History of the city of Bonn

Bonn's city history has its origins in a Germanic settlement. After the establishment of a Roman exploratory camp in the time of Emperor Augustus on the left side of the Rhine ,a legionary camp was established after the Varus Battle . After a loss of importance in Franconian times, Bonn gainedincreasing importanceas a city in the Middle Ages and became the residence of the Cologne electors in the 16th century. From 1815 to 1945 Bonn belonged to Prussia .

After the Second World War , Bonn was the capital of the Federal Republic of Germany until 1990 and the seat of government until 1999 . In the course of the Unification Treaty , Berlin was declared a federal capital in 1990 and Bonn a federal city.

Stone Age and Early History

Long before the beginning of the era , people lived in the Bonn region. The slightly elevated location on the Rhine favored these settlements.

Finds in the entire city area of Bonn testify to this, which document settlement activities for almost all prehistoric times - from the Paleolithic to the time of the Teutons . A dozen hand axes, found in the Bad Godesberg district of Muffendorf, were dated to the Paleolithic (around 50,000 BC).

Two well-preserved skeletons of the double grave of Oberkassel are the oldest finds of anatomically modern humans ( Homo sapiens ) in Germany. The human remains of the 50-year-old man and the 20- to 25-year-old woman are around 14,000 years old. In addition to the female and male skeletons, according to the find report by Professors Verworn, Bonnet and Steinmann from February 18, 1914, skeletal remains of a dog and jewelry were found in the Oberkassel basalt quarry. They are classified as an advanced type of Cro-Magnon .

A trench and wooden palisades , which have been proven in the area of the Venusberg and date from around 4080 BC. B.C. belong to the finds that prove settlement activities in the left bank of the Rhine area of Bonn. Whether this is a “ refuge ” or a fortified settlement can only be clarified after further excavations within the area.

Hallstatt and Latène Period

The roughly 600 years before Christ are largely in the dark. Probably the Hunsrück-Eifel culture shaped the region on the Marne , Saar , Moselle and Middle Rhine until the arrival of the Romans . However, these times give clues about the origin of the name. It may have been a Celtic settlement from which the name Bonn goes back. Bona means in Celtic "foundation, tribe" (cf. Old Irish bonn , Welsh bôn ) as with the many Bonnes, Bonne in France. As a component, the bona can be found in Vindobona "white village"> Vienna and Ratisbona "fortified village"> Regensburg . According to another interpretation, Bonn describes the ridge that extends from Graurheindorf in the north over the Belderberg to today's Koblenzer Strasse in the south at a height of 15 m above the Rhine. The Celtic variant of meaning "sole, support, base" (cf. Central Irish bond , bonn ), which, with the Latin equivalent ( Latin fundus "ground, ground, property, estate"), refers to a Gallic * bonum to be reconstructed in Gallic , * bona can be concluded with meanings such as “base, flat ridge, fortified base, castle”. This would then apply well to the pedestals in the Bonn city area, which can be proven to have already been settled in pre-Roman times, as well as in the area of the “ vicus bonnensis ” excavated in 2006 at the Bundeshaus (see below).

Teutons and harbingers of Roman occupation

In the last century BC Sugambrers settled on the right bank of the Rhine and Eburonen on the left bank of the Rhine .

The Roman era on the Rhine began with the advance of a Roman legion under Julius Caesar in 55 BC. To the Rhine.

After Caesar had defeated the tribes who settled here during his campaigns and completely ousted them from the area of the Middle and Lower Rhine , Ubier followed them . In the period between 39/38 BC BC and 20 BC The Roman governor in Gaul , Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa , settled the Ubier from the Neuwied basin in the Bonn area. However, the main residence of the resettled Ubioum is the oppidum Ubioum , from which Cologne will later develop.

The Romans in Bonn

Reconnaissance camp

In connection with exploratory campaigns and campaigns, Roman soldiers also came to the settlement of the West Germanic Ubier on the Rhine and built on the site of what is now Bonn's inner city from 18 BC. A reconnaissance camp, a so-called auxiliary camp , which was built around 12 BC. Was expanded to a fort.

The Rhine now formed the border between Romans and Teutons. The Lower Germanic Limes (also called "Nasser Limes") between the North Sea near Katwijk in the Netherlands and Bad Breisig south of Bonn was one of the most important external borders of the mighty Roman Empire.

In 13 BC BC Emperor Augustus gave his stepson, the general Nero Claudius Drusus , the order to build 50 forts along the Rhine. Augustus's aim was to build forts on the Rhine as fortified weapon locations in order to create a base of operations for the conquest of Germania as far as the Elbe , as Lucius Annaeus Florus reported a century and a half later .

In the year 12 BC In BC Augustus began a war against the Teutons, which led the Roman troops far across the Rhine to the Elbe . Roman advances ( Drusus campaigns ) took place in the area of the Chatti, Cheruscans and the North Sea coast, but failed in 9 AD after the grueling defeat of the general Publius Quinctilius Varus in the Battle of Varus . At this time Germanic tribes such as Ubier, Batavians and Texuanians , Celtic-Germanic tribes such as Vangioner and Nemeter , and Celtic tribes such as the Treverer settled on the Roman Empire .

Both the Ubian settlement and the presence of Roman soldiers are documented by archaeological finds. The Ubic settlement was on the left bank of the Rhine between the Rhine and Gumme , where the university and the minster are today . There is no precise time when the Romans first came to this settlement. It must have been in the period between the preparation or the beginning of the war and the death of Drusus - 9 BC. BC - have been. When Bonn celebrated its 2000th birthday in 1989, the year 11th BC was chosen. " Since the exact year cannot be determined ," said the then Mayor Hans Daniels , "we decided on the year 11, the middle between 13 and 9."

In addition to archaeological finds in the Bonn city area, there is a literary source that is cited to prove the presence of Roman soldiers in the time of Drusus. It is the two-volume work Epitoma de Tito Livio bellorum omnium annorum DCC libri duo by the Roman writer Florus . In it the author mentions a place name, which is read differently in the manuscripts on which it is based. One reading is "Bonna". With him it is then according to this reading: "Bonnam et Gesoriacum pontibus iunxit classibusque firmavit." Translated: "He (Drusus) connected Bonna and Gesoriacum with bridges and strengthened them with a fleet." Not just since the 2000 anniversary of Bonn this point was used as evidence that there was a Roman bridge in Bonn, which is very controversial today.

Altar for Mercurius Gebrinius (2nd half of the 2nd century) - place of discovery: Bonn Minster

Portrait of a Roman woman (180/200 AD) - location: Bonn- Schwarzrheindorf

Roman legion camp

After the defeat against the Teutons in the Varus Battle in 9 AD, the Romans began building a fortified camp (Drusus fort) in order to secure the border on the Rhine. The camps on the right bank of the Rhine were abandoned. Excavations in 1952 locate this Drusus fort in the area of the Bonn town hall on the market.

In the year 16 BC The Roman governor Marcus Lollius suffers a defeat with the Legio V Alaudae in the fight against the Sugambri, Tenkerites and Usipeters near Bonn.

Around 17 AD, the Romans created an auxiliary camp in the northern part of the Ubier settlement .

Around 30 AD the Legio I Germanica was moved from Cologne to Bonn, which required the construction of a new camp, which was now further north than the already existing Drusus fort. It was opposite the confluence of the Sieg in the Rhine on the Roman Rhine Valley Road . As a result of the conversion of the nearby Colonia Claudia Ara Agrippinensium (later Cologne) into a civilian settlement, the Legio I and two other auxiliary units were stationed in the wood / earth warehouse . This troop, around 7,000 strong, expanded the camp in the following years as part of the Roman defense line on the Rhine. The almost square fortress had an area of 528 by 524 meters with a port facility that was naturally bounded by the Rhine in the east and can still be seen in its ground plans at low tide. In the final stage it held 10,000 soldiers and was around 25 hectares in size. In front of the camp, at today's Wichelshof, the Romans built a port basin around 350 m long. The outlines of the fortress are still marked today by the banks of the Rhine, Rosental, Rheindorfer Straße and the Augustusring. A Roman provincial road ran through the camp in a north-south direction, which essentially followed today's federal road 9 .

Canabae and vicus bonnensis

In the vicinity of the camp, the “ canabae legionis ”, and in a settlement further south, the “ vicus bonnensis ”, craftsmen (such as masons, potters, stonecutters, blacksmiths and Carpenters, butchers and bakers, tanners and saddlers, walkers and rope makers) and traders. Weapons workshops, glass smelters and potteries were built. Traders, merchants, pawnbrokers and money changers went about their business. The health service was represented by doctors and pharmacists. Estimates suggest that up to 10,000 people lived in the Bonn area who lived according to the laws of a highly differentiated division of labor.

