Villa rustica

A villa rustica (plural villae rusticae ) is a country house or estate in the Roman Empire . It was the center of an agricultural operation and, in addition to the main building, consisted of farm buildings and outbuildings, most of which were located within a walled courtyard.

term

The term villa rustica is a modern word creation. The word rusticus is an adjective derived from rus (“country”, as opposed to city) and has the meaning “rural”, “peasant”. In addition to the term rus , the words praedium (“good”) and fundus (“farm”) were often used by the Romans to refer to agriculture. The Romans made a distinction between urban buildings (aedes) and rural buildings (villae) . A similar distinction was made between undeveloped land in the city (area) and in the countryside (ager) . Large estates were also called latifundium (from latus = "wide").

historical development

The villae rusticae were not the primary form of agriculture of the Romans from the start. Until the end of the third century BC, mainly small farms, which relied on subsistence farming , were responsible for agriculture. It was only with the territorial gains that the Romans recorded after the victory over Hannibal that there was a slow change in agriculture. The new land that the Romans won was divided into parcels of different sizes and then leased to farmers or to establish colony . If private individuals now took over the rights to this land, they could do anything they wanted with it, even if the state was actually still the de facto owner. The system of inheritance and transmission over time led to more and more land illegally falling into private hands.

With the victory over Carthage , Rome also gained a great reputation in the Mediterranean region and began to increasingly enter into trade relations with other powers. This also led to competition between domestic and imported products. The wealthy owners soon began to rely on an export economy with the aim of making as much profit as possible instead of just being able to support themselves and the family.

Construction and setup

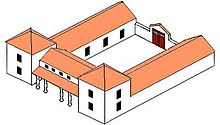

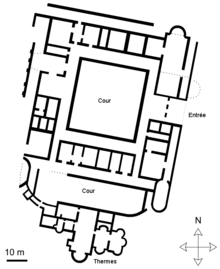

In Italy, the main building of a villa rustica usually comprised a spacious inner courtyard, around which the utility rooms (pars rustica) were grouped, the often two-story residential wing (pars urbana) was usually on the north side of the courtyard. In the Gallic and Germanic provinces , where the majority of the villae rusticae known today were located, the type of building was completely different. In the case of larger complexes, the main house was often designed as a portico villa : the front was divided into the corner risalits and the portico in between (a portico open to the front). The living and working rooms of the landlord and his family were directly adjacent to the portico. Often a larger central room can also be observed along which several room suites were arranged. The question of whether it is a covered hall or an uncovered inner courtyard is largely unanswered and may not be generally answered. Systems of the portico or risalit type are a dominant type of building that can be found very often in medium-sized systems up to the large palatial main buildings such as the Villa Otrang near Fließem.

Larger villas usually had heated bathrooms or bathhouses, and some of the rooms often had to be heated using underfloor heating ( hypocausts ). They typically had a cellar (cella) on either as a storeroom or a home shrine for the Lares served and other protective gods. Sometimes there was also a small temple on the site.

The luxurious living conditions were only accessible to a small upper class. Some smaller courtyards, especially in the area on the right bank of the Rhine, did not have such facilities - here the main building was often just a simple stone building. In many regions such homesteads even form the majority of rural settlements. The so-called patronage system has been suspected as the background for a long time , which was very widespread in rural regions and increased sharply until late antiquity . This would be supported by the relative lack of evidence of slaves in Roman villas in the northwestern provinces and more frequent evidence of colonies in the finds.

The area of a villa rustica could be enclosed with hedges, walls and ditches. This is especially true for military farms in the outskirts of the empire. These protective systems could consist of simple hedges, but in the case of richer villae rusticae they could also consist of walls with towers and bastions and probably associated troops, which could protect the villa rustica . In many cases, however, no courtyard fencing can be made out. The residential building and farm building were enclosed by a fence. Within such an area, in the archaeological findings, there are also houses and stables, wells, threshing areas, gardens and ponds. Burial places were usually outside, mostly on an access road. The fertile Lößebenen of Rhein country and Wetterau were covered with a honeycomb-like system of villae rustica, wherein the distance of the farm buildings is about two to three kilometers. Occasionally it was concluded that a land survey ( centuriatio ) was carried out. So far, however, there is no clear evidence of this.

Due to the structure of the site, Villae Rusticae can be divided into two different types: axial systems and litter yard systems. The decisive factor in this division is the degree of separation between pars rustica and pars urbana . With litter yards, the various buildings are often randomly distributed over the area. There is no real structural concept to be recognized and often no clear distinction between pars rustica and pars urbana. The delimitation is much clearer for axial systems. The pars urbana is often separated from the pars rustica by a small wall or at least a clear border . In addition, a street usually runs through the pars rustica, which shows a certain axiality.

