Viking ship

Viking ship is the name for the type of ship that was mainly used during the Viking Age (800–1100) in Northern Europe, but was also built and used after the Viking Age. The ships are divided into long ships , knorr and smaller ships according to their size and function .

The first archaeological Viking ship finds were grave goods from high-ranking people and, like other grave goods, were intended to help the deceased on their journey to the afterlife.

The ship

Shipbuilding went through a great development even before the Viking Age. The main types can be distinguished: the longship and the cargo ship, known as Knorr. Longship and Knorr were equipped with sails and had one deck. The space between the frames was called rúm and was the place to stay for the crew: on deck for rowing, below deck for storage and sleeping. Some ships also had cabins. Women generally stayed below deck in danger and rain. There was no toilet, you sat on the railing. The klogang on the ship was called ganga til borðs.

The ships were different, although their sizes followed certain rules. Therefore, they could be identified from afar. The Egils saga says: “Kveldulf and his son Skallagrim always kept a good eye out on their trip along the coast in summer. No man saw as sharply as Skallagrim. He saw Hallvard and Sigtrygg on their sailing trip and recognized their ship, having seen it before früherorgils sailed on it. “The king's ships were particularly impressive. They were used for representation and were used in combat. The scene before the Battle of Svolder is famous:

“So the rulers all went up onto the spar with a large retinue, and they saw a multitude of ships sailing out to sea together. And now they discovered a particularly large and shiny ship underneath. Then both kings said, 'There's a particularly shiny ship over there. That may be Ormurin langi . ' Jarl Erich replied to this and said: 'No, Ormurin langi is not that.' And it was as he said, for it was the ship Eindridis von Gjemse. Shortly afterwards they saw a ship sailing towards it, which was even bigger than the first. Then King Svend said: 'Now Olav Tryggvason is frightened. He doesn't dare to sail on his ship with the head of a kite. ' Then Jarl Erich replied: 'That is not the king's ship either. I know this ship and the sail. Because the sail is colorfully striped. This belongs to Erling Skjalgsson. Just let it sail. Because better for us is a gap and a hole in King Olav's fleet than this well-equipped ship is there. ' After a while they saw and recognized the ships of Jarl Sigvaldi, which were heading towards them for the spar. Further on they saw three ships sailing in, and one was particularly large. Then King Svend called out that his men should go to the ships, because 'there' he meant 'the Ormurin is coming.' Then Jarl Erich said: 'You have many other large and magnificent ships besides the Ormurin langi. Let's be patient. ' Now some men said: 'Jarl Erich does not want to fight and does not want to avenge his father. It will be a great shame for us, and it will be told in all countries, when we lie here with such a warlike force while King Olav is sailing the high seas here in front of all of us. ' After they had talked for a while, they saw four ships sail up. But one of them was a huge dragon ship and completely gilded. "

Ormurin langi was the largest ship that had ever been built in Norway, but not the largest dragon ship per se. It is doubtful whether the ship was actually completely gilded. The description is probably due to the increase in tension in the story, but gilding is attested. The poet Þorbjörn Hornklofi says in his poem about the battle of Hafrsfjord: “ From the east came quills / battle whispers / with yawning heads / and golden sculptures ” and the poet Guþorm Sindri calls them in a poem “gold jewelry horses” and names the ships of the Danish opponent "dragon". But one could clearly tell them apart. In any case, some of them were painted. The skald Sigvat, an eyewitness to the battle of Nesjar, says in a poem that Jarl Sveinn had the heads cut off on the "black bow" in order to free himself from the grappling hooks of the king's ship. The ships of Knut the Great , on which the fleet leaders sailed, were painted above the waterline, his own ship also had a gilded dragon's head, and the dragon's head on the ship of his comrade Håkon Jarl was also gilded.

Judging by all types of sources, literary, archaeological and pictorial material, the scorpionfish on the ships were relatively rare. According to the Landnámabók, it was forbidden to sail into the home port with the kite head on the stem. The country's guardian spirits could be raised or driven out. So the dragon head had an aggressive content. On patrols, he was supposed to drive out the enemy's guardian spirits. Whoever drove away the guardian spirits of the attacked country and subjugated the country was the new local ruler. Therefore, in the sources, the ships with dragon heads are regularly attributed to the leaders of the companies.

The mast was a special place. There the skipper informed the crew of his decisions.

Since the sails were sewn together from woven webs, they could be equipped with different colors, which was apparently also a distinguishing feature. That speaks against the idea that all sails were striped red and white. The dragon ship Hákon Jarls had a blue, red and green striped sail. The sail of Harek's ship "was white like freshly fallen snow and streaked red and blue".

Ship types and characteristics

All Scandinavian ship types had in common that they were never designed exclusively for sailing. This meant that the ships designed to carry loads had a large crew on board in relation to the cargo.

The naming of the boats after the number of rowers has its origins in the time when ships were exclusively rowed. The earliest evidence of northern European sailing ships are images on Gotland picture stones from the 7th century. The classification took shape around the year 1000. In the 13th century, the classification in skipslæst , i.e. according to the load-bearing capacity.

Boats

The boats were named after the number of oars . The pairs of oars were rowed by one man each. Boats rowed by a single man had no name of their own. They were all called bátr . However, in old Swedish laws the term þvæaraþer bater occurs for two- rowers .

- In two places a boat with two pairs of oars used to catch seals is called Ferærðr bátr .

- A boat with three pairs of oars was called sexæringr . This boat was mostly rowed, but apparently could also use sails, according to a source. If you equate the sexært in the inventory list of Skarð from 1259 with the selabatur in the inventory list from 1327, such a boat was also used for seal fishing .

- A boat with four pairs of oars was called áttæringr or skip áttært .

- A boat with five pairs of oars was called teinsæringr or skip teinært . But not all five were always used. But often the crew was also bigger. In the Grettis saga Kap. 9 six men are mentioned on a teinsæringr . The sixth man is likely to have taken the helm. Elsewhere in the saga, even 12 men are mentioned. In other sagas there are 15 and 20 men, in the Laxdœla saga Kap. 68 even reported 25 men on such a boat. During the Sturlung period, these boats were also used in sea combat in Iceland.

- In some sagas a tolfæringr (with 6 pairs of straps ) is mentioned. According to the non-historic Króka Refs saga , 60 men are said to have traveled from Denmark to Norway on such a boat.

- Every larger ship carried at least one, but mostly two boats. One was being towed, one was behind the mast across the deck or above the cargo. How the ship was brought out of the water onto deck or lowered is not known. The merchant ships, which were less suitable for rowing, were also towed a certain distance by means of a rowboat.

- There were also small ferries to cross rivers and straits. The smallest were called eikjur , which means “flat-bottomed boat”. According to Landslov VII 45, a rope to which a raft or an eikja was attached should be stretched over small rivers, over which a country road ran . No ferryman was required here. But there were also ferries ( farskip ) with a ferryman, especially in straits and larger rivers, on which people, cattle and cargo were transported for a fee. In Iceland the vehicle was called ferja . These ferjur were bigger than the eikjur .

Small ships

Ships larger than the tolfæringr but smaller than the longships were not designated by the number of oars or rowing benches, but by the number of rowers on one side of the ship. Incidentally, the names were not always clear. This is probably due to the fact that the pairs of oars were not handled by one man and there were also no special oar seats, but rather the rowers sat on the deck beam by removing a deck board for each rowers. Incidentally, there were two basic types:

- The ship type karfi sometimes overlaps in the springs with both the largest boats and the smallest longships with 13 rowers on each side. One time a tolfæringr is called “ karfi ”, another time a fifteen oarsman . These ships mostly also carried sails. They were probably lighter and of lower carrying capacity than the longships of the same size.

- There was also the skúta . The word corresponds to the word " Schute ". It also overlaps with the boats and longships. Sometimes an eight oarsman ( áttæringr ), sometimes also a fifteen oarsman ( fimtánsessa ) is referred to as " skúta ". As a rule, however, a distinction is made between skútur and langskip . The skútur are named after the row seats on one side. They mostly carried sails. The léttiskútur and the hleypiskútur , which were used as package boats , scout ships ( njósnarskútur ) or as messenger ships , were also sailed . They were easy and quick. They were therefore often escort ships for fleets. In the naval battle of Svold , Jarl Eirik placed his smáskútur in a semicircle around King Olav Tryggvason's fleet to prevent the enemy from escaping by swimming. They also served as transport ships for the fleet. Like the karfar , they were also drawn across the country. Private ships were mostly skútur with a crew of 30. As a rule, they were furnished and unadorned for practical use only.

