Campona Castle

| Campona Castle | |

|---|---|

| Alternative name | Campona |

| limes | Pannonian Limes |

| section | 5 |

| Dating (occupancy) | End of 1st / early 2nd century to end of 4th / early 5th century |

| Type | Alenkastell / Reiterkastell |

| unit | a) Ala I Tungrorum Frontoniana b) Ala I Thracum veterana sagittaria ? Ala I Thracum victrix civium Romanorum ? c) Equites Dalmatae |

| size | 178 × 200 m |

| Construction | a) wood-earth b) stone |

| State of preservation | Remains of the building are visible above ground, the gate structures of the Porta principalis sinistra and the Porta praetoria have been preserved. |

| place | Nagytétény |

| Geographical location | 47 ° 23 '26.9 " N , 18 ° 59' 4.7" E |

| height | 102 m |

| Previous | Budapest-Albertfalva Castle (northeast) |

| Subsequently | Matrica Fort (southwest) |

The Campona fort was a Roman equestrian camp , the crew of which was responsible for security and surveillance tasks on the Pannonian Danube Limes ( Limes Pannonicus ) . The river formed here in large sections the Roman imperial border. The ground monument is located in today's Nagytétény ( German Großteting ), a formerly independent municipality on the south-western outskirts of the Hungarian capital Budapest ( 22nd district ). The finds from the fort testify to post-military use by the civilian population in the 5th century. The relatively rich occurrence of inscriptions , especially of tombstones and altars, also occupies a large part of the finds .

location

Since the Neolithic , there has been continuous settlement in the Nagytétény area. So could Alföld Linear Pottery of the Želiezovce group of Bükk culture , the Baden culture and other early groups are detected. During the excavation of a Roman tower of the defensive wall, a Neolithic stool grave was also found among the Roman cultural layers , the Sándor Gallus jun. first described in 1936. The late Celtic people of the Eraviski , who had their headquarters on the Gellértberg to the north, settled here until Roman times . So-called six - post houses ( pit houses ) of this culture have been observed from Nagytétény . In the 20th century, deposits of fuller's earth were mined in the Nagytétény plant of the Budapest Chemical Works . The Campona fort stood close to the banks of the Danube, around eight kilometers southwest of the nearest garrison site in Budapest-Albertfalva .

Research history

The garrison site, whose ancient name cannot be found in any of the traditional Roman sources, has never been completely forgotten because of the remains of buildings that were still standing - at least partially - even after a thousand years. The oldest report about the fort comes from the Viennese humanist and historian Wolfgang Lazius (1514–1565). He mentioned a mighty basilica , the remains of which could still be seen at that time, but incorrectly identified Campona as Potentiana . When Nagytétény Castle, which was expanded in its current form around 1766 (also known as Großteting Castle in literature), was erected on the rear of the building - due to the ancient structures that still partially define the corridor - exactly on the edge of the eastern defensive wall and therefore not covered the fort area. During the route of the railway line between Budapest and Fünfkirchen in the 19th century, a large number of stone monuments, some sarcophagi, the remains of a chariot burial and various other things came east of the fort - between the former fort ditches and the Danube bank - in the area of the vicus (camp village) Grave goods brought to light.

The first scientific excavations in the fort area began in 1935 under the direction of István Paulovics (1892–1952). The finds he had recovered from the camp and the surrounding vicus were unfortunately destroyed in the Second World War. An important result of his investigations was u. a. the unequivocal identification of the camp as the ancient Campona . This name could only be found in writing at the place where it was found. One generation of researchers later, Ferenc Fülep (1919–1986) succeeded Paulovics. Fülep worked in Campona between 1949 and 1952 and between 1954 and 1957 and concluded his field research in 1960 with an extensive excavation. A rescue excavation in 1995 was followed by another major excavation campaign in the fort area from July 1996, led by László Kocsis . Most of the fort is built over today. Only the area of the pre-camp, the so-called Praetentura , remained as a research and excavation area. The remains of the building located there, such as the stumps of a building directly at the intersection of Via praetoria and Via principalis as well as the foundations of the Porta principalis sinistra (east gate) and the Porta praetoria (south gate) were preserved and made accessible to the public.

