Bad Neuenahr-Ahrweiler

| coat of arms | Germany map | |

|---|---|---|

|

Coordinates: 50 ° 33 ' N , 7 ° 7' E |

|

| Basic data | ||

| State : | Rhineland-Palatinate | |

| County : | Ahrweiler | |

| Height : | 99 m above sea level NHN | |

| Area : | 63.4 km 2 | |

| Residents: | 28,468 (Dec. 31, 2019) | |

| Population density : | 449 inhabitants per km 2 | |

| Postal code : | 53474 | |

| Primaries : | 02641, 02646 | |

| License plate : | AW | |

| Community key : | 07 1 31 007 | |

| City structure: | 10 districts , 13 city districts |

|

City administration address : |

Hauptstrasse 116 53474 Bad Neuenahr-Ahrweiler |

|

| Website : | ||

| Mayor : | Guido Orthen ( CDU ) | |

| Location of the city of Bad Neuenahr-Ahrweiler in the Ahrweiler district | ||

Bad Neuenahr-Ahrweiler is an association-free city and seat of the district administration of the Ahrweiler district in northern Rhineland-Palatinate . Bad Neuenahr-Ahrweiler is a state-approved spa and designated as a medium-sized center according to state planning .

The city was created in 1969 through the merger of the two neighboring cities of Ahrweiler and Bad Neuenahr and the four communities of Gimmigen , Heimersheim , Kirchdaun and Lohrsdorf of the Bad Neuenahr community . In 1974, what was then the local community of Ramersbach was incorporated as the southernmost district.

In 2022 Bad Neuenahr-Ahrweiler will host the fifth Rhineland-Palatinate state horticultural show .

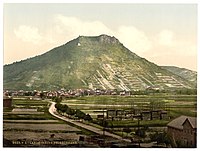

geography

Bad Neuenahr-Ahrweiler is located in the Ahr valley on the left bank of the Rhine , in the north of Rhineland-Palatinate, about ten kilometers from the state border with North Rhine-Westphalia . The closest major cities (at least 100,000 inhabitants) are the federal city of Bonn (straight line: 21 kilometers), Koblenz (40 kilometers) and Cologne (45 kilometers). The city is surrounded by mountains that belong to the Ahr Mountains and on the southern slopes of which wine is grown.

The highest mountain in the urban area is the little house at 506 m above sea level. NHN . Further surveys are the Steckenberg south to ( 371 meters ) and the Neuenahrer Mountain ( 339 m ) and the east the Talerweiterung final Landskrone ( 272 m ). Castles once stood on the latter two mountains .

Neighboring communities

The city of Bad Neuenahr-Ahrweiler borders on nine cities, municipalities and local communities .

| county | Remagen | |

| Dernau |

|

Sinzig |

|

Right Kesseling Heckenbach |

Schalkenbach | Koenigsfeld |

City structure

Bad Neuenahr-Ahrweiler is divided into local districts , which consist of one or more districts . The city has 10 districts with 13 districts. The local districts are represented by local councilors and local councils. The largest district, Bad Neuenahr, was formed in 1875 from three communities that are still understood as districts today.

population

There are 28,468 people living in the city of Bad Neuenahr-Ahrweiler (December 31, 2019). The inhabitants are spread over 14,940 apartments. With a statistical population density of 449.02 inhabitants per square kilometer, the city is relatively densely populated (Germany has a population density of 230 inhabitants per square kilometer). The proportion of the female population at 53.5 percent exceeds that of the male population at 46.5 percent. The largest age groups are those of the 50 to 64 year olds (21.9 percent) and the 65 to 79 year olds (21.5 percent). The old-age quotient (population aged 65 and over per 100 of the 20 to under 65-year-old population) exceeds the youth quotient (under 20-year-olds per 100 of the 20 to under 65-year-old population) at 60.9 percent. The population increased by 333 people (1.2 percent) in 2015 compared to the previous year. The proportion of foreigners (registered residents without German citizenship ) was 9.0 percent on December 31, 2015.

| District | Breakdown | population |

|---|---|---|

| Ahrweiler | District: Ahrweiler | 7,519 |

| Bachem | District: Bachem | 1,198 |

| Bad Neuenahr | Districts: Beul , Hemmessen and Wadenheim | 12,888 |

| Gimmies | District: Gimmigen | 748 |

| Heimersheim | Districts: Heimersheim and Ehlingen | 3,204 |

| Heppingen | District: Heppingen | 899 |

| Kirchdaun | District: Kirchdaun | 352 |

| Lohrsdorf | Districts: Lohrsdorf and Green | 730 |

| Ramersbach | District: Ramersbach | 588 |

| Walporzheim | Districts: Walporzheim and Marienthal | 705 |

Population development

The development of the population of Bad Neuenahr-Ahrweiler based on today's urban area; the values from 1871 to 1987 are based on censuses:

|

|

history

antiquity

Finds from the Hallstatt period (1000 to 500 BC) show that Celts were resident in the region and practiced agriculture and cattle breeding. In the years 58 BC Until 50 BC The Gallic War was waged, a consequence of which was the almost complete annihilation of the autochthonous Celtic indigenous people who belonged to the tribe of the Eburones. Germanic tribal associations moved into the areas on the left bank of the Middle Rhine. Numerous finds from Roman times exist from the 1st to 3rd centuries; including the Villa Rustica on the Silberberg .

middle Ages

In 893 Ahrweiler was first named in the Prümer Urbar (list of goods from the Benedictine Abbey of Prüm ) as Arwilre , Arewilre , Arewilere and later Arweiller . After that, the abbey in Ahrweiler owned a manor with 24 farmsteads, 50 acres of arable land and 76 acres of vineyards. The village of Wadenheim was first mentioned in 992, almost a hundred years later, Hemmessen followed in 1106. The first documentary mention of a parish church in Ahrweiler comes from the year 1204, around 1225 the Neuenahr Castle and the county of Neuenahr ( Newenare ) were acquired by the Counts of Are- Nürburg built, the family was named after the castle. Twenty years later, King Conrad IV had Ahrweiler pillaged by Burgrave Gerhard von Landskron. The village was donated to the Archdiocese of Cologne in 1246 .

