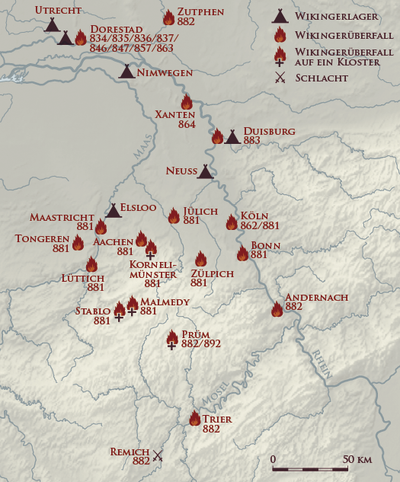

Viking raids in the Rhineland

The Viking raids into the Rhineland were part of the Viking incursions into the Frankish Empire and took place in the last decades of the 9th century. From the Rhineland, which can be seen as the nucleus of Franconian culture, the Franks had previously conquered almost all of Central Europe and established a great empire.

During these raids, the Vikings plundered the old Roman cities of Cologne, Bonn, Xanten, Trier and also the imperial city of Aachen, in which Charlemagne was buried and on whose throne in Aachen Cathedral the Franconian kings were crowned. In addition to these cities, numerous monasteries were also destroyed, and entire libraries were lost, in which collections of scriptures from several centuries had been stored. This shook the substance of the Frankish culture.

Similar robberies also affected the Scandinavian regions in which the Vikings originally settled, the British Isles , the Baltic States , Russia and the Mediterranean . Numerous residents of the affected regions were abducted into slavery .

The Rhineland

With Rheinland is not precisely defined areas referred to in the Middle and Lower Rhine. It is only referred to as such from 1798, when French revolutionary troops occupied this area. Previously, this region was mostly assigned to cities or counties by name (example Gelderland , Klever Land).

The area known today as the Rhineland begins roughly at the point where the Moselle flows into the Rhine and ends at Emmerich , where the Rhine splits into the Lek and the Waal to form a delta . In the east the Rhineland ends in the immediate vicinity of the Rhine; it is bounded by low mountain ranges such as the Siebengebirge or the Bergisches Land . The border to the west is unclear, in common parlance today's border line to the Netherlands has become naturalized, i.e. east of the Meuse. Since today's state of Rhineland-Palatinate lies south of the Moselle, the Eifel low mountain range bordering the Moselle to the north is mostly named as belonging to the Rhineland. Areas south of the Moselle such as the Hunsrück are also considered to be part of the Rhineland.

The Rhineland in the Carolingian era

The heartland of the Carolingians was mostly in areas that belong to the Rhineland. As a result, important places of Carolingian culture are in the Rhineland. Particularly noteworthy are the city of Aachen , in which Charlemagne had his imperial palace built, but also the Benedictine abbey in Prüm . The latter mainly because of its scriptorium with an attached library . The old Roman cities of Trier , Cologne , Xanten and Bonn were also in the Rhineland and were used by the Franks as trading centers and bishoprics . The Frankish empire was divided into three kingdoms in 843. Most of the areas of the Rhineland fell under the rule of Lothar I , which was called Lorraine . It was a middle empire that ran from the North Sea to the Mediterranean, East and West Franconia had no border contact. After this division of the empire, power struggles with a civil war-like structure broke out in almost all areas of the former empire , and the Rhineland was also affected. When Lothar I died in 855 without heir to the throne, the power struggles intensified. In the Treaty of Meersen , the Rhineland was assigned to Eastern Franconia in 870 . Ten years later, in the Treaty of Ribemont, the boundaries were defined more precisely. The adjacent map shows the result.

Vikings and Franks

After the defeat of the Saxons (772–804), the empire of Charlemagne expanded to the mouth of the Elbe and beyond. At this point at the latest, the first contacts with the Vikings, who, like the Saxons, worshiped a pantheon of gods , will have taken place.

