Asciburgium

| Asciburgium | |

|---|---|

| limes | Lower Germanic Limes |

| Dating (occupancy) | Aa) Augustan A.b) Tiberian A.c) Claudian (or earlier) Ad) Neronic A.e) Vespasian up to around 83/85 B) around 230 C) Valentine up to the middle of the 5th century |

| Type | Aa-b) Vexillation fort A.c) Cohort fort A.d – e) Alenkastell B) Beneficiary station C) Burgus |

| unit | Aa-b) unknown Vexillationes A.c) Cohors Silaucensium (or Cohors III Lucensium ?) Ad) Ala I Tungrorum Frontoniana A.e) Ala Moesica Felix Torquata B) unknown C) unknown |

| size | A.) approx. 1.5 to 2.36 ha B) unknown C) 18 × 18 m |

| Construction | A) Wood-earth camp B) Stone construction C) Stone burgus |

| State of preservation | ground monument not visible above ground |

| place | Moers- Asberg |

| Geographical location | 51 ° 25 '54 " N , 6 ° 40' 12" E |

| height | 30 m above sea level NHN |

| Previous |

Vetera (northwest) Calo (north) |

| Subsequently |

Small fort Werthausen (west-southwest; chronologically following) Gelduba (south) |

Asciburgium was a Roman garrison site on the Lower Germanic Limes . Today's soil monument is located in the Asberg district of Moers in the Wesel district on the Lower Rhine . From the early Roman period it monitored the mouth of the Ruhr on the right bank of the Rhine, as well as the presumed precursor of the medieval Hellweg that ran there .

Asciburgium is one of the best-researched auxiliary camps in the province of Germania inferior . The excavations produced rare evidence that Roman troops were present in this region as early as the time of Augustus .

location

The "Burgfeld" of Moers-Asberg, under which the Roman relics are located, belongs to the Middle Lower Rhine Plain. The terrain was formed by movements of the earth's crust and extreme climatic fluctuations towards the end of the Pleistocene . It is characterized, among other things, by the so-called low terraces that flank the Rhine on both sides. Since the terraces were always flood-free, they were ideal for settlement purposes; all Roman military camps between Novaesium and Burginatium were directly on the edge of the terrace.

The edge on which Asciburgium was located can still be seen clearly in today's settlement. From around 30 m above sea level. NHN directly above the edge of the terrace, the terrain drops to the east, towards the old river bed, by about six meters.

The fort was located directly on an arm of the Rhine that was initially navigable in Roman times . When Asciburgium was founded, the main channel of the river had already shifted two kilometers to the east, but the fort still had its own port and was connected to the main traffic channel via the oxbow. The oxbow lake, which began to fall dry in the second half of the first century AD, has silted up today, but is still clearly visible in the terrain and on maps as the “Essensberger Bruch”.

From his position, the garrison secured the mouth of the Ruhr against Germanic attacks from the east, which was also followed by the forerunner of the Hellweg , an old trade route that ran from the left Lower Rhine over the area of today's Duisburg through Westphalia to central Germany. The camp was part of the Lower Germanic Limes and was located directly on the Roman road from Colonia Claudia Ara Agrippinensium ( Cologne ) to Ulpia Noviomagus Batavorum ( Nijmegen ), one day's march from Novaesium ( Neuss legionary camp ) and Vetera ( Xanten ).

The fort and large parts of the vicus are now built over by a modern settlement and are no longer visible.

Ancient sources and the name of the fort square

Tacitus gives the earliest concrete reference to the existence, the function as well as the spatial and temporal classification of Asciburgium in his Histories at the beginning of the 2nd century AD. In connection with the description of the Batavian uprising , he describes how the troops of the rebellious Batavians in 69 attacked the fort area in Asberg on a train from Vetera / Xanten to Gelduba / Krefeld -Gellep:

“Rapiunt in transitu hiberna alae Asciburgii sita; [...] ”

“On their march they plundered the winter quarters of an ala lying in Asciburgium ; [...] "

A passage in Tacitus' Germania written a few years earlier is less meaningful :

“Ceterum et Ulixen quidam opinantur longo illo et fabuloso errore in hunc Oceanum delatum adisse Germaniae terras, Asciburgiumque , quod in ripa Rheni situm hodieque incolitur, ab illo constitutum nominatumque; aram quin etiam Ulixi consecratam, adiecto Laertae patris nomine, eodem loco olim repertam, monumentaque et tumulos quosdam Graecis litteris inscriptos in confinio Germaniae Raetiaeque adhuc extare. "

“By the way, some believe that Ulixes too , on his long and legendary wandering into that ocean, stepped onto the coast of Germania and that the Asciburgium on the banks of the Rhine, which is still inhabited today, was founded and named by him; yes, there was even an altar that was found by Ulixes with the addition of his paternal name Laertes at that very place. "

Only the statement that Asciburgium was situated on the banks of the Rhine and was still inhabited at the time when Germania was written (= 98 AD) provides concrete benefits .

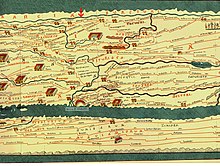

The location information from the Histories of Tacitus is finally specified in the Tabula Peutingeriana , the medieval copy of a Roman road map from the second half of the fourth century. Asciburgium is found here as a Roman road station XIII milia passuum (13 Roman miles = 19.2 km) south of Veteribus (= Vetera) and XIIII milia passuum (14 Roman miles = 20.7 km) north of Novesio (= Novaesium). On the other hand, the late medieval copy of a map by the Greek scientist and geographer Claudius Ptolemy , on which Asciburgium was entered on the right bank of the Rhine, for example in the area of today's Duisburg , caused some confusion . For the original of the Ptolemy map see Askiborgion .

The origin of the name Asciburgium is ultimately unclear. Although there have been different interpretive approaches, with etymological explanations on the basis of Latin, Greek, Celtic and Germanic terms being attempted, none of these attempts at interpretation could really prevail. Due to the port facility, Bechert considered an older interpretation, derived from the Nordic by Heinrich Simon van Alpen, as a “ship's castle” in the sense of a fortified berth as the most plausible. Another way is to derive germ. * Askaz = ash, and germ. * Burg = castle, so literally. "Eschenburg". A relatively general meaning is probably in the sense of " forest castle ", because the Vikings were ascomanni ( ash men ) because they sailed on wooden ships, an ascarius was a fighter with a wooden spear.

Research history

In the written sources of the Middle Ages, the place Asberg is mentioned for the first time in the late 9th century, but isolated finds from the "Burgfeld", which date from the middle of the 6th century, prove that this place was already settled in the early medieval period.

Since Hermann von Neuenahr († 1530) (published posthumously ) there have been repeated reports in the literature (among others by Philipp Clüver and C. V. Weisse) of the existence of the old Roman camp and found since 1591 (for the first time by Johannes Mercator, a grandson of Gerhard Mercator ) the Roman remains that were most likely still visible at this time ( marked as “reliquiae” by Mercator ) also included in various maps.

It was not until 1879, however, before the first soundings were carried out under the direction of the Uerdingen teacher Franz Stollwerck (1814–1885). Systematic archaeological excavations were finally carried out from 1898 under the direction of the Moers District Court Councilor Heinrich Boschheidgen (1864–1924). It was possible to prove beyond doubt the presence of the Roman military and to date the settlement of the place to the first and second centuries AD, but not to determine the location of the fort. Corresponding entries on the excavation plans of this time are of a hypothetical nature.

Following the first archaeological activities, the "Burgfeld" and its Roman legacies were largely left to their own devices and to numerous predatory graves and antique collectors for around five decades . Only a few finds were officially recovered, registered and published. It was not until the beginning of the 1950s that the focus of scientific interest returned to asciburgium. At this point in time, the Lower Germanic Limes in general received more attention within provincial Roman archeology , and in particular a large number of finds from the local gravel pits aroused the interest of the archaeologists and archaeologists of the Rheinisches Landesmuseum Bonn . After two pottery kilns came to light in the "Liesen gravel pit" in 1952 and 1953 and the number of finds increased steadily in the period that followed, the State Museum began regular excavations in 1956, which were headed by Wilhelm Piepers in 1956 and by Siegfried Gollub the following year .