On August 2, 1248 approval has been granted the city rights to citizens of Ahrweiler by Archbishop Konrad I of Are-Hochstaden in Are ( Altenahr ). In 1250 the construction of the still existing city wall of Ahrweiler began and was completed about ten years later. Around the year 1255, Ahrweiler was regularly called a city ( Latin oppidum = "city"), but it was not until 1320 that it received the city seal . In 1269 the construction of the St. Laurentius parish church began, which is one of the few churches still in use today with a " Judensau relief" (gargoyle). A document dated February 22, 1277 for the first time contains evidence of Ahrweiler as a municipality and names the representatives of the local self-government: lay judges, citizens and municipality of Ahrweiler (scabini, burgenses ac universitas in Arwilre).

By the 13th century at the latest, Jews were living in Ahrweiler under the protection of the Archbishop of Cologne. In the course of the plague pogroms of 1348/49, the Jewish community was wiped out; Jews have been in the city again since 1367/70. A mikveh can also be identified. Scribes are also mentioned among the Jewish inhabitants of the city.

In 1343 the dukes of Jülich received the county of Neuenahr as a fief . Around 1350, the inner city quarters of Oberhut, Adenbachhut, Niederhut and Ahrhut were first mentioned. In 1352, after the death of Count Wilhelm von Neuenahr, serious inheritance disputes followed, as his male line died out with him. Ahrweiler's oldest preserved town seal dates from 1365. In 1366 Ahrweiler joined the Maas-Rhein peace alliance , which was established on May 13, 1351 between Archbishop Wilhelm von Gennep , Duke Johann von Brabant, his son Duke Gottfried von Limburg (* 1347, † 1352) and the cities of Cologne and Aachen for ten years agreed and then steadily extended.

To an intervention by the Archbishop of Cologne Friedrich III. It came from Saar Werden in 1372, Neuenahr Castle was destroyed and Kurköln became a co-owner of the county. Two years later, the village of Beul in the county of Neuenahr was first mentioned. The Ahrweiler Huten (Ahrhut, Niederhut, Oberhut, Adenbachut), originally fiscal civil communities, were entrusted with military duties in 1411. The Prüm Abbey remained the landlord of Ahrweiler and received considerable interest on wine. The parish church was the abbey’s own church and in the 14th century was still served by a Prüm conventual as local priest. In 1373 there was a dispute about this, which went as far as the Curia in Rome and there it was decided in favor of the abbey and its candidate.

After the death of Archbishop and Elector Dietrich II of Moers on February 14, 1463, almost all of the palaces, castles, offices and pensions were in the hands of pledge holders. As a result, on March 26, 1463, the Rhenish Hereditary Land Association took place in Kurköln , which had to be sworn by the Archbishop. The Cologne cathedral chapter , the counts, knights and the most important cities participated in it. The city of Ahrweiler also sealed the union. In the course of the Cologne collegiate feud (1473-1480), Ahrweiler was besieged in April and May 1474 by troops of the Cologne Archbishop Ruprecht von der Pfalz . Walls and hats repelled the attacks.

Modern times

The oldest surviving town ordinance for Ahrweiler dates from 1510. 36 years later, in 1546, the county of Neuenahr was recaptured by the Duke of Jülich; since then the county was united with the duchy of Jülich as an office of Neuenahr. There were also witch hunts in Ahrweiler. A first, handed down memo indicates a corresponding execution in 1501: Do Tryne van Eich burned war , it says in the council note. Details are handed down in a detailed general account handed down for the years 1628/29, which, because of the witchcraft alhi, in addition to the special judicial accounts, faced the expense of every person . The executions then took place on Honenstein behind the Kalvarienberg . In 1629 the witch hunt reached its climax with the burning of the wife of the mayor Stapelberg. In the said accounts of the Ahrweiler witch trials, 26 people are named who were burned.

With the Treaty of Xanten from 1614 as a result of the Jülich-Klevische succession dispute, Neuenahr fell to the Duchy of Palatinate-Neuburg. Field Marshal Wolf Heinrich von Baudissin forced entry into the city in 1632, but there was no looting for a large sum on December 11th. Four years later, Bernhard von Sachsen-Weimar conquered Ahrweiler. After the defeat of the imperial troops in the battle of Krefeld (Lower Rhine) under General Guillaume de Lamboy on January 17, 1642, 2,200 men on foot and 700 cavalrymen were placed in Ahrweiler for four months; there was looting, pillage, robbery and rape. In July 1646, the French general Vicomte de Turenne conquered Ahrweiler. Again there was looting, robbery and murder. Just two years later, the plague claimed more lives than the Thirty Years' War before .

The mayor's office of Neuenahr and Jülich-Berg fell to the Electoral Palatinate in 1685 . During the Palatinate War of Succession , French troops occupied Ahrweiler on September 7, 1688. During their retreat under General Henri d'Escoubleau, comte de Montluc , the French set the city on fire on May 1, 1689; Ahrweiler was burned down to ten houses.

