Colonia Ulpia Traiana

The Colonia Ulpia Traiana (CUT) was a Roman city (Colonia) in the area of today's Xanten ( North Rhine-Westphalia ). It existed from about 100 to 275 AD and was a capital of the province of Germania inferior . Today the Xanten Archaeological Park with the LVR Roman Museum is located there . The archaeological monuments in the area are gradually being developed.

The Colonia Ulpia Traiana was founded by Emperor Marcus Ulpius Traianus and named after him. As Colonia , it was one of the 150 or so cities in the Roman Empire that had this highest city charter and were considered "images of Rome". Ulpia Traiana was after Claudia Ara Agrippinensium (today's Cologne ) and Augusta Treverorum ( Trier ) the third largest Roman city north of the Alps . Their public buildings represent the high status of the city, which formed the center for a large surrounding area.

Pre-Colonia settlements

Based on archaeological finds, the location can date back to the 4th century BC. To be traced back. Other finds date from the 3rd century BC. BC, from the 2nd and 1st centuries BC, however, there is no evidence of continuous settlement.

13/12 BC Chr. Was Drusus the military camp Vetera on the nearby Furstenberg building that served as a base for expeditions into the right bank of Germania, which in v. 8 Chr. Led to the fact that the Germanic tribe of Sugambrer was resettled in areas on the left bank of the Rhine. Now known as Cugerner , he founded the settlement that was later to become Colonia Ulpia Traiana .

The name of this settlement has not been passed down. One hypothesis says that it was called " Cugernorum " according to the Batavian capital Batavorum (today's Nijmegen ) . An indication of the possible place name is provided by a dedicatory inscription to Mars Cicollus from the 1960s AD , which has only survived in fragments , in which parts of the first three letters of the place name have most likely been preserved (read as “Cib”, “Cip "," Cir "," Gib "," Gip "or" Gir "). Julianus Egidius Bogaers has suggested adding "Cibernodurum" to this remainder of the name, which could also be derived from the tribal name of the Cugerner (also known as Cuberner).

Due to the proximity to Vetera I, Cugernorum / Cibernodurum developed within a few years to a relatively prosperous trading center until the Batavian revolt 69/70 Fate Veteras informed and was burned. With the rebuilding of Vetera II in 71, the settlement was also re-established. It had a well-developed port and consisted mainly of clay half-timbered houses, the building materials of which came from the surrounding area.

Colonia Ulpia Traiana

Around 100 AD the settlement was raised by Emperor Marcus Ulpius Traianus to Colonia Ulpia Traiana. The old settlement was completely leveled and a new city with an aqueduct , canal system, a right-angled street network, temple, forum, amphitheater, walls and gates was built. Areas that had not been built up were also built on. Therefore graves can be found today within the Colonia, although the burial fields were always outside the settlement. About 10,000 people lived within the walls on 73 hectares. The population consisted of Romanized Gauls and Teutons. With the city elevation, veterans of the Legion stationed in Vetera, among other places, received land and formed a wealthy population.

Various trades are attested in the city. Numerous layers of Roman ceramics came to light near the port in 1993, most of which are false fires that are evidence of a pottery in the city. Further waste from a pottery came to light under the matron shrine in Insula 20 and testify to local ceramic production in the pre-colonial period. Metalworking workshops have been excavated in Insula 39. Above all, silver has been worked here.

According to the archaeological findings and finds, the settlement of Colonia Ulpia Traiana continued to decline in the course of the 3rd century. This is often associated in research with the Germanic raids in the Germanic and Gallic provinces, which increased during this period. In the second half of the century, the arm of the Rhine silted up in front of the city, whereby a natural protective wall of the Colonia fell away. The only clear archaeological evidence of a possible destruction of the city comes from the backfilling of a cellar of the Roman inn , where a layer of fire with a silver coin of the emperor Aurelian (ruled 270-275) was found. It is therefore often assumed that the historically documented extensive looting of the Franks in the years 275/276 caused the city's destruction. In their evaluation of the excavations in the hostel cellar, Bernd Liesen and Marcus Reuter came to the conclusion that the individual find there was insufficient to link the destruction of the entire Colonia Ulpia Traiana with the Franconian raids or even the violent destruction of the hostel to claim.