Under the Roman governor A. Pompeius Paulinus, the Bonn legionary camp received a solid stone wall in 54–56.

During the Batavian revolt in 69 the Roman camp fell but was quickly rebuilt.

Around the year 70 the Legio XXI Rapax (nickname "the Fast", originally from Vindonissa ) was relocated to Bonn and replaced the Legio I Minervia .

- Finds from the vicus

Cellar of a Roman house that belonged to the "vicus". Preserved in the Roman cellar of the House of History in Bonn

From May to October 2006, archaeologists examined the four football fields to the west of the Federal Palace where the new congress center was being built. They found remains of the vicus bonnensis . Jürgen Kunow , the head of the Rhenish Office for the Preservation of Ground Monuments , commented while presenting the finds: “We found far more than we had expected. The life of Roman citizens on the Rhine has never looked like this for us. ” In addition to the approximately 60,000 broken pieces, a precious hairpin made of bones with a stylized human head was found, a unique find in Germany. The remains of monumental stone buildings are just as much a part of it as a bathing complex equipped with underfloor heating , a brick kiln and a square Gallo-Roman temple. All in all, a settlement with an urban character is now assumed, not just a village-like complex. Potters and glassblowers had their workshops here, as shown by pits filled with clay and a glass river. The settlement also included so-called strip houses made of timber framework, the remains of which were also found, as well as huge clay u. Garbage pits. It is suspected that it has its own dock on the Rhine nearby. In the near and far Bonn area, farms were established that were connected to the garrison by a network of roads and roads. Place names of today's Bonn districts (for example Endeich, Kessenich or Lessenich) are reminiscent of the Roman past. LVR archaeologists have been talking about the Roman civilian settlement (vicus) of Bonn since the excavation when referring to these new finds. They have been dated from the 1st to the 3rd century.

So far, however, no researcher has clarified the relationship between the “settlement core” discovered here and the civilian settlement that stretched between Kölnstrasse and Belderberg into the area of the historic old town (i.e. not Nordstadt, but where the Beethoven Hall and Opera are today , Theaterstrasse, Oxfordstrasse). This area was regularly referred to until 2006 when the civil settlement was mentioned; the extent of the settlement in the government district was not known. The settlement was called "canabae legionis" by archaeologists, "suburb" of the legion fortress in what is now Bonn-Castell. But only one of the two places will have had the name Bonn; Since burials were carried out along the Adenauerallee (between the two “settlement centers”), but burials were only carried out out of town, the “vicus” is more of a neighboring place and in any case is not directly connected to the Roman Bonn.

Burial grounds

Graves have been found in the area of the vicus bonnensis . Burials are also known from the area between the vicus and the military camp. Cemetery sections with cremation and body graves were discovered several times in the vicinity of the camp . The military camp also includes a larger cemetery section on Irmintrudisstrasse with around 300 late antique burials.

"Bonna" at Tacitus

A much more reliable source for the name "Bonna" or "Castra Bonnensia" than the text by Florus are the " Histories " of Tacitus . In his description of the Batavian uprising in 69/70 he mentions "Bonna" in several places. This also applies to the legionary camp ("castra Bonnensia"). Whether "Bonna" was the name of the place at this time - possibly even earlier - cannot be definitively clarified by the "Histories", because they did not appear until 40 years after the uprising. Renaming of places was not uncommon.

Following the Batavian uprising reported by Tacitus and the associated destruction of the Bonn camp, a new camp, now made of stone, was built in the same place and was completed in 80. The Legio XXI Rapax stationed here was replaced by the Legio I Minervia in 83 . The Bonn aqueduct was built to supply the castra Bonnensia with drinking water and was completed in 83.

The matron cult flourished in Bonn and the surrounding area in the 2nd century . Up to 17,000 people, including about 7,000 members of the military, lived in Bonn in the 2nd century. In 252 the two Romans Venconius and Julius Felix consecrated an altar to Jupiter in Bonn .

The franc incidence in 274 n. Chr. Did not lead to current knowledge, to the destruction of the camp. However, the residential areas outside the camp were given up, the remaining civilian population lived in the camp itself with the military unit, which was soon reduced to 1,000 men. Burials were concentrated around the camp and the area around Münsterplatz . A "small necropolis " was built there in the second half of the 3rd century .

There is evidence that the camp was destroyed by the Franks in 353; since then there have been no reports of Legio I, which some researchers believe had been largely wiped out as early as 351 in the battle of Mursa . Julian had the camp rebuilt around the year 357, fortified and equipped with storage structures. Whether it was the same size as the previous one is disputed among historians.

The Roman administration of the province of Germania II functioned in some areas until the middle of the 5th century. This can possibly also be assumed for the Bonn camp, as indicated by the grave find of a Germanic warrior in Roman service from the first third of the 5th century, who was buried in front of the eastern wall of the camp. Little is known about the condition of the camp in the following decades and centuries. It later traded under the name "Bonnburg"; strategic importance can hardly be assumed. An early church complex, the later “Dietkirche” (= Volkskirche), was probably built around 795 in the Franconian- Merovingian period as the first parish church in the area of the former camp. It preceded today's cathedral as a Christian place of prayer and assembly in Bonn.

Period of the Franks (Merovingians and Carolingians) - Bonnburg and Bonngau

With the Franks incursions in the last quarter of the 3rd century, the decline of Roman Bonn began and the population of Bonn shrank to 3,000 to 4,000 people. Around 458 the Roman general Aegidius gave up the Rhine border and withdrew to the south. In 475 the Franconian Ripuarians finally ousted the Romans from the Rhine with the conquest of Trier and established an independent empire between the Rhine delta and Trier, the Francia Rhinensis , with the capital Cologne as its center. The Franconians referred to the Franconian fiscal estate Bonn, referring to the Roman fort, also as "Bonnburg" or "Castrum Bonna".

Around 540, the Frankish king Theudebert I from the Merovingian family in Bonn had coins minted for the first time.

From the 7th century and then completely in the 9th / 10th centuries. In the 19th century, the focus of Bonn's settlement shifted to the areas of today's city center: to where the market is today and to the area of today's cathedral. The name of this settlement area is "villa basilica". A grave field has been located here since Roman times.

Where the cathedral was built in the middle of the 11th century, a hall was built in the Merovingian period, in the middle of the 6th century. It rose above the place where a Roman memorial to the dead, a cella memoriae , had been in late antiquity . The hall building was a stone building that stood on mighty foundations made from second-used matronal altars and other ancient spoils . Graves were dug in the building and outside, and the dead were buried until the end of the 8th century.

At the end of the 7th century at the latest, clerics settled in the place and the appearance of the hall building was repeatedly changed through additions and renovations. Two burial chapels and several living and utility rooms were added. In the following centuries the building was considered to be the burial church of the two Christian martyrs Cassius and Florentius . With the establishment of a monastery in Carolingian times (canons monastery ) it became the collegiate church “St. Cassius and Florentius ”(“ Basilica sancta Cassii et Florentii ”). The deacon and abbot Giso is mentioned in the oldest document of the Cassius monastery in 691. This old collegiate church was demolished in the 11th century and the minster was built in its place. The settlement surrounding the minster was initially called Verona by the church , a name that can also be read on the coins minted here. While Cologne joined forces with the proud Roman Empress Agrippina and Xanten in the Lower Rhine region called itself Troy, Bonn decided on Verona. In the long run, however, he was unable to assert himself against Bonn ( Bunne in the local dialect ), which was preferred by the population .

The Franconian Ripuaria is organized as a duchy around 680. It consists of 8 districts (pagi). The Bonngau (sometimes also called Ahrgau ) extends to the left of the Rhine from Wesseling to the Vinxtbach near Brohl . This spatial planning will be retained until the reorganization of the Carolingian Empire under Charlemagne . In the 8th century a settlement in the area of today's marketplace is called "vicus Bunnense", which was initially a small settlement for long-distance traders.

To secure the Rhine border, a Carolingian castle is being built on the right bank of the Rhine in Schwarzrheindorf . Geislar is mentioned for the first time in 873 .

Around the year 881 the Carolingian Empire began to show signs of disintegration. During the Viking raids in the Rhineland , Bonn was burned twice in 882. In the year 883 the city, which had just been rebuilt and now fortified, was attacked, sacked and plundered once more by the Normans . In 891 the Normans occupied Bonn again.

