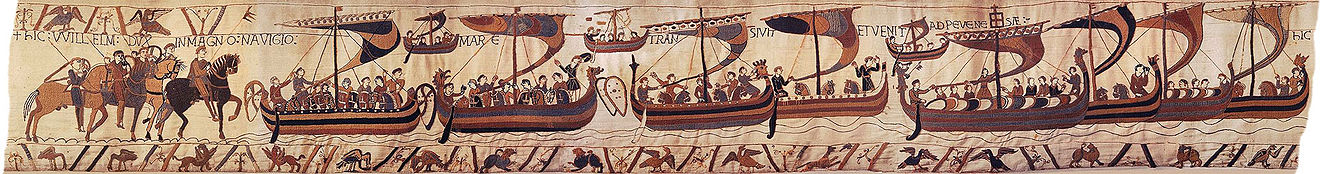

Bayeux Tapestry

|

| Bayeux Tapestry, detail |

|---|

| around 1070 |

| Textile art; Embroidery on linen |

| 48 to 53 × 6838 cm |

| Center Guillaume le Conquérant, Bayeux |

The Bayeux Tapestry [ baˈjø ], sometimes also called the tapestry of Queen Mathilda , is an embroidery on a 52 centimeter high strip of cloth that was created in the second half of the 11th century . The conquest of England by the Norman Duke William the Conqueror , depicted in pictures and text over 68 meters in 58 individual scenes, begins with a meeting of Harald Godwinson, Earl of Wessex , with the English King Edward and ends with the Battle of Hastings on October 14, 1066. The final scenes are missing, so the original length of the cloth is unknown.

Because of its abundance of detailed individual representations, the well thought-out iconography and the quality of the craftsmanship, the Bayeux Tapestry is considered one of the most remarkable pictorial monuments of the High Middle Ages . The details reveal many aspects of medieval life. There are details of ships, shipbuilding and marine life, costume and jewelry, the fighting style and equipment of Norman and Anglo-Saxon warriors, the royal hunt, relics , rule and representation as well as coins and money. It also shows the first known pictorial representation of Comet Halley , which reached the point closest to the Sun around the time of the events depicted. The picture belongs to the Romanesque style phase. It has clear Anglo-Saxon and Scandinavian features and is at the beginning of the so-called Anglo-Norman period.

The Bayeux Tapestry has been exhibited in the specially built Center Guillaume le Conquérant in Bayeux in Normandy (France) since 1982 . A copy from the second half of the 19th century, largely faithful to the original, can be found in the City Museum of Reading . Since 2007, the carpet of the UNESCO program "Memory of the World" (part of the World Soundtrack Awards ).

execution

The Bayeux Tapestry is between 48 and 53 centimeters wide over its length of 68.38 meters. While the opening scenes are intact, the ending is torn off. Originally the so-called carpet measured over 70 meters and showed Wilhelm's coronation in the final scene. With wool and linen are for this work of textile art everyday materials have been used. This is believed to be the reason why the Bayeux Tapestry lasted for nine centuries. A work decorated with gold thread, gold flakes and precious stones would probably have been cut up by looters over time. Overall, the carpet is in good condition, even if it has wax stains, cracks and similar damage. Traces of repairs and reconstructions are clearly visible in numerous places.

On the surviving scenes, a total of 623 people, 202 horses, 55 dogs, 505 other animals, 27 buildings, 41 ships and boats and 49 trees are depicted in the main frieze and the border borders. The main frieze is accompanied by a descriptive Latin text that emphasizes fifteen individual people and eight locations by naming them or explaining the plot. For example, the text of scenes 27 and 28 reads: HIC EADWARDUS REX IN LECTO ALLOQVIT FIDELES (“Here King Edward is in bed talking to his family”) and ET HIC DEFUNCTUS EST (“And here he died”). Occasionally the text is insufficiently spaced, and words are sometimes split or abbreviated. It is therefore assumed that the text was only inserted into the design after the figures, the details of the background and the border borders had already been designed. Due to the way the threads are routed, however, we know that the embroidery of the main frieze, border and text was carried out at the same time.

Embroidery base

The work is not actually a carpet, as this term is associated with knotted or knitted work . Rather, it is an embroidery work carried out on nine interconnected lengths of linen . The individual lengths of linen are very carefully sewn together so that the seams are hardly noticeable. It was only in the 19th century that it was recognized that the carpet was made up of several strips joined together, and until 1983 it was assumed that eight strips were made. Only during the examination and cleaning in the winter of 1982/83 was another seam discovered. The two longest lengths of canvas measure almost fourteen meters, an unusual length for woven fabrics at the time. The other tracks are between six and eight meters long, the last two tracks are only about three meters long. The fabric has 18 or 19 warp and weft threads per centimeter and is therefore relatively fine. The original weaving width was about one meter and was divided lengthways into strips of about 50 centimeters before embroidery. This corresponds roughly to the width on which a sticker can still work well. At the seam between the first and second lengths of linen, the embroidered upper edge is shifted by a few millimeters. At least at this point, the linen strips were only joined after the embroidery was completed.

Yarn and embroidery

At least 45 kilograms of wool were used for the embroidery. Since a more detailed examination and cleaning in the winter of 1982/83 we know that the work was originally carried out with two-ply woolen yarn in ten different colors and not, as previously assumed, eight. The main colors are terracotta red, blue-green, light green, yellow-brown and gray-blue. Other colors have been used in later repairs and reconstructions, including a lighter yellow and several shades of green.

There is little difference between the colors of the front and back of the carpet. The fact that the front is only slightly faded suggests that the yarns have been dyed carefully. The synthetically dyed yarns that were used for repairs in the second half of the 19th century are now partly more faded than the original yarns. The yarns had been dyed in the wool before the fibers were spun . Only three different vegetable dyes were used. The dyers achieved the yellow and beige tones with dye-trimmings . The green tones were obtained from a mixture of dyer's ressead and woad . Pure woad gave the blue colors, and madder dyed the wool red.

The use of the colors sometimes looks random. Horses are also embroidered in red or blue. A three-dimensional effect of the otherwise imprecise scenes was achieved by using different colors for the outer and inner side of pairs of legs. The representation of flesh tones was dispensed with; Faces, hands or naked bodies are only represented by outlines.

Originally three different types of stitches were used: Surfaces are predominantly executed in the so-called Bayeux stitch , while the stem stitch was used for the outlines and inscriptions. In some places there are also split stitches. Chain stitches can only be seen on the areas of the carpet that have been repaired over the years.

Design and implementation

There are no contemporary sources describing how the Bayeux Tapestry was made. However, there are references to the type of execution and sources describing the production of comparable works.

It is believed that the design of the main frieze was made by an artist who had direct knowledge of the battle. This is supported by the uniformity of the presentation, the detailed reproduction of military weapons and the realistic battle scenes. Several people were probably involved in drafting the accompanying text. This is indicated by the different spelling of names. For example, the spellings Willem , Willelm or Wilgelm are used for the name Wilhelm . The carpet was probably initially designed on a smaller scale. The design was then presented to the client and, with his approval, drawn in the scale that corresponded to the embroidery work. In order to save material costs, it was common to specify the colors to be used on the stickers only by means of abbreviations. There are no traces of a preliminary drawing or auxiliary lines on the linen strips. However, such preliminary drawings using charcoal and ink were common. For embroidery, the linen strips were lashed to wooden frames, which in turn rested on trestles. The stickers usually worked so that one hand was above and the other below the line of linen.

