Sinzig

| coat of arms | Germany map | |

|---|---|---|

|

Coordinates: 50 ° 33 ' N , 7 ° 15' E |

|

| Basic data | ||

| State : | Rhineland-Palatinate | |

| County : | Ahrweiler | |

| Height : | 80 m above sea level NHN | |

| Area : | 41.03 km 2 | |

| Residents: | 17,630 (Dec. 31, 2019) | |

| Population density : | 430 inhabitants per km 2 | |

| Postal code : | 53489 | |

| Area code : | 02642 | |

| License plate : | AW | |

| Community key : | 07 1 31 077 | |

City administration address : |

Kirchplatz 5 53489 Sinzig |

|

| Website : | ||

| Mayor : | Andreas Geron (independent) | |

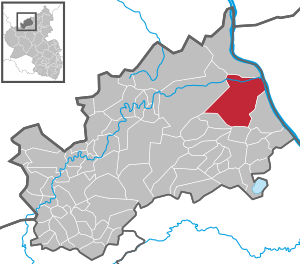

| Location of the city of Sinzig in the Ahrweiler district | ||

Sinzig is an association-free city on the Middle Rhine in the Ahrweiler district in Rhineland-Palatinate . According to state planning, the city is designated as a middle center. Sinzig is one of five German cities that are nicknamed Barbarossastadt .

geography

Sinzig is located in the lower Ahr valley on the left bank of the Lower Middle Rhine region two kilometers west of the river in the north of Rhineland-Palatinate , about ten kilometers from the North Rhine-Westphalian border . The closest major cities are Bonn (approx. 20 kilometers northwest) and Koblenz (approx. 30 kilometers southeast). The city is bordered to the east by the Rhine, otherwise it is surrounded by mountains that belong to the Eastern Eifel . To the west of the city center rises the Hellenberg ( 143 m above sea level ), south of the Wadenberg ( 138.7 m above sea level ).

The highest point in the urban area is 346 m above sea level. NHN on the edge of the Eifel in the Löhndorf district . The Ahr flows through Sinzig and flows into the Rhine. In Sinzig, Hellenbach and Harbach flow into the Ahr. The Frankenbach rises in the Sinziger Stadtwald .

City structure

Sinzig is divided into six local districts and 16 other municipal parts.

| District | Residents |

|---|---|

| Sinzig | 9,514 |

| Bad Bodendorf | 3,829 |

| Francs | 470 |

| Koisdorf | 845 |

| Löhndorf | 1,330 |

| Westum | 1,686 |

As of December 31, 2013

history

Etymology of the place name

The first mention of the place name as "Sentiacum" is proven in 762. According to the not undisputed name etymology of Dr. Hans Bahlow (1900–1982) the name Sinzig could be of Celtic origin and mean "constantly seeping water in the swampy forest", analogous to a district designation in the Rhön area ( Sinzigburg ). However, the actual geographic conditions speak against this etymology of the place name. Otto Kleemann gives in his "Pre and Early History of the Sinzig Area" as the origin of the name without being able to justify this assumption that the old name of Sinzig, Sentiacum, is based on the gentile name of a court founder and owner "around the turn of the ages" . Karl Bruchhäuser states in the "Heimatbuch der Stadt Sinzig" (Sinzig 1953) that the Roman consul and governor Gnaeus Sentius Saturninus († probably 66) could have given the place its name. What seems beyond doubt is that the suffix “-acum” in Sentiacum indicates a Celtic etymology of the place name. According to research by Dieter Schewes, the name Sinzig is more likely to be traced back to the Thracian auxiliary troops of the Romans based here, especially to the Thracian tribe of Sintoi.

Roman time

The roughly known history of Sinzig does not begin until two centuries later, when the Romans under the leadership of Gaius Iulius Caesar conquered the areas of Germania up to the Rhine. North of Sinzig, in Remagen , there had been a troop camp since the middle of the 1st century. For Sinzig, a loose settlement with rural homesteads can be assumed during this time and in the centuries to come. A Roman military brick factory was operated on the banks of the Rhine between 40 and 70 AD. Bricks from this brick factory were found on Sinziger Kirchberg. The floor of a Roman villa under Zehnthofstrasse was damaged in the course of the laying of gas pipes in the 1980s. From Trier around 160/170 the production of pottery (terra sigillata pots) was resumed in the Sinzig area near the Rhine . The new factory only existed for two decades. They exported goods by ship to Worms and Britain. In 1912, the remains of the pottery factory were uncovered: the work room, the kilns and waste pits.