Until the end of the 18th century, today's urban area belonged to different territories :

- Ahrweiler was a bailiwick of the Electorate of Cologne to which Bachem , Marienthal and Walporzheim also belonged

- Bad Neuenahr ( Wadenheim with buckling and Hemmessen ) and Ramersbach belonged to the Duchy of Jülich ( Amt Neuenahr )

- Heimersheim , Heppingen and Ehlingen also belonged to the Duchy of Jülich ( Amt Sinzig-Remagen )

- Lohrsdorf with Green belonged to the Landskron rule

- Gimmigen and Kirchdaun were jointly owned by the dukes of Jülich and the lords of the Landskron; the Jülich part was under the Sinzig-Remagen office.

In 1794 the entire Left Bank of the Rhine was occupied by French revolutionary troops in the First Coalition War. From 1798 to 1814, today's urban area belonged to the Rhine-Moselle department ( French: Département de Rhin-et-Moselle ), Ahrweiler became the chief town ( chef-lieu ) of the canton of the same name , and the remaining current districts belonged to the canton of Remagen .

At the beginning of 1814, French rule ended in the areas on the left bank of the Rhine. The previous Rhine-Moselle department was provisionally assigned to the Generalgouvernement Mittelrhein . Due to the agreements made at the Congress of Vienna , the region came under the Kingdom of Prussia in 1815 . Under the Prussian administration today's urban area in 1816 came to the newly built district Ahrweiler in Koblenz , which is part of the Grand Duchy of the Lower Rhine and from 1822 to part of the Rhine province was. The present city area was administered by the mayor's office Ahrweiler , Ramersbach belonged to the mayor's office of Königsfeld . The city of Ahrweiler left the mayors' association in 1857 and formed its own urban administrative district.

The road tunnel near Altenahr was opened in 1834, and tourism began . About 20 years later - in 1852 - the Apollinaris fountain was drilled. In 1856 the healing springs were opened and two years later a spa was founded in Wadenheim.

In 1875 the places Wadenheim, Hemmessen and Beul were merged to form the community of Neuenahr (derived from the name of the former castle and county). The mayor's office in Ahrweiler-Land was renamed the Neuenahr mayor's office, and the seat of the mayor and the administration was relocated from Ahrweiler to Wadenheim. The Ahr Valley Railway from Remagen to Ahrweiler was opened in 1880 (in 1886 it led to Altenahr, in 1888 to Adenau and in 1910 the double-track expansion began). From 1906 to 1917, the Ahrweiler Electric Trackless Railway , an early trolleybus operator , also ran in the city . Between 1899 and 1901 the thermal bath house , the east building, the spa hotel and the spa house were built.

In 1908 the Ahrgau Museum was founded by Peter Joerres . The Ahr flood claimed several lives in 1910. Cardinal Archbishop Antonius Fischer died on July 30, 1912 while taking a cure . On July 5, 1927, the Prussian State Ministry approved the coat of arms of the Ahrweiler district. In the same year the medicinal properties of the springs were recognized - Neuenahr became Bad Neuenahr .

In 1933 there were 31 Jewish residents (ten families) in Ahrweiler and 96 Jewish residents in Bad Neuenahr. In the course of the November pogroms in 1938 , the synagogue in Ahrweiler and existing Jewish shops in what is now the city area were devastated. The synagogue in Bad Neuenahr was also devastated and then burned down. It was in Tempelstrasse , which on December 20, 1938, was renamed Wadenheimer Strasse at the request of the Thür local group leader . In 1942 the last Jewish residents were deported to extermination camps . Between 2012 and 2015, 72 stumbling blocks were laid in three parts of the city to commemorate them .

During the Second World War , severe war damage occurred in the last two years of the war due to Allied bombing raids on Ahrweiler, with 126 houses being destroyed, especially in the lower Ahrhutstrasse, Schützbahn and Blankenheimer Hof. In the nearby Silberberg tunnel , residents sought protection from the air raids. Today's urban area became part of the then newly formed state of Rhineland-Palatinate within the French occupation zone after the war . In 1951 Bad Neuenahr was promoted to town .

In 1953, the federal school of the Federal Agency for Technical Relief was established in the Marienthal district. In 1971 the THW federal school was converted into the federal disaster control school. A Roman villa was discovered in 1980 during construction work on Bundesstraße 267 . The Ahrthermen were built between 1991 and 1993. In 1995, the Bad Neuenahr compromise was reached : a historic agreement was reached between the German state governments on a new interstate broadcasting agreement . The European Academy Bad Neuenahr-Ahrweiler for researching the consequences of scientific and technical developments ( technology assessment ) was founded in 1996, the same year the Academy for Emergency Planning and Civil Protection (AkNZ) - since 2002 Academy for Crisis Management, Emergency Planning and Civil Protection (AKNZ) - was established .

Merger

Today's city of Bad Neuenahr-Ahrweiler was created in the form of a new formation on June 7, 1969 from the two cities of Ahrweiler and Bad Neuenahr and the communities of Gimmigen , Heimersheim , Kirchdaun and Lohrsdorf ( Verbandsgemeinde Bad Neuenahr ). The municipality of Ramersbach was incorporated on March 16, 1974.

religion

The predominant religion in Bad Neuenahr-Ahrweiler is Roman Catholic Christianity . Evangelical Christians are in the minority . According to the 2011 census, 59.7% of the 26,811 inhabitants belonged to the Roman Catholic Church, 18.5% to the Evangelical Church in Germany, 2.5% to others such as the Evangelical Free Church of Rhein-Ahr ( Baptists ) and 18, 6% do not belong to any religious society under public law .

The regional synod of the Evangelical Church in the Rhineland meets annually, mostly in January, in the Bad Neuenahr district.

politics

household

According to the 2019 budget of the city of Bad Neuenahr-Ahrweiler, the earnings budget provides for income (income) of EUR 57,925,765.00 and expenses (expenditure) of EUR 57,881,955.00 (annual net income for 2019: EUR 43,810.00) . The city's equity amounted to EUR 126,576,514.55 as of December 31, 2017.