Workshops that were commissioned with such embroidery work usually made liturgical robes or sumptuous altar covers, which were donated to churches or monasteries by their clients. Typical works also included representative robes such as the coronation gown , one of the imperial regalia , which was created a few decades after the Bayeux Tapestry. The workshops often employed a very large number of people. 70 male and 42 female embroiderers worked on the execution of three ornate ceilings, which were commissioned for the first official appearance of the English Queen Philippa after the birth of the heir to the throne in 1330. The client provided the materials and paid the workers according to daily rates. The oldest known guild regulations, which regulate the work in such workshops, are those for the Paris embroidery guild from 1303. The regulations stipulated, among other things, that the stickers only work in daylight.

Individual differences in the way of embroidery became particularly clear when the back of the carpet was examined more closely in 1983. Some of the stickers executed their stitches in such a way that little thread length was used on the reverse side. You were previously likely working on assignments that used valuable gold thread. With other stickers, the embroidery method is much less economical. A work error at the interface between scene 13 and scene 14 is further evidence that the Bayeux Tapestry was executed by several people. At this point, it is not just the width of the upper border that does not match. On the left-hand side, the individual depictions of animals on the border are separated from each other by diagonal bars. To the right of this, pairs of animals are shown between the bars. It is even more noticeable that one of these inclined beams is missing at this transition point and suddenly three animal representations are found between two inclined beams. The error is not repeated at the other seams. Clear differences can also be found in the design of the stylized branches that accompany the sloping beams. The art historian Carola Hicks assumes that the design did not specify these, but that it was up to the individual stickers how they wanted to carry them out.

Place of origin

Many scholars believe that the tapestry was made in southern England before 1082. There are several indications for this. The combined representation of images with text is often documented in the late 11th century in Anglo-Saxon, Flemish and northern France, but not known from Norman origins before 1066. A number of details of individual scenes are inspired by Anglo-Saxon manuscripts from the 10th and 11th centuries. For example, there are visual parallels between the depictions of the Last Supper on the carpet and the depiction of the Last Supper in the Gospel Book of St. Augustine , which was located in St. Augustine's Abbey in Canterbury at the time of manufacture. The designer of the carpet also uses stylistic devices such as “pointing fingers”, “hunched shoulders” and “gesticulating figures”, which are based on the representations of the Utrecht Psalter and were prominent in southern England, particularly in Canterbury , in the 11th century. There was also a prestigious decorative embroidery school in Canterbury, the capital of Kent. The Latin inscriptions that accompany the scenes also contain orthographic forms of proper names that either do not correspond to the French spelling or directly to the English one.

Art historians who deviate from this consensus suggest a French place of origin. Due to the similarities between French works of art from this period and the Bayeux Tapestry, the art historian Wolfgang Grape believes it is possible that this work of textile art originated in the Bayeux area. The art historian George Beech suspects the Saint-Forent Abbey near the French city of Saumur as the place of origin.

style

The Bayeux Tapestry shows, among other things, ornamental art styles from the Viking Age. Characteristics of these styles can be found, for example, on the foliage of the first embroidered tree (scene 3), the dragon heads on the stems of the longships (scene 5 and scene 38) and the portico of scene 15. These are assigned to three Viking Age styles, namely the Mammen , Ringerike and Urnes styles , which developed from older Viking Age animal styles under continental Ottonian and late Anglo-Saxon influence from the end of the 10th century. The symmetrical depictions of animals in the border borders are influenced by Anglo-Saxon manuscripts as well as silk fabrics imported from Byzantium and Persia . The influence of the representations on these silks is probably more indirect, as they have already been copied in Ottonian scriptoria . The range of depicted animals and the way they are depicted, however, largely follows this artistic tradition and thus stands out clearly from the narrative in the main frieze.

Historical background of the events depicted

The aspirants to the English throne

In the main frieze of the Bayeux Tapestry, part of the power struggle for the English throne in the second half of the 11th century is the theme. The claim to this throne made by the Normans is derived from the marriage between the Anglo-Saxon King Æthelred II and Emma of Normandy in 991 . After Æthelred's death Emma, a daughter of the Norman Duke Richard I , married Canute the Great , who had ruled over a North Sea empire consisting of Denmark, England and Norway since the Battle of Assandun . From 1016 to 1042, England and Denmark were ruled by members of the Danish royal family in personal union. After King Hardiknut , a son of Emma and Canute the Great, died childless in 1042, his older stepbrother Eduard the Confessor , Emma's son by marriage to Æthelred, was proclaimed King of England. For the first time since 1016, a descendant of the Anglo-Saxon royal family ruled England. Eduard married Edith von Wessex , a daughter of Jarl Godwins and a member of one of the most influential Anglo-Saxon families in England. The marriage remained childless, so that there was no direct heir to the throne when Eduard died on January 5, 1066.

This power vacuum led to the appearance of four applicants for the English throne. The first two were Harald III. of Norway , who raised his claims as the successor of Canute the Great , and the Norman Duke Wilhelm II , whose inheritance claims ran through his great-aunt Emma of Normandy. The third contender was Edward's underage step-nephew, Edgar Ætheling . Edgar Ætheling, born in 1051, was the most legitimate contender for the English throne according to today's view. However, in the 11th century, primogeniture was not necessarily the normal way of succession. A man of royal descent could be appointed successor by the ruling king or elected to the throne by the Witan if the person entitled to inherit was too young or too weak. The fourth candidate, the Anglo-Saxon earl and brother-in-law of the late King Harald Godwinson , who was already equal to the king in power and wealth during Edward's lifetime, was elected King of England in this way after Edward's death.

The battle of Hastings

King Harald III of Norway invaded northern England in September 1066 to assert his claim to the English throne. He was defeated on September 25 at the Battle of Stamford Bridge by an army led by Harald Godwinson.

At the same time, the Norman Duke Wilhelm, with the blessing of Pope Alexander II, also recruited an invasion fleet to enforce his claims. However, unfavorable weather conditions prevented a crossing over the channel for several weeks, so that Duke Wilhelm and his troops did not reach the English south coast near Pevensey in Sussex until September 28, 1066 . The decisive battle between the Norman and Anglo-Saxon armies, the so-called Battle of Hastings , took place on October 14th. The fights remained undecided for a long time until Harald Godwinson fell victim to a Norman cavalry attack that evening. The Anglo-Saxon troops then fled the battlefield. The Norman Duke Wilhelm was crowned King of England on Christmas 1066.

Depiction of historical events on the Bayeux Tapestry

The main English characters on the Bayeux Tapestry are the aging King Edward and his brother-in-law Harald Godwinson, the Jarl of Wessex. " Jarl " is an old Germanic denomination, in English it is equated with Earl (dt. Graf). On the carpet, however, the title “ dux ” (Duke) is used for Harald Godwinson . The main characters on the Norman side are William, the Duke of Normandy and later King of England, and his half-brother Odo von Bayeux .

