Albaniana

| Albaniana | |

|---|---|

| limes | Lower Germanic Limes |

| Dating (occupancy) | 1a) 40/41 to 56 (?) 1b) 56 (?) To 60 1c) 60 to 69/70 2) 70 to around 160 3a) around 160 to 180/190 3b) around 180/190 to around 208 / 211 3c) at 208/211 to 270/275 |

| Type | Cohort fort |

| unit | 1) unknown (Vexillatio?) 2) Cohors VI Breucorum 3) Cohors XV voluntariorum civium Romanorum (?) |

| size | 80 m × 120 m |

| Construction | 1) Wood-earth warehouse 2) Wood-earth warehouse 3) Stone fort |

| State of preservation | overbuilt |

| place | Alphen aan den Rijn |

| Geographical location | 52 ° 7 '45.9 " N , 4 ° 39' 41.8" E |

| height | 0 m NAP |

| Previous | Nigrum Pullum (southeast) |

| Subsequently | Matilo (west-northwest) |

| Upstream | Flevum (north) |

Albaniana or Albanianiae (which can be roughly translated into German as the white waters ) was the ancient name of a Roman cohort fort on the Lower Germanic Limes . The relics of the former military camp are now largely built over in the center of Alphen aan den Rijn , a town and municipality in the Dutch province of South Holland .

Location, sources and research history

The former military camp was located at the mouth of the Aar into the Oude Rijn . There are similarities to Nigrum Pullum in the choice of storage location . As with this one, the direct, but lower-lying position immediately opposite the river mouth was given preference over a location on slightly more distant, but higher-lying terrain. This raises all the more questions as both military camps were located in an area in which the tidal range of the Rhine caused by the North Sea must have been clearly noticeable.

The ancient name Albaniana is recorded both in the Tabula Peutingeriana and in the Itinerarium Antonini .

Archaeological relics from the center of Alphen have been known since the 16th century, and have repeatedly come to light, especially in the area of the church hill. But it was not until the Advent church was built (1920–1922) that more concrete traces were observed, which did not lead to any major investigations. Scientific investigations took place for the first time after the Second World War, but only to a very limited extent, because at that time the large excavations in Valkenburg pushed everything else out of the public focus in Dutch archeology . The scanty findings remained difficult to interpret, and interest flattened out. An excavation in 1959 north of the Advent Church unearthed the fort baths , but was only published in three short messages. Further excavation opportunities on major construction projects in the 1960s and 1970s were unfortunately missed. Large areas of the southern fort area known today must therefore be viewed as irretrievably destroyed. It was not until 1985/1986 that an investigation by the Katholieke Universiteit Nijmegen (today: Radboud University Nijmegen ) in the west of the Julianastraat led to further results. During these excavations, obvious traces of a crew barrack could be found. The confirmed discovery of Albanianas finally came about in 1998/1999 as part of the investigations made necessary by the planned construction of a shopping center under the direction of Jan Kees Haalebos , the professor for Provincial Roman Archeology at the Katholieke Universiteit Nijmegen . Parts of the fort, the civil settlement ( vicus ) and the burial grounds could be explored. Further investigations were carried out in 2001/2002. In this excavation campaign, the overwhelming number of around 40,000 pieces of ceramics, 800 coins, 5,000 other metal objects and hundreds of kilograms of bones, bricks and natural stone were recovered. In addition, 1,500 wood samples and 200 soil samples were taken.

Findings, finds, interpretations and history

Inside the fort, barracks with wooden floors have been identified. Many of the soldiers' personal belongings were still on site, including a mirror and writing utensils as well as hundreds of Roman coins. Furthermore, various wooden components, including a complete door, as well as organic material such as leftovers and plant seeds.

The rough periodization, which was created after the first excavations in 1998/1999, could be significantly refined after the second excavation campaign in 2001/2002. The problem was that only the traces of the first phase were well preserved, while most of the relics of the more recent phases fell victim to centuries of intensive agricultural use of the site.

Period 1a to 1c (41 to 69/70)

Albaniana is one of the few auxiliary forts whose founding date falls during the short reign of Caligula . A dendrochronological examination of the timber refers to the time immediately after Caligula's journey to the area of the later province of Germania inferior in the years 39/40. This evidence is further corroborated by the fact that 340 of 579 found coins refer to the time of this emperor.