City council

The city council in Bad Neuenahr-Ahrweiler consists of 36 honorary council members, who were elected in a personalized proportional representation in the local elections on May 26, 2019 , and the presiding mayor .

The distribution of seats in the City Council of Bad Neuenahr-Ahrweiler is as follows:

| choice | SPD | CDU | AfD | Green | FDP | left | FWG 1 | Flat share 2 | Total seats |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2019 | 5 | 15th | 1 | 7th | 2 | 1 | 4th | 1 | 36 |

| 2014 | 7th | 17th | - | 4th | 1 | 1 | 4th | 2 | 36 |

| 2009 | 6th | 17th | - | 4th | 3 | - | 5 | 1 | 36 |

| 2004 | 7th | 20th | - | 3 | 2 | - | 4th | - | 36 |

mayor

- 1969–1993: Rudolf Weltken (CDU)

- 1994–2002: Edmund Flohe (CDU)

- 2002–2010: Hans-Ulrich Tappe (CDU)

- since 2010: Guido Orthen (CDU)

The fully qualified lawyer Guido Orthen took office on August 1, 2010. In the direct election on November 12, 2017, he was confirmed in office for a further eight years with 84.4% of the votes.

National emblem

The city of Bad Neuenahr-Ahrweiler has a coat of arms and a flag as a national emblem .

| Blazon : "Shield split from red and gold, in the base of the shield covered with a crown in mixed up colors, in front a silver eagle, behind a black, red-tongued and armored lion" | |

| Reasons for the coat of arms: The coat of arms was approved on October 15, 1971 by the Koblenz district government . The eagle refers to the Counts of Are , who were sovereigns of Ahrweiler from 1100 to 1246. The lion stands for the rule of the dukes of Jülich (until 1614). The crown (German imperial crown) is a reference to the rule Landskron , to which the districts Heimersheim, Heppingen, Gimmigen, Kirchdaun and Lohrsdorf belonged. |

Description of the banner flag: "The banner is yellow-red striped lengthways with the coat of arms above the middle."

Town twinning

Bad Neuenahr-Ahrweiler has had a partnership with the Belgian municipality of Brasschaat in the Flanders region since 1988 .

Economy and Transport

economy

Bad Neuenahr-Ahrweiler is a health resort with carbonated soda thermal baths at the Apollinaris spring, significantly shaped by viticulture and, with 284 hectares of vines, the largest wine-growing community in the Ahr . Mainly red wine vines are planted.

Furthermore, industrial companies such as Apollinaris ( Coca-Cola ), ZF Sachs (formerly Boge) and JM Schmitt do their part to ensure the economic stability of the place. In addition, the Bundeswehr was one of the major employers until the end of 2012 with the Army Materials Office , later the Army Logistics Center , in the "Ahrtal Barracks" . The barracks site was bought by the Sprengnetter Group ( Immobilienvaluation GmbH) and is to be expanded as the company headquarters and the in-house academy.

The German Red Cross runs a specialist hospital for child and adolescent psychotherapy .

The Tourism is another important sector for the medium-sized town. In 2015, almost 237,000 guests were counted in around 200 accommodation establishments. Above all, Bad Neuenahr, as one of the few privately run spas in Germany, with its numerous large clinics and hotels stands for most jobs, optimally complemented by Ahrweiler with its medieval old town , it is a popular excursion and holiday destination for tourists. The restaurant Zur Alten Post by Hans Stefan Steinheuer in the Heppingen district is one of the ten best in Germany with two Michelin stars . The Bad Neuenahrer Ahr thermal baths with their world-famous springs are counted among the most beautiful thermal bathing landscapes in Europe.

Numerous spa and hiking trails offer routes of varying degrees of difficulty. For example the red wine hiking trail , the AhrSteig , the Ahr cycle path and various circular hiking trails.

In the urban area, a total of 19,210 employees are subject to social security contributions , of which 10,446 are at the place of work and 8,764 at the place of residence (June 30, 2015). Of the employees subject to social security contributions, 6,203 inbound and 4,523 outbound commuters.

traffic

air traffic

The Bad Neuenahr-Ahrweiler airfield is located directly north of the city and is approved as a special airfield . The paved runway is 500 meters long. The flight operation is approved for aircraft up to two tons maximum weight, helicopters , motor gliders , gliders , microlights and air sports equipment as well as balloons . The place is subject to a PPR regulation (prior permission required) and can be approached during visual flight - weather conditions.

Rail transport

The metropolitan area is the public transportation well developed (PT) through its five stations or stops . The Bad Neuenahr and Ahrweiler train stations as well as the Heimersheim , Ahrweiler Markt (close to the historic city center of Ahrweiler) and Walporzheim are on the Lower Ahr Valley Railway ( KBS 477 ) Remagen - Ahrbrück . Another train stop in Bad Neuenahr Mitte is also being planned. In the local rail passenger transport (SPNV) the "Rhein-Ahr-Bahn" (RB 30 ) connects Bonn main station with Ahrbrück every hour and the "Ahrtalbahn" (RB 39) Remagen with Dernau every hour.

Streets

Bad Neuenahr-Ahrweiler is connected to the trunk road network via the motorway slip roads 571 and 573 to the federal motorway 61 .

A railway called Ahrtal-Express runs between Bad Neuenahr and Ahrweiler .

From 1906 to 1917, the trolleybuses of the Ahrweiler Electric Trackless Railway connected the city center of Ahrweiler with the Walporzheim district and the Neuenahr districts of Hemmessen and Wadenheim.

