Batavian Uprising

| date | 69 to 70 |

|---|---|

| place | Germania inferior and Gaul |

| output | Uprising was put down |

| Parties to the conflict | |

|---|---|

|

Bataver |

|

| Commander | |

|

Marcus Hordeonius Flaccus

|

|

The Batavian Rebellion was a revolt of the Germanic Batavians , other Germanic ( Tenker , Cugerner , Brukterer, etc.) and Celtic tribes from August of 69 against the Roman rule in Lower Germany . The survey lasted almost a year.

After the initial successes of the Batavians under their auxiliary troop leader Iulius Civilis , who defected from the Romans , the uprising was suppressed by Quintus Petilius Cerialis until the autumn of 70. The decisive battle at Xanten in July 1970 lasted two days. The Batavian Rebellion is described in detail in Tacitus . However, as with most ancient authors, the objective description of what happened is not always in the foreground. The Germanic tribes were characterized as barbaric forest dwellers, although they lived mainly from agriculture.

The Batavian uprising was also very closely linked to Roman politics. In the course of the uprising, several other tribes that had previously been under Roman rule joined the revolt, including the Treveri and Lingons in particular . Sometimes they acted as immediate allies of the Batavians, sometimes these uprisings were independent, but had an indirect effect on what happened.

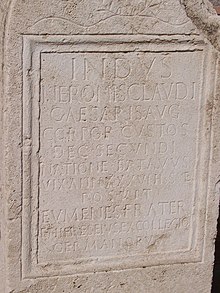

Iulius Civilis

Iulius Civilis (later the initiator and main leader of the so-called Batavian Rebellion ) came from a noble family of the Germanic Batavians on the northwestern Lower Rhine in the area of today's Betuwe in the Netherlands. The tribe initially lived in friendship with the Romans. Early on, Civilis came into Roman service as the leader of Batavian auxiliaries, as did his brother Claudius Paulus , as well as a nephew by the name of Julius Briganticus (who, however, took a Rome-friendly opposing position to Civilis in the uprising).

Civilis had lost an eye and, according to Tacitus, acted or acted like the legendary Hannibal . He was married and had a young son - he transferred his wife and son as hostages to Cologne, the city of the Ubier, during the Batavian War .

During the reign of Emperor Nero (54-68 AD), Civilis and his brother Claudius Paulus fell out of favor: the brother was executed by the Roman general Fonteius Capito , Civilis was brought to Nero in chains in Rome. However, Nero was urged to commit suicide by his adversary Galba , Galba himself became emperor and pardoned civilis.

Galba was the first of three other emperors in the four-emperor year , followed by Otho , who was murdered after a short reign and who was followed by the Lower Germanic military leader Vitellius as - temporary - emperor. Civilis returned to Germania in Roman services, but was again accused of treason under Vitellius, but was able to flee. These events made him strongly dislike Vitellius and so he secretly and initially supported the candidacy of the later emperor Vespasian , as whose "friend" he called himself.

In 69, while Vitellius was fighting against Otho and later against Vespasian for his empire, Civilis used the ongoing unrest in Italy to raise the Germanic tribes on the Rhine under the leadership of the Batavians and with the support of Germanic tribes on the right bank of the Rhine under the seer Veleda . At times he was able to involve Gallic tribal leaders in the fight against Rome.

Prehistory: The end of Nero in the year 68

In order to understand the uprising of the hitherto loyal allies of Rome, one must look at the history of the years 68 and 69. In April 68, Servius Sulpicius Galba attempted from Spain to overthrow Emperor Nero . He made a secret agreement with Gaius Julius Vindex, who was governor in Aquitania (today's Bordeaux region) at the time. Vindex tried to convince the governor in Upper Germany, Virginius Rufus, of a revolt against Nero. However, when the troops of the Vindex returned to the Gallic troops of Rufus, they thought it was an attack. Without orders from Rufus, the Gallic troops defeated the troops of Vindex. The circumstances of the battle cannot be exactly reconstructed due to the sources. Galba, who dared to flee forwards after the defeat and suicide of Vindex, renounced his loyalty to Nero by demonstratively calling himself legatus senatus et populi Romani (plenipotentiary of the Senate and the Roman people). The Gallic troops, who had behaved loyally to Nero, demanded a donative from him , which Nero refused. Under pressure from the usurper Galba, Nero committed suicide in June 68. Galba was promoted to emperor and recognized by the Senate in the hope that it would be the better choice. Galba pardoned the imprisoned Batav leader Civilis. The legions from Germania now found themselves in a difficult position. After they had behaved loyally to Emperor Nero, they were now considered enemies of the new Emperor Galba.