In the year 913 a brother of the East Franconian King Konrad I, named Eberhard, was named as " Graf des Bonngau " in a document .

On November 7th, 921, Charles the Simple and Heinrich I signed the " Peace of Bonn " on a ship anchored in the Rhine : The West Frankish King Karl recognized Heinrich I as King of the East Franconia on an equal footing.

Flowering in the high and late Middle Ages

Around the turn of the millennium, the focus of the settlement - and with it the place name - shifted from the Bonnburg to the monastery town and the bourgeois market settlement in front of it, which was built on archbishop's land and was called " oppidum Bonnense " in 1211 ,

In the course of the 11th and 12th centuries, these two new settlement centers enlarged. In the High Middle Ages and the Late Middle Ages , Bonn was able to expand its economic and cultural importance on the right and left banks of the Rhine. There was a farmer's settlement and the wine trade was profitable. Wealthy clergymen and canons - the inhabitants of the monastery, the "Villa Basilica" - were a class of buyers for high-quality products. They ensured that the market settlement expanded and the number of traders, merchants and craftsmen increased. Bonn experienced a heyday and prosperity. Today's minster is a building from the 11th to the early 13th century, with the east choir from the middle of the 12th century (client: Provost Gerhard von Are) having a particular style.

In 1210 the foundation stone of the Godesburg was laid, the northernmost hilltop castle on the Rhine. At the beginning of the 13th century, an Augustinian convent was founded in Godesberg, which adopted the Birgitten rule in 1450 (Marienforst). A commander of the Teutonic Order came into being in Muffendorf.

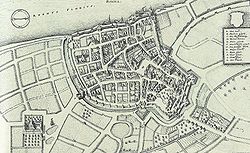

In order to secure these settlement areas, Archbishop Konrad von Hochstaden ordered in 1244 that the populated area between Münster and the Rhine should be surrounded by a city wall. By the end of the 13th century, a wall was built around the monastery city, as a sign that the process of becoming a city of Bonn was completed. The Archbishop of Cologne, Siegfried von Westerburg, completed Bonn's legal status as a city in 1286 by introducing the council constitution. A mayor was mentioned for the first time in 1331. Bonn became the seat of an Electoral Cologne Office and Upper Office, and for a long time it had been a market, customs and mint.

In addition to the Cassiusstift there was a Benedictine convent, which was founded shortly before 1015 in a late antique parish church (Dietkirche) built in the former legionary camp and which adopted the monastery constitution in the 15th century, an Augustinian convent (Engelthal) built in 1324, a minorite convent (since 1274) and numerous other smaller, partly only short-lived spiritual communities. A Cistercian convent was built in the 13th century in Graurheindorf, which is located outside the city wall but is part of the urban area together with Dransdorf.

Bonn Jews are first attested in 1096. In the 12th century, the community owned important scholars such as the crusade writer Ephraim von Bonn . In the years 1348–1349, the Jews of Bonn fell victim to the plague pogrom . A Jewish community in Bonn seems to have existed continuously since the end of the 14th century.

Bonn on the right bank of the Rhine belonged - with the exception of Vilich and Schwarzrheindorf - to the territory of the Counts of Sayn , after 1246 of the Lords of Blankenberg and von Löwenberg and became part of the county or the Duchy of Berg in the 14th and 15th centuries . The last Count of Sayner, Heinrich III., Founded a branch of the Teutonic Knight Order in Ramersdorf soon after 1217 . Benedictine convents were founded in Vilich (around 978, first abbess was Saint Adelheid, who has also been the city patroness of Bonn since 2008) and in Schwarzrheindorf with its art-historical double church of St. Maria and Clemens (after 1156), which were later converted into women's monasteries. Both belonged to the territory of the Electorate of Cologne as so-called subordinates.

Electoral Cologne residence

After the Battle of Worringen in 1288, Bonn became one of the preferred residences of the Cologne electors .

In 1597 Bonn, with an estimated 3,000 inhabitants, officially became the royal seat of Kurköln , the secular territory of the Archbishops of Cologne, under Ferdinand of Bavaria , coadjutor of Elector Karl Theodor . The favorable traffic situation on the Rhine, a differentiated trade, (long-distance) trade and the increasing residential function created the prerequisites for positive urban development.

Ten years earlier, in 1587, troops of the deposed Elector Gebhard I von Waldburg had conquered and devastated the city during the Syrian War . The city, occupied by Gebhard's supporters, was besieged by the Spaniards for six months in 1588 and finally captured.

From the dispute with Gebhard, Duke Ernst of Bavaria from the House of Wittelsbach emerged victorious. With him the epoch of the electoral Cologne rulers from the House of Wittelsbach began. Ernst von Bayern was followed by Ferdinand of Bavaria in 1612 , then Maximilian Heinrich . Joseph Clemens and - as the last Wittelsbacher - Clemens August . At the end of the electoral era it was a Habsburg - Maximilian Franz , Maria Theresa's youngest son - who resided in Bonn.

Expansion to a royal seat and efforts to reformation

A “court of the archbishop” in Bonn is mentioned as early as 1112, which was expanded in the 13th century by Engelbert II von Falkenburg into a palace with a hall and chapel. This began the first frequent and later permanent residence of the Archbishops in Bonn, especially after Siegfried von Westerburg lost his capital Cologne after the Battle of Worringen in 1288.

After 1500, a permanent presence of the electors in Bonn is documented, who accordingly moved the Electoral Cologne Chancellery ("Kanzley"), the heart of the archdiocese administration, to Bonn in 1525 and officially elevated Bonn to the capital and residence city in 1597. A " Council and Chancellery Regulations " document this in writing.

The elector himself moved to Bonn in 1601. With the electoral civil service, the traditional upper class of the city was joined by a group of well-educated councilors of bourgeois origin who also took on municipal offices.

Between 1515 and 1547 there were attempts at the Reformation at court. In 1515 Hermann V von Wied became elector and archbishop of Cologne. Pope Leo X awarded him the pallium . Hermann V tended towards the Reformation Catholicism of Erasmus of Rotterdam , convened councils, had the electoral parliament deliberated on several occasions and thus largely met with approval from the population. Exponents of the Bonn Reformation attempt were the Alsatian reformer Martin Bucer , a colleague of Martin Luther , on the one hand and as an adversary and supporter of the counter-movement Cardinal Johannes Gropper . The efforts called from 1543 onwards Emperor Charles V and the curia. The trigger was a book printing, commissioned by Prince Elector Hermann V, of around 33 Reformation publications in April 1543, which was carried out by the book printer Laurenz von der Mühlen in Bonn. On August 17, 1543, Emperor Charles V and his troops entered Bonn "peacefully" after his soldiers had trampled fields and vineyards for days. The consequences were foreseeable: Martin Bucer had to leave Bonn immediately. The elector was on April 16, 1546 by Pope Paul III. excommunicated and Adolf von Schauenburg was appointed the new elector by the estates under pressure from the emperor. On February 25, Hermann V renounced his electoral status, retired to his home in the Neuwied area and died there in 1552.

Archbishop Salentin von Isenburg had already taken into account the growing importance of Bonn in 1575 with an extensive Renaissance building on the south side of the city, next to today's Old Customs .

The further expansion was interrupted in the next decade by the Truchsessian War (1581–1584). In 1584 the city was captured by the opponent of the deposed Gebhard Truchsess von Waldburg , Duke Ernst of Bavaria , after a month's wintry siege. In the course of the war, Godesburg was blown up by Bavarian troops in 1583 . The Poppelsdorf moated castle was also destroyed.

On December 23, 1587 Bonn was attacked, looted and occupied by Gebhard's partisan, Martin Schenk von Nideggen . The mercenary army leader Nideggen acted on behalf of Count Adolf von Neuenahr , who had entered Dutch service with the rest of the Truchsessian troops. The city is not only sacked by the mercenaries. Nideggen imposes heavy contributions on its citizens .

It was not until September 26, 1588, that Spanish and German troops were able to recapture the city after heavy bombardment. Nideggen fled to Nijmegen in the Netherlands , where he was drowned in the Rhine on August 11, 1589 and then quartered. The Electoral Cologne War was over. However, at the price that the Spaniards were now occupying forces. But the methods of the occupation remained: the Spanish and Walloon mercenaries of Baron Adolf von Schwarzenberg behaved rudely and ruthlessly. Only after the estates had raised the backward pay of the Spaniards in 1594 could the Spaniards be persuaded to end the occupation and withdraw.

A key result of these disputes was the establishment of almost 180 years of Wittelsbach rule in the Electorate of Cologne. Recatholization and the Counter Reformation were the signs of the times.