From the coins found during the 1998 and 2001/2002 excavation campaigns, a total of 579 coins could be dated:

| Embossing | Time position | 1998 excavation | Excavation 2001/2002 | total | proportion of |

| Republican | before 27 BC Chr. | 0 | 17th | 17th | 2.94% |

| Augustan | 27 BC Chr. – 14 AD | 4th | 40 | 44 | 7.60% |

| Tiberian | AD 14–37 | 0 | 26th | 26th | 4.49% |

| Caligula | 37-41 | 16 | 324 | 340 | 58.72% |

| Claudian | 41-54 | 5 | 67 | 72 | 12.44% |

| Neronian | 54-68 | 2 | 16 | 18th | 3.11% |

| Four emperor year | 68/69 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0.35% |

| Flavian | 69-96 | 6th | 38 | 44 | 7.60% |

| Nerva | 96-98 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0.35% |

| Trajan | 98-117 | 2 | 6th | 8th | 1.38% |

| Hadrian | 117-138 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0.17% |

| Antonine | 138-161 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 0.52% |

| Marc Aurel | 161-180 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0.17% |

| Gordianus III. | 238-244 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0.17% |

| TOTAL | 1st century BC BC to 3rd century AD | 37 | 542 | 579 | 100.01% |

In 38 Caligula had moved to Mainz with a large army to pacify aggressive Germanic tribes on the other side of the Rhine. Then, in 40, he moved on to the North Sea coast to follow in Caesar's footsteps and set out on a conquest of Britain . However, the expedition was canceled. The truth of the absurd processes Suetonius describes in this context is an open question. Research had long assumed that these events took place in Boulogne-sur-Mer , but in recent years there have been increasing numbers of clues pointing to the western Netherlands. The establishment of the forts of Valkenburg ( Praetorium Agrippinae ) in 40 and of Albaniana a year later could well have been connected with a planned invasion of Britain. In January 41, Caligula was replaced by Claudius , who then actually started the conquest of Britain in 43.

Period 1a

Nothing is known about the troops stationed in Albaniana at that time . The names engraved as graffiti on Terra sigillata vessels are of Latin origin, so it is conceivable that the Vexillatio of a Legio moved into quarters here, i.e. soldiers with Roman citizenship were on site.

The traces of the first construction phase were mainly found in the southern half of the fort, in the north they had almost completely disappeared. The fort was made of wood and its praetorial front was oriented towards the east, towards the Rhine. It was surrounded by two defensive trenches and protected by a three-meter-wide wood-earth wall (with a skeleton made of soft coniferous logs ). The south gate (the Porta principalis dextra (right side gate)) and the southwest corner tower could still be verified. The corner tower and the two towers that flanked the south gate were each based on six solid wooden posts. The wood of the fence could be dendrochronologically dated to autumn / winter 40/41 and spring 41, while the material used for the interior structures came from the year 42. Probably the soldiers were initially housed in tents. Due to its close proximity to the Rhine, the floor plan of the camp had to adapt to the topographical conditions, which led to it taking the form of a parallelogram.

Inside the camp, in the right praetentura (rear half of the camp), there were traces of three wooden, north-south facing crew barracks, in the left praetentura the remains of other buildings, also made of wood, including a horreum (granary) and a fabrica (Workshop).

Periods 1b and 1c

For the following years, two repair phases could be determined on the warehouse fence: The warehouse was renewed in 56 (?) And (60) respectively. The same applies to a bank fortification that was built directly at the camp in 42. This quay was completely repaired in years 51 and 67.

Not only the Albaniana fort, but the military infrastructure of the entire Rhine line was fundamentally improved. This is also reflected in the find complexes of periods 1b and 1c. While period 1a was characterized both materially and nutritionally by the availability of the bare essentials, equipment and catering improved continuously in the following years. More luxury ceramics and glass were found, among other things, and the soil samples provided evidence of a wider and richer diet.