Management

The landlord (dominus) of villa rustica was often a veteran who had retired from military service and who took on supply tasks for the nearby towns and garrisons within the provincial infrastructure. Because of the high cost of transportation, most of the villas were close to the consumers, which explains the large number of villae rusticae in those border provinces where the Roman troops were mainly stationed. If a villa had an average of 50 people, it could at best produce food for 20 other townspeople or soldiers, because these businesses usually only achieved a small surplus. According to this calculation, there should have been around 2000 villas around a city like Carnuntum with 40,000 inhabitants to supply them, even if the farmers here were relieved a little by additional food procurement from trade and fishing. The space that these 100,000 farmers needed, as well as the logistical hurdles for transport and storage, were enormous. The villas delivered their goods up to 50 km to the cities, preferably by cheap water over the rivers.

The property was managed directly by the landlord or with the help of an administrator, usually a slave familiar to the landlord. Depending on the season of the year and the work involved, the latter decided what the farm workers, i.e. mostly slaves (servi) , but also freed persons (liberti) or free, had to do. Most of the landlords stayed away from their rural properties and, if so, only showed up on more important occasions. In the case of larger properties, it was not uncommon for the area to be subdivided into several parcels and then leased to independent farmers. These were then subordinate to the property manager, who cultivated his own plot of land from the main house and at the same time checked the fees of the tenants.

Cultivated products differed depending on the economic orientation of the villa rustica , the location and the nature of the soil. In the provinces, for example in Germania superior , the same products could not be grown as on the Apennine peninsula . Different weather and environmental conditions led to different economic forms. In the Germanic provinces, for example, brown earth and wet soils were not suitable for the transfer of Mediterranean economic forms. Even in areas where the soil made it possible to grow products better, you had to rely on other products when the winters were significantly more severe than in Roman Italy. Olive trees, for example, could not survive the winter north of the Alps at all and when it came to grain, the villae rusticae of the Germanic provinces relied on barley, spelled or rye instead of wheat.

Even then, the products had to be adapted to market requirements. The agricultural producers of the ancient Apennines were in competition with those of the Roman provinces. Tarraconensis (Spain) and Gallia ( Gaul ) were known for exporting wines and oils; In addition, sheep farming was widespread in Gaul and the products associated with it, such as textiles, cheese and salted meat; Aegyptus (Egypt) and other African provinces for grain.

Special form villa urbana

In addition, senators and other high political officials owned huge country estates with correspondingly large country houses, which were often luxuriously furnished and used for summer residence. A villa of this type, in contrast to the purely economic villa rustica , is called villa urbana , i.e. a country house equipped with urban comfort. So far, only one such villa has been found in the area on the right bank of the Rhine, namely in Heitersheim in Baden-Württemberg .

Further use by Teutons

From the second half of the 3rd century there was a steady decline in population in the Germanic provinces ( Germania inferior ) and ( Germania superior ), triggered by the increasing raids of Germanic tribes on the right bank of the Rhine (especially Alemanni and Franks ) on Roman territory. Many villas were abandoned during this period. Further use by newly settled Germanic tribes is difficult to prove archaeologically, as finds from this period cannot in most cases be assigned with certainty to ethnicity. In addition, the Germanic tribes who settled near the border often adopted the Roman way of life, so that there is hardly any evidence for an assignment. In southwest Germany only one case ( Villa rustica von Wurmlingen ) was able to provide reliable archaeological evidence of the secondary use of Roman building fabric by the Teutons. Villae rusticae continued to exist in the 4th and 5th centuries , but in significantly fewer numbers than before.

Individual plants

The villa rustica was the dominant form of rural settlement in the western provinces of the Roman Empire. Villages ( vici ) were much rarer than today and less agricultural. In today's Germany alone, several thousand systems are known through archaeological studies. The size varies from simple subsistence businesses to large manors or even “palace villas”, as they are common in the area around Roman Trier ( Villa von Welschbillig , Kaiservilla von Konz , Trier-Pfalzel ).

The conservation conditions are very different depending on the local conditions. Most of these systems were discovered through aerial archeology , findings accidentally uncovered during construction work or surface finds . Older excavations mostly aimed at exposing the distinctive main building, while more recent investigations mostly include the courtyard area in order to enable statements to be made about the farm's economic activity. Existing parts of the building are comparatively rare and, like the excavated facilities, are often made accessible as a museum, open-air museum or archaeological park. The systems mentioned in the extensive specialist literature are kept in a separate list .

literature

- Werner Tietz: Shepherds - Peasants - Gods. A History of Roman Agriculture. CH Beck. Munich 2015.

- Helmut Bender, Hartmut Wolff (ed.): Rural settlement and agriculture in the Rhine-Danube provinces of the Roman Empire. (Passau university publications on archeology; Vol. 2). Leidorf Verlag, Espelkamp 1994.