Bonn in the 17th century

Bonn in the Thirty Years War

In the Thirty Years' War from 1618–1648, Bonn repeatedly suffered from military campaigns, looting, raids and pillage. For three years from September 1620, Dutch troops lay on the Rhine island of Kemper Werth , the "Paffenmütze", because the Netherlands 'war of independence against Spain (Eighty Years' War) was partly fought on imperial territory.

In 1631 it was the Swedes under Wolf Heinrich von Baudissin , in the next decade Hessian and again Swedish troops who plundered the Rhine Valley. In 1632 the Swedish General Baudissin moved against the Archdiocese of Cologne. There was fighting, looting and pillaging everywhere. In November 1632 the Swedes conquered the Drachenfels and razed the outer works of the castle. But probably shortly afterwards they were expelled by the Spaniards. Around the same time, in 1633, the Löwenburg was destroyed.

Even during the war, under the influence of these threats, work began on re- fortifying Bonn using the bastionary system . It took almost a century to complete. Elector Ferdinand of Bavaria had undertaken a new construction of the residential palace in the protection of this double ring in 1633. “A number of new monasteries had also sprung up in the city in the wake of the Counter Reformation, the settlements of the Jesuits, the Capuchins and the Franciscans. As early as 1646, Matthaeus Merian called Bonn a 'beautiful, funny wolerbawete place, there are also funny chased around, and the air is there uesund'. "

Thanks to Archbishop Ferdinand's clever policy of neutrality , Bonn survived the Thirty Years' War significantly better than many other German cities. Kurköln refused to join the Catholic League , although internally it was pursuing a radically anti-Protestant course. The war hit the surrounding areas around Bonn harder. In 1638, Wolfgang Wilhelm von Pfalz-Neuburg , the Duke of Jülich-Kleve-Berg reported that barely a sixth of the inhabitants in the Bergisches Land had survived.

Bonn after the Peace of Westphalia in 1648

The Westphalian Peace of 1648 also hardly brought any feelings of peace to Bonn: Bonn had to endure further sieges in 1673, 1689 and 1703. The siege of 1689 brought the worst consequences for the city . The French troops called into the country by the Electoral Cologne Minister Wilhelm Egon von Fürstenberg , a partisan of Louis XIV. , Occupied Bonn, whereupon the allied Brandenburg, Imperial, Münster and Dutch troops under the command of Friedrich III. - Elector and Duke of Brandenburg-Prussia enclosed the city in the summer of 1689. The bombardment lasted from July 24, 1689 until the occupation surrendered on October 15, 1689. Most of the new fortifications, bastions and entrenchments had been demolished, and most of the houses had been destroyed in the electoral palace, town hall and many church buildings.

The city, which had hardly been restored in a makeshift manner and had come to rest, had to endure another bombardment during the siege in 1703 in the War of Spanish Succession . Again there was a French garrison in the city and Dutch and imperial troops stood at the gates. Before that, Elector Joseph Clemens went into French exile on October 12, 1702. On May 16, 1703, the French surrendered and surrendered the city after the city had been shelled by hundreds of cannons and mortars.

On May 18, 1703, the 3800-strong French garrison withdrew. Dutch troops and troops from the Westphalian Empire moved into the city. Bonn began to suffer more and more from the billeting of the Dutch, but it was to last until 1715, although the Treaty of Utrecht took place in 1713, since only an imperial convention would clarify the withdrawal of the Dutch and the future razing of the fortifications on the right and left of the Rhine revealed.

Officially, Joseph Clemens regained his electoral rights in 1713, but because of the Dutch soldiery it would take until December 11th, 1715 before the elector regained control of the royal seat of Bonn.

Electoral Cologne royal seat in the 18th century

Electoral Cologne royal seat under Joseph Clemens (Wittelsbacher)

At the beginning of the 18th century a new era began for Bonn, a time full of courtly splendor and princely willingness to build. The city was successively the residence of two of the most powerful and enterprising builders among the absolutist ruling princes.

In 1697, Elector Joseph Clemens gave the starting signal to erect a massive new castle on the site of the castle that had been destroyed in 1689 . The Italian master builder Enrico Zuccalli had already built the south wing of the main facade facing the courtyard garden when the elector had to flee from Bonn to France in 1702. That is why the construction remained unfinished for the time being. When the Elector was allowed to return after the Peace of Baden in 1715 , he immediately developed the most lively building activity. The old building plan for the castle was revised and expanded by the French architect Robert de Cotte , and the long gallery wing facing the Rhine was added. Construction began in 1715. The design for the built-in Michael's (Koblenz today Gate) was built around 1725 by the court of the Wittelsbach in Munich making François de Cuvilliés. Ä. , as well as Balthasar Neumann . Michael Leveilly was responsible for the construction .

The minutes of the Bonn city council recorded on June 22nd, 1718 that the razing of the fortifications, initiated in 1715 under pressure from the Dutch, had been completed. Only the Old Customs on the Rhine still reminds of the bastions of that time. The forced removal of the former fortress ring enabled a generous redesign of the city. New streets were built. The original plans of the elector to re-fortify Bonn in 1726 failed due to diplomatic resistance from the Dutch.

Electoral Cologne royal seat under Clemens August (Wittelsbacher)

The second elector willing to build was the successor Clemens August of Bavaria . The generous Clemens August, always concerned about new sources of income, was appointed elector on January 2, 1724 at the age of just 23 (coadjutor from May 17, 1722).

One of the first political decisions was the amalgamation of the Electors of Bavaria, Trier, Cologne and the Palatinate to form the Wittelsbach House Union on May 15, 1724. A special political event was the visit of the Prussian royal family to Bonn on August 8, 1730. Prussian King Friedrich Wilhelm I. came to the electoral residence with his son, who later became King Frederick the Great .

In the first year of office, however, there was initially a power struggle between the city and the elector. The elector, constantly in need of money, intended to add municipal income from the excise to his state income using legal titles. It was not until 1753 that the elector gave in and the confiscated excise was returned.

Gradually, however, he gained a reputation as a builder, patron, heartthrob and hunter - that is, apart from politics. It brought Bonn courtly splendor and prosperity to the citizens and was probably also popular with the population for this reason. Another reason for the popularity was the elector's enthusiasm for balls, masquerades and participation in the Rhenish carnival . A carnival mask parade through Bonn is documented for February 6, 1731. On June 11, 1737, the elector took part in the shooting of the Sebastianus riflemen - and became the rifle king . In 1760 Casanova arrives at the court and takes part in a masked ball of the elector.

His first architectural interest was in the Weinbergschlösschen, the " Vinea Domini ", south of Bonn. Commissioned by Joseph Clemens and built by the architect Guillaume d'Hauberat , Clemens August leases the castle and makes it one of his favorite places for entertainment and festive dining.

The proximity to the Kottenforst had long been a reason for choosing Bonn as the electoral residence: In 1549, Siegburg Abbey sold the basic rights to use the Kottenforst to the Archbishops of Cologne, who already had the right to hunt large game in the Kottenforst and built hunting castles in Poppelsdorf and Buschhoven had.

Around 1727, the Kottenforst was systematically surveyed for the first time under Clemens August von Bayern in order to create avenues for his parforce hunts . These mostly wide avenues were piled up dead straight and ditches were provided on both sides because of the wet subsoil. In 1730 Clemens August had the Schönwaldhaus forest service building built and later, from 1754 to 1756, the Herzogsfreude hunting lodge in Röttgen was built by the electoral builder Johann Heinrich Roth in the center of this system of avenues. The exact alignment of the paths in relation to the electoral palace and also to Schloss Brühl is remarkable .

At the end of 1741, Kurköln was on the side of Bavaria and France in the struggle for succession in Austria . French troops moved into the archbishopric for protection.

Then a construction period began: One of the most original creations of the early Rococo was the construction of Clemensruhe Castle in Poppelsdorf on the site of the old Poppelsdorf Castle ( 'Star Castle ' ) from the 16th century. In 1746, the electoral building manager, Count August Wilhelm Wolff Metternich, acquired the ground and construction of the 'Sterneburg' for the conversion to a rococo castle, which was carried out by Michael Leveilly and others. Joseph Clemens' bold plan to connect the two castles in one canal was never realized. His successors would build an imposing chestnut avenue on this axis, which still today connects the two palace buildings as an optical axis. However, it must also be noted that Clemens August's extensive construction work in Bonn, in Brühl and other places led to a high level of national debt in Kurköln.