It soon became apparent that further extensive and large-scale excavations would be necessary against the background of the rapidly advancing gravel mining. Since the capacities of the Rheinisches Landesmuseum were already heavily used by the campaigns in Novaesium and Vetera , the further investigations were transferred to the Niederrheinisches Museum of the city of Duisburg, whose director at the time, Fritz Tischler (1910-1967), was in charge of the excavation in the following years took over.

Tischler dug from 1957 to 1967, extending the excavation area from the "Liesen gravel pit" to the south and west. In total, he exposed a contiguous area of more than 3000 m². However, even he did not succeed in determining the location of the fort square. The majority of his excavations moved in the area of the Vicus , the civil camp village just south of today's Moers city limits on the Rheinhausen area (which was incorporated into Duisburg in 1975). Individual short sections of possible defensive trenches identified during excavation investigations could not be put into a plausible overall context.

The discovery of the fort or the fort, as it turned out later, was left to Tilmann Bechert , a young archaeologist from the Lower Rhine Museum. After Tischler's unexpected death in 1967, the systematic investigations in Asberg were initially suspended. Cornelius Ankel (1930–1976) succeeded Tischlers as museum director, while Bechert took care of the processing of the Tischler estate. Increasing construction activity in the Asberg area from 1967 to 1969, during which several buildings were erected without the building site or The excavation pits had been subjected to an archaeological investigation, ensured that the systematic excavations were resumed in 1969. The excavations continued until 1981 and were under the direction of Tilmann Bechert. In 1971 the excavators found the long-sought fort, a few hundred meters north of the areas previously exposed by carpenters on the edge of the lowland of the Essenberger Bruch, an old arm of the Rhine. The planned excavations in Asberg continued until 1981, before the activities of the Niederrheinisches Museum moved away from provincial Roman archeology in 1982 and turned to the city center archeology of medieval Duisburg.

In 1984, under the direction of Dr. Gernot Tromnau, director of the Duisburg Museum at the time, carried out another excavation in the northern burial ground. In the period that followed, further investigations were carried out exclusively in the form of emergency or rescue excavations, which were initially carried out by the Lower Rhine Museum, but later increasingly by the Rhenish Office for Monument Preservation in Xanten or, after the amendment of the North Rhine-Westphalian Monument Protection Act, from 1994 by private excavation companies were.

Findings, history and occupancy

The rectangular and up to 2.3 hectare large first fort was built around 12 BC. BC, built at the beginning of the so-called Drusus offensive , a second camp set up shortly before the turn of the century. The third complex dates from the time of Tiberius (14–37), the fourth fort was built in the time of Caligula (37–41) or Claudius (41–54). In the Batavian uprising it was destroyed in 69 or 70 and then rebuilt again at the beginning of the reign of Vespasian (69-70) as what is now known as the fifth castle.

The camp was then used by auxiliary troops until around 83/85 and then abandoned by the Romans as planned. The reason was probably the silting up of the old Rhine arm near Asberg (today's Essenberger Bruch), which meant that there was no longer any direct access to the river. The garrison was relocated to Werthausen in the area of the neighboring, today's Rheinhausen , where it was used until the middle of the 3rd century. The associated camp village ( vicus ) for the relatives of the soldiers and the veterans, on the other hand, continued to exist for at least a hundred years, as coin finds show. At 230 there was a beneficiary station at this point . Under Valentinian I (354–375) a small, heavily fortified defense system, a so-called Burgus, was built, which was used until the middle of the 5th century.

Early imperial military installations

All five fort complexes that have been proven on the castle field were built as pure wood-earth stores . Since they were systematically put down and leveled by the Romans after their abandonment, they did not leave any visible traces on the terrain. Of the five forts, at least the first three had a rounded floor plan; the typical rectangular shape is only secured for the last. With their Porta praetoria (main gate), all installations were oriented towards the east, towards the Rhine and thus towards the potential enemies, as it was in accordance with the Roman army service regulations. Presumably, the old fortifications of the new fort were left in place until the fort was enclosed by the new fortification. Only then was the old system dismantled and leveled.

Fort I (so-called Drusus Fort)

At the time of its discovery (1971 ff.), Not too many findings from the oldest Asberg military camp (around 12 BC) had been preserved or were available. Only the circular, trough-shaped weir trench could be identified as a double trench in the north of the complex and as a single trench in the southeastern fort area. There was no evidence of a wall or wood-earth wall, and the wall probably had no foundation. The reconstruction of the exposed parts of the trench suggested a camp of just over 1.5 hectares inside. There were only a few pits inside the fort; Findings such as post holes or foundation trenches, which could have indicated interior structures made of wood or timber framing, were completely absent. The troops were probably housed in tents.

As sparse as the traces of the soil were, the findings that could be assigned to the findings were just as significant . The frequent occurrence of an Italian terra sigillata type with a strongly overhanging edge, which has entered the literature as "Service Ia", was striking . This is the oldest known form of sigillata . It was among others in Arezzo ("Arretinische Sigillata") between 30 and 10 BC. And at the end of this production period still in that of Drusus (38-9 BC) around the year 12 BC. Built forts. In military camps that were established from 8/7 BC Were founded, this type of sigillata no longer occurs. Thus, Fort I was definitely one of those (allegedly 50) camps that Drusus had set up shortly before the start of the offensive against the Teutons on the Rhine:

“In Rheni quidem ripa quinquaginta amplius castella dixerit.”

"On the banks of the Rhine himself, he built more than 50 forts."

In this chain of Rhenish forts (in the regional section of the river Novaesium - Gelduba - Asciburgium - Vetera ), Asciburgium probably served less as a basis for carrying out offensive military operations, but rather for defensive surveillance of the Ruhr estuary. No auxiliary unit was entrusted with this task , but a Vexillatio legionis , a detachment of the neighboring legions (from Vetera or from Novaesium), roughly the same number of cohorts . This is supported by the frequently occurring names of soldiers apparently Roman civil rights , which were found as graffiti indicating ownership on numerous sigillata vessels (for example NVMISIVS PRIMVS from Campagna , MERVLA from Tuscany and CORNELIVS). The "Drusus Fort" was leveled in Augustan times, probably shortly before the turn of the century, to make room for the next facility.

Castle II

The second Asberg fort was built in Augustan times, probably shortly before the change from the last pre-Christian to the first post-Christian century. The wood-earth wall was about ten meters in front of the fortification of the older fort, which resulted in an area about 0.2 hectares larger (i.e. about 1.7 hectares). The fence was renewed and reinforced once by replacing the wall, which was reinforced on one side on the outside, with a double-shell fastening with a wider battlement. This reinforcement was probably carried out - probably as a consequence of the clades Variana - in the year 9 AD or in the following year. The complex was surrounded by a simple moat.

The wood-earth wall and the moat could be detected and examined in the north and west of the fort area. In contrast to the fencing, the findings inside the camp were rather sparse, so that no statements could be made about the division and development, which presumably already consisted of a few permanent buildings instead of exclusively tents. However, numerous pits with exclusively Augustan finds were excavated.

As with the "Drusus Fort", the garrison consisted of a Vexillatio legionis whose name has not been handed down . Probably in the early Iberian times, possibly in connection with the recall of Germanicus and the subsequent, defensive redesign of the Roman policy towards Germania, the fort was leveled to make room for a new fortification.

Castle III

The third military camp on the Asberger Burgfeld was established in the years 16 or 17 at the earliest. Its fence was cut several times on the north, south and west sides and the area was examined. The defensive wall was probably a Murus caespiticus , a wall made of sod (caespites) and surrounded by a simple ditch. Like its predecessor, the enclosure of the third fort also had a rounded shape. The storage area was again a good 0.2 ha larger than that of the previous fortification.

In contrast to the two older military camps, numerous traces of the interior development can be found in Fort III; the camp seems to have been the first to have been fully developed inside. Remnants of the foundations of the Principia (staff building, commandant's office), the praetorium (the commandant's residential building), a fabrica (workshop), another farm building with a pottery kiln, as well as traces of some team barracks and numerous pits were archaeologically recorded. The buildings, which were formerly made of half-timbered construction, could only be differentiated from their surroundings on the basis of the different discoloration of the floor, as the wood used for construction had completely disappeared.