The contacts were often of a warlike nature, but the Frisian Islands were affected as well as the Frisian mainland. To ward off the attacks, Charlemagne set up a mark on the northern border of his empire , the name of today's state of Denmark is derived from it. Despite the war-like conditions on the northern border, some Vikings hired themselves out as mercenaries on Franconian campaigns . Very few were baptized because the religion of the Vikings, unlike Christianity, contained a code of honor for warriors:

According to the legend, the prepared war god Odin , from the race of gods of the Aesir in the fight for the world and its continued existence before. He sent his messengers, the Valkyries , to escort only the bravest warriors who had fallen in battle to Valhalla . The warriors gathered there, called Einherjer , practiced their art of war during the day. In the evening, after her wounds had healed, the army of the dead moved together into Odin's hall, where a full drinking horn and a good meal always awaited them. For this reason, Vikings sometimes fought very daringly.

One of the first Viking kings to be baptized was Harald Klak , who became a vassal of King Ludwig in Ingelheim am Rhein in 826 AD and was baptized with his wife and son in Mainz.

During this time warlike Vikings penetrated the Franconian Empire with their ships over river systems that flowed into the North Sea and the Atlantic . Areas on the Seine , the Netherlands and Belgium were particularly affected by such raids . Previously, the Vikings went on a robbery voyage in England ( Lindisfarne , 793) and Ireland ( Dublin , 795). The first major attack by Vikings in the Franconian Empire was recorded in 820; the region of the Seine estuary was affected, and other Vikings presumably invaded Flanders at the same time. In 845 Paris was attacked for the first time with about 700 longships across the Seine. The Parisians bought 7,000 pounds of silver to withdraw the besiegers. Up to the year 926 thirteen such payments are documented in the Franconian Empire. The mouth of the Elbe and Hamburg , which was already fortified at that time , were also ravaged by Danish warriors in 845.

Initially, the attacks were like raids, and the Vikings withdrew to their homeland after successful raids. In the 860s, they changed their approach and established permanent locations in the Franconian Empire , from where they coordinated their raids, and occasionally wintered in their fortified army camps . The Rhineland and thus the heart of the Franconian Empire were seldom affected at the time.

The Vikings did not form a closed unit, they were a warlike people, small wars between Viking tribes were frequent, united large-scale attacks were always preceded by targeted diplomatic negotiations. Since the Vikings could only be expelled from the occupied territories with high losses, attempts were occasionally made to involve their leaders in the empire through rich gifts and fiefs . As a rule, these Viking leaders had to be baptized beforehand, as the Frankish kingdom was viewed by the Frankish nobility as given by God and therefore there were no thrones for highly aristocratic unbelievers.

The raids into the Rhineland in 862 and 864

Between 834 and 863 the Vikings devastated the trading hub Dorestad on the Lek eight times , which competed with the Danish Haithabu. In 862 Vikings rowed up the Rhine for the first time with warlike intent and sacked Cologne. In 863 the Norsemen conquered Utrecht and Nijmegen and set up permanent winter camps in both cities. Dorestad was completely destroyed during the campaign. In 864 they embarked on a second campaign in the Lower Rhine region and attacked and plundered the city of Xanten , founded by the Romans .

Trade and shipping on the Rhine between 864 and 881

The Franks were not real seafarers - there were indeed types of ship (Utrecht ship) which, in good weather, were suitable for coastal shipping; Since no wreckage has yet been found in the North Sea, coastal shipping will, however, have only rarely been operated, if at all. There were different types of construction for boats. Either mighty trees were hollowed out or raft-like boats were built together. Both types of boats were difficult to maneuver and were used to transport heavy goods such as stones. Ruinous Roman buildings near the Rhine were often used as quarries, but there were also quarries in the adjacent low mountain ranges. Down the Rhine these boats drifted with the current, upstream the boats were pulled by horses or oxen ( called towing ).

The main building material in the Frankish Empire was wood, felled logs were tied together and rafted downriver to the trading markets, other goods and travelers were also transported on the sometimes very long and wide rafts.

When the Vikings settled on the banks of the Rhine delta, they had a competitive advantage as traders, because thanks to their excellent shipbuilding technology , strong currents such as those of the Rhine could be overcome, so they were able to ship goods quickly. As a result, trade in the Rhineland flourished during that time . Since the Vikings also settled in Ireland, England and Russia at the same time, the commodity expanded to include products from and beyond even more distant regions.