An important construction site also opened up in 1746: the pilgrimage church and monastery on the Kreuzberg had suffered severely during the siege of 1689 and served as the headquarters of the English commander-in-chief, John Churchill, Duke of Marlborough . Elector Clemens August had the pilgrimage church restored and expanded by an extension to the choir of the church by 1751. He donated the Holy Stairs, the planning of which was implemented by the famous master builder Balthasar Neumann , in the style of the staircase in Augustusburg Castle in Brühl (built from 1740 to 1746).

In 1755, almost 60 years after the foundation stone was laid by the previous prince, construction work on the residential palace was completed, although the wing facing the Rhine remained a torso. Possibly related to this: In 1755, Clemens August separated from his director, Count August Wilhelm Wolff Metternich.

In the same year Clemens August had a ' Porcellain-Fabrick' set up in Katzenburg near Poppelsdorf Castle . Johann Jacob Kaisin and Ferdinand von Stockhausen were supposed to make porcelain for the court here . Porcelain was one of the elector's numerous costly passions. Since this did not succeed, the company was continued as a faience manufacture .

Regarding the reigns of Joseph Clemens and Clemens August, it must be noted that both electors developed Bonn as a center of European music. Numerous musicians were hired from all over Europe, especially from Italy and France. The composer Joseph Clemens dall 'Abaco was appointed director of court chamber music in 1738 . His successor was the composer Joseph Gottwald in 1752 . In 1760 Joseph Touchemoulin became court conductor. The bassist and singer Ludwig van Beethoven , the grandfather of the composer Ludwig van Beethoven, has been working in Bonn since 1733 .

Elector Clemens August died unexpectedly on February 6, 1761, during a trip to Munich near Ehrenbreitstein . Joyful as he was, he had not chosen a successor, but left behind an elaborate court, partly unfinished palace buildings and an enormous mountain of debt. On 6 April 1761 which elected cathedral chapter to Domdechanten Graf Maximilian Friedrich von Koenigsegg-Rothfels the new Elector and Archbishop. The almost 180-year-old Wittelsbach era in Kurköln came to an end.

Electoral Cologne residence city under Maximillian Franz (Habsburg)

Count Maximilian Friedrich von Königsegg-Rothenfels, who partially delegated the official business to Minister Kaspar Anton von Belderbusch, began to deal with the auction of the estate in order to restore the state finances to some extent. As sovereign, the count is prudent, economical, efficient and a little colorless. But even this sober sovereign still knows how to tie the musicians to Bonn and there were numerous opera performances. In 1778 the electoral court theater ( Bonn National Theater ) was founded. Plays by Lessing , Schiller and Shakespeare were staged by the director and playwright Gustav Friedrich Wilhelm Grossmann . During his reign, however, there were also catastrophes for Bonn and the people of Bonn: in 1771 there was a famine in Bonn and the country, in 1777 the castle burned and in 1784 Bonn suffered from the flooding of the Rhine.

The repeal of the Jesuit order by Pope Clement XIV gave the chance to reform the Jesuit high school in Bonngasse. In 1774 the grammar school was transformed into the 'Maxischen Akademie' . The academy is the nucleus of the later University in Bonn, which is officially founded on November 20, 1786. It quickly gained the reputation of an institution whose teachers sympathized with the ideas of the Enlightenment . The list of the Bonn Illuminati and the reading society founded in 1787 includes numerous other prominent citizens as well as numerous teachers and professors; including the musical teachers Ludwig van Beethoven , Christian Gottlob Neefe and Franz Anton Ries .

In 1780, Maximilian Friedrich von Königsegg-Rothenfels, was now 72 years old, it was time to look after the successor. The Austrian Maximillian Franz was therefore appointed coadjutor for Cologne and Münster (August 7, 1780). The sovereign died on April 15, 1784. His successor Maximilian Franz, who was to become the last elector, entered Bonn on April 27, 1784.

The reign of the Habsburg Maximilian Franz was to last about 10 years. He worked as a patron of the arts and sciences, appeared in a simple skirt and kept in close contact with his subjects. In 1789 Christian Gottlob Neefe wrote about the sovereign that he was one of "the most enlightened German princes".

Godesberg owes him the rise to a spa and bathing town towards the end of the residential epoch. Between 1790 and 1792 the elector had the Rédoute built near the mineral fountain as a ball and concert hall for visitors to the spa . In addition, a (Godesberger) court theater. The architect was Michael Leydel. Parks were created around the mineral fountain and a company was commissioned to use the healing power of the fountain ( 'Godesberger Wasser' ).

On November 2, 1792, in the calm before the storm (the aftermath of the French Revolution ), Ludwig van Beethoven left his hometown Bonn to continue his studies in Vienna.

End of Kurköln in Bonn and French occupation

As early as April 20, 1792, the French National Assembly in Paris had declared war on the (German) Reich in the course of the coalition wars. On December 22nd, the revolutionary troops invaded the Rhineland under the tricolor . The elector resigned for Munster . After the Battle of Aldenhoven (March 1, 1793), apparently a turning point, the Elector Maximilian Franz returned to Bonn on April 21, 1793.

On October 8, 1794, the French troops of the Northern Army under General Jean-Charles Pichegru entered Bonn. The elector had left for Dorsten a few days earlier . Maximillian Franz fled to Vienna and left his electorate, in a hopeless situation, to the revolutionary troops without a fight. Kurköln was history.

In the Peace of Lunéville in 1801, all areas on the left bank of the Rhine of Kurköln were ceded to Napoleonic France. The Rhine now formed the eastern border of France. Bonn and the associated canton belonged to the Département de Rhin-et-Moselle in the following years ; the capital of the department was Koblenz .

The French occupation brought serious changes for Bonn. With the end of the electoral era in the Rhineland, the time in which the city had held the function of a residence ended. Most of the members of the court and with them a large number of residents left the city with the elector. In addition, the still young university was closed. The population fell rapidly and citizens faced major economic problems in the years that followed. For the year 1809, an area of 333.3 hectares was designated for viticulture in the Bonn area, which shows the economic importance of Rhine wine .

The new legal system introduced by the French was of far-reaching importance. On May 1, 1798, the French government commissioner François Joseph Rudler issued an ordinance which ensured that the laws on civil status that came into force in France in 1792 also apply to the Rhenish department. Four years later, on April 8, 1802, the Organic Articles were promulgated, which meant freedom of worship and full civil rights for Protestants and Jews . On March 21, 1804, efforts to create a new legal system were crowned with the introduction of the Napoleonic Code .

On November 6, 1811, Emperor Napoleon I visited . Bonn for the second time, this time to examine the possibility of fortifying the city. On January 5, 1812, the first edition of the "Bonner Nachrichtens- und Anzeige-Blatt" appeared. At the beginning of 1814 the French had evacuated Bonn and on January 17, 1814 Prussian troops arrived in Bonn.

However, Prussia's presence in Bonn was initially ambivalent: the Prussian army entered Bonn with hussars and lancers, plus Cossacks and an East Prussian hunter battalion. To the annoyance of the Bonn residents, they behaved like victors in a conquered province. It is well known that contemporary Bonners always pointed out that they were not Prussians, but “ booty Prussians ”. The end of the French occupation was nevertheless a longed-for event for the population and the freedom movement. The Bonn writer Ernst Moritz Arndt had supported the national unity movement with various writings, including Der Rhein, Germany's river, but not Germany's border , in which he called for the German-speaking Rhineland to be replaced by France. In his honor, a memorial was set on the old customs in 1865, the inscription of which u. a. "The Rhine, Germany's river, but not Germany's border" reads.

Prussian Bonn

District town in the Prussian Rhine Province

As a result of the Congress of Vienna , Bonn fell de jure to Prussia in 1815 . Bonn became a district town in the administrative district of Cologne in the Rhine province . In general, the city developed enormously under Prussian rule. This was mainly due to the founding of the university and its popularity, also among the military, as a place of retirement and retirement. The revival of public life may also have been due to the arrival of Protestants in the middle of the “Catholic Rhineland”. After all, the deliberate favoritism by the House of Hohenzollern had an extremely favorable effect on urban development.

In 1818, today's Rheinische Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität Bonn was re-founded - as a counterpart to the also newly founded Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität Berlin (the Prussian re-establishment was expressly not a continuation of the first University of Bonn, which went down in 1794). It shaped the life of the city in the next decades. In political and social terms, the antagonism between the Catholic majority and the Protestant upper class was decisive until the end of the Empire .