Building history

Defensive wall, gates and towers

The early wood and earth fort was built by the Germanic Ala I Tungrorum Frontoniana, who was detached from Aquincum (Budapest), possibly during the last years of the reign of Emperor Domitian (81-96) on the Eravisker settlement area, which was then part of the Pannonia inferior province (Lower Pannonia) belonged, erected. Kocsis dated the building period in the early 2nd century.

The expansion of the fort in stone was made by those from Thrace originating Ala I Thracum veterana sagittariorum cives Romanorum . While many researchers estimate these modifications to be in the early days of the reign of Emperor Antoninus Pius (138–161), Kocsis sees the destruction of the fort during the Marcomann Wars (166–180) as the reason for the stone expansion.

The excavations by Paulovics and Fülep provided numerous evidence of the two construction phases. On the basis of these findings it soon became clear that the rectangular, 178 × 200 meter stone fort had been built directly over the planed remains of the wood-earth warehouse. The fortification had the typical floor plan for Roman military buildings of that time with rounded corners (playing card shape) and was surrounded by a double weir. In each of the four corners there was a trapezoidal tower that was erected at the same time as the defensive wall was built - but only after it was completed. The construction plan also provided for a gate on each of the long and broad sides, which was flanked by two 4 × 3.5 meter square towers. The praetorial front with the porta praetoria faced the enemy. In Campona these were the Sarmatian Jazygens who settled in Barbaricum on the opposite bank of the Danube . All four passages were designed with two lanes and separated from each other in the middle by a spina (separating wall). The Porta principalis sinistra measured a total of 21.1 × 5.3 meters.

In a later phase of renovation, the fort appears to have been equipped with two additional intermediate towers on each of its four flanks. For this purpose, the defensive wall was laid down in the desired tower width and then the intermediate tower protruding one wall width from the defense was installed. At the end of the 2nd or the beginning of the 3rd century, a semicircular tower was added in front of the two corner towers on the Praetorial Front. As Fülep was able to prove, identical specimens were also available on the northwest and northeast corner tower on the Dekuman front (back); these were almost completely demolished during the later construction of the mighty fan-shaped towers that followed.

The construction of these fan-shaped towers, which can be proven at many Danube fort sites, which made fan-shaped bastions out of all corner towers, happened in Campona possibly due to severe devastation, which, among other things, was caused by an attack by the Jazyans in this area during the reign of Constantine the Great (306-337) in the year 322 had been caused. However, the construction work could also date to the following years before the middle of the 4th century. A coin from the reign of Emperor Constantine II (337–340) recovered in connection with the same renovations at the Annamatia fort could provide the term post quem . Since the fan-shaped towers protruded far from the fort wall and into the area of the inner fort moat, it had to be filled in. It was replaced by a double moat a little further away. The bricks for the renovation work at that time were supplied by the Legio I Adiutrix (1st Legion "the helper") stationed in Aquincum .

The closure of the two gates on the long sides, the Porta principalis sinistra and the Porta principalis dextra , which were closed with a U-shaped front wall or a corresponding tower, dates from the same time or a little later . In 2005 , Péter Kovács found a total of 50 stamped bricks of the then high commander of the province, Terentius dux , in the rubble of the U-shaped walling at the Porta decumana in Baracspuszta , which shows a very specific chronological assignment of this construction project during the reign of Emperor Valentinian I (364-375 ) makes possible at least for this garrison location.

A renovation phase can actually be proven for Nagytétény during the reign of Emperor Valentinian I (364–375). However, this is possibly connected to an attack by the Quaden and Jazygen, which is connected with the emperor's politically completely flawed border policy and the insidious assassination of the Quad king Gabinius during a feast given by Marcellianus dux , then commander in chief of the Pannonian province of Valeria . The attackers were able to be repulsed by the Romans in 375, but the fighting resulted in widespread devastation of the Pannonian border region. As the archaeologist Endre Tóth noted, however, the late antique reconstructions of the Nagytétény fortifications cannot be related to a single historical local event, as the same and similar construction measures were carried out on many other Danube fortifications.