January 69: The end of Galba

On January 1, 69, the Mainz troops were to take their oath of allegiance to the new Emperor Galba. Due to the previous events, the members of the two legions stationed in Mogontiacum (today's Mainz ) tore the images of Galba from their standard and instead swore their oath of allegiance - similar to Galba himself nine months earlier - only to the Senate and the Roman people. The next day, the Bonn Legion proclaimed Aulus Vitellius , the recently appointed governor Vitellius of Lower Germany , as the anti-emperor. The governor of Upper Germany had proven to be weak, which is why they chose Vitellius. The Lower Rhine Legions joined the election of the Upper Rhine Legions. Vitellius usurpation was thus directed against Galba, who did not meet the expectations placed on him in Rome. His troops in particular were dissatisfied, as Galba refused all donations. The 70-year-old Galba fought desperately for power, but was murdered by the Praetorian Guard just a few days later, on January 15th . Instead, they elevated - temporarily - the 36-year-old non-military Marcus Salvius Otho , who had initiated the assassination of Galba, to emperor. The Senate only grudgingly recognized him. However, since Vitellius had now been made emperor by his army, there was no turning back.

January to July 69

Vitellius reacted immediately. He sent around 65,000 soldiers from the Rhine Army to Italy in two columns of march. The larger group moved through eastern Gaul and the Cottian Alps , the smaller part under Aulus Caecina Alienus on the direct route up the Rhine through Helvetia. After fierce battles against the Helvetii, whom Vitellius refused to follow and held to (the already dead) Galba, Caecina crossed the Great St. Bernard with 22,000 men at the latest in early April 69 and reached the Po Valley.

This troop contributed decisively to the victory of the Vitellius faithful over Otho in the Battle of Bedriacum near Cremona on April 14, 69, Otho committed suicide the morning after. Vitellius, the new sole ruler, found out about this a few days after leaving Cologne for Italy. After stripping most of the Rhine frontier from troops in January , he now sent back the bulk of his troops, including eight Batavian auxiliary cohorts , one of them under Iulius Civilis, who came under suspicion again under Vitellius but was able to withdraw.

July / August 69: Vespasian claims the throne, Batavian revolt

But hardly were these cohorts back in Mainz when they were summoned to Italy again , because Titus Flavius Vespasian has now claimed the throne. The qualified commander and governor had himself proclaimed emperor in Alexandria on July 1st and was now advancing with his legions from Judea . Vitellius, who had arrived in Rome in mid-July, had requested further troops from the Rhine border, but the local commander, Marcus Hordeonius Flaccus , refused to send them . Thereupon more troops were to be raised under the Batavians , which in August 69 triggered the actual uprising of the Batavians . For them it was no longer about the rule of this or that Roman emperor, but about the end of Roman rule over their people.

Civilis was now in command of one of the auxiliary cohorts on the march back. The situation was difficult for the Roman commanders in Germania. The civil war raged in Italy with an uncertain outcome. Most of the troops in Germania tended towards Vitellius. Shortly before, in the east of the empire, in the provinces of Aegyptus , Syria and Iudaea, as well as in the Danube regions, Titus Flavius Vespasianus had been proclaimed emperor against Vitellius; his troops had marched towards Rome.

Tacitus reports that the troops of Vitellius and the troops loyal to Vespasian watched each other in late summer and autumn 69 in a kind of trench warfare. The arrival of Vespasian in northern Italy finally brought the decision.

