually equated with "Camp C" of Novaesium ) in the summer camp and the mutiny that followed pursued the death of Augustus. This was her only stay in Novaesium . After the events of summer 14, she probably returned to Cologne, where she remained until she was moved to Bonn in 35.

- Legio V Alaudae

The Legio V Alaudae was another legion of "Camp C" that took part in the mutiny of 14. After their participation in the Gallic War and the Civil War, as well as being stationed on the Iberian Peninsula, the headquarters of the originally built around 52 BC. Chr. Excavated, Caesar's troops at this time in Vetera , where even after the short stay in Novaesium remained until their participation in the events of the 69th

- Legio VI Victrix

The year 41 BC Legio VI Victrix , founded by Octavian in the 4th century BC, had fought in the civil war and was then stationed in the Hispania Tarraconensis for almost a hundred years, where it participated in the war against the Cantabrians . In the winter of 69/70 it was relocated from Vespasian to Lower Germany, where it inflicted a decisive defeat on the Batavern rebels under the command of Petillius Cerialis in the "Battle of Vetera". She then moved into quarters in Novaesium, where she rebuilt the destroyed "Camp G" of the Legio XVI Gallica . In addition, she was involved in the restoration of numerous auxiliary camps downstream of the Rhine. In the years 78/79 she led a campaign against the Brukterer on the right bank of the Rhine . During the Saturnine Uprising , the Legion, like all units of the Lower Germanic Army, remained on the side of Domitian , which is why it received the honorary title pia fidelis Domitiana . In 104 at the latest it was relocated from Novaesium to Vetera , where it was involved in the construction of the Colonia Ulpia Traiana in accordance with its reputation as a “building region” .

- Legio XVI Gallica

In 43 the Legio XX Valeria Victrix assigned to the British campaign was replaced by the Legio XVI Gallica , which moved into "Camp G". It was stationed in Mogontiacum before (at least since 9 AD) and could have been in use in Raetia even earlier . After it had failed during the Batavian uprising and surrendered in 70, it was dissolved by Vespasian, re-established as Legio XVI Flavia company and assigned to the east of the empire.

- Legiones XVII, XVIII and XIX

The two legions that occupied "Camp B" are not secured. Basically, the Legio XVII or the Legiones XVIII and XIX, which perished in the “Battle of the Teutoburg Forest”, would be considered. Most likely the presence of the XIX. Legion.

- Legio XX Valeria Victrix

The presumably Octavian Legio XX Valeria Victrix came from the Danube region to the Rhineland, where after an initial, short stay in "Camp C" of Novaesium, it was initially stationed at Apud Aram Ubiorum . When the Cologne double legion camp was dissolved around the year 35 AD, the XX. Legion in the Neuss quarter and set up the "Camp F" there. She stayed in Novaesium for less than a decade . In 43 AD she was subordinated to the Aulus Plautius expeditionary force for the conquest of Britain. She then stayed on the British Isles

- Legio XXI Rapax

The Legio XXI Rapax was also a unit that was connected to Novaesium only through the events of the year 14. Originally around the year 31 BC. The Legion set up in the civil war had fought in Spain and Raetia before it was relocated to Vetera as a replacement and reinforcement after the Clades Variana . After her short stay in “Camp C” in Neuss, she took part in the Germanicus offensive from Vetera . Following the conquest of Britain , it was relocated to Vindonissa as part of an army regrouping .

Auxiliary troops

The size of the legionary camps of Novaesium made it necessary to accommodate the legions with their auxiliaries in one camp. However, the names of most of the auxiliaries are unknown. The following auxiliary groups can be accepted with some probability:

- Ala Afrorum veterana (?)

The Ala Afrorum Veterana is the least secure of all the auxiliary units associated with Neuss. Their stone monuments spread throughout the Rhineland and it is therefore quite conceivable the Signifer Oclatius that only random and / or temporarily in Novaesium had stopped when death overtook him, and that his real location in Burginatium , Gelduba or Vetera was . If the Novesium was actually the base of this Ala, the "camp H" should have served to accommodate them.

- Ala Gallorum Picentiana

The Ala Gallorum Picentiana , originally set up by Augustus with Gallic cavalrymen, bore the cognomen of its first commander, who was probably called Lucius Rustius Picens . It was probably relocated to the Rhine to make up for the troop losses that had arisen from the formation of the expeditionary corps to conquer Britain under Claudius. In Neuss she was stationed together with the Legio XVI in "Camp G". After the Batavian uprising, it was moved to Upper Germany.