Culture and sights

In the district of Ahrweiler is the Roman villa , in which a mansion from the Roman times of the 2nd to 3rd century is exposed and housed. The manor house, along with the large bathing wing , is very well preserved, which means that potential visitors can get a very vivid insight into the upscale Roman way of living. In Ahrweiler itself there are many splendid, lavishly restored half-timbered houses and a well-preserved medieval city wall with some of the moats still in place . All four city gates , Ober-, Walporzheimer or Gisemer Tor, Nieder- or Rheintor, Adenbach- or Winzertor and Ahrtor have been preserved. The gates are built very differently, two are double tower gates (Ahrtor, Niedertor), two three-walled gates (on the city side open, portalless gates). The upper gate was provided with a fourth wall on the open city side in 1500 and has had two portals since then . The Adenbachtor - named after the deserted town of Adenbach - was only restored in 1974 after 285 years. Of the three medieval residential towers, only the White Tower , which has had an often renewed Baroque hood instead of the Gothic helmet since the 17th century , and the Kolwenturm (Colventurm, often rebuilt) at the Adenbachtor (today Adenbach Castle Restaurant) have been preserved. The tavern tower near the Obertor (also Kautenturm, Runder Turm, Roter Turm) was demolished in 1811. Furthermore, two of the seven medieval noble courts, the (large) Blankartshof (formerly Fischenicher Hof) and the Deutsche Hof, as well as two monastery courtyards have been preserved: the Prümer Hof and the Rodderhof. The Adelshöfe Dalwigkscher Hof (in front of the Adenbachtor), Ehrensteiner Hof (next to the Prümer Hof), Gymnicher Hof (wine-growing area), Kolwehof (near Adenbachtor) and the Eltzer Hof (former (smaller) Blankartshof) at the Ahrtor no longer exist.

The district of Bad Neuenahr is a well-known spa town with associated notable spa facilities and facilities, such as the Ahr thermal baths and the Kurhaus (built 1903–1905), which now houses the casino . Numerous villas and spa hotels , including the former imperial post office , after which Poststrasse is named, still bear witness to the heyday of the spa at the end of the 19th and first half of the 20th century. Bad Neuenahr was originally formed from the towns of Beul, Wadenheim and Hemmessen. Individual building objects such as chapels, the renting works or half-timbered houses still bear witness to their history.

To the south of Neuenahr, remains of the eponymous castle of the Counts of Neuenahr (destroyed in 1372) can still be found on the Neuenahrer Berg. A 15-meter-high observation tower, popularly known as the “Langer Köbes”, was built in its place in 1972 . On the Steckenberg, south of Bad Neuenahr, there is another observation tower, the stone Steckenberg Tower, which was first built in 1914 and later in 1959.

The Willibrordus Church on the right side of the Ahr above the Rentei was the Wadenheimer parish church . It comes in parts from the late romantic period . The Rosary Basilica by the architect August Menken was built in Wadenheim from 1899 to 1901 ; its 60 meter high tower influences the cityscape. The chapel in Hemmessen ( St. Sebastian ) was built in 1869 in place of an earlier one.

In 2002, at an international sculpture symposium along the Ahr, the Bad Neuenahr-Ahrweiler sculpture trail was created . It is also part of the Rhineland-Palatinate Sculpture Trail .

Regular city tours take place during the main tourist season.

The now abandoned and largely dismantled alternative seat of the federal constitutional organs was located in the Marienthal district , which was intended to offer central federal organs a safe refuge in the event of a defense . A small part of this “government bunker” that has not been dismantled was opened in 2007 as the Cold War Museum . Also known is the ruins of the Augustinian nuns - monastery .

One of the most renowned restaurants in Germany is located in the Heppingen district. Hans Stefan Steinheuer's restaurant Zur Alten Post has been contributing to the region's culinary boom since 1986 when it received its first Michelin star .

In the district of Ramersbach there is an Art Nouveau church. St. Barbara was built in 1908 and celebrated its 100th anniversary in 2009. A chronicle was drawn up for this occasion in 2008.

On April 19, 2012, the Cologne artist Gunter Demnig laid the first 30 “ stumbling blocks ” in memory of the Jewish victims of National Socialism in Bad Neuenahr-Ahrweiler. In 2013, more stumbling blocks should be added in the city area.

Sports

The SC 07 Bad Neuenahr (officially Sportclub 07 Bad Neuenahr eV) was a German football club from Bad Neuenahr-Ahrweiler with the club colors red and black. The club's flagship was the women's football department founded in 1969 , which won the German championship in 1978. The SC 07 was a founding member of the women's Bundesliga and after several promotions and relegations from 1997 to 2013 belonged to this division without interruption. After filing for bankruptcy , SC 13 Bad Neuenahr was founded on September 28, 2013 as a pure women's football club, which succeeded SC 07 in January 2014.

In the Bad Neuenahr district there is a 14-court tennis facility on which the “National German Tennis Championships for Seniors” take place every year.

Training institutions

In the district Ahrweiler is on the rise Godeneltern founded in 1996 and renamed in 2002 Academy of crisis management, emergency planning and civil protection (AKNZ) of the Federal Office for civil protection and disaster relief (BBK) established that as the central training facility of the Federal in the field of civil protection functions.

education

There are twelve schools in Bad Neuenahr-Ahrweiler that are attended by around 5100 students. There are four grammar schools (around 2900 students in total): The Bad Neuenahr district is home to the Peter-Joerres grammar school , the Are grammar school , which is organized as an all-day school , and the private full-day school with boarding school Carpe Diem (G9GTS). The Calvarienberg monastery school , run by the Ursulines , is located in Ahrweiler and now gives co- educational lessons. There is also a secondary school (around 360 students) belonging to the Calvarienberg monastery school (girls' school), as well as two secondary schools plus (the Philipp-Freiherr-von-Boeselager secondary school and the Erich-Kästner secondary school plus ) with a total of around 930 students. There are also two special needs schools ( Don Bosco School and Levana School ) with a total of around 260 students, a vocational school (around 2,700 students) and the Carpe Diem private school with a boarding school .