Before his ride to Rome, Vitellius had in the tribal areas of the Batavians and Cananefats carried out what they perceived to be arbitrary levies in order to strengthen his associations for the conflict with Vespasian. Civilis took this as a reason to rise up against Vitellius together with Cananefaten and Friesen , whereby he at first cleverly gave the impression of intervening on the side of Vespasian against Vitellius. In this context, a letter from Antonius Primus to Civilis is often cited, which should have reached its addressee in the late summer of 69 and in which the Batavians were asked to intervene in the war on Vespasian's side. A punitive expedition by the (Vitellian) Romans ended in disaster, because during the battle the Batavian auxiliary riders changed sides and the ubian and Treverian auxiliary associations fled. The remains of the expeditionary force were only able to save themselves to Vetera with great difficulty .

During the entire Batavian uprising, this "Fort Vetera" held a key position (more precisely, the Fort Vetera I ). It was on the Rhine (near today's Xanten ) in the area of the Germanic Cugernians, who had also joined the Batavian revolt.

The uprising gained momentum when, in late summer / early autumn 69, the eight Batavian cohorts stationed in Mogontiacum marched north and joined forces with the Civilis. Civilis swore them in on Vespasian and now also called on the parts of the 5th and 15th Legion remaining in Vetera to join the Flavier cause . However, the Vetera garrison remained loyal to Vitellius. Walls and ramparts of the camp were strengthened, but sufficient provisions were not provided to withstand a prolonged siege.

After a first, rejected attack attempt, the civilis' troops, who meanwhile ruled the entire area on the left and right of the Rhine, as well as the Rhine river itself by means of their fleet captured by the Romans, consequently decided to starve the camp. A relief army of soldiers from the Legio XXII Primigenia under the command of Gaius Dillius Vocula was set on the march from the south, united in Novaesium with the Legio XVI Gallica , but did not dare to penetrate further into the area around Vetera , but struck Gelduba near the Ubier village a camp.

Tacitus describes in detail (Historien Book IV, 26.27 ff.) The events at Gelduba (today Krefeld-Gellep) which developed into a battle that was costly for the Romans. The former military camp at the border village of the Ubier , a little southwest of the location of the later fort, was fought over in autumn 69.

The fighting began after the Commander-in-Chief Gaius Dillius Vocula with 8,000 to 12,000 legionaries and auxiliary troops on the way from Neuss to Vetera (Xanten) near the Ubian border village of Gelduba pitched a large marching camp with trenches, entrenchments and gates. At this point in time, the Germanic Ubians were still supporting the Romans, while the Cugernians on the other side of the Gelfbach, like the Germanic tribes across the Rhine, had already sided with the Batav leader Iulius Civilis. Vocula was on a brief raid with a cavalry squadron in the Cugerner area when Teutons on the right bank of the Rhine - all good swimmers - captured a Roman supply ship in front of the port of Gelduba. Houses in the civil town of Gelduba were also set on fire. The legionaries blamed the camp commandant Herennius Gallus for the loss of the ship because of his hesitant behavior, beat him and imprisoned him. Only the returning Vocula could free him and punish the rioters.

Meanwhile, the Army of the Civilis increased incessantly with influx from almost all regions of Germania and began to devastate the areas of the Morin , Menapier , Ubier and Treverer, i.e. the entire Rhineland down to the Moselle and across to the North Sea coast. The siege ring around Vetera was further strengthened, and the attempted assault resumed. Only a failure of the crew provided a little relief and ended the attempts at conquest. However, a promising outbreak was out of the question.

A short time later the Batavians first appeared in front of Asciburgium , then again in front of Gelduba and attacked the marching camp on a broad front. Batavian horsemen attacked from the northwest, while the Batavian infantry walked around the camp and charged from the south. Escaping Roman horsemen were repulsed, the Batavians not only penetrated into the outer auxiliary troop camp, but also into the headquarters of the legion camp. The Romans hardly had time to align their catapults and cock the projectile machines. The camp gates were particularly fought over.

Tacitus writes about this (Historien, Book IV):

- "... the result was not a battle, but a slaughter. The Nervian cohorts bared our flanks out of fear or faithlessness; thus one met the legions that lost their standards and were thrown down within the wall."