- Ala Parthorum veterana

The Ala Parthorum Veterana, which was not entirely secured for Neuss, was an auxiliary group of mounted archers that had originally been formed from Parthian refugees. She probably came to the Rhine as a result of the Clades Variana and was stationed with the Legio XX Valeria Victrix and the Cohors III Lusitanorum in "Camp F". The assumption of their presence in Neuss is based on the discovery of a silver ring whose inscription names the Decurio der Ala , Publius Vibius Rufus . Before the middle of the first century it was moved to Upper Germany.

- Cohors III Lusitanorum

The Cohors III Lusitanorum was recruited by Augustus in north-west Spain / Portugal and probably relocated to the Rhine at the beginning of the Drusus offensive. In Neuss she was probably housed in "Camp F" together with the Tiberian Legio XX Valeria Victrix and the Ala Parthorum Veterana .

Civil settlements

Canabae legionis

As with almost all Roman military posts that were not only temporarily occupied, the Canabae legionis soon formed around the Neuss garrisons , camp suburbs in which relatives of the soldiers as well as traders, craftsmen, taverns ( canabae = pub ), brothel operators and others gather Service providers settled. Their accommodation, which initially consisted of tents and simple crates, was soon replaced by permanent structures. These buildings, mostly elongated, so-called strip houses with their gables facing the street, were lined up along the streets leading out of the fort. Workshops and shops were located in the front parts of the building facing the street, living and utility rooms and stables were located in the rear areas.

In the first three decades of the first century AD, the canabae formed on two sides of the camps: one with a length of 400 m to 750 m in an east-southeast direction along today's “Kölner Straße” and one with an area of 100 m by 300 m south-southwest of the camp, immediately east of today's A 57 / B 1 . From the fourth decade onwards, the Canabae also expanded in a west-north-westerly direction, towards the "Meertal", thus surrounding the camps on all three sides not facing the Rhine and including their necropolises almost the entire area that is today comprised of the North Canal, Sporthafen Erft and Autobahn is outlined. A Roman bridge over the Erft leading from the settlement to the southeast was not destroyed until 1586, during the war in Cologne (1583–1588).

The thermal complex of the Canabae Legionis was cut between the north canal and the hotel "Marienhof". It probably extended over an area of 30 m by 68 m, i.e. over 2000 m², and was possibly provided with apses, half of which could be exposed with a base length of ten meters and a depth of four meters. By 100 m and equipped with water tanks and apses could be addressed as a second thermal baths, but also another major building between military camp and Erft, intersected by the "Kölner Straße" m with a floor plan of over 100 Mansio , government hostel Novaesiums have been .

Civil vicus

In addition to the Canabae Legionis , all of the Rhenish legionary camps ( Noviomagus , Vetera , Novaesium , Bonna ) created civil, small-town-structured settlements along the Limes road, the so-called Vici . The vicus of Novaesium was about 1.5 km to 3 km northwest of the military installations. Its exact extent has not yet been finally clarified, based on the current townscape it probably extended from the Obertor to the Quirinus-Münster and from the Obererft to Michaelisstraße / Mühlenstraße, which is a longitudinal extension of a little over 500 m and a width between 150 m and would correspond to 250 m. Its main street corresponded to the course of today's Oberstraße, from it the side streets branched off at right angles. The floor plans of the buildings did not correspond to the strip houses of the typical Canabae or Lagervici, but rather resembled urban peristyle houses .

According to the finds, in particular through the fragments of Arretian terra sigillata , the founding of the vicus can be dated to the Tiberian period and must have been around the year 25 AD at the latest. In its first settlement phase it consisted of half-timbered buildings. The settlement was destroyed during the Batavian uprising. During the reconstruction, the half-timbered buildings were erected on stone foundations, and isolated, entirely stone buildings do not seem to be excluded. Some hypocaust systems have been found that could be used to heat at least individual living spaces. However, there is no clear evidence of temperature-controlled bathrooms. There are no traces of late Roman construction, but Roman body graves from the third and fourth centuries suggest that the settlement continued to exist in late antiquity.