These small ships had the great advantage that they could be transported overland. They therefore played a major role in the civil war, where some fighting was fought on the Norwegian inland waters.

Longship

Longships ( langskip ) were warships ( herskip ). They were named after the number of row seats ( sessa ) or the spaces ( rúm ) on one side. The smallest guy was the thirteen-seater. The twenty- seater was initially the most common passion ship and therefore the most widespread. The ship was also called "Skeide". One ship with 30 row seats on one side was an „ ritugsessa , one with 25 seats was halfþritugt skip (a ship that was very popular because of its maneuverability), and one of 35 seats was half-made skip. The fact that the thirty-seater had 60 and the thirty-five-seater 70 belts results from the information about Ormurin skammi (thirty-seater) and King Harald Hardråde's great dragon ship (thirty-five-seater). Larger ships were rare. Håkon Jarl is assigned a forty-seater, the Anglo-Scandinavian King Knut the Great a sixty-seater, but this is considered a legend. Duke Skúli (1239) had a thirty-six seat and Bishop Håkon Erlingsson had a forty-five seat. In contrast, the famous Ormurin langi only had 34 seats. However, the number of seats is not a reliable indicator of the size of the ship. King Sverre's “Mariussúð” had 32 seats and was the largest ship in the country. In 1206 three long ships with two rows of oars are said to have been built. The Gokstad ship had 16, the Oseberg and Ladby ships had 15 row benches. Haithabu wreck 1 had 24-26 row banks.

These large ships, the battleships of that time, had a higher side wall and a taller fort, so that the enemy ships could be fought from above, but they were not easy to board. However, this had a disadvantage: They became heavier, lay deeper in the water and were therefore more cumbersome to maneuver. In the battle of Fimreite , the Maríusúð did not succeed in turning her bow away from the land where she was still fortified and against the enemy. The Kristsúð was a pure combat ship, the largest and also the last to be built on this scale of 30 seats and more. It has been shown that with the enlargement the disadvantage of the increasing clumsiness had obviously already exceeded the usefulness of a capital ship with this size.

In the comparison of Kvitsøy 1209 between the civil warring parties Bagler and Birkebeiner , it was agreed that no larger ships than fifteen-seater could be used in a sea battle. Skúli circumvented this rule by building ships with 15 oar seats that were as big as twenty-seaters.

The terms Dreki and Snekka (also referred to as "Snekkja" or "Snekke") differentiate the longships according to the type of their stem jewelry: Dreki had a dragon head, Snekka a snail-shaped spiral. Bardi was possibly the name of a ship with an elongated and reinforced stem.

The longships were limited in their seaworthiness. To put it bluntly, it was fair-weather ships. Numerous replicas but the seaworthiness of Viking ships was proved, such as 1893, when you have a race between a replica of the Gokstad ship, the "Viking" and a replica of the Santa Maria , discovered by Columbus America, the World's Fair in Chicago transverse across the Atlantic. It was described that the Viking glided as easily as a seagull over the crests of the waves and, with an average of 9.3 knots, was significantly faster than the Columbus ship with 6.3 knots. The clinker construction of the hull encouraged the formation of air bubbles during the journey, on which the ship could then glide faster through the water like on an air cushion.

In the fjord of Roskilde Vikings had sunk a longship 30 meters long and 3.80 meters wide with space for 70 warriors so that enemy boats could get caught in the shallow water when entering the fjord. In 1962, about 900 years after it was sunk, archaeologists set about digging it up again and rebuilding it. With a strong wind and a flared sail and a sail size of 120 square meters, it could go up to 20 knots.

Merchant ships

Merchant ships ( kaupskip ) had a slightly different design, as they were not designed for speed but for carrying capacity. However, they were not only used for trade trips, but also during war. They were wider, more high-sided and were not classified according to rowers, but according to their carrying capacity. This was expressed in læst , with one læst corresponding to about 2 tons. They were less geared towards rowing and more towards sailing. They only had oar holes fore and aft, but not amidships. There was free space there for the cargo. For most of them, the mast was fixed and could not be folded down.

As with warships, there were different types and sizes. Smaller ships were “karven” and “skuten”. Karven were rarely larger than 13-15 rúm (usable space between the frames) and were used for both trade and war. In 1315 the Hålogaländer received permission to fulfill their obligation to suffer with this type of ship. The bigger guys were Knorr , Busse and Byrding.

The largest Knorr (Haithabu 3) found so far, already measured but not yet recovered, had a load-bearing capacity of around 30 and a water displacement of around 40 tons at a length of 22 m.

The Busse ( Búza ) was originally a warship. But in the post-Viking era in the 13th and 14th centuries, this term exclusively referred to merchant ships. This results from the English customs lists for Norwegian merchant ships from 1300 onwards. This ship name soon spread across the entire North Sea. Busse and Knorr were roughly the same size, but still must have been different types, because the words are never used interchangeably for the same vehicle. The difference is assumed to be in a different bow shape. At the end of the 13th century, the buses had practically ousted the Knorr as an overseas ship.

The Byrding was originally a trading ship designed for coastal travel. She was also used as a supply ship for the fleet, but she also occurs on the routes to England, the Faroe Islands and Iceland. The only known thing about this guy is that he was short, broad and shorter than Knorr and Busse. The crew was 12-20 men. Reports that Byrdinge became longships by lengthening the keel and converting them suggest that there could not have been any major differences between these two types.

In contrast to these ships, which were always driven by both sails and oars, the post-Viking Age cogs ( Kuggi ), which called at Norway from the 12th century, were exclusively sailed like the Frisian ships. Around 1300 the cog was the predominant type of ship in all of Scandinavia.

Ship names

Particularly representative ships were also given a name. That was the name of the first large warship, Olav Tryggvasons Kranich . Then he brought a ship with him from Helgeland called Wurm . Then he had an even bigger ship built with 34 oar seats on each side. That was the long worm . The predecessor ship was called The Short Worm since then . The ship of Olav the Holy was called Karlhöfði (man's head) because it carried a carved king's head instead of a dragon's head. He also had a ship called the Vísundur (bison) because it carried a bison head on the stem. This is also said to have been gilded. Another ship has come down to us under the name Tranann (crane). King Håkon Håkonsson named his ship Krosssúðina . Ships were also named after whoever gave it. That was the name of the Knorr Sveinsnautr donated by King Sveinn . Or it was named after the one from whom it had been stolen, like the ship Halfdanarnautr . Later ship names were derived from the current owner: Reimarssúð (1370) and Álfsbúza (1392). Christian names were also often used during the Christian era: Postolasúð , Krosssúð , Ólafssúð , Katrínarsúð , Sunnifasuð etc. It was not until the 15th century that ships contain saints ' names without additions, e.g. B. Pétr sanctus .

| Well-known longships with at least 30 seats | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Surname | Time of construction | Client | Number of seats |

| Tranann | Nidaros 995 | Olav Tryggvason | 30th |

| Ormurin skamma | Salten before 999 | Big farmer Raud | 30th |

| Ormurin langi | Nidaros 999-1000 | Olav Tryggvason | 34 |

| Rogaland before 1020 | Erling Skjalgsson | 30th | |

| Visundur | Nidaros 1026 | Olav Haraldsson | 30th |

| "Búzu-skip" | Nidaros 1061-1062 | Harald Hardråde | 35 |

| Maríusúð I | Nidaros 1082-1083 | King Sverre | 32 |

| Ógnabrandur | Nidaros 1199 | King Sverre | 30th |

| Nidaros 1206-1207 | King Inge | 36 | |

| Nidaros 1206-1207 | Håkon Jarl | 32 | |

| Nidaros 1206-1207 | Peter Støyper | 32 | |

| Ólavssúð | unknown | Birkebeiner | 31 |

| Langfredag | Nidaros 1232-1233 | Skuli Jarl | 36 |

| Kross-súð | Orust 1252-1253 | Håkon Håkonsson | 35? |

| Maríusúð II | Bergen 1256-1257 | Håkon Håkonsson | 30th |

| Kristsúð | Bergen 1262-1263 | Håkon Håkonsson | 37 |

The team

The crew was called “skipssögn”, “skipshöfn”, “sveit”, “skipverjar”, or “skiparar” in norrøn. This suggests that there was no maritime profession that could have trained a terminus technicus .