Nevertheless, this time the tide turned in favor of the Romans: Riding auxiliary troops of the Vascones (Basques), who had been raised by the brief emperor Galba and sent to the Rhine, approached the marching camp from Neuss and rushed into battle with shouting . From behind they penetrated the Batavian infantry and killed most of them. The Batavians believed that they were legions from Mainz and so the Batavian horsemen turned to flee with high losses. Although the Roman side had many casualties to mourn, this time the marching camp was not taken and only later fell into the hands of the Batavians (after the Ubians and some Gallic tribes also supported the Batavian rebellion). After the Batavian Uprising ended, the Gelduba marching camp was torn down in AD 71 and the construction of the first (actual) fort began.

Late 69: Vespasian wins in Italy, uprising in the north

Vespasian chose Verona as his base of operations , as he expected an attack by troops loyal to Vitellius from Germania. From there the Flavians won on 24/25. October in the Second Battle of Bedriacum near Cremona . The assassination of Vitellius on December 20, 69 in Rome brought the decision. He had been chased from the imperial office under the leadership of Marcus Antonius Primus , was presented in public, dragged through Rome on a hook and thrown dead into the Tiber.

The news of this, as well as Vespasian's request to Civilis to end the fighting activities, should have arrived on the Lower Rhine in December of that year. However, it was ignored by the Batavian, who instead sent part of his troops against Vocula and continued the siege of Veteras . Vocula defeated the troops sent against him and marched on Vetera for relief . There the battle raged back and forth until a failure of the castle garrison decided it in favor of the Romans. Vetera was released from the enclosure, but the supply situation remained precarious, the rebels still dominated the surrounding area and Vocula failed to pursue the defeated forces of Civilis.

Just at a point in time when Vocula had withdrawn another 1,000 men from the Vetera garrison to be used to secure supplies, Civilis closed the camp again at the end of December 69. Vocula withdrew to Novaesium and was pursued by Civilis, who finally took the long-contested Gelduba and whose cavalry advanced to Novaesium . In the following months, the main events of the war shifted deeper into the south of the Rhineland, where some Gallic tribes rose and the Ubians had joined the uprising (though only temporarily).

The Gallic Treverians under their leaders Iulius Classicus and Iulius Tutor had meanwhile risen against Rome, as had the Gallic Lingons under their leader Iulius Sabinus (who, however, as a counterpart to the Bataver Civilis, was striving for his own Gallic empire and cheered himself for a few days as a counter-emperor let).

Legal Rheinische Germans took advantage of the opportunity, meanwhile, to looting and raids in the southern uprising area in particular the chat and Usipetes .

In the meantime, the situation on the Lower Rhine has come to a head; the occupation of the legionary camp Vetera surrendered now that the supplies were exhausted. After the withdrawal from the fortress - promised by Civilis with safe conduct - Germanic tribes on the right bank of the Rhine ( Brukterer , Tenkerer ) lay in wait for the defeated Romans and killed a large number of the legionaries without Civilis being able to prevent this. The rest fled back to the castle, which was set on fire by the besiegers. Those who did not succeed in breaking out died in the flames. The destroyed Fort Vetera was rebuilt at a somewhat distant place after the end of the uprising.

The year 70: the suppression of the uprising

After Vespasian's victory in Italy at the end of October, enough troops were finally available to put down the Batavian uprising. They were run by Quintus Petilius Cerialis , a confidante and probably Vespasian's son-in-law. Petilius Cerialis had already gained military experience in Britain during the suppression of the Boudicca uprising and had supported Vespasian in the fighting in Italy.

Vespasian deployed an enormous force made up of the following legions: Legio VIII Augusta , Legio XI Claudia , Legio XIII Gemina , Legio XXI Rapax and the newly raised Legio II Adiutrix . These legions had to cross the Alps, in addition the Legio XIV Gemina from Britain and the Legio VI Victrix and Legio I Adiutrix from Spain were put on the march. Then there were the remaining legions of the Rhine Army. If one considers that the uprising in Judea , which led to the destruction of Jerusalem in the year 70, was not yet completely suppressed and the entire Roman army comprised around 30 legions, one can assess the importance of the Batavian uprising for Vespasian.

Not all of the legions sent to Germania were used in combat; some secured the hinterland and the supply routes and thus prevented the uprising from spreading to other Gallic or Germanic tribes.

With the appearance of the Roman general Quintus Petilius Cerialis and his legions, the period of defeat for the rebels began. A contingent of the lingon Sabinus was defeated, Sabinus himself escaped and went into hiding.