Villae Rusticae

The rural inland colonization of the hinterland of Novaesium began in the second half of the first century and intensified in the second century. In addition to the agricultural use of the area, the exploitation of raw materials and the production of building materials were of certain importance. The settlement image was characterized by Villae Rusticae , isolated farms whose useful land ranged from 60 ha to 100 ha. The actual courtyard area was enclosed by a wall, fence, ditch or hedge and was divided into a pars domestica (living area) and a pars rustica (economic area). The mostly spacious and representative mansion was often equipped with a hypocaust system and a private bathroom and designed as a risalit or portico villa . The residential buildings of the staff, the stables, workshops, storehouses, barns and sheds were connected to this area. The entire residential and economic district of an estate of this size could cover up to one hectare and provide work and living space for up to 50 people. The economic activities of a Villa Rustica were not limited to agricultural production, but could also include the production of ceramics, bricks, glass and textile products or the exploitation of rock deposits.

Archaeological excavations have only been carried out on two of the numerous Villae Rusticae in the area around Novaesium . One was on the edge of the sea valley, about 450 m away southwest of auxiliary camp H. The residential building of this estate consisted of a 26 m wide and 8.5 m deep risalit villa with four meters wide and five meters deep corner projections. At the front, the building was closed off by a three-meter-deep columned hall, the dominant part of the building was a 14-meter-long central hall. The rise above the stone foundations consisted of half-timbering and wooden columns. The dating is not entirely certain. Since the building was located above a Claudian pottery workshop, a late Claudian construction can be assumed at the earliest. Modification phases were not determined. The villa was abandoned around the middle of the third century.

A second Villa Rustica could be located through a 100 m by 60 m field of Roman rubble in the “Im Hahnen” corridor in the Weckhoven district . In 1955, the remains of the foundations and excavation pits of the manor house of a Roman manor, which had been rebuilt several times, were uncovered. The homestead existed from the second half of the first to the second half of the third century. In its first construction phase, the main building of the property had a length of 32 m and a width of 17 m and was dominated by an 18 m long central hall. It was a risalit building with eight meters wide and five meters deep corner projections. At least individual rooms in the building could be heated using a hypocaust system. The stone building had replaced a previous wooden building, the post pits of which could still be identified. A Constantinian hoard was recovered around 150 m north-west of the house, but its affiliation to the villa is not certain due to the different time periods.

Burial grounds

According to the provision of the Twelve Tables Act , not only in Rome, but in all settlements of the Roman Empire up to the Villae Rusticae, the burials were never located within the settlement limits, but in some extensive cemetery fields along the arterial roads outside the populated areas. The necropolises of the various camps can also be found in Novaesium on the main connecting roads outside the camps and their associated Canabae legionis, respectively. Vici .

The extent of the burial grounds of the Augustan period has not yet been adequately clarified, but they are likely to have been along today's “Kölner Strasse”, northwest and southeast of the northern arterial road from the camps at that time. The burials of the Tiberian camps were to the right and left of the streets that branched off behind the Porta Principalis Dextra (right side gate) of the camps and ran from there in a south, south-east and east direction. In the Claudian-Neronian and Flavian times, these grave fields continued to be used, and new areas were opened up along older streets in the southwest of the camps. Since the middle of the second century at the latest, burials have also been carried out in the area of the abandoned legion camp north and south of "Kölner Straße".

The Tiberian necropolises of the civilian settlement Novaesium , located about 2.4 km northwest of the Koenen camp, could not yet be located; they are assumed to be in the direction of Reuschenberg . The main burial ground of the settlement was in the area between the medieval Quirinus Minster and today's Neuss central station. In addition, burials from the second half of the first century were uncovered south of the settlement.

The forms of burial changed over time. In the first century, cremations dominated, the central cremation sites of which , the so-called Ustrinae , were in every cemetery. From the Ustrina, the corpses were buried in an urn or stone box, or in the form of a fire pit or a fire grave. In addition, since the second half of the first century there was the special burial form of bustum , in which the body was burned on a pyre directly above the open grave pit. Based on the belief that the deceased had similar needs in the hereafter as during their lifetime, appropriate additions (food, drinks, dishes, household appliances, jewelry, money, etc.) were given to the grave. Also gifts that had to do with the professional activity of the deceased were quite common; However, soldiers were excluded from this custom, as their weapons were not their private property but belonged to the state. The strikingly high number of incense chalices at the Neuss burials could have been related to corresponding ceremonies during the burial.

