Reefing

Reefing describes the process of reducing the area of the sails on a sailing ship , mostly during or in anticipation of bad weather with strong winds.

Reefing is necessary because with increasing wind more pressure acts on the sails, so that the ship would normally heel more (lean). This would put unnecessary stress on the ship (including the sails and masts ). Severely heeling ships are also less maneuverable (see weathering ). In addition, severe heeling reduces the speed of a ship (among other things, because the sails are ultimately so inclined that they are no longer optimally in the wind); since the ship would be slowed down a bit by the incline anyway, the reduction in sail area by reefing only leads to a limited reduction in speed. Very strong heeling due to wind pressure can lead to a so-called sun shot , i.e. the loss of the rudder effect, and in the case of dinghies, catamarans or high seas even capsizing a ship.

The reefing has to be foresighted - i. H. if possible before a strong increase in the wind - this activity can be dangerous in a storm with heavy seas and strong winds, depending on the rigging (type of sails, masts, etc.) . Instead of reefing, a sail can be recovered entirely and replaced by a smaller one. In the case of the headsail, for example, this can be a storm jib (small headsail made of very resistant material), with the mainsail a so-called try sail (small sail, also made of resistant material).

Taking the reef out of a sail is called 'reaching out' or 'pouring out a reef'.

Different types of reefing

Bindereff

The Bindereff is particularly suitable for mainsails and mizzen sails. Here, the corresponding sail to the halyard hauled down a particular piece and the luff , the leading edge of the sail, with an eyelet, which is also referred to as Reffauge or reef point on the tree mounted. The “new” lower leech of the sail can be pulled tight at the leech, the rear edge of the sail, with a line, the Smeerreep .

So that the reefed sailcloth does not flap back and forth on the tree, it is loosely tied to the tree with several lines, the reefing straps, which are fastened in a series of eyes ("reefing gates"). As an alternative to reefing straps, a lazy bag can also be used, which holds the canvas like a bag.

A sail usually has several reefing rows so that the sail area can be adapted to the respective wind strength. In this case one speaks of the first, second, third etc. reef. The first reef is the one that reduces the sail area the least and is set first when the wind increases.

Schlappreff

This simplified form of the Bindereff is the preliminary stage for the following variants. Here only the thimbles on the sail neck and on the (new) nock are tied to the main boom with lines. The rest of the sail hangs loosely from the tree.

Two-line meeting

In a further development step, the two thimbles are not connected directly to the boom, but are redirected to the mast or even into the cockpit via tackles. In the latter case, the sail area can be reduced simply by loosening the main halyard and hollowing the two reefing lines. Nobody has to leave the cockpit to operate the lines or hang the reef thimbles in the hooks on the boom, which is an important safety aspect with increasing winds.

Single line reef

The single-line reef is a special form of the two-line reef. Here, a single line is looped from the cockpit over the front reefing, then deflected aft through the boom and tied to the clew. Because this design involves considerable friction losses, it is only suitable for small boats. On larger boats, a mechanical slide is used in the boom to bring the two lines together. However, this has the disadvantage that it increases the weight and size of the tree and that it contains mechanics that are difficult to maintain in the event of problems.

Furling

With furling systems , part of the sail is furled as required. A headsail is usually wrapped around the forestay , a mainsail or mizzen sail in the tree or - now very common - in the mast.

The disadvantage of furling and thus of furling systems as a whole is that in the event of technical problems with jammed sails, the sails cannot be moved forward or backward, which can be dangerous when the wind increases. With conventional reefing systems, the main halyard can be thrown in an emergency to completely recover the sail, which no longer works with furling systems.

Drehreff

An almost infinitely variable reefing facility, similar to the furling systems, is made possible by a rotating reef that can be used in smaller sailing boats. The excess cloth of the mainsail is wrapped around the tree, which can be rotated lengthways (axially); after reefing, the tree is then secured against further twisting. In the simplest case, this security is achieved with a special Lümmel fitting , the connection between the tree and the mast. If the tree is turned with a hand crank via a gear or worm gear, one speaks of a patent meeting.

People's meeting

At the Volksreff, a hand crank is inserted directly into the rotating boom through holes on the front of the mast. The height of the position of the hand crank on the mast can be adjusted with gear constructions and it can also be moved to the rear side of the mast.

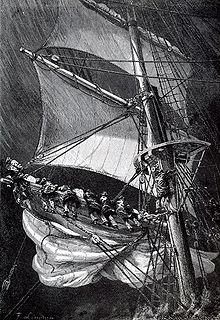

Square sail

With square sails , the canvas is reduced to a yard by being pulled up . To do this, the operating team, also known as top guests , has to go up to the rigging of the ship. As an alternative, reefing by means of gordings can be mentioned here . The sail is drawn up through pockets worked into the canvas and ropes running through them, similar to a curtain . In general, however, this reefing method is classified as not as effective and unsuitable for very strong winds. For this reason, only a few square sails of a ship are equipped with it, mostly only the upper topsail .

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ Segler-Lexikon, Schlappref, das

- ↑ Segler-Lexikon, single line reefing system, das

- ↑ Segler-Lexikon, single line reefing system, das

- ↑ Segler-Lexikon, furling system, the ; Furling mainsail

swell

- Joachim Schuldt; Sailors lexicon ; Delius Klasing; 13th edition 2008; ISBN 978-3-7688-1041-8