The Roman settlement was probably not near the Rhine, but on the Sinziger church hill. This protrudes like a spur into the so-called Golden Mile, the area where the Ahr flows into the Rhine. At that time, unlike today, the mouth of the Ahr was a ramified system of small tributaries. The entire Ahr estuary up to what is now the Bad Bodendorf district was swampy. It has been proven that a Roman road led across the Golden Mile and connected the Confluentes military base (Koblenz) with the north.

Legend has it that a cross appeared in the sky on the Sinziger Helenenberg in the 4th century to promise her son, the Emperor Constantine, victory over his enemies. To what extent the Sinziger area was populated after the collapse of the Roman Empire is unknown.

middle Ages

The first documentary mention of Sinzig took place on July 10, 762 in a certificate of confirmation from the Frankish King Pippin the Younger . Pippin stayed in the sentiaco palatio , the royal estate of Sinzig. The donation of ownership and usage rights within the Sinzig district to the Reichskloster Prüm is noted in the deed . The Franconian royal court and thus the royal palace was at the intersection of the Frankfurt-Aachener Heerstraße. The Palatinate was of particular importance because it was a regular stopover on the coronation journey of the German rulers elected in Frankfurt to Aachen.

Einhard, the chronicler of Charlemagne , told in 814 about a "wine miracle" that is said to have taken place in the royal palace of Sinzig. In 855 the Carolingian Emperor Lothar I donated the St. Peter's Palatine Chapel with the associated rights of use and tithe to the Aachen Marienstift . In 1065 Heinrich IV gave the imperial city to his close adviser, Archbishop Adalbert von Bremen . In 1114 Sinzig was destroyed in the war between the German Emperor Heinrich V and the Archbishop of Cologne Friedrich I. von Schwarzenburg .

In its heyday from the 12th to 14th centuries, Sinzig was the seat of an imperial palace with numerous stays by German kings and emperors. Friedrich I. Barbarossa stayed in the Palatinate in 1152, 1158 and 1174, which is why the city is also called Barbarossa City . In 1255 - during the troubled times after the death of Emperor Friedrich II - Sinzig became a member of the Rhenish City Association , an association of numerous cities and some territorial lords that was part of the medieval peace movement Treuga Dei . According to Caesarius von Heisterbach, around 1200 a heretic Johannes and his mother were burned in Sinzig.

At the latest around 1267 Sinzig received city rights . In the first half of the 13th century the parish church of St. Peter was built in the late Romanesque style of the late Staufer period (consecrated in 1241). The consecrator of the church and the altar was the Dominican and Bishop Henricus de Osiliensis (Heinrich von Ösel), who during a stay in the Middle Rhine area (further consecration activities in August 1241 are documented for Koblenz and Boppard ) at the request and on behalf of the seriously ill Archbishop of Trier Theodorich (Dietrich) von Wied († 1242) made ordinations at various churches between Sinzig and Boppard. Due to the consecration on the day of the Assumption of the Virgin (first documented in 1310), the consecration of the largely completed parish church of St. Peter is assumed to be August 15, 1241. A hospital was also built. Many noble families were resident in Sinzig, which for this reason was called a cradle of the Rhenish nobility . Nine monasteries had properties in Sinzig.

According to a tax register from 1242, the Jewish community of Sinzig paid around a third of the city's tax revenue. For May 1, 1265, the Nuremberg memorandum reports that 71 people were burned in the Sinzig synagogue, including the prayer leader of the Cologne Jewish community. In 1287 another 46 Jews suffered martyrdom in Sinzig. After the plague epidemic of 1348/49, the remaining small Jewish community with twelve people was wiped out.