Raids in winter 881/882

The situation changed when the so-called Great Pagan Army in 878 near Edington in south-west England suffered a severe defeat by the troops of King Alfred the Great (reign 871-899). The defeated Vikings then set off to continental Europe and relocated their raids to the coastal region of the English Channel , northern France and Flanders . On August 3, 881, King Ludwig III of West Franconia also triumphed . with his army over the Normans at Saucourt-en-Vimeu in central France.

The Vikings then turned their aggressiveness eastwards towards the Rhineland. Charles III held at that time because of his imperial coronation in Italy , which in February 12, 881 Rome took place. As a celebration he was accompanied by numerous armored riders , and so many of the most defensive warriors were not available to defend their homeland in the winter of 881.

Despite the invasion of the Great Army in 878 in West Franconia, no defensive measures seem to have been taken in the East Franconian Rhineland, because the walls of individual cities were only strengthened when the Vikings were almost at the gates . Because of this and because of the imperial coronation of Charles III. In Rome , the Rhenish population was almost defenseless against the Viking attack and escape was the best alternative that promised to save life and goods. Often entire villages and monasteries were left to the Vikings without a fight.

The raids in the Rhine-Meuse area

At the end of 881, Vikings who were wintering in Flanders set out on a campaign to neighboring lands. They raided numerous villages in the area around the Meuse and burned the cities of Liège , Maastricht and Tongeren to the ground.

In December 881, Vikings of this group sailed up the Rhine on at least three ships under their leader Gottfried (or Godefried). In doing so, they looted towns and cities or extorted money from their inhabitants ( pillage ).

The cities of Cologne , Bonn , Neuss , Jülich and Andernach were particularly hard hit . On their first visit in January 882, Cologne, after tough negotiations, paid a large amount of money in silver for their withdrawal (see also Danegeld ). On their return trip, the same group again demanded the payment of a sum of money, which the squeezed out Cologne residents could no longer afford. The city was then burned down.

The Norsemen, who presumably came from Denmark, might also have horses on their Viking ships. In any case, they were very mobile, and they could fall back on the old Roman roads of the Rhineland on the left bank of the Rhine. Following this road system, the Vikings turned west and plundered via Zülpich to Aachen .

The raids on the cultural centers in the Aachen area

When they stormed the imperial city, the conquerors, presumably with a strategically oriented calculation on humiliation , converted the Aachen Marienkirche (today cathedral), the burial place of Charlemagne , into horse stables. After these desecrations, they set the imperial palace and the thermal baths on fire. At the end of December 881 they plundered the Kornelimünster monastery, not far from Aachen, and the Stablo and Malmedy monasteries in the Ardennes .

The first attack on the Prüm Abbey

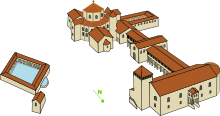

On January 6, 882, Epiphany , a Vikings division, which according to reports comprised around 300 warriors, attacked the largest Franconian abbey of Prüm in the Eifel . Emperor Lothar I , who died here in 855 , was buried in the abbey church . A hospital was attached to the monastery as well as an important monastery school in which the offspring of the Franconian aristocracy were educated. The abbey also housed one of the most extensive libraries in the empire with an associated scriptorium . In addition to Aachen, Prüm was the cultural center of the Franconian Empire. The monastery had extensive possessions, over a hundred churches were under its administration, the land ownership stretched far into the Netherlands, the forests along the Moselle also belonged to the monastery.

A crowd of farmers from the area opposed the attackers and were completely wiped out. The Vikings then set fire to all the buildings in the monastery. The abbey burned to the ground, as there was no one left who could have fought the fire (Regino von Prüm, 882). One of the greatest treasures of the monastery was one of the most precious relics of the Christian West , the sandals of Christ , which could be brought to safety before the onslaught of the Vikings. Of the manuscript collection, previously praised by chroniclers, only about a tenth of the holdings could be removed before the approaching Vikings, the entire remainder fell victim to the flames.