After Nero's death in 68, a civil war broke out over his successor, which affected large parts of the empire. One of the pretenders to the throne was Vitellius , the commander of the Lower Germanic army district. When he withdrew a large part of the troops in order to enforce his claims and thus weakened the Rhine border, the Batavians (spurred on by his rival Vespasian ) took the opportunity and revolted against the Roman occupation. The forts were conquered or evacuated and burned down by the garrison commanders. This also happened in Albaniana.

Period 2 (70 to 160)

In 69 Vespasian emerged victorious from the civil war , subjugated the rebellious Batavians in 70 and had the castles on the Rhine rebuilt. Albaniana was extended slightly to the north, but retained its trapezoidal plan. Little is known about the structure of the new camp. It was probably surrounded by three pointed trenches that were so deep that they were constantly under water. This is supported by the seeds of aquatic plants that were recovered from soil samples from the trenches. For the first time, individual buildings were covered with roof tiles, which were probably produced on site by the troops themselves. Through the brick stamp, the Cohors VI Breucorum (6th cohort ) of the Breuker was identified as the troop that was stationed in Albaniana that was probably stationed in Albaniana until around 120.

Since wood was still the most important building material, considering the ninety years of existence of the second warehouse, several renovation phases are naturally assumed, but these could not be proven. However, they are proven for the bank reinforcement, which was thoroughly renewed at least twice, according to dendrochronological dating in the years 94 and 124/125. A major reason for repair work seems to have been the erosion caused by the activities of the Rhine in the tidal area of the North Sea.

Period 3a to 3c (160 to 270/275)

Around 160 the fort was provided with a stone defensive wall and stone towers. Extensions and subsequent renovations were carried out by construction crews of the Legio I Minervia , in part using building materials produced by the Tegularia transrhenana ("brickworks on the other side of the Rhine") operated by this legion . There is uncertainty about the unit that was stationed in Albaniana in the third period. A single owner inscription from this refers to the Cohors XV voluntariorum civium Romanorum , other graffiti show names as they are known from the Danube region.

Period 3a

The plan in the form of a parallelogram was retained, but the area on the north side of the camp was initially reduced to that of the pre-Flavian period. Presumably due to the meanwhile heavy deforestation, especially south of the Rhine, which led to a reduced rainwater retention capacity in these regions, there were stronger floods, which after around 20 to 30 years led for the first time to parts of the first around 180/190 Steinkastells were washed away.

Periods 3b and 3c

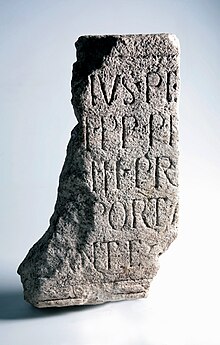

Lorraine limestone

AO: Provinciaal Archeologische Depot Zuid-Holland

At the beginning of the second century, between 208 and 211, the floods of the Rhine again destroyed parts of the fort defenses built around 180/190 (end of period 3b). At least the south wall and the Porta decumana were damaged by this flood.

The beginning of period 3c could be well dated by the building inscription in honor of the emperor Septimius Severus :

[Imp (erator) Caes (ar) L (ucius) Sept (imius) Severus P] ius Pe [rtinax Aug (ustus)] / [pont (ifex) max (imus) tr (ibunicia) pot (estate) 3] I p (ater) p (atriae) pe [r milites leg (ionis) I Min (erviae) P (iae) F (idelis)] / [Antoninianae coh (ortis)] III pr [aetoriae 3] / [3 murum cum] porta [vetust] a [te collap] / [sum a solo rest (ituit) cura] nte [Venid] io [Rufo leg (ato) Aug (usti) pr (o) pr (aetore)].

(Translated: The Emperor Caesar Lucius Septimius Severus Pius Pertinax Augustus, Pontifex Maximus , owner of tribucinic powers , father of the fatherland, (became) by the soldiers of the 1st Legion Minervia with the surname the Loyal, the loyalty of Antoninus , the third Praetorian cohort the wall with the gate, which collapsed by itself, was erected again under the care of Venidius Rufus, imperial legate with the rank of praetor . )

The camp existed in its last form until it was probably abandoned around 270/275 when Roman troops left the Rhine in this section. The finds from Badorf ceramics indicate that the ruins were finally used as a quarry from the early Middle Ages and were completely demolished by the eighth or ninth century.