Interior development

Ferenc Fülep exposed smaller sections of the interior development, especially the Principia , the garrison's headquarters. Several construction phases could be identified, but many questions still remain unanswered. In the soil of the early post-Roman cultural layer on the Principia - from the end of the 4th century - the outlines of Sarmatian and Hunnic houses emerged next to a post pit . The remains of hearths were also found in situ in two houses .

The function of a stone building in front of the Principia on Via praetoria leading to the main gate has not yet been clarified. During his investigations, Kocsis was also able to determine that the Via praetoria from the Porta praetoria to the staff building was flanked on both sides by a representative, 7.70 meter wide colonnade .

Like many other forts on the Danube Limes, the fort probably changed into an oppidum towards the end of Roman rule . Various finds prove that the fort was still used by the civilian population in the 5th century.

Troop

The following garrison units are known for Campona :

| Time position | Troop name | |

| End of 1st / early 2nd century AD | Ala I Tungrorum Frontoniana | The 500-strong first Ala of the Tungerer , nicknamed Frontoniana , was initially stationed in the Asciburgium fort as a replacement for the Cohors Silaucensium during the Early Claudian period on the Lower Germanic Rhine Limes and can be traced back to 71 AD in Lower Germany. The Ala then came to Dalmatia, was subsequently relocated to Pannonia and built the auxiliary fort of Aquincum in 73 AD . Around the year 80 the unit was possibly in the Upper Pannonian provincial capital Carnuntum . The epigraphist Barnabás Lőrincz (1951–2012) assumed in 2001 that the Tungrians were stationed there until 1989. The troops took part in the Dacer Wars of Emperor Domitian (81-96) from 85 to 92 , and was relocated to Campona under Emperor Trajan to be moved to Intercisa in 105 . |

| from 138 AD | Ala I Thracum veterana sagittaria ? | The first archer ala of the Thracian veterans was relocated to the province of Upper Pannonia before the Parthian War of Trajan, possibly in 106, and most likely operated in the Carnuntum area during his reign . The Ala Nova Fort in today's Schwechat could be considered as their quarters there . Subsequently, the Thracian horsemen were barracked until 118/119 in the Intercisa (Dunaújváros) fort and, according to Lőrincz, were assigned to Campona from 138 onwards . The former director of the Roman Department of the Roman-Germanic Central Museum , Barbara Pferdehirt , however, rejected these assumptions, as no Ala of this name was known from the two Pannonia of the Principate's time. On the other hand, she suggests using the Ala I Thracum Victrix , which is well documented for Upper Pannonia, in this context . An Ala I Thracum veterana or Ala I Thracum is named on an inscription from Nagytétény that was created between 198 and 222. From there the honorary name Antoniniana has been passed down, which the unit temporarily led. |

| 4th century | Equites Dalmatae | This unit of Dalmatian horsemen stationed in Campona in late antiquity is only known from the Notitia Dignitatum . She appears there on the list of troops of the Dux provinciae Valeriae . |

Vicus and burial ground

Paulovics uncovered a Mithra temple in the area of the camp village during his excavations in the second half of the 1930s . A grave field from the 3rd and 4th centuries could be located east of the fort.

Post-Roman development

In Campona , in the turbulent decades before the final evacuation of the Pannonian provinces by the Roman troops in 433, Hunnic traces can also be found. From the 6th century Avars settled in the area around the Roman ruins, which the Slavs followed shortly afterwards .

Important finds

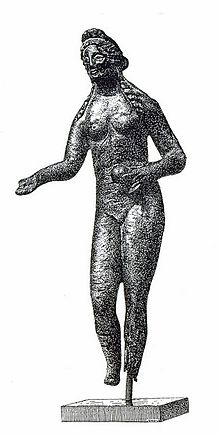

Venus of Campona

In 1953 Fülep came across a 18.3 centimeter high statuette of the goddess of love Venus while examining a room that was perpendicular to the Via principalis . The figurine, apparently made in a Pannonian artist's workshop, bore the portrait-like features of the Emperor's wife Faustina (?) And lay in the rubble of a layer of destruction that could be dated to the reign of Emperor Mark Aurel (161-180). It probably dates from the time of the Marcomannic Wars.