The Moselle Raid 882

The East Franconian King Ludwig III. raised an army and rushed to the aid of the Rhinelanders. On January 20th, the king died unexpectedly in Frankfurt am Main , whereupon the army he led against the Vikings dissolved. The Vikings then moved further up the Rhine. In the course of February and March 882 they stole and murdered as far as Koblenz , which was able to resist thanks to the good fortifications from Roman times. The districts in front of the walls were devastated. At the same time, the ruined Roman walls in Mainz were rushed back in place and the citizens of Mainz began digging a ditch around the city. The Vikings did not move from Koblenz in the direction of Mainz, but turned up the Moselle and reached the Trier area during Easter week.

During Holy Week 882, the Nordic warriors attacked and destroyed the monasteries, churches and farms located extra muros in Trier . The St. Maximin , St. Martin and St. Symphorian monasteries north of the ancient city wall were destroyed, although the latter was never rebuilt later. The St. Paulin Monastery , however, was spared.

On Maundy Thursday , April 5, 882, they took the city themselves. After a few days of rest, the Vikings plundered Trier on Easter Sunday . Among other things, the Trier Cathedral was affected. Regino von Prüm reports of numerous victims among the population, but Archbishop Bertolf von Trier managed to escape to Metz with a few followers . Then some of the Vikings moved with the booty down the Moselle towards Koblenz, while the rest moved towards Metz.

The Vikings advancing on Metz were captured on April 11, 882 in the battle of Remich by an army under the leadership of the Metz bishop Wala , the Archbishop of Trier Bertolf and the Count Adalhard II of Metz . The Vikings won this battle again, in addition to numerous armored riders and farmers, Bishop Wala also fell on the battlefield. The fierce resistance with the accompanying losses of their own caused the Vikings to turn back, and they moved north through the Eifel towards their army camp.

Ascloha armistice in spring 882

After his return from Italy, Emperor Karl III. held a Reichstag in Worms in May 882 , bringing together a large army in which Franks , Bavaria , Swabians , Thuringians , Saxons , Frisians and Lombards were represented. The army moved in front of the fortified Viking camp, which is named Ascloha ( Asselt ) in a source ( Annales Fuldenses 882). In another contemporary source, however, Haslon is mentioned as the place of negotiation , which is often equated with Elsloo on the Maas ( Regino von Prüm , Chronica 882, mentioned by name in the entry for the year 881).

Charles III besieged the Vikings with his army from a safe distance and began negotiations with the besieged after twelve days. The result of the negotiations was a withdrawal of the intruders bought with church property. On the condition that the Viking leader Gottfried was baptized , Friesland (Netherlands) was also transferred to him as a fief . The peace agreement was also sealed by a wedding with a Franconian princess . The princess named Gisla (Gisela) is said to have been a daughter of King Lothar II . The Vikings, who remained behind in Ascloha under the leadership of Sigfrid, were initially deterred from further robberies by considerable monetary payments.

The summer of 882

As early as the summer of 882, Gottfried returned with an army reinforced from home for a second raid into the Rhineland and devastated Cologne, Bonn and Andernach. In the vicinity of Andernach, numerous churches and monasteries were looted and set on fire.

Also at the IJssel located Zutphen and the nearby trading center Deventer was during this campaign sacked. Before Mainz, the Vikings were repulsed by an army led by Count Heinrich von Babenberg and the Archbishop of Mainz Liutbert (episcopate 863-889), and they probably only pillaged Cologne afterwards.

The fall of 883

The news of Gottfried's successes in the Rhineland and his rule in Friesland attracted more Vikings from Denmark. In the autumn of 883 they landed in Friesland, rowed up the Rhine with Gottfried's consent and moved into a permanent camp near Duisburg. They again devastated numerous towns that had just been rebuilt. The Cologne residents had reinforced their walls first and were therefore spared this time. When the Vikings passed, Cologne's churches and monasteries were still in ruins .

The Vikings withdrew from the Middle Rhine that year and settled permanently on the Lower Rhine . They occupied Xanten as well as Duisburg and from there undertook smaller raids in the area, especially the area around Xanten and the Ruhr area .

Franconian campaign against the Vikings 884

In 884, a troop formation led by Count Heinrich von Babenberg succeeded in recapturing Duisburg, and the Vikings withdrew from the rest of the Lower Rhine area in return for payment.