The unit occupying the fort was the Cohors Silaucensium ("Silaucenserkohort"), which was originally excavated in the eastern provinces of the empire and which is epigraphically evidenced by the gravestone of one of their soldiers, who came from Syria , in Asberg :

- Tib (erius) Iul (ius) Car-

- etis f (ilius) Sdeb-

- the domo

- Turo missi-

- cius ex coh (places)

- Silauciens-

- iu (m) h (ic) s (itus) e (st) Tib (erius) Iul (ius)

- Antus f (aciendum) c (uravit)

- et Primigenia

- lib (erta) eius anno (rum)

- III h (ic) s (ita) e (st)

Translated: “Tiberius Iulius Sedebdas, son of Cares, from Tire , reservist of the Silaucensian cohort, is buried here. Tiberius Julius Antus has taken care of what was necessary. Primigenia, his freedwoman , three years old, is also buried here. "

The Cohors Silaucensium was a pure infantry unit. Their strength was just under 500 men. It probably remained stationed in Asberg until the third fort was demolished and was then moved to Bonna ( Bonn ), where it is also documented epigraphically.

The backfilling of the moat and the pits inside the fort showed a mixture of Italian and South Gallic sigillates , with the South Gallic goods clearly dominating. The most recent coins from the filling material were two coins of the Caligula (37–41). It can be assumed with some certainty that the fort was leveled in the early Claudian period, in the forties of the first century of our era, to make room for a new facility. The demolition and new construction are probably related to the construction work of the Gnaeus Domitius Corbulo , legate of the Exercitus Germaniae Inferioris , of the Upper Germanic Army, in the years 46/47 to 50. However, the deployments of the years 42/43, which were in preparation for the conquest Britain served as a cause cannot be entirely ruled out.

Castle IV

In place of Cohors Silaucensium entered early Claudian period (about 41 n. Chr.) With the Ala I Tungrorum Frontoniana first time an Ala , a cavalry unit of nearly 500 Manpower, originally in the field of tungri had been dug and the nickname Frontoniana wore . Their existence is also secured by the grave inscription of one of their riders:

- [---] cin [---] s Dacraio-

- nis f (ilius) [---] VC IS cives

- Tribocus aeques (!) Alae

- [Fro] ntonianae an (n) o (rum) [---]

- st [ipe] ndi (orum) XX [I] V hic situs

- est her (es) fu (nus) f (aciendum) c (uravit)

Translated: “Licinus (?), Son of Dacraio, from Uruncis (?), From the tribe of the Triboker , rider of the Ala Frontoniana,? Years old, 24 years of service, is buried here. His legacy provided the necessary burial. "

The change from an infantry to a cavalry unit alone brought - in addition to the basic strategic background described above - the need to build a new camp due to the larger space requirements and the different structural requirements. The new fort probably also had a rounded shape, although not too much of its outline could be exposed, so that theoretically a rectangular or other floor plan cannot be completely ruled out. The traces that the fourth Asberg fort had left in the ground were not as numerous and clear as those of the previous complex. The trench could only be cut in two places, the defensive wall or wall was not detectable at all. Inside the military camp, too, only a few remains of buildings were clearly identifiable, including parts of crew barracks and a few pits. The frequent occurrence of harness parts in the retentura (rear part of the storage area) indicates that horse stables existed there. The sigillate finds consisted exclusively of South Gallic goods, there was no admixture of Italian sigillata.

Fort IV existed for two decades and probably came to an end during the Batavian revolt (69-71 AD) under Iulius Civilis . A surface-covering leveling layer, interspersed with charcoal fragments and bricked clay, speaks at least for a smaller, if not extensive fire, and could thus confirm the report of Tacitus, according to which the camp was supposed to have been taken by the troops of the Civilis in autumn 69.

The Ala I Tungrorum Frontoniana , found in Lower Germany in 71 AD, was then briefly in Dalmatia and then in Pannonia in 73 AD the auxiliary fort of Aquincum was built.

Fort V

The Ala I Tungrorum Frontoniana was stationed in Pannonia after the events of the Four Emperor's Year and replaced by the Ala Moesica Felix Torquata from Moesia , which is also documented epigraphically in Asberg:

- DOM [3 e] qu [es] alae

- Moe [sicae tu] r (ma) Ru [fi] ni

- cives [3] V [3 s] tip (endiorum)

- XX [

Translated: "Dom ... (?), Rider of the Ala Moesica, from the Tower of Rufinus, from the tribe of ...? ..., 2? Years of service, ... "

This new occupancy and the associated new construction of the Asberg garrison is one of the reorganization measures at the beginning of Vespasian's reign, with which he stabilized the situation in the area of the Lower Germanic army (Exercitus Germaniae Inferioris) . The fifth camp of Asciburgium is the best known of all Asberg forts in terms of its defense. It had the outline of a rectangle tending towards a weak parallelogram, which with its internal dimensions of around 148 m × 160 m covered an area of 2.36 hectares. It was surrounded by a three-meter-wide mud wall with foundations, in front of which there was a double moat on the north, south and west sides. On the praetorial front facing the Altrheinarm in the east , the ditch presumably suspended because the fort there seemed to be adequately protected by the wall and the water of the Rhine arm. With the Porta praetoria (main gate) in the east and the Porta principalis sinistra (left side gate) in the north of the complex, two of the four camp gates could be archaeologically recorded.

It has not been clarified with certainty which components of the generally known interior development are to be clearly assigned to Fort V, although a complete interior development of this camp can be assumed. However, as it is located in the topmost layer, which already merges into the humus cover, this is strongly disturbed by repeated plowing over.

The fort existed until the early reign of Domitian (81–96), which appears to be secured by the final coin from the fort area, a coin from the years 81/82. The reason for the abandonment of the Asberg garrison was probably the increasing siltation of the old Rhine arm, which meant that year-round access to the main channel was no longer guaranteed. So Asciburgium lost its former strategic importance. The Ala Moesica was relocated to Upper Germany , in the Wetterau , from there was possibly involved in the wars of Domitian against the Chatten (83-85) and is then attested in the Wetterau castles Echzell and Butzbach of the Upper Germanic Limes .

Early and high imperial as well as late antique military installations

Small fort in Werthausen in Duisburg-Rheinhausen

A small fort in the nearby Duisburg - Rheinhausen district of Werthausen took over part of the functions of the fort in Asciburgium. After this had been given up around the years 83/85, it was probably necessary to control the geographically and strategically important mouth of the Ruhr on the opposite bank of the Rhine from another point. Therefore, in Flavian times, perhaps immediately after the Asberg garrison had withdrawn, which would be supported by some of the finds from Werthausen, the Rheinhausen fortifications were built towards the end of the century at the latest. The fortification in Werthausen had the shape of a slightly shifted rectangle and was surrounded by a 1.2 m to 1.3 m wide defensive wall. With its dimensions of 38 m × 44 m (internal dimensions), the wall encompassed a usable area of just 0.17 hectares, with which it offered a vexillatio with a maximum strength of two centuries (160 men). This garrison served its purpose for around 150 years and was abandoned around the middle of the third century.

Limesstrasse and beneficiary station

About the exact course and structure of the Limesstraße (also: " Rheintalstraße "), which in its Lower Rhine section the Colonia Claudia Ara Agrippinensium or the legionary camp Apud Aram Ubiorum ( Cologne ) with the Colonia Ulpia Traiana and the legionary camp Vetera ( Xanten ) and affected the auxiliary fort in between in its course, is not known too much. Roads paved with stones were rare in Lower Germany, the road surface mostly consisted of gravel, which often occurs in the region, often in several layers on top of each other. The road body was curved towards the middle, so that water could flow off on both sides into the drainage ditches made there. According to regulations, the total width of a via publica , a public street, should be at least 40 Roman feet (= 11.84 m), but it could also be more than double that.