March and revolution of 1848

During the pre- March period and especially after the Hambach Festival (1832), Bonn's students became politicized. They too were affected by the general suppression of freedom of the press, freedom of association and freedom of assembly during the Prussian reaction , but from 1832 onwards there were repeated clashes with the police.

After the February revolution in Paris in 1848 , the events calling for democratic reforms also tumbled in Bonn. Important protagonists from Bonn were Ernst Moritz Arndt , Friedrich Christoph Dahlmann and Gottfried Kinkel . On March 20, 1848, Kinkel spoke to the citizens of Bonn from the steps of the town hall under the black, red and gold flag. Since May 18, 1848, the German National Assembly , which also included seven professors from Bonn , met in the Paulskirche in Frankfurt am Main . In August 1848, Kinkel took over the editing of the “Bonner Zeitung”, which professed “social democracy”. The closest collaborator was the student Carl Schurz . Kinkel and Schurz founded the Democratic Association in Bonn with the aim of popular sovereignty and German unity. On November 17, 1848, Kinkel called up the Bonn vigilante group. There were tumults on November 18 and 19, 1848, which were ended under the pressure of a Prussian infantry battalion advancing on November 20, 1848. Between 1848 and 1852 all associations were dissolved, the actors arrested or driven into exile. Kinkel himself went into exile in London .

From 1844 Friedrich Wilhelm August Argelander , since 1837 professor for astronomy in Bonn, carried out the so-called Bonn survey at the Bonn observatory of the University of Bonn . It was carried out and published between 1846 and 1863 with the support of Adalbert Krüger and Eduard Schönfeld . The catalog and atlas contain 324,198 stars from the northern hemisphere with precise locations and brightnesses of celestial objects.

From February 15, 1844, a railway operated by the Bonn-Cölner Eisenbahn-Gesellschaft ran between Cologne and Bonn . The railway is extended to Koblenz in 1858. On October 1st, 1846, the Agricultural College for Rhenish Prussia was established (from 1861: Agricultural Academy Bonn-Poppelsdorf, from 1920 Agricultural University, from 1934: Agricultural Faculty of the University). The lectures began in the 1847 summer semester.

Bonn before the founding of the Empire

In 1850, Bonn received its own regional court as part of the new Prussian municipal ordinance of 1850. Around 1852 the city had around 20,000 inhabitants. In 1852, gas-powered street lighting was started, the nucleus of the Bonn municipal utilities . In the same year, on September 5, 1852, Hussar Regiment No. 7 , coming from West Prussia , moved into garrison in Bonn. On July 29, 1856, the composer Robert Schumann died in Endenich, after a two-year stay in the local sanatorium. He was buried in the old cemetery .

Bonn was part of a certain Rhine romanticism , as the following quote shows:

"Bonn is no longer in the heart of beauty, but it still belongs to the most beautiful section of the Rhine Valley, that Rhenish paradise, whose center we see the Siebengebirge."

On June 1, 1863, the "Bonn Citizens' Association" was founded, a meeting point for the Catholic, upper middle class, which determined the social and cultural life of the city in addition to the Protestant "reading and recreation society". Since Bonn and Beuel were not yet connected with a real bridge (so-called "flying bridge"), a steam ferry was used from July 2, 1863. In the 1860s, numerous student associations were founded and the relationship life determined the social and cultural life of the mostly male students and their elders, the so-called Philistines, including numerous lecturers and professors.

In 1865 the Arndt memorial was inaugurated on the Alter Zoll after Ernst Moritz Arndt died in Bonn in 1860 at the age of 90. In 1865 part of the population boycotted the celebrations for the 50th anniversary of the annexation of the Rhineland to Prussia. This happened out of opposition to the Prussian attitude in religious school questions. Quite a few citizens refer to themselves as “ booty Prussia ”, which was due to the Kulturkampf of that epoch. In 1868 the 50th anniversary celebrations of Bonn University took place. In 1866 Joseph Meyer, who came from Koblenz, founded a flag factory, which will later be called the " Bonner Flag Factory " and which still exists today.

The founding of the empire in 1871 brought Bonn some boom in the wake of the euphoria of the founding years . Since Bonn had become known in Prussia as a retirement home, numerous millionaires who had made a fortune through industrialization settled in Bonn with their magnificent villas. New schools and churches were built, and a water and gas works were built. The university also built new buildings, for example for the Chemical Institute (1864–67), Anatomy (1869–72) and the Physiological Institute (1875–78). In the southern part of the city, numerous representative houses of the middle and upper classes were built, which still shape the cityscape today.

Bourgeois, Prussian, Wilhelmine Bonn

The new Beethovenhalle was completed on December 17, 1870 and inaugurated in August 1871. From 1872 the Catholic " Deutsche Reichszeitung " appeared in Bonn. In 1872 the Behrendt bookstore was founded. A number of civic and veterans' associations emerged. In 1876 the restaurant "Hähnchen" opened, a popular meeting place for citizens, students, professors and garrison soldiers. In the same year the Soennecken-Verlag settled in Bonn. In 1877 the new main post office was opened in the Fürstenberg Palace on Münsterplatz .

In 1879, the new synagogue built between 1877 and 1878 on the banks of the Rhine, not far from today's Kennedy Rhine Bridge, was inaugurated according to plans by the architect Hermann Eduard Maertens. It was burned down in 1938 - a plaque on the bridge (north side) still reminds of it today.

On October 1, 1887, Bonn left the Bonn district in order to become an independent university town.

On June 7th, 1880 the railway line Bonn- Rheinbach - Euskirchen to the Voreifel was inaugurated. In the 1890s Godesberg, Dottendorf, Endenich, Kessenich and Poppelsdorf were incorporated. At the same time the fortifications were removed except for the old customs and only the star gate remained of the city gates.

From 1883 to 1885 a new station building (today's main station) was built. The main hall still suggests a pompous city gate. The building plot is in the lowest part of the city, an old, silted up arm of the Rhine. Around the train station there is still a muggy, hot climate in midsummer, which is why the vernacular speaks of the “Bonner Loch”.

On November 1, 1889, a new type of newspaper appeared for the first time, the “ General-Anzeiger ”. The publisher of the Bonner Zeitung, Hermann Neusser, dealt with the changes caused by the Kulturkampf . In connection with this, the publisher also founded a book printing company, which he combined under the umbrella of a stock corporation. The General-Anzeiger, subtitled “... for Bonn and the surrounding area”, was conceived as a daily advertising paper, highlighted local and regional reporting and was distributed free of charge. The new paper abstained from any political, social or religious partisanship ( editorial line ), in contrast to the Catholic-oriented " German Reichszeitung " published in Bonn .

From 1891 horse trams were set up for inner-city traffic. From 1893 a steam tram ran to Godesberg and Mehlem.

In 1898 the first massive Rhine bridge was built between Bonn and Beuel. It was inaugurated on December 17, 1898, after three years of construction. Apart from the Roman bridging of the Drusus, this was the first permanent connection between Bonn and the area on the right bank of the Rhine. Since, from Bonn's point of view, the people of Beuel initially did not contribute to the construction costs (4 million marks), then not enough, the bridge toll was levied until 1938 and on the Bonn side on the land pillar, the steel bridge built by the Gutehoffnungshütte , the Bonner Bridge Man ( "Bröckemännche") attached. The little bridge man shows his bare buttocks on the Beuel side, called "de schääl Sigg", and still exists today. From May 21, 1902, the first electric tram ran over this bridge between Bonn and Beuel.

In 1882, the provincial, insane, remedial and nursing home , today's LVR Clinic Bonn , was opened on Kaiser-Karl-Ring . In 1886 the Bonner Heimat- und Geschichtsverein (BHGV) was founded. In 1890 the "Provinzialmuseum" opened (today's Rheinisches Landesmuseum Bonn ).

In 1897 the Bonn garrison was expanded as part of the Prussian army reform . The 9th Rhenish Infantry Regiment No. 160 moves into quarters in the Ermekeil barracks in Bonn .

From 1898 the Rheinuferbahn ran to Cologne. At the same time, the foothills railway will be opened as a steam-powered narrow-gauge railway between Bonn and Cologne after six years of planning and construction. The railway, popularly known as " Fiery Elias ", ran until 1929. In 1905, the Bonn horse-drawn trams were taken over by the city and switched to electrical operation. Electric trams have been running to Mehlem, Königswinter and Siegburg since 1911/13. This essentially laid the network of today's local public transport.

As everywhere in the German Reich, the new century was celebrated in Bonn with balls on New Year's Eve and church services on New Year's Eve. On January 1, 1900, the royal hussars and the 160 infantry regiment marched in the courtyard garden in spring-like weather.