The Bayeux Tapestry is limited to depicting the power struggle between Harald Godwinson and Wilhelm, but in this context it also describes a number of events that are either incomprehensible today or seem insignificant compared to the main events.

Traditionally, the Bayeux Tapestry is seen as a work that justifies the Norman conquest of England. As early as the 19th century, however, people who dealt intensively with the Bayeux Tapestry pointed to the strikingly neutral depiction of the events in this painting. This neutral representation allows an interpretation of the representation from a Norman and Anglo-Saxon point of view.

The Bayeux Tapestry as a justification for the Norman campaign

From the Norman point of view, it is essential that Harald Godwinson wrongly ascended the English throne. The opening scene is therefore traditionally interpreted in such a way that King Edward instructs his brother-in-law Harald Godwinson to inform Wilhelm that he is the English heir to the throne. This view is supported by the Gesta Guillelmi Ducis , which was written between 1071 and 1077 by the Norman court chaplain William of Poitiers . To this day it is one of the essential sources about the life of William the Conqueror, but it cannot be regarded as an objective historiography.

On his journey to Normandy, Harald Godwinson ends up on the coast of the French county of Ponthieu , where Guido von Ponthieu takes him prisoner. Wilhelm buys him free, and after the common campaign in Normandy, he makes Harald Godwinson his vassal by handing over weapons.

An essential element for the Norman point of view is Harald Godwinson's perjury . With the oath , Harald recognized his loyalty to Wilhelm as a vassal . The oath followed a set ceremony in which the vassal uttered a formula in which he recognized the liege-giver as his master. Standing, he then swore his allegiance to either the Holy Scriptures or relics . The Bayeux Tapestry shows only the most important part of the ceremony in scene 23. The scene shows the enthroned Wilhelm on the left, pointing to the swearing Harald. Harald stands between two reliquary shrines and has placed his hands on both shrines to take the oath. Harald's right hand, which is visible to Wilhelm, shows the so-called horizontal benedicto gestus , the hand posture required when taking the oath. In this gesture of blessing , the thumb, index and middle fingers are stretched out, the other two fingers are bent back. In contrast, Harald's left hand, turned away from Wilhelm, rests informally on the reliquary. Harald thereby commits perjury. When Harald ascended the English throne in 1066, he apparently broke his vassal oath.

Several other details of the carpet seem to underscore Harald's unlawful accession to the throne. In scene 31 there is Archbishop Stigand next to the crowned Harald , which implies that Stigand had crowned Harald. Stigand had great influence in England and had brokered a peace between King Edward and Godwin of Wessex in 1052 . In the same year the Archbishop of Canterbury, Robert von Jumièges , was ostracized and Stigand was his successor. Pope Leo IX and his two successors, however, saw Robert as the rightful archbishop and refused to recognize Stigand. It was not until 1058 that he received the pallium from the antipope Benedict X , but the following year he himself was deposed and excommunicated . A coronation by Stigand, of which several Norman historians report, would have been an illegitimate coronation.

The portrayal of Harald's death is also interpreted in more recent interpretations to support the Norman reading: symbolized by the arrow that hits him in the eye, God punishes Harald for his perjury and robbing the throne. Then he is slain by a Norman horseman and suffers death.

The Anglo-Saxon reading of the carpet

The opening scene, in which, according to the traditional interpretation, King Edward instructs his brother-in-law to confirm Wilhelm's succession to the throne, can also be interpreted differently from an Anglo-Saxon point of view:

It is likely that Edward in 1051 promised Wilhelm the succession to the throne; However, this happened in the short period in which Edward had succeeded in disempowering the Godwin family and it was not yet clear that there was Eduard Ætheling, a heir to the throne from the Anglo-Saxon royal family. In the early 1060s, however, the situation was completely different. Edgar Ætheling , the son of Eduard Ætheling, lived on at the English court and the Godwin family had regained their old influence. Unless Harald Godwinson's ambitions were aimed directly at the English throne, it was likely that he would be the reign of the underage Edgar Ætheling. From this point of view, it is implausible that King Edward asked his brother-in-law Harald to instruct William of the succession to the throne. According to this reading, the aim of the crossing over the canal is Harald's attempt to free his brother Wulfnoth and his nephew Hakon from being held hostage by the Norman . These were presumably given to the Duke as hostages in 1052 when King Edward William promised the Crown of England. The English chronicler William of Malmesbury , who wrote at the beginning of the 12th century, even claims that Harald ended up on a fishing trip to the French coast. The oath scene after the Breton campaign also indicates that Harald Godwinson takes the oath under duress. If Duke Wilhelm was the heir to the throne desired by King Edward, then there is little reason for Harald Godwinson's repentant attitude in the second meeting with King Edward. It is more understandable when Harald swore a vassal oath to Wilhelm, even though he knew that King Edward wanted him as his successor. That Harald was the chosen successor is also indicated by the death scene of King Edward and the following scene in which Harald is offered the crown. The dying scene is headed with the words "This is where King Edward speaks to his faithful" , and the sitters can be interpreted in such a way that Harald was among them. The next gesture shows that he does not reach for the crown hungry for power. The man who offers it to him points with one hand at the dying Edward. Harald, on the other hand, is depicted as hesitant to accept the crown.

The positive portrayal of Harald Godwinson in several other places on the carpet is striking. The title Dux Anglorum (Duke of the English), which is added to him in the first scenes of the tapestry, underlines his high position in England. In scene 17, he courageously saves two Normans who got caught in quicksand off Mont-Saint-Michel . Harald Godwinson is later referred to as Rex (King) in the appropriate places , and he eventually dies a heroic death.

The individual scenes of the main frieze

The plot is told in a main frieze about 32 centimeters high. The reading direction of this frieze is basically in the usual reading direction from left to right. In the case of two events, however, the reading direction is deliberately reversed. The delivery of Harald Godwinson to Wilhelm by Count Wido is told in the sequence of scenes 12, 11, 10 and 13. The death of King Edward and his funeral are reported in scenes 27, 28 and 26. Changes of scene are marked by the representation of trees, towers or the change between land and water. The scenes are packed differently in terms of content: the crossing of the canal shown in scene 38 takes up a much wider space compared to other scenes. The main frieze is accompanied by a descriptive Latin text that explains the plot.

The storyline is easy to understand. However, scene 15 remains mysterious, in which a nobly dressed woman named Ælfgyva is touched by a priest. It is not clear whether he is stroking her tenderly or slapping her face. In the inscription belonging to the scene the verb is missing. Translated it means where a priest and Ælfgyva . It seems fairly certain that this cautious presentation indicated a scandal that was well known at the time. The naked man in the lower border, who is depicted in an obscene pose and with the movement of his left arm, seems to imitate the movement of the priest and at the same time seems to reach lfgyva under the dress, indicates a sexual character of the scandal.

One of the few scenes on the tapestry that, as far as we know today, does not correspond to the facts is scene 18. Count Conan of Brittany was in a dispute with some Breton rebels in 1064. One of them, Riwallon von Dol, asked Duke Wilhelm for help. For this reason, Duke Wilhelm attacked the city of Dol on his Breton campaign. Scene 18 shows Count Conan fleeing the fortress with the help of a rope. However, this representation is incorrect because Conan had not yet captured Dol Castle. Conan was forced to give up the siege by Wilhelm's army, but only moved away.