In 1965 Fritz Tischler cut the Römerstrasse near Asberg over a length of 22 m, in 1975 Tilmann Bechert succeeded in uncovering a cross-section of the street in its full width. This revealed a 7.0 m to 8.2 m wide, slightly curved in the middle of the road body made of six layers of gravel, between which there were leveling layers of sand and clay. The finds from the lowest layer of gravel indicated that the paved road was built under Tiberius, an unpaved route was probably already under Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa in the years 20/19 BC. Have been created. The body of the road rose up to a meter from the adjacent land. On both sides the gravel packs were framed by rows of fascines made of sharpened oak stakes interwoven with brushwood.

(222-235)

Since a consecration stone of the beneficiary Caius Catonius Respectus was found in the Asberg area in the 19th century , which could be dated exactly to the year 230, the existence of a beneficiary station in Severan times was considered certain:

- I (ovi) O (ptimo) M (aximo)

- C (aius) Catonius

- Respectus

- b (ene) f (iciarius) co (n) s (ularis)

- Prisciliano

- et Agricola

- co (n) s (ulibus)

Translated: "(In honor of) Jupiter (sws), the best and the highest, (set) Gaius Catonius Respectus, beneficiary of the governor, (this altar), under the consulate of Priscillianus and Agricola."

The beneficiaries were a kind of street police made up of deserving principales (non-commissioned officers) of a legion who were released from normal service. The beneficiaries of Asberg were probably members of the Legio XXX Ulpia Victrix stationed in Vetera , but they were not under the command of the legionary legate, but that of the governor in the CCAA . It would take until the end of the 1950s before Fritz Tischler succeeded in locating the beneficiary station in Asciburgium with some probability. The finds from the early third century, which are not very common in Asberg, concentrated on an area of the Roman road where it bent slightly from SSE to SSW. Hermann Boschheidgen found remains of the foundations and walls here as early as 1898. Tischler made a 60 m long exploratory cut through which further wall remains, architectural fragments and parts of a mosaic floor made of white limestone and red bricks were exposed. The overall connection remained unclear, but later found remains of the foundations indicated that the Asberg beneficiary station is probably to be found at this point.

Guard station on the "Dachsberg" near Duisburg-Baerl

In the years 1952/1953 Fritz Tischler dug up remains of Roman buildings on the "Dachsberg" in the Baerler district of Lohmannsheide, (a good five kilometers as the crow flies from Asciburgium, but still in the context of the Asberg findings), which he mistakenly took for the remains of one Villa Rustica stopped. The finds, which allowed the complex to date to the period between 150/160 and 230/240, were clearly of a military nature.These included two parts of pila (throwing spears), military clothing accessories and numerous terra sigillata fragments of the drag type . 45. The building complex, the exposed main part of which was a 16.3 × 8.5 m house, with its distance of around four kilometers from the Rheintalstrasse is unlikely to have been a street station . Tilmann Bechert rather saw the similarity of the findings to those made by Ursula Heimberg in Bergheim - Kenten , the function of the facility in that of a guard who, after the withdrawal of the Asberg garrison, next to the small fort in Werthausen in the south, the northern protection of the Asberg area could have taken over.

Late antique Burgus

After the Franks and Alamanni had repeatedly crossed the Rhine and Danube and plundered the Roman border areas between 365 and 368, Emperor Valentinian I (364–375) implemented a comprehensive fortress building program from 369 onwards, including the construction numerous Burgi the situation on the Germanic borders should be stabilized again:

“At Valentinianus magna animo concipiens et utilia, Rhenum omnem a Raetiarum exordio ad usque fretalem Oceanum magnis molibus conmuniebat, castra extollens altius et castella turresque adsiduas per habiles locos et oportunos, qua Galliarum extendituris longitudo: non positively subquam a etiam barbarumen longitudo . ”

“ Valentinian made important and beneficial plans. He had the entire Rhine, beginning from Raetia to the Strait of the Ocean , fortified with large dams and erected military installations and forts at the top, as well as towers at close intervals at suitable and favorable locations as far as the Gaulish lands stretched. Sometimes buildings were built across the river where it touched the land of the barbarians. "

Asberg's last military installation belongs in the context of this building program, which was largely completed in 371 on the Rhine border. The Asberger Burgus was built exactly where the southeast corner of the imperial fort had been. It consisted of a massive residential tower, an outer perimeter wall and a moat. The external dimensions of the inner tower fluctuated only slightly between 18.1 × 12.4 m and 18.3 × 12.4 m, the thickness of its walls was 2.7 to 3.2 m. Inside the tower there were four 1.2 m thick arrows with a square floor plan. The surrounding wall was one meter thick and was possibly (as with other comparable Burgi ) reinforced with eight round towers. In addition to its military function, the Burgus also served to protect the population in troubled times. It was abandoned in the fifth century, but was still visible as a ruin for centuries and probably gave its name to today's Burgfeld.

Civil settlements and facilities of civil and military infrastructure

port

The location of Asciburgium on an old, but still navigable arm of the Rhine at the time the fort was founded, almost inevitably implied the existence of a port, if one takes into account that in ancient times the transport of people, animals and heavy goods by water was much cheaper than by land . These basic considerations were supported by the findings of several anchors that may have come from ships that landed in Asciburgium.

Underneath was a mighty stick anchor with a weight of almost three hundred pounds, which was found in the area of Duisburg- Homberg , at the level of the former approach to the Asberg arm of the Rhine. The anchor rod was made of lead and was marked with the inscription "LV", which could have been a property note, but could possibly also be interpreted as a reference to the L (egio) V stationed in Vetera up to the year 69 . The Asberg harbor had therefore been suspected in various places since the 19th century. However, none of these assumptions could be archaeologically confirmed until, in 1974, in advance of the construction of an expressway, the old bank area was systematically searched for bombs from the Second World War. During these investigations, the existence of the port was confirmed when a row of huge oak beams up to four meters long in a lintel position were found immediately in front of the northeast corner of the fort on an area of 12 × 15 m, which apparently belonged to the construction of the Asberg port facility.

This facility did not have a continuous quay constructed from vertical and horizontal beams (as it was known, for example, from Colonia Ulpia Traiana ) that the ships could call at directly, but rather consisted of groups of posts erected in the shape of a dolphin in front of the shore line, between which the ships were moored from there to lay footbridges ashore across the shallow bank zone. At the actual edge of the bank (perhaps in front of the Porta praetoria ) there was probably a pier supported by several rows of stakes, which could be extended further into the water with relative ease as the siltation increased. The bank edge itself was paved with gravel and clay and stabilized with wooden posts. This construction was renewed at least once, according to the finds probably most recently in Flavian times. Not long afterwards, the siltation of the arm of the Rhine was likely to have progressed so far that it was no longer navigable all year round. This circumstance should ultimately have led to the abandonment of the Asberg garrison.

Civil settlement

The civil settlement of Asciburgium is divided into two temporally consecutive, spatially separated areas. To the west and above all to the south of the early imperial military camps, between the Limesstrasse in the east and the lower terrace in the west, was the fort vicus . In addition, traces of a street village were found along the road . The coin series for the civilian settlement areas begins with republican denarii and ends with a sesterce by Clodius Albinus (governor in Lower Germany around 190, co-regent (Caesar) 193–195, counter-emperor 195–197).

Fort vicus of the 1st century

As with almost all Roman military posts that were not only temporarily occupied, a vicus soon formed around the Asberg garrison, a civil settlement in which relatives of the soldiers as well as traders, craftsmen, bar owners (from Canabae derives the word " Pub ”), brothel operators and other service providers settled down. Its buildings, mostly elongated with their gables facing the street, so-called strip houses , were lined up along the streets leading out of the fort. Workshops and shops were located in the front parts of the building facing the street, living and utility rooms and stables were located in the rear areas. The center of gravity of the vicus of Asberg was found mainly in the south of the fort site, north of the camp there were no corresponding findings. The datable find material was dominated by Italian and South Gallic terra sigillata, while Central and East Gallic goods were significantly less common.