From the first half of the third century, body burials began to appear in Neuss, which eventually became the dominant form of burial in the second half and fourth centuries. Simple linen cloths or wooden boxes, but also lead coffins and intricately designed stone sarcophagi were used to hold the corpses. The orientation of the graves in Neuss was initially carried out mainly in a north-south direction, until the east-west orientation prevailed in the fourth century, possibly influenced by Christian ideas.

Above ground, the graves were marked by tombstones, altars, pillars or temples, right through to monumental grave structures. But even simple, wooden grave markings, which are no longer archaeologically verifiable today, can and must be accepted for the poorer sections of the population. The stone tombs were provided with inscriptions that still provide us with valuable information about the name, gender, age, occupation or military rank of the deceased.

Green glazed beaker, glazed earthenware with barbotine style , 1st century

(Clemens-Sels-Museum, Neuss)

Fossa sanguinis

A unique finding of its kind for the Germanic provinces is a “cult cellar”, a so-called “blood ditch” ( Fossa Sanguinis ) . The building complex was uncovered in 1956/57 during rescue excavations by the Rheinisches Landesmuseum Bonn. The cult district is located in the Gnadental district of Neuss in the area of today's Gepa-Platz. In ancient times it was located in a temple district on the south-western edge of the auxiliary vicus. According to the finds, it probably only existed for a short time in the first half of the fourth century and was abandoned and filled in around the year 340. The facility is an almost square cellar with a side length of around 1.80 m and a remaining depth of 1.40 meters. The walls and two opposite stairs leading to the basement are made of greywacke, tuff and limestone, some of which are used as secondary stones. The floor was made of rammed earth covered with planks. Above the basement there was presumably the ceiling consisting of a beam construction, which was supported by an additional wooden construction anchored to the basement stairs, despite the small dimensions and the therefore quite small loadable area of only around 3.25 square meters.

This circumstance, which suggests an above-average load on the cellar ceiling, as well as the composition of the finds, led the excavation manager Harald von Petrikovits to interpret this finding as fossa sanguinis , a baptismal font of the cult of Cybele or its Roman equivalent, the Magna Mater . In their mystery rituals, which have been handed down by the late antique writer Prudentius , the person to be baptized was baptized with blood. He went into a cellar or a covered pit where a bull or ram was slaughtered . The blood ran through the ceiling over the crouching baptized person , who only after this ritual, understood as cleansing and regenerating for eternity (renatus in aeternum) , finally belonged to the community.

Both the tradition of Prudentius and the interpretation of the findings by von Petrikovitz are sometimes viewed critically in the literature, but have not necessarily been refuted to this day. The fossa sanguinis has been preserved, given a protective structure and can be viewed.

- Finds from the Sanguinis fossa

Monument protection and museum presentation

Monument protection

The forts of Novaesium are ground monuments according to the law for the protection and care of monuments in the state of North Rhine-Westphalia (Monument Protection Act - DSchG) . Research and targeted collection of finds are subject to approval. Incidental finds are to be reported to the monument authorities.

Historical tour

For the so-called 2000 year celebration of the city of Neuss, a “historical tour” was laid out through the former Roman garrison area. The tour points to sites where the Roman camp was found and shows some exhibits, not all of which come from Neuss:

- Jupiter column

A column (from Erkelenz-Klein Bouslar) rises above the base of a four-god stone with the representations of Hercules , Ceres , Mercury and Vulcanus (found in Cologne-Weiden) with the images of Juno , Minerva and Mercury, those of an enthroned Jupiter (from Bonn) is crowned. The three components all come from the 3rd century, the original is in the Rheinisches Landesmuseum Bonn.

- Gravestone of Oclatius

Oclatius served as signifer (standard bearer) in the Ala Afrorum , a cavalry unit originally raised in Africa, which was probably stationed in Neuss in the 1970s. Oclatius, who is shown in the upper relief with the standard of his unit, was a Tungrian , so he came from the area around today's Tongeren in Belgium. On the lower relief, a groom leads the signer's saddled horse. He must have a bundle of lances on his shoulder. The tombstone was discovered in 1922 on Kölner Strasse. The inscription between the two reliefs reads:

- Oclatio Carvi f (ilio)

- signif (ero) alae Afror (um)

- Tungro frater h (eres) f (aciendum) c (uravit)

- Translation: "For Oclatius, son of Carvus, standard bearer of the Ala Afrorum, from the tribe of the Tungrer, the brother and heir had (this tombstone) made."