Coin hoard

Even before the first scientific excavations began , a hoard of around 10,000 small bronze coins from the 4th century was discovered in 1887 on Zsákstrasse, which runs parallel between the former western defensive wall and Via praetoria . In Hungarian research circles it is assumed that this is the troop coffers of the fort garrison. On numerous copies, among other things, varying images of a fortified camp gate are embossed, they also bear the legend Providentiae Augg or Caess and all date from the reign of Emperor Constantine the Great (324–337). Coin issues, which also name his son and successor Constans , are missing, however; they were first issued in December 333, in the course of his appointment as Caesar . Presumably the troop coffers were hidden before this event. The chronological assignment of the hoard is probably related to a historically documented invasion of the Sarmatians in 333. It is now in the Hungarian National Museum in Budapest.

Stone monuments

The stone monuments, especially those with inscriptions, take up a large part of the collection of finds. From them various social, societal, military-historical and ethnic points of view can be derived, which shaped life in the Roman Campona for many generations.

milestone

A milestone from Nagytétény from 229 indicates a distance to Aquincum of 14 (or nine?) Roman miles:

Imp (erator) Caes (ar)

M (arcus) Aur (elius) [Sev] erus

Alex [other P (ius) F (elix)]

Aug (ustus) po [nt (ifex)] max (imus)

trib (unicia ) pot (estate) VIIII

co (n) s (ul) III p (ater) p (atriae)

restituit

ab Aq (uinco)

m (ilia) p (assuum) XIV

Translation: "The Emperor Caesar Marcus Aurelius Severus Alexander , the pious and happy Augustus, supreme priest, holder of tribunician power for the ninth time , consul three times, father of the fatherland, [has restored this road], 14 miles from Aquincum"

Lost property

The finds from the excavations are now in the Hungarian National Museum in Budapest. The stone monuments, including the inscriptions, sarcophagi and miter reliefs, can be viewed in the lapidary of the Nagytétény Castle Museum (Nagytétényi Kastélymúzeum) in the baroque castle near the castle.

Limes course between Fort Campona to Fort Matrica

| route | Name / place | Description / condition |

|---|---|---|

| 5 | Érd-Ófalu (Burgus Campona 1) | At the southern end of Érd-Ófalu, the terrain rises to a plateau. In an area towards the end of the ascent, you can look further north and east. The road, which was not developed even at the beginning of the 21st century, runs in a south-west-north-east direction. In this area it leads through a cut flanked by two heights up to the plateau. At its ascent, the route is now called the “Roman Road”. It is most likely congruent with the ancient Limes road. The strategic advantage of this location was probably used by the Romans. One of the pioneers of Hungarian archeology, Janos Erdy, (1796–1881) was the first to suggest that there be a watchtower here on the northeast side of the road. However , so far no evidence of an archaeological site has been found either on aerial photographs or during field inspections . Shortly after Campona 1, the Limes Road split into two branches that initially ran almost parallel to each other. The western branch north of Dunafüred ran much more strongly in a south-westerly direction than the better preserved southern route. |

| 5 | Szazhalombatta, Fehérkereszti út - White Cross Street (Burgus Campona 2) | An aerial photo from 1955 in the border area of the Szazhalombatta municipality is very informative for archaeological prospecting. A first possible watchtower that can be identified on it is shown by weak soil discoloration on the west side of the eastern Limes road. Its recognizable moat delimits an area of around 38 × 38 meters and is around five meters wide. In the center of this fence there is a dark discoloration, which is typical for the location of the actual watchtower in aerial photographs. A lighter, 54 × 54 meter structure outside the mentioned trench area could refer to another trench. |

| 5 | Burgus Campona 3 Külső újföldek-corridor (= outer new territory corridor) | According to the aerial photo from 1955, another watchtower could have been located around 520 meters south of Campona 2. He too would have stood on the west side of the Limesstrasse. Here, the presumed trench covers an area of around 32 meters. Another, external structure with a size of 48 × 48 meters could represent another ditch, as in the case of Campona 2. |