Post-colonial settlement

It was not until around 310 that the Colonia was re-established within its old walls as Tricensimae on the nine central insulae as a strongly fortified, not purely civilian settlement and without city rights. As the most important fortress of Lower Germany, it took over the function of the also destroyed Vetera II as a camp of Legio XXX Ulpia Victrix until the settlement was taken by Franks in 352. Rebuilt from 359, it was finally abandoned in the first half of the 5th century.

Post-Roman times

The buildings were initially preserved, but the decaying Colonia, with the beginning of the “petrification” of the medieval city, also increasingly served as a quarry. The usable materials were used to build the church and the city of Xanten or sold to Holland - the Roman city gradually disappeared from the surface. Only the Capitol remained a visible ruin until after 1839. After the stones had been cleared away and the subsoil had been ransacked for stones, as shown by entry holes in the remains of the large thermal baths, the area was converted into arable land.

Since the city of Xanten was built on the Roman burial ground, the Roman structures were preserved, unlike in Cologne or Trier , and were only affected by the stone robbery. The first systematic excavations were carried out in the 19th century by the Niederrheinischer Altertumsverein , which were continued in the 1930s as part of the construction of Bundesstraße 57 and made the Roman city known again. Further excavations followed in the 1950s and 1960s. From the 1970s, individual buildings in the former city were reconstructed as part of the Xanten Archaeological Park , which has now been extended to almost the entire former city.

buildings

The city wall of Colonia Ulpia Traiana enclosed the 73 hectare city over a length of 3.4 km. Inside, the settlement was divided into insulae by streets intersecting at right angles . These are modernly numbered from 1 to 40. In the center of the city (Insula 25) was the forum , which took up a complete insula.

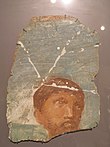

Insula 26 to the south of it accommodated the Capitol . Like the other large buildings of the CUT, it was built in the second century, although the area was previously densely populated with houses, some of which were richly decorated with paintings. The actual Capitol extended over a large district. The temple was oriented to the northeast, towards the Rhine. Only foundations could be excavated, although ruins could still be seen up to the beginning of the 19th century and the first excavations in the temple took place at this time.

To the north-west of the forum were the thermal baths , which in turn took up an entire insula (10). The so-called administration palace, the function of which has not yet been sufficiently clarified, occupies the three insulae (4, 11 and 17) west of the forum. Other important public buildings were the amphitheater of Colonia Ulpia Traiana in the south of the city (Insula 40) and the great port temple (Insula 37). With the matron temple , a smaller matron shrine could be excavated within the residential development (Insula 20). On Insula 38, right next to the small port gate, and thus at the port, was the hostel with the hostel thermal baths.

The individual insulae of the private residential and commercial areas were parceled out. The individual plots were about 12 × 44 m in size. They are mostly strip houses . Some of the houses were richly decorated with wall paintings , but so far there is no evidence of mosaics . So far, no atrium or peristyle houses have been found. The city differs significantly from Cologne in these points . In Insula 3, a larger house was excavated, which with its corner projections resembles a villa rustica rather than a town house. The building was over 20 m long, with the corner projections facing the courtyard, while there were colonnades on the street front . Some rooms in the house had hypocausts . Several residential buildings were excavated in Insula 19. Here you can find high-quality wall paintings, including the so-called eagle giant wall.

Water supply

The numerous wells found in the area of the CUT alone were not enough to supply a city of this size with sufficient quantities of drinking and industrial water. Remnants of water pipes were found in some places in the Xanten area as early as the 19th century and after the Second World War in the Xanten urban area, but for a long time they did not reveal any clear connection. However, only the Hees or the “Sonsbecker Heights” could be considered as a water catchment area .