The city has three primary schools with a total of around 700 students, one each in the districts of Ahrweiler, Bad Neuenahr and Heimersheim.

Personalities

Born in Bad Neuenahr-Ahrweiler

- Johannes Gamans (1606–1684), Jesuit and historian

- Georg Kreuzberg (1796–1873), discoverer of the source of the Apollinaris fountain

- Carl-Alexander von Ehrenwall (1855–1935), founded the Dr. von Ehrenwall'sche Kuranstalt for the mentally and mentally ill in Ahrweiler .

- Albert Kreuzberg (1871–1916), District Administrator of the Schleiden district

- Cyrillus Jarre (1878–1952), Franciscan Martyr Archbishop in Jinan / China

- Pitt Kreuzberg (1888–1966), painter

- Georg Kraft (1894–1944), prehistorian

- Carl Weisgerber (1891–1968), landscape and animal painter

- Stefan Leuer (1913–1979), church architect and university professor

- Peter Recker (1913–2003), glass and mosaic artist of religious motifs

- Konrad Schubach (1914–2006), District Administrator in Bitburg, President of the Trier District, State Secretary in the Rhineland-Palatinate Ministry of Agriculture

- Winfried Boeder (* 1937), philologist (Caucasian languages)

- Alfred Schüller (* 1937), economist

- Matthias Fell (* 1940), athlete, former President of the West German Volleyball Association

- Rolf Caesar (* 1944), German economist

- Ulrich Nonn (* 1942), historian

- Edgar Lersch (* 1945), archivist and media historian

- Ute Büchter-Römer (* 1946), professor of music education

- Gregor Lersch (* 1949), florist

- Wolfgang Schlagwein (* 1957), member of the state parliament (Alliance 90 / The Greens)

- Hans Stefan Steinheuer (* 1959), cook

- Wolfgang Gieler (* 1960), political scientist and university professor

- Horst Gies (* 1961), Member of the State Parliament (CDU)

- Jürgen Seul (* 1962), lecturer, editor and author (legal publication series on Karl May)

- Dieter Romann (* 1962), President of the Federal Police Headquarters since 2012

- Markus Stenz (* 1965), conductor

- Günther Grün , (* 1965), mathematician and university professor

- Benedikt Vallendar (* 1969), publicist

- Marc Kochzius (* 1970), marine biologist

- Rolf Kreyer (* 1973), English studies

- Marc Metzger (* 1973), comedian

- Björn Glasner (* 1973), racing cyclist

- Jan van Eijden (* 1976), track cyclist

- Pierre Kaffer (* 1976), racing car driver

- Bianca Rech (* 1981), soccer player

- Kilian Jakob (* 1998), soccer player

Connected with Bad Neuenahr-Ahrweiler

- Nikolaus Heyendal (1658–1733), theologian and abbot of Rolduc Abbey (had the collapsed Klosterrather Hof in Ahrweiler, today's first-class hotel Rodderhof , rebuilt in 1714 )

- Karl Marx (1818–1883) (1877 last stay in Germany as a spa guest in Bad Neuenahr in the "Hotel Flora")

- Peter Friedhofen (1819–1860), chimney sweep, founder of the Barmherzigen Brüder von Maria-Hilf (first practiced his trade in Ahrweiler)

- Wolfgang Müller von Königswinter (1816–1873), doctor, politician, poet and patriotic poet, died in Bad Neuenahr

- Franz von Chelius (1821–1899), ophthalmologist and surgeon (died in Ahrweiler)

- Hermann Cuno (1831–1896), architect of the Martin Luther Church in Bad Neuenahr, built in 1872

- Johannes Maria Assmann (1833–1903), Catholic clergyman and field provost (military bishop) of the Prussian army (died during a spa stay in Bad Neuenahr)

- Anton Fischer (Cardinal) (1840–1912), Archbishop of Cologne (1902–1912), died in Bad Neuenahr during the cure

- Armand Mieg (1834–1917), Bavarian officer and weapons designer (was accidentally shot by a fellow hunter on a hunting trip on March 10, 1917 and died the following day from his serious injuries in Ahrweiler)

- Peter Joerres (1837–1915), historian and local researcher, 1908 founder of the Ahrgau Museum (the former State New Language High School Ahrweiler was renamed the Peter-Joerres-Gymnasium in 1984)

- Carlos Otto (1838–1897), chemist and student of Justus von Liebig, pioneer of coal chemistry, co-founder of the Dr. C. Otto & Comp. (died in Ahrweiler)

- Josef Seché (1850–1901), architect of the station buildings in Ahrweiler and Bad Neuenahr (around 1880)

- Wilhelm Broekmann (1842–1916), lawyer, district judge in Ahrweiler and member of the German Reichstag (died in Bad Neuenahr)

- Blandine Merten ( Sister Blandine ) (1883-1918), religious sister and blessed (joined the Ursuline Congregation Calvarienberg in Ahrweiler in 1908; there is also a "Blandine Archive" and a "Blandine Museum")

- Ebba Tesdorpf (1851–1920), Hamburg-based draftsman and watercolorist (died during a spa stay in Ahrweiler)

- Paul Metternich (1853–1934), German diplomat (died in the Heppingen district)

- Joseph Mausbach (1861–1931), theologian and politician (center) (died in Ahrweiler)

- Max von Schillings (1868–1933), composer, conductor and theater director (scandal over the admission of the mother-in-law to the Dr. von Ehrenwall'sche Klinik. The lawyer Paul Elmer, who at the time advocated a reform of the German law on the insane, discussed the case in an educational pamphlet with the title "Money and Madhouse" (1914))