Despite the support of the Brukterer and Tenkerer on the right bank of the Rhine , the Batavians lost more battles in the year 70, for example at Bingen ( Bingium ), Riol ( Rigodulum ) and Trier ( Augusta Treverorum ).

An important decisive battle near the destroyed Fort Vetera near Xanten (in July 70) was lost: despite a dam breach initiated by Civilis with extensive flooding of the Rhine, the Romans were able to hold their own in the shallow and marshy terrain (after a deserter found a place for Reiter had betrayed usable ford). Due to heavy rainfall, however, no decision was made.

The fighting now shifted northwards towards Kalkar and Kleve . Cerialis received reinforcements from a legion from Spain, and the Batavians received help from the Chauken tribe . Civilis had the old Drusus dam pierced near Kleve to fend off the Romans with floods. Meanwhile, the Gallic allies of the Civilis, Classicus and Tutor, tried to recruit supporters from the tribes on the other side of the Rhine.

The fighting spread in the following days to the northwest towards Nijmegen and Bataver Island. Quintus Cerealis pursued the Batavians with his legions. Ultimately, the fighting was on four fronts simultaneously: Civilis and his allies split up and besieged the forts and Roman camps at Arenacium (cattle, near Kleve), Batavodurum (Nijmegen) and Grinnes and Vada (in Gelderland) at the same time . The Batavians suffered heavy losses. The Batav leader finally escaped in battle under difficult circumstances: after falling from his horse, he had to swim to the other bank. Classicus and Tutor fled in waiting boats. However, the Romans missed the victory because they had too few sailing boats available.

There was a short break in the fight during which Cerialis inspected the winter quarters in Neuss. On the way back, Richtig Kleve, his ships were attacked by Teutons. The Roman general himself escaped capture only because he was not on his command ship, but on another ship having a shepherd's hour with an Ubier woman. His command ship was hijacked and dragged up the lip to the Germanic seer Veleda as booty . Other Roman ships fell into the hands of the civilis' troops.

In the Waal / Maas unification area, the ship fleets watched each other, but there was no decisive battle. Nevertheless, the Romans had advantages and devastated parts of the Bataver Island. Civilis and his allies withdrew to the other side of the river.

In the meantime, the peoples involved in the fighting were disenchanted with the war, and the Batavians were no longer fully behind their leaders. The Gallic Treveri and Lingons had already given up the fight and were again under the sovereignty of Rome. The Ubier of Cologne also switched fronts, yes, they had even lured previous Germanic allies into an ambush. Many Germanic tribes across the Rhine withdrew to their side of the Rhine.

The Rhine had swelled dangerously due to heavy rains, and the camps of the fighting were endangered by flooding. All sides were tired of the battle. The Roman military leader sent secret messages to the Batavian and Germanic peoples, including the seer Veleda, in which he offered peace and safe conduct and warned against "... now homeless civilis to give refuge." Vespasian is now the new emperor in Rome and That was the goal that the rebels had originally pursued. Why keep fighting now.

The civilian in hiding also saw the change in mood and saw surrender as the last resort. That was at the end of the year 70. The (incompletely preserved) histories of Tacitus finally describe the “surrender speech” of Civilis (in which he referred to his earlier friendship with Vespasian) at the demolished bridge of the river Nabalia (IJssel?), Near the Splitting of the Rhine into Waal and Nederrijn . This is where the histories of Tacitus end.

Nothing is known about the further life of the civilis. The Batavians were gradually Romanized and were absorbed into the expanding Salfranken 250 years later .

Consequences of the uprising

After the turmoil of the four-emperor year , the finances of the empire were badly shattered. Vespasian's prudent restructuring policy, who renounced expensive military adventures, led to the crisis being overcome. In Germania, the reconstruction of the many destroyed cities and forts, including the city of Kempten (Cambodunum), the then provincial capital of Raetia, began . In 73/74 AD Vespasian had the imperial border shortened in what is now south-west Germany: With the construction of the Kinzigtalstrasse and the establishment of the Alblimes , at least part of the so-called Dekumatland ( agri decumates ) came under Roman rule. This made it easier to move troops from the Danube to the Rhine (and vice versa). In order to prevent new revolts, but also to relieve the state finances, Vespasian had the legions in Germania reduced, large locations divided and the troops mixed more nationally.