The Gulathingslov gives information about the crew in §§ 299 ff. Then there was a skipper (“stýrimaður”, “skipstjórnamaðr”, “skipdróttinn”, “skipherra”) (on the warship, if possible, unmarried and without own household). He was usually appointed by the king on warships and had unlimited authority. There was also a ship's cook (matsveinn, matgerðarmaðr) and the rowing crew (“hásetar”, on warships also “hömlumenn”) selected by the skipper. Since there was no fireplace on board, the ship's cook only came into action when going ashore. After bylov of Magnus Håkonsson he should be brought three times a day on land: once to fetch water, the other two times to cook. The hásetar had to take turns to operate the sails and the rudder, to drain the ship and to keep watch. The stafnbúar provided the lookout for the fairway and the enemy sjónarvörðr . There were also other special watch duties: for the archipelago the bergvörðr and the rávörðr for the sails. On land there was the bryggjusporð for the landing stage and the strengvörðr for the anchor rope . Lot decided on the night watch. There are also cases handed down where the crew was called together at the mast in a dangerous situation to vote on how to proceed.

In the case of merchant ships, the command of the master was not unlimited. This has to do with the fact that merchant ships often belonged to several people as part owners . Then there were the owners of the cargo and passengers. In this way, the other parties involved could object to the departure if they considered the ship unseaworthy or overloaded. The course of the ship could also be discussed. Several helmsmen were only allowed on board for the trip to Iceland. The team strength here was 12 to 20 men.

The heavy labor was evenly distributed among the crew. If five or more seats were vacant on a twenty oarsman (with 40 row benches), it was not possible to run out. The lower limit of a warship was a ship with 13 oar banks. The longships had a bulwark at the front, on which the best fighters stood. Because you fought Steven against Steven in the water.

How many men there were on a ship is not stated. For a leiðangrskip (which had to be provided by the population as part of the general conscription) it was prescribed that each rowing bench had to be occupied by two men. This also results from the order in Gulathingslov that there is a shortage of food on a ship if there is no more provisions than a month of flour and butter for two departments (" tvennom sveitum "). The farmer Harek received a boat from King Olav Tryggvason, “on which 10 or 12 men could row. … The king also gave Harek 30 men, capable and well-armed fellows. ” On a boat with six row benches, 30 men with equipment could be transported next to Harek. It is reported about the "Long Worm" that the royal standard-bearer on the stem and two men with him, a little more than twelve men on the foremost deck and 30 men in the vestibule in front of the main deck. Then there is the rowing team. That was 68 men for one shift. When relieved, 136 men are to be expected. “ Jarl Erling had a ship with 32 row benches and a corresponding space. On this he drove on Víking or when he called the army. 240 men or more were then on board. “Usually a man would row an oar. But in special cases more men could be used per strap. In the battle of King Sverre against the Baglers at Strindsjøen in 1199, it is said that the king had four men put on each oar when he pursued Bagler.

The men slept in the rúm between the frames below deck. An average of three to four men can be expected in one rúm . Isolated information about eight men (for Ormurin langi) are doubtful. That was only possible on short expeditions in good weather.

On one ship there was also a ship's court (“mót”), which was called by the “reiðumenn” at sea on the mast, on land on the landing stage.

Equipment

Marine equipment

The Frostathingslov specifies the ropes: ropes for hoisting and striking the ra, two bream , two supporting ropes, main ropes, two bulkhead ropes, lifting ropes and over six reefing straps. Particular emphasis is placed on the sail. It was sewn together from several webs. The mast also had an "ás", the ropes were made from seal skin. In addition, scooping vessels (a ladle " austr " for low ships , a bucket " austrbytta " for high- sided ships ) had to be brought. This also included a channel ( dælea ) across the ship into which the bilge water was poured and through which it then ran outboard. Small boats had a small hole in the hull with a peg ( farnagli ) from which the water could drain when the boat was pulled up on the bank. The king's mirror from the 13th century should also reflect the long-established rules of proper ship equipment when it warns:

“Take on board two to three hundred yards of Vadmel (cloth), which may be used to mend the sail if necessary, lots of needles and enough thread or ribbon; even if it seems irrelevant to mention something like that, there is often a need for it. You must always have a lot of nails on board with you, as big as are suitable for the ship you have, both spike and rivet nails. Good plumb lines, carpenter's axes, gouges and drills and all other tools that are necessary for ship work. "

The list is obviously incomplete as, for example, the hammer is not mentioned. This apparently also included an anvil. Because in the battle between Jarl Håkons and the Jomswikings a man threw him against his opponent on a ship. Before that, a fighter had repaired the crossguard of his sword on him. Several grappling hooks were also carried on warships. Their use is mentioned in the sea battle at Svolder.

The mast

The Viking ship had a mast that consisted of a fir or pine trunk that was tarred, as can be read from the poetic expression "kolsvartir viðir" ("coal-black mast"). Fastening the mast was a particular challenge when the hull of a ship twisted elastically in rough seas. The stages of development to mature technology are not handed down, only the finished solution for the Viking ships. Various sources indicate that the mast of a 20-rower was 60 feet and that of a 30-rower was 80 feet. Usually it was amidships or just before the center. He was standing upright or inclined slightly backwards. The latter gave him greater stability in the aft wind. For this reason, the backstay was missing on some ships . On smaller ships, the mast went through a hole in a transverse band and stood in a recess in the keel. In large vessels of the foot stand in a the keel mounted massive bar, the keelson ( "kerling") (cross-link Gogstad ship 40 cm thick and 60 cm wide and about 4 frames). In their case, the transverse band through which the mast passed was reinforced by a beam, because at the height of the mast and the short distance between the keel and the deck, the leverage was great. The beam is the heaviest single piece of the entire hull: 5 m long, 1 m wide and 42 cm thick in the middle, but bevelled towards the ends, made of the best oak. The mast was then fixed with a solid wooden wedge. The mast could be removed. In addition, the hole in the keel pig had a rounded track to the front, which enabled the mast to be folded down without lifting up to the first support. Therefore the mast could be folded down very often and very quickly. The mast was not lowered in battle. There was often a masthead on top of the mast. A flag was waving on the top. In an upright position, it was held by shrouds and a stage made of hemp or seal leather . It consisted of the bowstay and the main ropes, one or more on the port and starboard side. In addition, there were one or two auxiliary ropes on the windward side (“stöðingar”) for upwind sailing. The mast ropes were mostly made of walrus skin, a sought-after import product from Greenland. Ottar also gives the length that was fixed in the tribute of the Finns: 60 elna = approx. 36 m.

sail

The sail was a so-called square sail and had the shape of a rectangle. There were different types of production.

material

The most important fiber materials for weaving sails from the Viking Age were wool , flax and hemp .

According to him, in Caesar's time the Venetians had sails made of leather. The Primary Chronicle mentioned in connection with a campaign Olegs to Constantinople Opel in 907 and subsequent agreements that "as the most valuable canvas pavoloken " was used. However, one does not know what it was and suspects fine linen. Oleg's ship is also attributed to silk sails. These could have been made of linen with silk sewn onto it. Silk was known to the Vikings since the 10th century. Purely silk sails have only become known worldwide from novels (e.g. in: Gene Del Vecchio: The Blockbuster Toy !: How to Invent the Next Big Thing. Pelican Publishing, 2003.). They would probably not have been stable enough for more northern areas either. They were prestigious grand sails. The sails of King Sigurður jorsalafari are said to have been made from “ pell ”, which is often translated as “velvet”. The velvet has its origin in Persia and was not used in Europe until the 13th century. Pell probably means "decorated fine fabrics". They were sewn onto stable substrates. In Skuldelev the sail was made of wool a particularly long-haired breed of sheep, which was highly water resistant, leading to a boiled wool was processed, the wadmal was called and cash and measure of value was.

Around 1 million square meters of sail area were required to equip the Viking fleet. The sails of a merchant ship of the Knorr class made of wool weighed about 200 kg and the weaving took about 10 years of work. The sails of a warship with a crew of 65 to 70 men had to use over 1.5 tons of wool, the weaving required 60 to 70 years of work.

construction

According to the images on old seals, the sails often consisted of strips of fabric sewn together. The looms of the time allowed the production of long lengths of wool. But sails composed of smaller pieces of fabric are also shown. The net structures shown on the leeward side are likely to have been ropes that absorb the wind pressure on the sail and thus increase the tear resistance. The net structures shown on the windward side are interpreted as sewn-on reinforcements with additional strips of fabric or leather. Royal ships had canvas sails. The ships depicted on the coins of Haithabu are also said to have essentially had canvas sails. A rope was sewn into the hem of the sail for reinforcement. The representation of the sails on the Bayeux Tapestry is interpreted differently. Some say they were tied into a point at the bottom to reduce the sail area. Others believe that the triangular shape is due to a somewhat clumsy perspective representation. In the early illustrations on coins, seals, embroidery and paintings, sails are shown with different structures. In addition to vertical stripes, there are also squares. But it does not tell whether they are sewn together from square pieces of fabric, or whether they are reinforcing strips sewn on. There were also crossing diagonal stripes ("með vendi"), as can be seen on Gotland picture stones and old coins. It looks like there have been sails where the fabric panels were braided diagonally. But this resulted in two layers of fabric lying on top of each other, which is rather unlikely due to the high material consumption, at least it was used very rarely. Later a line of gording was pulled down vertically in the middle of the sail . Different types of ships also had different types of sails, as can be seen from the different names.