Sequence of scenes

- Scene 1: Meeting between Eduard the Confessor and Jarl Harald Godwinson.

- Scene 2: On his journey to the coast, Harald brings along a hunting falcon and a pack of hunting dogs.

- Scene 3: Harald prays in Bosham Church for God's help for the journey. The travelers take their last meal ashore.

- Scene 4 and Scene 5: crossing to France; unfavorable winds force Harald to make an emergency landing on the coast, which belongs to the land of Count Guido von Ponthieu . In the main frieze, the count is referred to as Wido.

- Scene 6: The English go ashore.

- Scene 7: Guido von Ponthieu orders his people to take Harald prisoner.

- Scene 8: Guido von Ponthieu leads the prisoners to his castle.

- Scene 9: Guido von Ponthieu and Harald Godwinson in conversation.

- Scene 10: Wilhelm's messengers seek out Guido von Ponthieu.

- Scene 11: Armed horsemen gallop to Beaurain.

- Scene 12: Messengers inform Wilhelm about Harald's situation.

- Scene 13: Guido von Ponthieu delivers Harald to Wilhelm.

- Scene 14: Wilhelm, accompanied by Harald Godwinsons, goes to his castle.

- Scene 15: A woman and a priest are shown. It is not known which event the scene alludes to.

- Scene 16: Harald Godwinson and Wilhelm go to war against the Count of Brittany.

- Scene 17: Men and horses get caught in quicksand while crossing a river. Harald saves some of the men.

- Scene 18: The Norman army advances to Dol. Count Conan of Brittany flees.

- Scene 19: Attack on Dinan.

- Scene 20: The city of Conan surrenders.

- Scene 21: Wilhelm makes Harald Godwinson his vassal.

- Scene 22: Wilhelm and Harald Godwinson arrive in Bayeux.

- Scene 23: Harald Godwinson swears the vassal oath to Wilhelm.

- Scene 24: Harald Godwinson sails back to England, where his return is expected.

- Scene 25: Harald Godwinson meets King Edward again.

- Scene 26: Edward is buried one day after his death in the Church of St. Peter the Apostle (Westminster Abbey). A man in the process of installing a weathercock and the blessing hand of God over the church indicate that the funeral took place shortly after the church was dedicated on December 28, 1065.

- Scene 27: King Edward on his deathbed.

- Scene 28: King Edward is being prepared for his funeral.

- Scene 29: Harald Godwinson accepts the royal crown.

- Scene 30 and Scene 31: Harald Godwinson sits on the English royal throne, Archbishop Stigant is standing on his left.

- Scene 32 and 33: Some men point to a comet that is now identified as Halley's Comet.

- Scene 34: A ship lands on the French coast to inform William of the death of King Edward.

- Scene 35: Wilhelm orders ships to be built.

- Scene 36: Ships are launched.

- Scene 37: Chain mail, weapons and wine are brought to the ships.

- Scene 38: Wilhelm’s fleet is on its way.

- Scene 39: Horses are led ashore by men.

- Scene 40: Soldiers ride to Hastings to get food.

- Scene 41: One of Wilhelm's followers monitors the procurement of provisions.

- Scene 42 and Scene 43: Meat is being prepared.

- Scene 44: Bishop Odo blesses food and drinks.

- Scene 45: A fort is being built in Hastings.

- Scene 46 and Scene 47: The events before the battle; Wilhelm is briefed by a scout, a house is set on fire, a woman flees with a boy.

- Scene 48: The Normans advance in order of battle.

- Scene 49: Wilhelm is informed by spies that the English army is near.

- Scene 50: Harald Godwinson is warned about the Norman army by scouts.

- Scene 51: Wilhelm tells his men to fight bravely.

- Scene 52: Two of Harald Godwin's brothers are killed in battle

- Scene 53: The battle is indicated by falling horses.

- Scene 54: Bishop Odo of Bayeux encourages the Norman army.

- Scene 55: When the rumor that he was killed in battle, Wilhelm pushes his helmet behind his neck.

- Scene 56: Harald Godwinson's army is smashed.

- Scene 57: Harald is killed in battle.

- Scene 58: The English flee.

The edging

The main frieze is bordered over most of the length of fabric by two edging borders, each around nine centimeters high. The entrance scene is also surrounded by a border on the left. The border borders depict, among other things, animals, plants, people, fable scenes and fabulous animals that have a variety of connections to the events on the main frieze. They are separated from each other by diagonal bars and occasionally also by stylized branches, so that the border borders have an ornamental character. Individual fable scenes can be clearly assigned to Aesopian fables , such as the fable of the fox and the raven , the plot of which is taken up three times. For others, the assignment is controversial. There is no consensus on the extent to which the fables constitute a commentary on the plot. Among the ships that show Harald's crossing to the French coast is, for example, an illustration of Aesop's fable of the monkey who, in the name of the animals, asks the lion to become their king. A reference to the plot seems obvious here.

430 animals are shown as symmetrical pairs, either facing each other or facing the back. Birds are most often depicted. A pair of cocks and two pairs of peacocks can be clearly identified . The other birds cannot be clearly assigned to a specific species, but are reminiscent of geese , pigeons or cranes . All have excessively large feet, and often one or even two of the wings are extended. Lions are also often depicted in the border. Many have a mane, the maneless ones are certainly lionesses as they are embroidered in a similar way. Comparable lion representations can be found in numerous Anglo-Saxon manuscripts and are one of the most popular motifs of the Canterbury School even after the Norman conquest of England. In the border borders there are also two camel representations, which may have been taken over from imported silk fabrics. This could also have inspired the griffin depictions on the Bayeux Tapestry, which are not found in Anglo-Saxon manuscripts.

Some of the representations in the border borders indicate the season of the year, the length of a period or comment on the actions of the main frieze. Scene 10 shows peasants plowing and sowing in the lower border, which suggests that Count Guido von Ponthieu met Wilhelm's messengers in spring. The majestic appearance of the English King Edward sitting on a chair decorated with lion heads in scene 1 is exaggerated by a floral motif flanked by lions in the upper border. In the lower border sit two birds, also flanked by a pair of lions, cleaning their plumage. In some cases the main frieze protrudes into the border. This is the case, for example, in scene 38, in which the sails of the Norman ships reach to the edge of the fabric. On the last scenes of the tapestry depicting the Battle of Hastings, the lower border also serves to depict archers, dead and wounded and the looting of the fallen.

Features of the presentation

Body language and gestures

Individual scenes are shown in the perspective of meaning , that is, the size and orientation of the people shown in the picture depends on their meaning: important protagonists appear large, less important ones are shown smaller, even if they are spatially in front of the other person. This is noticeable in scene 1, where Harald Godwinson, standing to the left of King Edward, who is depicted en face, is deliberately depicted much smaller.