- Gravestone of Pancuius

The grave stele of Tiberius Iulius Pancuius was found on Kölner Strasse in 1950. Pancuius was the signifier of an auxiliary cohort that had been set up in the province of Lusitania on the Iberian Peninsula. Presumably between AD 20 and 43, the troops were stationed in Novaesium to support the 20th Legion . The inscription below the relief portrait reads:

- Tiber (ius) Iulius

- Pancuius

- mil (es) coh (ortis)

- Lusitanorum

- an (norum) LV stip (endiorum) XXVIII

- hic s (i) t (us) est

- Translation: "Tiberius Iulius Pancuius, soldier of the Lusitanian cohort, at the age of 55, with 28 years of service, is buried here."

- Former location of the Roman bridge

Information board on the former eight-arched stone bridge over the Erft, which was blown up by Spanish troops in the 1586 War of the Truchess .

- Tufa stones from the legionary camp

Hewn stones with which the outer walls of the so-called Koenen camp were faced between 70 and 85 AD.

- Stations of the "historical tour"

Clemens Sels Museum

The origins of the archaeological collections of the city of Neuss go back to the private collections of the members of the first Neuss antiquity society. In 1845 the first municipal museum was built at Obertor for this purpose. In 1900 a large part of the inventory was lost in a fire. In 1912 the foundation of Pauline Sels, the widow of a collector, was able to move into a new building on Neusser Markt. Since then, the museum has borne the name of this collector as the Clemens Sels Museum, whose holdings have been incorporated into the house's fund. The building was almost completely destroyed in the Second World War. The museum was not reopened until 1950, again at Obertor. An additional new building was added in 1975.

The archaeological collection contains archaeological finds from all prehistoric and early historical epochs since the Paleolithic, which are represented in the Neuss city area. The Roman exhibits naturally form a focus of the collection.

- Roman exhibits in the Clemens Sels Museum

In addition to the archaeological collection, there are also the departments documents on city history, art and applied arts from the 12th to 18th centuries, art from the 19th to 21st centuries, naive art and folk art, folk art, toys.

See also

- List of troop camps on the Lower Germanic Limes

- List of the Roman vici in Lower Germany

- Kybele cult site (Neuss)

literature

- Tilmann Bechert : Roman Germania between the Rhine and Maas. The province of Germania inferior . Hirmer, Munich 1982, ISBN 3-7774-3440-X , (= Edition Antike Welt 4)

- Tilmann Bechert, Willem J. H. Willems : The Roman imperial border from the Moselle to the North Sea coast . Stuttgart 1995, ISBN 3-8062-1189-2 .

- Steve Bodecker: Koenenlager digital. Findings register for the Neuss legionary camp . In: The Limes. News bulletin of the German Limes Commission. 5th year, 2011, issue 1, pp. 4–7. ( also online ; PDF; 3.9 MB)

- Julianus Egidius Bogaers , Christoph B. Rüger (Hrsg.): The Lower Germanic Limes. Materials on its story . Rheinland Verlag, Cologne 1974, ISBN 3-7927-0194-4 .

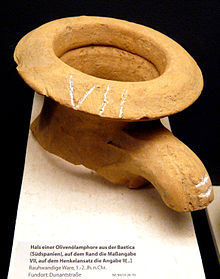

- Auguste Bruckner and Mercedes Vegas: The Augustian utility ceramics from Neuss . Gebr. Mann, Berlin 1975, ISBN 3-7861-1065-4 , (= Limes research 14, = Novaesium 6)

- Heinrich Chantraine u. a .: The Roman Neuss . Theiss, Stuttgart 1984, ISBN 3-8062-0356-3 .

- Heinrich Chantraine: The ancient coins found in the excavations in Neuss . Gebr. Mann, Berlin 1968, (= Limes Research 8, = Novaesium 3)

- Heinrich Chantraine: The ancient coins found in the excavations in Neuss. Complete catalog of the excavations 1955–1978 . Gebr. Mann, Berlin 1982, ISBN 3-7861-1232-0 , (= Limes research 20, = Novaesium 8)

- Elisabeth Ettlinger : The Italic Sigillata of Novaesium. Gebr. Mann, Berlin 1983, ISBN 3-7861-1369-6 , (= Limes research 21, = Novaesium 9)

- Philipp Filtzinger : The Roman ceramics from the military area of Novaesium. Gebr. Mann, Berlin 1972, ISBN 3-7861-1052-2 , (= Limes research 11, = Novaesium 5)

- Michael Gechter : The military history on the Lower Rhine from Caesar to Tiberius. A sketch . In: T. Grünewald, S. Seibel (Ed.): Continuity and Discontinuity. The Germania Inferior at the beginning and at the end of Roman rule, contributions to the German-Dutch colloquium at the Katholieke Universiteit Nijmegen, June 27th to 30th, 2001 . In: Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde . Supplementary volume 35, de Gruyter, Berlin 2003, pp. 147–159.