The sails were often treated with a mixture of ocher, grease and tar, which is an effective impregnation.

The sail was held by the mast and the yard and spread with an áss , especially when sailing on the winch. It is said of such an áss that it protruded so far over the ship's side that it could knock a man overboard on a ship sailing past. That means that the sails were very wide below. When no sails were set, the yard and probably the áss lay on stands amidships. The yard consisted of a round piece of fir wood that was thickest in the middle. The case with which the yard was hoisted went through the masthead. After hoisting, the other end was often attached to the rudder as a backstay. The sail could be adjusted with the ropes at the lower corners of the sail. A passage in the Sigurðar saga jórsalafara shows that the Norwegians knew how to sail so close to the wind that the yard was almost parallel to the keel.

The sails were often colored, but not only red and white, as in the representations of modern times. From the pre-Viking era, Flavius Vegetius describes Renatus in Book Four, Chap. 37 of his Epitoma rei militaris that the sails of the reconnaissance boats had been colored blue for camouflage. When Canute the Great set out from England to drive Olav the Saint from Denmark, his fleet is described:

“Knútur hinn ríki hafði búið her sinn úr landi. Hafði hann óf liðs and skip furðulega stór. Hann sjálfur hafði dreka þann er svo var mikill að sextugur var að rúmatali. Voru þar á Höfuð gullbúin. Hákon jarl hafdi annan dreka. Var sá fertugur að rúmatali. Voru þar og gyllt Höfuð á en seglin bæði voru stöfuð öll með blá og rauðu og grænu. Öll voru skipin steind fyrir ofan sæ. Allur búnaður skipanna var hinn glæsilegsti. Mörg önnur skip Höfðu þeir stór og búin vel. "

“Knut the Mighty had an army together to be able to leave the country. He had an extraordinarily large force and wonderfully large ships. He himself had a kite ship. It was so big it counted sixty row benches, and on it were gold-plated dragon heads. Jarl Håkon also had a dragon ship. This numbered 40 row benches. This too wore gilded dragon heads. But the sails were striped blue, red, and green. These ships were painted all over the waterline, and all their equipment was the most magnificent. They had many other ships, big and wonderfully equipped. "

Possibly there were also monochrome sails, because the skald Sigvat, who saw the fleet, writes in his price poem:

|

Og báru í byr |

Blue sails - the blowing |

There is even mention of purple sails, and kite ships sometimes wore embroidered sails. If the scraps of fabric found in the Oseberg ship are part of a sail, then the sail was red. According to Sturla, gold wire was even used for embroidery. It was probably only the sails of the leaders, which were made of linen. Because the wool sails were pigmented and therefore gray to brown. Pigmentless wool was rare and of high quality, but it was a prerequisite for dyeing.

There were various methods of changing the sail area. The sail could be made smaller by tying it with ribbons. These reefing tapes can often be seen on pictures. There was also the method of tying transverse strips of fabric at the bottom, so-called bonnets , for enlargement .

Winches were used to hoist the sails. There were both windlass and capstan used.

Later a foresail was apparently attached to a bowsprit. In any case, such a bowsprit is mentioned in a document from 1308.

The anchor

Originally, a heavy stone with a hole to pull the anchor rope through was used as an anchor in boats. However, the Scandinavians adopted the iron anchor of the Romans very early on, as can be seen from the adoption of the foreign Latin word ancora in the language: Old Norse “akkeri”, Irish “accaire”, old Swedish “akkæri”, “ankare”, Anglo-Saxon (already in Beowulf ) "ancor". This anchor consisted of a shaft with two anchor claws and a wooden anchor stick inserted at right angles to these. On the Gokstad ship this was made of oak and 2.75 m long. The top of the anchor had an eye that held a ring through which the anchor rope or chain was pulled. At the lower end there was a fixed eye to which a rope with a buoy was attached, which marked the position of the anchor on the water surface. This rope also served to rescue the anchor in the event of the anchor rope breaking. It also loosened the anchor from the bottom if the ship could not be pulled over the anchor's position by the anchor rope. The anchor was in the bow of the ship. In later times, a capstan was also used to pull the anchor up. Often several anchors had to be used because the anchors were not particularly heavy. If there was no place to swim , a second anchor was deployed in the opposite direction.

belt

Rowing the boats were with belts fitted. These were usually planed and tarred. On the Gokstad ship, oars made of pine wood were found that were 5.30 to 5.85 m long (shorter in the middle of the ship, longer at the ends). During rowing, the oar in smaller boats was attached to bars that were attached to a reinforcement on the top corridor, the gunwale, or to real vertical oarlocks with an oar loop as an abutment. The oar loop that was attached to the oarlock and through which the oar was put was made of walrus skin or willow whip. On larger ships, the straps were put through oar holes in one of the top rows of planks, which was specially reinforced. The oar holes were approximately 12 cm in diameter and had a slot to allow the wider rudder blade to pass through. When rowing, a third of the oar was inboard. On the Gokstad ship, the oar holes amidships were 48 cm above the waterline. There were strap flaps on the inside with which the strap holes could be closed. Where the deck beams were not used as the oar seats, there was an oar bench for each oar pair. On the longships, each rower probably had his own rowing bench, so that there was a passage in the middle. There is no archaeological evidence for this. Usually a man carried a thong. However, since the row benches were occupied several times, two, rarely even three, men could carry an oar with heavy rowing. In old Norwegian the ships were named after the rowing benches on one side, in old Swedish after all seats, so that an old Norwegian 20-rower was a 40-rower in old Swedish. The cargo ships of the saga era only had row benches fore and aft.

Catering

According to § 300 of the Gulathingslov, the rower's equipment consisted of flour and butter for two months for each sling and a tent and a sling . However, it is mentioned that they have to provide the bonds. But if food was scarce on the way home, you could go ashore and slaughter two of a farmer's cattle for a fee. From this one can conclude that meat was also part of the supply. Dried halibut strips ( riklingr ) and stockfish ( skreið ) also belonged to bread. There were storage communities that were mötunautar . For the trip to Iceland, three beer kegs with water were required for two men. But they also took drykkr with them, which used to be beer without a specific name, but it may be whey. In addition, boiling kettles ( búðarketill ) were on board.

overnight stay

On the coastal voyage, there was no sailing at night, but a berth on land was sought. At night, when one was at anchor, the mast was turned down and the ship's deck was covered with a tent. These tents have not been proven archaeologically. The tents were apparently across the ship's deck, because the tent opening was facing the ship's wall. There were two tents, one on the front ( stafntjald ) and one on the rear deck ( lyptingartjald ), which was assigned to the king on the king's ship. The tents consisted of several individual pieces that were knotted together while camping. They overlapped like the planks of the ship. At the ends of the tents stood two gable boards that rose from below within the railing, crossed each other at the top, and through which a long horizontal pole was stuck, over which the tent ceiling was thrown. This ridge pole rested on tent supports. Lights could also be lit in the tent. They even had tables.

There were tents for the country too. Such country tents were found on both the Gokstad ship and the Oseberg ship. They had a footprint of 5.30 x 4.15 m. The interior height was 3.50 m and the other 2.70 m. At the ends of the tent there were two precious carved windboards that crossed at the top. The carvings with their dragon motifs suggest magical defensive spells against ghosts that could haunt the tent at night. In any case, this suggests the resemblance to the dragon heads at the ends of the ship, whose magical meaning has been handed down. Because according to the Landnáma you had to take it off when you went to the country so as not to turn the spirits of the country against you.

One slept in double sleeping bags (húðfat). The two who slept in it were roommates ( húðfatfélagar ), a particularly close relationship. Beds have been found in the ships at Gokstad and Oseberg, but they are probably not part of the normal equipment. A bed was a marvel of carving on the bedpost. Below deck, between a frame on each side, was a box that two men used to store their equipment. The clothes at sea usually consisted of sewn together skins ( skinnklæði .), Which were taken off while rowing.

The ships also had dinghies, a small one stowed behind the mast and a larger one in tow. You could sleep under the smaller one.