The fort village arose in the Augustan period, but not directly together with the Drusus fort, but only in the period of the second camp, shortly after the turn of the century. Its heyday, in which it probably had around 1500 inhabitants (not including the 500 soldiers of the fort), experienced - as evidenced by the quantity and quality of the finds - in the Claudian-Neronian period, before it was destroyed by the Batavians in 69. Within the so-called main construction phase 1, the time between foundation and destruction, two intermediate construction phases can be differentiated. Among other things, the alignment of the strip houses on the arterial road changed. During the first decades of its existence, the vicus was also surrounded by a ditch and probably also by a turf wall or an earth wall, which were leveled in during the Claudian era. The second main building phase was early Vespasian and was built at the same time as the fifth fort around AD 70.

Of the economic structures that must have existed on a larger scale, only a pottery with two kilns has been unearthed, in which simple utility ceramics were produced around the middle of the second century. No thermal baths or cult districts have been archaeologically proven for any of the construction phases, but their existence - analogous to the findings of other Vici - must be assumed. The lack of relevant findings is probably due to the fact that the Tischler excavations, which extended over around 3000 m², only a small part of the settlement could be exposed.

2nd century civil settlement

After Asciburgium had been abandoned by the military around 83/85, a new, purely civilian settlement center arose along the Limesstrasse in the form of a street village about 400 m long. No closed area of this area of the vicus has yet been exposed; its extent could only be proven on the basis of individual findings and the scattering of the finds from the second century. At that time, the vicus must have had a certain importance and / or attractiveness, as several legionary veterans from Vetera settled there with their families after their discharge from military service. Towards the end of the second century, Asciburgium was hit by a German invasion. This is evidenced by layers of fire and layers of destruction, as well as the series of coins that ends with a sesterce of Commodus from the year 181 followed by an isolated sesterce of Clodius Albinus (minted 194/195). It seems plausible that a civilian settlement also existed in Asciburgium up until the time of the beneficiary station, but there are no corresponding findings and only small amounts of finds from the early third century.

Burial grounds

The excavation findings so far indicate a total of two larger burial fields for the fort and the civil settlements, which are located in accordance with the provisions of the Twelve Tables Act

“Hominem mortuum in urbe ne sepelito neve urito.”

"The dead may not be cremated or buried in the city."

north and south outside the military and civilian settlement area along the Limes road towards Vetera and Gelduba . The northern burial ground extended mainly to the west, the southern one and a half kilometers on either side of the road. So far around 150 cremation graves have been found in the northern cemetery and around 220 in the southern cemetery.

The proportion of bust burials at the Asberg graves was exceptionally high (compared to other Roman necropolises) .

“Bustum… proprie dicitur locus, in quo mortuus est combustus et sepultus…; ubi vero combustus quis tantummodo, alibi vero est sepultus, is locus (from urendo) ustrina vocatur… ”

“ Bustum is specifically the place where the dead was burned and buried…; but where someone has only been burned but buried in another place, this place (derived from the process of burning) is called Ustrina . "

The Busta was a type of burial that was probably not of Italian but of Gallic origin. During the burial of the bus, the body was cremated on a pyre that was piled up immediately above the open grave. When the burning pyre burned down and finally collapsed, the heat also radiated downwards and to the sides and led to the floor and walls of the grave being bricked up. The reddish bricks and the remains of charcoal from the pyre are the cause of the typical black and red discoloration of this type of burial in the archaeological evidence.

Northern burial ground

The northern necropolis, which also includes a few isolated graves on the "Burgfeld" itself, was, in addition to a few individual finds, mainly in two campaigns, in 1959/60 under F. Tischler and in 1984 under Gernot Tromnau (the then director of the Lower Rhine Museum of the City of Duisburg). The exact type of burial could be determined for 99 of the 102 cremation graves in the second campaign. There were 59 fire rubble graves (= 57.8%), 27 Busta (= 26.5%) and 13 urn graves (= 12.8%). Three graves (= 2.9%) could not be assigned. In the case of the graves of the first campaign, the proper documentation suffered from the adverse circumstances of the excavation, which meant that to a large extent they had to be content with simply rescuing the grave inventory. The only Asberg brick plate grave comes from the individual grave finds in the castle field . Only a small part of the ceramics in the grave inventory came from the late first and by far the greater part of the second century; Trajan and Hadrian coins dominated among the coins found . The northern burial ground was therefore certainly not created until the first half of the second century, after the troops had withdrawn, and was used exclusively for the burial of residents of the civilian settlement.

Southern burial ground

In the southern necropolis, apart from a few older individual finds, the largest number of graves, 213 burials, were examined in the years 1977/1978 in connection with road construction work. In the process, two excavation campaigns uncovered an area totaling over 2,000 m². In the north and west, the uncovered area was surrounded by a ditch. Beyond this trench, no more burials could be detected, so that between the Roman road and the western trench there was a width of the burial field of around 70 m. The type of grave could be determined in 199 of the total of 213 graves. There were 86 fire rubble graves (= 40.4%), 85 busta (= 39.9%) and 28 urn graves (= 13.1.1%). 14 types of burial (= 6.1%) could no longer be determined. In the terra sigillata from the grave inventory, southern Gaulish goods from the second half of the first century dominated. The series of coins began with an ace from Claudius and ended with two aces from Hadrian, with a focus on the Flavian to Trajan times. the majority of the fibula types came from the second half of the first century. Overall, such a picture emerged, according to which the southern necropolis was mostly occupied in the last third of the first and beyond that only to a small extent at the beginning of the second century.

Two of the most prominent finds from the southern burial ground, the tombstone of Licinus (see above, Fort IV) and the Polla Matidia stone were found in 1768 and 1906 respectively. The inscription on the Matidia stone reads:

- Polla Matidia Sp (uri) f (ilia)

- Olumphia (!) Ann (orum) XXX

- hic sita est

- L (ucius) Iulius L (uci) f (ilius) Fal (erna)

- veteranus leg (ionis) II Aug (ustae)

- d (e) p (ecunia) s (ua) f (aciendum) c (uravit)

Translation: “Polla Matidia, daughter of Spurus, called Olymphia, 30 years old, is buried here. Lucius Iulius, son of Lucius, from the Falerna electoral district, veteran of Legio II Augusta , provided the necessary with his own money. "

Lucius Iulius probably came from Italy (only there the Falerna tribe is documented) and should have joined the 2nd Legion shortly before the turn of the century, which at that time was still stationed in the province of Hispania ulterior . When the Legion was posted to the clades Variana (9 AD) to reinforce the Rhine Army, he came with her to the Lower Rhine and will probably be out of active service shortly after the Germanicus campaigns (14-16 AD) be out because he remained as a reservist in Asberg instead of being transferred to Argentorate with the Legion . With him was Polla Matidia, who probably came from Hispania and was probably his Concubina . The stage name "Olymphia" indicates that she was a dancer, singer or actress who belonged to the Legio II train and came to Germany with them from Spain. In any case, Lucius Iulius was so attached to her that he erected her de pecunia sua (with his own money) a tomb, for which he would have been without being her heir (in this case the epitaph H (eres) F (aciendum) C ( uravit) - "Your legacy has taken care of what was necessary" had to read) would not have been obliged.

Finds from Asciburgium

|

|

|

| South Gallic drag- type terra sigillata . 30 from Asciburgium ( Museum Burg Linn , Krefeld ) |

Rib bowl from the southern burial ground (Museum Burg Linn, Krefeld) |

Rib bowl from the southern burial ground (Museum Burg Linn, Krefeld) |

Monument protection

The fort, the grave fields and the area of the fort vicus are ground monuments according to the law for the protection and maintenance of monuments in the state of North Rhine-Westphalia (Monument Protection Act - DSchG) . Investigations and targeted collection of finds are subject to approval according to § 13 DschG. Incidental finds are to be reported to the monument authorities.

Lost and found and special exhibitions

The extensive finds from Asciburgium are mainly in the Duisburg Cultural and City History Museum , under whose direction the Bechert excavations from the 1960s to 1980s were carried out, in the Rheinisches Landesmuseum Bonn and in the Lower Rhine Landscape Museum at the Burg Linn Museum Center in Krefeld .