In 1902 a second synagogue was inaugurated in Poppelsdorf, and in 1903 a new synagogue in Beuel. Approx. In 1914 the Jewish community in Bonn had 1,200 members.

On October 1, 1907, Bonn received its first orchestra, led by Heinrich Sauer. The city orchestra is now called the " Orchester der Beethovenhalle Bonn ". The Beethoven-Haus association founded in 1889 also enriched Bonn's musical life. August Macke, who moved to Bonn with his parents at the age of four in 1901 , is one of Bonn's most important painters and is considered an exponent of the Expressionism he helped shape . The expressionist Hans Thuar also lived in Bonn from 1911 until the evacuation in World War II .

The period between 1900 and 1914 was generally characterized by the founding of numerous clubs, including some sports associations, such as the Bonn Football Club (1901) or the Bonner Swim Club 05 (BSV) in 1905. Around 30 sports clubs joined together in 1908 to form the “Association of Bonn Gymnastics and Sports Clubs " together. Numerous sports facilities were built during this time, including the Bonn Victoriabad from 1903–05. The Beueler Strandbad on the Rhine, the Rheinbadeanstalt, built in 1905, was very popular. This Rheinbadeanstalt was a floor-less wooden structure on pontoons and moored on the bank. The bath existed until 1967.

Art Nouveau was also reflected in the urban architecture : numerous Art Nouveau facades in the southern part of the city have been preserved. The Victoriabad, built in the Jugend style, fell victim to the bombs of World War II. The tram depot at Graurheindorfer Straße 157, built in 1905 according to the plans of the municipal civil engineering department, has been preserved. It consists of four hall facades with three gates each and is considered a prime example of Art Nouveau in industrial architecture.

For Bonn, the epoch is also known as the "Imperial Era". This was the expansion of the garrison, the special goodwill of the Hohenzollern over the city and the reputation of the university as " Prince University ," and " Prince-Universita t", a reputation that Bonn after 1843, as a preferred training location of the male Offspring of the Hohenzollern acquired. Both Kaiser Wilhelm II . himself and four of his sons studied in Bonn. The princes were given a spacious and comfortably furnished study room in the east wing of the university.

On June 1, 1904, after incorporation, Bonn already had 78,000 inhabitants. There were three different zones of the agglomeration: Bonn-Stadt was the core city, the later incorporated Beuel on the right bank of the Rhine had an industrial character and Godesberg was a rather dreamy bath. The population was over-aged, with the highest quota of "unemployed" after Wiesbaden , ie retirees and pensioners (nickname "Pensionerstadt") and, probably in connection with the university, had a high level of education. Godesberg had the somewhat derisive nickname " Pensionopolis ". Bonn consciously cultivated the image as an elegant residential town with magnificent villas (such as the Palais Schaumburg-Lippe ), the nimbus of well-known local personalities from culture, politics or science and as a charming travel destination. Extensive avenues, gardens and parks, "odorless and noise-free" industrial operations carefully selected by the city fathers, a lively club, music, theater and cultural life underlined this claim. The Wilhelmine Bonn also scored points from an economic point of view: at the turn of the century, Bonn was the fourth richest city in Prussia after Frankfurt am Main, Charlottenburg and Wiesbaden.

In 1912 the zoologist Alexander Koenig laid the foundation stone for the construction of a natural history museum (the shell was completed in 1914 according to the plans of the Royal Building Councilor G. Holland; it was not opened until 1934). In 1913, Wilhelm Stollfuß founded the Stollfuß publishing house in Bonn. In 1913, the Stadtsparkasse Bonn was rebuilt according to plans by the Cologne architect Peter Recht on today's Friedensplatz.

In 1913 Bonn had around 8,000 industrial employees. Half of these employees worked in the three largest industrial companies in Bonn: The Soennecken stationery factory , the Franz Anton Mehlem stoneware factory and art pottery and the Ludwig Wessel porcelain and stoneware factory .

Bonn from 1914 to 1919

On August 1, 1914, the garrison in Bonn was mobilized and cheering Bonners said goodbye to the generally surging enthusiasm for war with cheers, flowers and flags. Soon, in 1914, the first rationing measures were issued and appeals for donations were made. By September 20, 1914, the Bonners subscribed around 17.5 million Reichsmarks in war bonds .

In 1915 "bread books" were given out to the population, without which baked goods could no longer be given out. Meat-free days are introduced in November 1915, the second winter of the war. In the summer of 1917, six of the eight bells at the collegiate church were dismantled and handed over to the army administration. Joseph Goebbels left Bonn in March 1918 after studying here for two semesters.

Shortly before the end of the First World War , the city was hit by nine bombs from six British day bombers coming from Ochey in France on October 31, 1918 during an air raid originally planned for Cologne- Deutz and the industrial facilities there, killing 26 people and 56 injured.

On November 9, 1918, the republic was proclaimed in Berlin . The 1st World War was now over and the Kaiser abdicated. A total of 2,241 soldiers from Bonn-Stadt died in this war from 1914-18. For Bonn, Godesberg and Beuel together there were 2,783 fallen soldiers.

In the course of the November Revolution, in Bonn on November 9, 1918, in response to looting and gunfire in the city the day before, which was mainly caused by a group of armed sailors and soldiers who had arrived from Cologne, a workers', Citizens 'and soldiers' council as the highest authority for the city. This advice took over a. Administrative, welfare and police duties. A vigilante group emerged. The representatives covered a broad spectrum of society: center, liberals, social democrats and trade unions. The inclusion of the bourgeoisie, which occurred due to the local minority position of the workers in the general population, and its intensive cooperation with the city administration can be regarded as an exception for cities of this size. The council met 23 times, each with around 40 members, until it ceased its activities on December 11, 1918. According to administrative reports and chroniclers of the time, this council ensured that the revolution proceeded in an orderly manner despite all the excitement.

On November 16, 1918, the German troops returning from the western front began to move through Bonn. The demobilized field grays were greeted with flowers and cheers. The houses were flagged. A refreshment hall was opened for the soldiers on the grounds of the Chamber of Agriculture in Endeicher Allee.

On December 8, 1918, British occupation troops entered Bonn with an advance guard of 150 soldiers. The areas on the left bank of the Rhine of the German Empire were now occupied. As a result, Bonn briefly became the Canadian corps headquarters. At the end of January 1919, the Canadians were replaced by the British.

Bonn in the Weimar Republic

The consequences of the First World War did not leave Bonn unaffected. Between 1918 and 1939 the population rose only slowly from 91,000 to 100,000. The Allied occupation of the Rhineland from 1919 to 1930 also hit Bonn. The British occupiers stationed in Bonn since December 1918 were replaced by the French in February 1920. The French chief delegate of the High Inter Allied Commission, Gélin, Lieutenant Colonel de Boissy, the commissioner for the city of Bonn and General Leconte, commander of the 33rd French Army Corps, resided in Bonn. The occupation zone in the vicinity of Cologne, and thus also in Bonn, was evacuated with a one-year delay in January 1926 as a result of the Locarno treaties .

On January 20, 1919, the Bonn citizens elected the Weimar National Assembly for the first time . The strongest force in Bonn-Stadt is the German Center Party (21,748 votes), followed by the SPD (9,779 votes), the German Democratic Party (5,656 votes), the German National Party (4,058 votes), the German People's Party (2,395 votes) and the Independent Social Democratic Party (USPD) (74 votes).

In September 1919, the war kitchen in the university building ceased operations because parts of the university building were confiscated by the British occupation. In the same month the association "Studentenwohl" was founded. Professor Fritz Tillmann , the rector of the university, took over the management . The association was supported by the city of Bonn and citizens of Bonn. The war kitchen became a student kitchen. In October 1924 a newly built student residence with a cafeteria , burse , reading and social rooms was inaugurated. The tasks of the association "Studentenwohl" are continued today by the Studierendenwerk Bonn .

Immediately after the war the idea of separating the Rhineland from Prussia came up. The background was French security interests, which, however, were never supported by the US or the British. The Rhineland was to be detached from the Prussian state or given autonomy. At the invitation of Cologne's Lord Mayor Konrad Adenauer , all Rhenish members of the Weimar National Assembly met in Cologne in the winter of 1919. An important representative of the Rhenish separatists was the Bonn lawyer Hans-Adam Dorten . Around 1923 there was a Rhenish republic , which was demanded by the separatists and the party "Free Rhineland", but was ultimately foiled by the Prussian police in autumn 1923. The year 1923 was politically extremely troubled anyway due to the German October 1923 . The separatists who had fled the cities in the Rhineland were chased away in the "Separatist Battle of the Siebengebirge". Ultimately, the idea of a Rhenish Republic found too few supporters in the population during the economically difficult period of the Weimar Republic, even if the separatists could trust the historical skepticism of the Catholic population in the Rhineland towards Prussia. The ties to Prussia were ultimately too strong: Bonn councilors Eduard Spoelgen and Otto Meyer made this clear to the French in discussions with the Rhineland Commission in Paris.