The combat equipment consisted of the sword and the shield of the bow with at least two dozen arrows and a spear. In reality, however, many more were carried along. Because spears are thrown in the battle descriptions for a very long time, and it is said of King Olav Tryggvason in the sea battle of Svolder that he always threw spears with both hands during the fight. To the contemporary reader it must have made sense that enough spears were in stock on a ship to fight a lengthy battle.

Ship damage

About the quality of the hull, the Gulathingslov says:

“Now the king sends his men to the county to check the ship's equipment and men, and they or the skipper describe the ship as not clear to sea. But the other side describes it as clear to sea. Men from a different ship position should be appointed to swear whether the ship is clear to sea or not. But if they don't want to swear, let them put their ship on the water and check their craft. They should leave it for five nights to poetry and then use it up. If a man can keep the ship dry by scooping out onto the coastal driveway, the ship is clear to sea. "

The mast, the Ra (h), the oars, the rudder, the ropes and the sails were particularly at risk at sea and were often damaged and had to be repaired along the way. The above equipment was also on board. But collisions could also occur when entering the port or in narrow waters. The Bylov gives certain damage tariffs for sailing .

When a storm threatened, side frames ("vígi") were placed on the lower merchant ships. They were placed loosely and were similar to the raised borders ("víggyr dill") used as parapets on warships. The planks could loosen due to violent rolling. In contrast, a rope was pulled through under the keel as a transverse strap ("þergyrðingar") and tied to the deck with bars. In addition, damaged ropes were replaced with new ones.

The nautical

Coastal shipping

Shipping in the Viking Age was essentially coastal shipping, including long-distance traffic. When traveling on the Norwegian coast, a distinction was made between the þjóðleið hit ytra , útleið or hafleið located outside the archipelago and the within the archipelago þjóðleið hit innra or innleið fairway . On more distant seas (Friesland, Mediterranean), the native coastal shipping routes were adopted. As a rule, you sailed during the day and went to a sheltered bay in the evening.

Nautical marks

Landmarks and sea marks have always been important for coastal shipping. These were characteristic landscape formations, islands, mountains and estuaries. Bronze Age burial mounds also served as landmarks. In addition, many navigation marks were artificially set up, waiting areas, crosses, towers, special trees. In 1432 the Venetian merchant Pietro Querini traveled south from Lofoten and reported that the whole time had been steered after waiting.

Sailing instructions

Sailing instructions played a relatively minor role in coastal shipping. An early description of the coast can be found in Ottar and Wulfstan in his report to King Alfred the Great on the journey into the White Sea. However, the report is very imprecise, both for the distances that are given as the duration of the sail without specifying the speed of the ship, and for the directions that are only very roughly described as the cardinal points.

Pilotage

Since nobody could know the entire sailing area , pilots (norrøn: leiðsögumaðr , old Swedish: lédhsagari ) who knew the location of the treacherous rocks under water were hired for trips outside the closer home area . The helmsman was responsible for ordering the pilot. There were so many pilots in Bergen that they formed a guild.

Depth measurement

Strangely enough, the plumb bob for measuring the water depth is nowhere mentioned. There is also no Old Norse word for it. This is all the more striking since the Anglo-Saxons knew the plumb bob and the dipstick and archaeological finds prove their existence for the Scandinavian region as well. It was only Olaus Magnus (16th century) who took the use of the plumb bob as a matter of course in his work Historia de gentibus septentrionalibus . The forkr , a rod for pushing the ship from land or from other ships, may have served as a bearing stick .

Landing

The Naust (also Nausttuft) is a characteristic building type of Norway. In Naust, ships from the Iron Age and the Viking Age were stored and serviced, especially in winter. Traces of these boathouses can be found numerous on the coasts, where the banks are shallow enough to pull the relatively light ships ashore. In those days this was the usual form of landing. In northern Germany, the first Hude locations were built in the pre-Viking era .

Ocean shipping

Shipping routes across the North Sea

For a better understanding of the traditional sailing instructions, see also geodetic visibility

Red: Traditional sailing instructions from Hernar to Iceland

Green: Past Iceland to Greenland

Pale blue: Drift ice zone

Various routes were used on the North Sea voyages. This was especially true for trips to Iceland and Greenland . The Landnámabók's sailing instructions state that a ship coming from Norway should stay 100 to 120 km south of Iceland en route to Greenland. At this distance, the 2119 m high Öräfajökul on the southern edge of Vatnajökull near the coast could still be seen. In the version of the Hauksbók, the trip to Greenland is described as follows:

"Af Hernum af Nóregi Skal sigla jafnan í vestr til Hvarfs á Grænlandi, ok er þá siglt fyrir norðan Hjaltland, svá at því at one sé þat, at allgóð sésjóvar sýn, en fyrí sunnan he á sðumó, svá hlá hl svá fyrir sunnan Ísland, at þeir hafa af fugl og hval. "

“From Hernar of Norway you should sail right west to Hvarf on Greenland, sailing so far north of the Shetlands that they can only be seen when visibility is very good, and so far south of the Faroe Islands that the The lake extends to the middle of the mountains and so far south of Iceland that you can see birds and whales from there. "

"Hernar" is identified with the island Hennøy (now part of the municipality of Bremanger ), 170 km north of Bergen in a branch of the Nordfjord . Hvarf is the southern tip of Greenland (Cape Farvel). If you wanted to stay as far north of the Shetlands as indicated in the sailing instructions, you had to follow a WSW course. The course passed at an assumed eye level of the helmsman of four meters above sea level about 70 km north of the Shetlands and 70 km south of the Faroe Islands . The information about Iceland suggests a distance of about 100 km. Strangely enough, the Hauksbók does not mention that Iceland is in sight at this distance. At the level of the Faroe Islands, the course had to be changed to the NW.

The island route to Iceland also went via the Shetlands and the Faroe Islands. It was much longer than the direct route from Stad in Norway to Hornafjörður in South Iceland, but on this route you had to drive 700 km continuously with no land view. The island route usually began at the aforementioned Hernar. To the east of Hernar are 800 m high mountains. This means that on the stretch from Hernar to Unst in the Shetlands, the native mountains could be seen for 80 km. Unst can be seen from 70 km away. Half of the distance, about 15 hours, had to be sailed with no land view. It was 300 km from Unst to Suðuroy in the Faroe Islands, of which 140 km had to be sailed without land visibility when visibility was good, and less than half the distance between the Faroe Islands and Iceland. However, this only applies to extremely good visibility, which cannot be assumed as a rule. In addition, the sailing instructions said that the islands should not be approached, but circumnavigated at a great distance.

This route is rarely mentioned in sources and is not always the same. After the Landnáma, Flóki Vilgerðarson drove from Flókavarði near Ryvarden , where Hordaland and Rogaland meet, on his journey to Iceland first to the Shetlands. Auðr en djúpauðga ("the clever one") first drove to the Hebrides , from there to Caithness , then on to the Orkneys and finally across the Faroe Islands to Iceland. But that wasn't a continuous trip to Iceland. Rather, the route was due to various visits and stops en route. In general, the trips to Iceland in the Landnámabók over the islands are never due to navigational reasons, but either visits there, or the people decide to go to Iceland only on the islands.

Of the 300 to 400 landowners of the Landnámabók, one can say with some certainty that 250 trips originated in Norway. Departure locations are named for 70 trips. They stretch from Vík (Oslofjord) in the south to the Lofoten in the north. The departure points in Sogn , Hordaland and Agder are the most common. Uniquely determined can be Flókavarði , Dalsfjörðr (a fjord in Sunnfjord in Vestland fylke.), MOSTR ( Mosterøy ) Strind (Strinda, a district of Trondheim ), Veradalr and Viggja (in the community Skaun ). Hernar is not mentioned yet. Also Yrjar (now Ørland ), an important port of departure from the sagas, is not clearly explained in the Landnáma as a base of Iceland ride. Despite the abundance of trips to Iceland described in the Landnámabók, it does not answer the question of the preferred Iceland route. Nothing can be derived from the sagas either. Because they only describe intermediate points of the journey if they have a function in the described event. Otherwise the journey will end with the phrase: “ ... there is nothing more to tell about your journey before you came to XY. “Passed over.