In 1959, Hermann Hinz discovered a line leading from the compression moraines of the "Hees" through what is now Xanten and along the former grave road that reached CUT from the south. In 1975, in connection with road construction work in the Sonsbeck district of Labbeck , it was possible to find a piece of the supply line that was used to transport the surface water from the Sonsbeck heights to the CUT. It was a mortar channel with broken bricks that still contained traces of the typical lime sintering . The foundation was solidly made of Eifel greywacke , basalt and tuff stones. Slate fragments indicated the former cover of the channel, which had a gradient of 20 cm by 100 m. Part of this aqueduct was moved to the Xanten Archaeological Park and preserved.

In May 2007, during dry weather, during overflights by the aerial photo archaeologist Baoquan Song from the Ruhr University Bochum, clear anomalies of vegetation were found, which indicated a row of aqueduct piers in the so-called “Furth”. There were further references to sections of the aqueduct at the Hasenacker forester's lodge. Excavations in December 2008 confirmed the aerial photos. During construction work in the area of the Xanten market square at the end of 2009, remains of the foundations of the water pipe were found.

See also

literature

- Landschaftsverband Rheinland, Rheinisches Landesmuseum Bonn (Ed.): Colonia Ulpia Traiana series . Rheinland-Verlag, Cologne.

- Work report 4. On the excavations and reconstructions . 1980, ISBN 3-7927-0552-4 (= guides and writings of the Xanten Archaeological Park 5).

- Work report 5. On the excavations and reconstructions . 1981, ISBN 3-7927-0608-3 (= guides and writings of the Archaeological Park Xanten 6).

- Work report 6. On the excavations and reconstructions . 1984, ISBN 3-7927-0794-2 .

- Work report 7. Excavation, research, presentation . 1992, ISBN 3-7927-1240-7 .

- Christoph B. Rüger : Colonia Ulpia Traiana . In: Heinz Günter Horn (Ed.): The Romans in North Rhine-Westphalia. Licensed edition of the 1987 edition. Nikol, Hamburg 2002, ISBN 3-933203-59-7 , pp. 626–638.

- Ursula Heimberg , Anita Rieche : Colonia Ulpia Traiana. The Roman city. Planning - architecture - excavation . Rheinland-Verlag, Cologne 1998, ISBN 3-7927-1725-5 ; Habelt, Bonn 1998 (= guides and writings of the Archaeological Park Xanten 18).

- Brita Jansen: The Roman wall paintings from the urban area of Colonia Ulpia Traiana. Volume I: The finds from private buildings . Zabern, Mainz 2001, ISBN 3-8053-2873-7 (= Xantener reports , volume 11).

- Martin Müller , Hans-Joachim Schalles , Norbert Zieling (eds.): Colonia Ulpia Traiana. Xanten and its surroundings in Roman times (= history of the city of Xanten. Volume 1). Philipp von Zabern, Mainz 2008, ISBN 978-3-8053-3953-7 .

- José Remesal Rodríguez (Ed.): Colonia Ulpia Traiana (Xanten) y el Mediterráneo. El comercio de alimentos. Publicacions. Universitat de Barcelona, Barcelona 2019, ISBN 978-8-4916-8197-7 .

Web links

- Xanten Archaeological Park

- The Xanten room in antiquity

- Jona Lendering: Xanten: CUT . In: Livius.org (English)

Individual evidence

- ^ First proposed by Franz Oelmann : Report on the activities of the State Museum in Bonn from April 1, 1934 to March 31, 1935. In: Bonner Jahrbücher . Volume 140/141, 1936, pp. 429-464, here p. 431.

- ↑ AE 1981, 690 .

- ↑ Julianus Egidius Bogaers: On the name of the "oppidum Cugernorum". In: Naamkunde. Volume 16, 1984, pp. 33-39 ( digitized version ).

- ↑ Landschaftsverband Rheinland (Ed.): Monument to nature. Protection of nature and soil monuments in the Xanten Archaeological Park . Kleve 2003, p. 18.