Hugo's conspiracy with the Vikings in 885

At the beginning of 885, Hugo , the only son of King Lothar II of Lotharingia from his second marriage to Waldrada , which was not recognized by the church, decided to regain his father's kingdom with the help of his brother-in-law Gottfried . He secretly urged Gottfried to strengthen his army with more Vikings from Denmark, and in case of victory promised him half of the land he had won. However, Gottfried did not wait and sent the Frisian Counts Gerulf and Gardulf as ambassadors to Emperor Karl III while numerous Vikings were pouring together at the mouth of the Rhine . As a reward for his loyalty and the protection of the borders of Koblenz , Andernach and Sinzig as well as other crown estates with vineyards on the Middle Rhine.

Charles III found out about the plans of the conspirators, possibly through Count Gerulf. On Heinrich von Babenberg's advice , he decided to lure the Vikings into an ambush and sent the ambassadors back with the news that he himself would send a messenger to Friesland with an appropriate answer to Gottfried's demands.

Heinrich von Babenberg first let his followers move secretly and in small groups through Saxony to the meeting point he had designated in Friesland. He himself traveled to Cologne to see Archbishop Willibert , who accompanied him on his journey down the Rhine. In the course of May 885 they arrived in the Betuwe , a landscape in Friesland surrounded by the two arms of the Rhine. Gottfried went to meet the Franks and they met in Herwen .

During the negotiations, Heinrich arranged for the archbishop to summon Gottfried's wife Gisela to the Franconian camp under a pretext in order to withdraw her from the threatened vengeance of the Vikings. Heinrich himself was negotiating in the meantime in the matter of the Saxon Count Eberhard, whose possessions had been plundered by Gottfried. When there was an argument, Gottfried von Eberhard was knocked down and murdered by Heinrich's entourage. Then all the other Vikings who were in the Betuwe, including their leader Sigfried, were killed. A few days later, Hugo was also lured to Gondreville, captured there, blinded and taken to Prüm Abbey , where he spent the rest of his life.

During the siege of Paris in 886, Heinrich von Babenberg fell into a pitfall set by the Vikings while riding near the city and was slain by his enemies there.

After Gottfried and Sigfried's death, the Rhineland was spared from incursions by the Vikings for a few years.

The spring raid in 892

In 891 the Vikings suffered a severe defeat against the Eastern Frankish king and later Emperor Arnulf of Carinthia near Leuven in Belgium and the defeated had to withdraw completely from Brabant . When the scattered Vikings had gathered south of the Meuse again, they undertook a campaign in the Moselle valley in 892 .

In February 892 they reached Trier and plundered the old Roman city again. Then they moved downstream and then down the Rhine to Bonn. At Lannesdorf they faced a numerically superior contingent of the local population. Due to the devastating defeat at Löwen, the fighting morale of the Vikings was not pronounced in the face of an overwhelming power, so they shied away from the fight and marched westward through the Eifel to the monastery of Prüm. As ten years before, they devastated the monastery and town, killed and kidnapped numerous residents, only the abbot of the monastery and a few monks were able to flee (from the Chronicle of Regino von Prüm , ad a. 892).

The fighting strength of the Vikings was permanently weakened after the Battle of Lions. They withdrew to Danish-occupied areas in Britain ( Danelag ) and from there only undertook occasional raids, but these only affected the European coasts - they no longer penetrated into the heart of the Franconian Empire.

Details on the Viking raids in the Rhineland

Viking clothing, armament and fighting style

The Vikings had a preference for colorful clothing. They mainly acquired the fabrics for this during their raids. But these fabrics also came to their Nordic homeland as commercial goods. Men wore a belted tunic with wool pants underneath. A shoulder coat and a cap provide protection against wind and weather. Wealthy Vikings trimmed their clothing with colorful braids or furs. The women wore long dresses, depending on the booth, more or less richly decorated with pieces of jewelry. Silver jewelry was preferred.

The life expectancy of the Viking warriors was not very high, serious wounds were usually fatal from infections. The majority of the warriors will have been between 20 and 30 years old, but young people also took part in the raids. Viking women only took up arms when their settlements were attacked.