The helmsman had it easier on the reverse trip from Iceland to Norway. Because he didn't need to “look for” Norway. The risk of sailing past the long coast to the north or south was low. Nonetheless, the problems here are also considerable: the names of the destination ports cannot always be identified, which is also due to tradition. Even a well-known place like Lofoten is sometimes called Lófót , sometimes Lafun , sometimes Ofoten with edge correction in Lofoten. The destinations of the Icelanders were largely determined by the respective trade prospects. So Snorri writes:

“Þat var á au sumri, at hafskip kom af Íslandi er áttu íslenzkir menn; þat var hlaðit af vararfeldum, ok héldu þeir skipinu til Harðangrs, því at þeir spurðu, at þar var fjölmenni mest fyrir. "

“It happened one summer that a seagoing ship came from Iceland belonging to Icelanders. The ship was loaded with coats to be sold, and the Icelanders steered their ship to Hardanger because they had learned that most of the people would be there. "

For another part, political reasons were decisive: they wanted to visit the king and join court society. The royal court mostly resided in Trondheim. Or you wanted to avoid the royal court in cases of conflict and headed for southern destinations. A third criterion was family relationships. Icelanders often first visited their clan that had remained in Norway. Most of the trips ended at Trondheim and north of it.

The seafarers in the Viking Age are often ascribed special skills in navigation. This does not agree with the sources. There are very often random wanderings that show that one considered oneself lucky when one actually reached the intended goal. The fact that this nevertheless happened relatively often has less to do with the art of navigation and more to do with the fact that one only drove across the North Sea when persistently good weather was to be expected so that one could keep the direction. They were absolutely helpless in the fog. It was not possible to determine the position afterwards. When King Håkon Håkonsson sailed to Scotland with a large fleet in 1263, the ships lost sight of each other. Some ships came to the Shetlands, others to the Orkneys.

Cardinal points

The four corners of heaven were Norðri, Suðri, Austri, Vestri . The field of view was divided by the four main axes ("Höfuðætt"). In between, four more axes are placed so that eight ættir are created. When naming them, the north-south axis was assumed and the directions were named after their relationship to the mainland. So northeast was landnorðr , southeast landsuðr , northwest útnorðr and southwest útsuðr . This designation was retained everywhere, including Iceland. The winds were also named after them: landnyrðingr, landnorðingr, útsynningr and úrnorðingr.

There was still no magnetic compass , and so one had to determine the position and direction according to the position of the sun, moon and stars ( astronomical navigation ). The compass was already described by Alexander Neckam in the 12th century and was probably known on the mainland, but the word leiðarstein was not used until the beginning of the 14th century ( Landnámabók in the version of the Hauksbók , written around 1307). There the compass is mentioned in the story of Flóki, but at the same time it is said that it was not available at the time of the conquest. From when it was used cannot be determined. The word is based on the word leiðarstjarn ("way star"). The term leiðarstjarn for the pole star also appeared relatively late. Since the leiðarstein was certainly not present at the time of the conquest around 870, and is assumed to be known shortly after 1300, it must have been introduced sometime in between. The written sources do not allow a more precise statement. The extra-Nordic reports on the compass from 1187 onwards, however, suggest that the point in time near 1300 appears likely.

In 1948 a semicircular wooden disc (fragment) from around 1200 with a diameter of seven centimeters was found in Greenland, which has notches on its outer edge and part of a hole in the middle. CV Sølver interpreted this fragment of wood as a bearing disc ( solar compass ). and a number of publications have followed him in. There was a shadow pen in the middle and the north direction could be determined from the azimuth of the sun and the shadow of the pen. This is countered by the fact that the notches on the edge are carved irregularly, although precise carving has long been mastered, i.e. one quadrant has eight, the other nine notches, so that more than the 32 notches assumed would have been found on the full circle. In addition, the disk is much too small for this purpose. In addition, amplitude tables and calendars would have been required. You cannot assign any function to this board, and so there are no limits to your imagination. The arguments against the interpretation as a target disc are likely to predominate.

Furthermore, from time to time there is written from a sun shade board ( sólskuggafjöl ), a board with a needle. The length of the shadow of the needle allowed a conclusion about the latitude. This information comes from Niels Christopher Winthers book Færøernes Oldtidshistorie (Faroese Ancient History). Winther does not give a source, but apparently got this information from the handwritten notes of the Faroese pastor Johan Henrik Schrøter (1771–1851). This in turn has evaluated older manuscripts, but these have not survived. Its historical reliability is doubted in specialist circles.

In 1267 a rather unusual description of how the northern latitude was estimated is given.

“… Then on the day of Jacob’s Mass they drove a long day rowing route south towards Króksfjarðarheiði; there it was freezing at night at the time. However, the sun shone day and night, and when it was in the south, it was no higher than that of a man who lay across from the ship's side in a six-oar, the shadow of the ship's side, which was facing the sun, threw in the face. "

The result is that this ship had no better way of determining the position of the sun on board. Another aid to determine the position of the sun in cloudy weather is said to have been the legendary sólarsteinn ( sun stone ). He is mentioned in various sources. The best known is that King Olav the Saint checked the position of the sun by his host Sigurðr with the help of such a sólarsteinn when the snow was blowing and the sky was overcast . There have been many attempts to attribute a real mineral to this story. But even cordierite , which Thorkild Ramskou claims to have identified as sólsteinn , does not have the properties described in the sources. Rather, as with the Twilight Compass, a clear zenith is required, while the low sun can be covered. There is also not a single source that proves that such a sólsteinn was carried on board. In the Grænlendinga saga, on the other hand, Bjarni reports:

“But they did head out to sea when they were ready to sail and sailed for three days until the land was under the horizon. But then the wind stopped, and north winds and fog came up. And they didn't know where they were going, and that took many half days. Then they saw the sun and could determine the cardinal points "

Bjarni came from the richest families in the country and would certainly have brought a sólsteinn with him if such a navigation aid had existed.

The sólarsteinn also appears in some inventory lists of monasteries, without it being possible to find out anything about its nature or function. Now the inventories show the sólsteinn for barely a century, and it is not certain that they mean the same stone mentioned in the Olavs saga. Schnall offers a stone magic interpretation, especially since the saga about Olav the Saint is strongly influenced by salvation-historical concerns. He thinks it may have been a ruby and considers the saga passage to be a learned allegorical representation of the author.

Numerous archaeological finds show a ship or weather vane named in the sources veðrviti . It is mentioned several times in the sources. The oldest specimens are trapezoidal with two right angles. The long side was up, the short side was down. Later (from around 1000) the outside was made round. A few bronze specimens have survived, most of them lavishly decorated and gilded. Opinions are divided about the function. Some interpret them as ship pennants, others as stander. Some written sources indicate that they were attached to the mast. In the saga of Olav the Saint it is said: “He had the sails and mast lowered, the veðrviti removed and the whole ship above the waterline covered with gray fabric.” Since this passage describes how Harek disguises his warship as a merchant ship , this leaves the end to it admitted that such veðrviti were not common there. But from the various references it can also be inferred that the Veðrviti were not installed in the same place on all ships. They probably had some on the mast, the others on the stem.

In summer you could only watch the sun, as the nights were too bright in the far north. When the sky was covered, you could use the angle to the sea as a guide for some time. If the sky stayed overcast, you had to sail at random. This situation of not knowing where you were at sea was called havilla (= floating around in the sea without direction). Sailed within sight of land for as long as possible ( visual and terrestrial navigation ). The distances were given in very general terms, e.g. B. that the mountains were halfway below the horizon. The measure of distance was otherwise "vika sjáfar" (nautical mile) "Rimbegla", a learned old Icelandic computist treatise from the 12th century, says that the "tylft" (= 12 vikur sjávar ) defines a degree of latitude. A vikur sjávar is a nautical mile of eight to ten kilometers, so that one tylft corresponds to about 100 to 120 km. In other sources the circumnavigation of Iceland is given as 12 tyftir , which corresponds to 210 geographic miles and is very close to reality. The unit of time at sea was the dægr , which was then also used as the sailing distance . What a " dægr " is is controversial. The majority, however, assume a time span of 12 hours. The "Rimbegla" teaches that two degrees of latitude make a dægr sigling . This results in an average speed of two and a half geographic miles per hour, which would correspond to about 10 knots. It should be noted, however, that no longships were used on these routes, but cargo ships that were not built for high speed. Since the sources for longer distances by sea often give the routes in dægr , the average speed of the cargo ships of the time can be calculated from this. The calculations roughly confirm this speed under optimal conditions. The calculation of the distance was purely an estimate on the high seas. Before the invention of the log , the distance traveled could only be roughly determined. Things didn’t get better with time. The day was divided into eyktir , which corresponded to the fourth part of the day - a very variable amount in view of the strongly varying day lengths. The helmsman now had to estimate his position at sea from the course and distance. Attempts were also made to determine the height of the sun. A message about a voyage to Baffin Bay made in 1267 contains the following determination of the height of the sun: “ When the sun was in the south, it was no higher than the shadow of the ship's side facing the sun hit a man lying across the ship on the deck in the face . “This way of determining the height of the sun seems to have been common, as the top plank of the ship was called“ sólborð ”(sun board).