State of preservation and museum presentation

The remnants of the Albaniana Fort are largely built over under the densely built-up city center of Alphen. Nothing can be seen above ground, but large areas of the fort, the vicus and the burial grounds have also been largely destroyed by structural interventions and archaeological excavations in the ground. At best, modern works of art are reminiscent of the Roman era in today's cityscape. Find material from the two Alphen garrisons Nigrum Pullum and Albaniana, as well as information about the Roman past of the city can be found today in three different places.

On the ground floor of the Archeologiehuis Zuid-Holland , the Roman history of the area around Alphen aan den Rijn and the province of South Holland is presented. The focus of the presentation is the representation of the transition from the Iron Age to the Roman Age using more than 600 exhibits.

Numerous finds from Alphen found their way to the Rijksmuseum van Oudheden in Leiden , just under 20 km away , where most of them are in the museum's magazines, but the highlights are part of the permanent exhibition.

- Military finds from Albaniana

- Civil finds from Albaniana

The privately run "Archaeological Theme Park Archeon " in Aalphen aan den Rijn is not unimportant and - because it is designed in a very popular science - very popular with the public . The ambitious project Zwammerdamschepen en Nationaal Romeins scheepvaartmuseum (ships from Zwammerdam and the National Roman Maritime Museum) is to be implemented here by 2021 . The project is related to the requested recognition of the Lower Germanic Limes as a UNESCO World Heritage Site and is intended to include all six ships of the Zwammerdam ship finds that are currently still preserved or are in restoration workshops , such as in the Nederlands Instituut voor Scheeps- en onderwater Archeologie ( NISA) in Lelystad , again at the place of their discovery and make them visible.

See also

literature

- Peter Bakker, Jan Willem Bron: Gered uit de grond. Romeinse vondsten van Castellum Albaniana. Spider Graphics, Leiden 2013, ISBN 978-94-90498-12-2 .

- Julianus Egidius Bogaers : Alphen aan den Rijn - Albaniana. In: Julianus Egidius Bogaers and Christoph B. Rüger : The Lower Germanic Limes. Materials on its story. Rheinland-Verlag, Cologne 1974, ISBN 3-7927-0194-4 , pp. 46-47.

- Julianus Egidius Bogaers, Jan Kees Haalebos : Opgravingen te Alphen aan den Rijn in 1985 and 1986. In: Westerheem 26 (1987), pp. 40-52.

- Jan Kees Haalebos, Paul Franzen et al .: Alphen aan den Rijn. Albaniana 1998-1999. Opgravingen in de Julianastraat, de Castellumstraat, op Het Eiland en onder het St.-Jorisplein. Nijmegen 2000, ( also digitized as pdf ).

- Jan Kees Haalebos: A Severan building inscription from Alphen aan den Rijn-Albaniana. Acta Archaeologica Lovaniensia, Monographiae 12 (2001), ( also digitized as pdf ), pp. 41–46.

- Wilfried AM Hessing : The Dutch coastal area. In: Tilmann Bechert and Willem J. H. Willems (eds.): The Roman border between the Moselle and the North Sea coast. Theiss, Stuttgart 1995, ISBN 3-8062-1189-2 , p. 92f.

- Fleur Kemmers : Caligula on the Lower Rhine. Coin finds from the roman fort of Albaniana (The Netherlands). Revue belge de numismatique et de sigillographie 150 (2004), pp. 15-50, ISSN 0774-5885 .

- Annemarie Luksen-IJtsma: De limesweg in West-Nederland. Inventory, analysis and synthesis of archeological onderzoek naar de Romeinse weg tussen Vechten en Katwijk. Basic report archeology 40 . Cultuurhistorie, gemeente Utrecht, Utrecht 2010, ISBN 978-90-73448-41-4 .

- Marinus Polak , René PJ Kloosterman, Ryan AJ Niemeijer: Alphen aan den Rijn. Albaniana 2001-2002. Opgravingen tussen de Castellumstraat, het Omloopkanaal en de Oude Rijn. Nijmegen 2004, ISBN 90-802647-5-X , ( also digitized as pdf ).