| 5 | Burgus Campona 4 Hosszü hallway (= long hallway) | The Burgus Campona 4 is the third possible tower that the aerial photo taken in 1955 shows. His traces can be found around 1,100 meters south of Campona 3. The anomalies are based on an east-running dirt road, which presumably coincides with the ancient Limes road. It shows a quadrangular double ditch, the outer one being around 48 × 48 meters on the outside and the inner one being around 30 × 30 meters. A dark discoloration in the center of the enclosing trenches could mark the location of the actual watchtower. |

| 5 | Dunafured | The fort was located on an area south of Dunafüred that was heavily swamped in ancient times. |

Monument protection

The monuments of Hungary are protected under the Act No. LXIV of 2001 by being entered in the register of monuments. The Roman sites in Nagytétény and the surrounding area belong to the nationally valuable cultural property as archaeological sites according to § 3.1. According to § 2.1, all finds are state property, regardless of where they are found. Violations of the export regulations are considered a criminal offense or a crime and are punished with imprisonment for up to three years.

See also

literature

- Jenő Fitz (Ed.): The Roman Limes in Hungary (= Bulletin du musée roi Saint Etienne. Series A, Volume 22). Fejér Megyei Múzeumok Igazgatósága, Székesfehérvár 1976.

- Ferenc Fülep : Campona. In: Paulys Realencyclopadie der classischen Antiquity Science (RE). Supplementary volume XI, Stuttgart 1968, Sp. 357-368.

- Ferenc Fülep: Nagytétény. Rózsa Ferenc tér - MÁV vasútvonal között. A nagytétényi római tábor maradványai. In: Frigyes Pogány (ed.): Budapest műemlékei II, (Magyarország Műemléki topográfiája 7), Akadémiai Kiadó, Budapest 1962, pp. 643–652.

- Ferenc Fülep, Èva Cserey: Nagytétény műemlékei (The monuments of Großteting). Képzőművészeti Alap, Budapest 1957.

- Ferenc Fülep: Les fouilles du camp romain de Nagytétény (The excavations at Nagytétény Castle). In: László Vértes (ed.): Program et discours des chercheurs hongrois à la Conference Archéologique de la Académie Hongroise des Sciences. Budapest 1955, pp. 213-221.

- István Vörös: Nagytétény római tábor állatcsontmaradványai (Animal remains from the roman castellum at Campona-Nagytétény) . In: Folia Archaeologica , 40, 1989, pp. 75-101.

- Ákos Kiss: XVII. Nagytétény (Campona) . In: Pannonian architectural elements and ornamentation in Hungary. Akadémiai Kiadó, Budapest 1987. ISBN 9630541483 . P. 49.

- László Kocsis: Restart of the research in the Roman castle of Campona in Nagytétény-Budapest, district XXII. (Preliminary report), (Resumption of excavations at the Roman Campona Fort in Nagytétény-Budapest, XXII. District (preliminary report)). In: Specimina nova 16, 2002, pp. 183-198.

- Zsolt Visy: The Pannonian Limes in Hungary . Theiss, Stuttgart 1988, ISBN 3806204888 .

Web links

Remarks

- ↑ a b c d Jan Filip u. a .: Encyclopedic manual on the prehistory and early history of Europe . Volume 1, Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 1966, p. 199.

- ^ Edit Thomas, László Vértes: Archaeological finds in Hungary . Corvina, Budapest 1956, p. 56.

- ^ Sándor Gallus junior: A nagytétényi nepolitus sír (The grave of Nagyteteny). In Archeológiai Értesítő . Vol. 49, Budapest 1936, pp. 85-88.

- ^ Katalin Ottományi : The late Latène-Roman settlement of Budaörs. In: Acta archaeologica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae. Volume 55, No. 1–3, Akadémiai Kiadó, Budapest 2005, pp. 67–132, here: p. 85.

- ↑ Kastell Budapest Albertfalva at 47 ° 26 '21.18 " N , 19 ° 2' 48.4" O .

- ^ Zsolt Visy : The Pannonian Limes in Hungary . Theiss, Stuttgart 1988, ISBN 3806204888 , p. 89.