The Museum Duisburg presented the current status of the investigations at the time in the special exhibition "ASCIBURGIUM - A Roman military settlement on the Lower Rhine", which was designed by the archaeologist Andrea Gropp and which was under scientific advice from Tilmann Bechert, which ran from September 2013 to March 2014. In addition to exhibits (including finds from the last excavation years that have not yet been shown), the everyday life of the people of that time was documented. The visitors were able to get a detailed overview of the historical framework and the history of research using the exhibits and maps and overview material of the most important sites. Excavation finds and historical events were placed in a context of the Roman era on the Lower Rhine until the end of the Western Roman Empire.

Further finds, in particular those from the first excavations by Hermann Boschheidgen, are in the Moers Castle Museum. There was also a special exhibition “Living and Dying in a Roman Military Settlement” from June 17, 2014 to October 5, 2014 in cooperation with the Duisburg Museum of Culture and City History.

See also

swell

literature

- Tilmann Bechert : Asciburgium - excavations in a Roman fort on the Lower Rhine. Braun, Duisburg 1974 (= Duisburger Forschungen, Vol. 20), ISBN 3-87096-032-9

- Tilmann Bechert: Moers-Asberg and Duisburg-Rheinhausen. Roman auxiliary fort. In: Heinz Günter Horn (Ed.): The Romans in North Rhine-Westphalia. Licensed edition of the 1987 edition. Nikol, Hamburg 2002, ISBN 3-933203-59-7 , pp. 559-568

- Tilmann Bechert: The Romans in Asciburgium. Braun, Duisburg 1989, ISBN 3-87096-047-7 (= Duisburg research, vol. 36)

- Tilmann Bechert: Two thousand years of the Asciburgium. The history of the Roman forts on the "Burgfeld" in Moers-Asberg. Gronenberg, Gummersbach 1992, ISBN 3-88265-179-2 (popular science presentation).

- Tilmann Bechert: Asciburgium and Dispargum. The Ruhr estuary between late antiquity and the early Middle Ages . In: Thomas Grünewald and Sandra Seibel (eds.): Continuity and Discontinuity. Germania inferior at the beginning and at the end of Roman rule . De Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2003, ISBN 3-11-017688-2 (= Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde, supplementary volume 35), pp. 1–11.

- Tilmann Bechert: Finds from Asciburgium - Asciburgium fort, excavations in Moers-Asberg 1965–2011 . Publishing house Dr. Faustus, Duisburg 2011, ISBN 3-933474-77-9

- Hermann Boschheidgen: Asciburgium. An excavation and observation report . In: Bonner Jahrbücher 104, 1899, ZDB -ID 217210-0 , pp. 136-163.

- Günter Krause: A late Roman Burgus from Moers-Asberg on the Lower Rhine . In: Sources for West German Prehistory and Early History Volume 9, Habelt, Bonn 1974, ISSN 0079-9149 , pp. 115–165

- Franz Stollwerck: The old Germanic branch and Roman station Asciburgium, Burgfeld-Asberg near Mörs . Self-published, Uerdingen 1879 ( digitized edition of the University and State Library Düsseldorf ).

- Fritz Tischler: Contributions to Asciburgium Research . Mercator-Verlag, Duisburg 1959 (= Duisburger Forschungen, Vol. 2), ISSN 0419-8026 , pp. 162-188

The scientific publication of the find material was carried out by T. Bechert et al. in the multi-volume series "Funde aus Asciburgium" since 1973. The older issues are nowadays only available in antiquarian versions or in scientific libraries.

- 1 Tilmann Bechert: Roman fibulae of the 1st and 2nd centuries AD. 1973

- 2 Michel Vanderhoeven: Terra Sigillata from Central and Eastern Gaul. The vessels decorated in relief. 1974

- 3 Michel Vanderhoeven: The potter's temple. 1974

- 4 Tilmann Bechert: Stone monuments and vessel inscriptions. 1976

- 5–7 Michel Vanderhoeven: Terra Sigillata from southern Gaul. The vessels decorated in relief. 1975-1988

- 8 Joachim Gorecki: Coins from Asberg. 1981

- 9 Tilmann Bechert and Michel Vanderhoeven: Pottery stamps from southern Gaul. 1988

- 10 Sophie M. van Lith: Glass from Asciburgium. 1987

- 11 Bernd Liesen: Lamps from Asberg. 1994

- 12 Gabriele Rasbach : Roman-era graves from Moers-Asberg, Wesel district. Excavations in 1984 in the northern burial ground. 1997

- 13 Christian Fleer: Stamped bricks from Asberg. 2003

- 14 Sabine Deschler-Erb: Animals in Asciburgium. 2007

- 15 Pia Eschbaumer: The Italische Sigillata from the fort area of Asciburgium. 2010

- 16 Tilmann Bechert: Asciburgium fort. Excavations in Moers-Asberg 1965–2011. Part I: Introduction, Methodology, History. 2012

- 17 Eckhard Deschler-Erb: Roman military equipment from the fort and vicus of Asciburgium. 2012

Web links

Remarks

- ↑ With the excavations ASC IX / 1965 and ASC X / 1965, Tischler had already cut the southeast corner of the camp twice, but did not recognize the significance of the findings.

- ↑ “Porta praetoria semper hostem spectare debet.” Translation: “The Porta praetoria should always look at the enemy.” (Hyginus Gromaticus: Liber de munitionibus castrorum . 56.)

- ↑ “Porta autem quae appelantur praetoria aut orientem spectare debet aut illum locum qui ad hostes respicit.” Translation: “The gate, however, which is called the praetoric, should either look to the east or to that place that looks around to the enemy. " ( Flavius Vegetius Renatus : Epitoma rei militaris . I, 23.)

- ^ Excavations ASC XX / 1971, ASC XXII / 1972 and ASC XXXIII / 1980-81.

- ^ Excavations ASC XVI / 1970 (in the west), ASC XXVIII / 1975-1976 (in the south-west) and ASC XXXIII / 1980-1981 (in the north).

- ^ Excavations ASC XI / 1965, ASC XII / 1972, ASC XXVIII / 1975-76, ASC XXXII / 1979 and ASC XXXIII / 1080-81.

- ↑ Place of storage: Rheinisches Landesmuseum Bonn.

- ↑ Today's Illzach in Alsace.

- ↑ The inscription stone is lost.

- ↑ During the campaigns ASC XXXI / 1979 in the south and ASC XXXIII / 1980-81 in the north of the plant.

- ↑ Since the Flavian period she was stationed first in Aquincum , then in Carnuntum and in the late 1980s in Campona ( Nagytétény ). It is attested in Britain from the 2nd century onwards. After Barnabás Lorinc and Sándor Petényi: Two new military diplomas from Pannonia . In: Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik 101 (1994), pp. 197–204 ( PDF ), as well as AE 1997, 1001 u. a.

- ↑ Translated: "Mösische cavalry unit with the nickname the lucky one, the one awarded with torques ."

- ^ Excavations ASC IX / 1965, ASC X / 1965, ASC XX / 1971, ASC XXII // 1972 and ASC XXXIII / 1980-81.

- ↑ At about 51 ° 25 '20 " N , 6 ° 42' 40" O .

- ↑ The measurement over seven meters comes from the 1975 excavation by T. Bechert; F. Stollwerck claims to have determined 8.2 m in the 19th century. Franz Stollwerck: The old Germanic branch and Roman station Asciburgium, Burgfeld-Asberg near Mörs . Uerdingen 1879, p. 23.

- ↑ At about 51 ° 25 '43 " N , 6 ° 40' 4" O .

- ↑ At about 51 ° 28 '56.5 " N , 6 ° 40' 14.5" O .

- ↑ At about 51 ° 25 '51.75 " N , 6 ° 40' 17.25" O .

- ↑ At 51 ° 25 '59 " N , 6 ° 40' 18" O .

- ↑ a b Status: 1989.

- ↑ At about 51 ° 26 '2.25 " N , 6 ° 39' 53.75" O .

- ↑ From about 51 ° 25 '31 " N , 6 ° 39' 57" O to 51 ° 24 '59 " N , 6 ° 40' 1" O .