At the same time, after the Ruhr uprising , the Ruhr was occupied by the French and Belgians. The people of Bonn had accompanied the uprising on the Ruhr with passive resistance - on January 15, 1923, citizens of Bonn demonstrated with a minute's silence - the French occupiers regard this as an affront. Railway officials, including the Bonn railway officials, had tried to divert trains and shut down stations to prevent the coal from reaching France and Belgium from the Ruhr area. 432 Bonn railway officials and work were convicted. The Mayor of Bonn, Johannes Falk, was brought before a French court martial in April 1923 (sentence: three years in prison and 3 million marks fine), but was expelled shortly afterwards, like other Bonn citizens, and was only able to return to Bonn in October 1924.

In the autumn of 1920, the Institute for Historical Regional Studies of the Rhineland was founded in Bonn and affiliated with the university. In 1925 Bonn celebrated the millennium that the Rhineland belonged to the German Reich (May 16-27, 1925) and in 1926 a celebration of liberation from the French occupation. On March 23, 1926, President Paul von Hindenburg visited the "liberated Bonn". He is the first person to sign the new "Golden Book of the City of Bonn".

On July 10, 1926, Godesberg received the addition "Bad" by decree of the Prussian Interior Minister.

In 1927 a new wholesale market hall is put into operation near the Ellerbahnhof. The main university building was expanded from 1926 to 1930. At the beginning of the 1929 summer semester, over 7,000 students were enrolled in Bonn.

Ultimately, however, the 1920s in Bonn were marked by inflation, an increase in welfare cases and political radicalization. However, the city of Bonn became almost debt-free in the wake of inflation.

From 1932 (construction period from 1929) the first German motorway connected Bonn with Cologne. It was inaugurated on August 6, 1932.

During the Weimar Republic , Bonn remained a stronghold of the Catholic German Center Party . At the beginning of the 1920s, however, the German People's Party also had successes and in some cases became the second strongest force in Bonn. Although the NSDAP achieved a significant increase in votes, despite measures to prevent and intimidate the other parties, it did not succeed in overtaking the center as the strongest party. Since the local elections in Bonn in autumn 1924, the increase in votes for the NSDAP became apparent. In July 1926 the NSDAP formed a local group in Bonn. On November 28, 1926, the chairman of the NSDAP, Adolf Hitler, spoke at a (non-public) meeting in the Beethovenhalle. Hitler is officially forbidden to speak. The NS university group, which has existed since 1928, is heavily involved in the political agitation. Young voters, students and small traders were among the important voters.

Mayor Johannes Falk was sentenced on August 23, 1930 to a fine of 100 marks for insulting. After a defamatory article against the city administration in the " Westdeutscher Beobachter ", a Nazi party newspaper, Falk described the publication as a " Revolverblatt " and said that it was written by criminals against the German people and only taken seriously by limited people. On January 24, 1931, Reichstag President Paul Löbe (SPD) spoke to the Bonners in the overcrowded Beethoven Hall and described the political and economic situation in Germany and in the world. He explained that the Nazis' fascism could not fight the economic crisis.

The elections for the 4th German Reichstag on May 20, 1928 resulted in losses for the Center Party in the Rhineland, including in Bonn. The left parties, the NSDAP and the German National People's Party (DNVP) received a boost in Bonn and in the Reich. In the state elections of April 1932, the NSDAP's share of the vote was just under 24%. In the parliamentary elections in March 1933 , the NSDAP in Bonn received 32% of the vote, which, however, was well below the proportion in the German Reich (43.9%).

Construction of the Rhineland Pedagogical Academy in Gronau began in the Weimar Republic in 1930 . After the war, the building would serve as an administrative and plenary building for the German Bundestag. The building was inaugurated on October 2, 1933, but the expansion continued until 1938. The building plans came from government master builder Martin Witte, who consistently adopted the design language of the Dessau Bauhaus . The architectural style therefore absolutely did not correspond to the ideas of the new rulers. But they only changed the title of the institution to "College for Teacher Training".

Bonn during the National Socialism

Bonn until the start of the war

The Center Party won 36% of the vote in the local elections on March 12, 1933, the NSDAP 34%, the SPD 10% and the KPD 7%. That did not prevent the National Socialists from taking power in Bonn. One day after the election, on March 13th, they hoisted the swastika flag over the town hall. On the evening of the same day, NSDAP man Ludwig Rickert was appointed "State Commissioner" by Hermann Göring after the incumbent Lord Mayor Franz Wilhelm Lürken was given a leave of absence . Everywhere in the Reich, including Bonn, leading city officials were replaced in the course of the " Gleichschaltung ". In June 1933, Rickert was also formally mayor. In August 1934, the vote on the law on the head of state in Bonn resulted in 18.6% no votes.

On May 13, 1934, the Alexander Koenig Zoological Research Institute and Museum was opened.

From 1933, violence by the SA was also used in Bonn, resulting in arrests (protective custody), professional bans, intimidation, propaganda marches and torchlight procession. Above all, however, the Jews suffered from the new conditions, were initially subject to defamation, and in April 1933 the first boycotts of Jewish businesses took place. Beginning with the Nuremberg Laws of 1935, expropriations took place and Jews were deported. In 1938 the Jews of Bonn were forced to pay a "property levy" of 1.5 million Reichsmarks. During the Reichskristallnacht on November 9 and 10, 1938, uniformed troops of the SA and SS came to the city and set fires in the synagogues of Bonn, Poppelsdorf, Bad Godesberg, Mehlem and Beuel. The supposedly spontaneous upsurges of popular anger were anti-Jewish smear campaigns ordered and organized by the NSDAP and SA. The acts of terrorism were also intended to induce Jews to leave voluntarily.

More than 1,000 Bonn residents, mostly citizens of the Jewish faith, were murdered during the Nazi era . About 8,000 people had to leave their hometown, were arrested or imprisoned in concentration camps . The Jewish community in Bonn had around 1,300 members in 1933; in 1939 there were only 464 people. In the course of the “ Final Solution to the Jewish Question ” in June 1941, they were initially transferred to the “For Eternal Adoration” monastery in Endich, which was evacuated by the Gestapo , and from there to the extermination camps . On January 26, 1942, the mathematician Felix Hausdorff took his own life, his wife and his sister-in-law, because he was to be assigned to the monastery. As far as is known, only 7 of those kidnapped Bonn survived the Holocaust .

Victims statistics after twelve years of Nazi dictatorship in Bonn:

| Group of people | Total pursued | killed by it |

|---|---|---|

| Jews | between 1600 and 1700 | about 770 |

| Forced sterilization and “ euthanasia ” victims |

about 4800 | about 380 |

| Sinti | about 100 | about 50 |

| Slave labor | about 10,000 | at least 8 |

A number of prominent Bonn citizens and their families were among the victims of the persecution; so the mathematician Felix Hausdorff and the geographer Alfred Philippson . In Bad Godesberg it was the chairman of the Center Party, Joseph Roth . The Bonn city councilor of the KPD , Otto Renois , was the first victim of the Nazi regime in April 1933. The fate of the Christian trade unionist Heinrich Körner , who was arrested again and again, was shot dead by a stray SS patrol in Berlin in 1945, two hours after the liberation from Plötzensee by Russian soldiers, was tragic .

For the university, too, the "synchronization" meant strong interventions in organization, content and personnel policy. Around 24% of the professors belonged to the NSDAP, but the proportion of National Socialists among the students was much higher, even though they did not constitute the majority in the General Student Committee (ASTA) in February 1933 . On May 10, 1933, a book burning “against the un-German spirit” took place on the market square, attended by numerous “folk-enthusiastic” students, representatives of the Stahlhelm , as well as professors Hans Neumann and Eugen Lüthgen.

There was quiet resistance from the two theological faculties and the religious communities. For the Catholics, Professor Wilhelm Neuss , worked out together with colleagues, published an illegal script as a counter-position to Alfred Rosenberg's The Myth of the 20th Century . The Protestant theologians, who were generally considered to be left-liberal by the National Socialists, were "transferred" numerous times. However, there was no exchange of a pastor in Bonn between 1933 and 1945.