- ^ Zsolt Visy: The Pannonian Limes in Hungary . Theiss, Stuttgart 1988, ISBN 3806204888 , pp. 89-90.

- ^ László Kocsis: Campona Castellum. In: Zsolt Visy (ed.): The Roman army in Pannonia. Teleki Lázló Foundation 2003, ISBN 963-86388-2-6 , p. 106.

- ↑ a b László Kocsis: Campona Castellum. In: Zsolt Visy (ed.): The Roman army in Pannonia. Teleki Lázló Foundation 2003, ISBN 963-86388-2-6 , p. 107.

- ↑ CIL 3, 3400 .

- ↑ a b c d e f g Zsolt Visy: The Pannonian Limes in Hungary . Konrad Theiss Verlag, Stuttgart 1988, ISBN 3806204888 , p. 90.

- ↑ a b c d e László Kocsis: Campona Castellum. In: Zsolt Visy (ed.): The Roman army in Pannonia. Teleki Lázló Foundation 2003, ISBN 963-86388-2-6 , p. 108.

- ↑ a b Ference Fülep in: Archaeologiai értesítő 84. Akadémiai Kiadó, Budapest 1957

- ↑ a b Endre Tóth : The late Roman military architecture in Transdanubia . In Archaeologiai Értesitő 134, Budapest 2009, p. 33; Adolf Lippold (ed. By Gerhard H. Waldherr): The Historia Augusta. Steiner, Stuttgart 1998, ISBN 3-515-07272-1 , p. 377.

- ↑ Endre Tóth: The late Roman military architecture in Transdanubia . In Archaeologiai Értesitő . 134, Budapest 2009, p. 38.

- ^ Péter Kovács : Annamatia Castellum. In: Zsolt Visy (ed.): The Roman army in Pannonia. Teleki Lázló Foundation 2003, ISBN 963-86388-2-6 , p. 120.

- ↑ Endre Tóth : The late Roman military architecture in Transdanubia. Archaeologiai Értesitő 134. Budapest 2009. p. 52.

- ↑ Endre Tóth : The late Roman military architecture in Transdanubia. Archaeologiai Értesitő 134. Budapest 2009. p. 38.

- ^ Tilmann Bechert: The Romans in Asciburgium. Braun, Duisburg 1989, ISBN 3-87096-047-7 , p. 61f. ( Duisburg research , vol. 36)

- ↑ CIL 03, 09735 .

- ↑ AE 1993, +01307 .

- ^ A b Manfred Kandler: The auxiliary fort Carnuntum. Austrian Archaeological Institute, Vienna 1997. P. 73 (Austrian Archaeological Institute, special publications, volume 29).

- ↑ Barnabás Lőrincz: The Roman auxiliaries in Pannonia during the Principate's time. Part I: The Inscriptions. Forschungsgesellschaft Wiener Stadtarchäologie, Vienna 2001, ISBN 3902086025 , p. 86.

- ↑ Barnabás Lőrincz: The Roman auxiliaries in Pannonia during the Principate's time. Part I: The Inscriptions. Research Society of Vienna City Archeology. Vienna 2001, ISBN 3-902086-02-5 , p. 26.

- ↑ Barnabás Lőrincz: The Roman auxiliaries in Pannonia during the Principate's time. Part I: The Inscriptions. Forschungsgesellschaft Wiener Stadtarchäologie, Vienna 2001, ISBN 3902086025 , p. 24.

- ↑ Barnabás Lőrincz: The Roman auxiliaries in Pannonia during the Principate's time. Part I: The Inscriptions. Forschungsgesellschaft Wiener Stadtarchäologie, Vienna 2001, ISBN 3902086025 , p. 50.

- ↑ Barbara Pferdehirt: Roman military diplomas and dismissal certificates in the collection of the Römisch-Germanisches Zentralmuseum . Mainz 2004, ISBN 3884670867 , p. 94.

- ↑ CIL 3, 3391 .

- ^ Zsolt Mráv in: Péter Kovács , Ádám Szabó (eds.): Tituli Aquincenses. Volume 2: Tituli Sepulcrales et alii Budapestini reperti . Pytheas, Budapest 2010, ISBN 978-963-9746-73-2 , no.1001.