Individual evidence

- ^ Renate Gerlach, Thomas Becker, Jutta Meurers-Balke , Irmela Herzog: Das Rhein-Limes-Projekt. Where was the Rhine in Roman times? . In: Andreas Thiel (ed.): New research on the Limes. 4th specialist colloquium of the German Limes Commission 27./28. February 2007 in Osterburken . Theiss, Stuttgart 2008, ISBN 978-3-8062-2251-7 (= contributions to the Limes World Heritage Site, 3), pp. 9–17, with further literature.

- ↑ a b Tilmann Bechert: Landscape and location . In: Ders .: The Romans in Asciburgium . Braun, Duisburg 1989, ISBN 3-87096-047-7 (Duisburger Forschungen, Vol. 36), pp. 37-40.

- ↑ a b c Tacitus, Historiae 4,33.

- ^ Tacitus, Germania , 3.2.

- ^ Tilmann Bechert: The Romans in Asciburgium. Braun, Duisburg 1989, ISBN 3-87096-047-7 (Duisburger Forschungen, Vol. 36), pp. 16-18.

- ↑ Hermann Simon van Alpen: History of the Franconian banks of the Rhine, what it was and what it is now. Volume 2. Oedenkoven & Thiriart, Cologne 1802, p. 519.

- ^ Tilmann Bechert: The Romans in Asciburgium. Braun, Duisburg 1989, ISBN 3-87096-047-7 (Duisburger Forschungen, Vol. 36), p. 34 f.

- ↑ G. Köbler: Germanic dictionary. 2007.

- ↑ Rudolf Kötzschke: The land register of the Werden ad Ruhr abbey Tl. A: The land register from 9. – 13. Century. Bonn 1906, p. 16 A § 3.3 (Rheinische Urbare 2).

- ^ F. W. Schmidt, in: Bonner Jahrbücher 31, 1861, p. 101 and Frank Siegmund: Merowingerzeit am Niederrhein. Rheinland-Verlag, Cologne 1998, p. 275 with plate 57 (Rheinische Ausgrabungen 34).

- ^ Hermann von Neuenahr: De Galliae Belgicae Commentariolvs, nunc primum in lucem editvs . Associated with: Peter van Dieven : Petri Divaei Louanensis De Galliae Belgicae Antiqvitatibvs. 2nd ed., Christoffel Plantijn, Antwerp 1584, p. 15: “Asciburgium… is namely a village on the soil of which various signs of old times can still be found. ... This place is still called Asburg by the locals, an important proof of the truth. ... The farmers call this corridor Burgfeld (Burgensis), because the legend has always gone that there was a castle (burgus) there, the ruins of which (rudera) can be seen in the whole area. "

- ^ Translation after Tilmann Bechert: Asciburgium - excavations in a Roman fort on the Lower Rhine. Braun, Duisburg 1974 (Duisburger Forschungen, Vol. 20), ISBN 3-87096-032-9 , pp. 14-16 and Ders .: The Romans in Asciburgium. Braun, Duisburg 1989, ISBN 3-87096-047-7 (Duisburger Forschungen, Vol. 36), p. 20.

- ^ Philipp Clüver: Germania antiquae libri tres , 1616.

- ↑ C. V. Weisse: Asciburgium in a supplement to the memory of the Moersian antiquities . Continuation article in: Weekly Duisburg, address and intelligence slips set up in the interest of the Commercien der Clevischen, Geldrischen, Meurs and Märckischen also surrounding localities , 1765.

- ^ Franz Stollwerck: The old Germanic settlement and Roman station Asciburgium, Burgfeld-Asberg near Mörs. Uerdingen 1879.

- ^ Hermann Boschheidgen: Asciburgium. An excavation and observation report. In: Bonner Jahrbücher 104, 1899, pp. 136 ff.

- ↑ a b c d Tilmann Bechert: excavations and research . In: Ders .: The Romans in Asciburgium. Braun, Duisburg 1989, ISBN 3-87096-047-7 (Duisburger Forschungen, Vol. 36), pp. 41-52 and Ders .: Asciburgium - excavations in a Roman fort on the Lower Rhine. Braun, Duisburg 1974 (Duisburger Forschungen, Vol. 20), ISBN 3-87096-032-9 , pp. 29-31.

- ↑ So with August Oxé: Roman tombstone of a woman, found in Asberg (Asciburgium) . In: Bonner Jahrbücher 116, 1907, pp. 19 ff. And Ders .: The Germanic Ala I Tungrorum Frontoniana in Asciburgium . In: Bonner Jahrbücher 133, 1930, pp. 62 ff.

- ↑ Harald von Petrikovits : Observations on the Lower Germanic Limes since the Second World War. In: Saalburg-Jahrbuch 14, 1955, p. 7 ff. And Ders .: The Roman Rhineland. Research since 1945. Westdeutscher Verlag, Cologne 1960 (= Bonner Jahrbücher, supplement 8).

- ^ Fritz Tischler: Contributions to Asciburgium research . Mercator-Verlag, Duisburg 1959 (Duisburger Forschungen, Vol. 2), ISSN 0419-8026 , pp. 162-188.

- ↑ Culture and Local History Museum Duisburg: Asciburgium A Roman military settlement on the Lower Rhine - Museum brochure slow motion , Preface: Susanne summer, museum director Duisburg in 2013, p.3

- ^ A b Tilmann Bechert: The fort and its buildings . In: Ders .: The Romans in Asciburgium. Braun, Duisburg 1989, ISBN 3-87096-047-7 (= Duisburger Forschungen, Vol. 36), pp. 53-108.

- ^ Tilmann Bechert: The Romans in Asciburgium. Braun, Duisburg 1989, ISBN 3-87096-047-7 (= Duisburger Forschungen, Vol. 36), p. 60.

- ^ A b Tilmann Bechert: The Romans in Asciburgium. Braun, Duisburg 1989, ISBN 3-87096-047-7 (= Duisburger Forschungen, Vol. 36), pp. 54-58.

- ^ Hans Dragendorff and Carl Watzinger: Arretinische Reliefkeramik. With a description of the collection in Tübingen . Gryphius, Reutlingen 1948.

- ↑ Florus : Epitoma de Tito Livio bellorum omnium annorum DCC libri duo . II, 30, 26.

- ^ Tilmann Bechert: The Romans in Asciburgium. Braun, Duisburg 1989, ISBN 3-87096-047-7 (= Duisburger Forschungen, Vol. 36), pp. 54-58 and 109 f.

- ↑ Barbara Pferdehirt : The Roman occupation of Germania and Rhaetia from the time of Tiberius to the death of Trajan. Investigations into the chronology of southern Gaulish relief sigillata . In: Yearbook of the Römisch-Germanisches Zentralmuseum Mainz , 33, 1986, p. 228 ff.

- ^ Tilmann Bechert: The Romans in Asciburgium. Braun, Duisburg 1989, ISBN 3-87096-047-7 (= Duisburger Forschungen, Vol. 36), pp. 58-60.

- ↑ a b c Tilmann Bechert: The Romans in Asciburgium. Braun, Duisburg 1989, ISBN 3-87096-047-7 (= Duisburger Forschungen, Vol. 36), p. 61 f.

- ↑ CIL 13, 8593 .

- ↑ Data sheet ( page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. on the website "ubi-erat-lvpa.org" of the University of Salzburg.

- ^ Tilmann Bechert: The Romans in Asciburgium. Braun, Duisburg 1989, ISBN 3-87096-047-7 (= Duisburger Forschungen, Vol. 36), p. 116 f.

- ^ Géza Alföldy : The auxiliary troops of the Roman province Germania inferior . Rheinland Verlag, Düsseldorf 1968, pp. 38 ff. And 188 ff.

- ^ Lothar Bakker and Brigitte Galsterer-Kröll: Graffiti on Roman ceramics in the Rheinisches Landesmuseum Bonn . Rheinland Verlag, Cologne 1975, ISBN 3-7927-0214-2 (Epigraphic Studies, 10), p. 92.

- ^ Tacitus, Annales 11, 18 ff.