- Michael Gechter: Early Roman military installations and Ubian settlements in the Lower Rhine . In: T. Blagg, M. Millett (Eds.): The early Roman empire in the West . 2nd Edition. Oxford Books 2002, ISBN 1-84217-069-4 , pp. 97-102.

- Michael Gechter: The beginnings of the Lower Germanic Limes . In: Bonner Jahrbücher 179, 1979, Rheinland-Verlag, Bonn 1979, pp. 1–129.

- Helmut Gilliam: Romans in Neuss. 2000 years of Römer on the Rhine. Collection of materials on the history of Novaesium. Culture Office of the City of Neuss, Neuss 1983

- Norbert Hanel : On the dating of the early imperial military camps of Novaesium (Neuss) . In: Ph. Freeman et al. (Ed.): Limes XVIII. Proceedings of the XVIIIth International congress of Roman frontier studies . Amman 2000. British Archaeological Reports, International Series 1084.1. Oxbow Books, Oxford 2002, ISBN 1-84171-463-1 , pp. 497-500.

- Heinz Günter Horn : Neuss. Historical tour. In the S. (Ed.): Die Römer in Nordrhein-Westfalen licensed edition of the 1987 edition. Nikol, Hamburg 2002, ISBN 3-933203-59-7 , p. 586 ff.

- Heinz Günter Horn: Neuss. Roman cellar. In the S. (Ed.): Die Römer in Nordrhein-Westfalen Licensed edition of the 1987 edition. Nikol, Hamburg 2002, ISBN 3-933203-59-7 , p. 588 f.

- Karl-Heinz Knörzer : Roman times plant finds from Neuss. Gebr. Mann, Berlin 1970, ISBN 3-7861-1042-5 , (= Limes research 10, = Novaesium 4)

- Constantin Koenen : Description of Novaesium . In: Bonner Jahrbücher of the Verein von Altertumsfreunden im Rheinlande, Issue 111/112, Marcus & Weber, Bonn 1904, pp. 97–242.

- Constantin Koenen u. a .: Novaesium. The legionary camp excavated by the Bonn Provincial Museum 1887–1900 on behalf of the Rhenish Provincial Association . Ribbon with 36 plates. In: Bonner yearbooks of the association of friends of antiquity in the Rhineland, issue 111/112, tables. Marcus & Weber, Bonn 1904

- Jürgen Kunow : The military history of Lower Germany . In: Heinz-Günter Horn (Ed.): The Romans in North Rhine-Westphalia . Licensed edition of the 1987 edition. Nikol, Hamburg 2002, ISBN 3-933203-59-7 , pp. 27-109.

- Hans Lehner : The individual finds from Novaesium . In: Bonner yearbooks of the Association of Friends of Antiquity in the Rhineland, issue 111/112. Marcus & Weber, Bonn 1904, pp. 243-418.

- Sophia von Lith : The Roman glasses from Neuss. Complete catalog of the excavations 1955–1978 . In: Bonner Jahrbücher , Volume 194, 1994, Butzon & Bercker, Kevelaer 1995, ISSN 0938-9334 , pp. 205-340.

- Geo T. Mary: The southern Gaulish Terra sigillata from Neuss . Gebr. Mann, Berlin 1967, (= Limes Research 6, = Novaesium 1)

- Gustav Müller: Neuss. Novaesium . In: Heinz Günter Horn (Ed.): Die Römer in Nordrhein-Westfalen Licensed edition of the 1987 edition. Nikol, Hamburg 2002, ISBN 3-933203-59-7 , p. 580ff.

- Gustav Müller: The Roman burial grounds of Novaesium . Gebr. Mann, Berlin 1977, ISBN 3-7861-7000-2 , (= Limesforschungen 17, = Novaesium 7)

- Heinrich Nissen: History of Novaesium . In: Bonner yearbooks of the Association of Friends of Antiquity in the Rhineland. Issue 111/112, Marcus & Weber, Bonn 1904, pp. 1-96.