The figures appear thin and narrow, the legs are long in proportion to the body and the heads are small. What is striking in many of the scenes is the concise body language of the characters, which clearly differs from the calm charisma of sacred images of this time. Similar to sacred pictures, the chosen posture is not accidental; Posture details reveal how the rug designer interpreted and understood the events. This can be seen very well in scene 25, the scene in which Harald, returning home from Normandy, is received by King Edward. Compared to scene 1, Edward's face is older; in his left hand he is holding a walking stick. Harald approaches him with bent knees and hunched shoulders, a posture that signals guilt. A man standing behind him, the corners of his mouth drawn down, points with an outstretched forefinger to Harald standing so humbly in front of Edward.

Pointing fingers, the direction of the face and the rotation of the body often drive the action, and pointing gestures often emphasize the special meaning of individual scenes. For example, several people point to the swearing Harald. The gestures of the hands are also often essential for an understanding of the scenes. The fact that King Edward gives his brother-in-law Harald an order in scene 1 can be seen from the slightly bent index finger of his right hand, which rests on Harald's. Harald accepts the order. This becomes clear through the acclamation gesture of his left hand, in which the open hand is turned towards the viewer with an extended index finger. In scene 3 Harald has his last meal before crossing the canal and is absorbed in a conversation with an unknown man. The hand gestures indicate that this is not a normal table conversation. Harald speaks seriously to his counterpart and underlines the meaning of his words with the pointing finger of his hand. Some scientists attach particular importance to the inconspicuous round object that is located between the two people. A circle is often to be interpreted as a sacred symbol. The circle is taken up in the border below the scene. There is a scene from the Aesopian fable of the fox and raven. The object that falls out of the raven's beak resembles the object that lies in front of Harald in the scene. This is sometimes interpreted as an indication that the conversation is about succession. In scene 27, the scene showing Edward dying, the hands of the four characters form an oval. Among others, Harald and a clergyman who can be identified by the tonsure are present. Queen Edith, seated at the foot end, points to this oval with her right hand. The curtain is drawn up over the oval and the ends of the curtains, which are wound around the columns, end in an acanthus leaf . Both are an indication that a sacred act is taking place here.

Hairstyles and costume

Anglo-Saxons and Normans can be distinguished in many scenes by their different hairstyles. Characteristic of the Anglo-Saxons is a thin mustache and a hairstyle in which the hair reaches below the ears. The Normans are beardless and the neck is shaved up. In scene 24, on the other hand, in which Harald Godwin's return to England is shown, the Anglo-Saxons no longer wear mustaches either. It can no longer be clarified today whether the influence of French fashion is to be shown here or whether it is a failure of the designer. In later scenes, Anglo-Saxons are apparently portrayed arbitrarily with and without a mustache.

The difference in clothing between Normans and Anglo-Saxons is noticeable on closer inspection. In Anglo-Saxons, the doublet cut wide at the bottom ends above the knees. The overgarment of the Normans ends below the knees, closes at the lower end with a wide border or with fringes and the cut follows the leg contours more closely. Some of the Normans have ribbons running across their legs on the depictions. The garters in the first depiction of William the Conqueror on the tapestry (scene 12) are particularly striking . Here the garters have wide tassels.

There are only three depictions of women on the entire carpet, so that much less can be said about women's costumes. Ælfgyva in scene 15 and the woman running out of the burning house in scene 47 wear coats or smocks with long sleeves. It is not possible to tell whether Queen Edith is wearing a similar robe in scene 27, as she is shown huddled. However, all three women have their heads covered, indicating that they are married.

Edward, Wilhelm and Harald wear ankle-length, pleated robes in some scenes; Harald is dressed in it when he is wearing the English royal crown (scenes 30 and 33). Wilhelm's lordly role is also underlined by such a garment in the scene in which he takes Harald's vassal oath (scene 23). Coats seem to symbolize power and influence in a similar way, but the number of coat wearers is greater. For example, in scene 2, when Harald sets off on his journey, the entire mounted entourage wears coats. In most representations, the coats are held together by a fibula on the right shoulder. Wilhelm's coat is particularly splendid in scene 13, in which Harald is led to him; the bright red robe has decorative borders below and on the front. Two ribbons with decorated ends that flutter backwards from the neck collar are striking. There is a depiction of Canute the Great around fifty years older, which has similar bands. This, too, is interpreted to mean that Wilhelm is portrayed as the rightful successor to the English throne at a very early stage.

Weapons, saddles and tools

The Bayeux Tapestry reveals what weapons were used and how they were used. Swords are only worn by members of the upper class. It was used as a cutting weapon, which is particularly evident in scene 57, in which Harald Godwinson is killed by a Norman horseman. The sword is also a symbol of power. This is indicated by the scenes in which Harald, seated on the ducal throne, holds his sword like a scepter with the point pointing upwards (e.g. scene 12). In scene 9, the Count of Ponthieu also receives Harald in this pose. Harald has to hand over his sword there - a clear sign of the loss of his power. The scenes also reveal how swords were wielded. According to the representations in scene 9, swords were attached to the belt with two belt clasps or with a belt loop and a clasp.

Axes are used as a melee weapon, and the long-shafted battle ax is a symbol of dignity. It is more characteristic of Anglo-Saxons than of their Norman contemporaries. Various types of axes are also shown in scene 35. This scene is of great importance in understanding the use of tools in medieval times. Long-shafted axes are used to fell the trees, with the branches being cut before the trees are felled. The individual planks are smoothed with T-shaped axes, and an illustration shows how a raw board is clamped in a split tree trunk to make it easier to work on.

All of the saddles depicted on the tapestry have a high bow and spike . In scene 10, a short man marked by the name Thurold holds two saddled, riderless horses, on which it can be clearly seen that the saddle girth is buckled on the side and fastened under the saddle with rivets. The stirrup leathers are adjustable, the riders are usually only shown with their legs slightly pulled up. The reins consist of two straps. In one of the horses in scene 10, these are held together with buttons or bars below the horse's jaw and towards the rider's hand. The riders wear spurs with spikes on their feet . Wheel spurs only became known later in the Middle Ages.

Ships

There are no remains of any kind that indicate shipping between England and Normandy. The carpet proves to be an extremely helpful source if an attempt is to be made to reproduce northern European shipping.

Ship scenes are dominant on the carpet. Even the shipbuilding of the Norman fleet is illustrated; in scenes 35 and 36 you can see the trees being felled with the help of axes. In the next step, the trunks are cut into planks with a bearded ax. Scene 36 shows the final phase of shipbuilding; holes are pre-drilled, rivets are driven in to connect the planks and the protruding parts of the rivets are cut off. The different colored planks could be an indication of the brick construction.

King Wilhelm's fleet probably consisted of war and transport ships. In addition, small accompanying ships can be seen that were towed by the fleet. There are also those without oar holes, which indicates a function as a cargo ship. The main features of boat and ship are, however, identical throughout. There are kite-like or figurative attachments on the stern, which are typical of Viking shipbuilding. It can be observed here that on the Anglo-Saxon ships they face outwards (scenes 4 and 5) - in contrast to the Norman ships, which is intended to underline the differences between the two empires and their construction methods.