Iron was a rare and expensive commodity, so the Vikings used it sparingly and effectively in the manufacture of their weapons. Most Vikings fought with axes or battle axes for this reason . The ax was also a tool that I used every day and was therefore carried almost always close at hand on the belt. The Vikings mostly used arrows and spears as long-range weapons. Rare were catapults or throwing stones used in long-range combat, the latter foremost in combat on the high seas, to ward or in the conquest of other vessels.

Swords were popular but rare and mostly only in the hands of very wealthy Vikings. Brightly painted round shields and helmets served as armor , but padded armor and leather armor were also worn. Archers wore no armor because of the necessary mobility and were mortally wounded very quickly if they got into close combat. As a rule, in the Viking Age there was no real order of battle, that is, those who were ready to fight met each other, the warriors stormed haphazardly into the opposing ranks and then fought the battle face-to-face.

Chain mail or scale armor were sought-after, very cost-intensive commodities. Only wealthy Vikings could afford them. Heavy armor and swords were therefore worth striving for and the infantry did not shy away from attacking Frankish armored riders. In contrast to the Franks, the Vikings did not fight from horses during the Rhenish campaigns, they only used them for riding and then fought as infantrymen . Most of the time, the Vikings attacked on their raids in smaller groups of a maximum of a few hundred warriors, it is assumed that the warriors lived on looted property that the amount of the expected booty determined the size of the troops.

Often the Vikings reached the places they wanted to raid on ships. The ships could then also act as an escape route if opponents proved to be superior. This type of warfare was unknown in Northern Europe until the Viking Age, so the port cities were usually only fortified on the land side and the first raids came as a surprise to the population of these cities. Only then were the ports fortified.

Many of the Viking swords found have Frankish blades and Nordic handles ; whether they were negotiated or captured is unclear. But not only the Franks could forge long swords, there are also swords made by Vikings. Highest quality swords are marked with the word Ulfberht , it is assumed that it is the name of a blacksmith or a blacksmith , but a magical meaning cannot be excluded. 40 swords drawn in this way have now been unearthed; the southernmost finds were in the Balkans .

Price ratio of weapons and armaments to other trade goods

- A knife had the equivalent of 3 grams of silver, for which 30 chickens could have been bought.

- A short sword or stirrup weighed 126 grams of silver, a price that could be obtained for 42 kg of grain.

- A shield and a lance could be purchased for 137 grams of silver, the equivalent of a cow.

- You could get a helmet for 410 grams of silver; three oxen had the same value.

- A long sword with a scabbard cost 478 grams of silver, which is what you could buy a horse for in Northern and Western Europe.

- The coveted chain mail cost 820 grams of silver, which was the equivalent of a female slave and two slaves or 28 pigs.

Temporal overview

The following overview shows some raids in a historical context in chronological order. Events that affect the Rhineland are marked in bold :

| time | Region, country | Remarks |

|---|---|---|

| 793 | Lindisfarne , England | Assault on a monastery |

| 795 | Dublin , Ireland | The raids on the city begin |

| 800 | Rome , Italy | Charlemagne becomes Emperor crowned |

| 814 | Aachen , Germany | † Charlemagne, burial in Aachen Cathedral |

| 820 | Flanders , Netherlands | Raids on the region |

| 820 | Seine estuary , France | Raids on the region |

| 834 | Continental Europe | The annual raids begin |

| 834 | Dorestad , Netherlands | First of a total of eight raids |

| 835 | England | The annual raids begin |

| 837 | Domburg , Netherlands | plunder |

| 842 | Quentovic , France | plunder |

| 843 | Nantes , France | Looting by the Loire Normans |

| 843 | Verdun , France | Treaty of Verdun , division of the empire under Charlemagne's three grandchildren |

| 844 | Seville , Spain | plunder |

| 844 | Gijón , Spain; Garonne Valley , France | plunder |

| 845 | Paris, France | The raids on the city begin, Paris pays first Danegeld (7,000 pounds silver) |