- Harald von Petrikovits : Novaesium. Roman Neuss. Böhlau, Cologne and Graz 1957

- Hans Schönberger : The Roman troop camps of the early and middle imperial period between the North Sea and Inn . In: Report of the Roman-Germanic Commission 66, 1985, Zabern, Mainz 1985, pp. 321–495.

- Hans Schönberger: The Roman Frontier in Germany. An Archaeological Survey . In: The Journal of Roman Studies , Vol. 59, No. 1/2, 1969, pp. 144-197.

- Hans Schönberger and Hans-Günther Simon : The mid-imperial terra sigillata from Neuss . Gebr. Mann, Berlin 1966, (= Limes research 7, = Novaesium 2)

- Max Tauch : Neuss. Clemens Sels Museum . In: Heinz Günter Horn (Ed.): The Romans in North Rhine-Westphalia . Licensed edition of the 1987 edition. Nikol, Hamburg 2002, ISBN 3-933203-59-7 , pp. 589-591.

- Max Tauch: Clemens Sels Museum Neuss. Roman department . Schnell and Steiner, Munich 1983

- Multimedia documentation

- Christiane Zangs: The camp of the VI. Legion. The Roman garrison of Novaesium - Neuss . CD-ROM. Theiss, Stuttgart 2003, ISBN 3-8062-1841-2 .

Web links

- Novaesium, alias Neuss - Archeology and History of Roman Neuss on the private website of the archaeologist Jürgen Franssen

- Legion camp G on Heinz Birkenheuer's private website

- Clemens-Sels-Museum , official website

- Castrum Novaesium on the official website of the city of Neuss

- Digital archeology Legion camp, end of the 1st century

- Digital archeology Porta principalis sinistra (west gate) of the legionary camp, interior view, 1st century AD

- Digital archeology north gate of the legionary camp (exterior view)

- Digital archeology Via Praetoria of the legionary camp

- Digital archeology Valetudinarium (Hospital) 1st century AD

Remarks

- ↑ a b c d e After Michael Gechter: The military history on the Lower Rhine from Caesar to Tiberius - a sketch . In: Thomas Grünewald and Sandra Seibel (eds.): Continuity and Discontinuity. The Germania Inferior at the beginning and at the end of Roman rule. Contributions to the German-Dutch colloquium at the Katholieke Universiteit Nijmegen (June 27–30, 2001) . De Gruyter, Berlin 2003, ISBN 3-11-017688-2 (= Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde, Supplementary Volume 35), the chronology of the camps should differ from the previous research as follows: A1 to 1 AD, B1 1 to 4/5 AD, A2 4/5 to 9 AD, B2 9 to 14 AD, D 14 to 16 AD, E again 24 to 43 AD as a double legion camp.

- ↑ “In the meantime the mutiny had broken out in Novaesium. The soldiers had found out that a donation intended for them by Vitellius had reached the general and forced it to be distributed in the name of Vespasians . As soon as they had it, the old soldiers' resentment broke out again in the wild feasts that followed the donation; They plundered the house of the general who had betrayed the Rhine Army to the general of the Syrian legions, killed him and would have inflicted the same fate on Vocula if he had not escaped in disguise. Then they again proclaimed Vitellius emperor, not knowing that he was already dead. When this news reached the camp, the better part of the soldiers, namely the two Upper Germanic legions, came to some senses; they exchanged the portrait of Vitellius for the Vespasians on their standards and placed themselves under Vocula's orders; this led them to Mainz, where he stayed for the rest of the winter of 69/70. Julius Civilis occupied Gelduba and thereby cut off Vetera, which was again closely blocked; the camps of Novaesium and Bonna were still held. ” Theodor Mommsen : Roman History. Eighth book. Countries and people from Caesar to Diocletian. 1887. Reprinted by Mundus, o. O. 2000, p. 92 f. See also Theodor Mommsen: The Roman Empire of the Caesars in the Gutenberg-DE project

- ↑ In this context, a letter from Antonius Primus to Civilis is often quoted, which should have reached its addressee in the late summer of 69 AD and in which the Batavians were asked to intervene in the war on Vespasian's side. (Tacitus, Histories 4, 13); Barbara Levick: Vespasian . Routledge, London 1999, ISBN 0-415-16618-7 , p. 108.