- ↑ AE 1931, 30

- ^ Tilmann Bechert: The Romans in Asciburgium. Braun, Duisburg 1989, ISBN 3-87096-047-7 (= Duisburger Forschungen, Vol. 36), p. 117 f.

- ^ Tilmann Bechert: The Romans in Asciburgium. Braun, Duisburg 1989, ISBN 3-87096-047-7 (= Duisburger Forschungen, Vol. 36), pp. 62-64.

- ↑ CIL 03, 09735 .

- ↑ AE 1993, +01307 .

- ↑ Manfred Kandler: The Auxiliary Fort Carnuntum, Volume 29. Austrian Archaeological Institute, Vienna 1997. P. 73.

- ^ Géza Alföldy: The auxiliary troops of the Roman province Germania inferior . Rheinland Verlag, Düsseldorf 1968, pp. 38 ff. And 189 f.

- ^ Géza Alföldy: The auxiliary troops of the Roman province Germania inferior . Rheinland Verlag, Düsseldorf 1968, p. 23 ff. And 178 ff.

- ↑ CIL 13, 8592 .

- ^ Tilmann Bechert: The Romans in Asciburgium. Braun, Duisburg 1989, ISBN 3-87096-047-7 (= Duisburger Forschungen, Vol. 36), p. 120 ff.

- ↑ Hans-Günther Simon and Dietwulf Baatz : Traces of the Ala Moesica Felix Torquata from Upper Germany . In: Saalburg-Jahrbuch 25, 1968, pp. 193-201.

- ^ Tilmann Bechert: The Romans in Asciburgium . Braun, Duisburg 1989, ISBN 3-87096-047-7 (= Duisburger Forschungen, Vol. 36), pp. 64-70.

- ^ Tilmann Bechert: Moers-Asberg and Duisburg-Rheinhausen. Roman auxiliary fort. In: Heinz Günter Horn (Ed.): The Romans in North Rhine-Westphalia. Licensed edition of the 1987 edition. Nikol, Hamburg 2002, ISBN 3-933203-59-7 , p. 567 f.

- ^ Tilmann Bechert: The small fort in Werthausen . In: Ders .: The Romans in Asciburgium . Braun, Duisburg 1989, ISBN 3-87096-047-7 (= Duisburger Forschungen, Vol. 36), pp. 196-200.

- ^ Julianus Egidius Bogaers and Christoph B. Rüger : The Lower Germanic Limes. Materials on its story . Rheinland-Verlag, Cologne 1974, ISBN 3-7927-0194-4 , pp. 132-134.

- ^ Josef Hagen: Roman roads of the Rhine province . 2., rework. and probably edition, Schröder, Bonn 1931.

- ^ Wilhelm Piepers: A profile through the Roman state road Cologne-Jülich-Tongeren, taken in the state forest of Ville, Bergheim / Erft district . In: Rheinische Ausgrabungen 3 (1968), p. 317 ff.

- ^ A b c Tilmann Bechert: Limesstraße and Benefiziarierstation In: Ders .: The Romans in Asciburgium. Braun, Duisburg 1989, ISBN 3-87096-047-7 (= Duisburger Forschungen, Vol. 36), pp. 160-170.

- ^ Tilmann Bechert: New investigations in the Roman fort Asciburgium in Moers-Asberg . In: Rheinische Ausgrabungen '75 , 1976, p. 47.

- ↑ CIL 13, 8588 .

- ^ Hermann Boschheidgen: Asciburgium. An excavation and observation report . In: Bonner Jahrbücher 104, 1899, p. 141.

- ^ Fritz Tischler: Contributions to Asciburgium research . Mercator-Verlag, Duisburg 1959 (= Duisburger Forschungen, Vol. 2), ISSN 0419-8026 , p. 178 and Ders .: Annual Report 1951 . In: Bonner Jahrbücher 155/156, 1955/56, p. 491.

- ↑ Harald von Petrikovits: Roman finds from Baerl . In: Fritz Tischler: Contributions to Asciburgium research . Mercator-Verlag, Duisburg 1959 (= Duisburger Forschungen, Vol. 2), ISSN 0419-8026 , p. 186 ff.

- ↑ Ursula Heimberg: A street station near Bergheim (Erftkreis) . In: Bonner Jahrbücher 177, 1977, p. 569 ff.

- ^ Tilmann Bechert: The military station on the Dachsberg in Duisburg-Baerl . In. Ders .: The Romans in Asciburgium. Braun, Duisburg 1989, ISBN 3-87096-047-7 (= Duisburger Forschungen, Vol. 36), pp. 201-204.

- ↑ Ammianus Marcellinus : Res gestae . 28; 2.1.

- ^ Tilmann Bechert: The late Roman Burgus . In: Ders .: The Romans in Asciburgium. Braun, Duisburg 1989, ISBN 3-87096-047-7 (= Duisburger Forschungen, Vol. 36), pp. 155-159.

- ^ Wilhelm Piepers: Parts of Roman ship anchors from the Lower Rhine . In: Bonner Jahrbücher 174, 1974, p. 561 ff.

- ^ Günter Krause: Roman anchors from Xanten and Duisburg . In: Excavations in the Rhineland '78 , 1979, p. 172 f.

- ^ A b Tilmann Bechert: Port and shore area . In: Ders .: The Romans in Asciburgium. Braun, Duisburg 1989, ISBN 3-87096-047-7 (= Duisburger Forschungen, Vol. 36), pp. 205-215.

- ↑ Sabine Leih: The port of Colonia Ulpia Traiana . In: Martin Müller, Hans-Joachim Schalles , Norbert Zieling (eds.): Colonia Ulpia Traiana. Xanten and its surroundings in Roman times . Zabern, Mainz 2008, ISBN 978-3-8053-3953-7 , pp. 447-469.

- ^ A b c Tilmann Bechert: Fort village and civil settlement . In: Ders .: The Romans in Asciburgium. Braun, Duisburg 1989, ISBN 3-87096-047-7 (= Duisburger Forschungen, Vol. 36), pp. 133-154.

- ↑ Tilmann Bechert: The state of the asciburgium research. Preliminary report on the excavations up to 1971. In: Rheinische Ausgrabungen 12 (1973), pp. 162 ff. And Table 9.

- ^ Tilmann Bechert: Stone monuments and vessel inscriptions. In: Finds from Asciburgium 4 (1976), pp. 20 f.

- ^ Marcus Tullius Cicero : De legibus . 2; 23, 58.

- ↑ a b c d Tilmann Bechert: The grave fields of the fort and vicus . In: Ders .: The Romans in Asciburgium. Braun, Duisburg 1989, ISBN 3-87096-047-7 (= Duisburger Forschungen, Vol. 36), pp. 171-195.

- ↑ Sextus Pompeius Festus : De verborum significatu . 32, 7-11.

- ^ Gernot Tromnau: Excavations in the northern Roman burial ground of Moers-Asberg . In: Excavations in the Rhineland 1982/84 (1985), p. 132 ff.

- ↑ See also Tilmann Bechert: On the terminology of Roman provincial fire graves. In: Archäologisches Korrespondenzblatt , 10/1980, Verlag des Römisch-Germanisches Zentralmuseums , Mainz 1980, ISSN 0342-734X , p. 253 ff.

- ^ Gabriele Rasbach: Roman-era graves from Moers-Asberg, Wesel district. Excavations in 1984 in the northern burial ground. City of Duisburg, Duisburg 1997, ISBN 3-89279-544-4 (= finds from Asciburgium 12)

- ↑ CIL 13, 12075 .

- ^ Tilmann Bechert: Soldiers and civilians . In: Ders .: The Romans in Asciburgium. Braun, Duisburg 1989, ISBN 3-87096-047-7 (= Duisburger Forschungen, Vol. 36), pp. 109-134, especially 111-115.

- ↑ Law for the protection and care of monuments in the state of North Rhine-Westphalia (Monument Protection Act - DSchG) ( Memento of July 18, 2011 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Culture and City History Museum Duisburg: ASCIBURGIUM A Roman military settlement on the Lower Rhine. Culture and City History Museum Duisburg, Duisburg 2013.