- Antonius Mönch (1870–1935), Roman Catholic Auxiliary Bishop in Trier ("Middle Reife" at the "Higher City School" in Ahrweiler)

- Nikolaus Irsch (1872–1956), theologian, philosopher and art historian (chaplain in Ahrweiler; 1907 to 1920 senior teacher at the Progymnasium, now Peter-Joerres-Gymnasium, in Ahrweiler; 1933 papal secret chamberlain)

- Christian Hülsmeyer (1881–1957), German entrepreneur, inventor, high-frequency technician (carried out first attempts at location with the help of radio waves in 1904 ; died in Ahrweiler)

- Kornelius Feyen (1886–1957), pedagogue, painter, conductor, pianist and singer (died during a spa stay)

- Jacob Jacobson (1888–1968), German-Jewish historian and expert on Jewish genealogy , archivist and Holocaust survivor , died in Bad Neuenahr.

- Christine Demmer (1893–1969), master hairdresser and opposition member against National Socialism (lived and died in Bad Neuenahr)

- Friederike Nadig (1897–1970), politician and one of the four “mothers of the Basic Law” (after the seizure of power she was banned from working as a health care worker in Ahrweiler in 1936)

- Georg Habighorst (1899–1958), doctor (medical councilor) in Ahrweiler and politician

- Werner Lindenbein (1902–1987), agricultural botanist and seed researcher (died in Ahrweiler)

- Georg Feydt (1907–1972), engineer, long-time head of the federal school of the technical relief organization in Marienthal and head of the federal school of disaster control in Ahrweiler

- Ida Noddack (1896–1978), German chemist, died in Bad Neuenahr

- Heinrich Böll , writer and Nobel laureate in literature, and family: In the years 1943–1944, the family found refuge from the chaos of Cologne in a hotel in Ahrweiler. Heinrich Böll was in the Neuenahr hospital in November 1944.

- Heinz Korbach (1921-2004), politician (from 1965 to 1973 District Administrator of the Ahrweiler district)

- Peter Gabrian (1922–2015), painter, graphic artist and sculptor (most recently lived and worked in Bad Neuenahr-Ahrweiler; portrayed Kurt Beck and Andrea Nahles )

- Johanna Pelizaeus (1824–1912), pedagogue, teacher and founder of the Pelizaeus grammar school in Paderborn (first job as a teacher in the boarding school of the "Ursulines on Calvarienberg")

- Hans Bernhard Graf von Schweinitz (1926-2008), ministerial official, politician and writer (lived and worked in Bad Neuenahr-Ahrweiler until his death)

- Günther Steines (1928–1982), athlete; Bronze medalist at the 1952 Summer Olympics in Helsinki with the 4 x 400 meter relay (most recently director of studies at today's Peter-Joerres-Gymnasium)

- Ignaz Görtz (1930–2018), local history researcher and archivist

- Ernst Alt (1935–2013), painter and sculptor (bronze portal of the St. Laurentius Church in Ahrweiler)

- Florian Mausbach (* 1944), urban planner, 1995–2009 President of the Federal Office for Building and Regional Planning (The partial preservation of the government bunker in Ahrweiler as a Cold War Museum goes back to his initiative.)

- Joachim Weiler (1947–1999), politician, district administrator of the Ahrweiler district until his death

- Walter Wirz (* 1947), politician, CDU member of the state parliament for the constituency of Bad Neuenahr-Ahrweiler

- Ulrich Schmücker (1951–1974), terrorist and undercover agent for the West Berlin Office for the Protection of the Constitution (grew up in Bad Neuenahr-Ahrweiler)

- Pen Cayetano (* 1954), musician and painter from Belize (moved to Germany in 1990 and has lived with his family in Ahrweiler since then)

- Rudolf Holze (* 1954), chemist and university professor for physical chemistry and electrochemistry (graduated from the Peter-Joerres-Gymnasium in 1973)

- Günter Ruch (1956–2010), author (lived and worked in Bad Neuenahr-Ahrweiler until his death from cancer)

- Stephan Maria Glöckner (* 1961), designer and musician (graduated from Are Gymnasium Bad Neuenahr-Ahrweiler in 1982)

- Anno Saul (* 1963), screenwriter and film director (graduated from Peter-Joerres-Gymnasium Ahrweiler in 1983)

- Bernhard Weber (* 1969), game designer, completed his Abitur in 1988 at Are Gymnasium Bad Neuenahr-Ahrweiler

- Sandra Minnert (* 1973), trainer of the women's soccer Bundesliga club SC 07 Bad Neuenahr

literature

- Alfred Oppenhoff: 1100 years of Ahrweiler - a journey through its eventful history. In: Heimatjahrbuch Kreis Ahrweiler, 1993, p. 86.

- Hans-Georg Klein: Ahrweiler. Gaasterland Verlag, Düsseldorf 2005, ISBN 3-935873-05-0 .

- Christian von Stramberg , Anton Joseph Weidenbach : Memorable and useful Rhenish antiquarius ... Part 3, Volume 9, pp. 615–799, Koblenz 1862.

Web links

|

Further content in the sister projects of Wikipedia:

|

||

|

|

Commons | - multimedia content |

|

|

Wiktionary | - Dictionary entries |

|

|

Wikisource | - Sources and full texts |

|

|

Wikinews | - News |

|

|

Wikivoyage | - Travel Guide |

- Web presence of the city of Bad Neuenahr-Ahrweiler

- Information on Bad Neuenahr-Ahrweiler from Ahrtal Tourism

- Information on the Bad Neuenahr spa is available from the Bad Neuenahr-Ahrweiler spa society

- Literature about Bad Neuenahr-Ahrweiler in the Rhineland-Palatinate state bibliography

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c State Statistical Office Rhineland-Palatinate - population status 2019, districts, municipalities, association communities ( help on this ).