The sailing instructions were an important help . The sails descriptions in Adam of Bremen in his Gesta Hammaburgensis Ecclesiae Pontificum IV, one must be disregarded because it is nachwikingerzeitliche additives. On the other hand, his rough travel description about the journey from Frisians past the Orkneys to Iceland in IV, 40 of his work up to there is quite believably contemporary.

The sailing instructions at that time were only slightly related to astronomical navigation, namely in the information on the cardinal direction. Rather, terrestrial points of contact are predominant: island silhouettes, places on the sea with certain animal populations, birds that come from the land, etc. No length measures are given, but time measures, as the distances covered could not be measured. One of the most interesting sailing instructions is contained in the Landnámabók and should be given here as an example:

“Svo segja vitrir menn, að úr Noregi frá Staði sé sjö dægra sigling í vestur til Horns á Íslandi austanverðu, en frá Snæfellsnesi, þar he skemmst, he fjögurra dægra haf í vestur til Grænlands. En svo he says, ef siglt he úr Björgyn rétt í vestur til Hvarfsins á Grænlandi, að þá mun siglt vera tylft fyrir sunnan Ísland. Frá Reykjanesi á sunnanverðu Íslandi er fimm dægra haf til Jölduhlaups á Írlandi (í suður; en frá Langanesi á norðanverðu Íslandi er) fjögurra dægra haf norður til Svalbarsbota í h "

Smart men say that from Cape Stad in Norway to Cape Horn in East Iceland it is seven “ dægr sigling ” westwards and from Snæfellsnes to Greenland, where the distance is shortest, four “ dægr ” high seas to the west. And so it is reported that if you want to sail right-west from Bergen to Hvarf on Greenland, you have to sail a “ tylft ” south of Iceland. From Reykjanes in South Iceland to Jölduhlaup in Ireland it is five “ dægr ” high seas to the south .; but from Langanes in northern Iceland to Svalbard in the large bay it is four " dægr " high seas to the north. "

The location of “Jölduhlaup” has not been identified, but “Svalbard” means Spitzbergen . The “big bay” could be the bay on the west coast of the island of Spitsbergen.

The sailing instructions are based on optimal visibility and wind conditions.

Other factors

Shipping was highly dependent on the wind direction. Only the wind falling from behind, which was called "byrr", could be regarded as a favorable airflow. Cruising on the winch was not possible because the keel required for this was missing. There wasn't even a word for it. If the wind direction was unfavorable, you had to jibe , causing the ship to go backwards in a circle and lose its way. To sail on the wind was called “beita”, which is derived from bíta (bite). The Norwegians knew how to sail close to the wind quite early on, while Ottar could only sail upwind and had to wait for the wind direction to change when changing course. Replicas of Skuldelev3, however, have sailing properties that allow sailing up to 60 ° upwind.

So not all ships could sail on the winch. The ancients would rather wait days, even weeks for a favorable wind and clear sky, than sail out into the unknown. In the Königsspiegel it is therefore advised not to go on long voyages after the beginning of October and not before April. In Iceland, merchant ships were not allowed to sail after September 8th (Jónsmessa). Sometimes the sail had to be recovered completely and the mast lowered. This was also practiced when there was no wind, where the ship did not obey the helm, or when there was a headwind. The ship was then allowed to drift (“leggja í rétt”). There was a risk that the ship would face the waves broadside. This had to be countered either by rowing or by setting the sail again, so that at least the stern was turned towards the wind. There were no sea anchors or equivalent devices to keep a ship perpendicular to the waves.

The current also played a not insignificant role. It moved the ship in the direction of flow depending on the speed. Ocean currents are mentioned several times in the sources. The saga of Olav the Saint says: “ Two summers later, Eyvindr úrarhorn left Ireland from the west and wanted to go to Norway. But because the wind was too stormy and the current impassable, Eyvindr turned to Osmondwall (Isle of Hoy) and was stuck there for some time because of the weather. “And in the saga of Olav Tryggvason it says: “ Then Óláfr sailed from the west to the islands and lay down in a harbor because the Pentlandsfirth could not be sailed. ”

The birds could tell that there was land beyond the horizon. There were sailing instructions for the voyage from Norway to Greenland that one should sail so far south of Iceland that one could see birds from the land (“hafa fugl of landi”). Birds were also on board for this purpose. Flóki let ravens soar on the journey from the Shetlands to Iceland to determine in which direction the land lay. This method is very old and is already mentioned by Pliny . There were also natural features on land, but also artificial landmarks (“viti”). On the Orkneys , fires were lit when a ship approached ("slá eldi í vita"). But beacons and trees that were placed on shallows were also in use. This method was also in use early on. In the Edda song " Helgakviða Hjörvarðssonar " it says:

|

Dagr er nú, Hrímgerðr, |

The day is shining, Hrimgerd:

Atli |

It was also important to know the ocean currents and tides ("fløðar"), as you did not sail against the current.

Of course, all of the described aids and observations were not sufficient for safe navigation.

"En er þeir skildust Ólafur konungur og Þórarinn þá mælti Þórarinn:" Núber svo til konungur sem Eigi er örvænt og often can verða að vér komum eigi fram Grænlandsfer konungurðinni, ber oss að eg ðíslandi Skalenna s að yður megi líka? ""

“But when they said goodbye, King Ólav and Þórarinn, Þórarinn asked: Now it is so, Mr. King, as it is not unlikely and often can happen that we cannot make the Greenland voyage, that it will take us to Iceland or other countries fails - in what way should I deal with this king that it seems good to you? "

Elsewhere, the aim of a skipper is particularly emphasized. From Þórarinn rammi it is said:

"Hann hafði lengi verið í förum og svo farsæll að hann kaus sér jafnan Höfn þar er hann vildi."

"He had been at sea for a long time and he was so happy that he always found the port he wanted."

However, it cannot be concluded from this that every trip between Iceland and Norway would have been an incalculable risk. By far the largest number of journeys went without any significant incidents.

The first reaction to storms was to reduce the size of the sail. This was done by lifting the lower part of the sail with ropes from the ship's deck. For this purpose, holes were made in the sail at the reinforced edges through which a rope was pulled up alternately from front to back and back to front and then deflected towards the deck. When the rope was pulled, the sail was folded up from below. But if the wind was too strong for that, in that the pressure of the wind on the masthead became too strong, the yard was lowered instead and the sail reefed below. By linking the reefing straps, of which a passion ship should have at least six, the sail could be reduced to a minimum of one reef. When you could no longer sail with a single reef , the sail was salvaged. Since a swaying mast puts a lot of strain on the mast shoe and can damage the keel, the mast was turned down. If you couldn't do that anymore, then you cut him off. The draft was reduced by throwing cargo overboard.

Reconstruction on Gotland

In spite of their significant appearance, the Bildsteine sailing ships were not large. The crew shown and the length of the boat were related. A comparison with Dalarna's church boats shows that the number of crew members gives the length of the ship in meters between the stems . This means that the ships shown had lengths between seven and 12 m. The need for large ships was smaller on the Baltic Sea than on the North Sea. The ships from Oseberg and Gokstad went on an Atlantic voyage and were of an appropriate size. This also applies to some of the Danish ships from Skuldelev. There were different requirements on the Baltic Sea and the boats were built accordingly. The journeys led across rivers, lakes and narrow waters, which also included taking the boats overland. Relatively small ships that had to be just big enough to cross the Baltic Sea came into question for this. In order to serve the Gotlanders' trade, they should have the following properties: Easy to tow or pull, sail and row quickly, as well as sufficiently resilient and large enough for a crew to protect the loaded goods.

The sails and rigging of the picture stones, as well as the remains of a boat that was probably dated to the 11th century and was found in the Bulverket of Tingstäde , were the starting point for the reconstruction of a Gotland merchant ship. The boat from Tingstäde is similar to boat finds from Danzig -Ohra in Poland and Ralswiek on Rügen . Secondarily used planks of a similar ship have been found in the older culture layer of Lund . The reconstruction was built in Visby in 1979 . It bears the Gutnish name " Krampmacken ", is built in clinker construction, is eight meters long, has nine frames and has space for ten rowers.

The majority of the sails have constant proportions between the height and width of the sails. The height corresponds to half the width (also the length of the yard ). The mast and yard are the same as the length of the ship within the stern. After three years of testing with "Krampmacken", the background to these dimensions was known. For effective rowing, the mast must be folded down and stowed together with the yard and sail inside the railing. Since the benches closest to the stems are higher than the others, the mast must be able to lie below them, which corresponds to the proportions shown on the stones.