After 1297, with the construction of the city fortifications, city walls, wall, three city gates Ausdorfer Tor ( Oisdorpporzen 1350; Osterportz 1623), Leetor ( Leenporzen ) and Mühlenbachtor (since 1583 as Mühlenbacher Porzen , previously since 1350 Fischporzen ) and the two Wichhäuser (guard houses; documented as completed in documents of 1327, 1350 and 1353). Previously, on December 3, 1297 , King Adolf von Nassau allowed the citizens of Sinzig to levy a so-called Ungelds (tax) on the sale of wine and agricultural products, which was used exclusively to finance and build the city wall. In 1395/98 Jews were mentioned again in the city. The Judengasse was mentioned for the first time in 1433 .

The English King Edward III. was on a diplomatic and military mission on the Middle Rhine in the summer of 1338. Above all, it was about winning the French royal crown. On September 5, he took part in a solemn imperial assembly in Koblenz. On his outward journey from Antwerp to Koblenz, he also visited the imperial city of Sinzig. As early as the late 13th century, the gradual economic decline was marked by multiple pledging of the imperial property. With the final transfer of the imperial estate Sinzig into the possession of the Dukes of Jülich on January 19, 1348 (documentary confirmation of attachment by Charles IV to Margrave Wilhelm V von Jülich ), Sinzig again and finally came into a territorial marginal position. On June 30, 1421, Duke Adolf VII von Jülich-Berg sold half of Sinzig and its accessories for 15,000 guilders to Archbishop Otto of Trier . On August 24, 1425, Duke Adolf VII von Jülich-Berg also pledged the other half of Sinzig for 15,000 guilders to Archbishop Dietrich of Cologne . Kurköln and Kurtrier now each owned half of Sinzig and Remagen as pledge. On December 10, 1426, the archbishops Dietrich and Adolf concluded a truce to regulate the common administration. On March 14, 1451, Duke Gerhard von Jülich-Berg appointed the knight Lutter Quad , Lord of Tomburg and Landskron and Cologne Council, as bailiff of Sinzig and Remagen.

Modern times

Around 1794 Sinzig belonged to the Duchy of Jülich as part of the Sinzig-Remagen office . The lease and ownership changed several times. At times the city was divided between several owners. Duke Adolf VII von Jülich-Berg (1423–1437) and Duke Gerhard von Jülich-Berg (1437–1575) pledged the office to the Archbishops of Cologne. On Whit Monday 1583, careless shooting of the rifles at the Sinziger Mühlenbachtor led to a fire disaster in which the whole town of Sinzig burned down with its houses and yards, sheds and stables. In 1620, during the Thirty Years' War, Spanish troops under Spinola occupied Sinzig. In 1632, Sinzig was captured and sacked by Swedish troops under General Baudissin . In 1645 Sinzig opened its gates to the imperial general Peter Melander von Holzappel . On May 30, 1648, the Order of the Minorites laid the foundation stone for a monastery on the Helenenberg. In 1655 a Latin school was added. In 1688, French troops blew up the former ducal palace.

When a crypt was re-occupied, a mummified corpse was found in St. Peter's Church, which was identified as Vogt Wilhelm Holbach, time of death around 1670. A local cult developed around the undestroyed corpse, which was kidnapped to France during the French Revolution and returned to Sinzig in a triumphal procession after the victory over Napoleon. You can see them in the Church of St. Peter.

In 1758 another major fire struck the city. In 1767 Sinzig had 200 houses and around 850 residents. In 1782 there were five Jewish families with 23 people (1808/17 27, 1858 73 1895 75 1925 39 Jewish residents). It was not until the 19th century that the city experienced an economic revival through industrialization and the connection to the Cologne – Koblenz – Bingen railway line on the left bank of the Rhine (1858). From then on, the record factory was one of the city's main employers. The Sinzig synagogue was inaugurated in 1867. In 1933 there were still 41 Jewish residents living in Sinzig. After the November pogrom in 1938 there were 19 Jews in Sinzig and Bodendorf. The last of them were deported in 1942.

After the Federal Republic of Germany was founded in Bonn in 1949 , the first Federal Council Minister Heinrich Hellwege stayed in Sinzig for a short time and used the "Villa Sonntag" (Kölner Strasse 22) located here as his official residence. Due to billing problems in connection with the furnishing of the building, Hellwege moved out again, whereupon the Italian embassy settled in the villa. It then served as the temporary residence of the Ambassador of Uruguay in 1951/52 , then in 1954/55 as the chancellery of the Embassy of El Salvador . Today the building is used by the "Rheinische Provinzial-Basalt- u. Lavawerke GmbH & Co. oHG ”.