At the gunwale of the ships lined up shields are attached (Scene 24/38) so that they overlap. However, the method of attachment and possible function of the display remain unclear. Using earlier examples, the Skuldelev ship (early 11th century) and the Gokstad ship (9th century), it can be proven that the shields were actually attached to the outside of the ship's side, which does not mean that it was the same here . There are also a few large shields at the ends of the stern, which may have been used to identify the fleet and its crew, as they are provided with patterns. The sails of the ships are shown in a triangular shape, which is in contrast to the actually square sail shape. Presumably the artist did not have the means to depict an optical foreshortening. The Scandinavians may have been making patterned sails as early as the 10th century. But the exact appearance of the sails is difficult to reconstruct, as the sails have seldom been preserved. In this context, too, the carpet is often used as a comparison.

Possible client of the carpet

The client of the Bayeux Tapestry and his intention when awarding the contract are unknown. Local tradition attributed the carpet to Wilhelm's wife Mathilde von Flandern , who was said to have embroidered it together with her ladies-in-waiting in order to record her husband's victory. This was questioned as early as the early 19th century. Demanding textile work was done in the household of a queen. Due to the dimension of the work and the narrative style, Mathilde is rejected as the author of the work in today's literature. There is broad consensus that this is a commissioned piece of work that has been done in a professional workshop. The art historian George Beech is one of the few who would consider Queen Mathilde to commission the carpet. However, the most likely client is Wilhelm's half-brother Odo von Bayeux . In addition, the French nobleman Eustace II of Boulogne and Edith von Wessex , widow of King Eduard and sister of Harald Godwinson, are discussed as possible clients.

Odo of Bayeux

Duke William came from an extramarital relationship of the Norman Duke Robert I the Lohgerbertochter Herleva . Shortly after the birth of the second child from this relationship, Herleva was married to Herluin von Conteville , a feudal husband of Duke Robert. From this marriage comes Odo von Bayeux, who owed his half-brother Wilhelm, among other things, the bishopric of Bayeux. After the conquest of England, the bishop, described by contemporary sources as ambitious and vain, received the county of Kent and became the most powerful and richest noble landowner in England. Canterbury, which, according to many art historians, is where the carpet was made, also belonged to his immediate sphere of influence.

Odo von Bayeux is considered to be one of the possible commissioners of the carpet, since he played a greater role in the battle than contemporary sources attribute to him. He appears in four crucial scenes of the portrayal and is named in three scenes. During the deliberations before the invasion of England he advises Duke Wilhelm, at the meal after landing in Pevensey he speaks the blessing, he dominates the council of war before the Battle of Hastings, and in the decisive scenes of the battle he is the one who joins the Norman army Attack encouraged. Connections can also be made to at least two other, more obscure people who are named on the carpet. The Domesday Book shows that two men named Wadard and Vital, respectively, were feudal men of the bishop who received land in Kent after the conquest of England.

The commission of Bishop Odo provides a plausible explanation of how the carpet came into the possession of Bayeux Cathedral . Due to the secular nature of the carpet, however, it is unlikely that the carpet was originally intended as an ornament for the cathedral, which was inaugurated in 1077. Due to the neutral presentation of the events, it is assumed that the designer was close to the Anglo-Saxon side and that this is why the carpet has this ambiguity.

Eustace of Boulogne

In addition to Duke Wilhelm and Bishop Odo, the Bayeux Tapestry explicitly highlights Eustace of Boulogne by naming him in its battle scenes. Count Eustace was not a Norman, but French, and commanded the right wing, which consisted of French and Flemish fighters, at the Battle of Hastings. He was descended from Charlemagne on both his father's and mother's side , but not in a direct male line. His Carolingian descent and membership of the French aristocracy is also emphasized by the contemporary chronicles. His first marriage was to Godgifu, a sister of the English King Edward. However, the marriage remained without descendants, and Godgifu died before 1049. It is no longer understandable today why Count Eustace decided to support Duke Wilhelm in his campaign of conquest. Decades of disputes between the count and the Godwin family, which Harald Godwinson now provided the English king, could have played a role. However, Duke Wilhelm seems to have had doubts about the reliability of his alliance partner. As a pledge for his good conduct during the Norman campaign, Count Eustace had to leave his son hostage in Bayeux.

The contemporary sources attribute different weight to Count Eustace in the Battle of Hastings. William of Poitiers claims that Count Eustace urged Duke Wilhelm to retreat during the battle and that he was wounded in the back while escaping from the battlefield. Carmen de Hastingae Proelio , created shortly after the battle, tells of Count Eustace as one of the heroes of the battle, who saved Wilhelm's life in the turmoil and made his horse available to him after Wilhelm was killed.

If Count Eustace was the commissioner of the carpet, it was probably a reconciliation gift to Odo von Bayeux. In 1067, the count made the mistake of attacking Dover, which was part of Bishop Odo's domain. The attack was unsuccessful, Count Eustace fled to Boulogne and was stripped of his English possessions by King William. It was not until the 1070s that there was reconciliation between Count Eustace, King Wilhelm and Bishop Odo. This scenario provides a plausible explanation as to why Bishop Odo is so highlighted on the carpet, and also explains the mention of Count Eustace. As an explanation for the neutral representation of the events, as with Odo von Bayeux, one must fall back on the fact that a designer of the carpet close to the Anglo-Saxon side gave it its neutrality.

Edith from Wessex

Duke Wilhelm was crowned King of England on Christmas Day 1066, but at that time he had only conquered parts of England and between 1067 and 1072 had to assert his claim to the English throne not only against further Scandinavian attacks, but also against English rebels. His behavior during these years was marked by a strong distrust of the established Anglo-Saxon nobility. The English chronicler William of Malmesbury wrote of this period that he robbed the most influential Englishmen of their income first, then of their land and some of them also of their lives. The Domesday Book shows that the Anglo-Saxon king widow Edith von Wessex was largely spared as one of the few exceptions to this Norman conquest. They kept their lands in Wessex , Buckinghamshire , East Anglia and the Midlands . In view of the fact that after his accession to the throne King Edward did not hesitate to confiscate the lands of his mother, the king's widow Emma of Normandy , the generosity of Wilhelm towards the widow of his predecessor and sister of his opponent Harald Godwinson is remarkable. Edith of Wessex was also the most influential member of the Godwin family after four of her brothers died in the battles of 1066 and their only surviving brother, Wulfnoth, was held hostage by the Norman.

Contemporary chronicles describe Edith von Wessex as an unusually educated woman who exercised great influence in the last few years of her husband's reign. Shortly after Wilhelm's coronation, she negotiated a peaceful settlement for the city of Winchester with the new English king and played her part in paying tribute to Wilhelm. As a direct reward for her support, Wilhelm gave her the right to keep her widow's residence in Winchester. The chronicler Wilhelm von Poitiers also expressly emphasizes their support for Wilhelm after his coronation. Edith von Wessex as well as Bishop Odo or Count Eustace cannot be proven as the commissioner of the Bayeux Tapestry. As such, however, it comes into question because it would conclusively explain the neutral depiction of the Norman conquest on the Bayeux Tapestry. She herself is depicted on Edward's deathbed, and the Bayeux Tapestry not only records the death of her brother Harald, but also that of her brothers Gyrth and Leofwine Godwinson . It is also possible that the bearded man depicted in scene 14 together with Harald Godwinson and Wilhelm is her brother Wulfnoth. Since Edith von Wessex died in 1075, she would have commissioned the carpet during a period in which Odo of Bayeux was exercising a power in England equal to that of a viceroy. This would explain why Odo von Bayeux is so prominently featured on the carpet. Count Eustace was her brother-in-law, so this family connection would also explain his naming. As queen, she had administered the royal wardrobe and therefore had connections to numerous monasteries that carried out such textile work. She is also verifiably the client of the Vita Ædwardi Regis , the life story of her husband, in which the achievements of her father Godwin von Wessex play a large part. What is particularly striking here is the similarity between the depiction of the death scene on the Bayeux Tapestry and the depiction of the last hours in the Vita Ædwardi Regis . With this in mind, it seems possible that Edith von Wessex also commissioned the Bayeux Tapestry.