- Marinus Polak: Het Romeinse castellum Albaniana in het centrum van Alphen aan den Rijn. Radboud Universiteit, Nijmegen 2004.

- Marinus Polak, Ryan AJ Niemeijer, E. van der Linden: Alphen aan den Rijn-Albaniana and the dating of the Roman forts in the Rhine delta. In David Bird (ed.): Dating and interpreting the past in the western Roman Empire. Essays in honor of Brenda Dickinson. Oxbow, Oxford 2012, pp. 267-294.

Web links

- Marinus Polak : Het Romeinse castellum Albaniana in het centrum van Alphen aan den Rijn . ( Municipality of Alphen aan den Rijn - Research Summary Report on Albaniana , Word document), Gemeente Alphen aan den Rijn and Radboud Universiteit Nijmegen , 2004 or later, ( Dutch ), accessed April 30, 2018

- Alphen aan den Rijn (Centrum) - Albaniana on cultuurwijzer.nl, an official website for the cultural heritage of the Netherlands, (Dutch) , accessed on April 28, 2018

- Jona Lendering: Albaniana (Alphen aan den Rijn) . In: Livius.org (English), accessed on January 21, 2019

Individual evidence

- ↑ A Lugduno Argentorato mpm cccxxv sic Albinianis mpm x Traiecto mpm xvii ... [From Lugdunum Batavorum ( Katwijk ) to Argentorate ( Strasbourg ) 330 miles, of which from Lugdunum Batavorum to Albaniana ten miles, from Albaniana to Traiectum ( Utrecht ) 17 miles. ..]

- ↑ In: Nieuws-Bulletin van de Koninklijke Nederlandse Oudheidkundige, Volume 12 (1959), p. 59, p. 84 and p. 98f.

- ↑ Jules Bogaers, Jan Kees Haalebos: Opgravingen te Alphen aan den Rijn in 1985 and 1986. In: Westerheem 26 (1987), pp. 40-52.

- ↑ Marinus Polak, René PJ Kloosterman, Ryan AJ Niemeijer: Alphen aan den Rijn. Albaniana 2001-2002. Opgravingen tussen de Castellumstraat, het Omloopkanaal en de Oude Rijn . Nijmegen 2004, ISBN 90-802647-5-X , ( also digitized as pdf ).

- ↑ a b Jan Kees Haalebos, Paul Franzen et al .: Alphen aan den Rijn. Albaniana 1998-1999. Opgravingen in de Julianastraat, de Castellumstraat, op Het Eiland en onder het St.-Jorisplein . Nijmegen 2000, ( also digitized as pdf ), pp. 21–28.

- ↑ Marinus Polak, René PJ Kloosterman, Ryan AJ Niemeijer: Alphen aan den Rijn. Albaniana 2001-2002. Opgravingen tussen de Castellumstraat, het Omloopkanaal en de Oude Rijn . Nijmegen 2004, ISBN 90-802647-5-X , ( also digitized as pdf ), pp. 15–20.

- ↑ Marinus Polak, René PJ Kloosterman, Ryan AJ Niemeijer: Alphen aan den Rijn. Albaniana 2001-2002. Opgravingen tussen de Castellumstraat, het Omloopkanaal en de Oude Rijn . Nijmegen 2004, ISBN 90-802647-5-X , ( also digitized as pdf ), p. 256.

- ↑ Marinus Polak, René PJ Kloosterman, Ryan AJ Niemeijer: Alphen aan den Rijn. Albaniana 2001-2002. Opgravingen tussen de Castellumstraat, het Omloopkanaal en de Oude Rijn . Nijmegen 2004, ISBN 90-802647-5-X , ( also digitized as pdf ), p. 122.

- ^ P. van Rijn: Hout. In: Marinus Polak, René PJ Kloosterman, Ryan AJ Niemeijer: Alphen aan den Rijn. Albaniana 2001-2002. Opgravingen tussen de Castellumstraat, het Omloopkanaal en de Oude Rijn. Nijmegen 2004, ISBN 90-802647-5-X , ( also digitized as pdf ), pp. 216-237.