- Ursula Heimberg : Villa rustica. Living and working on Roman country estates. Philipp von Zabern, Mainz 2011. (current, material-rich introduction.)

- Karl Heinz Lenz : Rural Settlement. In: Thomas Fischer (Ed.): The Roman Provinces. An introduction to their archeology . Theiss-Verlag, Stuttgart 2001, pp. 58-67.

- Hans Ulrich Nuber : Villae Rusticae. Roman farms and country estates in Baden-Württemberg. In: Imperium Romanum. Rome's provinces on the Neckar, Rhine and Danube. Archaeological State Museum Baden-Württemberg, Esslingen 2005, pp. 270–277.

- John Percival: The Roman Villa. A Historical Introduction. Batsford, London 1988. (on the Roman villa in general.)

- Peter Rothenhöfer: The economic structures in southern Lower Germany. Investigations into the development of an economic area on the periphery of the Imperium Romanum. (= Cologne studies on the archeology of the Roman provinces . Volume 7), 2005.

- Vera Rupp , Heide Birley (ed.): Country life in Roman Germany. Theiss, Stuttgart 2012, ISBN 978-3-8062-2573-0 .

- John T. Smith: Roman Villas. A Study in Social Structure. Routledge, London 2003. (General description of the Roman villa without special consideration of villae rusticae .)

Web links

- Villa rustica - the Roman country estate on the website of the Center for Educational Media on the Internet e. V. (TO)

- Detailed description of the manor house of a villa rustica with many pictures on a private website

- Film about the Villa Rustica Münzenberg-Gambach

Online publications:

- Bilgehan Köhler: Villa rustica Frimmersdorf 49 and Villa rustica Frimmersdorf 131. studies of Roman settlement in the lignite mining area Garzweiler I . Dissertation at the University of Cologne, 2005. On the servers of the University of Cologne and the German National Library

Individual evidence

- ↑ Information from Wolfgang Czysz in: Die Römer in Bayern. Nikol, Hamburg 2005, ISBN 3-937872-11-6 , p. 216.

- ^ Werner Tietz: Villa Rustica. Living and working on Roman country estates . Munich 2005, p. 187 .

- ↑ See also Hans Ulrich Nuber : Villae Rusticae. Roman farms and country estates in Baden-Württemberg. In: Imperium Romanum. Rome's provinces on the Neckar, Rhine and Danube. Archaeological State Museum Baden-Württemberg, Esslingen 2005, ISBN 3-8062-1945-1 , p. 274 with footnotes; Wolfgang Czysz: The civil life in the province. The manors in the country: The villae rusticae in the 2nd century. In: W. Czysz u. a. (Ed.): The Romans in Bavaria. Nikol, Hamburg 2005, ISBN 3-937872-11-6 , p. 220 f.

- ↑ For these buildings and their role in research see: Vera Rupp : The rural settlement and agriculture in the Wetterau and in the Odenwald during the imperial period (up to and including the 3rd century). In: H. Bender / H. Wolff (Ed.): Rural settlement and agriculture in the Rhine-Danube provinces of the Roman Empire. Passau University Writings on Archeology 2 (Passau / Espelkamp 1991/1994) p. 241; H. Bernhard in: Heinz Cüppers (Ed.): The Romans in Rhineland-Palatinate. Licensed edition, Nikol, Hamburg 2002, ISBN 3-933203-60-0 , p. 362 (Enkenbach-Alsenborn); Siegmar von Schnurbein : Perspectives on Limes Research. In: The Roman Limes in Germany. Archeology in Germany special issue 1992, p. 79.

- ^ So already 1970 Dietwulf Baatz : Legal status and administration of the flat country in Roman times ; ders .: The rural settlement in the Roman Empire east of the Upper and Middle Rhine. Gymnasium Beih. 7 (Germania Romana III), 1970 p. 11 and 102. Baatz assumed “Vorwerke” to larger villas that were managed by tenants.

- ^ Karl-Heinz Lenz: Rural settlement. In: Thomas Fischer (Ed.): The Roman Provinces. An introduction to their archeology . Theiss-Verlag, Stuttgart 2001, p. 67. On the colony as a whole: Klaus-Peter Johne : From the colony economy to the colony. A Roman relationship of dependency in the mirror of research , Berlin 1994 (public lectures at the Humboldt University in Berlin, issue 18) PDF .

- ↑ Ursula Heimberg: Villa Rustica. Living and working on Roman country estates . Darmstadt 2011, p. 13 .

- ↑ Vera Rupp and Heide Birley: The villa rustica - farm or magnificent country estate? In: Vera Rupp, Heide Birley (Hrsg.): Country life in Roman Germany. Theiss, Stuttgart 2012, ISBN 978-3-8062-2573-0 , p. 27.