In 1972 the planned construction of a nuclear power plant in the greater Koblenz area became known, and the Golden Mile between Bad Breisig and Sinzig was named as one of the possible locations . For reasons of drinking water protection, however, this plan had to be abandoned later, and the Mülheim-Kärlich nuclear power plant was implemented instead .

Population development

The development of the population of Sinzig in relation to today's urban area; the values from 1871 to 1987 are based on censuses:

|

|

Incorporations

In the course of the territorial reform on June 7, 1969, the previously independent communities Bodendorf (then 1668 inhabitants), Franconia (373), Koisdorf (365), Löhndorf (939) and Westum (1060) were incorporated into the town of Sinzig.

History of the Sinziger Castle

In 1337 Emperor Ludwig the Bavarian allowed Margrave Wilhelm I of Jülich to build a castle. In 1348 a moated castle with four corner towers was built, which was expanded from 1569. In 1646 a further expansion served to improve the defensive systems. In 1689 the castle was set on fire by French troops.

In 1806 the castle property passed from state property to the possession of J. Peter Broicher and Franz-Joseph Hertgen. In 1850 Gustav Bunge and his wife Adele Bunge, b. Andreae, the castle property.

Today's Sinzig Castle was built in 1854/56 by the architect Vincenz Statz . The palace park was built between 1858 and 1866 according to plans by Peter Joseph Lenné . The wall paintings in the castle were made by Carl Andreae in 1863–1865. Gustav Bunge died in 1891, Adele Bunge in 1899.

The gardener's house on the south-west corner of the castle and other facilities were destroyed in air raids in 1944. In 1952, Kurbad GmbH acquired the castle and converted it. In 1954 the city of Sinzig bought the palace and park for DM 140,000 . In 1956 the local history museum, founded three years earlier, and the city archive moved to the first and second floors. The ground floor housed the cultural room and the registry office as well as the council hall until 1989. In 1988 the palace and park were placed under monument protection.

The earthquake in Roermond in April 1992 caused severe damage, which resulted in extensive renovation work.

politics

City council

The city council of Sinzig consists of 32 honorary council members, who were elected in a personalized proportional representation in the local elections on May 26, 2019 , and the full-time mayor as chairman.

The distribution of seats in the city council:

| choice | SPD | CDU | FDP | GREEN | FWG | total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2019 | 4th | 9 | 2 | 8th | 9 | 32 seats |

| 2014 | 6th | 12 | 2 | 4th | 8th | 32 seats |

| 2009 | 6th | 13 | 2 | 4th | 7th | 32 seats |

| 2004 | 6th | 15th | 2 | 4th | 5 | 32 seats |

* FWG = Free Voting Group “Bürgerliste Sinzig e. V. "

mayor

The mayors of the city since 1816:

|

|

Andreas Geron took office on January 1, 2018. In the runoff election on October 8, 2017, he was elected mayor for eight years with 71.5% of the vote, after none of the original three applicants had achieved a sufficient majority in the direct election on September 24, 2017.

coat of arms

| Blazon : "In gold over a tinned brick city wall growing out of the base of the shield, sloping upwards on both sides with a central tinned red pointed arched gate, a silver opening, a slightly raised three-pole black portcullis and a lowered drawbridge, a red-armored and braced black eagle with spread fangs. " | |

Town twinning

The town of Sinzig has had a partnership with the French town of Hettange-Grande in the Moselle department since June 1966 . A regular partnership-based exchange takes place between the two cities on a political, cultural and social level.

Culture and sights

Attractions

- A chapel at the location of today's parish church St. Peter in Sinzig was mentioned as early as 855. The current building dates from around 1225 to 1241. It was restored in 1863/64 according to plans by the architect Ernst Friedrich Zwirner . Among other things, the high altar from 1480 is worth seeing.

- Some remains of the medieval city fortifications, the construction of which began in 1297.

- The town hall was built on Kirchplatz from 1835 to 1837 by Johann Heinrich Hartmann as a town and school building. From 1879 to 1915 it served as a district court.

- The war memorial from 1914 to 1918 on a landing to the Church of St. Peter was created according to plans by the Cologne architect Franz Brantzky and the sculptor Willy Meller . The stone lion erected on a pedestal in front symbolizes the emotional state of the monument donors after the end of the First World War .