| 845 | Hamburg , Germany | Attack on the city and the surrounding area |

| 855 | Prüm Abbey , Germany | † King Lothar I, burial in the abbey church |

| 857 | Utrecht , Netherlands | plunder |

| 857 | Paris, France | plunder |

| 859-862 | Cities in the Mediterranean | Mainly affected Spain |

| 860 | Constantinople , Turkey | plunder |

| 860 | Iceland | Norwegian seafarers discover Iceland and colonize the island |

| 861 | Paris, France | plunder |

| 862 | Cologne , Germany | plunder |

| 863 | Dorestad, Utrecht, Nijmegen | Last of eight raids on Dorestad, complete destruction of the city, establishment of permanent army camps in the Netherlands |

| 864 | Xanten , Germany | plunder |

| 865-873 | The great army conquers England | Establishment of permanent locations ( Danelag ) |

| 865 | England | First payment of Danegeld in England |

| 866 | York , England | plunder |

| 878 ⚔ | Edington , England | Battle, the Great Heathen Army will by an army under Alfred the Great defeated |

| 878-892 | The Great Army devastated parts of the Frankish Empire | Establishment of permanent locations in the Netherlands and Belgium |

| 881 ⚔ | Summer: Saucourt-en-Vimeu , France | Battle, the army of Lothar III. beats the Vikings |

| 881 | Winter: Maastricht , Liège , Tongeren a . a. | Looting in the Netherlands and Belgium |

| 881 | Winter: Zülpich , Jülich , Neuss , Aachen a . a. | Looting in Germany |

| 882 | Russia | The northern and southern Varangian empires ( Novgorod and Kiev ) are united to form the Kiev Empire |

| 882 ⚔ | Prüm , Bonn , Andernach , Trier , Cologne , Deventer , Zutphen | Looting in Germany and the Netherlands, Battle of Remich |

| 883 | Duisburg , Xanten | Conquests and establishment of permanent army camps in Germany |

| 884 | Duisburg , Xanten | Heinrich von Babenberg conquered by Frankish warriors to Niederrhein back |

| 885 | Another incursion into the Rhineland | The Vikings are lured into an ambush, their leaders Gottfried and Sigfrid are killed |

| 886 | Paris, France | During the siege of Paris, Heinrich von Babenberg falls into a pit trap and is slain by the Vikings |

| 891 ⚔ | Leuven , Belgium | Battle, the later Emperor Arnulf of Carinthia defeats the Vikings |

| 892 | Trier , Prüm | Last campaign in the Rhineland, devastation and looting |

| 892 | Continental Europe | Retreat of the Vikings to England and Denmark |

| 911 | Normandy | The Viking King Rollo receives Normandy as a fief from the King of West Franconia |

| 917 | Dublin, Ireland | plunder |

| 985-986 | Greenland | Erik the Red begins taking land that has not been iced over |

| around 1000 | America | Leif Eriksson discovers and settles in Newfoundland |

| 1013 | England | The Danish King Sven conquers England |

| 1061-91 | Sicily | Norman warriors conquer Sicily |

| 1066 | England | Duke William the Conqueror of Normandy conquers England ( end of the Viking Age ) |

literature

- Peter Fuchs (Hrsg.): Chronicle of the history of the city of Cologne. Volume 1, Greven Verlag, Cologne 1990, ISBN 3-7743-0259-6 .

- Peter H. Sawyer: Kings and Vikings. Scandinavia and Europe AD 700-1100. Routledge, London / New York 1983, ISBN 0-415-04590-8 .

- Rudolf Simek : Vikings on the Rhine. Recent Research on Early Medieval Relations between the Rhinelands and Scandinavia. (= Studia Medievalia Septentriolia (SMS) 11) Fassbaender, Vienna 2004, ISBN 978-3-900538-83-5 .

- Walther Vogel : The Normans and the Franconian Empire up to the founding of Normandy (= Heidelberg Treatises on Middle and Modern History. Volume 14). Winter, Heidelberg 1906.

- Annemarieke Willemsen (Ed.): Vikings on the Rhine. 800-1000. Vikingeskibshallen (Roskilde), Rheinisches Landesmuseum Bonn , Centraal Museum (Utrecht) , Utrecht 2004, ISBN 90-5983-009-1 .

- Johann Hildebrand Withof, Albrecht Blank (ed.): The chronicle of the city of Duisburg. From the beginning up to the year 1742. Compiled from the Duisburg intelligence slips and annotated. Books on Demand, Norderstedt 2008, ISBN 978-3-8370-2530-9 online at Google Books .