Storage and reception history

Middle Ages to French Revolution

The oldest evidence that can be interpreted as a reference to the Bayeux Tapestry is a poem written between 1099 and 1102 by Abbot Balderich von Bourgueil , dedicated to Adela von Blois , daughter of Wilhelm. Part of the poem describes in detail a wall hanging in the chamber of the king's daughter, and the sequence of scenes described in this wall hanging can also be found on the Bayeux Tapestry. The pictorial work described is certainly not identical to the Bayeux Tapestry, since the abbot speaks of a wall hanging made of gold, silver and silk and the Bayeux Tapestry would have been too big for a chamber. It is possible that Wilhelm’s daughter actually owned a small copy of the Bayeux Tapestry made in finer materials. However, this description may also have been a literary device of the abbot, who then knew the Bayeux Tapestry very well.

The oldest clear references to the Bayeux Tapestry can be found in a directory of the Notre-Dame de Bayeux Cathedral from 1476. This is where the first mention is made that the tapestry was hung annually in the nave. For the next 250 years after 1476, no written mentions are known, it was not until the beginning of the 18th century that attention was drawn to the carpet again. In the estate of Nicolas-Joseph Foucault , a former director of Normandy, who bequeathed his papers to the Bibliothèque du Roi, there was a stylized drawing of the first carpet scenes. In 1724 a scientist by the name of Antoine Lancelot drew the attention of the Académie Royale des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres to this drawing and a little later published an article in the Academy's journal with a reproduction of the drawing. The Benedictine monk and scientist Bernard de Montfaucon finally managed to find the model for the drawing. Montfaucon also arranged for a draftsman to copy the subsequent scenes, and in 1729 published the opening scenes in the first volume of Les Monuments de la Monarchie française and the remaining scenes in the second volume, published in 1732. Montfaucon also reported that, according to local tradition, the carpet was embroidered by Wilhelm's wife Mathilde .

The carpet was almost lost during the French Revolution : in 1792, the intervention of Bayeux City Councilor Lambert Léonard-Leforestier prevented the carpet from being used as a tarpaulin for a wagon that was supposed to transport goods to a military warehouse. Two years later, an art commission that had recently been set up in Bayeux saved the carpet from being cut into pieces and used as decoration for a festival day.

19th century

In 1803, Napoleon Bonaparte , who at the time was still planning an invasion of Great Britain, placed the carpet on display in the Louvre . In 1804 the Paris tapestry returned to Bayeux and was kept there in different places, but was no longer exhibited in the cathedral. The carpet was seriously damaged when it was rolled up on two cylinders for a while, in order to show individual sections by rolling the cylinder up and down, similar to a Chinese scroll painting. Between 1818 and 1820 the English draftsman Charles Alfred Stothard made a colored copy of the carpet on behalf of the antiquarian society of London and, through his careful examination of the carpet, created the basis for the restoration of the damaged areas. In 1842 the back of the tapestry was re-lined and the carpet was shown behind glass in a separate room in the Bayeux Public Library. The linen used for feeding is probably what is still available today. In the mid-1880s, a group of English women led by textile artist Elizabeth Wardle made a copy of the rug, which has been on display in Reading since 1895 . The copy, which the forty women worked on for around two years, is largely true to the original. In accordance with the moral code of the Victorian Age, however, the English women censored the explicit representation of male genitals, which are located in some places in the edge of the original.

The audience's reactions to the carpet were always very divided. The English art historian and painter John Ruskin described it as fascinating. Charles Dickens, on the other hand, found it to be the work of very limited amateurs.

20th century

After the start of the Second World War in 1939, the carpet was initially kept in a bunker under the Bishop's Palace in Bayeux. After German troops occupied large parts of France in 1940, the Forschungsgemeinschaft Deutsches Ahnenerbe e. V. , an ideological research institution of the National Socialists , interested in the carpet, which from their point of view primarily celebrated the fighting power of Nordic peoples and thus seemed suitable to provide evidence of the alleged superiority of the " Aryan race ". The research group headed by Herbert Jankuhn had the carpet first brought to the Abbey of Juyae-Mondaye in order to be able to examine and photograph it better. In 1941 the carpet was moved to an art depot near Le Mans . The carpet stayed there until 1944, when it was probably brought to Paris on the orders of Heinrich Himmler and deposited in a cellar of the Louvre to protect it from war damage. On August 21, 1944, SS officers also tried, on Himmler's orders, to get the carpet out of the Louvre and bring it to Berlin. However, the streets around the Louvre were already in the hands of French resistance fighters at the time, so the carpet remained there. After the liberation of Paris , towards the end of 1944, it was on public display for a month in the Salle des Primitifs des Louvres. The carpet did not return to Bayeux until 1945. On June 6, 1948, the 4th anniversary of the Allied invasion , the exhibition room in the old bishop's court was inaugurated.

The inclusion of the Bayeux Tapestry in the World Heritage Document in 2007 underscores the importance attached to this work of textile art today. The importance of the carpet is due to the fact that very few comparable works of textile art from the early Middle Ages have survived. Due to this lack, it cannot be clarified whether the Bayeux Tapestry was classified by contemporary viewers as an outstanding work or as a more everyday work.

21st century

According to a decision by French President Emmanuel Macron , the carpet is to be loaned to England for an exhibition after extensive restoration work is still planned. However, this political gesture of goodwill towards Great Britain has caused unease among the experts, as no one can yet say whether such a fragile work of art can be transported unscathed.

The whole carpet

literature

- Andrew Bridgeford: 1066, The Hidden History of the Bayeux Tapestry. London 2004, ISBN 1-84115-040-1 .

- Meredith Clermont-Ferrand: Anglo-Saxon Propaganda in the Bayeux Tapestry. Edwin Mellen Press , Queenston (Ontario) 2004, ISBN 0-7734-6385-2 .

- John Michael Crafton: The Political Artistry of the Bayeux Tapestry. Edwin Mellen Press, Queenston (Ontario) 2007, ISBN 978-0-7734-5318-0 .

- Martin K. Foys: The Bayeux Tapestry on CD-ROM. Scholarly Digital Editions, Boydell & Brewer, Woodbridge 2002, ISBN 0-9539610-4-4 .

- Carola Hicks: The Bayeux Tapestry - The Life Story of a Masterpiece. Vintage Books, London 2007, ISBN 978-0-09-945019-1 .