- Sinzig Castle by Vincenz Statz (1854–1858) with the town's local history museum. The builder of the castle was the Cologne merchant Gustav Bunge , who had the castle built as a summer residence for his family. The daughter Elisabeth Johanna Adele von Wedderkop (1851–1934), who married the Cologne bank director Ernst Friedrich Wilhelm Koenigs in 1872 , inherited the castle after her parents' death. After the war, the city acquired the castle and set up the local museum here.

- The monument to Emperor Friedrich I Barbarossa was erected on the occasion of the silver wedding of the married couple Gustav and Adele Bunge in 1875 in the roundabout of the palace gardens; since 1951 it has been in the park on Barbarossastraße below Sankt Peter.

- Zehnthof (presumably on the site of the old imperial palace)

- Nature reserve estuary of the Ahr

- Sinziger linden tree

- Ahrenthal Castle

- Feltenturm (11.25 m high observation tower with a view of the four valleys (Rheintal, Ahrtal, Hellenbachtal and Harbachtal))

Regular events

Culturally, Sinzig became known nationwide through the organization of the Sinziger Organ Week in the parish of St. Peter from 1976 to 1985. The initiative came from the avant-garde composer and organist Peter Bares at the time .

From 1993 to 2007 the Perry-Rhodan-Tage Rheinland-Pfalz took place in Sinzig, a nationally recognized literary event that dealt with the magazine novel series Perry Rhodan . In 2007 the event was under the patronage of the then Minister-President of Rhineland-Palatinate, Kurt Beck.

The “Barbarossamarkt zu Sinzig”, which has been held annually in the Sinzig Castle Park since 2004, is known for its authentic ambience. In addition to contemporary food, drinks and other goods, visitors to this medieval market are also offered a rich entertainment program with exhibition fights, jugglers and music and dance performances.

As part of its tower talks in the castle, the Association for the Promotion of Monument Preservation and the Local History Museum organizes regular lectures on historical and geographical topics. These often go beyond the framework of the city history of Sinzig!

Economy and Infrastructure

traffic

The Sinzig (Rhein) train station is on the Left Rhine route . It consists of 3 tracks on a house platform and a central platform. The Rhein-Express (RE 5) to Wesel and Koblenz and the Mittelrheinbahn (RB 26), which ends in Cologne or Mainz , stop here every hour . Trains in the direction of Koblenz and Mainz usually stop at track 1, the house platform, and in the direction of Cologne and Bonn at track 2. Track 3 is an overtaking and sideline.

schools

- Regenbogenschule Sinzig (primary school)

- St. Sebastianus Primary School Bad Bodendorf

- Hellenbachschule Westum (primary school)

- Barbarossaschule Sinzig ( secondary school plus )

- Rhein-Gymnasium Sinzig

- Janusz Korczak School Sinzig (special school)

Kindergartens (selection)

- Municipal kindergarten 'Max & Moritz' Bad Bodendorf

- Municipal kindergarten 'Zwergentreff' Franconia

- Catholic Kindergarten 'St. Georg ' Löhndorf

- Catholic Kindergarten 'St. Peter 'Sinzig

- Municipal kindergarten 'Storchennest' Sinzig

- Municipal day care center 'Spatzennest' Sinzig

- Municipal kindergarten Westum

youth club

- The HOT, House of the Open Door , Sinzig is available as a meeting point for young people .

Personalities

Born in Sinzig

- Franz Wilhelm Caspar von Hillesheim (1673–1748), President of the Electorate of the Palatinate and Minister

- Johann Classen-Kappelmann (1816–1879), entrepreneur and politician

- Norbert Kloten (1926–2006), economist

- Karl Deres (1930–2007), politician, 1980–1994 member of the Bundestag

- Thomas Maximilian Jansen (* 1939), political scientist and politician

- Inge Helten (* 1950), track and field athlete

- Günter Ruch (1956–2010), writer

- Franz XA Zipperer (1952–2015), music journalist and photographer

- Maximilian "Max" Strohe (* 1982), cook and restaurateur

Connected with Sinzig

- Ferdinand Jakob Nebel (1782–1860), architect, designed the parish church of St. Georg in Löhndorf , built from 1829 to 1833, and the parish church of St. Peter in Westum , built from 1843 to 1848