- ↑ Ulrich Boelicke: Waste from a newly discovered Roman pottery , in: Tatort CUT, The trace leads to Xanten , Cologne 1995, ISBN 3-7927-1503-1 , 51–54

- ↑ Dagmar Kroemer: Ceramic production in the pre-colonial settlement , in: Tatort CUT, The trace leads to Xanten , Cologne 1995, ISBN 3-7927-1503-1 , 658-64

- ^ Norbert Zieling: Metal processing in the Colonia Uplia Traiana , in: Tatort CUT, The trace leads to Xanten , Cologne 1995, ISBN 3-7927-1503-1 , 65-70

- ↑ Landschaftsverband Rheinland (Ed.): Monument to nature. Protection of nature and soil monuments in the Xanten Archaeological Park . Kleve 2003, p. 20.

- ↑ Bernd Liesen, Marcus Reuter : The cellar of the mansio in Insula 38 and the end of the Colonia Ulpia Traiana. In: Xantener reports. Volume 15, 2009, pp. 279-312 ( online ).

- ↑ Landschaftsverband Rheinland (Ed.): Monument to nature. Protection of nature and soil monuments in the Xanten Archaeological Park . Kleve 2003, p. 23.

- ↑ Landschaftsverband Rheinland (Ed.): Monument to nature. Protection of nature and soil monuments in the Xanten Archaeological Park . Kleve 2003, p. 24.

- ↑ Landschaftsverband Rheinland (Ed.): Monument to nature. Protection of nature and soil monuments in the Xanten Archaeological Park . Kleve 2003, p. 26.

- ↑ Landschaftsverband Rheinland (Ed.): Monument to nature. Protection of nature and soil monuments in the Xanten Archaeological Park . Kleve 2003.

- ↑ The archaeological park has been expanded. Retrieved March 28, 2020 . on apx.lvr.de (official website of the archaeological park Xanten)

- ↑ Ursula Heimberg: Bonner Jahrbücher 173 (1973), pp. 350–351.

- ^ Michael cell, In: Brita Jansen, Charlotte Schreiter, Michael cell: The Roman wall paintings from the urban area of Colonia Ulpia Traiana , pp. 124-137.

- ↑ Werner Böcking: The water pipe of the ancient city . In other words: The Romans on the Lower Rhine. History and excavations . Klartext, Essen 2005, ISBN 3-89861-427-1 , p. 187.

- ^ Hermann Hinz: Roman aqueduct south of Xanten. In: Bonner Jahrbücher 159, 1959, pp. 134–148.

- ↑ Werner Böcking: A Roman aqueduct is discovered . In other words: The Romans on the Lower Rhine. History and excavations . Klartext, Essen 2005, ISBN 3-89861-427-1 , pp. 263-266; Hans-Helmut Wegner, Ursula Heimberg: Water for the CUT. Remains of Roman aqueducts from Colonia Ulpia Traiana near Xanten . In: The Rheinisches Landesmuseum Bonn 6/75. Rheinland Verlag, Bonn 1975, p. 81ff .; Christoph B. Rüger: Colonia Ulpia Traiana . In: Heinz Günter Horn (Ed.): The Romans in North Rhine-Westphalia. Licensed edition of the 1987 edition. Nikol, Hamburg 2002, ISBN 3-933203-59-7 , pp. 635–636 and figures 543 and 549.

- ↑ Christoph Ohlig: The water line to Colonia Ulpia Trajana . German Water History Society, Siegburg 2007, ISBN 978-3-8334-8433-9 , (Writings of the German Water History Society , 11/1), p. 186ff.

- ↑ How the water came to Xanten ( Memento from October 15, 2013 in the Internet Archive ), press release of the Rhineland Regional Association / Rheinisches Amt für Bodendenkmalpflege.

Coordinates: 51 ° 40 ′ 0 ″ N , 6 ° 27 ′ 0 ″ E