- ↑ a b C. Svetoni Tranqvilli: De vita Caesarvm libros VIII . VI, 43 to 49.

- ↑ a b c Rob W. Reijnen: Munten. In: Jan Kees Haalebos, Paul Franzen et al .: Alphen aan den Rijn. Albaniana 1998-1999. Opgravingen in de Julianastraat, de Castellumstraat, op Het Eiland en onder het St.-Jorisplein. Nijmegen 2000, ( also digitized as pdf ), pp. 143–148.

- ↑ a b c Fleur Kemmers: Munten . In: Marinus Polak, René PJ Kloosterman, Ryan AJ Niemeijer: Alphen aan den Rijn. Albaniana 2001-2002. Opgravingen tussen de Castellumstraat, het Omloopkanaal en de Oude Rijn. Nijmegen 2004, ISBN 90-802647-5-X , ( also digitized as pdf ), pp. 165–187.

- ↑ Rounding errors.

- ↑ a b c d e f Marinus Polak, René PJ Kloosterman, Ryan AJ Niemeijer: Alphen aan den Rijn. Albaniana 2001-2002. Opgravingen tussen de Castellumstraat, het Omloopkanaal en de Oude Rijn . Nijmegen 2004, ISBN 90-802647-5-X , ( also digitized as pdf ), pp. 122–124 and p. 249f.

- ^ Ester van der Linden: Graffiti . In: Jan Kees Haalebos, Paul Franzen et al .: Alphen aan den Rijn. Albaniana 1998-1999. Opgravingen in de Julianastraat, de Castellumstraat, op Het Eiland en onder het St.-Jorisplein. Nijmegen 2000, ( also digitized as pdf ), pp. 117–120.

- ^ [Coh (ortis)] VI Breuc (orum) cui prae / [est Ti (berius)] Cl (audius) Ampliatus pr (aefectus?) AE 1975, 00632

- ↑ [Coh (ors) VI Bre] uco / [rum 3] AE 2000, 01025a

- ↑ a b Marinus Polak, René PJ Kloosterman, Ryan AJ Niemeijer: Alphen aan den Rijn. Albaniana 2001-2002. Opgravingen tussen de Castellumstraat, het Omloopkanaal en de Oude Rijn. Nijmegen 2004, ISBN 90-802647-5-X , ( also digitized as pdf ), p. 124f. and p. 252ff.

- ^ Nine stamps from Leg (io) IM (inervia) Ant (oniniana) AE 2000, 01025e1 to AE 2000, 01025e9

- ↑ [Te (gularia) T] ra (nsrhenana) F (lavia) coh (ortis) I / [No] bilis f (ecit) AE 2000, 01025b

- ↑ a b c Marinus Polak, René PJ Kloosterman, Ryan AJ Niemeijer: Alphen aan den Rijn. Albaniana 2001-2002. Opgravingen tussen de Castellumstraat, het Omloopkanaal en de Oude Rijn . Nijmegen 2004, ISBN 90-802647-5-X , ( also digitized as pdf ), pp. 125-127 and p. 253.

- ↑ AE 2000, 1023 (print edition of AE still with a different reading, see the entry on the inscription in the Heidelberg Epigraphic Database ).

- ^ Jan Kees Haalebos, Paul Franzen et al .: Alphen aan den Rijn. Albaniana 1998-1999. Opgravingen in de Julianastraat, de Castellumstraat, op Het Eiland en onder het St.-Jorisplein. Nijmegen 2000, ( also digitized as pdf ), pp. 113–118.

- ↑ Official website of the Archeologiehuis Zuid-Holland in Alphen aan den Rijn.

- ^ Official website of the Rijksmuseum van Oudheden in Leiden.

- ↑ Tom Hazenberg et al .: De terugkeer van de Zwammerdam-schepen. Een haalbaarheidsonderzoek Hazenberg AMZ-publicaties 2014 1 (2014).

- ^ The project Zwammerdamschepen en Nationaal Romeins scheepvaartmuseum on the official website of Archeon, ( Dutch ), accessed on May 1, 2018.

- ^ Official website of the Archeon Archaeological Theme Park .