- Peter Joseph Lenné (1789–1866), garden artist and landscape architect, designed the palace gardens from 1858–1866 and the Zehnthof in 1864

- Karl Christian Andreae (1823–1904), painter, spent the last years of his life in Sinzig

- Peter Bares (1936–2014), organist, composer of church music, 1960–1985 church musician in Sinzig

- Rudi Altig (1937-2016), professional cyclist, a. a. 1962 winner of the Vuelta a España and winner of the green jersey of the Tour de France , 1966 road world champion at the Nürburgring . Lived in Sinzig- Koisdorf

- Titus Reinarz (* 1948), sculptor, lives and works in Sinzig

- Edgar Steinborn (* 1957), mechanical engineer, lives in Sinzig, and from 1987 to 2004 directed a total of 201 Bundesliga soccer matches

- Eveline Lemke (* 1964), politician (Greens), Member of the Bundestag , former minister D.

- Klaus Badelt (* 1967), German composer for television and film music, lived in Bad Bodendorf (Sinzig) during his childhood and youth

literature

- Ulrich Helbach : Palatinate town - imperial town - country town - small town - middle center. On the history of the city of Sinzig . In: Heimatjahrbuch Kreis Ahrweiler . Born in 1995, p. 59 ( online [accessed June 1, 2017]).

- Karl Bruchhäuser: Home book of the city of Sinzig. Sinzig 1953.

- Jürgen Haffke: Sinzig and its districts - yesterday and today . Ed .: Bernhard Koll. Sinzig 1983 (with numerous further references.).

- Hans-Jürgen Geiermann: Family book of the city of Sinzig with Westum and Koisdorf as well as individual farms and mills . West German Society for Family Research , Cologne 2002, ISBN 3-933364-58-2 .

- Dieter Schewe: History of Sinzig and its royal palaces - pivotal points of the Romans, Carolingians, Staufer between Upper and Lower Rhine 40 to 1227 . Sinzig 2004, ISBN 3-9809438-0-1 (With almost 1000 references and extensive bibliography.).

- Gottfried Kinkel : The Ahr . JP Bachem, Cologne 1999, p. 185 ff ., urn : nbn: de: 0128-1-2187 (Revised edition of the first edition from 1849.).

- Johannes H. Schroeder : Natural stone in Sinzig (Rhine). Use in architecture and city history . TU Berlin , Berlin 2017 ( link to download )

- Christian von Stramburg , Anton Joseph Weidenbach : Memorable and useful Rhenish Antiquarius ... . Dept. 3, Volume 9, Koblenz 1862 , p. 60.

- Memory of Sinzig on the Rhine . 1910, urn : nbn: de: 0128-1-3991 .

- Friedrich Strahl: Sinzig near Remagen on the Rhine. Mineral, spruce needle and gas bath, whey and grape curort . Neuwied 1857 ( online [accessed June 1, 2017]).

- Chronicle of the city of Sinzig . In: Gottfried Eckertz (Ed.): Fontes adhuc inediti rerum Rhenanarum. Lower Rhine Chronicles . Cologne 1864, p. 237 ff . ( Google Book in Google Book Search [accessed January 28, 2018]).

- Sinzig in the Topographia Westphaliae ( Matthäus Merian )

- The "holy" Vogt of Sinzig . In: The Gazebo . Issue 15, 1881, pp. 247–250 ( full text [ Wikisource ]).

Web links

- Sinzig website

- View of the Mühlenbach gate

- detailed description of the Jewish community of Sinzig. Alemannia Judaica

- Museum in Sinzig Castle

- Historical information about Sinzig at regionalgeschichte.net

- Literature about Sinzig in the Rhineland-Palatinate State Bibliography

Individual evidence

- ↑ State Statistical Office of Rhineland-Palatinate - population status 2019, districts, communities, association communities ( help on this ).

- ↑ a b State Statistical Office Rhineland-Palatinate - regional data

- ↑ Map service of the landscape information system of the Rhineland-Palatinate nature conservation administration (LANIS map) ( notes )

- ↑ Main statutes of the city of Sinzig. (PDF) § 4. June 27, 2019, accessed on July 24, 2020 .