- Mogens Rud: The Bayeux Tapestry and the Battle of Hastings. 1st edition, 1st edition. Christjan Eljers, Copenhagen 1992, ISBN 87-7241-697-1 .

- Egon Wamers (Ed.): The Last Vikings - The Bayeux Tapestry and Archeology. Archaeological Museum Frankfurt am Main, Frankfurt am Main 2009, ISBN 978-3-88270-506-5 .

- David M. Wilson: The Bayeux Tapestry. Parkland, Cologne 2003, ISBN 3-89340-040-0 . (Reprint / special edition of the OA from Ullstein / Propylaen Verlag from 1985)

Video

The following video provides an overall view of the Bayeux Tapestry.

Web links

- Full length carpet

- Video: Animated version of the carpet

- The Bayeux Tapestry in full length (Bibliotheca Augustana, 8MB)

- Video: "The Bayeux Tapestry - all of it, from start to finish" Explanation of the image program by Youtuber "Lindybeige" (English)

- "Historic Tale Construction Kit" web-based program for creating your own sequence of images from the motifs of the carpet

- Barbara Denscher: The Bayeux Tapestry - Made in Denmark In: Flaneurin

Individual evidence

- ↑ Wamers et al., P. 6.

- ↑ Wamers et al., P. 18.

- ↑ Bayeux Tapestry. In: Memory of the World - Register. UNESCO , 2007, accessed July 5, 2013 .

- ↑ Hicks, p. 40.

- ↑ a b Wamers et al., P. 16.

- ^ Wilson, p. 9.

- ↑ Rud, p. 13.

- ↑ Crafton, p. 13.

- ↑ a b Hicks, p. 19.

- ↑ Hicks, p. 51.

- ↑ Wamers, p. 16.

- ↑ a b Hicks, p. 48.

- ↑ a b Hicks, p. 41.

- ↑ a b Wilson, p. 10.

- ↑ a b Hicks, p. 42.

- ↑ Rud, p. 11 and p. 12.

- ^ Wilson, pp. 9 to 13.

- ↑ Hicks, p. 43 and p. 44.

- ↑ a b Rud, p. 12.

- ↑ Rud, p. 11.

- ↑ Hicks, p. 44.

- ↑ a b S. Hicks, 45 and p. 46.

- ↑ Hicks, p. 47.

- ↑ Hicks, p. 52 and p. 53.

- ↑ Hicks, pp. 49 and 50

- ↑ Hicks, p. 49.

- ↑ Hicks, p. 50.

- ^ Wilson, p. 12.

- ↑ a b Rud, p. 10.

- ↑ Rud, p. 10 and p. 11.

- ↑ Crafton, p. 16.

- ↑ Wamers et al., P. 34.

- ↑ a b c d Carola Hicks: Animals in Early Medieval Art. Edinburgh University Press, Edinburgh 1993, ISBN 0-7486-0428-6 , p. 252.

- ↑ Wamers et al., P. 44.

- ^ Bridgeford, pp. 54 to 56.

- ^ Wilson, pp. 14 and 15.

- ↑ Clermont-Ferrand, p. 3.

- ↑ Rud, p. 9.

- ^ Bridgeford, p. 21 and p. 22.

- ^ Bridgeford, p. 62.

- ^ Wilson, p. 180.

- ↑ Wamers et al., P. 24.

- ^ Bridgeford, p. 107 and p. 108.

- ↑ Wamers et al., P. 26.

- ^ Bridgeford, pp. 53 and 54.

- ^ Bridgeford, p. 56.

- ↑ Rud, p. 25.

- ↑ Rud, p. 38 and p. 39.

- ↑ Hicks, p. 10.

- ↑ Hicks, p. 10 and p. 11.

- ↑ Rud, p. 58.

- ^ Wilson, p. 16.

- ↑ a b Wamers et al., P. 20.

- ^ Wilson, pp. 17 and 18.

- ↑ Rud, p. 50.

- ^ Wilson, p. 175 and p. 179.

- ↑ Rud, p. 40.

- ^ A b Carola Hicks: Animals in Early Medieval Art. Edinburgh University Press, Edinburgh 1993, ISBN 0-7486-0428-6 , p. 253.

- ^ A b c Carola Hicks: Animals in Early Medieval Art. Edinburgh University Press, Edinburgh 1993, ISBN 0-7486-0428-6 , p. 254.

- ^ Wilson, p. 11.

- ↑ Wamers et al., P. 48.

- ↑ Wamers et al., P. 56.

- ↑ Wamers et al., P. 53.

- ↑ Wamers et al., P. 22.

- ↑ a b Wamers et al., P. 50.

- ↑ Wamers et al., P. 58.

- ↑ Rud, p. 55.

- ↑ Rud, p. 47.

- ↑ Wamers et al., P. 60.

- ↑ Wamers et al., P. 64.

- ^ Cover picture of the Liber Vitae des New Minster in Winchester

- ↑ Wamers et al., P. 62.

- ↑ Wamers et al., P. 72.

- ↑ a b Wilson, p. 176.

- ↑ Rud, p. 44.

- ^ Wilson, p. 184.

- ^ Wilson, p. 177.

- ↑ Rud, p. 42.

- ^ Bridgeford, p. 162.

- ↑ Crafton, p. 10 and p. 11.

- ↑ Clermont-Ferrand, p. 4.

- ↑ Hicks, p. 23.

- ↑ Hicks, p. 22.

- ↑ a b Bridgeford, p. 163.

- ↑ see, for example, Bridgeford, 1066, The Hidden History of the Bayeux Tapestry. or Clermont-Ferrand, p. 6.

- ^ Bridgeford, p. 181.

- ^ Bridgeford, p. 182.

- ^ Bridgeford, p. 186.

- ^ Bridgeford, p. 189 and p. 190.

- ↑ a b c Hicks, p. 27.

- ↑ a b Hicks, p. 31.

- ↑ Hicks, p. 30.

- ↑ Hicks, p. 32.

- ↑ Crafton, p. 17.

- ↑ Hicks, p. 39.

- ^ Bridgeford, p. 26.

- ^ Bridgeford, p. 27.

- ↑ a b Rud, p. 14.

- ↑ Crafton, p. 9.

- ^ Bridgeford, p. 29 and p. 30.

- ↑ a b Rud, p. 15.

- ^ Bridgeford, p. 33.

- ^ Bridgeford, p. 35.

- ↑ a b Wilson, p. 13.

- ^ Charles Alfred Stothard, The tapestry of Bayeux. London, Society of Antiquaries. Vestusta Monumenta Volume 6 with 17 facsimile engravings.

- ↑ Rud, p. 15 and p. 16.

- ^ Bridgeford, pp. 37 and 38.

- ↑ Crafton, p. 11.

- ^ Bridgeford, p. 39.

- ^ Bridgeford, p. 40.

- ^ According to the information provided by David Wilson, the research group was headed by an unspecified Count Metternich. See Wilson, p. 13.

- ^ Bridgeford, p. 43.

- ^ Bridgeford, p. 46.

- ↑ Rud, p. 16.

- ↑ Crafton, p. 12.

- ↑ Report from the newspaper Sueddeutsche from January 25, 2018: A carpet to reconcile France and Great Britain (accessed: January 25, 2018)