reception

The most important artistic adaptation of the Batavian Uprising is the series of etchings of Batavorum cum Romanis Bellum by Antonio Tempesta, published in Antwerp in 1612, based on (now lost) models by Otto van Veen . In 1661 Rembrandt used a sheet from the Tempestas series as inspiration for his painting The Batavian Conspiracy for the Stadhuis of Amsterdam , which was only removed again for unexplained reasons shortly after its installation and can now be seen in the National Museum in Stockholm - cropped on all sides . Most of the paintings by other artists with subjects from the history of the Batavians in the Stadhuis, including Ferdinand Bol and Jacob Jordaens , are also based on the illustrations etched by Antonio Tempesta.

literature

- Bruno Bleckmann : The Teutons. From Ariovistus to the Vikings. Beck, Munich 2009, ISBN 978-3-406-58476-3 , pp. 137-145.

- Dirk Schmitz: The Batavian uprising in the context of the Roman civil war 68-70 AD. In: Martin Müller, Hans-Joachim Schalles , Norbert Zieling (ed.): Colonia Ulpia Traiana. Xanten and its surrounding area in Roman times (= history of the city of Xanten. Vol. 1). von Zabern, Mainz 2008, ISBN 978-3-8053-3953-7 , pp. 117-140.

- Dieter Timpe : Tacitus and the Batavian Rebellion. In: Tassilo Schmitt , Winfried Schmitz , Aloys Winterling (eds.): Present antiquity - antike present. Colloquium on the occasion of Rolf Rilinger's 60th birthday. Oldenbourg, Munich 2005, pp. 151-187, ISBN 3-486-56754-3 .

- Ralf Urban : The "Batavian Uprising" and the uprising of Iulius Classicus (= Trier historical research. Vol. 8). Trier historical research, Trier 1985, ISBN 3-923087-07-1 .

Web links

- Brief overview with map and references

- Jona Lendering: Batavian Revolt . In: Livius.org (English)

Individual evidence

- ^ Tacitus: Historiae IV / V

- ↑ Tacitus: Historiae IV, Chapter: 13.26 ff.

- ↑ Tacitus: Historiae IV, Chapter 13

- ↑ Tacitus: Historiae IV, Chapter: 26, 32–33, 35–36, 58 ff.

- ↑ Tacitus: Historiae IV, Chapter: 4.13

- ↑ Tacitus: Historiae IV, Chapter 13

- ↑ Tacitus: Historiae V, Chapter: 13-26

- ↑ Tacitus: Historiae IV, Chapter: 21-27

- ↑ Tacitus: Historiae IV, Chapter 14

- ↑ (Tacitus, Historien 4, 13; on this Barbara Levick: Vespasian . Routledge, London 1999, ISBN 0-415-16618-7 , p. 108.)

- ↑ Tacitus: Historiae IV, Chapter: 21 - 457

- ↑ Tacitus: Historiae IV, Chapter: 26 - 37

- ↑ Christoph Reichmann: Gelduba - the Roman fort in Krefeld-Gellep / Museum accompanying document - Chapter IV: Bataverschlacht, p. 18f, Verlag Freunde der Museen Burg Linn eV Krefeld 2011

- ↑ Christoph Reichmann: Gelduba - the Roman fort in Krefeld-Gellep / Museum accompanying document - Chapter IV: Bataverschlacht, p. 20f, Verlag Freunde der Museen Burg Linn eV Krefeld 2011

- ↑ Tacitus: Historiae IV, chapter 58

- ↑ Tacitus: Historiae IV, Chapter: 21 - 57

- ↑ Tacitus: Historiae V, Chapter: 10 - 26

- ↑ Tacitus: Historiae V, Chapter: 14 ff.

- ↑ Tacitus: Historiae V, Chapter: 20ff.

- ↑ Tacitus: Historiae V, Chapter: 23ff.

- ↑ Tacitus: Historiae V, Chapter: 23ff.

- ↑ Tacitus: Historiae V, Chapter: 25ff.

- ↑ Tacitus: Historiae V, Chapter: 24-26