- ↑ a b Main statutes of the city of Bad Neuenahr-Ahrweiler from August 3rd, 1999, last amended by statutes of January 6th, 2016. (PDF; 74 kB) (No longer available online.) In: bad-neuenahr-ahrweiler.de. City of Bad Neuenahr-Ahrweiler, January 6, 2016, archived from the original on December 10, 2016 ; accessed on December 12, 2016 .

- ↑ a b c d e f g State Statistical Office Rhineland-Palatinate: My village, my city. Retrieved January 9, 2020 .

- ↑ The location is now fixed. State Garden Show 2022. In: rlp.de. State Chancellery Rhineland-Palatinate , September 20, 2016, accessed October 1, 2016 .

- ↑ City of Bad Neuenahr-Ahrweiler, population statistics as of June 30, 2018

- ↑ Robert Bous and Hans-Georg Klein (eds.): Sources for the history of the city of Ahrweiler, vol. 1 . No. 108.Bad Neuenahr-Ahrweiler 1998, p. 65 .

- ↑ Germania Judaica II, 1 pp. 3-4; III, 1 pp. 5-7.

- ↑ Rheinischer Antiquarius, III. Abt., Vol. 9, p. 650 ff.

- ^ Hermann Keussen: Wilhelm, Archbishop of Cologne . In: Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie (ADB). Volume 43, Duncker & Humblot, Leipzig 1898, pp. 113-115.

- ↑ LhaKo Order 18 (Prüm Abbey) No. 96-99, 109, 138-141

- ↑ Rheinischer Antiquarius, III. Abt., Vol. 9, pp. 659 ff.

- ↑ Hans-Georg Klein: The siege of Ahrweiler 1474 . In: HJbKAhrweiler . 1999, p. 66-75 .

- ↑ Rheinischer Antiquarius, III. Abt., Vol. 9, pp. 690, 695 ff.

- ↑ Paul Krahforst: Ahrweiler witch trials in the 16th and 17th centuries , in: Heimatjahrbuch Kreis Ahrweiler, born 1977, p. 66.

- ↑ Rheinischer Antiquarius, III. Abt., Vol. 9, p. 710 f.

- ↑ Josef Müller: 1646 - a terrible year of the Thirty Years' War in Ahrweiler . In: HJbKAhrweiler . 1993, p. 95.

- ^ Wilhelm Fabricius : Explanations of the Historical Atlas of the Rhine Province, The Map of 1789 (2nd Volume), Bonn 1898. P. 56, 277, 283, 303, 537

- ↑ AJ Weidenbach: The thermal baths of Neuenahr ... a complete guide for spa guests. Bonn 1864 ( limited preview in Google book search - very detailed about the bathroom and its facilities in the middle of the 19th century).

- ↑ AW Wiki. Ahrweiler district , accessed on October 10, 2015 .

- ↑ Official municipality directory (= State Statistical Office of Rhineland-Palatinate [Hrsg.]: Statistical volumes . Volume 407 ). Bad Ems February 2016, p. 158 (PDF; 2.8 MB).

- ↑ 2011 Rhineland-Palatinate census ; pdf, accessed December 3, 2018

- ↑ Budget statute of the district town of Bad Neuenahr-Ahrweiler for the year 2019. (PDF) In: bad-neuenahr-ahrweiler.de. City of Bad Neuenahr-Ahrweiler, p. 5 , accessed on February 21, 2020 .

- ↑ https://www.bad-neuenahr-ahrweiler.de/politik/wahlen-und-abstektiven/europa-und-kommunalwahlen-2019/stadtrat-bad-neuenahr-ahrweiler/

- ^ The Regional Returning Officer Rhineland-Palatinate: Municipal elections 2014, city and municipal council elections

- ^ Rhein-Zeitung: After election in November: Orthen appointed mayor for the second time. December 18, 2017, accessed December 17, 2019 .

- ↑ City arms. City administration Bad Neuenahr-Ahrweiler, accessed on January 20, 2016 .

- ↑ Querying the course book route 477 at Deutsche Bahn.

- ^ Association meeting, 55th meeting. (PDF; 8.52 MB) (No longer available online.) In: TOP 3. SPNV Nord , p. 6 , formerly in the original ; Retrieved September 26, 2016 . ( Page no longer available , search in web archives )

- ↑ Ahr Valley Express Bad Neuenahr-Ahrweiler. Altstadtexpress Koblenz, accessed on August 19, 2015 .

- ↑ The tower on the Neuenahr mountain on lokalkompass.de

- ^ Rudolf Leisen, Günter Köster: History of the parish of St. Barbara . Ramersbach 2008, ISBN 978-3-930376-57-5 .

- ^ The "Stolpersteine" project in Bad Neuenahr-Ahrweiler ( Memento from February 28, 2014 in the Internet Archive )

- ^ Heinrich Gemkow : Karl Marx 'last stay in Germany. As a spa guest in Bad Neuenahr in 1877 . Plambeck, Neuss 1986 ISBN 3-88501-063-1 .

- ↑ Short biography of Conrad Albert Ursprung on the website of the Barmen district ( memento from March 9, 2016 in the Internet Archive ); Dietrich Kämper : Conrad Albert Ursprung jr. , in: Karl Gustav Fellerer (Ed.): Rhenish musicians. 5th episode . A. Volk, Cologne 1967, pp. 129-130

- ^ Obituary for the death of Georg Feydt . ZS-Magazin - magazine for civil protection, disaster control and self-protection, May 1972 edition. Accessed on March 7, 2014. (PDF)

- ↑ Letters from the war 1939–1945 from Heinrich Böll . Heinrich Böll Foundation, accessed on October 12, 2019