When sails first appeared on the stones cut around AD 600, they show two versions. One is "horizontally checkered". However, this type of sail was apparently not the general or long-term one. The image of a sail on the likely dating back to the 7th century stone Tollby in Fole was because of the sharpness of detail (also in the presentation of the pods network and the luff ) to a starting point for the reconstruction of the sail. The stone by Tollby has a diagonal checkered weave, which presumably does not represent colors, but sewn-on leather strips that promote durability.

No prehistoric sails have yet been found in the north. The materials used for the sail were wool, hemp and linen. The material could be confirmed in another context. The wool of some primitive sheep species is so water repellent that a woolen fabric remains relatively light even when wet. On Gotland there are remains of an old tribe of sheep that have received exactly these characteristics.

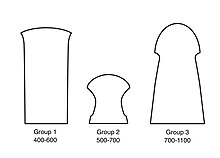

Dewlap

The elegant boats with the high butted but fragile stems could not have been particularly seaworthy. This was improved on ships that were not so representative by placing triangular boards, known as dewlaps, under the stern. This happened at the time when the "dwarf stones" appeared among the Gotland picture stones, all of which show dormer ships. The Wammensteven had the advantage that ships of this type were very stable on course, and you could sail high upwind with only little drift. Not only merchants but also warships were equipped with stems like those shown in the Broa II picture stone from the 8th or 9th century on Gotland or the stones from Hunnige and Tullatorp.

Finds from Viking ships

- Norway

- Kvalsund boat - 7th century

- Gokstad ship - 9th century

- Oseberg ship - built around 820

- Mykleust ship - 9th century

- Tune ship - built around 890

- Cargo ship from Klåstadt near Larvik - sunk around 990; Remnants in the Tønsberg Maritime Museum

- Denmark

- Ladby ship - added around 925 in ship grave

- Skuldelev Ship Cemetery - 11th century

- Roskilde 6 - after 1025

- Finland

- Russia

- In 1997 a wreck was found in Dalnaya Bay near Vyborg .

- Estonia

- Germany

- Haithabu 1 - built around 985

- Haithabu 3 - (measured but not yet recovered: a 22 m long and 5.5 m wide cargo ship built around 1030, which was even larger than the Knorr Skuldelev 1 ).

Haithabu 2 and 4 are Prahme , i.e. barges of the continental European type. In a chamber grave near Haithabu, the remains of a ship from around 900 that is similar to the Skuldelev 5 find were also found .

Individual evidence

- ↑ Vita Anskarii, chap. 7th

- ↑ Egils saga, chap. 27.

- ↑ Þorbjörn Hornklofi in Heimskringla, Harald's saga hárfagra. Cape. 18th

- ↑ Heimskringla. Magnúss saga góða. Cape. 7th

- ↑ Heimskringla. Ólaf's saga helga. Cape. 123: “ A barge was just approaching you. And the ship was easily recognizable: the front part of it was painted on both sides and coated with white and red paint, and it also carried a striped sail. "

- ↑ Heimskringla. Ólaf's saga helga. Cape. 50.

- ↑ a b Heimskringla. Ólaf's saga helga. Cape. 147.

- ↑ Else Mundal: Midgardsormen and andre heidne vesen i kristen context. In: Nordica Bergensia 14 (1997) pp. 20-38, 31.

- ↑ Landnámabók, chap. 164.

- ↑ Heimskringla. Ólaf's saga helga. Cape. 158.

- ↑ a b Brøgger, p. 287.

- ↑ Ole Crumlin-Pedersen; Tomorrow Schou Jørgensen, Torsten Edgren "Ships and traffic" in "Vikings, Waräger Normans. The Scandinavians and Europe 800 - 1200", exhibition catalog 1992, ISBN 87-7303-559-9

- ↑ Björn Landström "Since skibene Forte sejl", sesame, Copenhagen 1978, ISBN 87-7324-428-7

- ^ Brøgger, p. 207.

- ^ Brøgger, p. 208.

- ↑ Falk, p. 90.

- ↑ Also sexærr bátr, skip sexært. Old Danish siæxæring, Norwegian seksæring or seksring.

- ↑ Falk, p. 90. Today the word sexæringr in the Faroe Islands denotes a vehicle rowed by 12 men, i.e. with 6 oars on each side. (Falk, p. 90, footnote 1).

- ↑ Diplomatarium Islandicum, Vol. I, p. 597.

- ↑ Diplomatarium Islandicum, Vol. II, p. 635.

- ↑ Falk, p. 91.

- ↑ Falk, p. 91; Johan Fritzner: Ordbog over Det gamle norske Sprog. Oslo 1954. III, p. 711.

- ↑ Jónsbók, landsleigubálkr 45th

- ↑ To the previous Falk, p. 92.

- ↑ Falk, p. 95.

- ↑ Falk (p. 95) quoted: með margar skútur og eitt langskip. (With many skútur and a longship) and more examples.

- ↑ Falk, p. 95 with sources.

- ↑ Brøgger, p. 210.

- ↑ In Sweden, the total number of row seats seems to have been the determining factor. The old Swedish fiæþærtiugh sæssa (forty seater ) corresponded to the old Norse tuttusessa (twenty seater ). Falk, p. 97.

- ^ Brøgger, p. 208

- ↑ Falk, p. 97 with quotations from the sources.

- ^ Brøgger, p. 213.

- ↑ Falk, p. 97 with further examples.

- ↑ Falk, p. 97 f.

- ^ Brøgger, p. 273.

- ↑ Brøgger, p. 209

- ↑ Falk, p. 12.

- ^ Rudolf Pörtner: The Viking Saga . Düsseldorf / Vienna 1971, Toplak / Staeker 2019.

- ↑ http://www.geo.de/GEOlino/kreativ/wiedergeburt-eines-wikingerschiffs-3003.html?eid=78706 Rebirth of a Viking ship, GEOlino.de

- ↑ a b Brøgger, p. 285.

- ↑ Simek 2014, p. 42.

- ↑ a b Brøgger, p. 286.

- ↑ Heimskringla. Ólaf's saga Tryggvasonar. Cape. 72.

- ↑ Heimskringla. Ólaf's saga helga. Cape. 144.

- ↑ Falk, p. 32.

- ↑ " ... en að lyktum tóku menn Magnúss konungs hann með skipsögn sína ... " () Magnúss saga berfætts (The story of Magnus Barefoot). Cape. 9.

- ↑ var Eindriði drepinn og öll hans skipshöfn (Eindriði was killed and his entire crew) Flateyarbók I, 448.

- ↑ "Þá gekk sjálfur Magnús konungur með sína sveit upp á skipið" Magnúss saga góða. (The story of Magnus the Good) Chap. 30th

- ↑ "Vóru þá skipverjar engir sjálfbjarga nema Skald-Helgi" (There was none of the team who could save themselves except Skald-Helgi) Skáld-Helga saga. Cape. 7th

- ^ Gulathingslov § 299; Frostathingslov VII, 7.

- ↑ a b c Falk, p. 5.

- ↑ bylov IX, 16.

- ↑ Buckle, p. 10.

- ↑ Buckle, p. 11.

- ↑ Frostathingslov VII, 13; Landslov III, 10; Bylov III, 11.

- ↑ Heimskringla. Ólaf's saga Tryggvasonar. Cape. 75.

- ↑ Heimskringla . Ólaf's saga helga. Cape. 22nd

- ↑ King Sverre Sigurdsson, chap. 54.

- ↑ a b Brøgger, p. 274.

- ↑ Falk, p. 97 f.

- ↑ Frostathingslov VII, 5. An otherwise unknown word that Meißner translates as " Stenge (for spreading the sail)".

- ↑ Falk, p. 6.

- ↑ Probably wrong translation. "Sókn" are search hooks to get objects out of the water on board.

- ↑ Heimskringla. Ólaf's saga Tryggvasonar. Cape. 41.

- ↑ This and the following statements are taken from Falk, pp. 55 ff.

- ↑ a b Lise Bender Jørgensen: The introduction of sails to Scandinavia: Raw materials, labor and land. In: Ragnhild Berge, Marek E. Jasinski, Kalle Sognnes (eds.): N-TAG TEN. Proceedings of the 10th Nordic TAG conference at Siklestad, Norway 2009, Archaeopress, Oxford 2012, pp. 173-181.

- ↑ De bello gallico III. 13, 6.

- ↑ Möller – Wiering, p. 64 f.