- Eugen Ewig : The Trier region in the Merovingian and Carolingian empires. In: History of the Trier Land (= series of publications on Trier regional history and folklore. Volume 10). Working group for regional history and folklore of the Trier area, Trier 1964, pp. 222–302.

- Burkhard Apsner: The high and late Carolingian times (9th and early 10th centuries). In: Heinz Heinen , Hans Hubert Anton , Winfried Weber (eds.): History of the Diocese of Trier. Volume 1. In the upheaval of cultures. Late antiquity and the Middle Ages (= publications of the Trier diocese archives. Volume 38). Paulinus, Trier 2003, pp. 255–284.

Web links

- Jennifer Striewski: Vikings on the Middle Rhine. Rhenish History Portal, February 25, 2013, accessed on February 18, 2014 .

Remarks

- ^ A. Willemsen: Vikings on the Rhine. 800-1000 . Pp. 132, 156-157.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Jennifer Striewski: Vikings on the Middle Rhine.

- ↑ Edmund Mudrak : The sagas of the Germanic peoples. Nordic gods and heroic sagas . Ensslin & Laiblin Verlag, Reutlingen 1961, p. 30-32 .

- ↑ a b A. Willemsen: Vikings on the Rhine. 800-1000 . Pp. 155-157.

- ↑ Thorsten Capelle: Not only night and fog actions. In: Ulrich Löber (Ed.): The Vikings. Accompanying publication to the special exhibition "The Vikings" of the Landesmuseum Koblenz and the Statens Historiska Museum Stockholm. Koblenz 1998, pp. 87-94, here p. 88.

- ^ A. Willemsen: Vikings on the Rhine. 800-1000. P. 119.

- ↑ A.Willemsen: Vikings on the Rhine. 800-1000. P. 62.

- ↑ A.Willemsen: Vikings on the Rhine. 800-1000. Pp. 55-61.

- ^ A. Willemsen: Vikings on the Rhine. 800-1000. Pp. 64-71.

- ^ A. Willemsen: Vikings on the Rhine. 800-1000 . P. 2.

- ^ P. Fuchs: Chronicle of the history of the city of Cologne. Pp. 89-90.

- ↑ a b c A. Willemsen: Vikings on the Rhine. 800-1000 . P. 109.

- ^ Gabriele B. Clemens , Lukas Clemens : History of the city of Trier. Beck, Munich 2007, ISBN 978-3-406-55618-0 , pp. 70-71.

- ↑ As in Prüm, the attack took place on a major public holiday. Since it was the highest Christian holiday and calm only returned after the conquest, it can be assumed that the waiting and the subsequent devastation were carried out purposefully.

- ↑ E. Ewig: The Trier Land in the Merovingian and Carolingian Empire . Pp. 284-286.

- ↑ B. Apsner: The high and late Carolingian times (9th and early 10th centuries). Pp. 273-274.

- ↑ For identification cf. also The Annals of Fulda. Edited and translated by Timothy Reuter. Manchester / New York 1992, p. 92, note 7.

- ^ A. Willemsen: Vikings on the Rhine. 800-1000 . P. 164.

- ^ A. Willemsen: Vikings on the Rhine. 800-1000 . Pp. 132-136.

- ^ W. Vogel: The Normans and the Franconian Empire up to the founding of Normandy. P. 300.

- ^ A. Willemsen: Vikings on the Rhine. 800-1000 . P. 9.

- ^ JH Withof, A. Blank: Chronicle of the city of Duisburg . P. 118 ( online ).

- ^ W. Vogel: The Normans and the Franconian Empire up to the founding of Normandy. Pp. 303-306.

- ↑ RI I n 1701b. In: Regesta Imperii Online, accessed March 1, 2014.

- ^ P. Fuchs: Chronicle of the history of the city of Cologne . P. 91.

- ↑ a b c d e A. Willemsen: Vikings on the Rhine. 800-1000. Pp. 122-125.

- ^ A. Willemsen: Vikings on the Rhine. 800-1000. P. 144.

- ↑ edited and expanded after A. Willemsen: Wikinger am Rhein. 800-1000. P. 119.