- ↑ State Statistical Office Rhineland-Palatinate (ed.): Official directory of the municipalities and parts of the municipality. Status: January 2019 [ Version 2020 is available. ] . S. 4 (PDF; 3 MB).

- ^ Residents in the districts of Sinzig ( Memento from February 4, 2012 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Jürgen Haffke, Bernhard Koll (Ed.): Sinzig and its districts - yesterday and today . Sinzig 1983

- ↑ Schewe, History of Sinzig and his royal palaces

- ^ Friedrich Wilhelm Oediger (ed.), History of the Archdiocese of Cologne . Volume 1: The Diocese of Cologne from the beginning to the end of the 12th century . 2nd Edition. Bachem, Cologne 1971, p. 313

- ↑ William Knippler: Two cities - two developments. Sinzig 700 years of the city , in: Heimatjahrbuch Kreis Ahrweiler 1968, p. 66

- ↑ Germania Judaica I, pp. 325-326; II.2, pp. 766-768; III.2, pp. 1372-1374.

- ↑ Elsbeth Andre: 1338: The English King in Koblenz . Rhenish history portal (as of October 2, 2010)

- ↑ Rheinischer Antiquarius , III. Abt., Volume 9, p. 84

- ↑ Detailed explanation in Kinkel, Die Ahr , p. 189 ff.

- ↑ Stephan Pauly: The strangest saint in the Rhineland ( Memento from April 19, 2009 in the Internet Archive ) . New research results on the so-called "Holy Vogt" by Sinzig.

- ↑ Paul Wiertz: The "holy Vogt" of Sinzig . Summary of a contract before the Working Group for Regional History and Folklore in the Koblenz District (Working Group for Folklore) on September 29, 1966 in Sinzig. In: Landeskundliche Vierteljahrsblätter , 12, 1966, p. 168 f.

- ↑ Hans Kleinpass: The inauguration of the Sinzig synagogue in 1867 . In: HJbK Ahrweiler 1990 , p. 71.

- ^ Helmut Vogt : Rhineland-Palatinate, neighbor of the young federal capital. In: Bonner Geschichtsblätter , Volume 49/50, 1999/2000 (2001), ISSN 0068-0052 , p. 500; City of Bonn, City Archives (ed.); Helmut Vogt: "The Minister lives in a company car on platform 4": The beginnings of the federal government in Bonn 1949/50 , Bonn 1999, ISBN 3-922832-21-0 , p. 224.

- ↑ Diplomatic and other official foreign missions as well as representations of international organizations in the Federal Republic of Germany (as of September 1954). In: Bulletin of the Press and Information Office of the Federal Government , Deutscher Bundes-Verlag, 1954, p. 1554 ff.

- ↑ Günther Schmitt: industrial area Goldene Meile - the near nuclear power plant. In: Genearl-Anzeiger (Bonn). October 24, 2013, accessed February 20, 2018 .

- ↑ Official municipality directory 2006 ( Memento from December 22, 2017 in the Internet Archive ) (= State Statistical Office Rhineland-Palatinate [Hrsg.]: Statistical volumes . Volume 393 ). Bad Ems March 2006, p. 196 (PDF; 2.6 MB). Info: An up-to-date directory ( 2016 ) is available, but in the section "Territorial changes - Territorial administrative reform" it does not give any population figures.

- ^ The Regional Returning Officer RLP: City Council Election 2019 Sinzig. Retrieved August 11, 2019 .

- ^ Anton Keuser: The mayors of Sinzig in Prussian times , home yearbook of the Ahrweiler district 1961 and various other home yearbooks

- ↑ Victor Francke: Andreas Geron wins mayoral election in Sinzig. General-Anzeiger Bonn, October 8, 2017, accessed on December 17, 2019 .

- ^ Rhein-Zeitung - The Feltenturm on the Mühlenberg, accessed on February 19, 2013

- ^ Website for the Perry Rhodan-Tage Sinzig

- ^ Barbarossamarkt zu Sinzig ( Memento from September 11, 2015 in the Internet Archive )

- ^ Sinzig train station on bahnhof.de

- ↑ Sinzig Open House. Catholic parish of St. Peter, accessed February 20, 2018 .