- ↑ Ádám Szabó in: Péter Kovács, Ádám Szabó (eds.): Tituli Aquincenses. Volume 2: Tituli Sepulcrales et alii Budapestini reperti. Pytheas, Budapest 2010, ISBN 978-963-9746-73-2 , no.1004.

- ↑ CIL 3, 3391 .

- ↑ ND occ. XXXIII, 12

- ^ Edith B. Thomas, László Vértes: Archaeological finds in Hungary . Corvina, Budapest 1956, p. 210.

- ↑ Zsákstraße at 47 ° 23 '26.09 " N , 18 ° 59' 1.73" O

- ↑ a b László Kocsis: Campona Castellum. In: Zsolt Visy (ed.): The Roman army in Pannonia. Teleki Lázló Foundation 2003, ISBN 963-86388-2-6 , pp. 106-107.

- ^ Maria Radnoti-Alföldi : Gloria Romanorum. Writings on late antiquity . Steiner. Stuttgart 2001, ISBN 3-515-07918-1 , p. 154.

- ↑ Klára Kuzmová , Ján Rajtár : Previous findings on the fortification of the Roman fort in Iža. In: Slovenská Archeológia . Vol. 34, 1986, pp. 185-222, here p. 208.

- ↑ CIL 3, 3719 (with the indication of 9 miles, MP VIIII ); Data sheet at ubi-erat-lupa; Retrieved June 7, 2014.

- ↑ Route = numbering follows Zsolt Visy: The Pannonian Limes in Hungary (Theiss 1988) and Zsolt Visy: The ripa Pannonica in Hungary. (Akadémiai Kiadó 2003).

- ↑ Burgus CAMPONA 1 at 47 ° 21 '16.91 " N , 18 ° 55' 58.58" O .

- ↑ Limesstrasse at 47 ° 21 '38.54 " N , 18 ° 56' 18.27" E ; Roman Road at 47 ° 21 ′ 20.25 " N , 18 ° 56 ′ 3.93" E ; western Limes Road at 47 ° 20 ′ 21.45 " N , 18 ° 55 ′ 25.44" E ; western Limes Road at 47 ° 19 ′ 56.44 " N , 18 ° 55 ′ 14.31" E

- ↑ a b Zsolt Visy: The ripa Pannonica in Hungary. Akadémiai Kiadó, Budapest 2003, ISBN 963-05-7980-4 , p. 65.

- ↑ Western Limesstraße at 47 ° 20 '59.03 " N , 18 ° 55' 37.78" O ; western Limes Road at 47 ° 20 ′ 21.45 " N , 18 ° 55 ′ 25.44" E ; western Limes Road at 47 ° 19 ′ 56.44 " N , 18 ° 55 ′ 14.31" E

- ^ Zsolt Visy: The ripa Pannonica in Hungary. Akadémiai Kiadó, Budapest 2003, ISBN 963-05-7980-4 , plate 16. The area of Százhalombatta.

- ↑ Burgus CAMPONA 2 at 47 ° 20 '49.08 " N , 18 ° 55' 47.21" O .

- ↑ Eastern Limes Road at 47 ° 21 ′ 0.09 ″ N , 18 ° 55 ′ 50.82 ″ E ; eastern Limes Road at 47 ° 20 ′ 13.5 " N , 18 ° 55 ′ 39.57" E ; eastern Limesstraße at 47 ° 19 '32.15 " N , 18 ° 55' 28.03" O

- ↑ a b c Zsolt Visy: The ripa Pannonica in Hungary. Akadémiai Kiadó, Budapest 2003, ISBN 963-05-7980-4 , p. 66.

- ↑ Burgus CAMPONA 3 at 47 ° 20 '30.27 " N , 18 ° 55' 42.54" O .

- ↑ Burgus CAMPONA 4 at 47 ° 19 '54.52 " N , 18 ° 55' 32.71" O .

- ↑ Kastell Matrica at 47 ° 18 '2.28 " N , 18 ° 55' 4.78" O .